Chapter 3. World Context

In the previous chapter, we looked at how to reason in ways that will be applicable throughout your strategy patterns work. Now, we get to the heart of the creation patterns.

The patterns presented here represent the broadest context—that of the world outside your own company. We start here to ensure your strategy work is properly grounded and that your more specific, local strategy choices consider important trends, themes, and vectors beyond the walls of your corporation, and even your industry. They’ll give you more empathy and understanding with your customers. These patterns will also help shape your views to ensure the technology strategies you create are the most applicable and supportable. Additionally, presenting your homework in these patterns will show your executive team that their concerns are your concerns, giving both of you the confidence that your technology strategy is aligned with the business, and not only a shopping list of shiny objects.

While these patterns could seem distant from your comfort zone in technology, that’s part of the point. People who are strategists for a living base their business decisions on this kind of work. Rooting your work in analyses of the climate and directions the broader world is taking will help make your strategy thoughtful, sound, and complete. Understanding the context and the language in which the business operates will give you a terrific boost in making your architectural recommendations best support your organization. I hesitate to say that you, as a technologist, can do very well to think like a businessperson and talk in their language. That’s because, after all, if you’re in a position to make strategy recommendations in your organization, I’m sorry to tell you, but you’re already a businessperson.

There are four patterns we’ll look at to help ferry you in your journey to the dark side of business:

-

The PESTEL analysis is a simple framework for understanding the broad political, macroeconomic, social, and technological trends operating in the world outside. It helps give you necessary context to make your technology direction in harmony with the conditions informing your business. The work you do here can feed Scenario Planning.

-

Scenario Planning is a fun, collaborative exercise that will help you imagine different futures so that you can plan how to encourage the happy ones and shore up against the scary ones. The work you do here can feed the Futures Funnel.

-

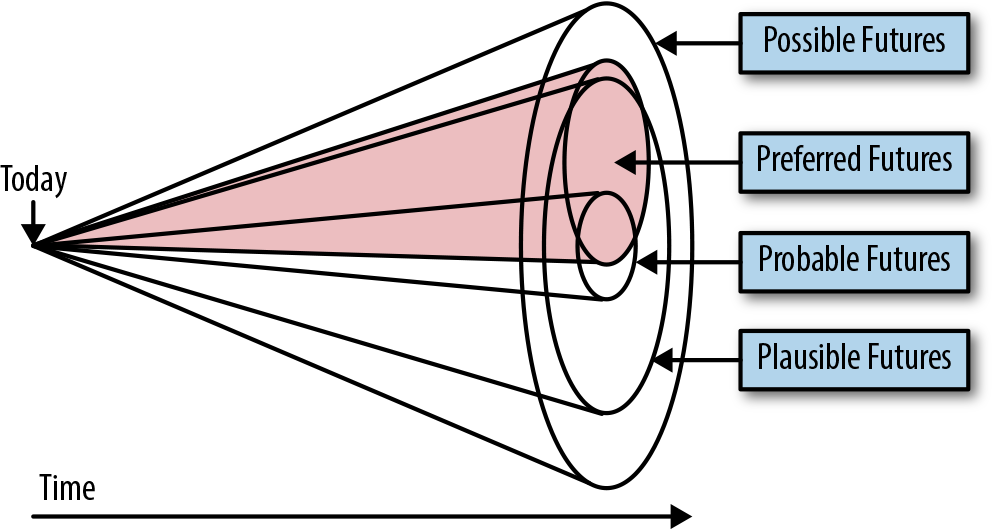

The Futures Funnel is a diagram that presents in one compelling picture your conjecture of different possible ways your company’s future could play out. I’ve found it to be a quick, easy, and provocative way to have a level-setting conversation with executives to ensure that you have the right focus and common understanding of the business vectors.

-

The inverse of the Futures Funnel is Backcasting, in which you posit a desired future state and trace backward to the current state to see what you’d need to do to make it come true.

If you are creating a broad multiyear strategy, or need to make a presentation to your colleagues or peers in your industry about where you’re headed, these patterns are quite useful.

PESTEL

The PESTEL analysis was created in 1967 by Harvard Business School professor Francis Aguilar. You use a PESTEL analysis to answer this question: What strategic direction is suggested by the current and anticipated Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, and Legal climates?

PESTEL offers a simple, memorable framework with which to analyze the key drivers of change in the context in which your business operates. It’s used by “businesspeople” (of which you are one) to determine when to launch a product, when to create or update a brand, when to shore up investments in one area of the business, and when to perform organizational planning, marketing planning, and so on. Clinton Anderson, President of Sabre Hospitality and 20-year Bain consulting veteran, defined strategy to me as “the purposive allocation of resources to help achieve a certain aim.” The PESTEL isn’t about allocating those resources: it comes before that. It helps you see what the weather might be, so you know to pack an umbrella. It’s one of the strategist’s starting tools.

The PESTEL analysis is in this chapter because it isn’t specific to any particular industry and is foundational. But if you’re in the business of making pharmaceuticals, the aspects of the PESTEL climate you’ll find relevant will differ from those of the strategist from a telecommunications company. You will create your PESTEL while viewing each category through the lens of your own industry. That is, to take one of the six PESTEL elements as an example, there’s no such thing as “the economy” in a sense—that’s a reification. But you can bring your comments back to the specific ways a given trend or climate within each category might impact your industry and your customers. For instance, if you’re in the travel industry, fluctuating gas prices might affect your customers and your business. How will you mitigate this? If you’re making software products, gas prices are likely a weakly linked relation, and therefore an unnecessary, irrelevant place to focus your economic analysis. You’re not analyzing “the economy” itself—you’re using the economic landscape as a context for one aspect of your business.

PESTEL Is MECE

PESTEL itself is MECE—all of the six subcategories it comprises together are on the same level of abstraction, they shouldn’t overlap as you perform your analysis, and they represent a complete, good enough picture of the broader world.

Let’s look at each aspect more closely by offering some examples of the types of questions you can ask. There’s no formal framework within PESTEL to help you answer these questions. As an idea, it’s really not much more than the acronym.

- Political

-

How will government policy change incentives for different industries? Consider trade and taxation changes. How might terrorism and military actions impact your contracting business? Regulation in China is different than in other areas, and its firewall means you might need to create a separate copy of software. How does that change your deployment strategy? How would new government sanctions deprioritize or delay your president’s interest in international expansion? If a state travel ban on Mexico is instituted, how would that modify your strategy?

- Economic

-

Do consumers have the discretionary or disposable money to buy your leisure electronics or luxury product? What is the cost of financing to your customers who need to build an office to create space that your software helps lease? What are foreign exchange rates such that people might become less engaged in international travel, stay home, and drive more? What about unemployment levels and projections, level of GDP, and other economic trends?

For example, your research might uncover the following data points:

-

Travel and tourism investment in 2016 was USD 806.5B, or 4.4% of total investment. It should rise by 4.1% in 2017, and rise by 4.5% per year over the next 10 years to USD 1.3T in 2027.

-

Millennials save at a higher rate than other generations: One in six millennials has saved over $100K, and millennials save money at a rate twice that of baby boomers.

-

By 2025, the eight largest cities in the world will have a total population equivalent to what the US had in the 1960s.

These are unadorned, uninterpreted facts. Once you have those data, you can put your thinking cap on, draw some conclusions, and look to gain insights about them. That might look like this:

-

Fluctuations in the US dollar, Euro, and other foreign currencies can create sudden pockets of places where travel unpredictably becomes undesirable for a period of months.

-

Introduction of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies could require additional infrastructure if it enters the mainstream for payments.

These are insights because they’re making weak claims and projections about possible outcomes.

-

- Social

-

What are the changing attitudes of the people who constitute your primary base of customers, vendors, partners, and employees? Consider generational trends, family trends, and educational trends. Do the differing tastes and habits of millennials cause your CEO to reconsider certain aspects of the business or create a new brand? How health-conscious are people? What are the dietary trends? Are people more active? What are the educational trends? If most people read on a cell phone, or learn through watching videos, or live with their parents until they are 30 at a far higher rate than they used to, how do you imagine your CEO will find that relevant to the business, and how might that in turn change your strategy?

- Technological

-

This one may seem redundant for us, but it’s often not. We get focused on the work at hand, and if we’re heads down in a mobile tech project or a legacy migration, we may not be keeping up with the latest in IoT and artificial intelligence. Consider this as if you are not a technologist, so you can more objectively look at technology trends from a business perspective. Work to understand how broad populations (countries, generations, customer segments) are using different kinds of technology and what advances are being made in popular areas of tech. Go to meetups and tech conferences or watch them online afterward, read Forester or Gartner papers, and McKinsey Insights, and check out websites such as O’Reilly, ThoughtWorks, Tech Crunch, and others as an easy start. They publish many whitepapers you can access even if you don’t have a membership.

- Environmental

-

What are the ecological influences on your business? Are climate changes affecting your industry? How likely was it that trends toward sustainability in the consumer mindset and efforts to produce low-emission vehicles contributed to the rise of Tesla and its technology strategy with laptop batteries for electric vehicles? Are your customers or fulfillment associates and suppliers affected by the weather in ways that your products or logistics software can better support?

- Legal

-

What laws are hotly debated recently that may change? Again, try not to think from a technologist’s view, considering only things like net neutrality (though that’s a good one to be aware of, especially in the internet business). What recent laws have been passed; what sanctions have been imposed on different countries? What new laws are brewing or anticipated? GDPR likely has an impact on your big data, analytics, and machine learning strategy. If you’re a franchisor, the co-employment laws would make a difference to your technology strategy, so maybe don’t suggest writing your own franchise employee scheduling application. Does the legalization of marijuana potentially change your business? What about antitrust laws if you’re interested in a merger or acquisition?

Creating the PESTEL

Making your PESTEL document is much like writing a concise, high-level research paper at school.

First you do the research, and then you write it into a short analysis paper. The length will depend on how broad the strategy is that you’re doing at this moment.

Next, you put those points into slides for your Strategy Deck. The PESTEL should go in the appendix to support the technology recommendations and claims you make in the body of the deck. People won’t likely want to read it up front—they’ll start skipping to the conclusion, so you may as well anticipate this and put it in the back.

Researching for PESTEL

These areas of research may be new to us as technologists.

The kind of thing you’re looking for are broad statements, with data and sources, about the state of the economy and political outlook. This is how CEOs talk and will help give you the context that can inform your decisions.

Your job here is to quickly research for key stats that serve as signals, or indicators, that you can use in your Strategy Deck to ensure that you make technology decisions properly within that context and do not disregard it. CEOs and executives are interested in things like this:

-

Are baby boomers living longer such that more people will be in hospitals or nursing homes for longer, and how will that change their business?

-

How are people in the millennial or digital native generation using technology differently? How do their expectations, habits, lifestyles, incomes, savings, gender identities, and political attitudes differ from their parents’ as they grow to become the dominant consumer base?

-

Are people moving to the cities or the suburbs? What is driving that?

-

What areas of the world are seeing organic (people being born) and inorganic (people moving) population growth? How does this change the languages, internationalization, and localization that they may ask you to support in your software? If you globalize, you might need a plan to roll out one continent at a time. Which ones, in which order?

Your PESTEL should include statistics to support a long-term outlook, say, two- to five-year projections. For the Political, Economic, Environmental, and Legal parts of the analysis, there are several sources you can use. Find sources in economic forum conferences, or in published research papers, or in outlooks published by McKinsey, Bain, and BCG on their website. Also look for those published as “Global Economic Outlooks” by the likes of Ernst and Young, Deloitte, Forbes, and the International Monetary Fund. For the Social outlook, you can find good sources in the International Labour Organization, Pew Research, Pew Social Trends, and SIRC.org in the UK, and check out resources such as Cognizant’s Future of Work website. Note that many of these web searches readily produce a variety of other options depending on your needs. Because the methods and sources used vary, and because you want to make it easy to validate and look up later, don’t forget to cite your source.

The PESTEL probably needs to be updated only once per year, or following some major historical or disrupting event.

Applying the PESTEL

You want to start with a PESTEL analysis early in your strategy work. Write it out as a document, preferably in a word processor first. I’ve found it helpful to create a scrapbook to use as a kind of “raw material dumping ground” to generate a lot of data and material quickly. Then, in a second round, you can go through and refine it, distill it down to the connected points that start to paint a picture of the landscape for you. Eventually it will become a set of slides after you have gathered your raw material. You will use it in a few different ways.

First, you’ll want to have the PESTEL document yourself so you can refer back to it later as you continue applying other patterns to create your strategies. Its primary purpose is as a reference and contextual guide for you in executing the next stages of your strategy creation. Then you’ll put it into slides in your Strategy Deck appendix. It will ensure you are making choices from a business perspective, and considering what executives are concerned with.

Next, you can use the PESTEL document as an independent, standalone analysis. Once you’ve got a draft, you can use it as a token to gain consensus from others in the business. Share it with your nontechnical colleagues in product, strategy, or sales, or with members of the executive team, and ask for feedback to see if you have considered the right things, didn’t leave out anything, and are drawing conclusions that make sense to them. They may know more about this area, as technology is a small part. Validating the PESTEL up front ensures you’re building on a solid foundation.

If you’re creating a holistic, longer strategy (say, a one- to three-year outlook), you’ll doubtless end up creating a deck to represent it. You can include these PESTEL slides in an appendix of your Strategy Deck for your executive audience so they can recognize the homework you’ve done. It will give you and them confidence that you are thinking from a business perspective and that your subsequent technology recommendations are therefore the right ones for them to pursue.

So the PESTEL work is in three parts:

-

Gathering the data through research while doing your best to not mix your biases and assumptions with it.

-

Stating your insights.

-

Making local recommendations based on your insights. These will roll up together to form your business strategy.

There is likely a business strategy already, created by your Chief Strategy Officer. So it’s important to check in with her to make sure that you are in alignment, see things the same way, and can cross-validate your findings. Sure, you could just use her existing business strategy, but it may not be written down or accessible, and this helps you learn the language of the business and be more empathetic with the broader concerns so that your tech strategy develops more naturally from a business-oriented view. The fresh perspective will present a good opportunity for a rich conversation. Plus, it’s fun.

Scenario Planning

Of the many strategies in the world, the default strategy is consistently the “Do Nothing” strategy. We don’t wake up every morning and evaluate whether or not we should still live in this house, eat breakfast, and continue to have a dog. We think, “This is my life,” and we continue our established routines. Maintaining the status quo—the Do Nothing strategy—is far and away the dominant strategy of people and corporations.

There are two problems with this strategy. The first is that it creates optimism bias. Worse, it deepens our belief in established and familiar patterns, enervating our ability to perceive change and anticipate the unexpected. People assume the future will look like the past—recall what happened to Russell’s turkey (“4. Probability of Each Outcome”). Instead, can you ask “What if?”

Your technology strategy will be richer and more layered, and will support the business in a more relevant and powerful way. You’ll choose to spend time and resources on stuff that matters more.

Scenario Planning is an an organized way of asking the question “What if—?”

Its history traces back to the 1950s at the RAND corporation, where a fellow named Herman Kahn devised the tool to test a variety of military strategies that could be employed against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. You can read more about the history of Scenario Planning in the Harvard Business Review.

You may recall the movie War Games from the 1980s in which the computer played the game “Global Thermonuclear War” against itself (in a kind of generative adverserial neural net, I surmise) millions of times in order to determine the winning strategy (conclusion: there isn’t one). This was a popular computer version of military Scenario Planning in action.

This is one basic format for conducting Scenario Planning in your organization, based on my experience several years ago with a McKinsey engagement. It starts with the consulting group conducting a lot of research and interviewing key members of the leadership team. This process takes several weeks. Then the group schedules a two- or three-day workshop for the leadership team, and gives us a presentation for an hour or so that represents its findings and hypotheses. This serves as a starting point and level setting for the exercise. Then we break into small groups, generate a bunch of scenarios, and work through a variety of them to imagine how they might play out. We then reconvene to distill the ideas down to a few that sound interesting and important. You can do this with a private voting round. Then with the remaining few, we divide into teams to figure out good arguments for why our scenario should be the one to win. The leadership takes this as input and thinks about it. As a result of this workshop, my company’s leadership at the time decided to go into an adjacent line of business and buy a company.

That’s the basic process you can use for Scenario Planning.

Steps for Scenario Planning

Scenario Planning is not rocket science. It’s mostly about carving out the time for the leadership team to get out of daily operations and think about the future with a diverse crowd so they can gain additional perspectives on how well they are positioned in the market, what competitors or substitutes might be coming for them, and what opportunities they have to grow the business.

To get into a bit more detail, you can create a map. Pick one of the scenarios you’ve imagined, even if it’s a “weak signal.” You’ll need a basic shared understanding of a barrier for plausibility. Imagine what three possible impacts of that would be. Then do the same for each of those impacts to create a set of second-order impacts that result from the first. You’re projecting the weak signals out into the future to come up eventually with a tree of how things play out in the world, using your PESTEL (see “PESTEL”) as a backdrop. In our logical architecture of the pattern catalog, this pattern operates in the sphere of the world, so you don’t want to confine yourself to only your industry. You’re on the plane of global, large-scale trends. There’s also nothing here specific to technology.

During the workshop you want to:

-

Review all the trends out in the world that could affect your company’s business. You can get this from your PESTEL. Look at different geographies, different industries. Consider how different trends might disrupt, reroute, or otherwise hurt your business. This is an intelligence-gathering exercise. Define a strategic problem on this basis. It should come in the form of a sentence such as “Should we pursue an alternate growth strategy?”

-

Create a list of the trends with your estimation of the impact.

-

Build the scenarios together as a list. This is not something you delegate to others. Given their daily book of work, more junior folks may not be able to raise their visors enough to see far. Don’t allow yourselves to succumb to group think, or to avoid alternatives that are plausible, but less so, in favor of the most likely or dramatic one.

-

Assess the impact of each scenario. Develop alternate paths for each as in a Logic Tree (see “Logic Tree”). Do not give too much weight to things that seem very improbable. If that sounds counterintuitive, it is not uncommon for teams to get bogged down trying to suss out details or estimate probabilities for scenarios and impacts that are largely unknown. Just give it a tag and move on. You can do this more easily by assigning different levels of uncertainty, relative to the other items instead of something like a raw score.

If you’re not the CEO, then pulling together the top 10 or 12 leaders in the company to run this workshop will be a challenge. Putting three McKinsey consultants in a room for a month to do research and dream up hypotheses will run you around $500,000. If this isn’t in your budget, you can hold 50,000 bake sales to raise the money, hire a cheaper firm, or just do it yourself. For our purposes, we’ll treat it this way. But this isn’t one you do alone. Put together a half-day workshop. Invite the clever people, making sure that it’s a diverse audience of cultural and work-role backgrounds. Then brainstorm for a bit and follow the preceding outline.

I recommend you do a poor man’s version of the initial “imagining the future” deck by bringing in experts from various parts of the business and technology to create and present their own short deck on their vision of the future. Having directors put this together is a wonderful way to invite them into the leadership team, and give them a place to shine. This has the added benefit of giving you a good sense of who the go-getters on your team might be, who the next leaders might be.

Look for the weak but plausible signals you hear from them. Then use inductive reasoning to forecast each of the weak signal’s impacts. You’re not picking your favorite, or one that you want to see happen. You’re forecasting the future. If it calls for rain, you gotta say it’s going to rain, even if you wanted to go to the beach.

If you’re in a legacy company that has a cash cow and isn’t the most innovative, this could be the workshop that saves your company and helps point it to the future.

The value of Scenario Planning is real, but indirect. Use the results not so much in their own right—no one is going to look at the poster boards afterward—but rather capture them into a set of slides, which again you can put in your Strategy Deck appendix or just save to refer to as you conduct your technology strategy. It’s perfect homework to feed a Futures Funnel (see “Futures Funnel”) and a Backcasting (see “Backcasting”).

That said, Scenario Planning does create value in these ways:

Futures Funnel

The Futures Funnel pattern is closely related to Scenario Planning (see “Scenario Planning”), and is really just a visual representation of the final, distilled outcome of that work. It’s a fun and compelling view that is useful for busy executives. You need to be able to fit it on a single slide, as shown in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Your Futures Funnel looks just like this before you add your descriptions

The funnel in the picture acts like a Venn diagram, of course. Think of each of the circles at the end of the funnel as a set. Your Futures Funnel will look just like this. Literally just plunk this down into your deck, with the addition of only one thing: a brief description of each of the four futures.

The widest set is all the things that could happen, the possible futures: any future can eventuate only if it’s possible.

Within that, it gets slightly more complicated. The next smallest subset is the plausible realm. This is the set of things that are more reasonable to expect to happen. It’s possible that a giant lizard rises up from the ocean and squashes Portland, but it’s not plausible. We don’t think about the ones that aren’t plausible too much.

You’ll notice there is one key difference between this and Scenario Planning. Here you are adding the value judgment of the preferred future. These are the things you want to happen. This, sadly, is the tiniest little port for us to try to land. It stretches across things that are plausible and probable and preferred, which is great, and things that are preferred but silly.

Next there are the probable outcomes. This is the set of things likely to happen, some of which we want, and some of which we don’t. Both areas are the place to focus. To help you think deeper about the preferred and plausible outcomes, and the preferred and probable outcomes, I refer you to the Backcasting pattern (see “Backcasting”).

Ignore any thought of what’s preferred but not plausible: this is the realm of fantasies. I suppose you could win the lottery, which might be preferred, but it’s not reasonable to suppose that you will, and there’s not much to be done about it anyway, so there’s no point in thinking about it.

But how do you come up with the material here? I suppose you could just put your thinking cap on, sit down, and invent what all the possible, plausible, probable, and preferred futures are going to be. And if you’re a futurist and can do that, that’s terrific. But if that’s not working for you, Table 3-1 shows a little framework to help you as you consider what this set of possible futures might be.

| Internal | Conceptual | External |

|---|---|---|

| Financial, organizational resources | Correlations | Potential futures |

| Current and roadmap architecture | Causal chains | Expected customer behaviors |

| Current and roadmap product portfolio | Expected competitor behaviors |

To help you fill these out, I recommend you use some other relevant patterns here: the SWOT analysis (see “SWOT”) and Porter’s Five Forces pattern (see “Porter’s Five Forces”). Those will really help jump-start your Futures Funnel.

Beyond its role as representing the outcome of a sophisticated Scenario Planning exercise, a second use of the Futures Funnel is to act as a substitute for Scenario Planning. If you have very little time to turn something in, or you are not working on a strategy of broad scope at this point, just do a Futures Funnel instead. It acts as a less rigorous (not at all rigorous, but that’s fine for many situations), mini–Scenario Planning exercise. Used this way, instead of the expensive multiday workshop, you implement it by just sitting alone in a room, thinking about what might happen, what’s plausible, what’s probable, and what’s likely. And then write it down and ship it.

Backcasting

We know what forecasting is: you start in the present and try to look into the future and imagine what it will be like. Backcasting is the opposite: you state your desired vision of the future as if it’s already happened, and then work backward to imagine the practices, policies, programs, tools, training, and people who worked in concert in a hypothetical past (which takes place in the future) to get you there.

It’s a wonderful tool.

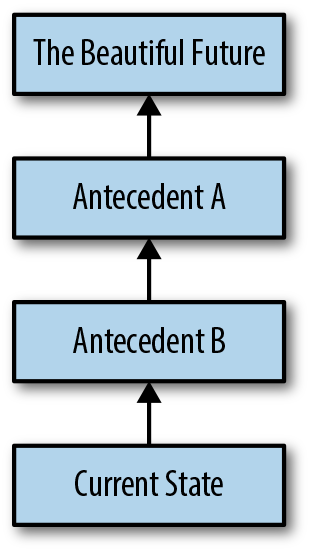

In any forecast (or backcast), there are two kinds of variables: dependent and independent. The values of dependent variables can be known only on the basis of the values of the independent variables. Dependent variables are the unknowns, the moving parts that you want to ascribe an outcome to in order to engineer a strategy toward making that outcome more probable. Independent variables are controlled by the strategist, and make up the levers that you can pull to try to change your outcome. Figure 3-2 shows the process.

Figure 3-2. The backcasting process

Necessary but Not Sufficient != Sufficient but Not Necessary

Be careful when assigning causation, as we discussed in Chapter 2. It seems reasonable to say “a necessary condition of having a baby is being pregnant.” But this is obviously false. So as always with antecedents in backcasting, and root cause analysis in diagnostics, beware of assumptions and biases creeping in.

Here are the steps in the backcasting process:

-

With your architecture, strategy, and product teams together, create a simple vision of the Beautiful Future. Do not give consideration to today’s circumstances, or how achievable it might be, just where you want to be. Don’t edit yourself. This should be a concrete image, or a metric goal such that you can determine very decidedly whether you have achieved it or not. For example, it could be fairly direct, like “All our software releases are on time,” or “No customer finds a bug before we do,” or “Defects have been reduced to six sigma levels.” Those may not seem like the realm of the strategist, but they are the realm of the CTO and development executives. And often you’ll have “get well” strategies. But these are examples. A more complex future vision might be about a legacy system replacement with a new, modern system. How does the team know when they’re done? How about “when they cut the power cord on the existing legacy system.” That’s an image, it’s concrete, and you can quickly see how a whole lot of things would need to have happened before that moment.

-

Hypothesize the immediately prior necessary state: those things that have to happen before the next moment can happen are called antecedents. They are the necessary condition for the next state to obtain. This is shown in Figure 3-2.

-

Then, once you have hypothesized the array of antecedents to the end state, you repeat the process to hypothesize the antecedent to that antecedent and so on, until you work your way back to the current state.

The current state is also called the status quo. It’s Latin for “the state in which” we find ourselves today. It’s the set of present affairs across people, process, and technology.

When you are performing this tracing back, keep in mind what would have to change with people, processes, and technology in each of the three steps. You cannot typically change one of those elements without incurring at least some impact on the others. Thinking of only one of these categories will result in myopia, and a failed strategy.

-

Next, consider the consequent. A basic statement in propositional logic has three parts: the hypothesis, the consequent, and the logical connector between the two. It looks like this:

P ⇒ Q

and means, “If P, then Q.”

What you’re looking for here is that true premises can never produce a false consequence, which means it’s logically valid. But a hypothesis is a premise, not a statement of fact. So it’s easy to get into trouble and assign as consequents things that don’t follow.

The consequent does not necessarily mean the consequence as it does colloquially, as in, “This directly causes that.” The consequent here should be the logical conclusion that necessarily follows, as an implication, as in “If Mister Boy is a cat, Mister Boy is a mammal.” As we’ve been cautioning, people in business meetings are not typically rigorous about this sort of reasoning. It is tempting to say, “If Mister Boy is a cat, Mister Boy is adorable,” but this is not a necessary consequent.

Worse, there are many absurd-sounding statements that are logically valid, but still nonsense, because you’re dealing with a hypothetical proposition. For example:

If pigs can fly, then I should wash my car on Tuesday.

Once you have worked out your vision, your antecedents, and your consequents, use your powers of analysis as described in Chapter 2) in probability assignment to tag each antecedent hypothesis with a probability, given the current state. If you’re pressed for time, you can guess. But going through the exercise and sketching it out as shown will point you to a set of conclusions about actions to take. Then you can prioritize them and get them in a project plan.

Summary

When creating a broad, multiyear strategy, you can apply these patterns in the order they are presented, starting with analysis: first consider MECE and create a Logic Tree (both described in Chapter 2), and create a set of hypotheses. Then, write your PESTEL analysis (see “PESTEL”) and conduct a Scenario Planning exercise (see “Scenario Planning”). You can then create your Futures Funnel (see “Futures Funnel”) diagram and perform a Backcasting (see “Backcasting”). That will then likely cause you to refine your analyses.

Of course, if you’re making a more specific, localized strategy for, say, changing out your database vendor, you can take the PESTEL analysis, for example, more lightly, or skip these, and move on to the next set of patterns: those for understanding the context of your industry.