8

Sustaining Personal Passion and Resilience

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.

VICTOR FRANKL, MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANING1

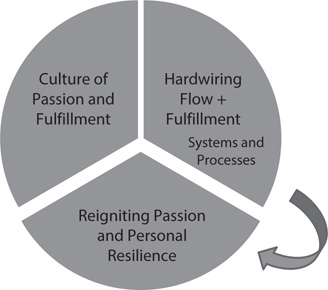

Reigniting Passion and Personal Resilience

Healthcare team members are artists, scientists, leaders, and tellers of the great stories of our patients. Our burning passion is to step into the lives of those we serve, in the hope of making those lives better or at the very least easier. The following two chapters focus on organizational resiliency (changing the situation), while this one, in Frankl’s words, addresses the challenge “to change ourselves.” The Stoic philosopher Hecato of Rhodes remarked, “What progress have I made? I have begun to be a friend to myself.”2 Beginning to be a friend to ourselves is an essential corollary to understanding that the work begins within.

In focusing on reigniting passion and personal resilience, two central ideas serve as the foundation:

1. Every member of the healthcare team is a leader and needs personal leadership skills to do their jobs. Lead ourselves, lead our teams.

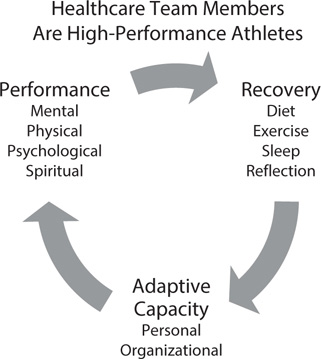

2. Every member of the healthcare team is a high-performance athlete, no less than the men and women at the highest levels of sport, and they thus require the same principles of performance, rest, and recovery. Invest in ourselves, invest in our teams.

All of us have a responsibility to “work on ourselves.” That work takes different forms for different people but shares many common aspects that fuel our values and further our passion. This chapter focuses on strategies to reignite passion and personal resilience. As Tom Peters so eloquently notes, “You are the CEO of ‘Me, Inc.’”3 Make sure you are investing in yourself by reigniting passion and personal resilience—that will increase the shareholder value of “Me, Inc.”

An important word of caution: even if your organization lags behind in doing its part to develop organizational resiliency, now is precisely the time to redouble your efforts to develop your personal adaptive capacity, since you will need it to deal with the job stressors of an organization not yet fully committed to increasing its resiliency.

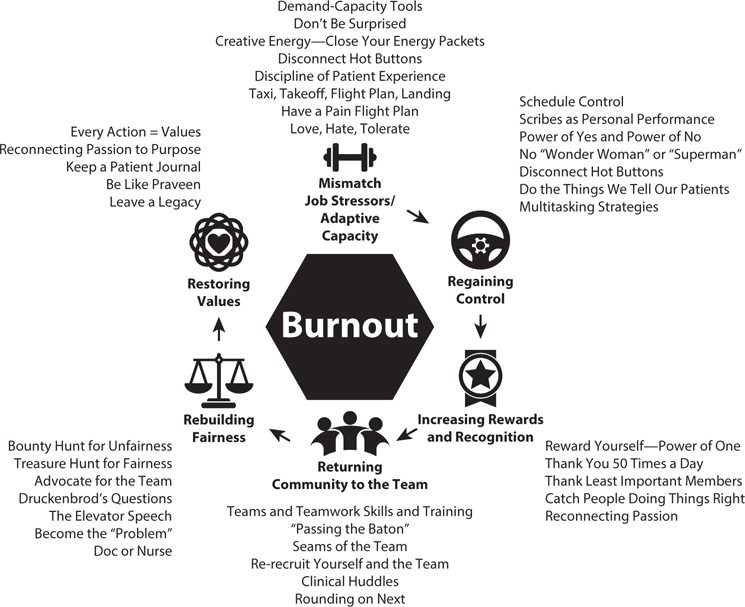

However, what works magically for some people may not work at all for others. For example, pursuing “mindfulness” is one strategy discussed here that is commonly advocated as a solution to mounting stressors and burnout.4 For some of you, it is an appealing strategy and one that you may have been considering or are beginning to pursue. For others, the response might be, “Oh no—not that ‘touchy-feely’ stuff again. If one more person tells me to be ‘mindful’ I’m going to scream.” Given the breadth of background and interests of the members of the healthcare team, it’s not surprising that one size never fits everyone. Without being encyclopedic, I have tried to share whatever solutions have been proved to have value by numerous healthcare sources. As in other chapters, I have classified these solutions according to how they best fit into the six Maslach domains.5 However, six solutions cut across all the domains and are therefore presented first. These solutions are listed here, and the domains and the rest of the solutions associated with them are shown later in Figure 8-1.

• deep joy, deep needs

• throw guilt in the trunk

• make the patient part of the team

• precision patient care

• chief storyteller

• strategic optimism

Solutions across All Domains: The “Big Six”

Six solutions cut across all of the domains and should be used by all team members, regardless of where or what work they do. They are all leadership skills requisite for the demanding work of being a leader in healthcare.

Figure 8-1: Solutions to Reignite Passion and Personal Resilience by Maslach Domain

DEEP JOY, DEEP NEEDS

In the Introduction and Chapter 4, I briefly mentioned that I told our three sons each day when they were younger as I dropped them off at school that it was “one more step in the journey of discovering where your deep joy intersects the world’s deep needs.”6 The consistent message to our sons was to begin with their “deep joy” as opposed to the “world’s deep needs,” since all of us must discover what we enjoy doing, where we enjoy doing it, the kind of people we want to share the journey with, and the circumstances under which all of this occurs. “Deep joy” is simply the passion that fuels you. Once you know that, the rest of the “world’s deep needs” are simply details to be filled in over time. You can’t give what you don’t have, and you can’t know what you have until you discover your deep joy.

Closely related to the concept of “deep joy, deep needs” is the importance of relationships, connectivity, and trust to health and happiness. Bob Waldinger is the fourth director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development. While that might sound a bit dry, it is the world’s longest and most intense study of what makes people happy over time. In what are also known as the Grant and Glueck studies, since 1938 Harvard has been intensely studying 258 members of the Harvard sophomore class and 456 men from the Boston inner city to determine what factors were most responsible for health, longevity, and happiness. (As Waldinger notes, the men from the inner city always ask, “Why do you want to study me? My life isn’t all that interesting.” Waldinger observes, “The Harvard men never ask that question.”)7–8

Among the many insights from the study, the two most powerful ones are these:

• Loneliness kills—it kills not just happiness but health and longevity as well.

• The single strongest predictor of happiness and a “good life” is having good relationships built on trust.

Everyone in healthcare whom I hold in esteem is someone I trust—and they trust me.

When job stressors grow and your adaptive capacity is thinning, reach back and rediscover your “deep joy.” Chapter 17 discusses how to use the “deep joy” tool to do just that.

THROW YOUR GUILT IN THE TRUNK—LIGHTEN UP ON YOURSELF

We need to find a cleaner-burning fuel than guilt.

RICHIE CANTOR, PEDIATRIC EMERGENCY

PHYSICIAN AND TOXICOLOGIST9

Cantor is an expert on toxins. He also knows that among the most lethal of those toxins is guilt, which can extinguish passion in a flash if we let it. I ask people how they get to work and most answer, “I drive my car.” I answer, “Do me a favor—next time you go to work, before you go in, open your trunk and throw all your guilt in there. Because it won’t help you in any way when you are inside.” This is a delicate balance, because as I’ve said before, guilt weighs heavily on those who admit they are burning out; they think they are too strong—or should have been—for that to happen. Nearly all victims of burnout think, “I can’t believe I burned out—I thought I was better than that.” We must all recognize that there’s no shame in burnout. Leave the guilt behind; it only weighs you down.

The first step to throwing guilt in the trunk is recognizing it for what it is. Guilt comes from many places but almost always has its origins in how we grew up. There are always places deep in the psyche or soul that to this day cause us to feel badly. Face, trace, and erase them. The second step is to forgive yourself, regardless of how serious you feel your real or perceived transgressions may be. Remember, as Wayne Sotile, a pioneer in the study of physician burnout, says, “Self-care is critical care.”10 And yet most of us were taught that self-care was selfish. Third, remember that almost without exception, the events from which guilt arises weren’t as bad as you remember. Or as Mark Twain wrote, “I have known a great many troubles, but most of them never happened.”11 Fourth, recall that “when you’re in your own mind, you are behind enemy lines.”12 We would never judge others nearly as harshly as we have learned to judge ourselves. In fact, if we saw someone being that judgmental, most of us would confront that person and say, “You can’t treat her that way—it’s unfair.” Don’t treat yourself that way either.

Tom Jenike, the chief well-being officer at Novant Health, one of the nation’s leaders in physician and team well-being, often says, “We have to be World Class at caring for ourselves and our team members so they can be World Class at taking care of our patients.”13

MAKING THE PATIENT A PART OF THE TEAM

One of the tools that helps build personal resiliency the most is the concept of making the patient part of the team, which I introduced in Chapter 1 but is briefly summarized by these three points:

• Shift from asking “What’s the matter with you?” to “What matters to you?”

• That helps move the patient from being a recipient of care to being a participant in their care.14

• The voice of the patient means, “Nothing about me without me.”15

A constant focus on these areas makes the patient a part of the team and increases our personal adaptive capacity.

PRECISION OR PERSONALIZED PATIENT CARE

The concept of precision or personalized patient care, also described in Chapter 1, is another of the powerful tools to increase personal resiliency. As an emergency physician practicing in a 120,000-annual-visit, level 1 trauma center, I practice precision patient care by realizing that no two patients are alike, even with something as straightforward as an ankle sprain. That starts with always asking the same question of each patient: “What’s the most important thing to you we can do to make this an excellent experience?”16

Precision patient care allows team members to tailor their care specifically to the person behind the disease, instead of focusing on a “one size fits all” approach. While the technical, clinical care may be the same for some patients, the precise way in which their care is managed after the diagnosis is made is at the core of precision patient care.

This is also true in diagnosing, preventing, and treating burnout and is much more than a theoretical distinction. For example, if a person’s burnout symptoms reflect feelings of loss of meaning in work, should the presumption be made that treatment should focus only or largely on that aspect, or should it automatically be presumed that the patient had to have progressed through exhaustion and cynicism to get to loss of meaning in the first place? All three of the dimensions occur early, if differentially, in each person, and the treatment needs to be tailored to the needs of the person’s burnout symptoms, based on surveys and open-ended conversations, as I discussed in detail in Chapter 7.

CASE STUDY

One evening, I saw a 15-year-old female lacrosse player with an inversion injury of her ankle. I performed a careful evaluation, during which I explained everything that I was doing, as well as the anatomy of the ligaments and bones of the ankle and first-, second-, and third-degree sprains. Although a fracture seemed unlikely, I described why we were obtaining an ankle radiograph.

When the radiograph was completed, I pulled the computer on wheels into the room, sat down, and demonstrated to the athlete and her family that the images confirmed my clinical diagnosis. I told them we would be discharging her soon and that she would be on crutches for several days and would need rest, ice, compression, and elevation during the next week. Asking what questions she had, I thought she was overreacting when she burst into tears.

It was then that I realized I had forgotten to use precision personalized care and had not asked, “What’s the most important thing to you that would make this a great ED visit?” When I did ask that question, she told me she was a recruited athlete, the state championship was in four days, and several college coaches were going to be there to scout her. Playing in that game was the most important thing to her. I felt foolish. While I had made the correct clinical diagnosis, I had failed her by not considering what this injury meant to her.

I learned late, but not too late, what was most important to the patient and was able to arrange aggressive cold compression treatments, physical therapy sessions with the local professional team, and ankle taping by an athletic trainer. She was able to play in the state final in front of numerous women’s college lacrosse coaches … and me.

CHIEF STORYTELLER, CHIEF SENSEMAKER

Reigniting passion and personal resiliency in healthcare requires the fundamental recognition that nurses and physicians have a nondelegable role as the “chief storytellers” for the patient and family.17–19 I believe there is no greater way to reignite passion and personal resilience than to control the narrative of your patients’ care by accepting the dual roles of chief storyteller and chief sensemaker.

Patients come to hospitals and healthcare systems because their lives are disrupted by pain, injury, and many other symptoms that they do not fully understand. Nurses and physicians have the role of the chief storyteller, who tells the story that otherwise the patient and the family may not fully understand. Doctors and nurses explain their symptoms and tell them the story of how the team will use diagnostic tools and studies to determine the etiology and devise the most effective treatment.

CASE STUDY

When our middle son, Kevin, was nine years old, I came home from work and found him nose deep in his literature homework. He asked whether I could help him. I read the passage carefully, thought for a minute, and told him what it said. His response was, “Dad, I know what it says. What does it mean?”

However, we not only need to tell patients the story of their care; we need to act as chief sensemakers as well. The chief storyteller tells the story of the symptoms, the diagnosis, and the proposed treatment, while the chief sensemaker integrates “the big story into the big picture.”

If we want our patients to understand what their healthcare means, we must incorporate sensemaking into our storytelling. Sensemaking is layered over storytelling and provides the context of meaning. Sensemaking means navigating healthcare by means of a compass instead of a map. (And it is wise to recall Count Korzybski’s caution that “the map is not the territory.”)20 The best compass is making the patient a part of the team so they can guide the journey with you. Karl Weick said it well when he noted that successful leaders capture both the big picture and the big story: “To lead in the future is to be less in thrall of decision-making and more in thrall of sensemaking.”21

Reigniting passion comes from “guiding the journey” of patients and explaining what will happen to them through their healthcare peregrinations. That said, the story—and the sense we make of it—is always mutually discovered, a journey that is never one-sided but rather is cocreated by the team and the patient and their family.

STRATEGIC OPTIMISM

Are you an optimist or a pessimist? (Or a realist?) Do you see a glass half-full or half-empty? That test is often used to guide assessments of optimism versus pessimism. (Shortly before he died, I asked my father, known affectionately to everyone as “Grandpa Jim,” that question. He thought for a moment, smiled, and answered, “It depends upon whether you’re pouring … or drinking.” It is always about perspective.)

Several years ago, I developed a concept known as strategic optimism,22 which is the principle that life’s greatest asset is our capacity for optimism, the ability to assess a situation and invest it with the most positive practical possibility. (There are many other definitions, but that is mine.) Since it is an asset, we should maximize the return on investment (ROI) to ensure we use it wisely and well and increase its “wealth.” Despite our preconceptions, none of us have unlimited energy—and none of us have unlimited optimism, so it must be used wisely.

CASE STUDY

John Brown and Julie Broussard are both hospital medicine physicians in a level 1 trauma center with high volume and acuity. Long waits and delays are a daily occurrence for their patients, and hospital boarders range from 10 to 15 per day. The hospital has invested millions of dollars in a new electronic health record (EHR), with little advance training or support of the rollout.

Frustrations are extremely high among all the team members, including Dr. Brown and Dr. Broussard. Dr. Brown has chosen to spend a great deal of time complaining about the EHR, the boarders, and the stresses placed on him by administration to perform at a higher level. Recently, he vented these frustrations to a patient who complained about the long wait, saying, “Take it to the CEO—she’s in charge here.” When a nurse asked him whether he was being pessimistic, he said, “Why be pessimistic? It would never work.” (And, no, he wasn’t trying to be funny—he simply didn’t understand the irony in his remark.)

Dr. Broussard has taken another approach by first admitting that the EHR is not going away, so she and the team would be wise to develop strategies to work with it and not against it. She volunteered to chair a task force charged with doing just that. Recently when the chief operating officer was rounding and asked about the boarders, she replied, “Thank you for coming to see us. I feel so badly for these patients and their families who wait for hours to days in the hallways on stretchers for a bed upstairs. And I’m concerned about our nurses, who are overburdened already and who are at risk for burnout if we can’t work together to solve this problem. May I introduce you to Mrs. Woodyard? She’s been waiting the longest for a bed upstairs. I’m sure she would love to hear your perspective.”

Both Admiral James Stockdale and Senator John McCain were naval aviators during the Vietnam War whose planes were shot down, resulting in their being incarcerated for years at the “Hanoi Hilton.” Both of them said it was their experience that the people who died first in that brutal environment were the “blind optimists,” meaning the people divorced from reality who constantly felt they would be liberated “quickly, soon, or even the next day.” They had not invested their optimism wisely, squandering it on an unreasonable belief, ungrounded in reality or reason. Stockdale called on what he described as “brutal optimism”: “I never lost faith in the end of the story. I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end, and turn the experience into the defining event of my life. This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse the faith that you will prevail in the end with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality.”23

To reignite passion and personal resilience, start with brutal optimism—a realistic assessment of the situation, confronting the “brutal facts of your current reality.” Write those facts down. Now turn to the “faith that you will prevail in the end” to illuminate how you can invest your optimism to maximize your ROI. This is strategic optimism—since your optimism has boundaries and limits, use it to your strategic advantage by placing it in the right places at the right times for the right reasons for the maximum effect.

Both Dr. Brown and Dr. Broussard are extremely intelligent and talented physicians who are respected for their clinical acumen. But Dr. Brown has chosen to approach problems with a victim’s mentality, believing that these problems are happening to him, and choosing to rail against the problem instead of finding solutions. He has chosen to adopt a negative leadership style, bathed in pessimism.

Dr. Broussard has chosen to invest a difficult situation with strategic optimism, choosing her words and actions to leverage a tough situation toward the most positive practical possibility. On self-evaluation, which doctor rates their energy level and attitude higher? Which one is rated extremely highly by the nursing team as a preferred physician with whom to work? Who is trending toward better scores on burnout and engagement indices? We all know it is Dr. Broussard, who has rejected a victim’s mentality for the strategic optimism option. Her approach is not bathed in pessimism but is buoyed by hope.

Chandy John is a pediatric pulmonologist who wrote a thoughtful essay on her concept of “constructive worrying,” defined as worrying only about those things that matter most and making positive and proactive plans.24 Constructive worrying can be considered a corollary to strategic optimism in that it focuses worrying only on ways to improve, learn, forgive yourself, and then move forward. As she says, “So in fact, it’s not just OK to worry, it’s good to worry.”

We all recall Hippocrates’s dictum, “Primum non nocere” (First do no harm). But how many of us recall that the very next words are “Deinde benefacere” (Then do some good)?25 Strategic optimism and constructive worrying help increase our personal resiliency by focusing on the good to be done.

As you assess your levels of the cardinal burnout symptoms of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and a loss of meaning in work, where will you strategically invest your optimism? Will you invest it wisely, or will you squander it on false hopes and unreasonable expectations? And remember: the more wisely you invest your optimism, the more optimism you will have because of the ROI.

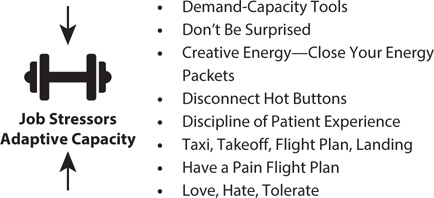

Solutions Focused on the Six Maslach Domains

Since the symptoms and consequences of burnout arise from a mismatch between increasing job stressors and the adaptive capacity to deal with those stressors, a critical part of the burnout solutions is to decrease the stressors, while increasing the adaptive capacity to deal with them.

Figure 8-2: Solutions to Decrease Job Stressors, Increase Adaptive Capacity, or Both

DIMINISHING WORKLOAD DEMANDS AND INCREASING ADAPTIVE CAPACITY

Several highly specific strategies diminish workload demands, increase the adaptive capacity to meet those demands, or do some combination of both simultaneously (Figure 8-2).

Using the Demand-Capacity Tools Personally While I will discuss the use of the five demand-capacity questions to hardwire flow and fulfillment in Chapter 10, these questions can be helpful in reigniting personal passion and resilience or adaptive capacity.26

1. Who is coming? (What are the demands?)

2. When are they coming? (What is the timing of the demands?)

3. What will they need? (What is the specific nature of the demands?)

4. Will we have what they need? (What capacity do we have?)

5. What will we do if we don’t? (What is our adaptive capacity?)

In fact, I teach my residents and fellows to tell their patients, “We knew you were coming—we just didn’t know your name.”27 This has several positive effects that increase personal resilience. First, it tells the patient that you have dealt with patients with their clinical problem and thus have experience with it. Second, it puts them at ease to know they have come to the right place with the right problem. Third, by saying “we” instead of “I,” it communicates the team nature of the care they will receive.

For those in office-based practices where the appointments are known in advance, make time to review the schedule and put some thought into how you will approach those patients. Let them know you are happy to see them: “I was so pleased when I saw your name on the schedule today. It’s good to see you. How have you been doing?” These tactics decrease job stressors by lowering anxiety and increase adaptive capacity. They are closely related to making sure you aren’t surprised when you go to work.

CASE STUDY

Jon Myers has been the administrative director of a busy emergency department (ED) for 15 years. Nearly without exception, the ED is overcrowded, has multiple boarders, and has waits longer than he would like. He recently told me, “I have some staff—doctors and nurses—who have worked here as long as or longer than I have. Every day they come to work—mornings, afternoons, and nights—and it’s always the same. Yet they look around and think, ‘Where did all these people come from?’ They’re surprised. I’m surprised that they’re surprised. How can they be surprised when that’s all they see, all day, every day for the past 10 years?”

Don’t Be Surprised Workload and adaptive capacity to deal with that workload are dependent on what we are prepared for as we approach our work. The good news is that, with some exceptions, most experienced physicians and nurses have an innately informed sense of what they will see during a typical day or night at work. Don’t let work be a surprise—reflect on the way to work on the number and types of patients likely to be seen, what their likely expectations will be, and how best to positively and proactively care for them.

Don’t let your work life be a surprise to you—think about what you are likely to see, the challenges you will face, and the tools and energy you will need to get through the day. You will need every ounce of your creative energy to get through the day.

Creative Energy—Close Energy Packets One of the most powerful personal solutions to reignite passion and personal resilience, known as “gaining creative energy by closing your energy packets,” is also related to strategic optimism. One factor that determines workload demands and the capacity to deal with them is the amount of energy required to meet the demands (stressors) versus the energy available to you while at work (adaptive energy capacity). Just as exhaustion is an element of burnout, energy is the bellwether of passion and engagement. Joan Kyes, a registered nurse, had a wonderful concept she called “creative energy,”28 which allows people to creatively invest their energy by completing tasks in a timely fashion, thus returning the energy so it can be used for other projects. Everyone knows someone who seems to have an inexhaustible energy reservoir—they are always ready to take on the next challenge—whereas those who are burned out always seem to have nothing left in their energy reservoir.

Kyes made the point that all humans have basically the same energy reserves and that when we take on a project, we take an “energy packet” out of the tank, with the size of the packet varying based on the magnitude and complexity of the requisite work needed to complete it. However, the energy expended on the task or project does not return to the energy reservoir until the task is fully completed. Thus, people who seem to have low energy levels have multiple “energy packets” out and open, depriving their energy tank of being refilled until those tasks are completed. Chapter 17 discusses how to use this tool.

Taxi, Takeoff, Flight Plan, Landing As a result of serving as the command physician at the Pentagon on 9/11, I have had several opportunities to observe naval aircraft carrier operations. On one of those trips, I had an epiphanic moment in which I realized that caring for patients is like performing carrier operations in that there is a discrete taxi, takeoff, flight plan, and landing:

• Taxi: Prepare to go into the room to see the patient, but with all pertinent information available before doing so.

• Takeoff: This is the most thrilling part of a flight and the first chance to make a great impression, so introduce yourself professionally and with energy to let them know you are pleased to be their doctor or nurse.

• Flight plan: Just as the F/A-18 pilots on the carrier know their flight plan for each mission, we need to know the “flight plans” for the most common clinical entities we will see in a day, including abdominal pain, chest pain, trauma, pediatric fever, hypertension, and well-child checks, all of which should reflect evidence-based team approaches, not just to clinical care and patient safety but to patient experience as well.

• Landing: Nailing the landing is key for aviators and for healthcare team members, so we need to prepare for how we will handle them.

More in-depth approaches are in Chapter 17, but remember that the workload is easier when we have well-developed and mutually shared approaches to patient experience.

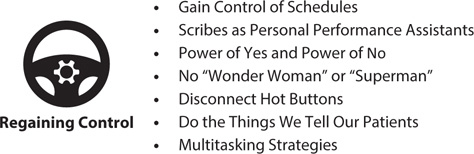

REGAINING OR SEIZING CONTROL

Experience across many healthcare systems and all members of the team indicate that being held accountable for areas over which they have too little or no control is a major driver of burnout. Figure 8-3 lists solutions to regain control, which are discussed below.

Figure 8-3: Solutions to Regain Control

Gain Control of the Schedule One of the areas where we feel loss of control is in the schedules we are required to work. Healthcare systems are realizing how important this is and have developed creative scheduling, such as self-scheduling, surge shifts, split shifts, and scheduling for circadian rhythms.29 Take advantage of these opportunities where they exist and advocate for them where they don’t. This is an important part of regaining control.

Scribes as Personal Performance Assistants: “Doing as Documenting” In several chapters, I have discussed solutions to the many stressors created by the necessity of dealing with the EHR, as well as the solutions needed to develop adaptive capacity to deal with them. One of those is the use of scribes, who should be viewed not just as individuals who record appropriate information but also as personal assistants who make the job easier in other ways. This includes enacting the concept of “doing as documenting.” Imagine if doing the work were somehow magically translated into the medical record by the very act of performing it.

The “Power of Yes” and the “Power of No” to Regain Control Rob Strauss emphasizes the importance of “the power of yes,” which recognizes that acknowledging a person’s thoughts and feelings is not the same as agreeing with them or with the solutions they propose.30 Tom Jenike, who developed and implemented the award-winning Novant Leadership Development Program described in Chapter 12, is often referred to as “Doctor Get to Yes” because of his similar focus on positive language and behavior.31 “Yes” builds strength and trust without acquiescence. For example, if a patient requests an MRI scan of their knee at three o’clock in the morning for chronic pain, a typical response might be, “No, we don’t do that study at three in the morning.” Not only is the patient’s request denied, but it is denied in a negative way, starting the interaction with “no.” However, a more positive approach is to say, “Yes, I can understand that you would like to get the scan done immediately. However, for problems like yours, we’ve found that getting your physician’s approval and coordinating with insurance actually ensures you aren’t responsible for any unnecessary costs.” The power of yes helps the workload by proactively using effective language to manage expectations.

Conversely, “the power of no” recognizes that we often take too much work on instead of reflecting on how the task fits with the others already on our plate or in the queue. Saying, “I would love to help, but I have to say no this time out of fairness to the other commitments I’ve already made.”

No “Wonder Woman,” No “Superman” Closely related to the power of no is the recognition that none of us are—or should try to be—superhuman action heroes, capable of accepting any and every challenge presented to us. First, it is unhealthy and frankly unnatural to take on all the world’s work and make it our own. Second, while subtle, it bespeaks an arrogance that is ultimately unhelpful and can damage relationships if taken to an extreme, as if we are capable of things “normal human beings” are not.

When you notice, “Wow, I have a lot on my plate,” be sure you show the maturity and common sense to say, “I would love that challenge and I am so pleased you thought of me, but I wouldn’t be able to give the effort needed right now to do it justice. But please ask me another time and if I can help, I will.” Show the self-awareness to know you are reaching your stress tolerance level, as discussed in Chapter 2. Most of us don’t need a to-do list—but we do need a “to-don’t” list.32

Disconnect Hot Buttons Everyone has “hot buttons,” but not everyone knows what they are. If you don’t know, ask the people you work with. Hot buttons are situations, types of interactions, or types of patients that get an involuntary, seemingly uncontrollable response from us that is invariably negative. Those responses increase our workload and reduce our resiliency, and they should thus be avoided. Leaving your hot buttons connected, particularly when you are experiencing symptoms of burnout, adds massive—and unnecessary—stress precisely when you cannot afford it. Chapter 17 discusses how to disconnect your hot buttons.

Do the Things We Tell Our Patients to Do Doctors, nurses, advanced practice providers, and other members of the healthcare team are extremely good at both proscribing things patients should not do and prescribing precisely what they should do. Are we following the same proscriptions and prescriptions for ourselves? The evidence is that we do not, which contributes to the epidemic of burnout.33–34

Recovery in High-Performance Healthcare Athletes The concept of recovery following high performance has strong scientific data to support it, as well as a massive body of experience in elite athletes.35–37 However, recovery should also be used with members of our healthcare teams. The word recovery derives from the fourteenth-century Anglo-French term rekeverer, which means to return to health or a previous stable condition.38 Modern sports science has clearly shown that effective recovery not only returns us to our previous stable state but also can increase performance over time, an important part of which is resiliency or adaptive capacity in all performance dimensions (Figure 8-4), including the following:

• mental

• physical

• intellectual

• psychological

• spiritual (connectedness, mindfulness, reflection)

Figure 8-4: The Cycle of Performance, Recovery, and Resilience

Properly understood, recovery has the potential to go beyond the prior state to a higher level of performance in each of these dimensions.38 Drew Brees, who holds the NFL records for most passing yards and touchdowns, once told me,

Doc, I am constantly committed to using whatever happens to me to get better. When I tore the labrum of my throwing shoulder when I was with the Chargers, there were plenty of people who told me my career was finished. I didn’t think so and more importantly, the Saints didn’t think so and I used every day of rehabilitation to improve. I still do that, every day, every play. As I tell my 3 boys every day, have an attitude of gratitude, humility, and respect and if you work hard enough at something you love, you can accomplish anything.39

While the physical toll of playing professional football is well known, the combined mental, physical, psychological, intellectual, and spiritual stress of working in healthcare is both cumulative and considerable. We need to use the principles of recovery to recharge, replenish, renew, and restore. The principles of sports science and recovery have made dramatic advances over the past 20 years, best summarized in the work of Mark Verstegen, the director of performance for the NFL Players Association, founder of EXOS, and the originator of the concept of core performance. EXOS’s in-depth work on recovery is available free of charge on the company’s website. It is common to hear, “This stuff is actually fairly simple.” That is right, and as Verstegen says, “Simple things done savagely well.”40

Breathe Of the things we take for granted in our lives, breathing is the most important and the most neglected. Obviously, it is the first step in oxygenating our tissues, but the way in which it is done can make a huge difference in performance and recovery. The children’s book Dinotopia captures it well: “Breathe deep–achieve peace.” How often did our parents tell us, “Take a deep breath”? It not only gives a moment’s reflection but also allows tense muscles to relax and the rib cage to expand, increasing vital capacity. There are myriad ways to use breathing to perform and recover (including yoga breathing),41–43 but two I find helpful are “6-4-10” and “6-3-6” breathing. “6-4-10” means to assume a comfortable position, then, while focusing on your breath, inhale for a full 6 seconds, hold it in your lungs for 4 seconds, then gently exhale for a sustained 10 seconds. Repeat this five times. I do it immediately after awakening, just before going into work, any time I encounter a stressful situation, and again at the end of the workday before I go home.

“6-3-6” breathing is a valuable tool for helping you prepare for sleep, as the shorter hold and exhalation prepares you for rest, not action. Do it 10 times and you will feel more restful. Invest some time in using your breath to your advantage.

Eat There are over 10,000 books telling you what, when, how, how often, and what not to eat, so I will only make a few points here:

• Do not skip breakfast. Without fuel, you are running an engine inefficiently and without the energy you need to do the hard work of healthcare.

• Think ahead. Part of the reason people end up eating junk food is that they haven’t thought ahead to plan what and when they will eat. Take healthy meals and snacks (however you choose to define those) to work with you.

• Use food as a performance tool, not a reward.

• Eat colorfully. Make sure there are at least three colors per meal—that likely means you’re getting the vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants you need. (And different colors of M&Ms and Skittles don’t count.)

• Be aware of the glycemic index of foods and avoid refined carbohydrates.

Exercise Weight control largely comes down to calories in, calories out. Exercise is calories out. However, the benefits of exercise go far beyond weight control and include building muscle, improving aerobic metabolism, increasing endorphins, and increasing adaptive capacity or resiliency.43–45 The effect on resiliency has been firmly established scientifically but is well known to athletes empirically. The following is a summary of thousands of pages of exercise advice:

• Treat exercise as a medication—because it is.

• You wouldn’t skip your medications, so don’t skip exercise.

• Put aerobic exercise sessions on your schedule for 50 minutes (plus stretching—see the next section) at least four to five times per week. Don’t wait until it is convenient to work out, because it never will be.

• Recent work shows that exercise that involves reacting to the environment, making minute adjustments throughout (e.g., riding outdoors vs. on stationary bikes, running outside vs. on a treadmill), increases both athletic and mental adaptive capacity.

• The great news for gardeners is that working in the yard or garden for an hour burns 300 calories as an aerobic workout. Be sure to stretch afterward.

• The more burned out you feel, the harder it is to make exercise a habit, which makes it exponentially more important. When you find yourself thinking, “Seriously, does it really matter?” look in the mirror and say what you would say to your patients: “It matters, so get started.”

Stretching High-performance athletes use stretching both before and after competition, and healthcare team members should too. Tom Brady has won six Super Bowls and was the MVP of four of them. He is still playing in the NFL at the age of 43. How has he maintained his high performance level so consistently and for so long? Over the course of a three-hour conversation, he summarized his approach:

Doc, most of the strength and conditioning coaches in the NFL focus on lifting weights in various ways, all of which have the effect of building strength, but which also “tighten and shorten” the muscle fibers. That’s not what a quarterback needs to do his job. I do the workouts I am told at the team facility, but then I go straight to my own facility with my own coach (Alex Guerrero), where we spend hours “lengthening and loosening” those same muscle groups, focusing on stretching and flexibility of the tissues. There are a lot of reasons I have been blessed with such a long career, but stretching is among the most important.46

Much of the work we do is physically demanding. Many nurses and physicians walk four to five miles per day on hard floors.47 Surgeons and scrub nurses toil over the operating table for hours. Physicians and nurses in the ICU and offices are constantly moving from patient to patient and task to task. Unsurprisingly, this leads to a higher incidence of back pain in healthcare workers. Indeed, the work seems designed to produce lower back pain.

Much of this can be prevented with simple, brief stretching regimens focused on lengthening and loosening the hamstrings, which are the “silent villains” of lower back pain, since we tend to focus on our backs when they are tight, but hamstrings and hip flexors need to be stretched to relieve that pain.

Here are four stretches that can dramatically improve flexibility. I strongly recommend doing these stretches before, during, and after work, preceded by two to three sets of 6-4-10 breathing.

1. Hamstring and back stretch: Stand with your hips slightly wider apart than shoulder width. Cross your arms in front and gently bend at the waist, lowering your head until you feel a stretch in the hamstrings. Continue to breathe deeply and gradually continue to bend and drop your shoulders. Hold for three 6-4-10 breaths. (Most people feel a “popping” sensation in their back, which is just the discs coming out to a more physiologic length with nitrogen escaping and is nothing to worry about.) Do this before and after work and anytime you feel any element of back pain during work.

2. Hip flexor stretch: The hip flexors control a great deal of our mobility and also contribute to back pain when they are tight. Grab the back of a chair or desk to stabilize, which will engage your core muscles. Fold your right foot over your left knee while standing and gently begin to “sit,” with your right hand applying gentle pressure on your knee. You will feel the gluteal muscles and the other hip flexors stretch. Over time you will be able to get your left knee at nearly a 90-degree angle. Hold for three 6-4-10 breaths. Now repeat with the left side. Do three repetitions on each side.

3. Single-leg glute, hamstring, and calf stretch: From a standing position, stabilize yourself by putting both hands down on a chair or desk. This will activate the core muscles that support your hips, torso, and shoulders. Extend the left leg forward and straighten it, placing your heel on the ground with your toes pointing up. Slightly bend the right leg and push your hips back. Hold this position for three seconds and then stand tall. Do 10 repetitions total, 5 on each side. This stretch should be felt in the glutes, the hamstrings, and the calf of the front leg as well as the triceps and core muscles.

4. Side stretch with rotation: Stand straight in a doorway. Move the left arm up the wall as if you were hanging from a monkey bar. Gently press into the wall with the palm, which will activate the core. Step back with the left leg into a gentle lunge, which will stretch the side and chest muscles. Challenge the position by bringing the left knee closer to the ground. While holding that position, stretch the right arm up and to the right. Lead with the thumb and look at the right hand, while limiting movement in the legs. Hold for three seconds and then return the arm to its starting position. Stand with shoulders back and spine straight. Repeat on both sides for five reps each.

The last two stretches are used with permission from Team Exos and can be viewed here: https://blog.teamexos.com/work-smart/hospital-staff-well-being.

Sleep Sleep plays a major role in intellectual, mental, and physical performance and recovery across all dimensions.48–49 Sleep deprivation increases fatigue, impairs judgment, impedes physical performance, reduces reaction times, increases the risk of injury, and increases patient safety events. Sleep’s effect on fatigue is particularly important—consider the words of Hall of Fame coach Vince Lombardi: “Fatigue makes cowards of us all.”50

Investing in proper sleep length and architecture is one of the best strategies to increase personal resilience or adaptive capacity. Part of resiliency is the ability to “de-form” in order to squeeze through tough circumstances and then “re-form” to get back into action. Recovery and sleep are key to the ability to do this successfully. There are many ways to improve sleep quality, quantity, and architecture, which are briefly summarized here:

• Set a personal goal of getting seven to nine hours of sleep per day.

• If you know when you must get up, work backward from that point to help develop your “sleep ritual” and give yourself at least an hour to prepare for sleep.

• Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone that regulates night and day cycles or sleep-wake cycles. Darkness causes the body to produce melatonin, so sleep in a cool, dark room.

• Light, particularly “blue light” such as light from computers, televisions, smartphones, and some e-readers, decreases melatonin production and signals the body to alertness. Avoid blue light for at least two hours before sleep.

• Exogenous melatonin (5–10 mg), even at the maximum dose, often has a half-life of four to five hours, causing people to wake up before a full seven to nine hours of sleep.

• Sustained-release forms of melatonin are designed to combat this effect.

• The amino acid 5-hydroxytryptophan, either alone or combined with melatonin, can be an effective sleep adjunct.

• More recently, research has shown that phosphatidylserine (100–200 mg at night) increases sleep architecture and duration, as well as increasing focus and attention span.

• For shift workers who rotate day, evening, and night cycles, there are excellent resources to guide effective sleep.

Sunlight For centuries, philosophers and poets have extolled the virtues of sunlight, including its ability to improve mood, attitude, and performance. My grandpa Jim always said, “It’s easier to have an ‘attitude of gratitude’ when the sun is on your face.” Scientific literature supports many positive effects of sunlight, mediated largely but not exclusively through vitamin D3.51–52

All of this must occur with appropriate use of sunscreen to prevent skin cancers and melanoma, of course. But sunshine should be treated as a medication with many positive effects—because it is.

Pursuing Perfection or Pursuing Peace? Engaging the Mind, Body, and Spirit We are all leaders, and we cannot lead effectively without a clearly centered mindset of serving others. That requires finding a way to pursue our own peace. If you want to help others—and all of us do—you must do the work of pursuing not just perfection but peace. Without that core motivation and value, people are unlikely to follow you.

Countless people have informed the literature, art, and science of mindfulness, so to mention some of them risks raising the ire of those who are devotees of others. However, in my admittedly nonexpert study of mindfulness, several names that are most prominent are Michael Singer,4,53 Jonathan Kabat-Zinn,54 Daniel Siegel,55 and from the Buddhist tradition, the Dalai Lama56 and the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh.57 I could not possibly do justice to summarizing their prolific work, but here is my summary of thoughts on mindfulness.

At its core, mindfulness is a self-regulated focus of attention on the present moment, infused with curiosity, openness, acceptance, and surrender, but devoid of judgment, bias, and prejudice. For me, the core of mindfulness is getting out of your own way.

A central feature of all mindfulness is the concept of having a clear understanding of what we control and what we do not control, since it is a waste of time to invest “strategic optimism” in things beyond our control.

Singer, author of The Untethered Soul4 and The Surrender Experiment,53 explains that we have little or no control over the “Outside World,” despite what we might have learned from traditional teachings. This is in contradistinction to the “Inside World,” over which we have complete control, which includes our minds, our emotions, and our thoughts. This is precisely what Epictetus said:

Of things that exist, some are in our power and some are not in our power. Those that are in our power are opinion, choice, the things we do like, the things we don’t like, and in a word, those things that are of our own doing. Those that are not under our control are our bodies, property, possessions, reputations, positions of authority and in a word, things that are not of our own doing. We must remember that those things are externals and are therefore not our concern. Trying to control or to change what we can’t only results in torment.58

Singer correctly notes that we can choose to live inside a “beautiful, centered space”53 if we can but focus on what we can control to the exclusion of what we cannot control. Let the “outside in”

• only as you want or need, and

• do so at considerable peril if you let it control what it clearly does not.

Admiral James Stockdale, whom I quoted earlier, was a navy fighter pilot whose A-4 Skyhawk was shot down over Hanoi, where he was the senior officer held as a prisoner of war. He said that as soon as his aircraft was hit, he thought, “I am descending into the world of Epictetus.”59 In battling burnout, never lose track of what you control—and what you don’t. As Singer says, “The world can be a dangerous place... or a great gift.”4, 53 Balancing that choice goes to the heart of battling burnout.

Both Kabat-Zinn and Siegel have used fMRI to study the effect of mindfulness training and meditation on increasing the signal and capacity of the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain that governs resiliency.54–55,60 The following are the elements that Kabat-Zinn lists as the components of mindfulness:54

• beginner’s mind

• nonjudging

• acceptance

• letting go

• trust

• patience

• nonstriving

• gratitude

• generosity

Call it what you will—mindfulness, reflection, focusing on what matters, source of being, place of peace—it can be a source of healing, but only you can determine whether it works for you. I confess that when writing this chapter, I was reviewing a video on mindfulness when my wonderful wife walked in and asked what I was doing. I said, “I am fast-forwarding through a lecture on mindfulness.” So I am hardly one to tell you whether this will work for you. If you are so inclined, I recommend giving it a try.

Namaste Customs can have great power, and some of the most powerful are greetings. The traditional Sanskrit greeting, much used but less understood, is “Namaste.” There are many interpretations of the term, including “The light in me honors the light in you.” But my preferred translation, based on the wisdom of several colleagues who are fluent in Hindi or Sanskrit, is this, “I greet the God within you.”61

I love that, and I think it is the best way to approach the hard work of healthcare. That is what we do every time we see a patient—we greet the God within them.

Duke WISER Web-Based Training The habits of mindfulness and meditation take time and the investment of energy to develop, as worthwhile as that investment is. Partially in response to this, Bryan Sexton and his colleagues at the Duke University Health System developed WISER (Web-based Implementation of the Science to Enhance Resilience). The program is described in more detail in Chapter 14, but WISER comprises 18 tools developed from the science of positive psychology and tested through a National Institutes of Health Research Project Grant that are designed to cultivate the behaviors of resiliency. They are enjoyable to use, are easy to access, have high utility, and have a quickly measurable but sustainable impact. In particular, I find that these tools are helpful: Three Good Things, Random Acts of Kindness, Gratitude Letter, and Awe.

Think, Laugh, Cry NCAA National Championship–winning men’s basketball coach Jim Valvano gave one of the greatest speeches I have ever heard in accepting the Arthur Ashe Courage Award at the ESPN ESPY Awards. His body riddled with stage 4 bone cancer, he urged the audience to do three things each day: take the time to think, to laugh, and to be moved to tears. As he said, “If you do that, that’s a full day.”

Healthcare team members have the chance to experience things that make us think, laugh, and cry every day. But you must take the time to pause, reflect, and do those things.

Have a Multitasking Strategy

Effective executives do first things first and they do them one at a time.

PETER DRUCKER, THE EFFECTIVE EXECUTIVE62

While Drucker’s advice came well before the “onslaught of electrons” in which our current lives are conducted, it is nonetheless sound counsel to avoid multitasking. While multitasking seems like an unavoidable occupational hazard in healthcare and many people take pride in their ability to multitask, the literature is quite unequivocal that multitasking makes you stupid.63–64 The rates of errors, miscommunication, patient safety incidents, and even malpractice claims rise as the rates of multitasking and interruptions rise.

Follow these two principles:

1. Do everything possible to eliminate multitasking from your work.

2. Develop strategies and tactics to deal with multitasking.

Figure 8-5: Increasing Rewards and Recognition Solutions

GIVING AND GETTING REWARDS AND RECOGNITION

If there is the feeling that team members aren’t appropriately given rewards and recognition for the hard work done, if there is a mismatch between appreciation earned and appreciation received, the best way to fix that is to give rewards and recognition to others (Figure 8-5). While it also ties into values, a culture imbued with praise for others has an infectious effect on the entire team. Indeed, it also affects the patients, who invariably notice people who are gracious and kind toward others.

Take a minute to pause and reflect on the many great things that are done on behalf of patients by you and your immediate team members in just one day. Do the members on your team consistently thank each other for this great work? We need to build “thank-you pauses” into each day to ensure we are increasing rewards and recognition. Of course, we want to increase the amount and quality of the great work done, but why not increase praise for the work already being done?

Reward Yourself: The Power of One The first step in ensuring rewards and recognition is rewarding and recognizing ourselves. Many people live lives where they aren’t ever sure whether they make a difference. That’s not true for the healthcare team, demonstrating what I describe as “the power of one.” When we go into a patient’s room, we can confidently say, “We will make a difference. What will the difference be?” One doctor, one nurse, one team taking care of one patient—we will make a difference; of that there is no question. Rewarding ourselves by recognizing the control we have over our interactions with our patients and families is a powerful way to prevent and combat burnout.

Say “Thank You” 50 Times a Day Since rewards and recognition are contagious, one of the most obvious solutions is to ensure that routinely thanking others is a part of the work life, preferably in a disciplined, thoughtful way. If saying thank you 50 times a day seems a daunting task, consider this:

• Most physicians see at least 20 patients a day.

• Most nurses see at least 10 patients a day.

• The nurses spend more with the patient and the family.

• If each physician thanks the patient when they first see them, thanks them again when they leave, and thanks the nurse for their care, that is at least 60 times a day.

CASE STUDY

In my job as medical director for all 2,500 NFL players, I make a point to attend several training camps each year, meeting with players, coaches, athletic trainers, and the medical staff. When visiting the Denver Broncos several years ago, I was touring the training room with their venerated head athletic trainer, Steve “Greek” Antinopolis. I noticed that every door into or out of the training room has this sign above it: “You can easily judge the character of a man by how he treats those who can do nothing for him.” I asked Greek about it and he said, “Oh, Coach Kubes [Gary Kubiak] feels very strongly that we’re all a part of the team and he stresses this quote to the players constantly.”

When I saw Coach Kubiak several hours later, I complimented him on it and asked where he first heard it. He said his dad told it to him every day. (As some of you know, that quote is from the German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Goethe’s wisdom lives on in an NFL locker room.)

• If the nurse thanks the patient and the family when they arrive and when they leave and thanks the doctor and essential services team, they are past 60 times as well.

• And of course, the more “thank you” is said, the easier and more natural it becomes.

• “Thank you” provides the lubrication to treat “rustout.”

Thank the “Least Important” Team Members We would all do well if that wisdom lived in the halls of our hospitals and healthcare organizations. Do you live by that wisdom?

All the members of our team should be thanked, not just the nurses and doctors, but the technicians, registrars, and environmental services (EVS) folks as well. Making sure to say thank you to all of them every chance you get is a sound investment in preventing and treating burnout. After a difficult trauma resuscitation, it’s not uncommon for the nurses and doctors to thank each other for handling the patient well. But thanking the EVS folks who clean up the mess made during the resuscitation is also a discipline that should be developed. That reward and recognition is well deserved—and always noticed.

Catch People Doing Things Right So much of healthcare is based on a disease model that we often find ourselves focusing on what’s wrong or what went wrong, instead of proactively focusing on what went right and should be celebrated. Unexpected rewards and recognition arise from “catching” people doing things right and publicly complimenting them on their work. No one is immune to the power of praise.

CASE STUDY

The chief nurse executive (CNE) is completing patient care rounding and is hurrying back to her office for a solid day of meetings and phone calls. As she looks back, she sees a wheelchair in the middle of the hallway unattended. As she begins to walk back, a busy nurse comes from a patient room, walks out of her way to get the wheelchair, wipes it with disinfectant, and puts it back where it belongs, never noticing that the CNE is there. The CNE approaches the nurse and says, “I just saw what you did. That was very impressive.” The nurse smiles and answers, “Hey, you’re just visiting, this is where I live—got to keep things squared away.” Before starting her meetings, the CNE takes a moment to send a congratulatory email to the nurse director of the unit, praising the nurse by name. She also writes a personal note to the nurse saying, in part, “You reminded me of why I became a nurse.”

Reconnecting Passion: Great Place to Work = Great People to Work With Reconnecting passion to the job requires a recognition that great places to work arise from the great people who do the work. There is nothing abstract about a great work environment—it is great people with great leaders doing great work in service to their patients. The more this is articulated in what is said and done, the more the team will reconnect their passion and feel appreciated. “You did a great job on that case. Well done!” is a powerful reward and recognition. Writing a letter or email commending the team and copying those in “the C-suite” is also effective, as mentioned in the preceding case study.

Recruiting members to the team is one of the most important investments of time and energy, since it increases the talent pool. Make sure “hire right” includes hiring for passion and an “attitude of gratitude” for the rest of the team.

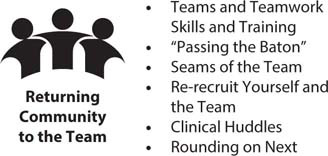

RETURNING COMMUNITY TO THE WORKPLACE

Teams are a community of caregivers who trust each other, and it is critical to accentuate and nourish that sense of community (Figure 8-6). Healthcare is by nature a team effort, but the language and the behaviors used should reflect a community commitment, since all healthcare is “cocreated” by the entire team.

Figure 8-6: Solutions to Return Community to the Team

If you want people to “say team,” make sure you “play” team.

Use the words team and teams regularly, as in “nursing team,” “EVS team,” “nutrition team,” and so on. I accepts responsibility if something goes wrong. We says team when creating expectations or sharing praise.

Re-recruit Yourself and the A-team A great deal of time, effort, and energy goes into recruiting, training, and orienting physicians, nurses, and the other members of the team. Far too little time, effort, and energy go into the process of “re-recruitment,” in which the members of the team or community are continuously reminded of how valued their contributions have been and how critical they are to the success of the team.65 In addition to changing the character of performance evaluations to consider how the work itself can be changed to make their lives easier, letting the A-team members know how much their efforts mean to the patients and the team itself is an important part of re-recruitment daily.

If you don’t “re-recruit” your A-team, someone else will.

Far too few people are aware of this concept of re-recruiting your star performers.

“Huddle Up”: Using Clinical Huddles to Reinforce Community Clinical huddles create teamwork in healthcare, sharing mental models and delineating specific contributions that will be made by team members for the good of the patient. They also ensure that the entire team interacts and prevent people from working in relative isolation through the course of the day. And they create common understandings among the team members, further reinforcing community.

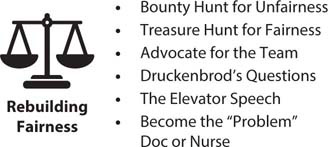

REESTABLISHING FAIRNESS IN AN UNFAIR ENVIRONMENT

As much as values are critically important to preventing burnout, the domain of fairness is where burnout in hospitals is often first noticed. Because of the deeply egalitarian nature of healthcare, it is not surprising that this is the case. However, focusing on fairness also has tremendous leverage on reestablishing the team’s and leadership’s commitment to fairness, equity, and parity, both for the team and for its patients (Figure 8-7).

Figure 8-7: Solutions to Rebuild Fairness

Mutual Accountability and the Language of Fairness Eliminating functional silos (first described by Phil Ensor in 1988)66 and ensuring there is mutual accountability across boundaries is a clear way of ensuring fairness, since many people “say ‘team’” but don’t “play ‘team.’” Mutual accountability involves eliminating statements such as, “Well, the physicians’ patient experience scores are great. It’s the nurses’ scores that are pulling us down.” Instead, an approach that focuses on fairness uses language such as, “We are all in this together. Let’s see what worked in raising the physician scores and see if we can apply that in other areas.” Accountability across boundaries is essential to creating transparent fairness.

The language we use also reinforces both community and fairness. Examples include the following:

• “That was an excellent job!”

• “You just saved this guy’s life!”

• “Thanks! You made a B-team day into an A-team one.”

• “What could I have done today to make your job easier?”

• “Anne picked up some very important information that is going to improve your care.”

• “Isaac is our best advanced practice provider. You’re fortunate he’s here.”

The more this language is used—and used across boundaries—the more evident fairness will be.

Druckenbrod’s Questions Glenn Druckenbrod, the medical director of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, stresses the importance of the discipline of using three questions during the “landing” portion of the ED visit:

• “Have we met your expectations?”

• “What questions do you have that I can help with?”

• “How did we do?”67

These questions signal to the patient and the family that we are committed to fairness.

The Elevator Speech A medical director and her nursing director partner are waiting for an elevator to “round on next” on patients admitted from the ED. The elevator door opens to reveal the following people: the CEO, chief medical officer, chief nursing officer, chief operating officer, chief financial officer, and board chair, who are making their own rounds. Inevitably, they will ask, “How is it going today in the ED?”

The directors’ response is their “elevator speech,”65 which is a focused, insightful, succinct message of “the story of the ED.” The physician and nurse should have their elevator speech prepared and they should have discussed it among themselves, since both will be in the role of “chief storyteller” in explaining the complex adaptive system that every ED is. The story should always begin and end with the patient, not the staff, since that is their main focus—and power. Committing the time and effort to coordinate an elevator speech focusing on the patient helps create a sense of fairness to those who hear it.

Become the “Problem” Doctor or Nurse This solution seems counterintuitive. However, it is wise to develop a reputation for being proficient at solving problems. Because the ED is a complex, adaptive system, problems are a part of its operations. Emergency nurses and physicians solve problems all day, every day, so it is a skill set that is very familiar to them. Being known as a problem-solver of the highest skill is an effective pathway toward building community, both within the ED and throughout the hospital.

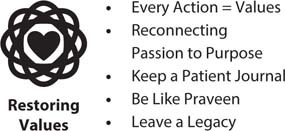

REINFUSING VALUES INTO YOUR PRACTICE

The role of having honorable values in healthcare cannot be overstated, since the work is too hard without a clear connection to our core values of dedication to our patients and to our team members. Figure 8-8 lists ways of doing this.

State Common Values While healthcare teams typically feel they have a set of values to which they hold themselves accountable, it is far less common for people to formally express what those values are. It is even less frequent that they commit those values to writing. Some go as far as to write their own personal vision statement. If we can’t say clearly and succinctly what our values are, how will we or others know them? Stephen Covey wrote eloquently of the importance of this.68

Once you complete a personal vision statement, compare those values with the stated values of the hospital. Are the two sets of values consistent? If not, how do they differ? If the differences between your personal values and those of the hospital differ substantially, how will you reconcile them in your work? Does the experience at work lead them to believe that the actual values of the workplace are different from those proclaimed? After all, “the words on the walls aren’t nearly as important as the happenings in the halls.” Reflect on how they or the practice could change to better reflect the values to which the individual and their colleagues aspire. Until values are understood and articulated, it is difficult to embody them in action.

Figure 8-8: Solutions to Restore Values

Keep a Patient Journal It is a natural human tendency, perhaps accentuated in professionals, to focus on the negative in hopes of finding ways to improve. But physicians and nurses aren’t always great at recalling and reflecting on the good things they do during a normal day. This includes not just saving lives or making a complicated diagnosis but also the simple kindnesses we express to our patients and to each other. One way to ensure that these critically important moments are not forgotten is to write them down. Keep a journal in which you write a brief note—preferably at the end of each shift, but no less than weekly—recalling a patient and their family, or a nurse who made a great pickup, or a doc who was especially kind to others, or a technician who was mentored.

Remember that none of the works of the Stoic philosophers were written as books—most were journals. The most famous such philosopher is Marcus Aurelius, whose only work is Meditations, a collection of the journals he kept for himself—a compelling and lasting piece of literature.69

Don’t be hesitant to praise yourself in thoughts and journal entries. Give yourself credit for what you do well—you deserve it! And don’t be surprised if keeping this journal helps you adopt even more habits of kindness and gratitude.

Be Like Praveen Everyone has heroes in their work whose values inspire us to do better, care more, and care more often. One of mine is Praveen Kache, with whom I worked at Sentara Northern Virginia Medical Center. Praveen is one of the kindest people I know, but this story is about much more than kindness. He was working an overnight shift and an 85-year-old lady was brought in from Brightview, the nearby nursing home and assisted-living facility. She was mentally sharp and had a French accent, having lived in Normandy during the Nazi occupation in World War II. Praveen asked her, “What’s the most important thing I can do for you to make this a great ED visit?” She replied, “Just get me well enough to go back to Brightview.”

Praveen took great care of her, hydrating her and getting appropriate diagnostic tests. He also took the time to sit and talk with her, letting her tell her story. True to his word, he got her back to the nursing home, as she wanted. But one week later, I received a note from the woman (with the beautifully flowing penmanship that is no longer taught) expressing her delight with “Dr. Kache Praveen” (she reversed his name), who “couldn’t have been kinder and got me back to the nursing home, as I asked.” Enclosed was a check for $10,000 made out to the ED. To be honest, for a moment I saw that amount and thought, “That’s a lot of money for someone living in a nursing home. Plus, she’s 85 years old, maybe she mistakenly got the number of zeros confused when she wrote the check.” Well, not only did the check clear the bank, when I spoke to her she said, “I only wish I could have given more.”

We recognized Praveen at the annual medical staff meeting as an exemplary physician and commented on his taking the time to sit and talk with an old lady. He said, “Oh it was my privilege! I treat these folks like they are time machines. When I talk with them, I get to go back in time and experience what they lived through.” He felt it was a privilege on that busy night to go back in time and learn what it was like in Normandy during the Nazi occupation and the liberation in 1944.

Be like Praveen.

Leave a Legacy Some people have jobs that make them wonder, “Do I really make a difference in what I do?” In healthcare, we don’t have that problem—we know we will make a difference in peoples’ lives by using “the power of one.” But what will our legacy be? One of the most wonderful things about healthcare is that we can measure our legacy very easily—one patient at a time. Every time we have contact with a patient—no matter what we do in healthcare—we leave a legacy. Every time we interact with our team members, as we “pass the baton,” we leave a legacy. Even to the people who see us doing our work, we leave a legacy. What an honor to have work that leaves a legacy.

Next time you finish work and get in your car to go home, pause for a moment before starting the engine and ask yourself, “What kind of legacy did I leave in there today?” Very few things are more effective at restoring values in work than considering the legacy you leave.

Summary

• Every healthcare team member is a leader and needs personal resiliency to lead. Every team member is a high-performance athlete who needs training and recovery.

• You are the CEO of “Me, Inc.”—invest in yourself.

• The “big six” are the solutions to reignite passion and personal resiliency that cut across all six of the Maslach domains:

◦ Deep joy, deep needs: Discover where your deep joy intersects the world’s deep needs.

◦ Throw guilt in the trunk—lighten up on yourself: “We have to find a cleaner-burning fuel than guilt.”

◦ Make the patient part of the team: Shift from “What’s the matter with you?” to “What matters to you?”

◦ Personalized patient care: “What’s the most important thing we can do to make this a great experience?”

◦ Chief storyteller, chief sensemaker: Tell the patient the story of their care and make sense of it.

◦ Strategic optimism: Invest your optimism to maximize the ROI.