CHAPTER 14

The Divisional Form

Let’s say you make canoes in Canada. Why not kayaks? Expand your market with many of the same materials, processes, and customers. Well, then, why not paddles? Different materials but the same customers. And how about docks? After all, some of these customers buy docks. Next thing you know, you’re making icebreakers. Uh oh!

This is the road to diversification—from different products to different businesses—taken not only by many companies but also by organizations in the plural and public sectors. Diversification starts with related products or services (kayaks after canoes) and ends with ones that are unrelated (ice breakers) in what is called a conglomerate. For years, big business, especially in America, has gone through waves of conglomeration followed by consolidation (as we shall discuss).

Diversification leads to divisionalization: a company operating in separate businesses creates separate units—usually called divisions—to deal with each, subject to oversight (in both senses, as we shall see) by a headquarters that controls them through the enforcement of standards of performance. How much autonomy they get depends on how different they are from each other: we might expect the icebreaker division to have more autonomy than the kayak division.

Here, then, we have the Divisional Form, also called federation in some nations and NGOs. Canada is a federation of provinces, for instance, and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies has almost two hundred branches in countries around the world.99 Since the Divisional Form has been most widely used in business, much of the discussion that follows will rely on business examples and experience, until we come to the final section of the chapter, which considers its use in these other sectors.

Expanding Out, Acquiring In

Diversification is associated with growth and aging. As an organization grows, it may run out of opportunities to expand in its traditional business, and as it ages, its managers may seek opportunities beyond the established business. It is thus hardly coincidental that so many large established corporations end up with some variant of the Divisional Form.

From canoes to kayaks is an example of a company expanding out— by developing from one business to another. When a company does a great deal of this, we might refer to it as engaging in crystalline diversification, since it grows like a crystal, as did 3M in the US (from sandpaper to all sorts of bonding and coating products) and Panasonic in Japan (which began with lightbulb sockets and now produces a wide range of consumer electronics). With their steady stream of innovations, these companies can also be seen as Project Pioneers.

If an organization can expand out, it can also acquire in, by purchasing other companies. Sometimes this is referred to as a merger, although many such “mergers” amount to acquisitions, as the bigger company gobbles up the smaller one.

Acquisitions that happen within the same industry—say, when one brewery acquires another—are normally thought of as related diversification. With regard to strategy maybe, but with regard to structure, there is no such thing as a related acquisition. The very next day, the only thing those two breweries have in common is the thought that they both brew beer. They have no brands in common, no brewing in common, no managers in common, no culture in common (in their beers as well as in their structures). These have to be grown together, consolidated, and that may be easier for the cultures of their beers than for the cultures of their organizations. It can take years to get the people to function together harmoniously. And when they really do merge, as relative equals, this can be more difficult still, because there is no one authority to force them to cooperate: no queen CEO, so to speak (see box, of a story told to me by a beekeeper).

The opposite can be seen with internal diversification. Much as a child gradually grows apart from its parents, yet never completely, so too a business tends to remain connected to the others from which it was spun off. After all, it grew out of the same culture.

A brewery can easily add cherry beer to its product line: put in the flavor, print new labels, and market accordingly, most of this with the same employees. But if it wishes to turn this into a Flavored Beer Division—cherry, banana, rosewater, whatever—these activities will have to be grown apart—weaned off the mother beer, so to speak. Yet the bond never quite breaks, because the personal relationships remain. Betty in banana beer can call her old buddy at headquarters: “Hey Bruce, can you help me with this problem?” whereas Arthur in the acquired beer company has no buddy at HQ.

Stages in the Transition to the Divisional Form

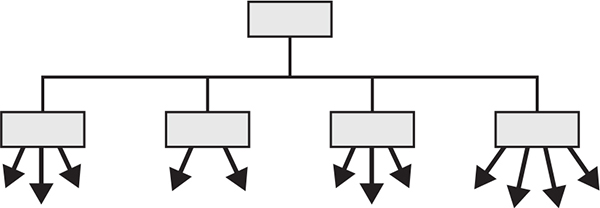

In business the transition to the Divisional Form is commonly described in four stages.100

• Stage 1: Vertical Integration. Let’s start with a company that is fully integrated along its chain of operations—say, from purchasing to production to marketing to sales—with coordination between these managed centrally, through the standardization of work and outputs. In this first stage, known as vertical integration (although, typically shown horizontally, along the operating chain), the company acquires other companies, or develops these activities internally, at either end of its operations. Our canoe company buys a manufacturer of Kevlar, or a chain of sporting goods stores. There may be a need to integrate the different cultures, but otherwise the structure remains functionally integrated.

• Stage 2: By-Product Diversification. As an integrated company seeks wider markets, it may decide to sell its intermediate products on the open market, in what is called by-product diversification. The canoe department might sell its yokes to other canoe companies. Similarly, an aluminum company could be selling by-product chemicals from its refining process or even excess cargo space in its transport vehicles. This introduces breaks in the operating chain—now the sales people who were selling canoes or aluminum ingot have to sell yokes or chemicals and space to new customers—but otherwise the structure remains intact.

• Stage 3: Related-Product Diversification. The next stage begins when the by-products sales become as important as those of the original products. Now our canoe company finds itself seriously in the yoke business, and so dedicates a division to doing that, with somewhat greater autonomy.

• Stage 4: Conglomerate Diversification. The final stage occurs when the differentiation of products and services is rather complete: our company makes icebreakers that have nothing to do with canoes (except in some managerial mind that both are boats). Hence the divisions can be run as full-fledged businesses in their own right. Hydro Quebec, for instance, established a consulting division to offer its world-class engineering capabilities to power companies abroad.

So far, this discussion has concentrated on the diversification of products and services. But companies can also diversify their customers as well as their regions of operation—for example, selling the canoes to summer camps or to hotels in the English Lake District. This amounts to a more limited form of diversification because, with identical products for all customers or regions, the headquarters is inclined to keep central control of certain critical functions—say, the design of the canoes, if not the selling of them—thus maintaining some aspects of the integrated structure. Just have a look at the stores of a global retail chain.

The Basic Divisional Structure

True divisions function with considerable autonomy, from each other as well as from the central headquarters, subject mainly to the performance controls of analysts at that headquarters. They set the targets and monitor the results. These controls are not supposed to be intrusive—the division managers are supposed to run their own businesses—but they can become so when the measures keep ratcheting up.

Some important roles do, however, always remain at the headquarters: (1) managing the portfolio of divisions (namely which ones to add, keep, close, or sell); (2) appointing and, when necessary, replacing the division managers; (3) moving the funds around the divisions, to favor those perceived to have the greatest potential for growth while drawing funds out of those that don’t (sometimes called “cash cows”); and (4) providing certain support services for all the divisions, such as legal counsel and government relations. As O’Toole and Bennis have written about the federal structure, “The central authority establishes the why and the what; the units are responsible for the how.”101 Does

all this constitute decentralization (see box)?

The Divisions Driven to the Programmed Machine

In principle, the divisions themselves can take on any structural form. In practice, one form tends to be favored over the others.

Imagine if McDonald’s acquired Amazon. Don’t hold your breath, but if it did, no matter how different their businesses, with both companies being rather machine-like, that combination could conceivably work. Now imagine, instead, if McDonald’s acquired Apple. This would not be a happy union, especially for all those Apple engineers whose idea of innovation is not an Egg McMuffin. A Project Pioneer cannot function effectively under the control of a Programmed Machine, with headquarters’ analysts descending on these engineers in search of efficiency at the expense of creativity. They needs slack, not a straightjacket.

One conclusion in Chapter 6 was that the greater the external control of an organization, the more centralized and formalized its structure, these being the prime characteristics of the machine organization (as was elaborated in Chapter 8). The standards tend to formalize the structure of the divisions, and holding their chiefs responsible for meeting these standards tends to centralize them. Therefore the Divisional Form is inclined to drive its divisions toward the machine form, even when they require a different one. For example, the ups and downs associated with project work can be anathema to a headquarters that expects steady increases in performance.

Shortly after Jack Welch became CEO of General Electric, one of his advisers, who had read an early version of this book, called me with a question: What to do with the GE divisions that were more like adhocracies—say, the maker of jet engines compared with light bulbs. Keep the headquarters technocrats at bay, I suggested, by designating these divisions as Welch’s own preserves. In effect, use a personal structure at HQ to protect those divisions.

This was illustrated poignantly in another experience I had, with a British company called Thorn EMI, a conglomerate that combined Jules Thorn’s original lighting business with the EMI Music company and another business. An executive there told me that “since Thorn died, nobody knows how to run this place.” Thorn would seem to have run it, not as a classic Divisional Form, but as his Personal Enterprise. Could it be that the only way to run a conglomerate successfully, for a time at least, is to have an astute CEO who picks the right businesses and the right people to manage them?

The Cons of Conglomeration

The conglomerates of business do not have a happy record, at least in the United States. These have come and gone in waves, frequently put together by successful entrepreneurs who diversified companies that eventually collapsed.

Why, then, do conglomerates keep coming back into fashion, time after time? Perhaps because too many successful companies run out of high-growth opportunities in their own business, but not out of executives who believe they can manage any business, driven by stock market analysts clamoring for steadily greater growth. After all, there have been no shortage of investors willing to go with superstar successes, such as a Google, or a Beatrice Foods that ended up with four hundred businesses, many in its earlier dairy industry but others in car rentals, luggage, and more, before all that collapsed. If Beatrice had been so good at milking one business, why not four hundred of them, and the me-too investors in the bargain?

There have been exceptions, such as a GE that pulled off conglomeration for quite a while before it consolidated. And conglomerates have sometimes fared better in other parts of the world, especially Asia. For example, Tata of India has been successful with an extraordinary array of businesses. Could this be because control of its voting shares has remained with a set of family trusts that keep the stock market analysts at bay? Or that its most successful CEO was skilled at picking heads of the different businesses, to whom he gave substantial independence, while socializing them carefully into the Tata culture?102

The conglomerate has usually been compared to the single, functionally structured business. But from the point of view of economic development, perhaps it should be compared with a set of independent businesses, each with its own board of directors and owners. Here are some of the pros and cons.

1. The efficient allocation of capital. On the one hand, it has been claimed that a headquarters can know its businesses better and move money between them faster. On the other hand, it has been claimed that investors can diversify their portfolios cheaper and quicker (bearing in mind that conglomerates can pay a premium for the businesses they acquire).

2. The training of general managers. By running their own businesses, the division heads can develop their managerial skills. But if autonomy is so good for developing managers, might not more autonomy be better? The division managers have a headquarters to lean on, and be leaned on by, whereas independent CEOs might learn better from their own mistakes. One prominent self-proclaimed “deconglomerater” ended up “selling divisions back to their managers. The reason is obvious. The managers know what they are doing.”103

3. The spreading of risk. Operating in different businesses spreads the risk, compared with having all the eggs in one business. But the risk can spread the other way too—for example, when a nuclear power division signs a disastrous contract for uranium that bankrupts the entire conglomerate. Moreover, conglomeration can conceal a de facto bankruptcy when the HQ believes it can turn a failing business around, whereas market forces may be able to rid the economy of independent failing businesses more quickly.

4. The enhancement of strategic responsiveness. Each division can fine tune its individual business while the headquarters can focus on the overall portfolio of businesses. But with relentless pressure from a headquarters for steadily higher performance, the division managers might be discouraged from taking risks that do not pay off quickly, whereas an independent business might be able to find patient capital that allows it to take those risks. “[M]ajor new developments are, with few exceptions, made outside the major firms in the industry. Those exceptions tend to be single-product companies whose top managements are committed to true product leadership. . . . Instead, the diversified companies give us a steady diet of small incremental change.”104

To conclude, the advantages of conglomeration might disappear with rectification of the problems it is claimed to address, such as inefficient capital markets and weak boards of independent companies. Trying to manage a company that does not know what business it is in can amount to diversifiction.105 Hence, from a social no less than an economic point of view, societies may be better off correcting fundamental inefficiencies in their economic systems than supporting private administrative arrangements to overcome them (see box).

The Divisional Form beyond Business

When business adopts some new structure or technique, expect much of government to follow suit. And so it has been with the Divisional Form, including its predisposition to control through measures of performance.

This is encouraged by the fact that government is the ultimate conglomerate. Transportation, health care, education, tax collection, and much more all report up one hierarchy, culminating in the government in power. Even many government departments are conglomerates in their own right. Consider the Department of Transportation—most every country has one. It sounds fine, but tell me: What do the regulation of trucks on the road, control of airplanes in the air, and patrol of boats at sea have in common, besides the notion in our heads that all are about vehicles that move?

Why do governments create these unnatural units? Perhaps because they have to limit the size of their cabinets. If Transportation was split into three separate departments, each requiring its own minister, and other departments followed suit, cabinets would become unmanageable. Better, apparently, to render the departments of government unmanageable.

What’s the head of a Department of Transportation to do when other people manage each of its real parts? When considering an answer, bear in mind that there can be nothing more dangerous in an organization than a manager with nothing to do. That is because most managers are energetic: they will find something to do, like adding new measures of performance, or calling meetings of the heads of disassociated units to exploit synergies where there are none to be found.

The popular fix for the problems of managing government, called the New Public Management (meaning the old corporate practices), pours oil on this fire. Let the managers manage the departments, it proclaims, be “accountable” in the popular word, subject to meeting the performance targets imposed by analysts in the central technostructure. In other words, use the Divisional Form.

But this is no fix at all, for three reasons. First, as noted, the goals of government are significantly social and therefore often not amenable to workable measurement. Quality thus suffers. Second, because the politicians are the ones ultimately accountable, to the public, they often preempt the accountability of the public sector managers. Come some crisis, they can be all over them. And third, while the markets can bring down dysfunctional companies, there is no mechanism to bring down dysfunctional government departments. Hence many just fester.

Consider what excessive performance measuring has done to so much public education—for example, by the use of multiple-choice examinations that violate the imagination of children. Very efficient indeed. As for health care, when a senior civil servant in the UK was asked why his health department measured so much, he replied: “What else can we do when we don’t know what’s going on?” How about leaving your office, to find out what’s going on—for instance, that your measures may be driving the professionals quite literally to distraction?

Much the same can be concluded about the use of the Divisional Form in the plural sector. Many of the associations in the sector— charities, NGOs, foundations, and so on—serve social needs. This renders their use of the conventional Divisional Form problematic, at least in the conglomerate version where it relies on numerical controls. Limited forms of diversification—for example, based on geographic region—can work better, as in the Red Cross Federation with its national societies.

Some business schools in the US have opened campuses in other countries and some hospitals have created clones in other cities to leverage their reputation. But is continuing to function under one institutional umbrella preferable to cutting the new places loose once they have become established?

One thing is clear: Governments and associations should no more be run like businesses than should businesses be run like governments and associations.

To conclude, in its ultimate, conglomerate version, the Divisional Form can be described as a structure on the edge of a cliff. Taking one step ahead, it shatters into pieces on the rocks below. Behind are the safer places of an intermediate form (related-product, byproduct, geographic), with some synergy but less measurement.