CHAPTER NINE

THERE IS GOOD MONEY AND

THERE IS BAD MONEY

Does it matter whose money funds the business I want to grow? How might the expectations of the suppliers of my capital constrain the decisions I’ll be able to make? Is there something about venture capital that does a better job nurturing disruptive businesses than corporate capital? What can corporate executives do to ensure that the expectations that accompany their funding will cause managers to correctly make the decisions that will lead to success?

Getting funded is an obsession for most innovators with a great idea; as a result, most research about raising capital has focused on how to get it. For corporate entrepreneurs, writers often describe the capital budgeting process as a cumbersome bureaucracy and recommend that innovators find a well-placed “champion” in the hierarchy who can work the system of numbers and politics in order to get funding. For start-ups seeking venture capital, much advice is focused on structuring deals that do not give away too much control, while still allowing them to benefit from the networks and acumen that venture capital firms offer.1

Although this advice is useful, it skirts an issue that we think is potentially more important: The type of money that corporate executives provide to new-growth businesses and the type of capital that managers of those businesses accept represent fundamental early choices when launching a new-growth business. These are critical fork-in-the-road decisions, because the type and amount of money that managers accept define the investor expectations that they’ll have to meet. Those expectations then heavily influence the types of markets and channels that the venture can and cannot target. Because the process of securing funding forces many potentially disruptive ideas to get shaped instead as sustaining innovations that target large and obvious markets, the very process of getting the money to start a venture actually sends many of them on a march toward failure.

We have concluded that the best money during the nascent years of a business is patient for growth but impatient for profit. Our purpose in this chapter is to help corporate executives understand why this type of money tends to facilitate success, and to see how the other category of capital—which is impatient for growth but patient for profit—is likely to condemn innovators to a death march if it is invested at early stages. We also hope this chapter will help those who bankroll new businesses understand the forces that make their money good or bad for nurturing growth.

The most commonly used theories about good and bad money for new-growth ventures have been based on attributes rather than circumstances. Probably the most common attribute-based categorization is venture capital versus corporate capital. Other categories include public versus private capital, and friends and family versus professionally managed money. None of these categorization schemes supports a theory that can reliably predict whose money will best help new ventures to succeed. Sometimes money from each of these categories proves to be a boon, and sometimes it becomes the kiss of death.

We’ve already demonstrated why the money that funds a new-growth business needs to be patient for growth. Competing against nonconsumption and moving disruptively up-market are critical elements of a successful new-growth strategy—and yet by definition, these disruptive markets are going to be small for a time. The only way that a venture can instantly become big is for existing users of a high-volume product to be enticed to switch en masse to the new enterprise’s product. This is the province of sustaining innovation, and start-ups rarely can win a sustaining-innovation battle. Money should be impatient for growth in later-stage, deliberate-strategy circumstances, after a winning strategy for the new business has emerged.

Money needs to be impatient for profit to accelerate a disruptive venture’s initial emergent strategy process. When new ventures are expected to generate profit relatively quickly, management is forced to test as quickly as possible the assumption that customers will be happy to pay a profitable price for the product—that is, to see whether real products create enough real value for which customers will pay real money. If a venture’s management can keep returning to the corporate treasury to fund continuing losses, managers can postpone this critical test and pursue the wrong strategy for a long time. Expectations of early profit also help a venture’s managers to keep fixed costs low. A business model that can make money at low costs per unit is a crucial strategic asset in both new-market and low-end disruptive strategies, because the cost structure determines the type of customers that are and are not attractive. The lower it can start, the greater its upside. And finally, early profitability protects a growth venture from cutbacks when the corporate bottom line turns sour.2

In the following sections we describe in more detail how good money becomes bad. We recount this process from the point of view of corporate investors, with the hope that this telling of the story will help managers who are seeking funding to know good and bad money when they see it, and to understand the consequences of accepting each type. We hope also that venture capital investors and the entrepreneurs whom they fund will be able to see in these accounts parallel implications for their own operations. Bad money can come from venture and corporate investors—as can good money.

The Death Spiral from Inadequate Growth

Good money turns bad in a self-reinforcing downward spiral that makes it very difficult for even the best executives to do anything except preside over the company’s demise. There are five steps in this spiral. Once a company has fallen into it, it becomes almost impossible not to take the subsequent steps.

Step 1: Companies Succeed

After using an emergent strategy process to find a successful formula, a young company hits its stride with a product that helps customers get an important job done better than any competitor. With the winning strategy now clear, the executive team wrestles control of the strategy-making process away from emergent influences and deliberately focuses all investments to exploit this opportunity.3 Anything that would divert resources from the crucial, deliberate focus on growing the core business is stomped out. Such focus is an essential requirement for success at this stage.4 However, it means that no new-growth businesses are launched while the core business is still thriving.

This focus propels the company up its sustaining trajectory ahead of competitors who are less aggressive and less focused. Because margins at the high end are attractive, the company barely notices when it begins losing low-end, price-sensitive business in what comes to be viewed as a “commodity segment.” Exiting the lowest-margin products and replacing those revenues with higher-margin products at the top of the sustaining trajectory typically feels good, because overall gross profit margins improve.

Step 2: Companies Face a Growth Gap

Despite the company’s success, its executives soon realize that they are facing a growth gap. This is caused by the pesky tendency of Wall Street investors to incorporate expected growth into the present value of a stock—so that meeting growth expectations results only in a market-average rate of stock price appreciation. The only way that managers can cause their companies’ share prices to increase at a faster rate than the market average is to exceed the growth rate that investors have already built into the current price level. Hence, managers who seek to create shareholder value always face a growth gap—the difference between how fast they are expected to grow and how much faster they need to grow to achieve above-average returns for shareholders.5

As a rule, executives meet investor expectations through sustaining innovations. Investors understand the businesses in which companies presently compete and the growth potential that lies along the sustaining trajectory in those businesses—which they discount into the present value of the stock price. Sustaining innovation is therefore critical to maintaining a company’s share price.6

It is the creation of new disruptive businesses that allows companies to exceed investor expectations, and therefore to create unusual shareholder value. For precisely the reasons why established companies are prone to underestimate the growth potential in disruptive businesses, investors likewise have consistently underestimated (and therefore have been pleasantly surprised by) the growth potential of disruptions. Creating new disruptive businesses is the only way in the long term to continue creating shareholder value.

When a company’s revenues are denominated in millions of dollars, the amount of new business that managers need in order to close the growth gap—new revenues and profits from unknown and yet-tobe-discounted sources—also is denominated in the millions of dollars. But as a company’s revenues grow into the billions, the size threshold of new business that is required to sustain its growth rate, let alone exceed investors’ expectations, gets bigger and bigger and bigger. At some point the company will report slower growth than investors had discounted, and its stock price will take a hit as investors realize that they had overestimated the company’s growth prospects.

To get the stock price moving again, senior management announces a targeted growth rate that is significantly higher than the realistic underlying growth rate of the core businesses. This creates a growth gap even larger than the company has ever faced before—a gap that must be filled by new-growth products and businesses that the company has yet to conceive. Announcing an unrealistic growth rate is the only viable course of action. Executives who refuse to play this game will be replaced by managers who are willing to try. And companies that do not attempt to grow will see their market capitalization decline until they get acquired by companies that are eager to play.

Step 3: Good Money Becomes Impatient for Growth

When confronted with a large growth gap, the corporation’s values, or the criteria that are used to approve projects in the resource allocation process, will change. Anything that cannot promise to close the growth gap by becoming very big very fast cannot get through the resource allocation gate in the strategy process. This is where the process of creating new-growth businesses comes off the rails. When the corporation’s investment capital becomes impatient for growth, good money becomes bad money because it triggers a subsequent cascade of inevitable incorrect decisions.

Innovators who seek funding for the disruptive innovations that could ultimately fuel the company’s growth with a high probability of success now find that their trial balloons get shot down because they can’t get big enough fast enough. Managers of most disruptive businesses can’t credibly project that the business will become very big very fast, because new-market disruptions need to compete against nonconsumption and must follow an emergent strategy process. Compelling them to project big numbers forces them to declare a strategy that confidently crams the innovation into a large, existing, and obvious market whose size can be statistically substantiated. This means competing against consumption.

After senior executives have approved funding for this inflated growth project, the company’s managers cannot then back down and follow an emergent strategy that seeks to compete against nonconsumption. They are on the hook to deliver the growth that they projected. They therefore must ramp expenses according to plan.

Step 4: Executives Temporarily Tolerate Losses

It becomes clear that competing against consumption in a large and obvious market will be an expensive challenge, because if customers are to buy the product, it must perform better than the products that customers already are using. The team warns senior executives that stomaching huge losses is a prerequisite to winning the pot of gold. Determined to be visionary with the long-term interests of the company in mind, executives therefore accept the reality that the business will lose significant money for some time. There is no retreat. Executives convince themselves that investing for growth will result in growth, as if there were a linear relationship between the two—as if the more aggressively you invest to build the new business, the faster it will take off.7

In order to meet the budgeted timetable for rollout and ramp-up, the project managers put the cost structure in place before there are revenues—and because they must support a steep revenue ramp, these costs are substantial. But overfunding is hazardous to a new venture’s health, because heavy expense levels in turn define the sorts of customers and market segments that will and will not provide adequate revenues to cover those costs. If this happens, then customers who come from nonconsumption in emerging applications and are therefore delighted with simple products—in short, the ideal customers for a disruptive venture—inevitably become unattractive to the business. The ideal channels—those that need something to fuel their own disruptive march up-market against their competition—also become unattractive. Only the largest channels that reach the largest populations appear to be capable of bringing in enough revenue fast enough.

This completes the character transformation of the corporation’s money. It has become bad money for new-market disruption: Impatient for growth but patient for profit.

Step 5: Mounting Losses Precipitate Retrenchment

As the venture’s managers try to succeed by competing against consumption, they find all sorts of reasons why customers prefer to continue buying the products they have always used from the vendors they have always trusted. Often these reasons entail the kinds of interdependencies we discussed in chapter 5. Breakthrough sustaining innovations can rarely be hot-swapped into existing systems of use. Typically, many other unanticipated things need to change in order for customers to be able to benefit from using the new product. While revenues fall far short, expenses are on budget. Losses mount. The stock price then gets hammered again, as investors realize anew that their expectations for growth cannot be met.

A new management team gets brought in to rescue the stock price. To stanch the bleeding, the new team stops all spending except what is required to keep the core business strong. Refocusing on the core is welcome news. It is a tried-and-true formula for performance improvement, because the company’s resources, processes, and values have been honed exactly for this task. The stock price bounces in response, but as soon as the new price has fully discounted whatever growth potential exists in the core business, the new executives realize that they must invest to grow. But now the company faces an even greater growth gap, and the situation loops back to step 3, where the company needs new-growth businesses that can get really big really fast. That pressure then causes management to repeat the tragic sequence of wrong decisions again and again, until so much value has been destroyed that the company is acquired by another corporation, which itself had been unable to generate its own growth through disruption but saw in the acquisition a synergistic opportunity to wring cost out of the combination.

How to Manage the Dilemma of Investing for Growth

The dilemma of investing for growth is that the character of a firm’s money is good for growth only when the firm is growing healthily. Core businesses that are still growing provide cover for new-growth businesses. Senior executives who are bolstered by a sense that the pipeline of new sustaining innovations in established businesses will meet or exceed investors’ expectations can allow new businesses the time to follow emergent strategy processes while they compete against nonconsumption. It is when growth slows—when senior executives see that the sustaining-innovation pipeline is inadequate to meet investor expectations—that investing to grow becomes hard. The character of the firm’s money changes when new things must get very big very fast, and it won’t allow innovators to do what is needed to grow. When you’re a corporate entrepreneur and you sense this shift in the corporate context occurring, you had better watch out.

This dilemma traps nearly every company and is the causal mechanism behind the findings in Stall Points, the Corporate Strategy Board’s study that we cited in chapter 1.8 This study showed that of the 172 companies that had spent time on Fortune’s list of the 50 largest companies between 1955 and 1995, 95 percent saw their growth stall to rates at or below the rate of GNP growth. Of the companies whose growth stalled, only 4 percent were able to successfully reignite their growth even to a rate of 1 percent above GNP growth. Once growth had stalled, the corporations’ money turned impatient for growth, which rendered it impossible to do the things required to launch successful growth businesses.

In recent years, the dilemma has become even more complex. If companies whose growth has stalled somehow find a way to launch a successful new-growth business, Wall Street analysts often complain that they cannot value the new opportunity appropriately because it is buried within a larger, slower-growing corporation. In the name of shareholder value, they demand that the corporation spin off the new-growth business to shareholders so that the full value of its exciting growth potential can be reflected in its own share price. If executives respond and spin it off, they may indeed “unlock” shareholder value. But after it has been unlocked they are left locked again in a low-growth business, facing the mandate to increase shareholder value.

In the face of this sobering evidence, chief executives—whose task it is to create shareholder value—must preserve the ability of their capital to nourish growth businesses in the ways that they need to be nourished. When executives allow the growth of core businesses to sag to lackluster levels, new-growth ventures must shoulder the whole burden of changing the growth rate of the entire corporation’s top and bottom lines. This forces the corporation to demand that the new businesses become very big very fast. Their capital as a consequence becomes poison for growth ventures. The only way to keep investment capital from spoiling is to use it when it is still good—to invest it from a context that is still healthy enough that the money can be patient for growth.

In many ways, companies whose shares are publicly held are in a self-reinforcing vise. Their dominant shareholders are pension funds. Corporations pressure the managers of their pension fund investments to deliver strong and consistent returns—because strong investment performance reduces the amount of profits that must be diverted to fund pension obligations. Investment managers therefore turn around and pressure the corporations whose shares they own to deliver consistent earnings growth that is unexpectedly accelerating. Privately held companies are not subject to many of these pressures. The expectations that accompany their capital therefore can often be more appropriate for the building of new-growth businesses.

Use Pattern Recognition, Not Financial Results,

to Signal Potential Stall Points

Because outsiders typically measure a company’s success by its financial results, executives are tempted to rely on changes in financial results as signals that they should take comfort or take action. This is folly, however, because the financial outcomes of the most recent period actually reflect the results of investments that were made years earlier to improve processes and to create new products and businesses. Financial results measure how healthy the business was, not how healthy the business is.9 Financial results are a particularly bad tool to manage disruption, because moving up-market feels good financially, as we have noted previously.

Executives should gingerly use data of any sort when looking into the future, because reliable data are typically available only about the past and will be an accurate guide only if the future resembles the past.10 To illustrate the limitations of data in disruptive decision making, let us recount an experience that Clayton Christensen had in a recent MBA class. He had written a paper that worried that the leading business schools’ traditional two-year MBA programs are being threatened by two disruptions. The most proximate wave, a low-end disruption, is executive evening-and-weekend MBA programs that enable working managers to earn MBA degrees in as little as a year. The most significant wave is a new-market disruption: on-the-job management training that ranges from corporate educational institutions such as Motorola University and GE’s Crotonville to training seminars in Holiday Inns.

Christensen asked for a student vote at the beginning of class: “After reading the paper, how many of you think that the leading MBA programs are being disrupted?” Three of the 102 students raised their hands. The other 99 took the position that these developments weren’t relevant to the venerable institutions’ fortunes.

Christensen then asked one of the three who was worried to explain why. “There’s a real pattern here,” he responded, and he listed six elements of the pattern. These included MBA salaries overshooting what operating companies can afford; the disruptors competing against nonconsumption; people hiring on-the-job education to get a very different job done; a shift in the basis of competition to speed, convenience, and customization; and interdependent versus modular curricula. He concluded that the pattern fit: All of the things that had happened to other companies as they were disrupted were indeed under way in management education. “That’s why I’d take this seriously,” he concluded.

Christensen then turned to those who weren’t concerned, and asked why. They tended to point to the data—the numbers of students still battling to be admitted into the leading schools, the attractive starting salaries of the graduates, the brand reputations of the programs, loyal alumni and great on-campus networking opportunities, and so on. None of the disruptive programs could come even close to competing on these dimensions.

Christensen then asked one of the most vocal defenders of the invincibility of the leading business schools, “What if you were dean of one of these schools. What data would convince you that this was something that you needed to address?”

“I’d look at the school’s market share among the CEOs of the Global 1000 corporations,” he responded. “If our market share started to drop, then I’d worry.” Christensen then asked whether that data would be a signal that he should begin addressing the problem or that the game was over. “Oh, I guess the game would be over by then,” he admitted.

“Anybody else?” Christensen pressed. “Imagine that you were dean. What data would convince you that you should take action?” Several proposed evidence that they would find convincing, but in every case, the class concluded that by the time convincing data became available, the game would be over for the high-quality two-year MBA programs.

When Christensen asked, “Should these schools view this as a threat or an opportunity?” there was another interesting reaction. There was little energy in the class regarding the growth opportunity that on-the-job management education presented for the leading business schools. We suspect that the reason for the students’ indifference is related to the threat-versus-opportunity paradox highlighted in chapter 3. At the time of this writing, the leading business schools are at the top of their game, by any measure of financial, academic, and competitive performance. They don’t need growth to feel healthy. There is nothing yet in the measures of strength and organizational vitality to suggest that the world these programs have enjoyed is likely to change.11

Create Policies to Invest Good Money Before It Goes Bad

When you’re driving a car, you can wait until the fuel gauge drops toward empty before you refill the tank, and once the tank is full again you can rev the car back up to full speed. It just isn’t possible to manage growth in the same way—to wait until the growth gauge begins falling toward zero before you seek a fill-up from new-growth businesses. The growth engine is a much more delicate machine that must be kept running continuously by process and policy, rather than by reacting when the growth gauge reads empty. We suggest three particular policies for keeping the growth engine running. Taken together, the policies force the organization to start early, start small, and demand early success.

- Launch new-growth businesses regularly when the core is still healthy—when it can still be patient for growth—not when financial results signal the need.

- Keep dividing business units so that as the corporation becomes increasingly large, decisions to launch growth ventures continue to be made within organizational units that can be patient for growth because they are small enough to benefit from investing in small opportunities.

- Minimize the use of profit from established businesses to subsidize losses in new-growth businesses. Be impatient for profit: There is nothing like profitability to ensure that a high-potential business can continue to garner the funding it needs, even when the corporation’s core businesses turn sour.

Start Early: Launch New-Growth Businesses Regularly While the Core Is Still Healthy

Establishing a policy that mandates the launch of new disruptive growth businesses in a predetermined rhythm is the only way that executives actually can avoid reacting after the growth engine has stalled. They must regularly launch or acquire new-growth businesses while their core businesses are still growing healthily, because when growth slows, the dramatic change in the company’s values that ensues makes growth impossible. If executives do this, and continue to shape the strategies of those businesses to be disruptive, soon a new business or two will punch into the realm of major revenue every year, ready to sustain the total corporation’s growth. If executives use their corporations’ investment capital when they can be patient for growth, the money will not spoil. It remains fresh, able to fund new-growth businesses.

Acquire New-Growth Businesses in a Predetermined Rhythm

Some executives of large, successful companies fear that even if they develop high-potential ideas and business plans for disruptive growth businesses, they just won’t be able to create the processes and values required to nurture them. They therefore are inclined to buy disruptive growth businesses, rather than to make them internally. Acquisition can be a very successful strategy if it is guided by good theory.

Many corporate acquisitions are triggered by the arrival of an investment banker with a business to sell. Decisions to acquire or not are often driven by discounted cash flow projections and an assessment of whether the business is undervalued or fixable or can yield cost savings through synergies with an existing business. Some of the theories that are used to justify these acquisitions prove to be accurate, and the acquisitions create great value. But most of them don’t.12

Corporate business development teams can just as readily acquire disruptive businesses. If they wait until the growth trajectories of these companies are obvious to everyone, of course, the disruptive companies may be too expensive to acquire. But if a business development team identifies candidates through the lenses of the theories in chapters 2 through 6 rather than waiting for conclusive historical evidence, then acquiring early-stage disruptive growth businesses in a regular rhythm can be a great strategy for creating and sustaining a corporation’s growth. In contrast to the acquisition of mature businesses that put a company on a higher but still flat revenue trajectory, acquiring early-stage disruptive companies can change the slope of the revenue trajectory.

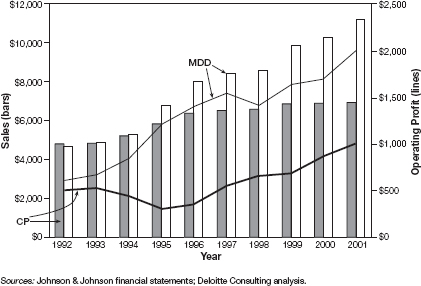

One company whose fortunes have been heavily shaped by acquiring disruptive businesses has been Johnson & Johnson. For most of the 1990s, J&J was organized in three major operating groups—ethical pharmaceuticals, medical devices and diagnostics (MDD), and consumer products. Figure 9-1 shows that in 1993 the consumer and MDD groups were comparably sized, each generating just under $5 billion in sales. They subsequently grew at very different rates. The consumer business’s intrinsic growth trajectory was essentially flat, and it grew by acquiring big new revenue platforms, such as Neutrogena and Aveeno, whose growth trajectories were similarly flat. Although these acquisitions put the revenue line of the consumer group on a higher platform, they did not change the slope of the platform—and remember that it is changes in the slope of the platform, not the level of the platform, that create shareholder value at an above-average rate. Even with the acquisitions, the consumer group’s total revenues only grew at about a 4 percent annual rate over the decade.

In contrast, the MDD group of businesses grew at over 11 percent annually over the same period. This was driven by four disruptive businesses, each of which the company had acquired. J&J’s Ethicon Endo-Surgery company makes instruments for endoscopic surgery, a disruption relative to conventional invasive surgery. Its Cordis division makes instruments for angioplasty, which is disruptive relative to open-heart cardiac bypass surgery. The company’s Lifescan division makes portable blood glucose meters that enable patients with diabetes to test their own blood sugar levels instead of needing to go to hospital laboratories. And J&J’s Vistakon disposable contact lenses were disruptive relative to traditional lenses made by companies such as Bausch & Lomb. The strategies of each of these businesses fit precisely the litmus tests for new-market disruption described in chapter 2. Together, they have grown at a 43 percent annual rate since 1993, and now account for about $10 billion in revenue. The group’s overall growth rate was 11 percent because the other MDD group companies—those not on disruptive trajectories—grew in aggregate at a 3 percent annual rate. Both the consumer and MDD groups grew through acquisition. The growth rates of the two groups differed because MDD acquired businesses with disruptive potential, whereas the consumer group acquired premium businesses that were not disruptive.13

FIGURE 9 - 1

Johnson & Johnson Consumer Products (CP) Versus Medical Devices & Diagnostics (MDD) Revenue and Operating Profit, 1992–2001

Hewlett-Packard also sustained its growth for nearly two decades after its core lines of business matured, using a hybrid strategy for finding disruptions. Its acquisition of Apollo Computer, a leading workstation maker, was the platform upon which HP built its microprocessor-based computer businesses, which disrupted minicomputer makers such as Digital Equipment. HP’s ink-jet printer business, which today provides a significant portion of the corporation’s total profit, was a disruption that was conceived and launched internally, but within an organizationally autonomous business unit.

GE Capital, which was the primary engine of value creation for GE shareholders in the 1990s, has been a massive disruptor in the financial services industry. It has grown through a hybrid strategy of incubating disruptive businesses in some segments of the industry and acquiring others.

Start Small: Divide Business Units to Maintain Patience for Growth

The second policy imperative is to keep operating units relatively small. A decentralized company can maintain the values required to see and enthusiastically pursue disruptive innovations far longer than can a monolithic, centralized one, because the size that a new disruptive venture must reach to make a difference to a small business unit is more consistent with the revenue ramp of a new disruptive business.

Compare the perspective in a monolithic $20 billion company that needs to grow 15 percent annually with the perspective in a $20 billion corporation that is composed of twenty business units. The managers of the monolithic company will have to look at every proposed innovation from the perspective of needing to find $3 billion in new revenues beyond what was done in the prior year. The average perspective of the twenty business unit managers in the decentralized company, in contrast, is that they need to bring in $150 million of new business in the next year. In the multiple-business-unit firm there are more managers seeking disruptive growth opportunities, and more opportunities will look attractive to them.

In fact, most of the companies that appear to have transformed themselves over the past thirty years or so—companies such as Hewlett-Packard, Johnson & Johnson, and General Electric, for example—have been composed of a large number of smaller, relatively autonomous business units. These corporations have not transformed themselves by transforming the business models of their existing business units into disruptive growth businesses. The transformation was achieved by creating new disruptive business units and by shutting down or selling off mature ones that had reached the feasible end of their sustaining-technology trajectories.14

One reason the mortality rate of independent disk drive companies measured in The Innovator’s Dilemma was so high was that they all were single-business companies. As monolithic organizations—even relatively small ones—they had never learned how to manage nascent disruptive growth businesses alongside larger, maturing businesses. There were no processes for doing this.

In following the policy we are recommending, managers again need to be guided by theory, not by the numbers. Accountants will argue that redundant overhead expenses can be eliminated when business units are consolidated into much larger entities. Such analysts rarely assess the impact that consolidation has on the consequent demands in those mega-units that any new businesses that are launched must get very big very fast.15

Demand Early Success: Minimize Subsidization of New-Growth Ventures

The third policy, which is to expect new-growth businesses to generate profit relatively quickly, does two important things. First, it helps accelerate the emergent strategy process by forcing the venture to test as quickly as possible the assumption that there are customers who will pay attractive prices for the firm’s products. The fledgling business can then press on or change course based on this feedback. Second, forcing a venture to become profitable as soon as feasible helps protect it from being shut down when the core business turns sour.16

Honda: An Example of Forced Floundering

Not having much money proved to be a great blessing for Honda, for example, as it attacked the U.S. motorcycle market.17 Founded in postwar Japan by motorcycle racing enthusiast Suchiro Honda, by the mid-1950s the company had become best known for its 50cc Super Cub, designed as a more powerful but easy-to-handle moped that could wind its way through crowded Japanese streets for use as a delivery vehicle.

When Honda targeted the U.S. motorcycle market in 1958, its management set a seat-of-the-pants sales target of 6,000 units a year, representing 1 percent of the U.S. market. Securing support for the U.S. venture was not merely a matter of convincing Mr. Honda. The Japanese Ministry of Finance also had to approve the release of the foreign currency needed to set up operations in America. Hard on the heels of Toyota’s failed introduction of the Toyopet car, the Ministry was loathe to give up scarce foreign exchange. Only $250,000 was released, of which only $110,000 was cash; the rest had to be in inventory.

Honda launched its U.S. operations with inventory in each of its 50cc, 125cc, 250cc, and 305cc models. The biggest bets were placed on the largest motorcycles, however, because the U.S. market was composed exclusively of large bikes. In our parlance, Honda set out to achieve a low-end disruption, hoping to pick off the most price-sensitive customers in the existing market with a low-price, full-sized motorcycle.

In 1960 Honda sold a few models of its larger machines, which promptly began to leak oil and blow their clutches. It turned out that Honda’s best engineers, whose skills had been honed through developing products that performed well in short stop-and-go bursts in congested streets, didn’t know what they didn’t know about the demands of the constant, high-speed, over-the-road travel that was common among motorcyclists in the United States. Honda had little choice but to invest its precious currency in sending the defective bikes via air freight back to Japan. The problem almost broke Honda.

With almost all of its resources devoted to supporting and promoting the problematic larger machines against well-financed and successful incumbents, the Honda personnel in the United States turned to using the 50cc Super Cubs as their own transportation. They were reliable, cheap to run, and Honda figured they couldn’t sell them anyway: There simply was no market for motorbikes that small. Right?

The exposure the Super Cub got from the daily use of the Honda management team in Los Angeles generated surprising interest from individuals and retailers—not motorcycle distributors, but sporting goods shops. Running low on cash thanks to the difficulties encountered in selling the big bikes, Honda decided to sell the Super Cubs just to stay afloat.

Little by little, continued success in selling the Super Cub and continued disappointment with the larger machines eventually redirected Honda’s efforts toward the creation of an entirely new market segment—off-road motorbikes. Priced at one-fourth the cost of a big Harley, these were sold to people without leather jackets who never would have purchased deep-throated cycles from the established U.S. or European makers. They were used for fun, not over-the-road transportation. Apparently a low-end disruption wasn’t a viable strategy because there just weren’t enough over-the-road bikers who were over-served by the brands and muscle of Harleys, Triumphs, and BMWs. What emerged was a new-market disruption, which Honda subsequently did a masterful job of deliberately exploiting.

What pushed Honda to discover this market was its lack of financial resources. This prevented its managers from tolerating significant losses and instead created an environment in which the venture’s managers had to respond to unanticipated successes. This is the essence of managing the emergent strategy process.18

It is important to remember that this policy—to limit expenses and seek early profit in order to accelerate the emergent strategy process—is not a one-size-fits-all mandate. In circumstances in which a viable strategy needs to emerge—such as new-market disruptions—this is a helpful policy. In low-end disruptions, the right strategy often is much clearer much earlier. As soon as the market applications become clear, and a business model that can viably and profitably address that market has emerged, aggressive investment—impatience for growth—is appropriate.

Insurance for When the Corporation Refocuses on the Core

Another reason why turning an early profit is important to a new business’s success is that funding for new ventures very often gets cut off not because the ventures are off-plan, but because the core business is sick and needs all of the corporation’s resources to recover. When the downturn occurs, new-growth ventures that cannot play a significant and immediate role in the corporation’s return to financial health simply get sacrificed, even though everybody involved knows that they are cutting off the road to the future in order to salvage the present. The need to survive trumps the need to grow.19

Dr. Nick Fiore, who periodically speaks to our students at the Harvard Business School, is a battle-scarred corporate innovator whose experiences illustrate these principles in action. Fiore was hired at different points in his career by the CEOs of two publicly traded companies to start new-growth businesses that would set their corporations on robust growth trajectories.20 In both instances, the CEOs—powerful, reputable executives who were secure in their positions—had truthfully assured Fiore that the initiative to create new-growth businesses had the full and patient backing of the companies’ respective boards of directors.

Fiore cautions our students that if they ever receive such assurances, even from the most powerful and deep-pocketed executives in their companies, they had better watch out.

When you start a new growth business, there is a ticking clock behind you. The problem is that this clock ticks at a variable rate that is determined by the health of the corporate bottom line, not by whether your little venture is on plan. When the bottom line is healthy, this clock ticks patiently on. But if the bottom line gets troubled, the clock starts to tick real fast. When it suddenly strikes twelve, your new business had better be profitable enough that the corporate bottom line would look worse without you. You need to be part of the solution to the corporation’s immediate profit problems, or the guillotine blade will fall. This will happen because the board and the chairman have no option but to refocus on the core—despite what they may have told you with the best and most honest of intentions.21

This is why being impatient for profit is a virtuous characteristic of corporate capital. It forces new-growth ventures to ferret out the most promising disruptive opportunities quickly, and creates some (always imperfect) insurance against the venture’s getting zeroed out when the health of the larger organization becomes imperiled.

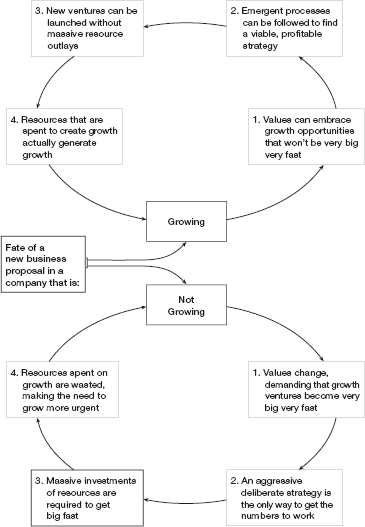

Figure 9-2 summarizes the virtues of policy-driven growth. It shows that appropriate policies, if well understood and appropriately implemented, can generate an upward spiral to replace the death spiral from inadequate growth that we described at the beginning of this chapter. When this happens, companies place themselves in a circumstance of continual growth. They invest their good money and avoid letting it go bad. This is the only way to avoid letting the growth engine stall and to sidestep the death spiral from inadequate growth.

FIGURE 9 - 2

Self-Reinforcing Spirals from Adequate and Inadequate Growth

Good Venture Capital Can Turn Bad, Too

Those working to build disruptive growth businesses within established corporations sometimes look longingly at the green grass on the other side of the corporate fence, where innovators who build independent start-ups not only can avoid the encumbrances of corporate bureaucracy but also have the freedom to fund their ideas with venture capital. The belief that venture capitalists can fund start-ups much more effectively than corporate capitalists is so pervasive, in fact, that the venture capital investment arms of many corporations refuse to participate in a deal unless an independent venture capital firm will co-invest.

We would argue, however, that the corporate-versus-venture distinction isn’t nearly as important as the willingness or inability to be patient for growth. Just like Honda, most successful venture capital firms had precious little capital to invest at the outset. The lack of money conferred on their ventures a superior capability in the emergent strategy process. When venture capitalists become burdened with lots of money, however, many of them seem to behave as corporate capitalists do in stages 3, 4, and 5 of the growth-gap spiral.

In the late 1990s venture investors plowed huge sums of capital into very early-stage companies, conferring extraordinary valuations upon them. Why would people with so much experience have done something so foolish as to invest all of that money in companies before they had products and customers? The answer is that they had to make investments of this size. Their small, early-stage investments had been so successful in the past that investors had shoveled massive amounts of capital into their new funds, expecting that they would be able to earn comparable rates of return on much larger amounts of money. The venture firms had not increased their number of partners in proportion to the increase in the assets that they were committed to invest. As a consequence, the partners simply could not be bothered with making little $2 million to $5 million early-stage investments of the very sort that had led to their initial success. Their values had changed. They had to demand that the ventures they invested in must become very big, very fast, just like their corporate counterparts.22

And just like their corporate counterparts, these funds then went through steps 3, 4, and 5 that were described at the beginning of this chapter. These venture funds weren’t victims of the bubble—the collapse in valuations that occurred between 2000 and 2002. In many ways they were the cause of it. They had moved up-market into the magnitudes of investment that normally are meted out in later deliberate strategy stages, but the early-stage companies in which they continued to invest were in a circumstance that needed a different type of capital and a different process of strategy.23 The paucity of early-stage capital that continues to prevent many entrepreneurs with great disruptive growth ideas from getting funding as of the writing of this book is in many ways the result of so many venture capital funds being in their equivalent of step 5 of the death spiral—retrenching and focusing all of their money and attention to fix prior businesses.

We often have been asked whether it is a good idea or bad idea for corporations to set up corporate venture capital groups to fund the creation of new growth businesses. We answer that this is the wrong question: They have their categories wrong. Few corporate venture funds have been successful or long-lived; but the reason is not that they are “corporate” or that they are “venture.” When these funds fail to foster successful growth businesses, it is most often because they invested in sustaining rather than disruptive innovations or in modular solutions when interdependence was required. And very often, the investments fail because the corporate context from which the capital came was impatient for growth and perversely patient for profitability.

The experience and wisdom of the men and women who invest in and then oversee the building of a growth business are always important, in every situation. Beyond that, however, the context from which the capital is invested has a powerful influence on whether the start-up capital that they provide is good or bad for growth. Whether they are corporate capitalists or venture capitalists, when their investing context shifts to one that demands that their ventures become very big very fast, the probability that the venture can succeed falls markedly. And when capitalists of either sort follow sound theory—whether consciously or by intuition or happenstance—they are much more likely to succeed.

The central message of this chapter for those who invest and receive investment can be summed up in a single aphorism: Be patient for growth, not for profit. Because of the perverse dynamics of the death spiral from inadequate growth, achieving growth requires an almost Zen-like ability to pursue growth when it is not necessary. The key to finding disruptive footholds is to connect with a job in what initially will be small, nonobvious market segments—ideally, market segments characterized by nonconsumption.

Pressure for early profit keeps investors willing to invest the cash needed to fuel the growth in a venture’s asset base. Demanding early profitability is not only good discipline, it is critical to continued success. It ensures that you have truly connected with a job in markets that potential competitors are happy to ignore. As you seek out the early sustaining innovations that realize your growth potential, staying profitable requires that you stay connected with that job. This profitability ensures that you will maintain the support and enthusiasm of the board and shareholders. Internally, continued profitability earns you the continued support and enthusiasm of senior management who have staked their reputation, and the employees who have staked their careers, on your success. There is no substitute. Ventures that are allowed to defer profitability typically never get there.

Notes

1. Many books have been written on the challenges of matching the right money with the right opportunity. Three that we have found to be useful are the following: Mark Van Osnabrugge and Robert J. Robinson, Angel Investing: Matching Startup Funds with Startup Companies: The Guide for Entrepreneurs, Individual Investors, and Venture Capitalists (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000); David Amis and Howard Stevenson, Winning Angels: The Seven Fundamentals of Early-Stage Investing (London: Financial Times Prentice Hall, 2001); and Henry Chesbrough, Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

2. A stream of academic research explores the nature of “first-mover advantage” (for example, M. B. Lieberman and D. B. Montgomery, “First-Mover Advantages,” Strategic Management Journal 9 [1988]: 41–58). This can manifest itself in “racing behavior” (T. R. Eisenmann, “A Note on Racing to Acquire Customers,” Harvard Business School paper, Boston, 2002) in the context of “get big fast” (GBF) strategies (T. R. Eisenmann, Internet Business Models: Text and Cases. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001). The thinking in this field is that in some circumstances it is preferable to pursue a particular strategy very aggressively, even at the risk of pursuing a suboptimal strategy, because of the benefits of establishing a significant market position quickly. The drivers of the benefits of a GBF strategy are strong network effects in customer usage (N. Economides, “The Economics of Networks,” International Journal of Industrial Organization 14 [1996]: 673–699) or other forms of high customer switching costs. The arguments of this school of thought are well articulated and convincing, and suggest strongly that there are conditions when being patient for growth could undermine the long-run potential of a business.

Harvard Business School Professor William Sahlman, who also has studied this issue extensively, has noted in conversations with us that on occasion venture capital investors en masse conclude that a “category” is going to be “big”—even while there is no consensus which firms within that category are going to succeed. This results in a massive inflow of capital into the nascent industry, which funds more start-ups than can possibly survive, at illogical valuations. He notes that when investors and entrepreneurs are caught up in such a whirlwind, they almost have no alternative but to race to out-invest the competition. When the bubble pops, most of these investors and entrepreneurs will lose—and in fact in the aggregate, the venture capital industry loses money in these whirlwinds. The only way not to lose everything is to out-invest and out-execute the others.

The challenge is determining whether or not one is in such conditions. Compelling work by two scholars in particular suggests that network effects and switching costs that are sufficiently strong to overwhelm more prosaic determinants of success arise far less frequently than is generally asserted. See Stan J. Liebowitz and Stephen E. Margolis, The Economics of QWERTY: History, Theory, Policy, ed. Peter Lewin (New York: New York University Press, 2002.) As an example, Ohashi (“The Role of Network Externalities in the U.S. VCR Market 1976–86,” University of British Columbia working paper, available from SSRN) argues that Sony under-invested in customer acquisition in the VCR market, suggesting that it could have been successful had it “raced” harder. Economic modeling suggests that indeed, controlling for product quality, it makes sense to invest more aggressively in customer acquisition when network effects are present than when they are not.

This ceteris paribus assumption with respect to product quality, however, is somewhat heroic, for it assumes away the very reason to be patient and avoid racing. As Liebowitz and colleagues (The Economics of QWERTY) have shown, in the case of the Betamax/VHS battle, a critical element driving customer choice was recording time: Although first to market and offering better video quality, Betamax did not permit two-hour recording times—the minimum typically required to record a movie being broadcast over network television. This turned out to be a critical driver of consumer adoption. JVC’s VHS standard did enable this kind of recording, and met at least minimum acceptable standards for video fidelity. As a result, it was far better aligned with the job to be done, and this superior alignment overcame Betamax’s first-mover advantage. It is doubtful that the incremental market share that a more aggressive marketing spend by Sony might have yielded for the Betamax standard would have beaten back the superior VHS product.

With these caveats in place, it is nevertheless important to recognize the possibility of powerful payoffs to optimal racing behavior, which, in our language, would capture a particular aspect of the job to be done by a given product or service. In the case of network effects, this is captured by the notion that in order for a product to do a job well for me, it must also be doing this same job for many other people. To the extent that such competitive requirements undermine profitability where racing behavior is called for, the need to be patient for profits can be mitigated.

Because the focus of this book is to help corporate managers launch new-growth businesses consistently, we anticipate that they will be caught in GBF racing situations less often than, for example, certain venture capital investors whose strategies might be to participate in big categories.

3. In the language of author and venture capitalist Geoffrey Moore, this is when the “tornado” happens. See Geoffrey A. Moore, Inside the Tornado (New York: HarperBusiness, 1995) and Living on the Fault Line (New York: HarperBusiness, 2000).

4. We refer the reader again to Stanford Professor Robert Burgelman’s outstanding, book-length case study on the processes of strategy development and implementation at Intel, Strategy Is Destiny (New York: Free Press, 2002). In that account, Burgelman emphasizes how important it was that once the winning microprocessor strategy had emerged, Andy Grove and Gordon Moore very aggressively focused all of the corporation’s investments into that strategy.

5. See Alfred Rappaport and Michael Mauboussin, Expectations Investing: Reading Stock Prices for Better Returns (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2001). We mentioned this point in chapter 1, but it merits repeating here. Because markets discount projected growth into the present stock price, companies that deliver what investors have foreseen and discounted will only earn market-average rates of return to shareholders. It is true that over the sweep of their histories, companies that grow at faster rates give higher returns to their shareholders than those that grow more slowly. But the particular shareholders in that history who realize above-average returns are those who find themselves holding the stock when the market realizes that its forecast of the company’s growth was too low.

6. Cost reductions that enable a company to generate stronger cash flows than investors have expected also create shareholder value, of course. We classify these as sustaining innovations because they enable the leading companies to make more money in the way they are structured to make money. Because investors typically can expect ongoing efficiency improvements from any company, our statements here simply reflect the reality that generating shareholder value by exceeding investors’ expectations for operational efficiency typically can only raise share prices to a higher but flat plateau. Tilting the slope of the share price graph upward requires disruptive innovation.

7. This is often true in sustaining situations—it is important to invest aggressively ahead of product launch to ensure that channels are filled and capacity exists to meet expected demand. But this is not the case in disruptive situations.

8. See Corporate Strategy Board, Stall Points (Washington, DC: The Corporate Strategy Board, 1998).

9. This is the theme of an important stream of work by Professor Robert Kaplan and his colleagues that has led them to advocate the use of a tool called the Balanced Scorecard, rather than financial statements, as a measure of an organization’s long-term strategic health. See, for example, Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, The Strategy-Focused Organization (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2001).

10. In asserting that managers ought to let theory guide their actions and not wait until convincing data have become available, we certainly hope that readers do not construe that we are advising managers to fly by the seat of their pants without numbers. Measuring in detail the operating performance of established lines of business, and making decisions based on such data, is crucial to profitable movement up the sustaining trajectory. When engaging in discovery-driven planning for a new disruptive business, the pro forma financial modeling of possible outcomes helps planners understand which assumptions are most important. Our case for theory-driven decisions is grounded in a belief that sound theory can help executives assign strategic meaning to numbers that otherwise might appear to be inconclusive, and to sort the signal from the noise as the data come in.

11. As explored in chapter 6, we would expect that on-the-job management education, as a new-market disruption, will be a modular, nonintegrated industry where the ability to make attractive profits is unlikely to reside in the design and assembly of courses. And yet most of the business schools are attempting to compete in this market by designing and delivering custom executive education courses for large corporations. In our view, the business schools need a major dose of theory. Instead of simply selling cases and articles, a better strategy for them would be to create value-added curriculum modules that would enable tens of thousands of corporate training people to quickly slap together compelling content that helps employees learn exactly what they need to learn, when and where they need to learn it. It would also be critical to enable these trainers to teach these materials in such compelling and interesting ways that none of these on-the-job students has any desire ever to sit through a business school professor’s class again. If history were any guide, if the publishing divisions of the business schools did this, they would ultimately have a far broader impact, and be far more profitable, than their existing on-campus teaching organizations.

12. The literature assessing the performance implications of merger and acquisition activity is enormous, and surprisingly unambiguous. Many studies have revealed that many, and perhaps even most, mergers destroy value in the acquiring firm; see, for example, Michael Porter “From Competitive Advantage to Competitive Strategy,” Harvard Business Review 65, no. 3 (1987), 43–59, and J. B. Young, “A Conclusive Investigation into the Causative Elements of Failure in Acquisitions and Mergers,” in Handbook of Mergers, Acquisitions, and Buyouts, ed. S. J. Lee and R. D. Colman (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1981), 605–628. At best, the only winners appear to be the sellers; see, for example, G. A. Jarrell, J. A. Brickley, and J. M. Netter, “The Market for Corporate Control: The Empirical Evidence Since 1980,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2 (1988): 21–48, and M. C. Jensen and R. S. Ruback, “The Market for Corporate Control: The Scientific Evidence,” Journal of Financial Economics 11 (1983): 5–50. Even if acquisition targets are “well-selected” from a conventional strategic point of view, there is significant evidence to suggest that implementation difficulties can derail the realization of any putative benefits; see, for example, Anthony B. Buono and James L. Bowditch, The Human Side of Mergers and Acquisitions: Managing Collisions Between People, Cultures, and Organizations (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1988), and D. J. Ravenscraft and F. M. Scherer, “The Profitabiliy of Mergers,” International Journal of Industrial Organization 7 (1989): 101–116.

13. We wish to emphasize that our message is not that acquisitions can solve a company’s growth problems. As we note in the text, even the successful acquisition of mature businesses does not change the growth trajectory of a corporation—it just places corporate revenues on a higher but flat plateau. In the late 1990s Cisco followed a very different acquisition strategy from the one we have described at J&J’s MDD business. Cisco’s packet-switching routers had created a powerful wave of disruption versus Lucent and Nortel, which made circuit-switching equipment for voice telephony. Most of Cisco’s acquisitions were sustaining relative to its business model and market position, in that they helped the company move up-market better and faster. They did not constitute platforms for new disruptive growth businesses.

14. This is one of the conclusions of Professor Donald N. Sull’s recent book, Revival of the Fittest (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

15. We worry, in fact, that exactly this sort of reasoning has caused Hewlett-Packard’s senior executives to combine the company’s business units into a few massive organizations. The reorganization facilitated cost cutting, no doubt. But in our view, it can only exacerbate the company’s battle with its values at a time when reigniting growth is very important. At the same time—and this is why good theory is so important—“smallness” versus “bigness” is not the right categorization scheme when thinking about the benefits of these kinds of mergers or the advantages of smallness achieved by organizational separation or spin-outs. Consolidation can yield important cost savings, but as we point out in this chapter, it can corrupt the values needed to pursue potential disruptive opportunities. Smaller organizations—or big organizations that are blown apart into a series of smaller organizations—might have an easier time dealing with the challenges of embracing disruption-friendly values, but as we point out in chapters 5 and 6, organizations must also cope with the demands of architectural interdependencies, which can often require larger, more integrated organizations. In our view, it’s not so much about making trade-offs; that is, accepting inevitable compromises, as it is about recognizing the circumstances one is in and adopting the appropriate solution to the most pressing problem.

16. We have often been asked how much money a venture should be allowed to lose, and how much time it should take until profits should be expected. There can, of course, be no rigid rules, because the fixed-cost intensity of each business will vary. Mobile telephony was a disruptive growth business that entailed large fixed-cost investments, and hence more significant losses than would many others. In making these recommendations, we simply hope to offer to executives the guiding principle that losing less is more.

17. Honda’s experience is summarized on pages 153 to 156 of The Innovator’s Dilemma. That account has been condensed from a case study by Evelyn Tatum Christensen and Richard Tanner Pascale, “Honda (B),” Case 9-384-050 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 1983).

18. Searching for unanticipated successes, rather than seeking to correct deviations from a plan, is one of the most important principles that Peter F. Drucker taught in his classic book Innovation and Entrepreneurship (New York: Harper & Row, 1985).

19. This tendency to refocus immediately on the core when things get bad, even at the expense of the long-term solutions to the problem that caused the core to get sick, is known among behavioral psychologists as “threat rigidity.” See chapter 4 for more on this.

20. Fiore’s experiences are detailed in Clayton M. Christensen and Tara Donovan, “Nick Fiore: Healer or Hitman? (A)” Case 9-601-062 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2000).

21. Presentation by Dr. Nick Fiore to Harvard Business School students, 26 February 2003.

22. Professor William Sahlman of the Harvard Business School has studied the phenomenon of venture capital “bubble” investing for two decades. He observes that when many venture investors conclude that they need to have strong investment positions in a “category,” investors develop “capital market myopia”—a view that does not consider the impact that other firms’ investments will have on the probability that their individual investment will succeed. When massive amounts of available venture capital are focused on an industry where investors perceive steep scale economies and strong network effects, the funds and the companies in which they invest are compelled to engage in “racing” behavior. Firms seek to dramatically outspend the competition, because it is a company’s relative spending rate and its relative execution capability that drive success. Sahlman notes that once a race like this has started, venture funds have no option but to engage in that behavior if they want to participate in that investment category. Sahlman has observed that between the mid-1980s and the early 1990s—the period following the first of these investment bubbles—the returns to venture capital were zero. We have seen a similar decline in venture returns in the years following the dot-com and telecommunications investment bubble in the late 1990s.

23. Big-ticket investing of money that is impatient for profit and growth is very appropriate in later stages of step 1 of the spiral, when the company needs to focus deliberately on a winning strategy that has become clear. Interestingly, Bain Capital, which has been one of the most successful investment firms over the past decade, made this transition very effectively. Bain started out making rather small venture investments. It provided the start-up funding for Staples, the office superstore, for example. It was so successful with its first fund that investors simply poured as much money into subsequent funds as Bain would let them. This meant that the firm’s values changed, and it could no longer prioritize small investments. In contrast to the behavior of the venture funds in the bubble, however, Bain stopped making early-stage investments as it got bigger. It became a later-stage private equity investor, and continued to perform magnificently. In the parlance of the model of theory building we presented in the introduction, as these investment funds grow, they find themselves in different circumstances. The strategies that led to success in one circumstance can lead to disaster in another. Bain Capital changed strategy as its circumstances changed. Many of the venture capital funds did not.