17

Tools for Personal Passion and Adaptive Capacity

There are 10 tools designed to help rediscover and reignite personal passion and build personal adaptive capacity or resilience.

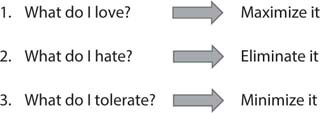

Tool 1: Love, Hate, Tolerate

The “love, hate, tolerate” tool is the one that resonates the most with team members. Along with the “deep joy, deep need” tool, it targets the “why” of making the job easier, since everyone wants to spend as much of the day as possible doing what they love. Use Figure 17-1 as the basis for the team’s discussion.

• “Love” is why you came and why you stay, what wakes you up in the morning, what fires you up, your “deep joy” (see the next tool). Once this is listed, ask what can be done to maximize it.

• “Hate” is the job stressors burning you out, what keeps you up at night, what holds you down. What can be done to eliminate what we hate?

• “Tolerate” is the in-between, the things that neither drag you down nor lift you up, the necessities of the work. What can we do to minimize these more readily?

Once these areas are known, develop and implement strategies that correlate with them and make sure they are translated to specific actions reflected on the Mutual Accountability Jumbotron (Chapter 6). Recall the work done by Tait Shanafelt and colleagues that indicated, at least in an academic physician practice, that physicians who were able to spend about 20 percent of their time on their “love” or “deep joy” area were much better able to tolerate the things that otherwise burned them out.1 Tap into this to help ensure that physicians, nurses, and other team members are able to pursue, to the best extent possible, what they love.

Figure 17-1: The “Love, Hate, Tolerate” Tool

Revisit the “love, hate, tolerate” tool as often as necessary, but no less than quarterly.

Tool 2: Deep Joy, Deep Need

This is an important tool to use for all teams in the first phase of battling burnout since it is at the heart of the “why” that brought each of us to healthcare. It was referred to in the Introduction and Chapter 8. Start with “why” by accentuating the importance of making the job easier and patients’ lives better.

Ask the team, “What is the deep joy that made you choose your career?”2 “How did your deep joy sustain you through the hard work of school, training, testing, and continuing education?” When job stressors grow and your adaptive capacity is thinning, reach back and rediscover your deep joy.

WRITE A LETTER

Take a piece of paper (or open your computer) and write a deeply passionate note—to yourself. Subject? “I became a doctor/nurse/advanced practice provider/ healthcare leader because …” If that doesn’t help you reignite your passion and develop personal resilience, I’d be surprised.

FIND A PICTURE

Now find a picture from when you were in school or in residency. Take 15 minutes from your day and stare at that photograph—intently—and introduce yourself. Tell him or her who you have become. Don’t focus on salary, positions, or accolades—focus on your deep joy and whether you have stayed true to it. Ask that person to help you find your way back to that joy.

Tool 3: Sing with All Your Voices—Use “Love” to Define Meaningful Work and Reinvent Yourself

This tool is closely related to the “love, hate, tolerate” tool and the “deep joy, deep need” tool and can be used in conjunction with them. Performing self-identified meaningful work as 20 percent or more of the total work done decreases burnout by 50 percent, at least in an academic setting. As the great Chuck Stokes notes, with artificial intelligence doubling knowledge every 18 months, those entering (or staying) in healthcare will need to reinvent themselves, since the work will be changing to keep pace with the knowledge.3 Ask team members to use the “love” part of the “love, hate, tolerate” tool to help them identify what they consider to be the most meaningful work they do.

Ask them to consider what percentage of their time they spend on this meaningful work each day or week and write the percentage down. Ask how they increase that percentage. Ask whether that percentage has changed over the last year.

Use the “hate” and “tolerate” lists to identify the areas in which they may envision reinventing themselves. If you were not doing this job, what other job within healthcare would help you reinvent yourself to increase meaningful work (“loves”)?

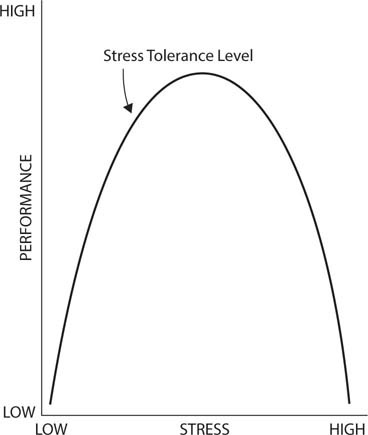

Tool 4: Stress Tolerance Level

While increasing stress causes us to increase performance, all of us have a point at which increasing stress causes our performance to peak—and then rapidly decline. That is known as the “Stress Tolerance Level.” This exercise helps the team members recognize it.

1. Frame the issue by reminding team members that burnout is a ratio of job stressors to adaptive capacity or resiliency. As job stressors rise, we have to adapt.

2. Use Figure 17-2 as an educational tool to show that stress can be positive, motivational stress, which is on the left side of the curve, where, as stress rises, performance also rises. But it can also be negative stress or distress, where increased stress causes a dramatic fall-off in performance.

Figure 17-2: Stress Tolerance Level

3. Make the point that we all have a stress tolerance level (STL), past which performance will plummet.

4. Ask these questions:

– What do you look like as you approach your STL?

– Do you recognize that in yourself?

– If you don’t, your fellow team members (and your family) can tell you precisely how you look and act when approaching your STL, if you have the courage to ask and they have the courage to tell you.

– Can you think of a time you were approaching your STL?

– Did you “tip over”? Why?

– If not, how did you “slide back down” the curve?

Tool 5: Strategic Optimism/Creative Energy

Because energy and passion fuel our ability to lead, maximizing creative energy is a powerful “why” to reignite passion and increase personal resiliency. One factor determining workload demands and the capacity to deal with them is the amount of energy required to meet the demands (stressors) versus the energy available to you while at work (adaptive energy capacity). Similarly, the concept of strategic optimism is closely aligned with creative energy, and they can be used together or separately. The tool is designed to help team members understand the importance of leveraging their optimism strategically and closing their energy packets as a renewable source of energy.

1. Introduce the concept that energy drives all our efforts, mentally, physically, intellectually, and psychologically, and is paired with passion.

2. Define strategic optimism as the principle that life’s greatest asset is our capacity for optimism, which is the ability to assess a situation and invest it with the most positive practical possibility. Since it is an asset, we are duty bound to maximize the return on investment to ensure we use it wisely and well and increase its “wealth,” since none of us has unlimited optimism.

3. Joan Kyes used the term creative energy to describe how to best use energy creatively and strategically. While some people seem to have inexhaustible energy, Kyes believed that everyone has basically the same “energy reservoir” from which to draw. But people use that reservoir differently.

4. Each time an activity or project is started, a person removes an “energy packet” or optimism packet matched to the needs of the challenge, which depletes the reservoir but gives enough energy (presumably) for the task.

5. The more tasks you have “open” at one time, the less energy in the “tank” of your energy reservoir.

6. People with high energy levels don’t actually have more energy; they simply use it more efficiently by completing the task and “redepositing” that energy back into the tank.

7. People who are constantly exhausted (a core symptom of burnout) probably have too many energy packets open at once, and thus have insufficient energy to do anything else.

8. Kyes’s advice is to “close your energy packets quickly and efficiently—don’t let them continue to drain you.”

9. Once these concepts are developed, ask a series of questions:

– What do you think is the fuel level of your energy tank or reservoir?

– How many energy packets do you have open?

– Why are they still open? Did you open the wrong package for the project?

– Or are you “letting the perfect be the enemy of the good”?

– What can you do today to close one to three of those packets? Write it down. Now do it.

– Report back (to yourself) tomorrow—did you close those packets?

– For the ones you can’t close, make a plan to close them tomorrow, this week, this month … or let the project go.

– Do you feel better now that the energy packets are back in the tank?

– How much strategic optimism do you have right now?

– Since it is not an infinite resource, how will you choose to invest your optimism to maximize your return on investment?

– Since our last meeting, what have you invested your optimism and energy in and how has it gone?

Tool 6: Disconnect Your Hot Buttons

We can be massively distracted from the “why” of making our jobs easier when we allow our “hot buttons” to deflect energy, attention, and passion from our work. Hot buttons are ubiquitous, so we all need work on this “why” distraction.4

1. Introduce the concept of hot buttons, which are verbal or nonverbal situations in which our attention and energy are diverted from the task or work, causing us to involuntarily react in a negative way.

2. If possible, give an example of one of your hot buttons. Here is one of mine: When I am examining a patient and I ask them whether I can listen to their lungs, I put my stethoscope in my ears, place the chest piece on their chest, and … they start talking. I don’t know why, but this is one of my hot buttons—it drives me to distraction.

3. Ask team members to go through the following process:

– What are your hot buttons? Write them down.

– How do you react? How do you think, feel, and act?

– Recognize that they are not the patients’ or team members’ hot buttons—they are yours; you own them and only you can disconnect them.

– Disconnect them by clearly identifying them, writing them down, and reflecting on why and where they arose.

– Now use positive mental imaging to picture them happening and what you would do, say, and think to make them positive—or at least prevent yourself from reacting to them.

– Use scripts for disconnecting them.

– Continue to reinforce this over time.

Tool 7: Leave a Legacy

Making a difference in someone’s life is what we all sought when we first answered our “deep joy” by choosing a healthcare career. Reconnect passion to purpose by making that difference more transparent. Nothing achieves the goals of “Lead yourself, lead your team” and “Invest in yourself, invest in your team” more powerfully than the legacy we leave.

1. Frame the discussion by briefly summarizing the “deep joy, deep need” concept and tying it to reigniting passion and personal resiliency.

2. Move to developing an understanding that one of the most fundamental human longings is to make a difference in others’ lives. Given how hard it is to do the work of healthcare, we all deserve to reward ourselves while rewarding others.

3. “Leaving a legacy” means being able to connect the work to the passion by understanding our impact on others.

4. Our legacy is not the amount of money or property or life insurance we leave to our family. It is something much more profound and meaningful. The medieval Latin root of legacy means “an ambassador or envoy sent on a special, often sacred mission.” We are all ambassadors on a mission for the benefit of our patients.

5. In healthcare we are fortunate since our legacy is measured by a simple yet stark metric: our legacy is the difference we make for each patient for whom we care each day—one patient at a time.

6. Ask the team to adopt a new habit—every time they leave to go home after work, ask them to pause a moment and reflect:

– “What did I leave in there?”

– “What legacy did I leave behind today?”

– If you are not pleased with what you left behind today, what will you leave behind tomorrow?

– What, specifically, will you do to make tomorrow’s legacy better than today’s?

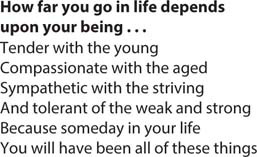

An additional tool for “leave a legacy” is one I learned from my mentor, Chuck Stokes, who often quoted the question posed by George Washington Carver in Figure 17-3. Ask the team how they would complete that sentence. Then show them Figure 17-4, which finishes Carver’s message.5

Close with this thought:

Every day, those of us on the healthcare team have the great honor and privilege of continuously being

• tender with the young

• compassionate with the aged

• sympathetic to the striving, and

• tolerant of the weak and strong, because

• every day you will serve all these people.

Figure 17-3: The Beginning of George Washington Carver’s Important Message

Figure 17-4: George Washington Carver’s Full Message

To be called to the great and noble work of healthcare, in which we not only can leave a legacy every day we work but can also measure that legacy, one patient at a time:

• what a challenge

• what a responsibility

• what an opportunity

• and ultimately what a joy

What better legacy can we in healthcare leave?

Tool 8: Do the Best You Can—Leave Your Guilt in the Trunk

This tool helps emphasize that we must forgive ourselves before forgiving others, in service of “leaving your guilt in the trunk.” It makes the job easier because it helps us focus on doing the best we can and leaving behind idealized versions of ourselves as perfect nurses, doctors, and team members.

1. Simply write the phrase “Do the best you can” on a whiteboard or flip chart.

2. Then say, “I’m going to ask several of you to just read what I’ve written. Listen carefully to what you hear.”

3. Ask someone to read the phrase out loud.

4. Listen to their response and then ask another and another.

5. After four to five people have read it, ask the audience what they heard.

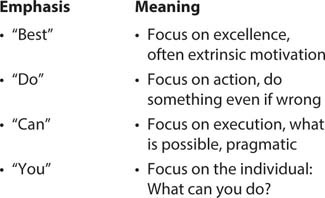

6. Some will have emphasized “do,” others “best,” others “can.” (Rarely does anyone emphasize “you.”)

7. Discuss what they think the different emphasis means. (You can use Figure 17-5 if you like.)

8. Ask, “What would it mean if we were a team that always celebrated our individual talents by saying, “Do the best you can”?

Tool 9: Keep a Gratitude Journal

One of the most powerful tools available is to keep a journal of your thoughts. The venerated Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius never wrote a book in his life. But he did keep a journal, known to us as his great work, Meditations.6 It is still read today by many. A gratitude journal allows us to remember patients, who are the lifeblood of healthcare. There is no better way to reconnect to passion than to remind ourselves of the great patients whose care was entrusted to us—a powerful “why.”

Figure 17-5: The “Do the Best You Can” Exercise

1. Frame the issue by making the point that the work we do is fundamentally heroic and in service to others.

2. Remind them of the three rules:2

– Rule 1: Always do the right thing for the patient.

– Rule 2: Always do the right thing for the people who take care of the patient.

– Rule 3: Never confuse rule 1 and rule 2.

3. At its core, our work is an honor in that it allows us to enter people’s lives to make them better in some small or large way.

4. There is a lot for which we should have gratitude in the course of the day—our patients, their families, and our teammates.

5. But we move so fast sometimes that it would be nice to have a way to capture those memories and thoughts.

6. A gratitude journal does just that—it is a discipline or habit of capturing positive moments so we can revisit and appreciate them later.

7. Make the point that journaling has a long and rich history of capturing the thoughts of great men and women. (Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations was never intended to be published; it is his journals to himself, reflecting on the wisdom—or lack thereof—of the day.)

8. There are many ways to keep such a journal.

– Keep three-by-five-inch cards in your lab coat or uniform so you can write down short notes about people for whom you are particularly grateful.

– I prefer to use small notebooks because I can use them at work, in the car before going home, or at home. This also makes it easy to keep them. I have at least 100 of these notebooks that I have filled over the years. It is a real pleasure to revisit them, remembering (and in some cases, bringing back to life) patients, families, and teammates who enriched my life and for whom I will forever be grateful.

9. The Duke WISER program uses Three Good Things, Acts of Kindness, Relationship Resilience, Awe-Inspiring Things, and other concepts that can be a great start to get you thinking. No format is perfect for everyone, but here are a few others that you may want to experiment with:

– Who and what made me laugh, smile, think, and perhaps cry today? (Remember Jim Valvano’s ESPY Awards speech from Chapter 8.)

– What went well today?

– Whom did I thank today?

– Whom should I have thanked today?

– How can I be more thoughtful tomorrow?

– I never want to forget …

10. I am often asked what to write in a note or say in a speech, and my answer is always the same: “Just open your heart and the words will come out.” Do the same with your journal.

Tool 10: Whom Do You Burn Out? Why?

“Why” is often about making our jobs easier, but it also can be making our teammates’ jobs easier. We are all leaders of ourselves and our teams. All great leaders have the integrity to ask, “What could I have done better?”

1. Once the team is familiar with the definitions of burnout and has worked to decrease job stressors and increase both organizational and personal adaptive capacity, return to the core concept, “The work begins within.”

2. Pose a series of blunt questions to the team to work on, including the toughest, which is the first question:

– Whom do you burn out?

– Why?

– How?

– What could you do differently to reduce burnout in those with whom you work?

– Are there trends by people, specialty, positions, and so on?

– At some level, are you proud of burning others out?

3. For those who are courageous enough to offer examples, give some constructive alternatives on how things could be handled differently:

– “What could I have done today to make your job easier?”

– “What do you want to see more of from me?”

– “What do you want to see less of from me?”

– “What B-team attributes did I exhibit today?”

– “How we can handle friction in the future so that we don’t burn each other out?”