C H A P T E R 6

Booting Ubuntu for the First Time

Now that Ubuntu is installed, you'll no doubt want to get started immediately, and that's what Part 3 of this book is all about. In later chapters, we'll present specific details of using Ubuntu and getting essential hardware up and running. We'll also show you how to personalize the desktop so it works in a way that's best for you on a day-to-day basis. But right now, the goal of this chapter is to get you doing the same things you did under Windows as quickly as possible.

This chapter explains how to start up Ubuntu for the first time and work with the desktop. It also shows how some familiar aspects of your computer, such as using the mouse, are slightly enhanced under Ubuntu.

Starting Up

If you've chosen to dual-boot with Windows, the first Ubuntu screen you'll see is the boot loader menu, which appears shortly after you switch on your PC. If Ubuntu is the only operating system on your hard disk, you need to hold the Shift key during system startup to access this boot menu, but you won't need to do so unless you want to access the recovery mode boot settings. In fact, if Ubuntu is the only operating system on your computer, you can skip to the next section of this chapter.

![]() Note The boot loader is actually a separate program called Grub, which has been updated to version 2 since Ubuntu 9.10. This program kicks off everything and starts Ubuntu.

Note The boot loader is actually a separate program called Grub, which has been updated to version 2 since Ubuntu 9.10. This program kicks off everything and starts Ubuntu.

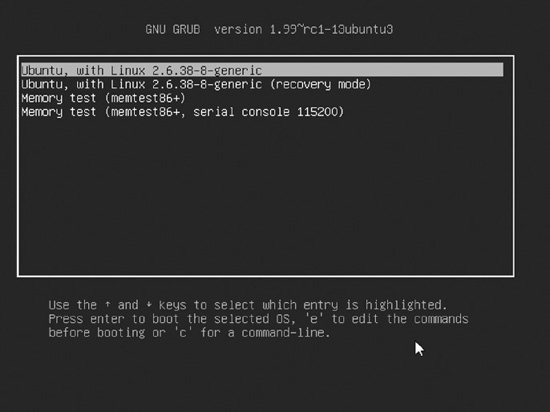

The boot loader menu you see when your PC is set to dual-boot has three or four choices, as shown in Figure 6-1. The top one is what you need to boot Ubuntu. The Ubuntu option will be selected automatically within 10 seconds, but you can press Enter to start immediately.

Figure 6-1. The default choice is fine on the boot menu, so press Enter to start Ubuntu.

You should find that you also have an entry for Windows, located at the bottom of the list and labeled with whichever version of the OS you have installed. To boot into Windows, simply use the cursor keys to move the selection to the appropriate option and then press Enter.

![]() Note From the GRUB menu, you can also select to run a memory test. If your computer frequently crashes without specific reason, bad memory might be the reason. If that happens, run the memory check to find out if it's time to replace some faulty memory chips.

Note From the GRUB menu, you can also select to run a memory test. If your computer frequently crashes without specific reason, bad memory might be the reason. If that happens, run the memory check to find out if it's time to replace some faulty memory chips.

You should also see an entry ending in “(recovery mode).” This is a little like Safe Mode within Windows. If you select recovery mode, Ubuntu will boot to a text mode menu with six options:

resume—Resume normal boot: This option allows you to boot normally, as if you didn't need to fix anything at all. However, the big difference with this option compared to a graphical boot is that Ubuntu boots in text mode, in which system messages scroll past as Ubuntu is starting up. If you have problems with booting Ubuntu, you can run in recovery mode and choose this option to find error messages in the boot process.

clean—Try to make free space: This option forces the boot loader to try to make free space on the disk.

dpkg—Repair broken packages: This option tries to repair the software installed on your computer.

failsafeX-Run in failsafe graphic mode—This option allows you to log in with low resolution and a limited number of colors, so you can run a display configuration utility to test various display settings and choose a configuration that works well with your hardware, and troubleshoot your display problems.

fsck-Reboot into file system check— Enables you to check and optionally repair Linux file systems. This operation is better done with the file systems unmounted, so when you choose this option, the system will reboot and run the filesystem check on default partitions.

Grub—Update Grub loader:Forces Grub (the program that presents you this boot menu) to query the operating systems installed in your hard disks and to recreate the list it presents at startup.

netroot—Drop to shell prompt with networking: Like the option “root” but with the networking features fully functional.

root—Drop to root shell prompt:This option boots with conservative system settings and then presents you with a command-line prompt in administrator mode (you run as the root user—a special user account that has absolute power over the entire system, so try to avoid booting to this option if you can do so, and be very careful when you don't have any other option but to use the root shell prompt). The typical usage for this prompt is to change the passwords of users if they forget their passwords, to free up disk space to run normally, and to uninstall buggy software to bring back system stability. The system commands that can be used for recovery are

passwd(to change passwords),mv(to move files and folders),rm(to delete files and folders),cp(to copy files and folders),mkdir(to create a new folder), anddpkg(to install or remove software). These and other commands are discussed further in Appendix A.

When you update your system software, you might find that new entries are added to the boot menu list. This is because the kernel has been updated. The kernel is the central system file that Ubuntu relies on, and essentially, the boot menu exists to let you choose between different kernels. Almost without exception, the first (topmost) entry is the one you'll want each time to boot Ubuntu, because this will always use the most recent version of the kernel, along with the latest versions of other system software. The other entries will start the system with older versions of the kernel and are provided in the unlikely situation that the latest kernel causes problems.

![]() Note All operating systems need a boot loader, even Windows. However, the Windows boot loader is hidden and simply starts the OS. Under Ubuntu, the boot loader usually has a menu so you can select Linux or perhaps an option that lets you access your PC for troubleshooting problems. When you gain some experience with Ubuntu, you might choose to install two or more versions of Linux on the same hard disk, and you'll be able to select among them by using the boot menu.

Note All operating systems need a boot loader, even Windows. However, the Windows boot loader is hidden and simply starts the OS. Under Ubuntu, the boot loader usually has a menu so you can select Linux or perhaps an option that lets you access your PC for troubleshooting problems. When you gain some experience with Ubuntu, you might choose to install two or more versions of Linux on the same hard disk, and you'll be able to select among them by using the boot menu.

Logging In

After Ubuntu has booted, which shouldn't take long,, you will see the login screen, as shown in Figure 6-2. Here you enter the username and the password you created during the installation process. If during installation you selected to be automatically logged in at startup, then you will not see this screen and will be presented with the desktop right away.

Clicking the Shutdown Options button in the bottom-right corner of the screen brings up a menu from which you can opt to reboot the system or shut it down. Next to this button are the clock and the Universal Access Preferences button, which allows you to enable accessibility features such as the on-screen keyboard and the magnifier.

The user account you created during installation is similar to what Windows refers to as an administrator account. This means that the within the account you use on a day-to-day basis you can also change important system settings and reconfigure the system. However, the main difference between Ubuntu and Windows is that you'll need to enter your password to make any serious changes, rather than clicking in a confirmation dialog box, as with Windows Vista or Windows 7 (of course, Windows XP doesn't have any kind of confirmation requirement at all!).

Don't worry about damaging anything accidentally; trying to reconfigure the system or access a serious system setting will invariably bring up a password prompt. You can simply click the Cancel button if you don't want to continue.

![]() Note Unlike some versions of Linux, Ubuntu doesn't encourage the user to use an actual root (administrator) account. This is even disabled by default. Instead, it operates on the principle of certain ordinary users adopting superuser privileges that allow them to administer the system when they need to. Those are called sudoers. In UNIX terms, sudo is short for superuser do, meaning to perform a task as the superuser. A sudoer is a user account enabled to execute sudo for certain tasks, as defined in the sudoers file. The user account you create during setup has these privileges.

Note Unlike some versions of Linux, Ubuntu doesn't encourage the user to use an actual root (administrator) account. This is even disabled by default. Instead, it operates on the principle of certain ordinary users adopting superuser privileges that allow them to administer the system when they need to. Those are called sudoers. In UNIX terms, sudo is short for superuser do, meaning to perform a task as the superuser. A sudoer is a user account enabled to execute sudo for certain tasks, as defined in the sudoers file. The user account you create during setup has these privileges.

Figure 6-2. Select or type your username, enter your password, and then press Enter to log in.

Exploring the Desktop

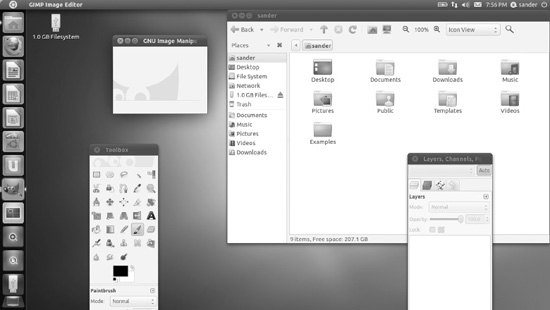

After you've logged in, you'll see the welcoming theme of the new Unity interface, as shown in Figure 6-3. If you have used any previous release of Ubuntu, and if you have the proper hardware,1 you will notice a great deal of changes.

Feel free to click around and see what you can discover. There's little chance of your doing serious damage, so let yourself go wild and play around with your new OS! However, be careful if any dialog boxes ask you to type your password—this indicates that you've clicked an action that has the potential to change the system in a fundamental way.

__________________

1The Unity interface has hardware requirements listed on the following link: https://wiki.ubuntu.com/DesktopExperienceTeam/UnityHardwareRequirements. If your computer fails to meet them, you will be presented with the traditional Gnome-panel-based version of the interface. You can still install a version of the Unity interface with lesser hardware requirements (also known as Unity 2D); you will learn how to install it in Chapter 9.

Figure 6-3. A clean Ubuntu desktop—this is your first view of the new OS.

First Impressions

The first thing you'll notice is that the desktop is clean compared to Windows. You don't have a lot of icons littering the screen.

Of course, you can fill the desktop with all the icons you want. As with Windows, you can save files to the desktop for easy access. In addition, you can click and drag icons from any of the menus onto the desktop in order to create shortcuts.

UNITY: THE NEW FACE OF UBUNTU

![]() Note If you're dual-booting with Windows, you might see an icon at the top left of the Ubuntu desktop that will let you access your Windows files. On one system, it was identified as sda1. Double-click the icon to view the Windows file system. Similarly, if you have a memory card reader or digital camera plugged in your PC, you might see desktop icons for them too, and any inserted CD/DVD discs will also be represented by desktop icons.

Note If you're dual-booting with Windows, you might see an icon at the top left of the Ubuntu desktop that will let you access your Windows files. On one system, it was identified as sda1. Double-click the icon to view the Windows file system. Similarly, if you have a memory card reader or digital camera plugged in your PC, you might see desktop icons for them too, and any inserted CD/DVD discs will also be represented by desktop icons.

By default, the Ubuntu desktop interface is clean and neat, with only a few elements vying for attention. Let's describe them quickly now; you can find a more detailed description later in this chapter.

Top Panel—Natty includes the traditional horizontal strip at the top of the desktop. As in previous versions of Ubuntu, it displays at the right the application status indicators, the clock, the Me menu, and the Session menu. But to the left, you will notice that the traditional three menus (Applications, Places, and System) are missing, or replaced by a single Ubuntu logo, which is called the Home Button (or, more graphically, the “Big Freakin' Button”). Clicking the Home Button will open the Unity dash, with a Search dialog box and shortcuts to the most popular applications.

Unity launcher—Maybe the central part of the Unity user interface is the Unity launcher, which by default shows on the left part of the screen. When your current application encroaches the area where the Unity launcher is located, it will auto-hide. Unity launcher reappears when your application workspace leaves the area where the Unity launcher is located. The Unity launcher is a vertical strip that, when visible, is located below the Home Button and contains icons representing various applications or system components. Those icons are called launchers, and when selected they open the specified application or let you access more options for the specific system component. Those launchers enable you to access files and folders on your computer (Home folder, Files & Folders), browse the Web (Firefox web browser), work on documents (LibreOffice Writer, Calc, and Impress), install new software (Ubuntu Software Center), access online services (Ubuntu One), switch between workspaces (Workspace Switcher), open applications (Applications), and view the contents of the Trash. You can add your own launchers, as you will see in Chapter 9. Open Applications will automatically add an icon to the Unity launcher that you can use to access the application when it is not active at the moment.

The mouse works mostly as it does in Windows, in that you can move it around and click on things. For the most part, single- and double-clicking work exactly as they do in Windows. You can also right-click virtually everything and everywhere to bring up context menus, which usually let you alter settings. And you should find that the scroll wheel in between the mouse buttons lets you scroll windows.

Something that might catch your attention the first time you open a window in Lucid Lynx is the placement of the familiar Maximize, Minimize, and Close buttons. They are placed to the left of the top bar, instead of to the right as is customary in Windows and OS X. Clicking the Close button ends each program, as in Windows. And a new improvement developed for Natty Narwhal is that the top bar of any application's window, when it is maximized, is merged with the top panel, using the most part of the top panel that is usually empty.

Whenever Ubuntu is busy, an animated, circular icon appears that is similar in principle to the hourglass icon used in Windows. It also appears when programs are being launched.

![]() Caution Bear in mind that Ubuntu isn't a clone of Windows and doesn't try to be. Although it works in a similar way—by providing menus and icons and containing programs within windows—there are differences and refinements that may trip you up as you explore.

Caution Bear in mind that Ubuntu isn't a clone of Windows and doesn't try to be. Although it works in a similar way—by providing menus and icons and containing programs within windows—there are differences and refinements that may trip you up as you explore.

Exploring the Top Panel and the Unity Launcher

The two central parts of the Ubuntu desktop are the top panel and the Unity launcher. The top panel, as we mentioned earlier, is the horizontal strip at the top of the screen. The Unity launcher is the vertical strip at the left of the screen that has launchers for the most used components of the system.

They are extremely useful and highly customizable. Most of the operations you will ever need to access on Ubuntu are available through those two, so mastering them early on is of great help (to read more about personalizing the top panel and the Unity launcher, refer to Chapter 9). The exact view is determined by what you have installed on your computer. Following is a list of some of the most important parts of your graphical desktop.

Home Button: The Home Button is the Ubuntu icon at the far left of the top panel. When clicked, it allows you to access the Unity dash, where you can search for and open some of the most common applications.

Application launchers: In the Unity launcher, you'll find icons that represent applications. By default, the Firefox web browser, and LibreOffice's Writer, Calc, and Impress find their home here. You can create your own launchers for existing applications, but if you overpopulate the Unity launcher, it can be more difficult to find your applications. When you click one of those icons the corresponding application starts.

Home folder and Files & Folders launchers: These two launchers, which are the first and the last of the launchers (not counting the Trash, which is at the bottom of the Unity launcher) will allow you to open Nautilus, the file explorer. Nautilus is further explained in Chapter 10.

Ubuntu Software Center: This launcher, sixth in the Unity launcher, will open the Ubuntu Software Center and allow you to install new applications. It is explored in more detail in Chapter 20.

Ubuntu One: This launcher lets you access configuration for the cloud services described in Chapter 15. With Ubuntu One, you can back up files and other data (such as music collections, your contact information, or your Firefox bookmarks and Tomboy notes) to the Web, and synchronize them across many computers,

Workspace Switcher: The Workspace Switcher is used to move between virtual desktops, described later in this chapter.

Applications: This launcher, which is gray with a plus sign at the middle, is the go-to place when you want to open an application. It replaces the Applications and System menus of the previous Ubuntu releases. When selected, it opens the Applications dash, which contains, at the top, a Search dialog box that you can use to narrow the list of applications shown. You can also select the category of the application with the drop-down list located at the right of the Search dialog box. There will be three sections for applications in the dash: the Most Frequently Used applications, the Installed applications (which is the most important section), and the Apps Available for Download, which are not installed but just a few clicks of the mouse away. A quick tip: you can create an application launcher by dragging the icon of the application to the Unity launcher.

Off button: The right-most item in the top panel is the Off button, about which more details are given later in this chapter. You will notice sometimes that the Off button changes its color to red. This is an indication that a change has been made to the system that requires you to reboot the computer. This can happen, for example, when you install the latest updates to Ubuntu.

Me menu: The Me menu, indicated by your username on the panel and located to the left of the Off button—allows you to easily set your status for various IM clients and post to social network sites like Facebook or Twitter without having to log in to them. Its functionality is explained in depth in Chapter 15.

Clock: The clock is located at the top right of the screen. Clicking it brings up a handy monthly calendar. Click it again to hide this display. Click Add Event to add an entry to the Evolution calendar from here (this calendar is explained in Chapter 14). Click Time & Date Settings to configure the time zone and how the time and date information is displayed.

Indicator applet: The Indicator applet, represented by an envelope icon next to the clock, allows you to configure instant message (IM), mail, and broadcast accounts, and is used by those same accounts to inform you when a change has occurred, such as new incoming mail or an IM from one of your contacts. There is also a shortcut to Ubuntu One.

Notification area: This is similar to the Windows system tray. Programs that like to hang around in memory, such as Banshee the media player or Skype, add icons in this top-right area to allow quick access to their functions. The Software Update Notifier appears in this area to let you know that software updates are available (similar to Windows Update). Network Manager displays an icon here when you are connected to the network. The Volume Control applet is here too. Usually, you simply need to click (or right-click) their icons to access the program features.

Notifications: In addition to the notification area, Ubuntu also has a pop-up, short-term notification system that is used to keep you informed of changes to your system's volume, screen brightness, network availability, IM friend status, and other useful things. You might want to disable some notifications if they start to annoy you.

Trash: At the bottom of the Unity panel is the Trash icon. Dragging files or folders into this icon causes them to be moved to the trash. From here you can also empty the trash or view its contents.

![]() Note There's one important difference between the Recycle Bin in Windows and Ubuntu's Trash. By default, the Recycle Bin uses only 10 percent of the remaining space on a hard disk. After this, the oldest items are automatically deleted. With Ubuntu's version, the only limit on the contents is the remaining free space on the disk. Nothing will ever be removed from the Trash unless you specifically choose to remove it.

Note There's one important difference between the Recycle Bin in Windows and Ubuntu's Trash. By default, the Recycle Bin uses only 10 percent of the remaining space on a hard disk. After this, the oldest items are automatically deleted. With Ubuntu's version, the only limit on the contents is the remaining free space on the disk. Nothing will ever be removed from the Trash unless you specifically choose to remove it.

Shutting Down or Restarting Ubuntu

You can shut down or reboot your PC by clicking the Off button in the top-right corner of the screen. On many laptops and desktops, you can also briefly press the on/off button on the computer. The former method presents you with a selection of options in a drop-down list, while the latter launches a dialog box showing icons for various options, as shown in Figure 6-4.

Figure 6-4. A variety of shutdown operations are available, some allowing for a quick resumption later on.

Note that not all the options appear if you use the hardware method to close down. The options in the drop-down list are as follows:

Lock Screen: This enables the screen saver and password-protects the system. The only way to leave Lock Screen mode is to enter the user's password into the dialog box that appears whenever you move the mouse or press a key.

Guest Session: This launches a new guest session of the desktop. It is ideal for employees who are temporarily using a company's PC, for example, or for friends who visit and want to check their e-mail or Facebook without leaving any trace on your PC. Any files downloaded on a guest account are deleted when the user logs out.

Switch From <username…>: If multiple users are defined on the system (Chapter 21 discusses how to add user accounts), this option allows others to log in without closing down the original user's account. To switch back to the original user, choose Switch User again or log out the second user. The original user will need to enter their password to regain access.

Log Out: This option logs you out of the current user account and returns you to the Ubuntu login screen. Any open programs will be shut down automatically.

![]() Caution During shutdown or logout operations, Ubuntu sometimes automatically shuts down applications that contain unsaved data without prompting you, so you should always save files prior to selecting any of the options here.

Caution During shutdown or logout operations, Ubuntu sometimes automatically shuts down applications that contain unsaved data without prompting you, so you should always save files prior to selecting any of the options here.

Suspend: This uses your computer's suspend mode, in which most of the PC's systems are powered down except for the computer's memory. Suspend mode is designed to save power and allow a quick reactivation of the PC. Not all computers support suspend mode, however, so you should experiment to see if your computer works correctly. Ensure that you save any open files before doing so. If your PC goes into suspend mode but fails to wake up when you shake the mouse or push keys, you may need to reboot. This can often be done by holding down the power button for about five seconds.

Hibernate: This saves the contents of the computer's memory to the hard disk and then completely powers down the computer. When the computer is reactivated, the user chooses to start Ubuntu as normal, and the memory contents are read in from disk. This allows a faster startup and allows users to resume from where they were last working. For the hibernate feature to work, the swap file needs to be as large as or larger than the main memory. Ubuntu's installation program should have automatically done that, but if you didn't dedicate enough disk space to Ubuntu when repartitioning, it might not have been able to do so. The only way to find out is to attempt to hibernate your system and see whether it works.

![]() Caution Some users have reported that their computer is sometimes unable to “wake” from hibernation, so you should save any open files before hibernating as insurance against the unlikely prospect that this happens. We've seen this happen a few times, although hundreds of other times it's worked fine.

Caution Some users have reported that their computer is sometimes unable to “wake” from hibernation, so you should save any open files before hibernating as insurance against the unlikely prospect that this happens. We've seen this happen a few times, although hundreds of other times it's worked fine.

Restart: This option shuts down Ubuntu and then restarts the computer.

Shut Down: This shuts down Ubuntu and then powers off your computer, provided its BIOS is compatible with the standard shutdown commands. (All computers bought within the past five years or so are compatible; if you find that the computer hangs at the end of the Ubuntu shutdown procedure, simply turn it off manually via the power switch.)

Only the last four of these options are available in the Shut Down the Computer dialog box, opened via the hardware shutdown button or by pressing the Ctrl+Alt+Del combination of keys. If you leave the computer after pushing this button, it will pause for 60 seconds and then shut down.

Quick Desktop Guides

Refer to Figure 6-5 for an overview of the Ubuntu Desktop. In this figure, you can see an open browser window, a program window, and the default desktop components, such as the Unity pane in the left part of the screen. The Ubuntu Desktop has been completely redesigned, so it's best that you don't try to compare it to what you may know from a Windows environment!

Figure 6-5. The Ubuntu desktop has been largely redesigned for this release of Ubuntu.

Running Programs

Starting a new program is easy. Just click the Applications launcher in the Unity panel and then choose a program from the list. The applications interface, shown in Figure 6-6, is grouped into three parts in which you can find your Most Frequently Used applications, the Installed applications, and some popular applications that are available for download. Also, you can click the All Applications link in the upper right part of the screen to get access to all software that is installed on your computer.

If you want to start the web browser or the LibreOffice applications (arguably some of the most popular programs offered by Ubuntu), you can click their icons on the Unity panel.

Figure 6-6. The programs on the Applications launcher are grouped into various categories, which you can filter.

Working with Virtual Desktops

Windows works on the premise of everything taking place on top of a single desktop. When you start a new program, it runs on top of the desktop, effectively covering up the desktop. In fact, all programs are run on this desktop, so it can get a bit confusing when you have more than a couple of programs running at the same time. Which Microsoft Word window contains the document you're working on, rather than the one you've opened to take notes from? Where is that My Computer window you were using to copy files?

Ubuntu overcomes this problem by having more than one desktop area. By using the Workspace Switcher tool, located on the Unity launcher, you can switch between two or more virtual desktops, as shown in Figure 6-7. This is best explained by a demonstration:

- Make sure you're currently on the first virtual desktop (open the Workspace Switcher and select the upper left panel), and start up the web browser from the Unity launcher.

- Click the second square on the Workspace Switcher. This switches you to a clean desktop, where no programs are visible—desktop number two.

- Start up the file browser by clicking the upper button in the Unity launcher—the one that looks like a folder icon. A file browser window appears.

- Click the first square in the Workspace Switcher again. You should switch back to the desktop that is running the web browser.

- Click the second square, and you switch back to the other desktop, which is running the file browser.

![]() Tip You can hold down Ctrl+Alt and press the up, down, left, and right cursor keys to switch between virtual desktops.

Tip You can hold down Ctrl+Alt and press the up, down, left, and right cursor keys to switch between virtual desktops.

You can click and drag the small representations of an application window from one workspace to another in the Switcher itself. The Workspace Switcher provides a way of organizing your programs and also reducing the clutter. You can experiment with virtual desktops to see whether you want to organize your work this way. Some people swear by them.

Using the Mouse

As noted earlier, the mouse works mostly the same under Ubuntu as it does under Windows: a left-click selects things, and a right-click usually brings up a context menu. Try right-clicking various items, such as icons on the desktop or even the desktop itself.

![]() Tip Right-clicking a blank spot on the desktop and selecting Create Launcher lets you create shortcuts to applications. Clicking Create Folder lets you create new empty folders. You can also use Create Document

Tip Right-clicking a blank spot on the desktop and selecting Create Launcher lets you create shortcuts to applications. Clicking Create Folder lets you create new empty folders. You can also use Create Document ![]() Empty File if for some reason you want to create an empty file.

Empty File if for some reason you want to create an empty file.

You can use the mouse to drag icons on top of other icons. For example, you can drag a file onto a program icon in order to run it. You can also click and drag in certain areas to create an “elastic band” and, as in Windows, this lets you select more than one icon at once.

You can resize windows by using the mouse in much the same way as in Windows. Just click and drag the edges and corners of the windows. In addition, you can double-click the title bar to maximize and subsequently restore windows.

Ubuntu also makes use of the third mouse button for middle-clicking. You might not think your mouse has one of these but, actually, if it's relatively modern, it probably does. Such mice have a scroll wheel between the buttons, and this can act as a third button when pressed.

In Ubuntu, the main use of the middle mouse button is in copying and pasting, as described in the next section. Middle-clicking also has a handful of other functions; for example, middle-clicking the title bar of any open window will switch to the window underneath.

![]() Tip If your mouse doesn't have a scroll wheel, or if it has one that doesn't click, you can still middle-click. Simply press the left and right mouse buttons at the same time. This emulates a middle-click, although it takes a little skill to get right. Generally speaking, you need to press one button a fraction of a second before you press the other button.

Tip If your mouse doesn't have a scroll wheel, or if it has one that doesn't click, you can still middle-click. Simply press the left and right mouse buttons at the same time. This emulates a middle-click, although it takes a little skill to get right. Generally speaking, you need to press one button a fraction of a second before you press the other button.

Cutting and Pasting Text

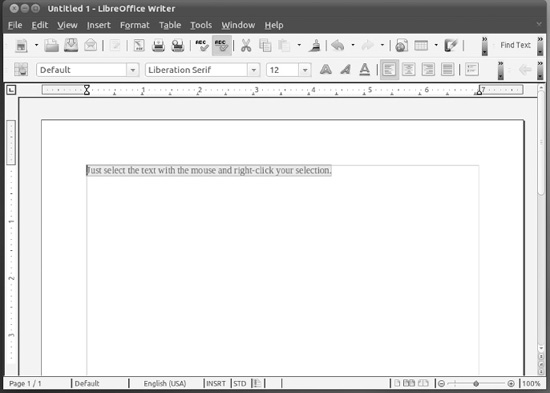

Ubuntu offers two separate methods of cutting and pasting text. The first is identical to Windows. In a word processor or another application that deals with text, you can click and drag (or double-click) the mouse to highlight text, right-click anywhere on it, and then choose to copy or cut the text. In many programs, you can also use the keyboard shortcuts of Ctrl+X to cut, Ctrl+C to copy, and Ctrl+V to paste.

However, there's a quicker method of copying and pasting. Simply click and drag to highlight some text and then immediately click the middle mouse button where you want the text to appear. This copies and pastes the highlighted text automatically, as shown in Figure 6-7.

This special method of cutting and pasting bypasses the usual clipboard, so you should find that any text you've copied or cut previously should still be there. The downside is that it doesn't work across all applications within Ubuntu, although it does work with the majority of them.

Figure 6-7. Highlight the text and then middle-click to paste it instantly.

Summary

This chapter covered booting into Ubuntu for the first time and discovering the desktop. We looked at starting programs, working with virtual desktops, using the mouse on the Ubuntu desktop, and much more. You should be confident in some basic Ubuntu skills and ready to learn more!

In the next chapter, you'll look at getting your system up and running, focusing on items of hardware that you may encounter in day-to-day use.