CHAPTER 20

Organizations Outward Bound

The term outward bound was originally used to describe ships departing their home port for foreign destinations. Later it came to be associated with an NGO that provides youth with adventures in nature. Here it can be used to describe what many organizations have been doing in recent years.

Bound has two quite opposite meanings. Besides that of going somewhere else—opening up—is that of closing in, “being restricted to or by a place or situation” (Oxford English Dictionary). This chapter discusses how organizations that used to be bound by their borders have in recent times gone outward bound.

Let’s go back to that seven-year-old’s question at the outset, about what is an organization, for example, an Apple. If you answer that it is the people who work for “Apple,” what if she asks about the guy sweeping the floors in one of their stores: “Is he an apple too?” “No, he’s on contract.” “Huh?” If she looks at your phone and asks: “If this is an apple, why aren’t those little things called apples instead of apps?” “Because Apple is a platform.” “Like the stage at a concert?”

The boundaries of many organizations have indeed become blurred in recent times, with contracts for cleaning going out and apps for connecting coming in. Many researchers and journalists have followed suit, by describing all this in ways that themselves are blurred. This chapter seeks to bring some clarity to this. I noted in Chapter 1 that the first version of this book was subtitled “A Synthesis of the Research,” whereas this version is meant to be a synthesis of my experiences. Except in this chapter, which offers a synthesis of what looks to be the most significant development in organization structuring in recent times.133

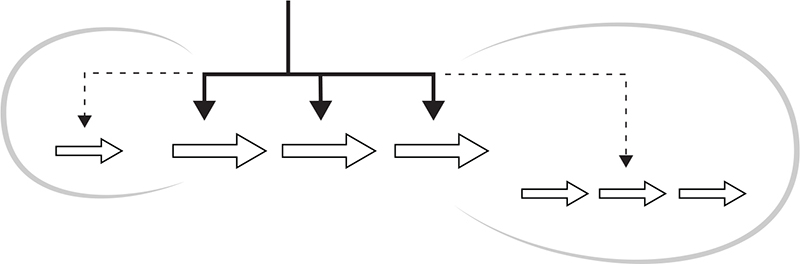

We begin by describing how inwardly bounded organizational structures used to be: sharp borders were maintained, even while pursuing strategies called diversification. Then, along came a variety of arrangements that have taken organizations outward bound. We discuss six: networking out, contracting to outsource, partnering to venture jointly, establishing a platform for others, affiliating for common purpose, and associating around a table.

If in the late twentieth century, the Project Pioneer became the favored structure—in fact, by breaking down the boundaries within organizations—then these arrangements that break down the boundaries across organizations have been having their full flowering in the twenty-first century. All sorts of walls have come tumbling down.

Bounded by Diversification and Vertical Integration

For much of the twentieth century, the most prominent strategies of large corporations were vertical integration and diversification, pursued within their traditional boundaries.

Vertical integration extended the chain of operations of the organization, to encompass suppliers at one end (upstream) and customers at the other (downstream), by bringing them inside its own boundaries. An automobile company might buy a supplier of its batteries, or create its own dealerships. Henry Ford pursued this strategy to an extreme: “To complete the vertical integration of his empire, he purchased a railroad, acquired control of 16 coal mines and about 700,000 . . . acres of timberland, built a sawmill, acquired a fleet of Great Lakes freighters to bring ore from his Lake Superior mines, and even bought a glassworks.”134

When it diversified, a company bought others in different businesses, and likewise brought them inside, or else developed new businesses internally, as did Honda, by exploiting its expertise in motors to produce a variety of other vehicles—outboard motors, lawnmowers, ATVs, and so on. Either way, the boundaries of these organizations usually remained sharply delineated, with the new activities reporting through its established hierarchy of authority. Under Henry Ford you were Ford. Period.

How this has changed!

Networking Outward

Networking is hardly new. In our institutional lives, like our personal ones, we have always networked to facilitate communication, externally as well as internally. What has changed in recent times, thanks to the new social media, is the reach of networking externally. Connecting with associates around the world can sometimes be easier than connecting with neighbors next door. At the end of their shift in Boston, a team of software engineers can transfer the work where they left off (asynchronously) to a team in Bangalore, which will continue the work until they transfer it back at the end of their shift, all with remarkable seamlessness.135

Networking need not be based on any formal structural arrangement; it can just happen, for the sake of coordination by mutual adjustment. In contrast, the other five arrangements of outward bound are somewhat formally structured—two by making use of contracts, another of rules, the last two of designated membership.

Contracting to Outsource

An organization’s boundaries begin to blur when it engages in outsourcing—the opposite of vertically integrating—as some activities previously done in-house are contracted to outside organizations or individuals. For example, most companies these days contract out the cleaning of their offices, and many engage executive search firms to help them find new managers. In these cases, the supplier is not in the organization, but not quite out of it either, because it supplies its services on a regular basis, under contract, for a negotiated period of time.

How about this for an example? Once, when visiting a factory, I was told that the workers in blue were employees of the company whereas those in green were not: they were doing similar work, but received their paychecks from another company. Talk about blurring the boundaries: this one was evident only in the color of the work clothes!

Some outsourcing has been around for a long time.136 Most every organization has always bought on contract, for example, legal services. And contractors in the construction industry have long used an extensive form of outsourcing. As their name suggests, they secure the contract to construct a building and then subcontract the activities—electrical, plumbing, scaffolding, and so forth—to a host of specialized companies. Not so different is a film company that decides what film to make and then engages independent directors, scriptwriters, actors, editors, and so on to make it.

If the recent wave of outsourcing has come partly in reaction to the excesses of vertical integration (Henry Ford–style), now the pendulum can have a tendency to swing the other way. It’s one thing for a retailer to contract out the maintenance of its stores, quite another to let go of, say, the sourcing of its merchandise (Amazon?). And while extensive contracting may work in the film business, it risks hollowing out the essence of some other organizations. Key here is to figure out what are the organization’s core competencies—those it cannot let go without being a viable operation, such as securing the contracts and choosing the subcontractors in those construction companies.137 Sometimes, however, an organization can be surprised by what turns out to be a core competence. Was this the case with Air Canada that developed a highly successful points program called Aeroplan, then spun it into a separate division, later sold it, and finally bought it back?

Outsourcing has, of course, hardly been restricted to business. In the plural sector, years ago my own university converted many of its administrative staff to contracts, which in my opinion has weakened its culture. And outsourcing has long been prominent in government, if not by that name. With so many services to provide, it has long used outside suppliers for much that could have been done inside. In fact, many NGOs exist to provide public services on contract—say, programs to feed the poor. More recently, the New Public Management (discussed in Chapter 14) may have been driving the outsourcing of public services to excess, perhaps like those American states that have outsourced prison services to private companies.

It is worth noting that outsourcing, and some of the other arrangements to be discussed, have been taking organizations toward the project structure, for the same reason as have the automating of their operations. With the shedding of some internal activities, more of their administrative work functioned as projects—for example, to negotiate external contracts instead of having to manage internal functions.

Partnering to Venture Jointly

Here the borders blur further, as independent organizations partner to design, develop, and/or market particular products or services. They venture jointly, and temporarily. For example, “an idea travels from innovation to commercialization through at least two different companies, with the different parties involved dividing the work of innovation.”138

The Smart Car was an interesting example of this in the automotive industry, resulting from a joint venture of Mercedes and Swatch, of all things. And the vaccine breakthrough in the COVID pandemic came from a joint venture of Pfizer with the husband and wife team of a small company.139 Watch a feature film today and you will likely see a whole list of “producers.”

Here again, the arrangement is hardly restricted to business. The label joint venture may be favored by business, but that of PPP (public-private partnership) is commonly used for joint ventures across two of the sectors. In fact, many that go by this label are really public-plural partnerships, while public-plural-private partnerships (not yet called PPPPs) are not uncommon, as when local governments, companies, and NGOs partner to reduce pollution in their city.

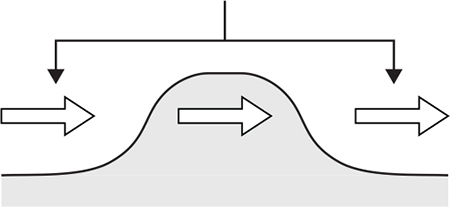

Offering a Platform for Others

The other face of outsourcing is what might be described as insourcing: an organization sets itself up as a platform for the particular use of outsiders. Coordination on the platform, between supplier and user, even between users who meet there, as on eBay, tends to be largely by mutual adjustment, but electronically.

Wikipedia is an archetypical example of the platform organization, as is open-source software. To use the words of Wikipedia about OSS: “the copyright holder grants users the right to use, study, change, and distribute the software and a source code to anyone and for any purpose.”

I am not an employee of Wikipedia, not even a member. (It has no members. On its website: “How do you become a member of Wikipedia? Just go for it!”) I am thus not inside Wikipedia, yet am I outside of it? I can go inside any time I like. How about now?

As I wrote this, I went in to Wikipedia and looked up “platform organization.” Here is what I got: “The page ‘Platform organization’ does not exist. You can ask for it to be created.” By myself, no less, so long as I follow some rules. (Facebook, another platform organization, found out what can happen when the rules are inadequate.) Imagine if I could do this with my supermarket: “I couldn’t find tiger shrimp in your seafood list, so I added it. I will come by tomorrow to pick some up.”

Wikipedia is a plural-sector organization with no owner—it’s neither private property nor public property, but common property, available to all, like the ocean. (It funds itself by soliciting donations from its users.) Facebook, in contrast, is the private property of its shareholders, as are many other platform organizations. Yet its influence on our social discourse has caused it to be treated like common property, almost public property. More blurring of the traditional boundaries.

How to define the presence or absence of the boundaries of an organization like Wikipedia? As outlined in what Seidel and Stewart call the “new community architecture,” or C-form, these plural-sector platforms have “(1) fluid, informal peripheral boundaries of membership; (2) significant incorporation of voluntary labor; (3) information-based product output; and (4) significantly open sharing of knowledge.”140

On the more conventionally commercial side, some years ago American Airlines joint ventured with IBM to create SABRE, a platform that enabled “tens of thousands of travel agents and others . . . [to be] perfectly coordinated in . . . reservations for the flights, hotels and car rentals that are listed there.” And, of course, Apple created the iPhone as a platform on which all kinds of organizations can offer their apps.141

Just as the gentleman in Molière’s famous play discovered that he was speaking prose, so too are we discovering that we have been using such platforms for a long time—for example, food markets where farmers rent space to find their customers and stock markets where investors go to buy and sell their stocks.142 And think about all the doctors who have long viewed hospitals as platforms where they practice their profession. Some companies have, in fact, sought to reframe their business as a platform for their own benefit. Uber, for example, prefers to be seen as a platform for drivers to sign up and find people to shuttle around. Funny, because I thought it was a taxi service that found an outsourcing way to keep its drivers at arm’s length.

Affiliating for Common Purpose

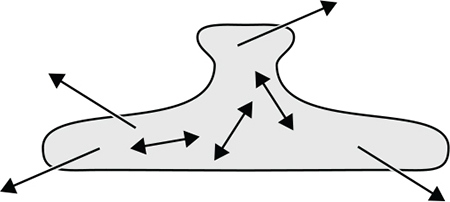

Affiliating is a kind of inserving (in contrast to outsourcing), where a group of organizations join together to provide themselves with one or more common functions. Thus do hospitals sometimes affiliate to negotiate with suppliers for better prices. (Together, these Professional Assemblies form an assembly.) Likewise, businesses create their Chambers of Commerce, sometimes to promote local tourism. (Ahrne and Brunsson have labeled these meta-organizations.143)

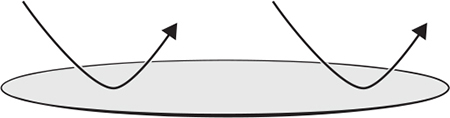

Affiliating is similar to platforming, except that here the users create the platform for themselves, as members, with no single one in charge. In other words, they affiliate, but don’t integrate, since each member maintains full independence. At the center of the assembly may be a small staff to hold it together, typically headed by someone in a member organization elected to a limited term of office. Compare the example used earlier of the small national accounting firms that affiliate to provide foreign services to each other with the global accounting firms, incorporated as single organizations, and so structured closer to the Divisional Form. Hence, the figure above depicts affiliation in the form of a donut, with the substance in the ring, not at the center.

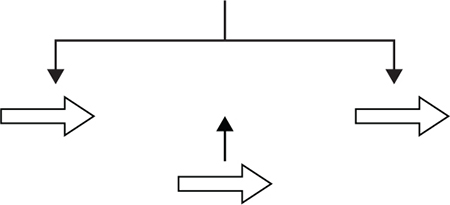

Associating around a Table

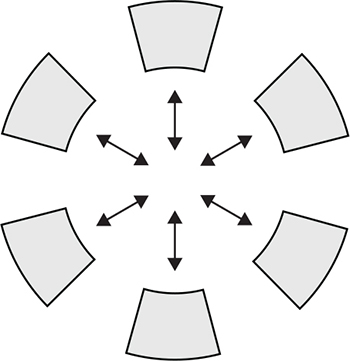

What we are calling associating may appear to be similar to affiliating, but the distinction is worth making. It is looser than contracting, venturing, platforming, and affiliating, but still an arrangement of organizations outward bound. Here, organizations combine for convenience, with an established membership, to associate for common concerns rather than affiliate for specific functions. The figure above depicts the associates, symbolically but often literally, sitting at a round table, where they meet periodically to discuss interests they share in common. Look for much of this in diplomacy—for example, in the G20 and G7, compared with NATO, which is an affiliation with a military function.

Popular terms such as consortium, chamber, alliance, and assembly may describe these associations, although some, as we have seen, are used for affiliations as well. Do the trade associations in industries discuss common concerns, or lobby for common causes? Often both. How about a few big competitors that get together periodically “just to chat, mind you”—whereas this association turns out to be a front for the affiliates of a cartel?

The Forms Outward Bound

All six arrangements can be found in any of the forms and hybrids, although more in some, less in others.

Perhaps less in the Programmed Machines, Personal Enterprises, and Community Ships: being predisposed to maintaining control, they can be disinclined to open their boundaries beyond some outsourcing and associating. Perhaps more in the Project Pioneers that are naturally open and flexible, not only to take themselves outward bound with all these arrangements, but also to welcome other organizations inward bound—for example, by including outside employees on their own teams.

Likewise we should expect to find a good deal of all these arrangements in the Professional Assemblies. Their borders tend to be wide open, with many of their professionals inclined to network and joint venture, affiliate, and associate right and left, locally and globally. Notice how often media interviews of university professors happen when they are travelling abroad. Universities themselves also reach out in all kinds of ways—for instance, when they venture to create joint degree programs (see box).

I hope that this discussion will encourage you to go outward bound, in your own life as well as in and across your organizations, to address the puzzling puzzles that have been plaguing us for centuries. In the final chapter, we consider how to help make this happen.