6

A Model for Change and Mutual Accountability

Making shots counts. But not as much as the people making them.

MIKE KRZYZEWSKI, DUKE MEN’S

BASKETBALL COACH AND WINNER OF

FIVE NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS

AND THREE OLYMPIC GOLD MEDALS1

A Model for Change and a Scorecard for Success

To conduct an assault on burnout, we need an effective model with which to frame the problem and a scorecard to monitor successes and the reasons for them. Our model starts with the assumption that the sources of burnout as a mismatch between job stressors and the adaptive capacity or resilience to deal with those stressors are twofold:

• personal factors (lead yourself)

• systemic/organizational factors (lead the team)

The journey begins with us since the work begins within. As personal transformation occurs, people are inspired to transform the culture and the systems and processes embodying the work we do. As noted previously, much of the current literature on burnout focuses on personal factors and how to improve personal resilience. But doing so exclusively ignores the critical role that our current culture and system have in producing burnout in the first place. More importantly, too much of the work to date has implied—if not explicitly stated—that we are the problem, instead of advocating the cultivation of personal resiliency by investing in the people themselves and not in what they can do for us.

Systemic/Organizational Factors: Culture and the Hardwiring of Flow and Fulfillment

The organizational factors producing burnout include the culture of the healthcare system, as well as how effectively flow and personal and professional fulfillment are hardwired into the system.

I will define each of these elements shortly, but for now, let’s simply focus on the role they play in producing burnout and the ways in which they can be changed to prevent or treat burnout. Culture and hardwiring flow + fulfillment are organizational resilience, or “creating the job you love,” in the burnout equation.2

Personal Factors: Reigniting Passion and Personal Resilience

The power to reignite passion on a personal level cannot be overstated, which is why I start with “Lead yourself.” It is by changing the way we’re working at the systemic and personal levels that passion can be reignited and reconnected to purpose. Personal resilience is the foundation for the solution, but it is incomplete without changing culture and hardwiring flow and fulfillment—all three are needed for success. “The work begins within” and that work fuels us in making changes to the culture, systems, and processes.

The Model for Changing Burnout and Driving Fulfillment: Three Core Elements

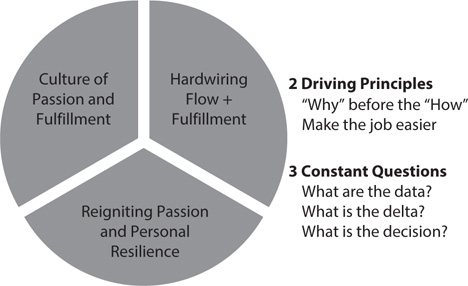

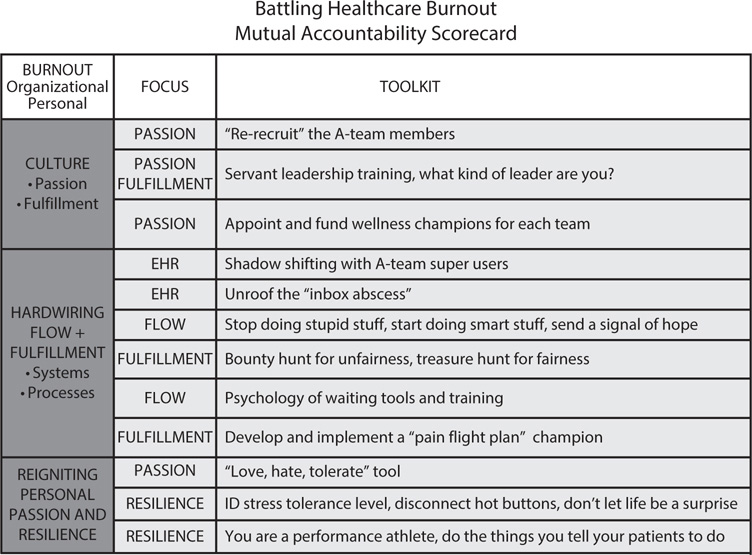

These observations provide a framework of three core elements (Figure 6-1):

• creating a culture of passion and fulfillment

• hardwiring flow and fulfillment (systems and processes)

• reigniting passion and personal resilience

Figure 6-1: Three Core Elements of Addressing Burnout

Figure 6-2: The Model for Decreasing Burnout and Increasing Fulfillment

This model demonstrates that culture, the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment, and personal passion and resilience are inextricably linked, with fully two-thirds of the burnout equation coming from how we work, and only about a third coming from personal issues. However, as I have noted, the best results occur in health systems that begin with facilitating personal resilience while working to change the culture and the system.

Let’s consider how these three core elements combine to change the landscape of burnout and its solutions while maintaining an emphasis on getting the “why” right before the “how” by using intrinsic motivation and the three constant questions (Figure 6-2). Combining these concepts creates the solutions discussed in Chapters 8–11, and the Mutual Accountability Jumbotron, which is discussed later in this chapter. This model provides a way to track progress toward the dual goals of systemic/organizational resilience and personal resilience, both of which increase the adaptive capacity of the system and the person to deal with job stressors.

CULTURE OF PASSION AND FULFILLMENT

The first core element is that the people and the systems and processes exist in an organizational culture, which must be based on passion and professional fulfillment. Regarding the successful transformation of that company, Lou Gerstner, former CEO of IBM, said, “I came to see in my time at IBM that culture isn’t just one aspect of the game, it is the game.”3

Culture is what people do in an organization, not just what they say they do. But it goes beyond that. It’s also how people think—particularly how they think about change, improvement, and innovation, since those thoughts will change what they ultimately do. These insights are critical when considering burnout because the culture in which healthcare is provided will be quickly discerned by those providing the care. They know, before those in the C-suite do, when the “words and the music don’t match.” Here’s a simple example, born from experience with the electronic health record (EHR).

CASE STUDY

Tamara Ellis is a highly rated and sought-after internist who specializes in hospital medicine, one of the fastest-growing specialties in healthcare. Her hospital introduced an EHR and mandated its use immediately. Unfortunately, the selection of the vendor was made without input from the line clinicians who would be using the EHR and was almost exclusively driven by the IT department. (To be fair, there were physicians on the committee, but none of them actively practiced medicine and they were widely referred to as “former physicians.”)

Following the roll-out of the EHR, Dr. Ellis’s productivity and patient experience scores fell dramatically. She became, in her own words, “more frustrated, cynical, and less effective.” When she met with her service chief and expressed her frustration, he said, “That’s just the EHR. You have to learn to live with it!” Shortly thereafter, she resigned her position to enter a concierge medicine practice, depriving the team of one of its “superstars.”

There are many lessons to learn from this tale, but I will focus primarily on the culture of the organization for now. Let’s start with the two driving principles:

1. “Why” before the “how”

2. Does it make the job easier?

In this case study, the “why” of the EHR appears to have been, “Because the boss says you have to do it.” There was no serious consideration of involving clinicians in either the design or its implementation. As to the second question, far from making the job easier, it makes the work demonstrably harder, without consideration or explanation.

What other lessons can be gleaned from Dr. Ellis’s experience and the culture in which it occurred? First, it illustrates that the organization does not have a change strategy in which those most affected by the change have a voice in the change itself. (If they aren’t with you on the takeoff, they won’t be with you on the landing.) In this culture, change is mandated from above. Second, the culture of the organization is siloed and does not take into account the fact that healthcare is a complex, adaptive system, where change in one area has predictable effects on others. Third, IT rules the roost in this culture, and the people caught up in the turmoil of the EHR change are left to fend for themselves. This is a culture where the people serve the EHR, not the other way around. (I will present solutions to Dr. Ellis’s dilemma in Chapters 8 and 11.) Finally, despite what is proclaimed in the organization’s mission, vision, and values, the culture in action is one where those providing care are treated as fungible instead of indispensable, even high performers like Dr. Ellis.

Culture in a Complex, Adaptive System Culture is continuously redefined and honed over time, and in response to a constantly changing landscape. The ability to develop the culture adaptively is perhaps the truest test of leadership.4 Leaders who believe culture is fixed are doomed to failure, while leaders who see culture as an ever-adapting entity that reflects what actually happens, as influenced by a core set of values, can help guide their organizations forward.

Chapters 8–11 address how to use a matrix of questions to assess culture, the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment, and personal resilience, but here are some topline questions that help assess whether “the words and the music match” regarding culture:

• Is the person you report to passionate about their job?

• How, specifically, is that manifested?

• Does their passion help fuel your passion?

• Do they manifest behaviors that exemplify the culture?

• Do they demonstrate a commitment to their own wellness?

• Do they demonstrate a commitment to the team’s wellness?

Words on the Walls versus Happenings in the Halls Chris Argyris notes that there is a fundamental difference between the “espoused theory,” the theory promoted by leadership and management, and the “theory in action,” which reflects how the organization actually operates.5 Every healthcare system should carefully examine how closely its espoused theory matches its theory in action. What are the actions occurring in the interactions with each patient? Stated another way, pay attention to the “happenings in the halls instead of the words on the walls.”6 As lofty and noble as statements of mission, vision, and values can be, the true test is whether the “happenings in the halls” reflect those statements. Far too often, they don’t and in some cases are diametrically opposed to the stated mission. Emerson said it well: “What you are stands over you and thunders so loudly I cannot hear what you say.”7

In sharp contradistinction to the administrator in the previous case study, this CEO put the “why” of patient care ahead of the “how” of all the reasons it had never been done before. And the Boarder Patrol concept clearly made the job easier for the team—and improved the experience of the boarder patients. An essential part of the Boarder Patrol was using data on the number and types of boarders, the “delta” between the number of boarder hours and the target, and the concept empowered the morning huddles to make immediate decisions to reduce the boarder burden.

CASE STUDY

When I was the chairman of emergency medicine at a level 1 trauma center seeing over 100,000 visits a year, the emergency department (ED) was plagued by a massive “boarder burden,” in which it was common to have one-third to one-half of the beds occupied by patients who had been admitted to the hospital but were waiting up to 12–18 hours to be placed in an inpatient bed. In the midst of one of our worst boarder days, I had a scheduled appointment with our CEO, Steve Brown.

Steve was a true “roll up his sleeves” executive who prided himself on exemplifying a lead-from-the-front style. I called Steve and said, “Boss, we need to do a ‘walkie-talkie’ today” (which meant that, instead of meeting in his office, we needed to walk and talk our way through the ED on rounds, a signature part of his leadership style). Instead of seeing statistics on boarder hours, Steve saw and met the patients boarding in the ED hallways.

We came to an 85-year-old lady, whose 92-year-old husband sat patiently at her side in a metal chair. Instead of just moving on, Steve insisted I introduce him. Once I did, he said, “Mrs. and Mr. Smith, my name is Steve Brown and I am the CEO—I run this place. I am so sorry this happened, but I promise you I will get you a bed and make sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else in the future.”

Steve was as good as his word and put the “Boarder Patrol” concept in place, which made the administrator on call responsible for meeting all boarders, whatever the time of day or night, to assure them they would get personal attention—and a bed.

This is as good an example as I have ever seen of making sure that the “words on the walls” match the “happenings in the halls.” Without a commitment to a culture of passion focused on professional fulfillment, supported by timely patient rounding, Steve couldn’t have heard Mrs. and Mr. Smith’s voices. This story resonated through the halls of our medical center, proving that the leader meant what he said. Unfortunately, the opposite is also true far too often, as the following case study shows.

Based on these observations, I had to report that the organization’s espoused theory wasn’t matched by its theory in action—indeed, quite the contrary. What I observed was a persistent, pervasive demeaning pattern of interaction, which directly resulted in low team engagement, high rates of burnout, and low patient experience scores. This is an example of how a negative culture and the failure to hardwire flow and fulfillment produce frustrating—but predictable—results.

CASE STUDY

I was asked to work with a hospital’s executive team, which had high aspirations for excellence and at least a “words on the walls” commitment to teamwork in service of a “through the patient’s eyes with a servant’s heart” mission. Despite their goals and stated commitment to hearing the voice of the patient, they were falling short and staff engagement surveys had turned downward in a dramatic fashion. After spending a week with the team, including watching them and their direct reports in meetings, on phone calls, and in the hallways, I was sorry to have to report this summary of what I observed:

• constant interruptions in meetings, a proclivity to debate instead of develop consensus, and a willingness to engage in confrontation that bordered on delight

• deep commitment to one’s own proposed course of action instead of the team’s

• inherent frustration in the inability to get a point across, regardless of how well reasoned and supported by data

• a “win at all costs” attitude that would have made Coach Vince Lombardi look like an amateur

• a tendency to interrupt the patient or family regularly in the uncommon instance in which an executive did round on patients

• communication that was nearly always one-way—a lot of talking, almost no listening

How to Move from the “Words on the Walls” to the “Happenings in the Halls” Once the difference between the “words on the walls” and the “happenings in the halls” is understood, how do we change this calculus to benefit the team?8

• Recognize it: Be clear in noticing the “delta” between what is said and what is done. Encourage others to do the same.

• Name it: Make sure the team understands this language and is attuned to it.

• Delineate it: State precisely what the disconnect is between the mission, vision, and values and the theory in use. Give examples.

• “Data, delta, decision” it: Use this format to drive the discussion down to the details.

• Resolve it by revisiting it: Constantly revisit the issue until it is resolved.

HARDWIRING FLOW AND FULFILLMENT: SYSTEMS AND PROCESSES THAT ADD VALUE, MAXIMIZE EFFICIENCY, AND DELIVER EFFECTIVE RESULTS

The second core element is assuring that all systems and processes are hardwired for flow and professional fulfillment by adding value, decreasing waste, maximizing efficiency, and delivering effective outcomes.

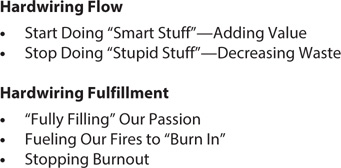

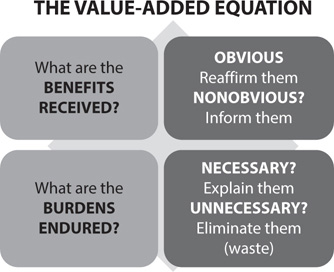

Defining and Creating Value My colleague Kirk Jensen and I coined the term hardwiring flow and wrote a book titled Hardwiring Flow: Systems and Processes for Seamless Patient Care,8 designed as a practical guide to using an evidence-based, lean approach to improving flow in healthcare. We defined flow as follows: “Flow is defined as adding value and decreasing waste as our patients move through our service, processes, or behaviors by increasing benefits, decreasing burdens, (or both) when moving through our service transitions and queues.” Simply stated, hardwiring flow means to “start doing smart stuff” that adds value, and to “stop doing stupid stuff” that creates waste. Flow and fulfillment are inextricable. We cannot attain fulfillment unless we hardwire systems and processes for smart stuff while eliminating stupid stuff (Figure 6-3).

While some definitions of value stress that it is a ratio of healthcare outcomes divided by the cost of providing those outcomes, such formulations are not practical in assessing and delivering bedside care, particularly since “costs” are difficult to define, poorly understood, and largely beyond the control of those providing the care. What is the cost of an abdominal CT scan for a patient with abdominal pain? How does that relate to the outcome? What is the value of the abdominal CT relative to the number of negative CT scans necessary to identify one positive scan? How consequential does the CT finding have to be to be considered of value? How does any of this help doctors and nurses provide bedside care?

Very few people can hazard a guess as to the “cost” of an abdominal CT. Some might say, “Perhaps $3,000–$4,000?” But even if that number were accurate, that is not the “cost” of an abdominal CT. It is, at best, the “charge” for the procedure. (The marginal cost—the cost to do one more CT once the equipment and team members are in place—is nominal, perhaps a few hundred dollars. But the charge is many times that.)

Figure 6-3: Hardwiring Flow and Fulfillment

Figure 6-4: The Benefit-Burden Ratio

Faced with these dilemmas of costs versus charges and trying to define outcomes in financial terms—which may well work in the macroeconomics of healthcare—we proposed a different definition of “value at the bedside”: Value is a ratio of the benefits received divided by the burdens endured to receive that value in the provision of quality care (Figure 6-4).8

For a nurse or doctor at the bedside, this is a ratio that can be not only understood but also used to pragmatic effect for the good of the patient.

Value in Abdominal Pain A 32-year-old female presents to the ED with right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. She has had two similar episodes of pain, but this is much worse. What value can her physician and nurse offer?

Aside from whatever broader equation is used for calculating value, the nurses and doctors in the ED can offer significant benefits with relatively few burdens endured to this patient almost immediately, including the following:

| Benefits Received | Burdens Endured |

| Pain relief | Pain of starting the IV |

| Nausea and vomiting relief | Time to administer the meds |

| Rapid IV hydration | Time to obtain studies |

| Reassurance of the diagnosis | Anxiety until the diagnosis is made |

| Timely and efficient diagnosis | Several hours in the ED |

| Radiology and lab expedited | |

| Reassurance to the family |

This calculus of the benefit-burden ratio can be understood and used by the bedside caregivers—it doesn’t require a PhD in healthcare economics to calculate value. Pain relief and stopping the vomiting are examples of obvious benefits, but they should still be reaffirmed with this language:

Your pain is likely coming from a gall bladder problem, but we can stop it with medication that works quickly and effectively, which I’ve asked the nurse to get for you. Your vomiting is coming from the same source, so he will get you a tablet you can put under your tongue, which works even faster than the IV route.

Patients with nausea and vomiting are also dehydrated, which makes both the pain and vomiting worse. That is a nonobvious benefit, about which the patient needs to be informed, using scripts:

Ma’am, it’s been my experience that people with pain and vomiting are dehydrated, which I confirmed by observing how dry your oral mucosa area is. We’ll give you some IV fluid to “fill your tank” and the nurse will draw your blood at the same time so we don’t have to stick you twice.

The burden of anxiety can be eliminated early in the course of care:

Based on your symptoms and your physical examination, this is very likely due to your gall bladder, which is where your pain is, in the right upper area of your abdomen. When it goes into spasm, it can be quite painful and causes vomiting. In addition to the medications and IV fluid we are giving you, our team will bounce some sound waves off that area to see if the gall bladder wall is thickened or if there are stones in there, both of which are evidence of cholecystitis. You also have some “crackles” in your lung base over here, which are probably due to not breathing quite as deeply due to the pain, but since your pregnancy test was negative, we would like to do a chest x-ray just to make sure there isn’t an infection. Does that all make sense? What questions do you have?

An example of a necessary burden is the time needed to obtain the laboratory and imaging studies to confirm the diagnosis, which is a burden that should be explained. One of the best ways of doing that is a technique I learned from my colleague Ralph Badenowski from St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Jacksonville, Florida, which led to me to refer to it as “Badenowski’s Law.”9 It is a way of letting the patient and the family know that while they may spend several hours in the ED to obtain the studies to confirm or delineate the diagnosis, that time actually has a significant value compared with other settings in which the work could be done. Here’s what Badenowski says to explain how the patient is getting “10 days of work done in about 4 hours”:

Ma’am, we will take care of your pain and vomiting as fast as we possibly can, but the lab and radiology tests will take us about four hours to complete. But that’s a real value where you get about 10 days of work done in about four hours, because, as you know, you didn’t have to make an appointment to see me, you came right down to the ED. Many people wait several days to get an appointment with their doctor. And if you had pain in your doctor’s office, they wouldn’t be able to get the lab and radiology studies quickly like we can. You have to make an appointment and that takes several more days. We get the results of those studies within 30 minutes—you would have to wait a few more days to come back to the doctor to do that. So it will take about four hours, but we’ll get 10 days of work done!

Badenowski’s Law is a way of explaining obvious burdens to help create value from the patients’ viewpoint. If burdens are unnecessary, they constitute waste and should be eliminated. For example, until recently, many radiologists and surgeons demanded that oral contrast be given to ED patients before obtaining abdominal CT scans, which delayed the study by as much as two hours per patient. However, except in limited circumstances, oral contrast was shown in numerous studies to be an unnecessary burden and was eliminated from the protocol, saving time, money, and discomfort for the patient.

Using the benefit-burden ratio to define value in healthcare drives decisions to the bedside, as well as encouraging the use of scripts as evidence-based language to help patients see the value they are receiving.

Using evidence-based disciplines to define value has three discrete effects:

1. It provides an actionable way to define and provide value at the bedside, by increasing benefits and decreasing burdens.

2. It leverages value as personally delivered through team actions tied to the systems in which that value is delivered.

3. It makes the job easier for the team by providing evidence-based disciplines by which to hardwire flow.

The third point is why I use the “hardwiring flow and fulfillment” formulation—because evidence-based, team-generated systems and processes to improve flow make the job easier and leverage the likelihood that professional fulfillment will be enhanced rather than diminished. If we are all collectively committed to adding value by increasing benefits and decreasing burdens, as well as eliminating waste, we are creating systems and processes of seamless care—good for the patient and good for those caring for the patient. When we hardwire flow through evidence-based leadership, we are also hardwiring fulfillment for those who provide the care.

Maximizing Efficiency and Delivering Effective Results The distinction between efficiency and effectiveness has been the source of debate and controversy. Archie Cochrane, in his book Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Service,10 offers guidance on this subject. The fundamental question of effectiveness is simply, “Does it work?” In Cochrane’s words, efficiency refers to the effect of “a particular medical action in altering the natural history of a particular disease for the better.” This simple yet practical definition involves two parts:

• Does the action have a demonstrable effect? = Effectiveness

• Is the effect better? = Efficiency

Efficiency asks, “Is ‘what works’ worth the cost?” In this case, the cost is a calculus of dollars, time, and the effort requisite to produce the intended outcomes.

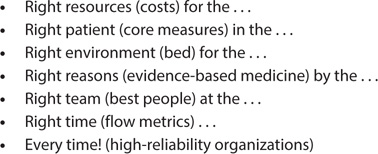

Figure 6-5: Flow and the “Seven Rights”

Jensen and I combined effectiveness and efficiency into the ability to use flow to produce the “Seven Rights” in healthcare, shown in Figure 6-5.

The right resources ensure that only the costs necessary are applied to the problem, whether clinical or administrative. The right patient ensures that core measures are used to define what measures will be used to gauge success. The right environment means that the MVP of the healthcare system, the bed, is used to the best advantage, and only for as long as the bed adds value.8 The right reasons are the evidence-based protocols, open to iterative change as further evidence develops. The right team ensures that all those involved in the patient’s care are operating at the top of their license and are best deployed to add value. The right time means that flow metrics are in place and monitored over time, so that flow, effectiveness, and efficiency are maximized. Finally, every patient, every time is an embodiment of the commitment to patient safety and high-reliability organizations. All of these “rights” are critical to both best outcomes and preventing burnout.

John Wasson at Dartmouth expressed this eloquently when he said, “They give me exactly the help I need and want exactly when and how I need and want it.”11 For those who think this an ambitious goal for all of healthcare, I ask this question: “If that were you, your spouse, your children, your mom or dad, your neighbor on that bed, isn’t that precisely what you would not only want but demand?”

We must confess that the answer is “Yes!”

But the issue is not just whether we deliver value while maximizing efficiency and delivering effective results but also what the cost is—from the standpoint of stressors and the care providers’ resilience or adaptive capacity to deal with those stressors. Does hardwiring flow and fulfillment enrich or deplete our teams and team members? One test of this is this question: “Are leaders willing to change processes and systems so their teams can stop doing ‘stupid stuff’ and start doing ‘smart stuff’?” Are we able and willing to stop doing things we shouldn’t be doing in favor of those things that are better for the patient—through the patient’s eyes—while making the team members’ jobs easier? A resounding “yes” gives hope we can reduce burnout and accelerate fulfillment. To “stop doing stupid stuff” requires the courage to state clearly that the ways we have been doing things aren’t working … or at the very least aren’t working well enough. That’s the price of leadership.

REIGNITING PASSION AND PERSONAL RESILIENCE

While culture and the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment form the systemic/ organizational sources of burnout and the resilience needed to combat it, the ability to reignite passion and develop and use the tools of personal resilience are the final third. This is the “learning to love the job you have” part of the equation. Chapter 8 covers this in detail, but the key is to use the six domains of burnout, as defined by Christina Maslach, as a format for building and maintaining personal resilience.12

• Diminishing stressors and increasing adaptive capacity: The domain of diminishing stressors is connected to changing culture and hardwiring flow, while increasing adaptive capacity develops both organizational and personal resilience.

• Seizing control: Seizing control starts with the personal and moves quickly to the organizational once the tide is turned, as we’ll see in Chapters 8–10.

• Giving and getting rewards and recognition: Giving rewards always starts with the individual and stays with the individual, but it does redound to the broader culture.

• Returning community to healthcare: Community is a complex mix of individuals (and their resilience) coming together to form the broader culture and the systems and processes in which the community works.

• Demanding fairness in an unfair world: Fairness resides everywhere, all the time. If the system or those acting within the system act unfairly for one person, unfairness exists for all people. Fairness connects to all three core elements of burnout.

• Infusing values into your practice: This starts with individuals committing to their values in every action—including in leadership positions; their combined commitment to values defines the culture and hardwires flow and fulfillment.

A “Jumbotron” for Mutual Accountability

Success requires reporting efforts to address the three core symptoms of burnout, stating the effects on metrics for success, and noting progress made in the “data, delta, decision” format, all while using intrinsic motivation. Whether it is called a “Balanced Scorecard,”13 “Pillar Management,”14 or any of the other terms for the myriad ways of keeping score, measurement of important things matters, while measurement of trivial things does not—and the measurement of trivial things demoralizes and burns out those measured. Practicing medicine in the NFL is what I call “jumbotron medicine”—everything is up on the big screen for the entire stadium and all the viewers worldwide to see. (Before every Super Bowl, I meet with the team physicians, trainers, support medical staff, and referees. I always tell them the same thing, “Relax—there’s only 80 million people around the world watching you.”) It sometimes feels the same with our scoreboards in healthcare—everything measured is magnified, particularly when the metrics go south.

Begin by ensuring that those being measured have input on what is being measured. Be willing to toss out metrics that do not themselves add value by providing leverage in the “data, delta, decision” conversation. Make data conversations iterative—change data collection or data points in response to the changing needs of the complex adaptive system.

Keep in mind this wisdom: “What you permit, you promote.”15

When systems, processes, languages, and behaviors contradict the “why” of the organization, leaders need to be courageous in correcting them. Otherwise, the team knows not only that the B-team has “gotten away” with it again but also that these behaviors are promoted when they are permitted to occur again and again. Figure 6-6 shows how the jumbotron can be used with the three core elements and three constant questions to monitor the progress of action plans. This is described in more detail in Chapter 10.

The best jumbotron for burnout answers the three constant questions for each of the three core elements as they pertain to the area of focus. Using the examples in Figure 6-6, here is how the format can be used.

Culture of Passion and Fulfillment

Area(s) of Focus |

Three Constant Questions |

Passion/re-recruit A-team Data? |

Turnover of A-team Delta? Difference between actual and target Decision(s)? Specific actions to re-recruit |

Figure 6-6: Jumbotron for Mutual Accountability

Hardwiring Flow and Fulfillment

Area(s) of Focus |

Three Constant Questions |

Flow/treasure hunts for value, bounty hunts for waste |

Data? Flow metrics, benefit-burden ratio Delta? Difference between actual and target Decision(s)? Stop doing stupid stuff; start doing smart stuff, send a signal of hope |

Reigniting Passion and Personal Fulfillment

Area(s) of Focus |

Three Constant Questions |

Passion; love, hate, tolerate tool |

Data? Burnout, resiliency, turnover Delta? Difference between actual and target Decision(s)? Accentuate “loves”; minimize “tolerates”; eliminate “hates” |

Summary

• The model to address burnout involves three elements:

1. Creating a culture of passion and fulfillment

2. Hardwiring flow and fulfillment through systems and processes

3. Reigniting passion and personal fulfillment

• The first two concern organizational resilience, while the third concerns personal resilience. All three are necessary to recognize, prevent, and treat burnout.

• Be aware of the trap of “the words on the walls” not matching “the happenings in the halls.”

• Flow is defined as adding value and decreasing waste as our patients move through our services and processes by stopping stupid stuff and substituting smart stuff.

• Value is defined as a benefit-burden ratio, where value is increased as benefits increase, burdens decrease, or both.

• Flow depends on seven “rights”:

1. Right resources (costs) for the …

2. Right patient (core measures) in the …

3. Right environment (bed or facility) for the …

4. Right reasons (evidence-based medicine) by the …

5. Right team (best people for the specific job) at the …

6. Right time (flow metrics) …

7. Every time!

• The Mutual Accountability Jumbotron is needed to monitor progress.