Chapter 37. Events

event (î-vênt’): something that happens: a noteworthy occurrence or happening: something worthy of remark: an unusual or significant development. (Paraphrased from Webster’s Third.)

Events are what drive Perl/Tk programs. In the past I’ve described

these events superficially, sweeping lots of detail under the

MainLoop rug, all for the sake of simplicity.

MainLoop is our friend, since it’s all that is needed

for nearly every Perl/Tk program. But sometimes it’s not enough.

Today’s featured program is a simple Pong-like game sporting a new

widget derived from the Canvas class, which we’ll compare to the

Odometer composite widget described in The Mouse

Odometer. Instead of using MainLoop, our

Pong game handles events itself with

DoOneEvent.

Before discussing Pong, we’ll examine some other programs,

including a simple animation called neko,

demonstrating the Photo widget and some other Tk commands.

Tk defines four broad event categories: X, timer, input/output, and idle. X events are generated in response to mouse motion, button and keyboard actions, and window changes. You already know that many of these events have built-in Tk bindings, and that you can create your own bindings, so all you need to do is define the callback to handle the event. (There are lots of other X events, which we’ll examine in detail in subsequent articles.) Timer events are used for periodic occurrences, from blinking items to animating images. Input/output events help prevent your application from freezing when reading and writing to terminals, pipes, or sockets. Finally, idle events are low priority callbacks invoked only when all events from the previous three event queues have been processed. Tk uses the idle events queue to redraw widgets, since it’s generally a bad idea to redisplay a widget after every change of state. By deferring redraws until there is nothing left to do, widgets presumably reach their steady state. The result is improved performance and a flicker-free screen.

Timer Events

In The Mouse Odometer we saw a useful idiom for scheduling asynchronous tasks:

modo();

...

sub modo { # Do stuff, then reschedule myself.

$MW->after->($MILLISECOND_DELAY, &modo);

}Before modo returns, it uses

after to schedule a timer event and define the handler (callback). This

idiom is so common that Perl/Tk provides repeat as a

shortcut, so the above code can be condensed like so:

$MW->repeat->($MILLISECOND_DELAY, &modo);

A working example named rpt is available at

http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/tpj2.

Tk uses timer events to flash the insertion cursor for entry widgets. After the widget gets the

keyboard focus, it displays the cursor and queues a timer callback.

Then the callback erases the cursor and the cycle repeats, several

times per second. This technique is often used to flash alert messages

or special buttons. You can use repeat, but this is

the idiom you’ll almost always see:

my $b = $MW->Button(-text => 'Hello World!', -command => &exit)->pack;

flash_widget($b, -background, qw(blue yellow), 500);

MainLoop;

sub flash_widget { # Flash a widget attribute periodically.

my ($w, $opt, $val1, $val2, $interval) = @_;

$w->configure($opt => $val1);

$MW->after($interval, [&flash_widget, $w, $opt, $val2, $val1, $interval]);

}As you see, the code is quite simple. On the first call to

flash_widget, the button’s background is configured

blue. A timer event is then scheduled, reversing the background

colors, so next time the widget is configured yellow. The periodic

change in background color every 500 milliseconds yields the desired

flashing effect. A working example, named flash, is

on the book’s web site.

You can also perform crude animations with nothing more than

standard Tk timer events. To demonstrate, I created a basic

neko program, using frames borrowed from Masayuki

Koba’s well known xneko. In case you’re unfamiliar

with xneko, a cat chases the cursor around the

window. When you stop moving the cursor, the cat yawns and settles

down to take a nap. When the cursor moves again, Neko wakes up and

resumes the chase. My rendition of neko doesn’t

follow the cursor and moves solely in one dimension.

In the U.S., television creates the illusion of motion by

flashing 30 full images per second. Movies show 24 images per second,

but flash each image three times to lessen the flicker.

Psychophysicists have determined that 10 images per second is, on

average, the minimum number needed to perceive motion, so that’s what

we’ll use for neko. I don’t actually have ten

images to show, just two: one of Neko with his feet together, and one

with his feet apart.

When you run neko, Figure 37-1, depicting the six frames

used by the application, is momentarily displayed.

To make use of these frames we need to create Tk images. In Tk parlance, an image is just another Tk object with special methods for image manipulations. Once created, images are then imported into other widgets, such as a button, canvas or label. For example, this code creates a button with Neko’s icon on it instead of text:

my $i = $MW->Photo(-file => 'images/icon.ppm'),

my $b = $MW->Button( -image => $i, -command => sub {print "Meow

"})->pack;Images come in two flavors: bitmaps, which

have only two colors, and photos, which have many

colors or shades of grey. The six neko frames were

originally plain X bitmaps, but have since been converted to colorized

PPM files, a format (such as GIF) suitable for input to the

Photo command.

The canvas widget provides an ideal backdrop for the animation, since images can be drawn on it and moved using standard canvas methods. Here’s the code that created much of Figure 37-1:

# Create the six Photo images from the color PPM files and display

# them in a row. The canvas image IDs are stored in the global array

# @IDS for use by the rest of the Neko code. For instance, to perform

# a canvas operation on the Neko icon, simply fetch its item ID from

# $IDS[5]. Sorry for using hardcoded values, but this is just "proof

# of concept" code!

my $x = 125;

foreach ( qw(left1 left2 sleep1 sleep2 awake icon) ) {

push @IDS, $C->createImage($x, $SCAMPER_Y,

-image => $MW->Photo(-file => "images/$_.ppm"));

$x += 50;

}

# Wait for the main window to appear before hiding the Neko

# frames. (Otherwise you might never get to see them.)

$MW->waitVisibility($MW);

$MW->after(2000, &hide_nekos);

MainLoop;An immediate problem arises: the animation demands that only one frame be visible at any

point in time, so we need to hide arbitrary frames (including the six

frames currently on the canvas). One way might be to create and delete

the images continually, but that’s messy. Instead,

neko uses a trick based on the canvas

display list.

Tk uses the display list to control the order in which canvas

items are displayed, so that items created later are displayed after

items created earlier. If two items are positioned at the same (or

overlapping) coordinates, the item earliest in the display list is

obscured because the other item is displayed on top of it. Thus, the

rightmost item in Figure 37-1,

the neko icon, is on top of the display list. We’ll

move the icon off to the side, hide all inactive images under it, and

no one will be the wiser!

my($i, $done, $rptid, $cb) = ($#IDS, 0, 0, 0);

$cb = sub {

my($ir) = @_;

hide_frame $IDS[$$ir--];

$done++ if $$ir < 0;

};

my $rptid = $MW->repeat(1000 => [$cb, $i]);

$MW->waitVariable($done);

$MW->afterCancel($rptid);There’s more to these five statements than meets the eye, so

let’s examine them one by one. We want to move the icon image first,

so set $i to its index in the

@IDS array. Even though the icon is the first image

moved, it will nevertheless obscure the remaining images because it’s

at the end of the display list.

The second statement defines a timer callback, $cb, whose sole

purpose is to hide one neko frame, decrement the

index $i and set the $done flag

after the last image has been moved. Here’s where it gets tricky: the

parameter passed to the anonymous subroutine is not the value of

$i itself, but $$i, a

reference to $i. Passing

$i directly would only postdecrement the copy local

to the subroutine, $ir, and not the “real”

$i. Thus, only the icon frame would be moved, and

the callback would never set the $done flag.

The repeat queues a timer event that, until canceled, repeats once a second,

forever. However, the callback has been designed to modify the

$done variable after the last image has been

hidden. Notice that repeat, like all asynchronous

timer event scheduling methods, returns a

timer ID, used to subsequently remove the event

from the timer queue.

The waitVariable waits until the value of

$done changes. Although the application’s flow is

logically suspended, it still responds to external events, and so is

not frozen.

The afterCancel cancels the

repeat event. The end result is that the images

shown previously in Figure 37-1

are hidden, one at a time, once a second, from right to left. Figure 37-2 shows what the window looks like after all

the neko images have been moved off to the

side.

Note the neko icon, sitting in the upper left

corner, hiding most of the other images. The snoozing Neko has

subsequently been unhidden and animated for your viewing pleasure. So,

how do we make Neko scamper across the canvas? This code snippet does

just that:

# Move neko right to left by exposing successive

# frames for 0.1 second.

my $cb = sub {$done++};

my ($i, $k) = (0, -1);

$delay = 100;

for ($i = 460; $i >= 40; $i -= $DELTA_X) {

$id = $IDS[++$k % 2];

move_frame($id, $i, $SCAMPER_Y);

if ($BLOCK) { $MW->after($delay) }

else {

$MW->after($delay => $cb);

$MW->waitVariable($done);

}

hide_frame $id;

}

snooze;Take one last look at Figure 37-1 and note the two leftmost

images. Essentially, all we need to do is periodically display those

images, one after another, at slightly different positions on the

canvas. The scampering code shown above does just that: move one image

from underneath the neko icon, wait for 0.1 second,

hide it, unhide the second image and display it slightly to the left

of the previous, wait for 0.1 second, and repeat until Neko reaches

the left edge of the canvas. The exhausted Neko then takes a

well-deserved nap.

It’s possible to animate Neko using a blocking or non-blocking

technique, depending on the state of the Block? checkbutton. Try each

alternative and note how the buttons respond as you pass the cursor

over them. $DELTA_X controls how “fast” Neko runs,

and is tied to the slender scale widget to the right of the window.

Varying its value by moving the slider makes Neko either moonwalk or

travel at relativistic speeds!

Before we move on, here is how neko images

are actually translated (moved) across the canvas (or “hidden” and

“unhidden”):

# Move a neko frame to an absolute canvas position.

sub move_frame {

my($id, $absx, $absy) = @_;

my ($x, $y) = $C->coords($id);

$C->move($id, $absx-$x, $absy-$y);

$MW->idletasks;

}The canvas move method moves an item to a new

position on the canvas relative to its current

position. Here we don’t even know the absolute

coordinates, so we use coords to get Neko’s current

position and perform a subtraction to determine the X and Y

differences needed. When a neko image is hidden

it’s simply moved to the “hide” coordinates occupied by the Neko icon.

The idletasks statement flushes the idle events queue, ensuring that the display is updated

immediately.

I/O Events

If you think about it, a Tk application is somewhat analogous to a multi-tasking operating system: event callbacks must be mutually cooperative and only execute for a reasonable amount of time before relinquishing control to other handlers; otherwise, the application might freeze. This is an important consideration if your Tk application performs terminal, pipe, or socket I/O, since these operations might very well block, taking control away from the user.

Suppose you want to write a small program where you can interactively enter Perl/Tk commands, perhaps to prototype small code snippets of a larger application. The code might look like this:

use Tk;

while (<>) {

eval $_;

}When prompted for input you could then enter commands like this:

my $MW = MainWindow->new; my $b = $MW->Button(-text => 'Hello world!')->pack;

However, this doesn’t display the button as you might expect. No

MainLoop statement has been executed, so no events

are processed. Therefore the display isn’t updated, and users won’t be

able to see the new button.

Realizing what’s happening, you then enter a

MainLoop statement, and lo and behold, something

appears! But now you’re stuck, because MainLoop

never returns until the main window is destroyed,[9] so once again you’re blocked and prevented from entering

new Tk commands!

One solution is to rewrite your Perl/Tk shell using

fileevent, the I/O event handler:

$MW->fileevent('STDIN', 'readable' => &user_input);

MainLoop;

sub user_input { # Called when input is available on STDIN.

$_ = <>;

eval $_;

}The key difference is that the read from

STDIN is now a non-blocking event, which is invoked

by MainLoop whenever input data is

available.

The fileevent command expects three

arguments: a file handle, an I/O operation

(readable or writable), and a

callback to be invoked when the designated file handle is ready for

input or output.

Although not necessary here, it’s good practice to delete all file event handlers, in the same spirit as closing files and canceling timer events:

$MW->fileevent('STDIN', 'readable' => ''),The entire ptksh1 program is on this book’s

web site. Another program, tktail, demonstrating a

pipe I/O event handler, is available from the Perl/Tk FAQ.

Idle Events

The idle event queue isn’t restricted to redisplaying. You

can use it for low priority callbacks of your own. This silly example

uses afterIdle to ring the bell after 5

seconds:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

#

# Demonstrate use of afterIdle() to queue a

# low priority callback.

require 5.002;

use Tk;

use strict;

my $MW = MainWindow->new;

$MW->Button( -text => 'afterIdle',

-command => &queue_afterIdle)->pack;

MainLoop;

sub queue_afterIdle {

$MW->afterIdle(sub {$MW->bell});

print "afterIdle event queued, block for 5 seconds...

";

$MW->after(5000);

print "5 seconds have passed; call idletasks() to activate the handler.

";

$MW->idletasks;

print "The bell should have sounded ...

";

$MW->destroy;

}To recap, we are responsible for three event-related activities:

registering events, creating event handlers, and

dispatching events. Until now

MainLoop has dispatched events for us, running in

an endless loop, handing off events to handlers as they arise, and

putting the application to sleep if no events are pending. When the

application’s last main window is destroyed,

MainLoop returns and the program terminates.

Perl/Tk allows low-level access to Tk events via

DoOneEvent. This event dispatcher is passed a

single argument: a bit pattern describing which events to process. As

you might guess, the event categories are those we’ve just explored.

Direct access to the DoOneEvent bit patterns is via

a use Tk qw/:eventtypes/ statement, here are the

symbol names:

DONT_WAIT WINDOW_EVENTS FILE_EVENTS TIMER_EVENTS IDLE_EVENTS ALL_EVENTS = WINDOW_EVENTS | FILE_EVENTS | TIMER_EVENTS | IDLE_EVENTS;

These symbols can be inclusively OR’d to fine-tune the list of events we want to respond too.

As it turns out, MainLoop is implemented

using DoOneEvent, similar to this meta-code:

MainLoop {

while (NumMainWindows > 0) {

DoOneEvent(ALL_EVENTS)

}

}When passed ALL_EVENTS, DoOneEvent processes

events as they arise and puts the application to sleep when no further

events are outstanding. DoOneEvent first looks for

an X or I/O event and, if found, calls the handler and returns. If

there is no X or I/O event, it looks for a single timer event, invokes

the callback, and returns. If no X, I/O, or timer event is ready, all

pending idle callbacks are executed. In all cases

DoOneEvent returns 1.

When passed DONT_WAIT, the

DoOneEvent function works as above, except that if

there are no events to process, it returns immediately with a value of

0, indicating it didn’t find any work to do.

With this new knowledge, here is another implementation of our

Perl/Tk shell that doesn’t need fileevent:

#!/usr/bin/perl -w

#

# ptksh2 - another Perl/Tk shell using DoOneEvent()

# rather than fileevent().

require 5.002;

use Tk;

use Tk qw/:eventtypes/;

use strict;

my $MW = MainWindow->new;

$MW->title('ptksh2'),

$MW->iconname('ptksh2'),

while (1) {

while (1) {

last unless DoOneEvent(DONT_WAIT);

}

print "ptksh> ";

{ no strict; eval <>; }

print $@ if $@;

}The outer while loop accepts terminal input, and the inner while loop cycles as long as Tk events arise as a result of that input.

Pong

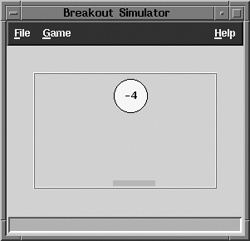

I confess. This implementation of pong isn’t

the real thing. You won’t see multiple game levels of ever increasing

difficulty or even a database of high scores. All you get is the basic

paddle and ball shown in Figure 37-3, and the

chance to bounce the ball around until you grow bored, which took less

than a minute for me.

The idea in this game is to keep the ball confined within the

playing field; you get a point every time you hit the ball with the

paddle, but lose a point every time the ball hits the floor or

ceiling. This means that the paddle is tied to your mouse and follows

its every motion. If at game’s end the score is positive you win, else

you lose. pong is derived in large part from

bounce, the widget bouncing ball simulation written

by Gurusamy Sarathy.

Of course pong isn’t meant to be fun, but to

showcase Perl/Tk features: events, canvas commands, and the Pong

derived widget.

pong really wants to be a CPU resource hog in

order to keep the ball and paddle lively, but at the same time it

needs to allow Tk events safe passage, so it has its own version of

MainLoop:

while (1) {

exit if $QUIT;

DoOneEvent($RUNNING ? DONT_WAIT : ALL_EVENTS);

$pong->move_balls($SPEED->get / 100.0) if $RUNNING;

}The variable $RUNNING is a boolean indicating

whether the game is in progress or has been paused. If the game has

been paused ($RUNNING = 0),

DoOneEvent is called with

ALL_EVENTS, and sleeps until Tk events arise, but

the ball and paddle aren’t moved. Otherwise,

DoOneEvent is called with

DONT_WAIT, which may process one or more events

(but certainly won’t block), and then the game’s ball and paddle are

moved.

If this is the entire pong MainLoop,

obviously the $PONG widget must be handling a lot

behind the scenes. Indeed, the heart of the game is this single

widget, which maintains the entire game state: paddle and ball

position and movement, and game score. $PONG is a

widget derived from a canvas, meaning that it

automatically assumes all methods inherent in a canvas (and may

provide more of its own, like move_balls).

A properly defined derived widget like Pong follows standard Perl/Tk conventions:

$PONG = $drawarea->Pong(-relief => 'ridge',

-height => 400,

-width => 600,

-bd => 2,

-balls => [{-color => 'yellow',

-size => 40,

-position => [90, 250]}]);This command creates a 400x600 pixel

canvas, with one paddle and one ball, and is

placed at canvas coordinates (90,250). Because the Pong widget ISA canvas, anything you

can do with a canvas you can do with a Pong widget. Defining a derived widget class is similar

to defining a composite class (like Odometer from last issue).

package Tk::Pong;

require 5.002;

use Tk::Canvas;

use base qw/Tk::Derived Tk::Canvas/;

Tk::Widget->Construct('Pong'),

sub Populate { # the Pong constructor

my ($dw, $args) = @_;

$dw->SUPER::Populate($args);

$dw->ConfigSpecs( ... ); # Create needed canvas items here.

return $dw;

}

1;These statements:

Define the new Tk::Pong class.

Import canvas definitions and methods.

Declare the

@ISAlist, which specifies how Perl looks up object methods. One difference between a derived widget and a composite widget is inclusion of Tk::Derived, first, in the@ISAlist.Create the Pong class constructor.

Provide a

Populatemethod (the class constructor) that customizes the canvas whenever a Pong widget is created,

pong’s Populate procedure

is really quite simple because it relies on existing canvas methods to

create the game interface. This code automatically creates the paddle

and one or more balls:

my $paddle = $dw->createRectangle(@paddle_shape, -fill => 'orange', -outline => 'orange'), $dw->{paddle_ID} = $paddle; $dw->CanvasBind('<Motion>' => &move_paddle); $dw->ConfigSpecs( -balls => ['METHOD', undef, undef, [{ }]], -cursor => ['SELF', undef, undef, ['images/canv_cur.xbm', 'images/canv_cur.mask', ($dw->configure(-background))[4], 'orange']]);

The createRectangle statement makes an orange

paddle, whose shape is defined by the canvas coordinates of diagonally

opposed rectangle corners. The paddle’s canvas ID is saved in the

object as an instance variable so that move_paddle

can move the paddle around the canvas—this private class method is

bound to pointer motion events.

Once again, in general, Populate should not

directly configure its widget. That’s why there’s no code to create

the ball. Instead, ConfigSpecs is used to define

the widget’s valid configuration options (-balls is

one) and how to handle them. When Populate returns,

Perl/Tk then examines the configuration specifications and

auto-configures the derived widget.

A call to ConfigSpecs consists of a series of

keyword =>

value pairs, where the widget’s keyword value is a

list of four items: a string specifying exactly how to configure the

keyword, its name in the X resource database, its class name, and its

default value.

We’ve seen the ConfigSpecs

METHOD option before: when Perl/Tk sees a

-balls attribute, it invokes a method of the same

name, minus the dash: balls. And if you examine the

source code on this book’s web page, you’ll see that all the

balls subroutine really does is execute a

$PONG->createOval command.

The -cursor option to

ConfigSpecs option is moderately interesting. The

SELF means that the cursor change applies to the

derived widget itself. But why do we want to change the canvas’

cursor? Well, just waggle your mouse around and watch the cursor

closely. Sometimes it’s shaped like an arrow, and sometimes an

underscore, rectangle, I-beam, or X. But in a Pong game, when you move the mouse you only want to see

the paddle move, not the paddle and a tag-along cursor. So

pong defines a cursor consisting of a single orange

pixel and associates it with the Pong widget, neatly camouflaging the

cursor.

Like neko, the Pong widget uses the canvas

move method to move the paddle around, but is

driven by X motion events rather than timer events. An X motion event

invokes move_paddle:

sub move_paddle {

my ($canvas) = @_;

my $e = $canvas->XEvent;

my ($x, $y) = ($e->x, $e->y);

$canvas->move($canvas->{paddle_ID},

$x - $canvas->{last_paddle_x},

$y - $canvas->{last_paddle_y});

$canvas->{last_paddle_x}, $canvas->{last_paddle_y}) = ($x, $y);

}This subroutine extracts the cursor’s current position from the

X event structure, executes move using instance

data from the Pong widget, and saves the paddle’s position for next

time.

That takes care of paddle motion, but ball motion we handle

ourselves, via the class method move_balls, which

has its own DoOneEvent mini MainLoop. Ball movement

boils down to yet another call to the move canvas

method, with extra behaviors such as checking for collisions with

walls or the paddle. Here’s the code:

# Move all the balls one "tick." We call DoOneEvent() in case there are

# many balls; with only one it's not strictly necessary.

sub move_balls {

my ($canvas, $speed) = @_;

my $ball;

foreach $ball (@{$canvas->{balls}}) {

$canvas->move_one_ball($ball, $speed);

# be kind and process XEvents as they arise

DoOneEvent(DONT_WAIT);

}

}Although the details of reflecting a ball and detecting

collisions are interesting, they’re not relevant to our discussion, so

feel free to examine move_one_ball yourself.

Miscellaneous Event Commands

There are three other event commands that merit a little more

explanation: update, waitWindow, and

waitVisibility.

The update method is useful for CPU-intensive

programs in which you still want the application to respond to user

interactions. If you occasionally call update, all

pending Tk events will be processed and all windows updated.

The waitWindow method waits for a widget,

supplied as its argument, to be destroyed. For instance, you might use

this command to wait for a user to finish interacting with a dialog

box before using the result of that interaction. However, doing this

requires creating and destroying the dialog each time. If you’re

concerned about efficiency, try withdrawing the

window instead. Then use waitVisibility to wait for

a change in the dialog’s visibility state.

We’ve now covered most everything you need to know about event handling in Perl/Tk. In the next article, we’ll explore how to lay out widgets on the screen with the grid geometry manager.

[9] You can have more than one main window, so strictly speaking this should be “until all the main windows have been destroyed.”