5

The Calculus of Burnout and Leadership

Every system is perfectly designed to produce precisely the results it gets.

PAUL BATALDEN (ADAPTING ARTHUR JONES’S INSIGHT)1

In the Introduction, I discussed the concept of “burning in versus burning out” and the importance of reigniting our passion while protecting it. “Burning in” means using our passion to fuel the flames of our “deep joy” in caring for patients, using the heat of the friction between job stressors and resilience to power us. Reigniting your passion requires the application of the disciplines of personal resilience and the art of strategic optimism to protect that passion. Chapters 2 and 3 provided a taxonomy of burnout, with definitions driving solutions. These definitions create shared mental models, which form the basis of a deeply and widely understood foundation from which the entire team can work on burnout. Armed with these practical definitions and shared mental models, let us move to how to put those definitions to work in ways that make our patients’ lives better, our jobs easier, and our teams less likely to burn out. That is the foundation for the following concepts:

Lead yourself, lead your team.

Protect yourself, protect your team.

The work begins within.

The Calculus of Burnout Results in a Passion Disconnect

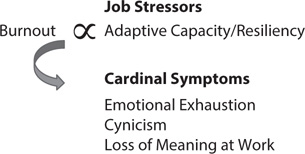

The calculus for decreasing burnout is very simple: decrease the “numerator” of job stressors while increasing the “denominator” of adaptive capacity or resiliency (Figure 5-1). Throughout the book, this “numerator”/“denominator” terminology is used to identify burnout problems, as well as the solutions necessary to deal with them. (Remember that resiliency and adaptive capacity are synonymous in the burnout definition and are used interchangeably throughout the book.)

Figure 5-1: Definitions Drive Solutions

Burnout results in a passion disconnect, and passion is the fuel that drives us in the difficult job of caring for patients. Without passion, we are truly “running on empty,” in the words of singer-songwriter Jackson Browne. Decreasing job stressors while increasing resiliency is the path toward a passion reconnect, which “fills our tanks.”

The framework for understanding burnout comprises three elements:

1. Instilling a culture of passion and professional fulfillment

2. Hardwiring flow and fulfillment into systems and processes

3. Reigniting passion and personal resilience

The cultures of our organizations and the systems and processes by which healthcare is provided are characterized by organizational resilience, while reigniting passion demonstrates personal resilience. I will discuss the roles each plays in battling burnout in detail. Ninety percent of the literature on burnout is focused on diagnosis, with a scant (but increasing) 10 percent focused on prevention and solutions.2 Further, most of the work on burnout has concentrated almost exclusively on personal resilience, while far less focuses on the necessity of changing the culture and systems in which we work. When the system produces burnout in 50 percent of its talent, the system must be changed, not just the people. Paradoxically, the pathway to improving culture and systems arises from the personal transformations of individual team members, which is why I say “the work begins within.” As those transformations occur, individuals, then teams, then organizations, then systems accelerate the pace of innovation.

One central message of this book is that, with effective, positive, and proactive leadership (at both the organizational and personal levels), the pathway to a passion reconnect is not only possible but predictable. Conversely, a lack of leadership is precisely how the scourge of burnout reached epidemic proportions. Battling healthcare burnout is one of the most important aspects of healthcare leadership, as well as a significant challenge.

My experience and that of many others, including national leaders like Tom Jenike at Novant (Chapter 12), John Brennan at Wellstar (Chapter 16), Steve Motew at Inova (Chapter 15), and Nicholas Beamon at OneTeam Leadership (Chapters 12, 15, and 16), is that, as leaders, we should begin the work ourselves and extend it to the organization, not the opposite.

Changing Results Requires Changing the System: “Data, Delta, Decision”

Putting definitions to work requires a deep understanding of the role of systems in healthcare. It starts with a simple question: “Do you love the results of your hospital or healthcare system?” If the answer is yes, then you have a perfect system, designed to deliver precisely those results. If the answer is no or “It depends,” then there is an inexorable corollary—if you don’t love your results or you love some but hate others, you must change the system to get different results. You cannot hate your results and love the system—the system is designed to get precisely those results. As we will explore in more detail, change is often hard, so we must have a system to foster positive change. The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard noted, “The most important questions in life are simultaneously those asked least often.”3 The important question of how to effectively and nimbly change the system may be asked least often—but it is at the heart of battling burnout. The three constant questions focus on the core of change (Figure 5-2):

What are the data?

What is the delta?

What is the decision?

“What are the data?” refers to the metrics of the measures by which we judge success. “What is the delta?” refers to the difference between our target metrics and the metrics obtained during the measurement period. “What is the decision?” is specifically how the system will be changed to obtain the target metrics, since the system as it operated within the measurement period was perfectly designed to get precisely the results it got. Far too many leaders choose to “exhort the troops” to get higher metrics, instead of understanding that they are working in a flawed system that must be changed.

Figure 5-2: The Three Core Elements

What does this have to do with burnout? First, the pressure to hit targeted metrics is in itself a stressor to those charged with reaching them, so the burnout “numerator” is higher. How can we change the system to increase the “denominator” of adaptive capacity in a commensurate fashion, so we don’t produce burnout? The more that systems and processes are hardwired in an evidence-based fashion, the better it works for the patients and the people who take care of them. The three constant questions develop solutions that cut across all three core elements (changing the culture, hardwiring flow and fulfillment, and developing personal resiliency).

The Elements Necessary to Develop an Effective Change Strategy

How can we change the system itself to avoid burning out our teams? There are three important concepts:

• healthcare as a complex, adaptive system

• “connecting the gears”

• a pragmatic theory of intrinsic motivation, or “getting the ‘why’ right before the ‘how’”

HEALTHCARE AS A COMPLEX, ADAPTIVE SYSTEM

The great leadership guru Peter Drucker4 correctly noted that healthcare is a complex adaptive system, with multiple highly interrelated processes performed by professionals (physicians, nurses, and healthcare leaders) and essential services staff (laboratory, imaging, environmental services, food services, etc.). Sadly, Drucker’s insight came only two years before his death, so we are deprived of an in-depth exegesis of healthcare from his highly analytical mind. Far too often it is subject to what Phillip Ensor originally described as functional silos,5 in which interrelated processes are not sufficiently linked in a seamless fashion.

An example that demonstrates that healthcare is a complex, adaptive system comes from the work of Peter Senge, who was among the first to effectively articulate the critical nature of systems thinking.6 Senge asked one of his colleagues, Daniel Kim, to devise a game that would demonstrate the concepts of systems thinking as a practical example of the way in which even seemingly disparate processes influence not just other processes but all other processes. The result was a game, which is still in use today, called Friday Night at the ER. Kim and his associates recognized that the complex, adaptive systems present in emergency departments were a way of teaching systems thinking to people while demonstrating the importance of moving from “silo thinking to systems thinking.”7 In healthcare, individual teams or units often attempt to maximize their results without sufficient thought of the impact on the overall system—or even the overall health of the patient. Leadership to improve burnout must emphasize the role systems thinking plays.

CONNECTING THE GEARS

Successful healthcare leadership requires disciplined strategies and tactics in the areas of most importance, which are, at a minimum, the following:

• clinical excellence

• patient experience

• patient safety—high-reliability organizations

• hardwiring flow for efficient, effective processes and systems

I call it “connecting the gears” (Figure 5-3).8 There are three important insights to this concept, the first of which is obvious and intuitive, while the second and third are less so. First, whenever we change any of the gears, it affects the patient. If moving one of those gears results in a negative impact for the patient, don’t do it—or at a minimum rethink the change and how the negative impact could be removed.

The second insight is that each of those gears comprises a detailed, disciplined, and evidence-based set of systems and processes, not just “words on the walls.” The challenge of leadership is not just to identify what success looks like and how it will be measured, but to enact an evidence-based path by which to get there.

Third, and this is the subtlest of the insights, is that you cannot move any of the gears without moving all the gears, since healthcare is a complex, adaptive system. For example, it is not uncommon in healthcare for teams to improve the results in their unit, while harming the results in others.

If we do not “connect the gears” in ways that are meaningful and actionable, both for the patient and for those who care for the patient, we inevitably create rework, inefficient and ineffective processes, poor results, frustration, friction, and burnout. But if each of those gears has a discrete set of disciplined, evidence-based solutions delineated, not only is burnout prevented, but passion can be reconnected.

Figure 5-3: Connecting the Gears

CASE STUDY

An ICU team has been focused on reducing length of stay (LOS) as a key performance indicator. Working as a team, the ICU nurses and physicians have reduced LOS by 1.2 days, a metric that was celebrated at the hospital’s management team meeting. However, shortly after, it was noted that there was a high rate of “bounce-back,” in which patients are transferred out of the ICU who must be transferred back as a result of clinical deterioration, which was a source of dissatisfaction for all team members, the patients, and their families, as well as a risk to patient safety. It also resulted in an increase in total hospital LOS. The root cause in this situation was a failure to consider the systemic nature of patient care and the downstream effect that improving one metric may have on others.

GETTING THE “WHY” RIGHT BEFORE THE “HOW”: AN INTRINSIC THEORY OF MOTIVATION

Highly trained and motivated members of the healthcare team always want to know, “How do we provide superior outcomes and a great experience for all of our patients?” That question, while understandable, misses Nietzsche’s point that it is essential to discover the “why” that motivates professionals before the details of the evidence-based “hows” can effectively be put into action. Healthcare leaders should always start with the “why,” as reflected in these common questions from the staff:

• Why are we doing this?

• Why are we changing?

• Why can’t we keep doing what we’re doing?

• Why is this change better than the way we’re doing it?

The simplest answer, as noted throughout the book, is the following:

The way we’re working isn’t working.

Few healthcare professionals or leaders would claim that their systems are optimally designed, staffed, funded, resourced, supported, and maintained. The processes by which care is provided are often flawed and need improvement, as virtually all hospitals and healthcare systems operate in a significantly capacity-constrained environment. Evidence-based approaches make the job better by making the work easier. Successful implementation requires a disciplined approach applied to every patient every time by every team member. “Lead yourself, lead your team” is the key to that.

The “Why” Is That It Will Make the Job Easier In change efforts, failure occurs when team members believe the only reason to embrace excellence is that it is good for improving scores and building market share. (Try telling nurses on a busy unit that the reward for great patient experience is more patients. That won’t seem like a reward to many of them.) Before asking others to master the “how-to,” it is necessary for them to comprehend the “why-to.”9

Why Get It Right? A-Team versus B-Team Members This question can be answered by asking the team to finish this sentence:

The number one reason to get things right in healthcare is …

Team members will state that it is good for the patient, the family, patient safety, risk reduction, market share, and metrics scores. These are all correct, but leaders must emphasize that the best “why” is this:

It makes your job easier.10

Like most people, healthcare professionals do not change easily. The most compelling, effective, and sustainable reason to change—for example, by improving patient experience, hardwiring flow, seeking clinical excellence, improving patient safety, or developing burnout solutions—is that it makes the job easier for the team. Providing quality clinical care at the bedside is a difficult job that seems to get more challenging every day. It should not be a surprise that team members push back when leaders say, “Oh, and by the way, get your scores up, too.” For too many care providers, scorecards are just one more mandate among an already overwhelming list of “musts.”

To demonstrate this concept, simply ask members of the team the question,

Do you offer quality, patient-centered care?

Some will say yes and some will say no, but the vast majority will say, “Sometimes” or “It depends.” When the answer is “It depends,” what does it depend on? The good news is that the team knows, as the following exercise shows. To determine the specific cause of this variability, consider asking the staff the following:

Are there days when you come to work, see the people you are working with, and say to yourself, “Bring it on! Whatever we’ve got to do today, these folks can make it happen”?

The answer will be yes. When asked to describe what they call the members of that team, they will answer, “the A-team.” When asked, the team members will quickly list the attributes of the A-team:10

• positive

• proactive

• confident

• compassionate

• competent

• good communicators

• team players

• trustworthy

• do whatever it takes

• have a sense of humor

Now ask the team,

Are there also days when you go to work, see who you’re working with, and think, “Shoot me, shoot me, shoot me. I can’t work with them—I worked with them yesterday. Who in the world makes the schedule around here, anyway?”

That team is known as the B-team, and the staff will describe the characteristics of its members as follows:

• negative

• overreactive and hypersensitive

• confused about the team goals

• negative, backstabbing communicators

• lazy, shifting responsibility

• frequently arrive late to work

• always have an excuse about why they didn’t …

• constant complainers with a victim mentality

Everyone on the team can name the B-team members—except of course the B-team members themselves. Amusing nicknames could be applied to members of this group.

• Nurse Ratched, the dour nurse from Ken Kesey’s book One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, whom everyone recognizes (except, of course, Nurse Ratched herself)

• Tomas Torquemada, the grand inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition … and it can feel as if one Dr. “Torquemada” can extract more pain in a single 10-hour day than Tomas Torquemada did in 10 years as the grand inquisitor

• Administrator Scrooge, the coldhearted, miserly “C-suite” member who immediately says “No!” to all ideas that don’t have a guaranteed significant return on investment, strangling innovation and furthering burnout

Finally, ask the team members,

How many B-team members does it take to destroy an entire shift?

They will respond emphatically, in unison, “One!” One person can destroy, or at least dramatically lower, the morale of an entire, busy clinical unit. It happens every day. These insights point to ways to use the performance gap to drive intrinsic instead of extrinsic change.

The “Why” in Practice Once the dichotomy of the A-team and B-team has been explained and demonstrated, there is an opportunity to make two important points. The “why” of change is that it makes the team members’ jobs easier. If not, the change is not important. This point can be illustrated through the A-team/B-team exercise just described (and discussed in more detail in Chapter 17). The A-team attributes are evidence-based pathways to success; B-team attributes make the job harder for the rest of the team. All team members want to work with A-team members, all the time. If you can give them that hope, you will succeed.

The “why” of change also gives everyone hope that—finally—the B-team members will be held accountable for their actions, which affect our patients and their families and destroy our morale. Without this intervention, staff members are left to wonder when, if ever, we as healthcare leaders will enforce that accountability.

The role of the leader is to identify, accentuate, train for, and reward A-team behaviors while simultaneously searching for, confronting, and eliminating B-team behaviors, which should not be tolerated. This is at the heart of why effective leaders have lower burnout rates among their teams.

Leaders who accept the responsibility of ensuring patient focus and team collaboration and accountability tap into the brilliant wisdom of people like psychologists Abraham Maslow11 and Eric Erikson12 and psychiatrist Victor Frankl.13 Each, in their own way, recognized this sage wisdom: “All meaningful and lasting change is intrinsically, not extrinsically, motivated.”

Helping healthcare team members understand that the leadership team is fanatically dedicated to making their jobs easier not only communicates the “why” of change but also demonstrates that the leaders and their teams will be ready to bear almost any “how.” The result of combined leader and staff buy-in is that metrics will rise and stay elevated because the “servant hearts” of the team will become intrinsically motivated to make their own jobs easier and make others’ jobs easier as well. But far more important is the signal of hope it sends to team members that their jobs will be easier.

Then, and only then, is it appropriate to move on to the question of “how,” as Peter Block indicates in the title of his provocative book The Answer to How Is Yes: Acting on What Matters.14 Leaders are more successful when they focus less on the scores and more on the “why,” asking,

What have I done today that makes life easier for my team and my patients?

In doing so, a powerful and sustainable force in your organization will be unleashed: intrinsic motivation for staff to always be members of the A-team.

Summary

• Since every system is perfectly designed to produce precisely the results it gets if healthcare leaders want to change the results, they must be courageous enough to change the system, since the way we’re working isn’t working.

• The three elements of a systems approach to burnout are the following:

1. Instilling a culture of passion and professional fulfillment

2. Hardwiring flow and fulfillment into systems and processes

3. Reigniting passion and personal resilience

• Three questions should drive our conversations to change the system: “What are the data?”; “What is the delta?”; and “What is the decision?”

• Effective concepts to consider when developing change strategies are the following:

◦ healthcare as a complex, adaptive system

◦ “connecting the gears”

◦ intrinsic motivation—getting the “why” right before the “how”

• The A-team versus B-team exercise demonstrates that “the number one reason to get this right is that it makes the job easier!”