10

Hardwiring Flow and Fulfillment

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence is not a virtue, but a habit.

ARISTOTLE, ETHICS1

If Aristotle is correct and we are what we repeatedly do, then what we do at work is guided by the systems and processes in which we do them. Much of the work on burnout has focused on personal resilience to the relative exclusion of changing the nature of the work and its consequences. Having a good or even a great attitude about doing work that burns us out should not be the primary solution—fixing work that produces a 50 percent burnout rate should be.

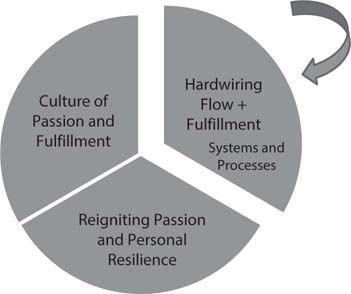

This requires changing the systems and processes by hardwiring flow and fulfillment into the work. Kirk Jensen and I coined the term hardwiring flow in 2009, defining it as follows: “Flow exists to the extent that value is added and waste is reduced to a product or service during a patient’s journey through the queues and service transitions of healthcare.”2 We titled our 2009 book Hardwiring Flow: Systems and Processes for Seamless Patient Care. We knew, based partially on Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s work,3 that flow as an optimal healthcare experience was attainable by concentrating on adding value and decreasing waste, which allows those working in the system to focus their talents to the maximum effect. But the subtitle is equally important, because it is the systems and processes that guide what we repeatedly do. Hardwiring flow means doing “smart stuff”—the stuff that adds value—while ceasing to do “stupid stuff” that creates waste, both of which allow us to use our talents more effectively and in a more fulfilling way. Flow and fulfillment are inextricable. We cannot attain or sustain fulfillment unless we hardwire our systems and processes for both flow and fulfillment. While it is common to measure flow exclusively by time, quality, and safety metrics, we must move to considering how our systems and processes affect fulfillment as well (Figure 10-1).

Figure 10-1: Hardwiring Flow and Fulfillment

Applying those disciplines consistently to allow patients to flow through the system is the province of leadership, which should identify the best practices to add value and decrease waste. But it cannot be done without the followership of those doing the work. This is true both because the people doing the work best understand the specific systems and processes and because they are the ones who most fully understand the details that produce burnout. Hardwiring flow and fulfillment into the systems and processes of the daily work is an important path to increasing organizational resilience.

Fulfillment in Healthcare

Curiously, a literature search for “fulfillment in healthcare” sends you to reams of articles on how fast one can get a product or service to a customer, not the deep personal sense of fulfillment needed to fuel our work. (Indeed, there is much more written in the “mindfulness” literature on fulfillment than in healthcare or scientific journals.)4–5 Yet this concept of “fully filling an order” may have some attractiveness as we define fulfillment in healthcare. In our case, what “order” are we fully filling? Fulfillment of what—and why? Our fulfillment is “filling the order” of our deeply held passions and our deep joy—what brought us to healthcare originally and is the fire that fuels our efforts. It allows us to use the flame to “burn in” instead of burning out. Fulfillment also entails an intense clarity about worthwhile goals and values that provide a connection to the patient.

The thousands of healthcare team members I spoke with about this issue consistently told me that these are the elements that give them fulfillment:

• connection with patients

• making meaningful differences for their patients

• clear, honorable goals

• clarity of the challenge as well as the impact of their work

• rapport with colleagues

• challenging cases that match abilities with the work needed

• the ability to focus on difficult tasks and accomplish them

• constant upgrade of skills to meet the constantly changing challenges

• doing difficult work aligned with their values

These and other responses fit well into the concept of flow as optimal experience that Csikszentmihalyi described. Later in this chapter I will discuss the concept of working “at the top of your license,” which is a clear example of professionals staying sufficiently challenged to experience flow at work. Critical care professionals such as emergency, ICU, trauma, and surgical physicians and nurses tell me without exception that their best days have been in the midst of crises and disasters, probably because of the challenge, clarity, and commitment needed to do the work. My experience and that of all of the people with whom I worked at the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, was that, as bad as that day was, it was the most satisfying day of our careers. In his great book Tribe,6 Sebastian Junger notes the same phenomenon among survivors of the Afghanistan war and Bosnian conflict. Those who worked on the front lines in caring for patients in the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 also describe feelings of flow and satisfaction when asked about that challenging time.7–8

Hardwiring Flow and Fulfillment Solutions

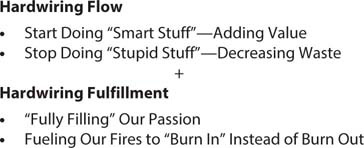

With our definition of hardwiring flow and fulfillment in mind, let’s proceed to how this concept can be used practically with specific strategies to increase organizational resiliency. These are listed by the six Maslach domains9 (Figure 10-2):

• diminishing workload demands and increasing adaptive capacity

• regaining or seizing control

• increasing rewards and recognition

• returning community to the team

• reestablishing fairness in an unfair world

• reinfusing values in the workplace

Figure 10-2: Solutions to Hardwire Flow and Fulfillment Matched to Maslach’s Six Domains of Burnout

Because of its dramatic, universal, and powerful effect on burnout—and because it cuts across all of the domains—taking on the electronic health record (EHR), the subject of Chapter 11, is perhaps the most powerful set of solutions to hardwire flow and fulfillment in healthcare. Finally, several of the solutions apply both to organizational resilience, because of their effects on systems and processes, and to personal resilience, so they are listed here and in the following chapter, where the emphasis is on how to use them personally to fuel our passion.

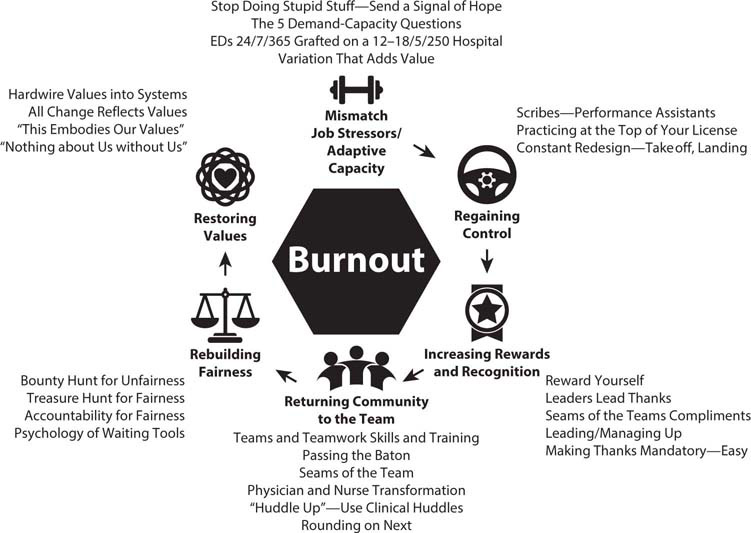

DIMINISHING WORKLOAD DEMANDS AND INCREASING ADAPTIVE CAPACITY

Designing and implementing solutions to improve systems and processes in order to diminish workload stressors while increasing the team’s adaptive capacity provide high leverage strategies to increase resilience and decrease burnout. Figure 10-3 shows these solutions.

Start Doing Smart Stuff, Stop Doing Stupid Stuff: Send a Signal of Hope

Hardwiring flow and fulfillment involves doing “smart stuff”—the evidence-based best practice systems and processes that produce superior flow metrics and allow the team to feel fulfilled. The concepts of lean healthcare and hardwiring flow have as their fundamental insight that improvement of the systems and processes is not only possible but essential to healthcare leadership, as we lead ourselves and lead our teams.9

Figure 10-3: Solutions to Decrease Job Stressors and Increase Adaptive Capacity

One of the hardest things for leaders at all levels to accept is that a lot of the things we do in healthcare simply don’t make sense—either to the patient or to the people who take care of the patient. “Stop doing stupid stuff” is a way of harvesting “low-hanging fruit,” fixing problems that everyone can see but few have had the courage to correct. Most importantly, it creates hope that leaders are paying attention and are serious about creating a commonsense culture. There are countless examples of stupid stuff, including these:

Many mornings in the emergency department (ED), patients wait in line to be triaged when there are rooms, doctors, nurses, and essential services staff in the back waiting for them. They wait in a line when there should be no line.

Patients sit in waiting rooms for hours throughout the healthcare system, looking at a vision statement that proclaims, “Patient first.” Many of them have appointments but are still waiting for long periods. They can’t help thinking, “Really? Because I don’t feel ‘first.’”

Nursing units operate with fewer nurses than scheduled but are expected to produce top-decile metrics. They use the same systems and processes when “working short” that they use when fully staffed. And we are somehow surprised when they think, “Seriously? You know we need this level of staffing, but nothing gets done.”

A medical patient needs a physical therapy appointment before being discharged, which is identified as a rate-limiting step on rounds. However, instead of having a team member immediately call for the appointment, the team waits until rounds are completed before anyone calls physical therapy. By that time all the appointments for the day are taken and the patient cannot be discharged until the next day.

Patients “board” in ED hallways for hours (sometimes days) and are taken care of by ED nurses, who are thus unavailable to care for incoming ED patients. Once a bed is identified in the hospital, it takes hours to have it cleaned, and almost as long from the time it is cleaned until the inpatient team is ready to take the patient.

An orthopedic surgeon is on call over a busy holiday weekend, when there is a highly predictable number of patients with orthopedic problems who will require follow-up the next week. Instead of ensuring that there are a certain number of designated appointments for these patients, the surgeon’s schedule is filled, meaning the patients from the on-call schedule won’t be seen in a timely fashion.

One of the most critical rate-limiting steps in healthcare is the bottlenecks that occur in surgery, with delays between cases and surgeries requiring critical care unit beds “stacked” on days that create ICU overuse and backups for critical care patients admitted from the ED or transferred from other hospitals. Scientific surgical smoothing principles have not been applied to relieve the problem.

This list could go on, but each is an example of what appears to be stupid stuff, which we nonetheless continue to tolerate. The solution is to start doing smart stuff. Each of these problems can be fixed with relatively simple actions that change the systems and processes by which patients are cared for. Instead we create a culture where stupid stuff is tolerated. Leadership at all levels must seek out and resolve stupid stuff whenever and wherever it is identified. The first step for leaders to create a culture of hope and hardwire flow and fulfillment is to start doing smart stuff and start fixing stupid stuff. Fortunately, doing so sends a jolt of hope to the team, who think, “Well, I’ll be darned. Maybe they are finally serious about correcting things around here.”10

The impact on the staff of sending a signal of hope cannot be overstated. Team members are usually aware of the plethora of stupid things being done in the name of “That’s the way we’ve always done it.” When leaders begin to change these flawed systems and processes, it sends a signal of hope to the team that things don’t have to stay mired in the status quo ante, unleashing the huge potential of innovation and creativity.11

The Five Demand-Capacity Questions One of the key tools of hardwiring flow is the use of demand-capacity tools, including the five demand-capacity questions Jensen and I describe, which can also be used to allow us to understand patient demands, the expectations that accompany them, and the capacity to deal with them.2 By applying these questions in our work, we can increase our adaptive capacity by understanding the demand-capacity curve.2,12

1. Who is coming? (What are the demands?)

2. When are they coming? (What’s the timing of the demands?)

3. What will they need? (What is the specific nature of the demands?)

4. Will we have what they need? (What capacity do we have?)

5. What will we do if we don’t? (What is our adaptive capacity?)

Within each shift, these tools should be used to maximize adaptive capacity to the workload and the stressors the workload entails.

Emergency Departments as 24/7/365 Grafted on a 12–18/5/250 Hospital EDs work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year (24/7/365), which produces a workload that is predictable yet unrelenting. We can and should use the demand-capacity tools to inform us of who is coming and what they will need. But it needs to be recognized that the hospital does not, by nature, operate with all its resources, facilities, and staffing at the same level 24/7/365. Many of the resources needed to care for the ED’s patients—including MRI, consultative services, physical therapy, behavioral health services—are only available 12–18 hours a day, 5 days a week, 250 days per year (Monday through Friday, with holidays off or at limited staffing).13

CASE STUDY

Dr. Andrew Mathews and Nurse Ann Corrigan have worked the last three shifts in the ED together, starting with a day shift on Thursday. Today is Saturday and they are working the evening shift. On Thursday, they had a patient they cared for together, a 35-year-old lady with vague symptoms of chronic back pain, for which she had been seen multiple times, both in the ED and by an orthopedist. When Dr. Mathews examined her, he noticed a vague fullness in the paraspinal area and an equally vague sense that this area was warmer to the touch. At three o’clock that afternoon, he requested a gadolinium-enhanced MRI scan of the lumbar spine, which was performed within two hours and showed a spinal epidural abscess, which was drained in the operating room that evening.

It is now nine o’clock on Saturday evening and he and Ann see a 50-year-old lady with the acute onset of bladder incontinence and the beginnings of paresthesia in the “saddle” region. They suspect these could be early manifestations of spinal cord compression known as cauda equina syndrome, which, if present, is a neurosurgical emergency. Forty-five minutes later Dr. Mathews is informed that the MRI technician says that he must speak to the radiologist before the study can be done. He pages the radiologist, who doesn’t answer for another 45 minutes, but says, “Have you consulted neurosurgery to have them approve the MRI? We don’t do MRIs on the weekend unless neurology or neurosurgery approves them.” Dr. Mathews takes a deep breath and says in a measured voice, “Rodney, I would like you to take a moment and consider if this were your wife who had these symptoms, suggestive of the beginnings of spinal cord compression. Would you want us to jump through all these hoops and delay her care?” The radiologist approved the study, which indeed showed acute spinal cord compression. It was immediately decompressed surgically, and the patient made a full recovery, which might not have been possible if the MRI had been further delayed.

This case study reflects the details (except for the names) of actual cases, and it is a clear example of two standards of care—one for daytime, weekday hours and a second one for nights and weekends. As a result of the second case, despite its good outcome, a change was made in the policy for ordering MRIs, with a clear set of evidence-based protocols developed and approved by the emergency physicians, radiologists, neurologists, and neurosurgeons. The better the organization understands this demand-capacity mismatch and is prepared to deal with it by developing proactive strategies, the more their adaptive capacity increases.

Variation That Adds Value: Different Strategies for Different Realities

What is true in the morning is a lie by the afternoon.

CARL JUNG14

The concepts of hardwiring flow often stress reducing variation whenever possible, but the more penetrating insight is to recognize variation that adds value. For example, at ten o’clock on a weekday morning, the ED may use a process of “direct bedding” or “triage bypass,” in which patients are taken directly back to an ED bed instead of getting delayed at triage.15 But once the beds are all full, that process no longer works, and a different set of processes must be in place, including advanced triage orders for certain patients or, if beds will not be available for extended periods of time, physician or provider at triage.

Specialists in hospital medicine are familiar with the times of day when admissions come into the hospital, including the rates from the ED and from physician offices, as well as transfers. The best of them treat these patients expeditiously, often coming to the ED before all lab studies are completed, effectively working “in parallel” instead of sequentially. All of these are examples of teams prospectively understanding that in some cases variation adds value because the flow circumstances vary. This concept increases capacity in the face of increased demands (job stressors) and smooths workload.2,10,16

This case study is a clear example of how variation in flow patterns and demand-capacity principles drove a change in systems and processes during a single day in the ED. These principles apply across the healthcare system, where variation can add value.

REGAINING OR SEIZING CONTROL

In healthcare it seems that control over our daily lives has gradually been eroded, both for leaders and for all team members. When I speak to large audiences of healthcare leaders and providers across the country, I always ask them this question: “How many of you feel that you are held accountable for a system over which you have little or no control?”17

CASE STUDY

The ED team at Inova Fairfax Medical Campus were innovators in developing solutions to hardwire flow and fulfillment. Using data on arrivals and the five demand-capacity questions, teams of physicians, nurses, and essential services staff designed systems and processes to address each of the “flow realities” that occurred over the course of a typical day. In the mornings, there were available beds and staff, so the process known as “triage bypass” or “pull until you are full” was implemented, where patients went directly to open beds instead of waiting in a line to be triaged. When all the beds in the ED were full, the process needed to be different to meet the different circumstances. Advanced triage or advance initiatives were developed so the triage nurse could implement standing orders to begin the patients’ diagnostic work-up and begin the treatment for certain conditions. Later in the day, there were predictable times when the “boarder burden” of patients waiting for hospital beds caused delays because the ED beds were full. A system known as “team triage” was developed where an emergency physician, nurse, scribe, registrar, and technician were deployed to the triage area so patients could immediately be evaluated by the team and their diagnosis and treatment could begin. Over 30 percent of those patients were diagnosed, treated, and discharged without ever needing an ED bed. Both flow metrics and team and patient experience scores improved with each of these processes.

Unsurprisingly, every hand goes up. Each of these strategies helps regain control (Figure 10-4).

Scribes as Personal Performance Assistants One of the most consistent aggravations for physicians and nurses in EDs is the necessity of dealing with the EHR. The issues of EHRs and scribes are addressed in Chapters 8 and 11, but note that one solution to this is the use of scribes, or “personal performance assistants,” who are specifically trained and tasked with ensuring that the EHR needs are met, but that the physician’s or nurse’s interaction with the EHR is confined to value-added situations. This fundamentally changes the workload, freeing professionals to work at the “top of their license” instead of being glued to the computer screen.18–19

Practicing at the Top of Your License Practicing at the top of your license means that all team members work to the full extent of their education, training, and experience and are not forced to perform tasks that can easily be done by other team members with lower levels of training. It means that doctors do “doctor stuff,” nurses do “nurse stuff,” and so on through the team. Control is regained when systems and processes change to ensure that our skills, talents, and passion are harnessed to what we were trained to do. When staff at every level of the organization are surveyed regarding professional fulfillment, they universally and emphatically state that they want to spend their days doing work they are trained to do and not get bogged down with tasks and processes that could easily be done by those with lower levels of education and training.

Figure 10-4: Solutions to Regain Control

The use of well-trained emergency department technicians to perform EKGs, start IV lines, do discharges for patients with minor illnesses and injuries, and handle other tasks allows higher levels of fulfillment.20 In EDs with the best practices, it is rare for an emergency physician to suture a laceration, since the advanced practice providers not only are capable of doing this procedure but are also often better at it because they do it more often and do not have the same time pressures as the physicians. Over 15 years ago, I surveyed the senior, experienced nurses in our level 1 trauma center concerning which tasks they would be happy not to have to perform, and starting IVs was at the top of the list. Having technicians or EMTs working in the department take over those responsibilities increased satisfaction and fulfillment in both groups. Practicing at the top of the license is a way of hardwiring flow by decreasing the waste of doing a task that others could do equally well or better. It also is a more cost-effective means of resource utilization and efficiency for payers.21

Redesigning Systems and Processes with the “Takeoff” and “Landing” Approach One of the most powerful strategies to regain control is to ensure that all of our teams know that systems and processes are subject to constant reexamination and improvement. Further, each reexamination of systems and processes should be driven by the approach that “if they aren’t with you on the takeoff, they won’t be with you on the landing,” which is an essential component of regaining control.

REWARDS AND RECOGNITION

Rewards and recognition cut across all three dimensions of culture, personal resiliency strategies, and the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment. It is essential to hardwire gratitude, generosity, and thanks into our systems and processes (Figure 10-5). (Specific personal strategies are discussed in Chapter 8.)

Figure 10-5: Solutions to Increase Rewards and Recognition

Leaders Lead the Way in Saying Thank You It starts at the top—if healthcare leaders at all levels constantly exhibit the behaviors and language of thanks, the rest of the team will follow. Think of your most valued mentor. Didn’t she give you thanks often, which inspired you to do even better? Didn’t she see more in you than you saw in yourself? Didn’t she help you set guilt aside and thank yourself instead of being excessively self-critical? As Max DePree, former CEO of Herman Miller, says, “The first responsibility of a leader is to define reality. The last is to say thank you. In between, the leader is a servant.”22

The best place to say thanks is at the bedside or in the work environment, where the praise was earned and others can witness it. One of the most enduring ways for a leader to say thanks is vastly underused but always deeply appreciated: a brief handwritten note. I use four-by-six-inch notes, which require brevity and clarity but also fit into a pocket quite easily. I have found that many people do just that, carrying a note with them at work to keep it close for inspiration during challenging times. The paper I use simply has a name at the top, no titles, which stresses that it is a personal note, not from “the boss” but from a person who is thankful to work with you. What do you write in the note? Just open your heart and write that in the note. No need to overthink it. When should you write it? Whenever you think of it. Leaders should treat rewards and recognition as a discipline, as a regular part of the day. Just as you should say thanks every day on leader rounds and in the course of your work, you should also return from rounds, sit down, pull out at least one card, and think, “Whom do I need to thank today for doing a great job? To whom am I particularly grateful today?” President George H. W. Bush was a prolific note and letter writer, not because it was a leadership tool or PR trick but, as he said, “because that’s how I was raised and because it made me feel better.”23

Reward Yourself We will never be fully able to reward and recognize others unless we can accept rewards and recognition ourselves. It is a curious phenomenon that many healthcare professionals, who have chosen their careers to serve others, nonetheless are sometimes reluctant to serve themselves through self-recognition of a job well done.24 In designing and redesigning systems and processes, look for subtle opportunities to build rewards and recognition into them. Hint: anytime we transition service from one person or system to another, there is an opportunity to give rewards and recognition, as I will discuss next.

Seams of the Team and Harvesting Compliments One of the most important insights in hardwiring flow is the importance of adding value and eliminating waste during the service transitions of healthcare. An equally important insight is that there are far more service transitions in healthcare than we often realize. I’ll discuss this in more detail in “Passing the Baton,” but as leaders look at systems and processes, they should look for the “seams of the teams,” which are the seams of transitions, and find ways to ask, “How can we build thanks, rewards, and recognition into each of them as a standard way of operating?”25 One of those ways is by “leading up” through language.

Leading Up or Managing Up A critical leadership tool to hardwire flow and fulfillment into systems and processes is a concept I have referred to as “leading up” or, as the Studer Group refers to it, managing up.26 “Leading up” or “managing up” refers to empowering others by using verbal service transitions to ensure the patient is led to expect excellence from the person or groups who will next care for the patient. While the primary benefit of leading or managing up is that it prepares the way for a smooth service transition from one person and one service to another, it also serves to “lead up” the person to whom care will be transferred in that it helps them to understand that a great deal will be expected of them, given their superb introduction to the patient and family.

The following are some examples:

• “Janet is your nurse today, and she’s the best.”

• “Jim is the orthopedic technician, and he will put your splint on and teach you to walk with your crutches. He’s actually better at this than I am.”

• “Let me introduce you to Dr. Smith, my partner, who will be taking over for me. I have briefed him on all the details and he will take great care of you.”

• “The x-ray shows that your bone is fractured, so I spoke with your physician, who recommended I call the orthopedic surgeon. His name is Dr. Theiss and he will be in to take care of you soon. He is excellent and will do a great job!”

• “As I said earlier, we will need to admit you to the hospital today, so I have called your doctor, who asked that we admit you to one of our hospital specialists in hospital medicine. Dr. Gonzalez will be admitting you today and will keep your doctor informed of your care every step of the way.”

Making Thanks Mandatory Makes Thanks Easy It seems that giving thanks, rewards, and recognition should be the easiest thing on the planet, doesn’t it? Why is it so rare in our daily lives, particularly in healthcare? As you approach your day, closely observe your teams. Do they thank each other often or rarely? Which is more commonly heard, “Thanks, that was a great job,” or “Why did you make that mistake?”? On balance, is there more praise or blame in your day? The ratio of praise to blame is the inflection point between burnout and fulfillment.

“Making thanks mandatory” doesn’t necessarily have the ring of a servant leadership culture. But if rewards and recognition are a part of “the way we do things here,” saying thanks becomes the norm, not the exception—and it makes it easier to say thanks. The more the team does it, the more they will reconnect to their passion.

RETURNING COMMUNITY TO THE TEAM

We can confidently assure that in healthcare, you will be taken care of by a team of experts. But we can less confidently assure that you will be taken care of by an expert team.

THOM MAYER27

Healthcare is, by nature, a team sport—it can only be provided by a group of people who work together for a common goal. That said, a team is not a group of people who simply work together; it is a group of people who trust each other while they work together. The primary teamwork goal of leaders seeking to hardwire flow and fulfillment to battle burnout is to foster and develop trust among the team members and to exhibit language and behaviors to engender trust.

In addition to the foundation of trust, teams in healthcare share a definition and a set of teamwork skills (Figure 10-6).27

Teams and Teamwork Skills and Training Teams have four fundamental characteristics. First, they have a common sense of clearly defined purpose that the team had a role in generating (“takeoff” and “landing”). Clarity of purpose is essential to flow. Second, trust and a deep sense of respect for all team members and the unique roles they play is a core aspect. Third, hardwiring flow and fulfillment focuses on ensuring there is a system of value-added processes, with a focus on the “seams of the teams” during which transitions occur. Finally, there must be a culture of celebration of team success while providing individual coaching and mentoring.27

Figure 10-6: Solutions to Restore Teams and Community

Fortunately, in addition to this definition, there is a set of time- and experience-tested tools of teamwork (further discussed in Chapters 17 and 18):

• making the patient part of the team

• hire right!

• the seams of the teams

• dyad/triad leadership

• mutual accountability

• a culture of coaching and mentoring

• anticipation

• demand-capacity leadership

• empowerment

• high-reliability organizations

• reliable and redundant communication

• clinician huddles

Passing the Baton Jensen first pointed out to me that at the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, the US men’s 4 × 100-meter relay team comprised the best athletes in the world—some say it was the best relay team in the history of the sport. Their goal was clear: to win the gold medal. Their path was also clear: to advance through successive rounds to the finals. They were the best individual athletes in their sport, so much so that it was difficult to decide which order to run them in, since the anchor, or final runner, is usually the fastest. Did they win the gold medal? No, they did not. In fact, they didn’t make it out of the quarterfinal round. Why? They dropped the baton.

At that level of sport, with athletes that good and that experienced, this may seem hard to believe. But it was not a failure of the athletes but rather a failure of coaching. They had been coached to run fast individually. But the goal of a relay team is to run fastest as a team. These were good men who had trained their entire lives to reach the pinnacle of the Olympic Games—but the team had been assembled only a relatively short time before the Olympics. Perhaps if the coaches had them spend more time on the baton passes, the results would have been quite different.

The point is that leaders must recognize the multiple service transitions that necessarily occur in healthcare—the passing of the baton and the seams of the teams. In healthcare, perhaps the “baton” that is being passed is our patients.3,9 When we figuratively drop them by not focusing on the handoffs, we not only fail to serve them well, but we also inadvertently create burnout among the “great athletes” forming our teams. Coach your teams to “pass the baton well,” not just to attain individual results.

Physician and Nurse Transformation An important transformation is under way in healthcare in which physicians, as well as nurses, are moving from a position of authority to being a part of a team in partnership with the patient and family. In the past, physicians were expected to be authoritarian, authoritative sources of wisdom and knowledge to whom patients came for answers to their needs. Of course, they were also expected to be compassionate caregivers. Osler’s wisdom was always correct: “It is better to know what sort of patient has the disease than what sort of disease the patient has.”28

The transformation among physicians and nurses also includes placing them in roles as “chief experience officers” and “knowledge translators.” Physicians and nurses are the primary determinants in the creation of a positive experience for their patients, which means they need to be not only excellent clinicians but also experts at creation of the experience for the patient and the family, which combines the art and the science of medicine and nursing.

While the authoritarian models of the past placed an expectation of almost encyclopedic knowledge and wisdom on the part of the nurse-physician dyad, today patients are so well informed in many cases that doctors and nurses effectively become “knowledge translators” whose role it is to make sense of the data and interpret its meaning for the patient and family, integrating what the data have shown into an understandable whole.

This transformation can be a source of frustration and therefore burnout if it is not understood, embraced, and anticipated. It redefines how the team acts as a community in this new environment. If this is understood, it can help create a new sense of community and teamwork, preventing burnout.

Huddle Up: Using Clinical Huddles to Reinforce Community Chapter 19 discusses the role of clinical huddles in creating teamwork in healthcare. These huddles develop shared mental models29 by which community is reinforced on a regular basis, as well as delineating specific contributions that will be made by team members for the good of the patient. They also ensure that the entire team interacts and prevent people from working in relative isolation through the course of the day. And they create common understandings among the team members, further reinforcing community.

Rounding on Next Rounding is an important tactic within the organization that ensures that information is shared across boundaries and communication is enriched. It owes its origins to the concept of “management by walking around,” originally described by Tom Peters and Robert Waterman in In Search of Excellence and further examined by Peters in The Excellence Dividend.30–31 The rounding concept should be extended to “rounding on next,” which refers to rounding on patients admitted from the ED to the hospital.32 Keeping a log of patients each physician and nurse admits and having them visit the patient on the inpatient unit has incredible value in helping them understand their important role in the healthcare community. It is also deeply appreciated by the patient and family, increasing gratification and preventing burnout. An additional way to “round on next” is to place follow-up phone calls to discharged patients. While this has clear value in reestablishing community, it is less effective than the face-to-face interactions of rounding on inpatients.

Figure 10-7: Solutions to Rebuild Fairness

RESTORING FAIRNESS IN AN UNFAIR ENVIRONMENT

Healthcare team members are driven by a profound belief that what is provided to their patients should be eminently fair. While some refer to this as healthcare equity, in the trenches it comes down to a tacit determination of “Is this fundamentally fair to the patients and to those who take care of the patients?” (Figure 10-7).

Conduct a Bounty Hunt for Unfairness and a Treasure Hunt for Fairness As much as values are critically important to preventing burnout, the domain of fairness is where burnout in healthcare is often first noticed. Because of the deeply egalitarian nature of physicians and nurses, it is not surprising that this is the case. However, focusing on fairness also has tremendous leverage on reestablishing the team and leadership’s commitment to fairness, equity, and parity, both for the team and for its patients.9 Look at each aspect of hardwiring flow and fulfillment and every system and process. For each, conduct a “bounty hunt” for unfairness and eliminate it. Have a “treasure hunt” for fairness and celebrate it.

Mutual Accountability and the Language of Fairness Eliminating functional silos33 and ensuring there is mutual accountability across boundaries is a clear way of ensuring fairness, since many people “say ‘team’” but don’t “play ‘team.’”27 Mutual accountability involves eliminating statements such as, “Well the physicians’ patient experience scores are great. It’s the nurses’ scores that are pulling us down.” Instead, an approach that is focused on fairness uses language such as, “We are all in this together. Let’s see what worked in raising the physician scores and see if we can apply that in other areas.” Accountability across boundaries is essential to creating transparent fairness, as well as team trust.

The language we use also reinforces both community and fairness. Examples include the following:

• “That was an excellent job!”

• “You just saved this guy’s life!”

• “Thanks! You made a B-team day into an A-team one.”

• “What could I have done to make your job easier?”

• “Anne picked up some very important information that is going to improve your care.”

• “Isaac is our best advanced practice provider. You’re fortunate he’s here.”

The more this language is used—and used across boundaries—the more evident fairness will be. A core concept in fairness is ensuring that the B-team members are held accountable for their actions, language, and behavior. Failing to do so massively erodes trust in leaders, since the team feels, “There are two sets of rules here—one set of rules for the B-team members, who ‘get away with it,’ and a second set of rules for the A-team, who are held accountable.”32

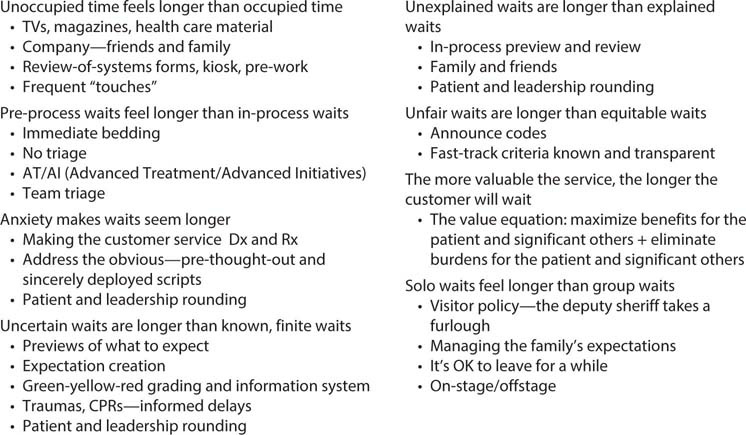

Putting the Psychology of Waiting to Work One of the things that seems most unfair to patients is how long they are forced to wait in healthcare. Most people consider time to be one of their most valuable assets, so wasting time is not only rude and unconscionable, it also wastes a valuable asset that cannot be recaptured. Jensen first pointed out to me that the psychologist David Maister recognized there is science behind how waiting can be managed in an effective fashion.34 Hardwiring flow and fulfillment requires designing systems and processes to minimize waiting when possible and to use the skills listed in Figure 10-8 when they can’t.

RESTORING VALUES INTO THE WORKPLACE

Very few things cause more moral dilemmas resulting in burnout than situations where team members witness the contrast between stated values and actions that are diametrically opposed to those values. It has been my experience that the more focused and pristine the stated values, the more potential for actions that don’t fit those values. Values like “Patient first” and “Patient always” are excellent, clarion calls to action, but leaders who seek to hardwire flow and fulfillment should constantly reexamine processes and systems to assess how they reflect those values (Figure 10-9).

Constantly Apply the “Connect Systems and Processes to Values” Test At each level of the healthcare organization, leaders at all levels should ask these questions:

• How does this system or process actively reflect our stated values?

• If it doesn’t reflect those values, what changes need to be made to correct that?

Figure 10-8: Putting the Psychology of Waiting to Work

Figure 10-9: Solutions to Restore Values

• Who will be responsible for those changes?

• When should we expect the changes to occur?

• How will we know the changes have reconnected our values to the systems and processes?

• Do these systems and processes promote a “passion reconnect”?

Regardless of the model of change or performance improvement used, these questions are essential.

All Change Is Tied to Values The only constant in healthcare is change, and we find ourselves in the “perpetual whitewater of change.” Having an organizational and a personal change strategy is a core element of battling burnout. Imbedded in those change efforts should be a constant view toward how each change reflects—or contradicts—the values we embrace.

In Every Action, Encourage Team Members to Be Able to Say, “Yes, This Embodies Our Values” Systems and processes are the cauldron in which values are reflected, but so are the actions, behaviors, and language of the individual team members who enact them. Team members should be encouraged to continually reassess not only how to hardwire flow and fulfillment but also how their own actions embody those values.

“Nothing about Us without Us” One of the bedrock elements of “making the patient a part of the team” is the principle of assuring the patient we are committed to the ideal of “Nothing about me without me.”35 Leaders should extend that concept to apply to every team member in making changes to the system. Far from being disruptive, it conveys to team members that their input will be sought, that input will be considered, and the team writ large will follow the new system in service to its values.

Summary

• Hardwiring flow means building into systems and processes the ability to add value and reduce waste during the patients’ journey through our healthcare systems.

• Hardwiring flow and fulfillment means starting to do “smart stuff” (which adds value), ceasing to do “stupid stuff” (which creates waste), and “fully filling” our passion by burning in instead of burning out.

• Solutions to hardwire flow and fulfillment should be grouped according to Maslach’s 6 domains.

• Constantly test whether your systems and processes reflect or contradict the stated values.

• All change must be tied to values. Do the changes provide a path to “passion reconnect”?