Fashion tech is an interdisciplinary field that merges traditional fashion and textiles with modern electronics, software, and other technologies. In this book, we consider fashion tech to mean interactive garments or accessories that incorporate electronic components, or that were created using digital fabrication technologies like 3D printing. Technologies like these have only recently become available at the consumer level because of advances in the production of electronics that have lowered the cost of computers, sensors, and light-up components that can be embedded into everyday objects. This chapter introduces fashion tech and talks about how you can use this book to get started as a practitioner in this new field.

A Brief History of Fashion Tech

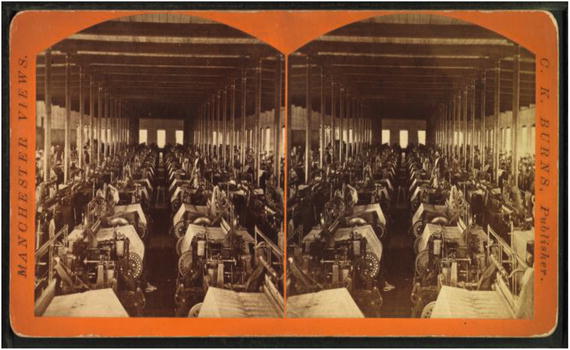

Creating clothing to protect ourselves from the weather has been an inspiration for technology development since antiquity. Tools have gone from bone awls for punching holes in leather, to spindles for creating yarn, to the looms that could produce vast amounts of fabric at industrial scale. Figure 1-1 shows an 1875 stereoscopic photograph of the Amoskeag (New Hampshire) Gingham Mill weaving room. (There is an animation of this stereo image at http://stereo.nypl.org/view/14480 ).

Figure 1-1. Weaving, circa 1875. From the New York Public Library ( http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-7c18-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 )

The desire to create elaborately patterned fabrics led to the development of the Jacquard loom in 1801. A weaver created cards with holes in them that controlled (through an ingenious system of lightly tensioned springs and wires) the patterns the loom was creating. This allowed automatic generation of very elaborate patterns such as brocades.

Fancy fabrics for drapes and wedding gowns is not the end of the story, though. English mathematician and inventor Charles Babbage saw the Jacquard loom punch cards and wondered if a similar system could be used to create a more general computing machine for mathematical problems, which he called the Analytical Engine.

Babbage first described the machine in 1837; the full machine was never actually created ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Analytical_Engine ). Nevertheless, Babbage is widely seen as the inventor of the general-purpose computer, and the descendants of its punched cards were in use well into the 1970s. And so, the computer has its birth in Victorian fashion tech!

Tip

If you are interested in the history of textile technologies, check out the amazing historical archive with many illustrations and original documents at www.cs.arizona.edu/patterns/weaving/index.html . More specifically, if you would like to download a Victorian-era book on how to create the cards for a Jacquard machine, E. A. Posselt’s The Jacquard Machine Analyzed and Explained (Posselt, 1893) is now in the public domain and available from the Hathi Trust Digital Library at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/gri.ark:/13960/t26b0d33d .

The introduction of the integrated circuit in the late 1950s and its rapid evolution have now resulted in affordable computers that are comparable in size to coins. The late Gordon Moore predicted in 1965 that the performance of computer chips would roughly double every two years based on technology improvements; Moore’s Law, as it came to be called, has been remarkably accurate (so far). This means that early-1980s supercomputers are outclassed by 2016 single-board computers that are a few inches across and cost $5.

Other digital electronics have kept pace, and tiny processors and sensors developed for smartphones, cameras, and other devices now make it possible to unobtrusively include as part of a hat or apron processing power that would have had been ministered to by dedicated staff in the 1980s. Coming full circle from the Jacquard loom, it is now possible to have circuits woven into clothing. (We talk about Google’s Project Jacquard in Chapter 13.)

Another side effect of access to cheap, easy-to-program electronics has been the rise of robotics-based consumer products, like low-cost consumer 3D printers and computerized home sewing machines. 3D printers in turn make it easy to prototype physical objects quickly and cheaply, and are leading to even more innovation. Feature-laden home sewing machines can enable complex projects that would have been too much for the hobbyist in the past.

The bottom line of all this is that you have access to a fantastic array of technologies to make cool projects. In this book we focus on using digital electronics and related technologies (such as 3D printing) in fashion applications like creating costumes and other interactive wearable pieces.

Costuming

Now that it is possible to make a more elaborate and professional-appearing costume at home, it is not surprising that cosplay—dressing up as and role-playing a favorite fictional character—has become something of a subculture, initially in Japan but rapidly spreading to the United States and elsewhere. Science fiction and other kinds of conventions often have cosplay fans attend as their favorite character. Anime and video game characters are favorite subjects. Given that, there are many opportunities where an otherworldly effect is desired, and the technologies in this book might be just the thing to take a cosplay costume to the next level.

Historical costuming has always been always popular. Renaissance Faires ( www.renfaire.com ) have popularized historical re-enactment of activities of the late Elizabethan era and dressing up as a person from that time. Visible electronics might be out of character, but there could be a dragon on your arm with glowing eyes or a head that turns toward the light.

You may be reading this book for ideas on enhanced theatrical costumes, either for school productions (as Lyn talks about later in this chapter) or for professional use. At the school level, costumes likely need to be low-budget, assembled quickly, and easy to get in and out of for a ten-year-old with stagefright. A few strategic special effects enabled by electronics can make a costume memorable. For example, Lyn and her students added programmable glowing eyes to fish for The Little Mermaid.

Finally, there are just plain dress-up costumes for parties, holidays, and so on. Figure 1-2 shows custom-made, vacuum-formed (Chapter 13) plastic armor as it looks in a box, and in Figure 1-3 it briefly transforms Sir Rich to his true knight-errant identity.

Figure 1-2. Plastic armor in its box

Figure 1-3. The armor fitted on our knight-author

Some costume elements such as masks (Figure 1-4) or a period dress can take a person to another place and time. If you have a fantasy costume anyway, why not mix it up and make it interactive? (Armor and masks courtesy of Make Believe in Santa Monica, California; we talk more about them in Chapter 2.)

Figure 1-4. Masks

Maybe you are not looking to make a costume, per se, but are looking to do something functional—a wall hanging that lights up as a night light when it gets dark, maybe, or strategic LEDs inside a bag so you can find your keys at night.

Our point in all this is that the first step in applying the technologies in this book is to think about what you are trying to do and how you want it to look. Too often people start out wanting to use a technology for its own sake, but that often does not end well. Just because it is possible to make an interactive garment or art piece, why should you?

If you are reading this book you may be planning to build costumes like those we just described. Or you may have been asked to develop a class for high school or college students. If you are a teacher or parent, fashion tech projects can be a good way to convince students who otherwise might have been scared off electronics or programming to give them a try, motivated by the final product.

Our Design Philosophy

We (Joan, Rich, and Lyn) came into this field from very different directions. Rich is a Millennial who grew up designing electronic projects (including one of the forerunners of today’s consumer 3D printers and a small, elegant 3D printer still being sold by a company Rich and Joan used to work for—you can see one in Chapter 9). He likes to make things for their own sake, the usual definition of a hacker. (In the circles we travel in, hacker does not have a negative connotation. The people who do bad things with their skills are called black-hat hackers.) Rich is very detail-oriented and has encyclopedic knowledge of the hardware and software we cover in this book.

Joan comes to this as a recovering rocket scientist, and her role is to keep the big picture in mind and think about how to avoid going into too much detail in any one technical area. She worked on spacecraft to other planets, where one tiny mistake could cause disaster. So she brings structure and experience working on complicated systems, and also the desire to make explanations as simple as possible (while still being correct).

Lyn comes with long experience making costumes for middle and high school productions. Besides the ability to apparently whip up costumes out of a pile of fabric plus thin air, she has a sense of humor and a keen eye for when a small detail might make all the difference. She has also taught sewing in a classroom and so knows what pitfalls might arise.

The three of us take turns guiding you through the book and switch into first person for much of the book when we focus on one person’s particular expertise. Sometimes we collaborate too closely for any one of us to take the lead, and there (as we do here) we will just say we.

We are walking through our backgrounds here (there is more in the “About the Authors” section at the front of the book) because we suggest that you build a team to work on your first projects that has all these aspects, though not necessarily spread across the team the way it happens to be with the three of us. Good chemistry and a sense of humor are also important for a team to have. Sometimes things just come out looking silly, and you have to laugh, figure out what went wrong, and not do that again. At other times you may need to let one of your team members go off in a corner and try things for a while. But if one of us got stuck, we found it valuable to articulate what the problem was to the others, and we could go back to first principles and try to think about what we were trying to accomplish.

Planning Your Projects

There are many books out there that cover different aspects of making a fashion tech project, and many projects on the Internet that you can try. We felt an orderly path was missing, starting with the basics of sewing, plus electronics hardware and software, to allow someone who knows very little about the skills needed to get started on projects.

We always emphasize the idea of system design. It is very easy to come up with a great idea for part of a project, but doing that part the way that you would if it was not incorporated into something wearable might be very different than the way you should start out to incorporate it into a dress or hat. We cannot emphasize enough the need to plan out a complex project end-to-end ahead of time. Chapter 10 tells the story of the first project we did together in which we largely ignored this principle—even though all three of us knew better.

In this book we cover the basics of sewing (including making and using patterns), creating electronic circuits, and programming. These are the core skills of most fashion tech projects, and we go into considerable depth on each one. We have laid the chapters out in the order you would most likely create a project: sewing first, then figuring out the circuitry, and then programming it if needed. We guide you in managing complexity in your projects and give you tips on how to avoid being overwhelmed if your project does not work.

The Wearer’s Environment

As Chapter 2 advises, you also need to think hard about what the wearer is going to be doing and what environment they will be in when they are wearing the garment. For example, the projects in this book are all intended to be worn indoors, in a dry environment. Even though one project is an apron, we imagine it as more something one would wear to impress friends while serving food at a party, and not so much when cooking or with wet hands.

Prototyping and Testing

As you plan out projects, think about where in the project development you might be able to cobble together mini-prototypes. For the sewing portion, you might make a muslin—a version of the project in a very cheap fabric that you will not mind taking stitches out of and resewing multiple times if necessary. When creating electronics, you might initially use alligator clips (clips to hold together a circuit temporarily) to create a circuit that you will ultimately sew on with conductive thread. And when programming, you should consider how to create some simple stepping-stone projects that build up the ultimate functionality one part at a time. As we go through the book, we will suggest these techniques. As you are coming up with ideas about what you want to do, consider how to make some parts of it independently testable so you are not left with a complex project that might have multiple interacting problems.

The most important thing, though, is to figure out what you want the costume to be first, and add the technology or animation second. Lyn will now step up and talk about a few of her best creative experiences.

Note

As you read Lyn’s stories, a few things probably stood out. One was that it sounded like fun. Good design cannot take itself too seriously. Be playful and try incongruous things. That’s not a skill we can teach you in a book, but we will intersperse sidebars like Lyn’s here and there in the book to give you examples of exercises that went well. Chapter 2 goes into some depth about what makes a good costume, deconstructing more experiences like those that Lyn just shared.

Summary

In this chapter we defined fashion tech and gave a brief history of the converging fields that comprise this interdisciplinary endeavor. From there we moved to introducing different costuming situations that might apply these technologies. We talked about how to use the book and described our design philosophy. We also mentioned a few case studies about great costumes that were decidedly low-tech, to make the point that a good costume will shine through and design is the most important element in a good project. In the next chapter we talk more broadly about what makes a good costume.