CHAPTER 8

The Programmed Machine

In the automobile business, uncertainty is the biggest enemy.

—Thomas Murphy, CEO of General Motors50

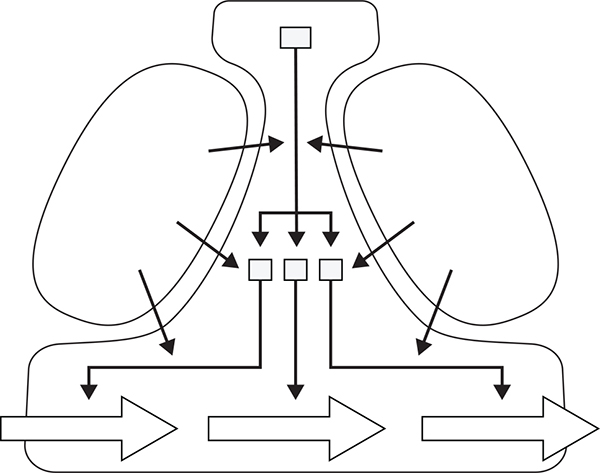

Now for something completely different, from the simplest structure to the most elaborate (but not the most complex). The logo of the original version of this book is used for the Programmed Machine because, as noted in Chapter 2, it portrays the conventional, hierarchical view of the organization.

(Logo for the Programmed Machine)

Programmed Machines love hierarchy, order, control, systems, and especially rules, rules, rules. Everything conceivable is programmed, sometimes even the customers. (Have you cleared your tray at a fast-food franchise recently?) All this so that the organization can run as smoothly as a machine. This is why that CEO at GM claimed that uncertainty is the biggest enemy. (Go tell that to an entrepreneur, for whom uncertainty can be the biggest friend. After all, that’s how Personal Enterprises beat the Programmed Machines.)

No sport comes close to North American football for its sharp divisions of labor and the extent of its programming. Rules or standards specify who is allowed to hold the ball, catch it, and kick it. Look at the formation on the field, not to mention the cheerleaders on the side: everybody is so carefully lined up. This is not yacht racing, believe me, let alone hockey. Even hierarchy is built right in: the quarterback calls the play, possibly radioed in from the coach, by number no less, and all the players respond accordingly. A sport made to measure for Frederick Taylor’s scientific management!

Basic Structure of the Programmed Machine

Every machine has its parts, each specialized to do its bit for the carefully designed whole. (Consider the Administrative Assistant to the Assistant Secretary for Administration.) As Yuval Hariri wrote in his book Sapiens: “In bureaucracy, things must be kept apart. There is one drawer for [purchasing, another for manufacturing, a third for selling]. Otherwise, how can you find anything? Things that belong in more than one drawer . . . are a terrible headache.”51

In the operating core of the machine organization, jobs are made as simple, specialized, and repetitive as possible, to be done with a minimum of training—often hours, even minutes. (We will come back to football as an exception later.) Coordination across these jobs is achieved especially by the standardization of work, supported by the standardization of the outputs. (“Turn that hamburger patty over in 17 seconds.”) This enables the bottom managers to supervise a great many workers. Here is a description of a typical Programmed Machine:

All operations were carried out according to a predetermined plan. . . . Directions were numerous and explicit, and the work to be done was structured according to task and specialty [with “extensive division of labor”]. The performance of subordinates was closely and efficiently supervised.52

This is the temple corporation in ancient Mesopotamia. The Programmed Machine has been around a long time!

If the Personal Enterprise works like a hub, around its chief, then the Programmed Machine often works like a chain, upon a chain, as shown in the logo figure. At the base is the horizontal chain of work that passes sequentially from one link to the next (as in an automobile assembly line). And laid over this is the vertical chain of command, as the managers are stacked up—upon each link and upon each other.

To the left side of the line hierarchy sits the analytical staff who design and control the standards that program the cogs of the machine— people with titles such as work-study analyst, production scheduler, planner, budgeter, and accountant. Hence the sharpest division of labor in the machine organization is found between the operators who do the work, the managers who administer it, and the analysts who design it. Nevertheless, the technostructure emerges as a key part of this organization. To the line managers may be delegated the formal authority, but to the staff analysts goes the informal power that drives the behavior of everyone else, including the line managers themselves, who also have to adhere to the rules.

When I was president of this big corporation, we lived in a small Ohio town, where the main plant was located. The corporation specified who you could socialize with, and on what level. (His wife interjects: Who were the wives you could play bridge with.) In a small town they didn’t have to keep check on you. Everybody knew. There are certain sets of rules.53

In effect, therefore, the machine organization is selectively decentralized, officially to the line managers but substantially to the staff analysts—which gives rise to political games played between line and staff.

On the right side of the figure is the support staff, not powerful so much as abundant, to help maintain the smooth running of the machine—everything from the cafeteria that feeds the people to the legal counsel that handles the lawsuits (of which there can be many). The proliferation of the support staff is partially explained by the obsession with control in these organizations. Many of the staff services could be purchased from outside suppliers, but that would expose the organization to the uncertainties of the marketplace. So the inclination has been to make rather than buy—in other words, envelope as many of the support services as it can within its own boundaries. (Chapter 20 discusses recent tendencies in the opposite direction.)

Conditions and Kinds of Programmed Machines

Programmed Machines thrive in environments that are simple and stable. The work in complex environments can’t be rationalized into simple tasks, while that in dynamic environments can’t be predicted, made repetitive, and hence standardized. Thus, don’t look for this form of organization in advertising agencies or film companies, but in retailing and fast-moving consumer goods firms (e.g., pens, toothpaste), namely in mass production and mass services, especially those that pursue a strategy of “cost leadership”—that is, low price.54

In addition, this form is frequently found in mature organizations, large enough to have the volume of operating work needed for repetition and standardization, and old enough to have settled on the standards they wish to use. These are the organizations that have seen it all before and established procedures to deal with it. Hence, as Personal Enterprises age and grow beyond the control of their founders, many metamorphose into the machine form—at least those that have been functioning in simple environments. And while such a Personal Enterprises may have thrived in a dynamic environment (uncertainty being its best friend), after this kind of transition, the machine form will do what it can to stabilize that environment for the sake of its own programming—for example, develop long-term contracts with suppliers and establish cartels with competitors.

Control enters this picture in other ways, too. Organizations in the business of control tend to use the machine form: banks that have to protect people’s money, prisons that have to hold inmates, airlines that have to land their passengers safely. As one joke goes, airlines “will soon be moving to a new flight crew, one pilot and a dog. The pilot is there to feed the dog, and the dog is there to bite the pilot if he touches anything.”55

External control is another condition that drives organizations to the Programmed Machine, because, as discussed in Chapter 6, it acts to centralize and formalize their practices. An owner who wishes to maintain control of a business without managing it appoints a CEO who is held responsible for achieving tight standards of performance. This CEO, in turn, imposes plans and targets down the managerial hierarchy to meet these standards. Taking a company public on the stock market can have the same effect: the market analysts expect a steady growth of earnings. Government departments are likewise driven toward the machine form because politicians and senior civil servants don’t like surprises and so encourage the proliferation of rules to avoid them.

But while some Programmed Machines may be the instruments of external influencers, others are closed systems that seek to block out as much outside influence as possible. Of course, no organization can ever be completely closed. But some machine organizations do come remarkably close—for example, businesses with monopoly positions in their markets. In this regard, don’t forget the Communist regimes of the twentieth century, which functioned as massive, closed Programmed Machines. (Ironically, the Cold War pitted the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe against the capitalist corporations of the globalized world, yet structurally, were they that different? As James Worthy, an American executive and writer, commented: “Scientific management had its fullest flowering, not in America, but in Soviet Russia.”56)

Interestingly enough, shifting between being the instrument of an outsider and the closed system of the insiders can be rather easy, because there is no need to change the structure. With formal authority so concentrated at the top of the hierarchy, just bring in a new chief and carry on. (Bring in a new chief in a Personal Enterprise, and everything can be up for grabs.) And don’t think this is restricted to business. Many a machine-like NGO, even a whole government taken over by a new political party, has so carried on, perhaps with a new agenda but hardly missing a beat.

Pros and Cons of the Programmed Machine

You don’t want your Amazon package delivered to the house next door, or your 8:00 a.m. hotel wake-up call coming at 8:05, any more than you want a guard on your football team to catch a pass from the quarterback. There are rules, after all. When an integrated set of simple tasks must be performed precisely, predictably, and consistently, at least by animate human beings rather than inanimate machines, the Programmed Machine is unbeatable.

And, for the same reason, sometimes unbearable too. People can be treated as mechanical parts, but they never are. Nor are they economic things: treating an employee as a human resource is like treating a cow as a sirloin steak. I am not a human resource, thank you, nor a human asset or human capital. I am a human being.

Bureaucracy for Better and for Worse

As noted, the word bureaucracy is often associated with organizations that function like machines. The term was popularized, innocently enough, by the renowned German sociologist Max Weber, early in the twentieth century, as a neutral, technical term for the kind of organizations we are discussing in this chapter. Weber, in fact, used the word machine with regard to its precision and speed: “The fully developed bureaucratic mechanism compares with other organizations exactly as does the machine with the non-mechanical modes of production.”57

But bureaucracy has also taken on a pejorative meaning, as the bad guy of the organizational world, obsessed with control: the executives control the managers, the managers control the workers, the workers control the customers, and the analysts control them all.58 The planning manager of a British company once remarked that “through the control process, we can stop managers falling in love with their businesses.” Should they hate their businesses instead? Michel Crozier concluded in his renowned study of two French government bureaucracies that everyone is treated more or less equally in these organizations because all are controlled by the same overwhelming set of rules.59 (Like Crozier, it is remarkable how many people rose to prominence in the literature of management by writing about the dysfunctions of machinelike organizations: Mayo, Roethlisberger, Argyris, Bennis, Likert, McGregor, Worthy, and others.)

Today we also use the word bureaucracy for government in general, even referring to civil servants as bureaucrats—sometimes with the same disparaging undertone. Of course, not all of the public sector is machine bureaucratic (as we shall discuss later), while no few corporations in the private sector are just that. (Read the Dilbert comic strip about bureaucracy in business.)

Let’s consider the problems of this form of organization on three levels in the hierarchy.

Alienation in the Operating Core

Frederick Taylor was fond of saying, “In the past the man has been first. In the future, the system must be first.” Prophetic words indeed. For many people, the Programmed Machine is not a happy place to work, especially in its operating core. To return to James Worthy: Taylor’s view to remove “all possible brain work” from the shop floor also removed all possible initiative from the people who worked there: The “machine has no will of its own. Its parts have no urge to independent action. Thinking, direction—even purpose—must be provided from outside or above.” This had the “consequence of destroying the meaning of work itself,” which has been “fantastically wasteful for industry and society,” resulting in “excessive absenteeism, high worker turnover, sloppy workmanship, costly strikes, even outright sabotage.”60 Wow! And from a corporate executive, no less.

Bear in mind that such criticism has often come from people who are writing, not about their own work, but for the legions of workers made miserable by hyperprogrammed work. For those workers who relish order and predictability, however, the machine organization can be just fine, thank you. Here is how a checker in a supermarket described her work (as quoted in Studs Terkel’s wonderful book Working):

They put down their groceries. I got my hips pushin’ on the button and it rolls around on the counter. When I feel I have enough groceries in front of me, I let go of my hip. I’m just moving—the hips, the hand, and the register, the hips, the hand, and the register. . . . (As she demonstrates, her hands and hips move in the manner of an oriental dancer.) You just keep going, one, two, one, two. If you’ve got that rhythm, you’re a fast checker.61

Conflict Bumped up the Hierarchy

The operating core of the machine organization is designed to get things done efficiently, not to deal with alienation and conflict. Hence many human problems that arise in the operations get bumped up the hierarchy, to the managerial middle—straight into the system of silos that hardly encourages the use of mutual adjustment necessary to deal with them. Too often, the consequence is more conflictive heat than cooperative light.

And so, these conflicts, together with others created by the silos, can get bumped further up the hierarchy, through the slabs, until the buck stops at the top, where the silos finally come together. But can a management above deal with the problems below—ones with which they may lack direct contact?

Disconnect at the “Top”

The answer for the Programmed Machine, once again, is supposed to lie in a system, specifically the Management Information System (MIS). It hardens the data generated on the ground, by aggregating it as it mounts the hierarchy, into reports convenient for busy managers to read.

Sales are falling in Indonesia? Tell the manager there to lift them up. But why are they falling? Maybe because the products designed in Iowa are not suited to Indonesian consumers. But the MIS says nothing about that; you have to talk to the customers there to find out. But from a seventy-seventh floor office in New York? Of course, the managers in Indonesia may know why, but where in the MIS are they to enter this information for their bosses at the U.S. HQ?

As Michel Crozier has described the machine organization, “the power of decision . . . tends to be located in a blind spot”: “Decisions must be made by people who have no direct knowledge of the field . . . and who must rely on the information given them by subordinates who may have a subjective interest in distorting the data.”62 Or by an MIS that not only aggregates out the necessary details, but also takes time to get its aggregated reports to the management—while more agile competitors may be running off with the customers.

Hard information may help to identify problems, but soft information is necessary to diagnose and resolve them. Lacking that, however, senior managers in the machine organization fall back on the tried if untrue: they tighten the controls, in other words, pour oil on the fire. If, instead, they use direct supervision, they risk being accused of micromanaging: “This is not your Personal Enterprise; respect the hierarchy; focus on the big picture.”

To paint a big picture requires mastery of the details, which look awfully hazy from a seventy-seventh floor office. As a result, machine organizations mostly come up with small pictures—marginal adaptations of their existing strategies, or else me-too copies of the strategies of other organizations.

We can call the organizations that do this the local producers, of established industry recipes, distinguished by where they execute them, not how.63 It is certainly efficient to program some standard strategy into your own organization, which is why it is so common. Just have a look at the telephone companies and post offices in different countries, likewise your local grocery store and fitness center.

The machine organization has a way around this. Use Strategic Planning, one of the most popular techniques of all: follow the directions to program the strategy. Unfortunately, Strategic Planning has turned out to be an oxymoron (see box).64

Coming to Terms with Our Machines

We talk incessantly about changing our organizations, especially the machine ones. Is this always necessary? Machines are designed to do specific things. The furnace in our home works very well where it sits, thank you, blowing warm air. I was trained as a mechanical engineer: I suppose I could adapt it to work as a hair dryer. But it’s a lot easier to go out and buy one of those instead. By the same token, why change a Programmed Machine to do what it was not designed to do, instead of concentrating on fine tuning what it does well. Efficiency is its forte, not innovation. An organization cannot put blinders on its people and then expect peripheral vision.

Generations of planners, consultants, reengineers, and writers have tried to convince us that the Programmed Machine is the default mode of organizing—the all-time one best way. I would guess that 80 percent of everything ever written about fixing organizations has been written about machine organizations, although not recognized as such, whether to tighten those controls and plan everything in sight, or else cope with the consequences of these controls and plans by bringing in that maintenance crew for the human machinery.

I’m not one for “five easy steps” to do anything in organizations, but I make an exception with this box for any chief determined to fix his or her organization, quickly.

All four forms of organizations have their pros as well as their cons. The machine organization may not be the one best way to organize, but it is one important way. So long as we demand inexpensive, mass-produced products and services, which can be provided more efficiently by people than by actual machines, the Programmed Machine will remain with us—with all its faults.

As you may have gathered, this is not where I prefer to work. (That’s coming next.) But I do appreciate these machines for flying to conferences and printing books. I cannot live without them even though I choose not to work within them. And like most everyone, I had better not kid myself into thinking that other people are the bureaucrats. We are all the bureaucrats—you and I—when insisting on adherence to the rules for the sake of some order we wish to preserve.