Recruiting research participants is notoriously frustrating and easy to mess up. If you do mess it up, you risk blowing the validity of the study, and even if you don’t mess it up, it can still be a big drain on time and money. Many researchers are glad to hand over recruiting to a professional third-party recruiting agency, paying anywhere from $100 to $800 per recruit (depending on the stringency of the recruiting criteria). Others rely on in-house email lists, academic volunteer pools, paid participant panels, or personal contacts, each of which may not provide a representative or unbiased sample, for a number of reasons. And worst of all are online classified ads like those on craigslist, where the recruits are usually biased or, at best, solely interested (as opposed to mostly interested) in collecting an incentive check.

But then there’s the rest of the Web: a huge pool of anonymous, disinterested, ordinary people who wouldn’t necessarily consider participating in a research study, much less join a panel of standby participants—in other words, very promising research participants. This section will teach you how to recruit those people, confirm that they’re qualified, contact them, and convince them to take 40 minutes out of their day to participate in a research study, all in a reliable, ethical, and nonirritating way.

Note that you can use these methods to recruit for any kind of study, whether moderated or automated, in-person or remote, live or scheduled. And we’ll also explain why doing it this way is worthwhile.

Live recruiting is using your Web site to collect voluntarily submitted user info and then using that info to contact qualified users within seconds. Why would you want to do that? First, it eliminates the need to schedule users in advance. Since you’re using remote methods, you can begin a study at the very moment the recruit agrees to participate. And by intercepting visitors to your Web site using a form or pop-up window, you can instantly screen and call them within minutes of their submitting the form— that’s what makes it “live.”

Predictably, live recruiting has its advantages and limitations. The biggest advantage, which is an advantage of remote research in general, is that it enables time-aware research.

Note

LIVE RECRUITING IS THE KEY TO TIME-AWARE RESEARCH

Remember that “time-aware research” concept we keep bringing up? Live recruiting is the easiest way to make it happen. By recruiting participants just as they’re about to perform a task you’re interested in watching, you can contact them and begin a remote research session right away. We can’t overemphasize how much of a difference this makes.

Let’s say you want to study people who are browsing for laptops on your Web site. If you’re live recruiting, you can wait until you hear from people who say, “I’m browsing for laptops,” and then call them right away, so you can actually watch them browse for laptops on their own initiative. You don’t have to tell them to pretend that they’re browsing for a laptop. Users with real motivations for their tasks provide you with insights into how people actually use your product or Web site, which you can use to make your designs easier, better, more useful, and inspired by real behavior.

Another benefit to live recruiting is that it can ease the problem of participant flakiness. Tardiness and no-shows are a constant pain in prescheduled research studies because users can be late for a million reasons: couldn’t find the lab, got stuck in traffic, just plain forgot, and so on. For every four to eight users who are scheduled, most recruiters arrange for at least one backup user, who must still be paid the full incentive amount. This problem disappears when you recruit live because the sessions aren’t prescheduled.

Instead, with live recruiting what you need to worry about is having a constant stream of users responding to your recruiting screener. Many factors feed into this (discussed in the following section), but if your circumstances favor a high response rate, live recruiting has the potential to make recruiting cheaper and more reliable (see Table 3-1).

Table 3-1. Comparing Recruiting Methods ![]() http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4287138454/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosenfeldmedia/4287138454/

Agency | Email/Personal Contacts | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Cost | Cost of developing the screener or using a Web sendee (usually cheap) | Typically, $150–$600, depending on allotted time and criteria strictness | Free, but can be time consuming |

Validity | Depends on screening ability of researcher | Depends on screening ability of recruiting agency, in cooperation with researcher | Low |

Reliability | Depends on Web traffic; high, with 1,000+ unique visits per hour | High, but requires backups in case of no-shows | Low, depends on size of contact list; gets harder with subsequent studies |

Time | Fast with 1,000+ unique visits per hour; not viable with fewer than 500 daily visits | 1–4 weeks | Depends on size of available contacts |

Effort | Medium; researcher bears responsibility for proper screening, participant data management | Low; researcher drafts requirements document | Medium; researcher bears responsibility for proper screening |

Requirements | Healthy Web traffic, administrative/editorial access to a Web site | Enough money, a recruiting agency that covers local parricipants | An existing list of contacts you have permission to contact |

Live recruiting also incorporates much of the recruiting phase into the testing phase, shortening the overall project schedule. Old-school recruiting methods require two to four weeks of contacting prospective users, screening and vetting them for their qualifications, briefing them on the study preliminaries, and sending reminders. And then once people start showing up, you’re stuck with what you get. When you recruit live, the bulk of the screening is done through the Web form or within the first few minutes of calling a participant. This usually means you’ll have to contact a few respondents before you can find one that’s qualified, willing, and available to participate. The average time per session goes up, but if you have enough respondents, this approach is faster than advance screening.

Note

CAN I RECRUIT FIRST-TIMERS?

Many of our clients want to know if it’s possible to live recruit users who’ve never seen or had any experience with the product or Web site; the answer is yes. To do so, you need to have a screener question that determines whether or not the respondent has had any experience, and then you need to contact the respondent to begin the session immediately after receiving his or her response. Usually, you can catch the visitor within a minute of entering the site for the first time, which is fine for a “first-time visitor” for most purposes.

If you need a 100% new visitor, however, the best approach is to place the recruiting screener on a different Web site and then direct the recruit to the interface you want him/her to test. You may find, however, that you get a lower proportion of qualified recruits this way.

Finally, when you recruit from the Web, you’re the one in charge, rather than a third-party agency, and your participants (except fakers, who are discussed later) will come from a single source—visitors to your Web site. This gives you more control and greater transparency over your participants, which can help boost the validity of the study. The recruiting sources of recruiting agencies aren’t always clear, and often include personal contacts, standby participant panels (i.e., professional participants, often used in market research), and in some cases, even shady email lists. That doesn’t necessarily translate into bad participants, provided the agency does its job right. With live recruiting, there’s more transparency to the source of your recruits, and they’re usually people who are coming to your site because they’re genuinely interested in your products, services, software, cute puppy videos, or whatever.

Note

REMOTE TESTING VS. REMOTE RECRUITING

Live recruiting is great for gathering participants for remote research studies; however, you don’t have to use live recruiting for a remote research study, nor do you have to use traditional recruiting methods (agencies, email lists, panelists, friends, and family) for lab research. Remote testing and remote recruiting are separate. You can mix and match approaches to your testing and recruiting: use remote research tests with prescheduled participants or recruit people from your Web site for in-person lab tests.

There’s lots of room to innovate with live recruiting. The one strict requirement is that you have administrative/editorial access to a Web site with a decent amount of traffic. (If not enough people visit your site, or you’re still in super-secret startup mode and don’t have a live Web site, you may be hosed and are probably better off going with a traditional recruiting method.)

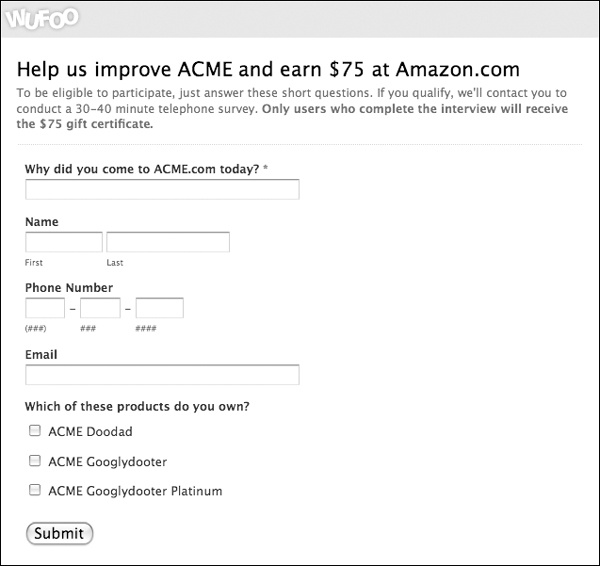

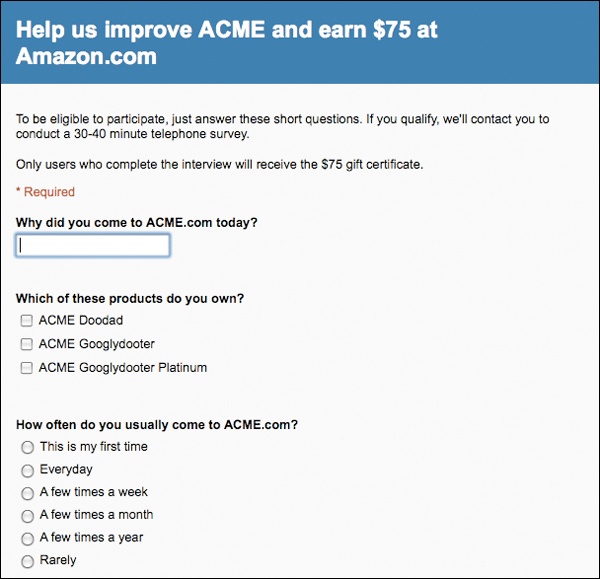

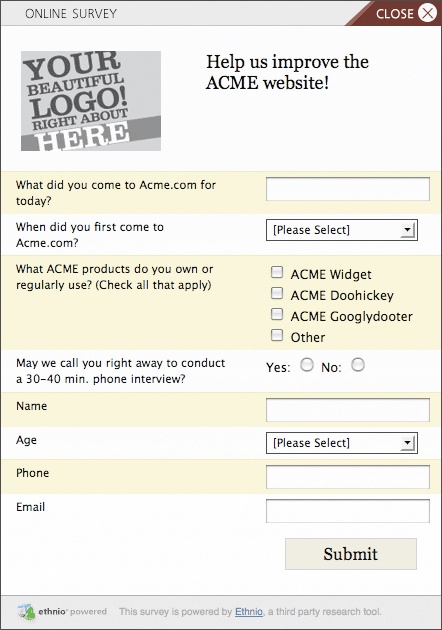

The most straightforward option is to create a separate standalone page containing the recruiting screener form, which users can fill out to opt-in to your study. It’s easiest to make by using an HTML form-building tool like the excellent Wufoo or Google Docs’ form functionality (see Figure 3-1 and Figure 3-2). You can then link to the standalone page from one of your main pages. Alternatively, if you’re able to just embed the form somewhere on an existing page, users might be more likely to fill it out. Some remote research tools and Web services[3] like UserZoom and WebEffective offer JavaScript-based intercept forms as part of their comprehensive user research services but require you to sign up for the whole enchilada.

Figure 3-1. A sample HTML recruiting form using Wufoo. You can embed this somewhere on your Web site, or you can link to it as a standalone page.

Figure 3-2. A sample HTML recruiting form using a Google Docs form, which is also linkable and embeddable.

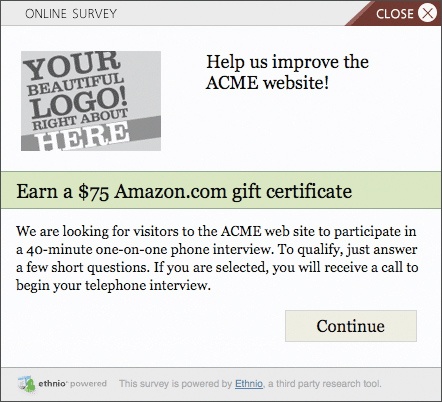

Contact forms are fairly easy for Web site visitors to overlook. One thing we’ve learned in our years of UX research is that most visitors often ignore elements on a Web page that don’t appear to help them achieve what they came to do. A more effective strategy is to use a popup form. While it may be a minor distraction to some of your site’s visitors, it is the most reliable way to recruit legitimate visitors to your site for your study, and there are many ways to minimize unnecessary screener display. The most common problem with pop-ups is that most Web browsers nowadays come with popup blockers, which prevent your users from even seeing the screener. The solution is to display the pop-up not as a separate browser window, but as a DHTML layer, which is what many pop-up Web ads are.

To get the code for these recruiting forms and pop-ups onto your site, you may have to jump a few logistical hurdles. If you’re in charge of running and maintaining your site, or you work for a small company, you’ll need to determine where on the page you want or need to put it. (Ethnio, which we describe later, requires only a single line of JavaScript below the closing HTML body tag. If you don’t know in broad terms what JavaScript and a body tag are all about, please tell @boltron on Twitter, and he will gladly recommend some other books for you.)

In larger organizations with more layers of content management protocol and IT bureaucracy, you’ll have to arrange things carefully in advance with those who are in charge of maintaining the code. IT operations guys tend to hate external code and will want to know things like what does the code do? Is it secure? What pages does it need to go on? Will it work with our (complicated, Orwellian) CMS? If the IT folks are going to be in charge of implementing the recruiting code, you need to make clear to them exactly what the screener questions should say and how they should appear. In some organizations, changes to the Web site can be made only at certain times of the day or week, so you may need to schedule your study around that.

Higher-ups who are in charge of managing the Web site as a whole will want to know which pages the screener will appear on, as well as how long the recruiting code will be active, what the screener will look like, how many people will be seeing it, if there’s a way they can shut it off or disable it on their end, and whether or not the look and feel of the screener will match that of the Web site.

The answers to these questions will vary depending on which recruiting method you’re using. For hand-coded forms and pop-ups, you’ll need to consult with the people who are implementing the code. If you’re using a service like Ethnio, Google Docs’ forms feature, or Wufoo, check the FAQs and Help documentation on the respective service’s Web site.

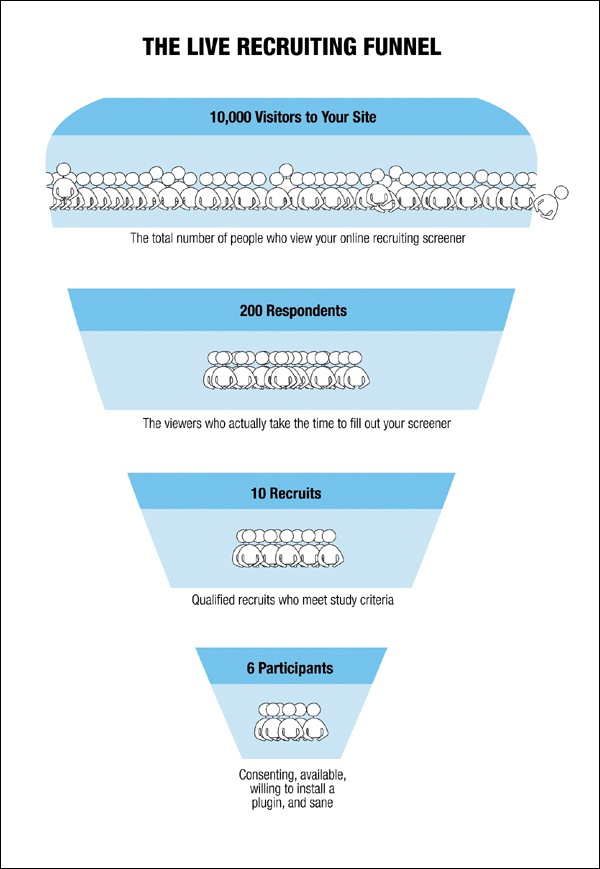

There’s a rough formula we follow to predict the recruiting rate for a standard pop-up screener: between 1.5 and 2% of visitors who see the screener will fill it out, and a little over half of those will usually consent to being called. Once you start calling people, usually about 65% of the people you call will be able to successfully participate, depending on your target audience.

If you want to have a steady stream of recruits so you can reliably intercept people right as they come to the site without having to wait long, you’ll need at least six qualified, willing recruits per hour, which would require site traffic somewhere north of 1,000 visits an hour during testing hours (see Figure 3-3). In most cases, we find that people with 10,000 daily unique visitors or more do just fine with live recruiting.

You can manage with fewer if you’ve given yourself plenty of time for testing, but be warned that there may be long periods of time when you’re waiting idly for a new and qualified recruit to come in. (Observers should definitely be made aware of this fact ahead of time.)

The most important step in the Web recruiting process is designing the recruiting screener: the form that Web site visitors will use to submit their recruiting info to participate in the study. A good screener will bring you a steady stream of recruits from which you can choose a representative sample of your target audience.

There are three components to the screener to consider: the introduction, questions, and confirmation.

Make the incentive and purpose of the screener immediately clear. Stick with a straightforward, high-visibility header, followed by a very short description:

Help us improve our Web site and earn $75 on Amazon.com

We are looking for visitors to the ACME Web site to participate in a 40-minute one-on-one phone interview about the Web site. To qualify, simply answer these few short questions. If you are selected to participate, you will receive a phone call shortly.

Visitors can easily mistake the screener for a pop-up ad or a sleazy sweepstakes offer, so you’ll want to make clear that it’s legitimate. A clean design and the Web site’s logo (if applicable) can help put people at ease. (This is the biggest visual design challenge—not seeming like an ad.) You also should be clear about how the user will benefit, without making it sound like a promotion or a sweepstakes—no exclamation points, no “You could win X dollars!” Friendly is okay, but you want to avoid sounding gimmicky or excessively jokey.

After the description, either provide a clear link to the screener questions or introduce the questions directly below.

Screener questions should be unbiased, comprehensive, noninvasive, and strictly relevant to the recruiting goals.

There’s only one question you absolutely must ask in all cases, which is the “consent to contact” question: “May we contact you right away to conduct the 40-minute phone interview?” For moderated studies, you’ll also want to ask for a phone number to contact the user to begin the session. Aside from these, you should include only questions that are useful for determining whether the respondent is qualified to participate in the study, so keep the question count low. Use as few questions as possible, and no more than 10. Participants tend to abandon long screeners, considering that they may not even get anything for filling it out. The questions should map directly back to the recruiting criteria you defined in the planning stages of the study.

Note

USE DROP-DOWNS EFFECTIVELY

To help cut down on the number of questions you’re using, you can often use drop-down menus to address more than one qualification at once. In a study we conducted for Wikipedia, we asked the following: “Have you ever contributed to Wikipedia?” [Yes, started a new article / Yes, edited an entry / Yes, made more than 50 contributions / No, never]. From the response to this question, we were able to determine not only whether respondents had edited entries in the past, but in what way. A cleverly designed drop-down question can answer three or four questions at once, without being too cumbersome.

We like to begin with a simple open-ended question: “Why did you come to the site today?” This question not only helps determine whether a user’s motives for coming to the site match the goals of the study, but also helps to root out fakers (an issue we’ll go into later). After that, your screener will probably consist of three to five short questions that will help you place respondents in a recruiting category; these questions vary depending on the goals and target audience of your study. When drafting closed-ended questions, make sure that the choices are exhaustive and that each choice unambiguously qualifies or excludes participants based on a particular criterion. For example, if you’re selecting participants from a certain age range, be sure all the ages are covered—e.g., “[Under 18 / 18–35 / 36–55 / Over 55]”. We advise against relying on too many survey-type questions like Likert scales and exhaustive check box fields for recruiting purposes because respondents generally tend to get bored and rush through them.

If you can, require users to fill out all fields before submitting the form. Disabling the submit button until all fields are filled is a good way to do this.

Note

COMMON QUALIFYING SCREENER QUESTIONS

For most studies, there are a number of pieces of information about users that are nice to know and that can be collected very easily. Age, phone number, email address, gender, location (city/state, not address), size of company, and occupation are sometimes good to know, depending on what kind of interface you’re testing. Other common questions include

“When did you become a member of ACME.Com?”

“When did you first visit ACME.com?”

“How often do you come to ACME.com?”

“Which ACME products do you own (check all that apply)?”

“How did you find out about ACME.com?”

Remember, you’re trying to keep the screener short and focused only on the information that’s important for determining participant eligibility. So if you’re not using the information to decide whether the user is qualified to participate, ask it as a warm-up question during the actual study session instead. Also, while it’s true that you can often implicitly infer things like gender or location, don’t rely on that inference if knowing that information is important. Just ask.

And now some ethical considerations: you have to assume that some people responding to the screener probably have no idea what will be done with the information they’ve submitted, so don’t abuse that information. On top of the researcher’s responsibility to keep basic personal information (names, email addresses, location, etc.) private and secure, you shouldn’t request sensitive information: Social Security number, credit card number, passwords, any of that. Recruiting records should be stored, erased, or anonymized in a secure and responsible way. While seeing the users’ recruiting info may be useful and helpful, you obviously don’t want to face the repercussions if that information gets leaked somehow. This goes double when minors are involved: there are oodles of legal and ethical considerations. You want to make sure that users under age 13 are either restricted from submitting screener responses or that you otherwise follow the appropriate legal protocol in your area. These important consent and privacy issues related to gathering user info are covered in the next chapter. (Also, believe it or not, we belong to the market research [gasp!] association ESOMAR, which publishes strict guidelines for privacy around information gathered in consumer research. You can find these guidelines at www.esomar.org/index.php/professional-standards-codes-and-guidelines-mutual-rights.html.)

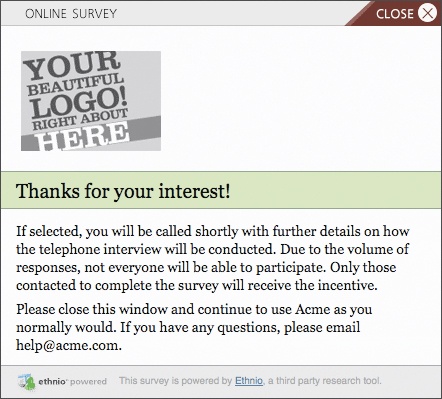

Respondents often get confused about the screener; some mistakenly think that the screener is the study and will occasionally fill your inbox with hostile questions about why they haven’t received their $75 gift certificate. So make it clear here that the screener is only to determine eligibility for the study and that only people who complete the interview will receive the incentive:

Thank you for your interest! If selected, you will be contacted via telephone within a day with further details on how the telephone interview will be conducted. Due to the volume of responses, not everyone will be able to participate. Only those contacted to complete the interview will receive the incentive.

Note

ALWAYS TEST YOUR SCREENER! ALWAYS!

At least a day before the testing sessions begin, run a test of the recruiting screener. Place the screener on the site exactly as you would if you were actually recruiting, and if possible, get a few people outside your network to fill out the screener using different operating systems and browsers to see whether it’s displaying and storing responses properly.

The screener test is crucial for catching any technical glitches ahead of time, as well as for giving you a sense of the volume of responses you can expect to receive during the actual research sessions. If the volume is low, you’ll probably need to tweak the screener design (see the “Recruiting Slow?” section later in this chapter).

As with any form of user research, you’ll probably need to offer an incentive (aka “honorarium”) to users to entice them to participate in your study. Unlike in a prerecruited in-person study, however, in a remote research study you won’t be able to physically hand a check, gift certificate, or money voucher to your participant after the session is finished, and some people are understandably reluctant to give out their mailing address to a random Internet person who just called them.

For those reasons, we like to offer Amazon.com gift certificates. All you need to be able to send them is the recipient’s email address, and we’ve found them just as effective as cash for purposes of attracting participants. However, if you have something equally appealing to offer that doesn’t require users to give out more personally identifying information—discount codes for your company’s merchandise, etc.— go for it. If you encounter legal or ethical issues when giving out incentives (some company accountants get skittish about doling out incentives to strangers), you can even offer to donate to a charity in their name.

The amount you should offer to the participants depends heavily on whom you’re looking to recruit. The average participation incentive for a typical remote study is somewhere between $50 and $75, which is lower than most in-person studies, since you don’t have to incentivize users to travel to a testing location. If you’re testing busy high-income professionals (doctors, lawyers, businessmen), you’ll need to hike up the amount. We’ve had to offer as much as $300 to reliably recruit doctors and business executives for a 30–40 minute session. (Be careful: the higher the incentive, the greater the risk of “fake” users. See Choosing Good Users and Spotting the Fakers for tips.) On the other hand, you’d be surprised at the number of people who are willing to donate their time for no incentive at all; this is often the case for Web sites with a dedicated community or fan base, or for sites with so much traffic that there’s bound to be a few philanthropists in the mix.

Incentives are trickier to handle when testing internationally. Amazon or Amazon-like online vendor gift certificates are still your best bet in most industrialized nations. PayPal can work too. In the developing world, wire transfer of cash might be your next-best bet. Typically, incentives are modest enough that you don’t have to worry about running into legal troubles transferring money overseas, but using this type of incentive does mean that you’ll have to gather additional information from each participant after each session. The information varies depending on what kind of service you’re using, but for most transfers you’ll need to determine what the nearest wire transfer location is (e.g., Western Union, American Express), the full name of the person you’re wiring the money to, and the city and country where the money will be received. Just make sure that you get all the information you need to fulfill the incentive.

A few notes on recruiting people from the Internet: the world is what it is. Some people will want to join the study because they have a bone to pick with your company and won’t cooperate with anything you ask them to do. Others are professional survey-takers; their responses are slick, canned, and a little suck-uppy. (“This site really helps me achieve my goals, and the quality of the design shows me that this is a company that really cares about its users.”) And yet others will try to take advantage of your generous offer by fibbing on the screener form to look like an ideal study participant; usually, these “fakers” are terrible participants because they’ll be unengaged (“Yeah, it’s a good Web site. It’s fine. I don’t have a problem with it.”), or they’ll try to say what they think you want to hear—the infamous “Hawthorne effect.” These people will not give you good feedback.

The ideal way to deal with these problem recruits is to screen them out from your recruiting responses before you even talk to them. Suspicious patterns and similarities in user details may signal that someone is telling friends about the study. Check the email address domains for groups of uncommon email domains (e.g., @harvard.edu, @dell.com), which may signal that word about your study has gotten out around a particular institution. Since you have the participant’s contact phone number, you’ll also be able to check for recurring area codes, which often correspond to location. Unless it’s important to talk to users from a particular region, it’s nice to get a mix of area codes to ease the likelihood that you’re talking to a bunch of buddies. This likelihood is even greater if those similar responses are received near one another in time. It could be a coincidence, but be wary.

Another antifaker strategy is to ask at least one open-ended question in your screener and your introductory questions. Most authentic visitors to your site will have a good specific reason for being there, and by asking open-ended questions, you can usually get a strong intuitive feel for authentic visitors. We almost always begin our screeners with the simple question “Why did you come to [Web site name] today?” If the answer is suspiciously vague (“for info,” “just looking around,” “to see the offerings”), you should be careful to screen the user further if you choose to contact him/her. If the answer is straightforward and specific and fits the study goals nicely (“I came to compare prices between the iDongle and the iDongle Pro”), you can probably be more confident.

On the Internet, info about deals and bargains gets out fast. When your incentive is particularly lucrative or your screener is visible to a lot of people, there’s going to be a greater risk of fakers. Be prepared for the possibility that someone is going to see the screener and post about it on some community bargain-hunting or “free stuff” Web site (FatWallet.com, ProBargainHunter.com, Jangle.com, any random message board...). What do you do? Be sneaky and ask questions that trick the fakers into tipping their hand. We like this multiple-choice question: “What’s your favorite bargain-hunting Web site?” [Fatwallet, ProBargainHunter, Other, No idea what you’re talking about]. If the user selects anything other than the last choice, you’ll either want to pass over that recruit or do some extra vetting at the beginning of the session.

Inevitably, however, a few problem users will slip under your radar—see Chapter 5 for tips on how to deal with them.

Note

CHECK YOURSELF

The participants are not always at fault when bad participants are selected. Sometimes your own subconscious biases can get the better of your good judgment. Don’t cherry-pick users; there’s a difference between choosing users who fit the criteria and choosing users just because you think they will be “good participants.” The basic guideline to follow to ensure a fair sample when live recruiting is to simply choose the most recent qualified recruit—no picking and choosing on the basis of how good a recruit’s spelling is, for example, or just because the recruit irritatingly typed responses in all-caps. That’s not to say, however, that you shouldn’t dismiss uncooperative users. Again, if a user seems extremely reluctant to talk or appears to have some kind of bad-faith agenda, don’t hesitate to politely dismiss that person.

Getting other people who are familiar with the recruiting objectives involved in the recruiting can help mitigate your own biases. Stakeholders, as always, should be encouraged to involve themselves in the recruiting process if they’re available so that they can evaluate recruits case by case. It’s useful to have many eyes on the incoming responses so that no promising recruit gets overlooked or unfairly neglected.

A common problem: it’s testing day, and not enough people are responding to your screener for steady recruiting (about six qualified recruits per hour). Your time is valuable, so you shouldn’t wait any longer than 10 minutes before taking action to bring in more qualified recruits.

The first thing you should try, if your recruiting solution allows it, is to adjust the screener. Proofread the introductory text. Remember, you want concise, direct prose that doesn’t sound promotional. Reducing the number of questions on the screener makes it more likely that visitors will fill out the whole thing. If you’re using a screener with an adjustable display rate (i.e., it displays to only a certain percentage of visitors) and the rate is lower than 100%, increase the rate. If this adjustment can be done quickly and easily, consider increasing the display rate to 100% while waiting for a qualified recruit and then bringing it back down once you’ve got a user on the line. That way, you can get recruits coming in when you need them, and you’re not distracting the site’s visitors while you’re testing.

If you’re recruiting from a big company Web site and aren’t in charge of making the necessary edits to the page, making these small changes at will is not going to be easy, so the presession screener test well in advance of testing will be even more crucial to get a sense of whether anything needs to be adjusted.

Consider raising your participation incentive incrementally. If you’ve been offering $50, bring it up to $75 after 15 minutes of slow recruiting, then to $100 after an hour. This approach is always preferable to sitting around and waiting, unless you’ve scheduled a lot of time for testing and you can afford to sit and wait for the right participant to come in. Remember to get the approval of whoever is financing the incentives. If you raise the incentive too high, though, beware of money-seeking fake participants. See Choosing Good Users and Spotting the Fakers earlier for more details.

If you have a large Web page and you’ve placed the screener on a page somewhere deep in the navigation, consider placing it on a more prominent page, like the homepage. You’ll definitely get more responses this way. They may not all be as relevant as they were when the screener was on a more specific page, but the overall number of more qualified recruits should be higher.

If you’re getting far fewer users than you expect, check to see whether your screener is actually working the way it should. Is it displaying correctly to all users, and do their replies get through to you? You usually catch these glitches during the screener test, but technical bugs, like human feelings, are unpredictable. If you have a suspiciously low number of recruits, make sure that your screener is displaying correctly on different browsers and operating systems. Clear your browser’s cache and cookies and try reloading your page again. If you’re not tech-savvy enough to make the necessary adjustments, be sure to have an IT guy on hand to help you root out the bugs.

Before you start recruiting real users from your Web site, read through the next chapter to make sure you have all your legal privacy and consent obligations sorted out. It’s very important!

Live recruiting is a method of getting people who visit your Web site to participate in your remote research study.

Live recruiting is what makes Time-Aware Research viable, because you can catch people just as they’re about to perform a task you’re interested in observing.

The most reliable way to live recruit is by placing a form or a DHTML pop-up (the “recruiting screener”) on your Web site, using services like Wufoo, Google Docs, or Ethnio.

For larger organizations, there will be organizational obstacles for placing the recruiting screener; make sure that your IT department and upper management are on the same page as you.

You’ll probably need at least 1,000 unique site visitors per hour for viable live recruiting.

Keep your recruiting screener short and to the point: no more than 10 questions, including the obligatory consent-to-be-contacted question.

In lieu of cash, online retail gift certificates are effective, easy-to-fulfill participation incentives; the gift amount depends on how hard the participants are to find. Merchandise and even volunteer requests can also work sometimes.

Some people will try to cheat or game the recruiting screener. Scrutinize the responses carefully, especially open-ended ones, to spot fakers. Sometimes an anti-faker trick question will be necessary.

If you’re not getting enough qualified recruits in spite of decent Web traffic, proactively edit your recruiting screener and incentive ASAP, instead of wasting time waiting for the right users.

[3] We maintain a list of services on our Remote Usability Web site (http://remoteusability.com), as well as in Chapter 8 of this book.