Chapter 7. Dealing with Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt

In the last few chapters, we’ve shared a lot of tactical advice. Now it’s time to return to the realm of our emotions. Learning to manage our emotions so that they don’t manage us may be the most important practice for rebels to learn.

Fear, uncertainty, and doubt can paralyze us. We worry, “If I said or did that I could lose my job. Have I gotten in in over my head? Am I jeopardizing my career?” Part of becoming an effective rebel is looking inside and facing our doubts and fears.

Our emotional journeys as rebels often start the moment we realize that our ideas about what needs to be done don’t square with our organization’s current direction or the official view of how things work. And the emotional turbulence never really goes away. We know; those are hard truths, but they must be faced.

Some fears might be unfounded and some will carry risk. The challenge is: how can we manage our fears so that they don’t stop us from doing the work we know should be done?

Ten Fears That Can Hold You Back

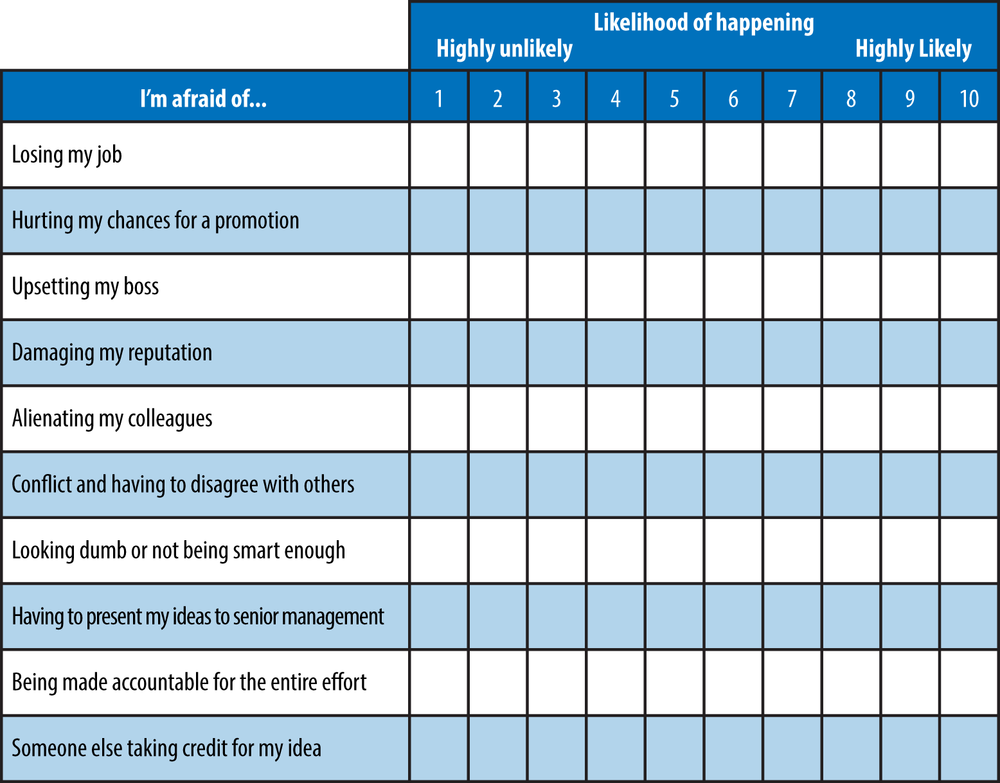

What fears are holding you back?

Take the quiz in Figure 7-1 to determine whether and to what degree each of these common rebel fears affects you. Working through these questions will help you determine your specific fears and assess whether your assumptions are valid. Don’t let an overwhelming yet nonspecific sense of dread hold you back. Be as specific as you can in identifying what may be stopping you and the degree of risk you face.

Losing Your Job

“I’d love to step up and be more of a rebel at work, but I’ve got (fill in the blank: a mortgage or a family or college loans) to think about. I can’t lose my job.” This is the greatest fear for rebels at work.

Here’s the deal: few people ever lose their jobs when they’re trying to put forward ideas for the good of the organization. We hear people voice this concern all the time, but few are fired for trying to improve things at work. Positive intent helps neutralize negative reactions.

The more closely aligned your idea is with what the organization actually cares about, whether it is improving safety or increasing revenue, the less likely you will be fired. If you are viewed as a person who focuses on what’s important to the organization and is going the extra mile to develop ideas to accomplish important goals, you will more likely be viewed as a problem solver than as a troublemaker.

Troublemakers get fired; thoughtful fixers are appreciated for earnestness and relevance.

In a recent Canadian survey of the top 10 reasons why employees get fired, issues such as dishonesty, poor performance, and inability to work with others dominated the list. The one reason cited that does resonate with rebel fears of losing their jobs is “refusing to follow directions and orders,” what is called insubordination in the military.

Some rebels get fired because they attack people rather than going after policies and approaches that don’t work. Be aware that if you attack people personally, they will go after some of your greatest fears: trying to get you fired and publicly questioning your professional competence. It’s also important to realize that the greater the risk your idea poses to the organization, the greater the validity of your fear of possibly getting fired.

Takeaways:

| Frame your message in terms of what matters to the organization. |

| Do not practice insubordination. |

| Focus on achieving progress, not on attacking people. |

Hurting Your Chances of Being Promoted

The fear of not being promoted can be very real for rebels. Whether rebels get promoted can depend on a number of things, some out of our control and some we can influence.

It’s easier with a supportive boss

If at all possible, find a good boss or an influential mentor. It’s best to have a boss who values your creativity and isn’t threatened by your curiosity, honesty, and passion for developing new approaches. When interviewing for a job, focus as much on the person you’ll be working for as the position itself. If you work for a risk-averse boss focused on managing business as usual, your life as a rebel at work will be more challenging. It won’t be impossible but it will certainly be more complicated.

Joan was recently promoted because her boss values her creative thinking, frankness, and experimentation with new approaches.

“I’m being promoted to eLearning Director of the college,” said Joan. “In a coaching conversation with my boss, she passed on advice from our oh-so-traditional provost, who when hearing I was moving into the position, said, ‘She seems to think of herself as a rebel. She will need to let that go as a manager.’ I don’t plan on drinking that Kool-Aid anytime soon, that’s for sure.”

Because Joan’s boss has her back, she has some breathing room to create new programs and show the value of those programs to the students, provided they stay within the limits of what her boss can approve. If she needs higher-level approvals, her boss may be limited in how much she can help. In this kind of situation, we urge rebels to work as quickly as possible to show results. When you can prove that your ideas provide what the organization values, you build credibility and positively influence the naysayers. Positive results increase your chances of being promoted.

Bosses who support us and coach us on how to navigate work politics are invaluable.

It depends on the organizational culture

Rebels are far more likely to be promoted in organizations that talk about the need for innovation and change. In those cultures, we can position ourselves as innovators or change agents. Just as you want to pick the right boss, it’s helpful to pick the right organizational culture. The more future-oriented the organization, the less you have to worry about getting passed over for promotion.

In private industry, the most important indicator of whether you’ll get promoted is how directly you influence revenue. If you’re a rebel and you’re consistently bringing in revenue, the organization is more likely to want to keep and possibly promote you, even if they dislike your rebel ways.

While in grad school, editor Stuart Horwitz worked as an event manager at a swanky Boston hotel. He started changing his look, wearing an earring and a hipster hairstyle, and dressing more like himself than like a Brahmin Boston.

One day the general manager of the hotel walked over to Stuart and gave him a once-over with an expression that clearly conveyed his distaste for Stuart’s style. “You bring in the numbers,” he said to Stuart and walked off. In other words, while he didn’t especially like Stuart, he did like the fact that Stuart’s work generated revenue for the hotel.

It bears repeating: the more you contribute to what matters most to the organization, the less you have to fear about losing your job or not being promoted.

It’s easier if you engage in good rebel practices

Opportunities for promotion and advancement improve the more we control our emotions, practice good humor, gather supporters, exude optimism, and emulate the many other behaviors of good rebels.

What comes to mind when the organization’s leaders hear your name? A troublemaker who’s always losing her temper? Or a sometimes misguided but well-intentioned idea person who gets her work done? If it’s the latter, you are likely to stay competitive within your peer group. (Of course, we rebels would like to be thought of as the far-sighted visionaries who will save the company, but we must remain realistic.)

One last word about promotions. It would be misleading to suggest that rebels, even the best of us, won’t end up losing a few points in our organization’s annual performance evaluation rituals. In fact, it’s critical to understand that risk and come to terms with it. One of the most difficult emotional roller coasters for rebels occurs when we try simultaneously to be true to our convictions and to remain a high flyer at work. Both of us tried to do that and wound up not achieving either goal very well. By our very nature, we value impact and meaning over more traditional measures of success.

As rebels, some of our change efforts will earn positive recognition. Others will not. The question to ask ourselves is whether the effort provides value to our coworkers and organizations and how much we will learn and grow from taking it on.

Takeaways:

| Understand how much support your boss can provide. |

| Evaluate the receptivity of the organizational culture. |

| Show positive results as fast as you can. |

| Be a good rebel. |

Upsetting Your Boss (or the Powers That Be)

Even if we’re valued performers, the fear of what can happen when we upset our boss or senior managers is real.

When our boss is unhappy with us, it’s as bad, sometimes even worse, than fighting with a spouse. The world feels off and we can’t relax. We walk on eggshells and obsess over what we can do to get things back to normal. We spend time worrying whether we’ll be able to repair the relationship. We begin thinking about whether we should update our resumes, reverting right back to that fear of losing our jobs.

As rebels, we rightly fear upsetting our boss, or our boss’s boss. They can make our lives miserable in so many ways.

But how real is our fear of upsetting our boss? Start by considering what most concerns or upsets her and look for ways to avoid those triggers. Most bosses:

- Hate it when we challenge their ideas in front of their bosses; they think it makes them look bad

- Want details of our idea spelled out, or to know that we’ve researched how other companies might be using the idea we’re proposing; generalized “big ideas” annoy them

- Hate last-minute surprises and not being forewarned about possible risks

Make it your business to learn what your boss dislikes as well as what he likes. The more you understand what upsets your boss, the more likely you won’t do it.

One last point about fearing management. We have found that the more senior the executive, the greater the rebel’s fears about upsetting or displeasing that person. Presenting an idea to a middle manager might make you nervous, but presenting that same idea to the executive vice president would make you extremely anxious. Don’t be afraid of presenting to senior executives. Remember that they got to where they are by being open to new ideas.

Takeaways:

| Make sure you support the bottom line, or whatever results “count.” |

| Understand your boss’s red lines and don’t cross them. |

| Invest in learning how your boss likes to receive ideas and feedback. |

Hurting Your Reputation

If I stand up for an idea that is foreign to how we do things around here, will I hurt my reputation? Will I be taken seriously? Will people think I’m a troublemaker? Is the effort worth the potential risk? These fears about our reputations can stop us cold.

John, a rebel manager in a healthcare company, was elated about a new program that his management team had just approved. “This is a ‘bet my reputation’ kind of an idea,” he explained. “If this idea doesn’t work, my career at this company will be over.”

John didn’t need to worry about ruining his professional reputation. He is known as a positive, thoughtful, trustworthy guy who delivers on his promises, and when things don’t go as planned, he gives his bosses a heads up as early as possible so that they aren’t caught by surprise. He has a track record of introducing and managing successful programs.

Note

The greater your existing reputation capital, such as a history of creating successful programs or managing projects, the less you have to fear about your big rebel idea hurting your reputation.

Some rebels fear being seen as a troublemaker. As we said in Chapter 1, rebels are focused on creating positive change for the organization, not wreaking havoc and destruction as troublemakers do.

But the fear of being seen as a troublemaker may be valid if people in the organization view change and new ideas as “trouble,” which they may, and which you have no control over.

One way to evaluate how much your ideas would help or hurt your reputation is to ask yourself (and maybe some trusted friends at work), “On a scale of 1 to 10, 10 being the best, how much would the organization benefit if my idea is successful?” If you answer 8–10, it’s likely worth the risk. If it’s 4–7, take time to consider it more before charging ahead. And if it’s 1–3, it may not be worth it.

One of the questions job interviewers often ask is “What was your biggest failure?” If your idea flames out and you have to look for another job, know that you will have a fascinating story to tell if your idea was in the 8–10 range.

Takeaway:

| Remember that everything you say and do will be seen and evaluated in the context of everything else you’ve said and done. Work on building a positive reputation, which makes for positive context. |

Alienating Colleagues

Often we have no control over how our coworkers will respond when we are in full rebel mode, working intensely to get something important changed at work.

The fact is that being a rebel is a calculated risk when it comes to how others see us.

We’ve found supporters and detractors during our careers. Letting the lure of the former and the fear of the latter influence your work is not helpful. It’s not predictable and it’s ego- rather than mission-driven.

Some people may envy our courage to tread where they wish they could. Others may not like the fact that our ideas would require them to do their work differently. We can’t control how others may feel.

What we can do is to stay positive, appreciate and acknowledge our coworkers’ ideas and contributions, help others wherever we can, and act with integrity and in the best interest of our organization.

Takeaways:

| Build relationships and trust. |

| Think through what you say and do and how you say and do it, because it will affect others. |

| Remember that ultimately you cannot predict or control how others will respond to you. |

Having to Deal with Conflict

We discussed this issue in Chapter 6, but it still deserves a place in any list of the rebel’s greatest fears. Fear of conflict stops many rebels from pursuing ideas that could benefit others. Indeed, the desire to avoid conflict or tension of any kind is why the culture of consensus pervades so many organizations today. (And we wonder why organizations aren’t changing fast enough or why employees are disengaged.)

This desire inevitably seeps into the workforce as individuals take their cues from the behavior of those in management. Agreement becomes the ultimate good, and disagreements, particularly in public, are criticized as unprofessional.

It is important not to internalize these values. It’s absurd for us to censor ourselves just because we know people will likely disagree with us.

What we need to do instead is to reframe conflict as a necessary and potentially fertile part of any change process and handle conflict productively so that we avoid its potentially destructive consequences.

Takeaways:

| Recognize that conflict is a necessary and valuable part of any change process. |

| Do not censor your actions or proposals because people may disagree with them; instead, learn from them and incorporate their ideas to make the ideas better. |

| Learning how to handle conflict productively is an important rebel skill. |

Looking Stupid

While the discomfort of engaging in debate and conflict is especially intense, the fear of looking stupid or of not being smart enough also stops many of us from speaking up.

We’ve both been in situations where we held back, concerned that we might not have the answers and could come across as misinformed troublemakers. But over our long careers we have found that, more often than not, asking a question makes us look smarter. Other people in the room often have the same question but didn’t have the courage to ask it.

Being a rebel in the workplace rarely looks like reinventing your company, creating new business models, or solving other major challenges. Mostly it’s simply being willing to raise our hands and put words to what we and possibly others are feeling, and offering a different way of looking at a situation.

People often look dumb when they don’t have all the facts, ask questions not related to the context of the discussion, or complain incessantly. However, if your intentions are positive and you’ve done some homework, you won’t look dumb—just concerned.

Takeaway:

| We always count the potential cost of speaking up, especially as a lone voice. Isn’t it just as important to count the cost of not doing it? |

Presenting to Senior Management

Some people say they worry that if they bring up a better way to do things, their boss will say, “Good idea. You go present that to the senior management team.” Often this is code for, “I don’t want to deal with your idea so I challenge you to present it to the executives and hope that you won’t bother.”

That dare conjures up our earlier fears about upsetting the powers that be.

Being asked to present your ideas to senior management is a good thing. It’s not to be feared, just prepared for. Think of it: this is what you’ve been waiting for, a chance to present your ideas to people who have the resources and authority to give them life. You are likely the best advocate for your cause. If you’re not, ask someone who is expert to provide support.

If your fear is really about public speaking (a fear for about 40 percent of the population), that can be overcome with good preparation and an understanding of what management cares about.

The thing to remember when presenting to senior management is that they don’t like long presentations about how your idea will work. Avoid getting bogged down in execution details. We’ve seen too many rebels lose the interest of leaders by going into long explanations of the problem and exactly how their ideas would solve the problem.

Rather, senior leaders will want you to cut to the chase and address some important questions:

- How does this help us achieve one of our important goals?

- Is it feasible?

- What do you know for sure about the situation and what needs to be learned?

- What are the risks?

- What kind of resources (financial and people) will it take, and is the investment worth the likely outcome?

They may also want to know how long it would take to implement your idea and how you plan to measure progress and success.

Keep the formal part of the presentation short, and leave time for comments. If there are questions and lively discussion about your idea, this signals that they are intrigued and interested. To wrap up a meeting about an intriguing idea, senior leaders are likely to ask you, “What’s the next step to assess this idea?” or “What do you need from us to move this idea forward?” Be prepared to answer those questions. They will keep your idea moving and boost your credibility.

One last tip: stay positive. People—at all levels—respond more open-mindedly to positive people intent on helping the organization and the people in it. Senior leaders will actually more clearly hear your idea if you remain positive and focused on the vision of the idea. Whatever you do, never succumb to finger pointing, blame, moaning about problems, or other types of drama. When conversations descend into drama, senior leaders may view you as a whiner rather than a competent person with ideas worth considering.

Tips for overcoming this fear:

- Be prepared.

- Be positive.

- Be brief.

- Be sure to thank them at the end.

Now Go Make This Happen

A related concern is, “Gosh, what if managers like my ideas and ask me to implement them?”

This is a valid fear. The good news is that it is almost completely under your control. If you have prepared correctly, researched your ideas, and created the right kinds of alliances in the organization, you can articulate how the idea can best be implemented.

We’re reminded of that wonderful scene toward the end of Finding Nemo when Gil and his aquarium mates have escaped the dentist’s office and are bobbing in the bay in their little individual plastic bags. “Now what?” they ask. As a rebel at work, the ability to think ahead is one of your greatest strategic assets.

You may be asked to run the entire effort, or if you’ve done your homework, you may be able to suggest a better way to get the job done without you. If implementation isn’t your strong suit, partner with someone who is. Create a “hand-off” plan.

Takeaway:

| If you are the right person to implement the plan, say thanks for the opportunity. If you’re not, come prepared with recommendations about how to move forward. |

Someone Else Taking Credit

We rebels don’t need to run everything or even to be recognized for every idea we have. One of our real values is seeing opportunities and ways to solve problems before other people and signaling for help. As future thinkers, we’re like scouts who spot a small brush fire that could turn into a wildfire.

Several successful rebels have told us that one of the best indicators that they’re succeeding is that others in the organization start talking about their ideas without giving them proper attribution. We call that a rebel win.

Most rebels are not one-trick ponies. We keep coming up with ideas and often become known as the go-to people for new ideas on how to tackle gnarly problems.

Both of us are much happier letting someone else run with our ideas. Remember the three types of thinkers we mentioned in Chapter 2: future, present, and past? As future thinkers, rebels spot what’s coming and create ideas for how to respond to that change. Let the present thinkers figure out how to implement the ideas and manage the projects. That’s what they do best, not us.

Takeaway:

| Share the credit and know when to pass the baton to others who are ideally suited to making big ideas real. This frees up your energies to uncover the next big thing. |

Dealing with the Devils of Self-Doubt

Fear is one thing, but doubt is another. What really stops us is often doubt, which can be like a dense fog, making us feel lost and stuck.

Fears are specific, and once we are aware of them, we can usually find ways to tackle them. Afraid of presenting to senior management? Prepare well, get coaching tips on how they like information presented, practice, and you’re on your way to conquering that fear. Afraid you might hurt your reputation? Ask trusted work friends for their views about how solid your reputation is and how much your reputation might be at risk when you stand up for this particular idea.

While fears are specific, doubt is undefined. We’ve found four techniques that are useful in overcoming doubt:

- Lean on your dominant strength.

- Know your “give-up” line.

- Change your environment.

- Cleanse your assumptions.

Lean on Your Strengths

When in doubt, look for what has worked for you before. What did you do to move through that earlier storm of doubt? Which of your strengths helped propel you through these periods, and how have you leaned on that strength before to get through a period of doubt?

We all have about five key strengths, according to psychologists Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman, authors of Character Strengths and Virtues. Knowing your strengths helps you push doubt aside and lean on the strengths instead. One way to determine yours is to take the assessments offered at the Authentic Happiness website. Table 7-1 provides a list of strengths to consider.

Creativity | Curiosity | Open-mindedness | Love of learning |

Perspective | Bravery | Persistence | Integrity |

Vitality | Love | Kindness | Social intelligence |

Citizenship | Fairness | Leadership | Forgiveness |

Humility | Prudence | Self-control | Appreciation of beauty and excellence |

Gratitude | Hope | Humor | Spirituality |

[a] Source: Christopher Peterson and Martin E. P. Seligman, Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). | |||

Lois’s dominant strength is her love of learning. When she falls into periods of doubt, she turns to research and learning, which helps her see new ways, test ideas, and jumpstart her confidence. Carmen’s is fairness. Another rebel friend’s strength is perseverance. When in doubt, he recognizes that if he keeps pushing forward, small step by small step, he is likely to accomplish his goals.

When we’re aware of and appreciate what works best for us, we can keep going back to those practices. Most of us, however, get through a self-doubt cycle but don’t pay attention to what helped us. Next time, make a note of what helped, because that technique will probably work for you again.

Identify Your “Give-Up” Line

When we are at the end of our rope, we often mutter something under our breath. That’s our “give-up” line. The subtext for the give-up line is “I give up” or “I quit.” Here are a few give-up lines:

- Gawd, these people are stupid.

- I can’t believe I’m wasting my time here.

- I just don’t care anymore!

All rebels can benefit from hearing that little articulated outburst of emotion that signals growing frustration and self-doubts. Identify it and get it under control as soon as you can. You may not be able to prevent cycles of self-doubt, but you can shorten them through self-awareness.

Change Your Environment

Another practice in times of doubt is to change your environment. Have you ever heard someone say, “What you need is a change of scenery”? There’s plenty of wisdom in getting physically or mentally away from what we’re obsessing over. Move away from the issue that’s drowning you in doubt.

Read a good book. Turn off your devices. Take a walk. Have lunch with someone you enjoy. Meditate. Just get your mind off the nagging rebel problem for a while.

Cleanse Your Assumptions

In much the same way that nutritionists urge us to go on mini-fasts to rid our body of toxins, we need to do a mental and emotional cleansing to clear our minds of ideas and habits that are holding us back. What assumptions are blocking you? Which of your deeply held beliefs are in the way? What seeds of doubt are beginning to take root?

Has your idea hardened into an assumption? Is your new idea still relevant? Have you been pushing the same set of “new ideas” for 10 years? Perhaps the reason why you’re not getting an audience is that your ideas are no longer new or relevant. This is not an uncommon problem for rebels who become so attached to their original thesis that they forget that even “new ideas” can become old. A good rule of thumb you might find useful: if you’re sincerely testing your assumptions, some of them should fail.

Do you lump everyone together by thinking that “no one understands”? Are you ignoring potential supporters because you don’t think they would understand your ideas or you think the work they do is not relevant to your goals? One of the most interesting ways to advance a new idea is to start someplace marginal to the larger organization. Starting small or starting stealthy is often a good rebel strategy for building support. There may be supporters you are overlooking; just because people are quiet doesn’t mean they’re not listening and interested.

A more rigorous approach to driving change, backed by years of research, is to use the Immunity to Change model developed by Drs. Lisa Lahey and Robert Keegan, professors at the Harvard University School of Education and authors of Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in You and Your Organization.

Their straightforward model walks you through what you’re unconsciously doing to protect yourself from having to change (the immunity) and helps you pinpoint the deep-seated assumptions that stop you from doing the things that will help you achieve your big goal.

“People rarely realize they hold big assumptions because, quite simply, they accept them as reality. Often formed long ago and seldom, if ever, critically examined, big assumptions are woven into the very fabric of people’s existence. But with a little help, most people can call them up fairly easily,” say Lahey and Keegan.

We want to assure you that everyone, no matter how successful, has fears and doubts. This discomfort is a sign that you’re being true to your convictions and doing meaningful work. Fear and doubt can stop you, they can give you energy, or they can just be neutralized. The only thing any of us can really control is how we think. Name and acknowledge your fears, do a little investigating to see how real they are, and then think about the value of what you’re trying to accomplish.

And sometimes just pretend that you are a person who can.

Questions to Ponder

- What are the top two fears that hold you back from leading change at work? What can you do to reduce the risks associated with each of these fears?

- What’s your give-up line? What is happening around you when you start using it? Now that you know what it is, what can you do differently when you hear yourself start to say it?

- What hidden assumptions might be blocking you from achieving what’s especially important at work? How can you test those assumptions to see if they’re really true?

- What is your dominant strength? How might you use that strength to increase your confidence?