Chapter 9. Decks

It is like a finger pointing away to the moon. Don’t concentrate on the finger or you will miss all that heavenly glory.

Bruce Lee, Enter the Dragon

In this brief chapter, we look at the different kinds of slide decks that come in handy for the strategist, as well as the structures and key elements you can use to make them.

Decks can be surprisingly useful as an architecture tool to draw pictures that communicate succinctly. They’re even more helpful if you present to customers a lot and need to have something that you can read from a screen.

But this chapter is more concerned with how you can take up all of the work that you’ve done throughout this book, and then pull it into decks that will make your data, insights, hypotheses, and overall strategic messages really soar.

Here we won’t talk about content—that was the first part of the book. We’ll just look at structure, assuming along the way that you’ve done the work from earlier patterns to populate the content as you need to.

Ghost Deck

The Ghost Deck is also called a Blank Deck. It’s a special way of making an initial deck that has a certain purpose. It’s a wireframe. There’s no audience but you and your management team, which you’ll subsequently work with to fill in the details of the simple narrative. The Ghost Deck is a storyboard made for creating a movie: you’re making sure you have figured out what all the important shots are before incurring the major expense of shooting them.

Say you need to make a big Ask Deck (see “Ask Deck”, or propose an initiative, fulfill the boss’s request to make a “get well” plan, or illustrate the story of what should be done. You need to craft the story itself without knowing all the data. You need to make sure that you have written an outline before you do any of the work, as we did in elementary school composition class.

The Critical Difference Between a Ghost Deck and an Outline

Let’s be clear on this important distinction. If, when you go to make an argument for something, you first write out the structure of what you want to say with no content in it, making sure that your argument has strong bones, as our teachers in grade school told us to do, then that is called an outline. If, on the other hand, you do the identical thing in PowerPoint and work for McKinsey and get paid $400 per hour to do it, then that is entirely different and is called making a Ghost Deck. The differences can be subtle, so please try hard to keep them straight.

Ghost Decks help you when you have three or four colleagues, maybe on your team or a cross-functional set of leaders, and you each have different perspectives on the situation. If you need to make a deck for the board, and you’ve got the tech person and the strategy person and the boss and the product person all there, it would be imposssible to open up PowerPoint and start typing a good deck from the first word.

-

Make an outline on a whiteboard or some nondeck surface. You need to stay at surface level and go one inch deep across the whole football field first.

-

Write only the headline for all the slides in the deck. Look at them to make sure they still make sense. Back in composition class, we all called this the “topic sentence”—it’s the claim you’re making. Make sure the headlines have rhetorical punch.

-

Once you’ve written all the headlines, review them, making sure they are impactful, make a bold claim, and build together, as we learned in “Dramatic Structure” and “Ars Rhetorica”.

-

Now you can assign someone to go get the research and write up the actual content in stages, make the charts and graphs, and write up the bullet points that prove the headline.

-

Have that helper send you the work in stages for frequent shoulder checks and revisions (or maybe it’s you playing both roles, and that’s fine too).

The guide I use for structuring a Ghost Deck is this: if your audience could believe everything that you say only by reading your headlines, they would have the entire story and wouldn’t need to read the body of the slides at all. Be disciplined enough that the body of the slides you are making is packed with facts backing up your headline claims. The bodies are all data, data, data. The headlines are all bold rhetorical claims.

Here’s a key to this pattern, as I see it anyway: most people treat headlines as these passive summaries that are a weak restating of whatever content they dumped into the deck. We, however, treat headlines as audacious, eye-popping claims like “Our company should buy company Y” or “We should get out of the coffee business and into the paperclip business” or “We must move the data center to the cloud within two years” or whatever that part of the argument is about. The point is that you’re putting a stake in the ground, advancing the argument, and not ever writing tepid generalizations like “The Plan.”

The advantage is obvious: you get to adjust the thrust of your argument and make changes to the main hypotheses you’re presenting before investing a lot of work in substantiating them, making beautiful charts, and so forth. I suppose you could think of this metaphorically as creating a backlog for yourself in the form of slide headlines.

If you’re working with a cross-functional group to make the deck, this can be a good way to align quickly with them without too much fuss and agree on the message you’re composing. This is valuable, because otherwise it could look like a Frankenstein’s monster all patched together with different styles and depths. And it wouldn’t be MECE, which would weaken it and take precious time to straighten out.

The big thing about Ghost Decks is that they are very helpful in maximizing your efficiency, organizational clarity, and impact of your eventual deck. You’re making the wireframe, the storyboard, first. Then you’re making sure that it makes sense at the wireframe level. Then you substantiate it in a separate step. I love Ghost Decks and use them every time I make a deck because the bang-for-the-buck ratio with them is terrific.

Ask Deck

The Ask Deck is the deck you use when you need to ask an executive to give you a big bucket of someone else’s money to go do your project.

By now, it should be clear that you can use the patterns we’ve discussed throughout this book as the building blocks for your local arguments within the Ask Deck.

When making an Ask Deck, first make a Ghost Deck, as described earlier. The basic structure is as follows.

The ask

The first slide says it all. You write your first slide last. Don’t write it first. Write it at the very end, only after you know everything. Structure it with a single sentence in the headline stating exactly what you want to do. Then, in the bullet points of the body, state a summary of all the things the executive would need to know to give an answer. Those are:

-

The current state is this: X, Y, Z dramatic data points.

-

Therefore, executive, you do this: X important project described in a single sentence with a name.

-

Here are the milestones so you know what you get along the way.

-

That will take X duration, require Y number of teams, and cost $X capex and $Y opex.

-

Here is the end state that you will have bought for that money: something awesome, and now the bad current state is over.

That is, if the executive believed everything you said, he wouldn’t have to look at the rest of the deck. So the entire rest of the deck is just a double-click of the first slide.

This one is totally counterintuitive. Most people wait for the big reveal of the number at the end: they think they’re being smart to write all the reasons why their project is so great and their thing is so important and they really want you to fund it, and then they reveal the number at the end. But you are not on the sales floor at a car dealership. This is a mistake. If you do this, I bet you dollars to donuts the CFO picks up his copy of your deck as you’re trying to present it and just starts flipping back to the end to read the bottom-line number. They’re grownups. They’re used to seeing big numbers. They know you’re not going to rebuild the legacy ecommerce system for $50,000. Give them the news up front so they can contextualize and adjust how hard they need to pay attention and to what. If they had the rough idea you were going to ask for something like $10M and you ask for $12M, then you’ll be having a different conversation with different levels of scrutiny and focus than if they walked into the conference room expecting a $1M ask and it’s a $5M ask. They will hear you better, and you’ll have a more productive, relevant conversation if you get all the bad news out of the way up front.

In fact, here is how I like to think about making these decks: write it all but the first slide, then write the One-Slider that says everything the executive needs to know. The test in my mind is that if he says “OK” on the first slide, you never need to look at the whole rest of the deck. You are not at a meeting to force executives to slog through your PowerPoint. You’re there to get a deal. They are punished enough by PowerPoint. If you can get a deal after one slide, fantastic. Let that be the goal, and drive what you pack into the first slide.

Imperil the hero

Employ the Shock and Awe and Book of Job techniques from “Dramatic Structure” to show the dire situation your company will be in without doing this thing. Here you’re making a statement to show how we are in bad shape or how there is a new super-exciting opportunity.

Let the data drive

Now let the data drive. Just be very methodical and objective, presenting the data that illustrates how any reasonable person would come to this same conclusion. This is the logical argument of Ars Rhetorica (see “Ars Rhetorica”). Examples:

-

X number of P1, P2, P3 contributed to Y amount of downtime YTD

-

Trends in P1, P2, P3 total up X% over past three years

-

60 items of technical debt (all detailed in the appendix)

-

12 most impactful things of kind X

Save the hero

Now that you’ve imperiled the hero, you have to offer the Path Forward. This is your vision of how you can claim the prize of the opportunity or how you can get out of this awful predicament.

To make sure that you have covered all the bases, your Path Forward should include details on all these elements:

-

The roadmap (see “Roadmap”).

-

How long will it take?

-

How much will it cost?

-

Who will do the work?

Make the plans for these elements first, and do it in detail. Then you refer back to them as you build out the project plan.

Appendix

Include an appendix, which might be longer than the deck itself. The appendix includes all charts, graphs, query results, and any substantiating data supporting the claims you made in your main deck. You will want these yourself later too when you won’t be able to remember the details.

Your main deck should be 12–15 slides. Executives will talk too much, and you will definitely never get further than 18 slides, and then you won’t have presented the whole force of your complete argument. But the appendix can be any length. You can include the appendix after the main deck in case the executives find themselves on a cross-Atlantic flight and want to vet your numbers.

Just use the patterns we’ve worked on. Using this structure has helped me a dozen times. With this structure, I’ve asked executives for millions and tens of millions of dollars to make sweeping changes to entire organizations or do multiyear heart surgery projects on mission-critical systems. I’ve never been told no. Not once. You can do it too.

Strategy Deck

The Strategy Deck is the simplest pattern of all. And the most complex. This is, ostensibly, the center of the book, yet it’s empty. That’s because, counterintuitively, when you’ve done all your homework, making the Strategy Deck will be practically a non-event. Here is how you do it:

-

Execute all the applicable creation patterns of this book while keeping in mind the analysis patterns along the way. See “Patterns Map”.

-

Collect your output from doing that.

-

Do a MergeSort of the output (see “MergeSort Meeting”) and make it into a deck with a smooth, comprehensive story using the communication patterns in this book.

Now you have a terrific strategy. That’s it. This is not intended to be flip. This is the case. The simplicity is lovely.

Roadmap

I have an existential map. It has “You Are Here” written all over it.

Steven Wright

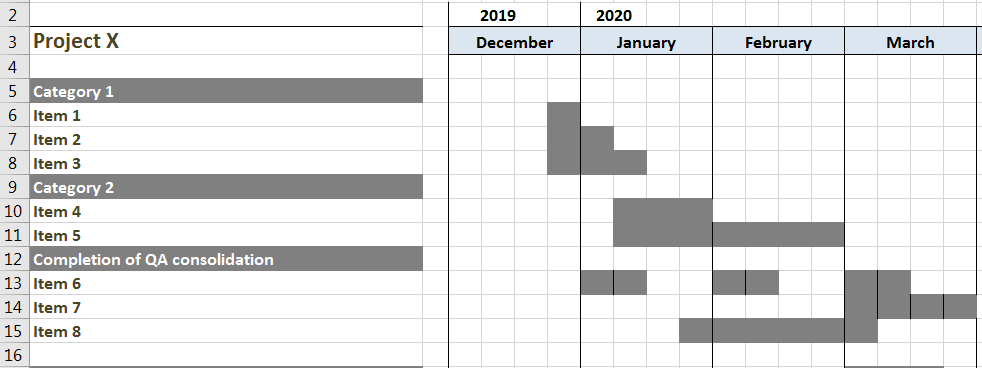

The Roadmap (see “Roadmap”) is generally for executive alignment and is of little use to dev teams. It shows in broad terms your milestone deliverables and is clear on indicating the end state. You’re stating less of a timeline here and more of the big building blocks, the meaningful work that you can release incrementally that together make up what you hope to achieve.

The teams won’t be interested in a view this broad, except maybe at the quarterly town hall meeting. It is of use to you, however, as the initiative planner: requiring yourself to state milestones like this makes you think in terms of deliverables (outcomes) that will be of benefit to your customer and can ship without dependencies on the rest of the program.

You should start at the end, and use a modified Backcasting (see “Backcasting”) technique to determine the right antecedent milestones.

You’ve seen these before. But Figure 9-1 shows an example. You want the roadmap to fit on a single slide.

If you’re presenting your overall roadmap to customers, I suppose you’re just putting quarterly releases on a timeline with the major releases, and that’s simpler. But if you’re embarking on a major initiative, stakeholders will need to see what they get when in more detail, how the planning and building blocks are expected to accompany this, and internal details such as when you plan to ramp up teams, when other teams are required to deliver their dependent part, and so forth, along with the milestones.

Once you have an approved roadmap, and you have done your costing and made a conceptual architecture, then make a Tactical Plan (see “Tactical Plan”). This is necessary to estimate durations, and to figure out how much can be done in parallel versus what aspects must be done in serial. That is necessary to determine your Directional Costing (see “Directional Costing”), which you need to make an Ask Deck (see “Ask Deck”). It’s all of a piece.

Figure 9-1. The initiative roadmap

Tactical Plan

The point of the Tactical Plan is to say, more as a reminder than anything, that the strategy work cannot stop here. This is only the beginning, the commencement of the strategy work. Stopping at this point will have achieved nothing.

You must turn your strategy, once approved, into a Tactical Plan. Remember the words of Sun Tzu: “Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.”

This can happen in two steps (see Figure 9-2). The first is that you figure out only the durations. Resist the temptation to put hard dates on the plan at first, but then you’ll need to do that as a second step. If you start with dates, you’ll get a worse estimate of timelines.

Figure 9-2. The basic Tactical Plan

Of course, there are many management books, courses, certificates, and software programs devoted to making great project plans, and you’ve surely participated in many of them. I include this pattern here mostly for completeness, and to suggest that making a preliminary Tactical Plan in this way forces you to think through everything: you can’t get a good idea of the project to propose in your Strategy Deck (see “Strategy Deck”) if you don’t do this step.

MergeSort Meeting

The MergeSort planning method is a novel way of working through plan-making meetings for managers that I made up and use on occasion. It works great if you, like I am, are a huge fan of making lists, as discussed in Chapter 2.

You use this method to solve problems when you are at the early stage of planning a large project. You have a mountain of brainstorming work you’ve done, or a Strategy Deck or set of ideas on lists you’ve been building, and you need to turn it into a plan. You want everyone’s ideas in a quick, unbiased fashion.

When the time comes to make a plan, I like to get everyone’s independent ideas. This could be a “get well” plan or the yearly strategy; anytime you want to brainstorm with your team, you can use this method to prevent groupthink from taking over.

You might be familiar with the MergeSort algorithm, invented in the 1940s by John von Neumann. It’s a way of sorting elements in an array as opposed to BubbleSort, QuickSort, and others. The basic implementation of MergeSort works kind of like this:

-

Take an unsorted list. Recursively divide it into sublists, which are trivially sorted.

-

Repeatedly merge these sublists back up the call chain to produce new, sorted, combined lists until only one list remains. This will be the sorted list.

There are different ways to implement it, and there’s a terrific animation of the process on Wikipedia. But for our purposes, we’re using it as a metaphor to help you create your tactical plan.

I use MergeSort as a keyword with my team, like a shorthand for this process. Here’s how to do it:

-

Call a MergeSort meeting to make your plan, and make sure you clearly state the scope of what you need to build the plan for.

-

Have everyone make a separate list of lists, perhaps categories focusing on different aspects of the project such as “business,” “data,” “infrastructure,” or whatever are the main categories of your project as outer headers. Use a common set of categories such as people/process/technology for the inner loop’s set of headers.

-

Give everyone time to populate their lists of lists independently. You will generate a lot more ideas this way, and be more inclusive of shy people in the group and flatten out the louder voices.

-

Bring the raw material lists together in your MergeSort operation meeting.

-

Now you have a single merged list and you want to prioritize it. So use some other lenses you’ve learned in this book (like making a 2×2 matrix for likelihood/impact) to help prioritize things.

-

The project manager takes over the meeting to take the now single, merged, prioritized list of lists and assign who does what by when into a spreadsheet.

-

Now you’ve got a really comprehensive plan that the PM can track and someone can go execute.

Maybe this is too idiomatic, but I like it. It seems to work when called for, and I honestly hope you find it useful.

As you have seen in this chapter, your Tactical Plan generally will look like ones you’ve seen a lot before. But strategy without execution is just like the kids in the backyard making neat rules for the fort with no bearing on reality. A clear Tactical Plan is key to successfully carrying out any strategy.