18

Tools for Changing Culture

As I have mentioned, culture is not just what we do but also what we say we do and how we think about the work and ourselves. We have to be careful that the “words on the walls” match the “happenings in the walls,” or there will be a cultural disconnect. There are six tools to make sure they are aligned.

Tool 1: The Mutual Accountability Jumbotron

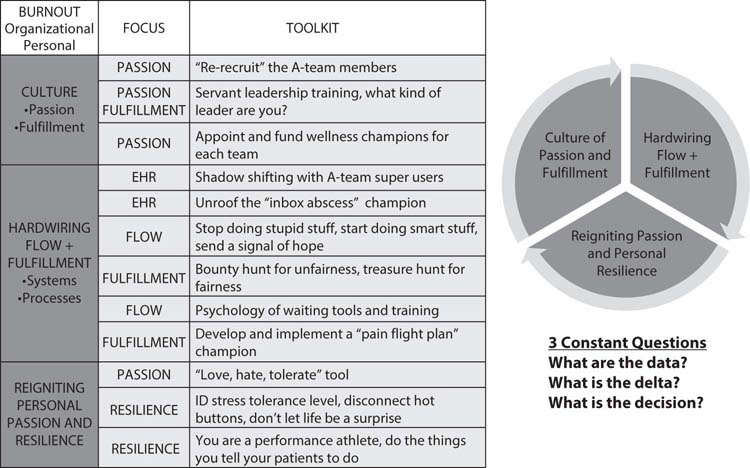

In Chapter 2, I stressed the importance of having a consensus-developed, evidence-based, metrics-supported, and transparent means of communicating the strategies and tools that will be used to battle healthcare burnout. The Mutual Accountability Jumbotron is the clearest way I have found to do so. It serves two important functions. First, it is a simple, clear graphic that shows the efforts that the team is undertaking and how each relates to all other efforts. Second, it allows a visual representation of mutual accountability for each of the team-developed strategies to increase fulfillment and attack burnout. It is an overall game plan the team generates and follows, even while adapting to iterative changes. Figure 18-1 shows the context in which it should be developed, including the “three constant questions” regarding “data, delta, and decision.”

The jumbotron is the single most important tool because it puts the change effort in perspective for the entire team, giving them the chance to “see the entire field,” as we say in the NFL. It provides a pathway to the vision required to see how the efforts interrelate across culture, the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment, and personal passion and resiliency, as well as allowing updates to show progress. For those involved in collaborative, consortium, or benchmarking work, it also shows comparisons with the work from other organizations.

Tool 2: The A-Team/B-Team

One of the best ways of making the job easier can be demonstrated with this tool, which, like others in the toolkit, uses the Socratic method of posing questions to the team, whose answers illuminate knowledge they already implicitly had but had not explicitly expressed. It taps into fundamental insights regarding intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation and the necessity for personal as well as organizational change and resiliency. It was discussed in Chapter 5. It helps people understand that they were already doing what the change requires—just not consistently.

Figure 18-1: The Mutual Accountability Jumbotron, the Three Core Elements, and the Three Constant Questions

1. To set the stage, let them know this is an interactive exercise, the success of which depends on their honesty and willingness to participate.

2. Start by saying, “Let’s talk a little bit about the teams with which we work, as well as what works for us and what doesn’t work.”

3. Pose this question: “Are there days when you go to work and you look around at the people you will be working with and say, ‘Bring it on. This team is going to make things happen, no matter how busy it is’?”

4. When people nod their heads, ask them, “What do you call that ‘can do’ team?” They will all say, “The A-team.”1

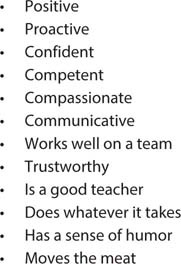

5. Then ask them, “What are the attributes or attitudes of the A-team?”

6. Capture the team’s responses and build on them, possibly using a flip chart. Then ask, “These are the attributes you love, correct?”

7. Show them Figure 18-2 and discuss it briefly, linking to the “why” of making the job easier.

Figure 18-2: The Attributes and Attitudes of the A-Team Members

Figure 18-3: The Attributes and Attitudes of the B-Team Members

8. Now ask them, “Are there also days when you come to work, see the people you will be working with, and think, ‘Shoot me, shoot me, shoot me. I can’t work with you—I worked with you yesterday. Who makes the schedule around here?”

9. After the laughter dies down, ask, “What do you call that team?”

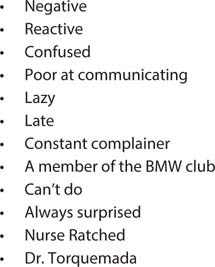

10. After they say, “The B-team,” ask them what the attributes and attitudes of the B-team members are. Briefly discuss and record them, then show them Figure 18-3, taking the time to read through the items listed.

11. When you come to “Nurse Ratched” and “Dr. Torquemada” (reminding them that Tomas Torquemada was the grand inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition), ask, “Do you know who the Nurse Ratched and Dr. Torquemada are on your team?” After they say yes, make the point that everyone knows who Nurse Ratched and Dr. Torquemada are, except Nurse Ratched and Dr. Torquemada.

12. This helps make the point that the B-team members usually don’t realize that they are B-team members, whose behavior is toxic to the people with whom they work.

13. For that reason, as leaders, we have to “hold the mirror up to them” to show them what their behaviors are doing to the team.

14. Finally, ask, “How many B-team members does it take to destroy an entire shift?” Be ready for them to literally shout the answer, “Just one.”

15. This last piece is the wisdom they had all along, which is that B-team members and their behaviors are a major source of burnout among us all. (I like to say that B-team members are like “space-occupying lesions,” since they are not neutral but in fact drain the energy of the team dramatically.)

Tool 3: Leading from the Front

The job is always easier when the leader is visible “on the front lines,” particularly during times of change. Showing the way is an essential skill of all leaders at all levels.

1. Frame the discussion with the importance of leadership and the need to lead oneself and lead one’s team.

2. Alexander the Great’s wisdom is helpful: “An army of sheep who are led by a lion will always defeat an army of lions who are led by a sheep.”

3. Discuss how all great leaders lead from the front, exposing themselves to the same dangers and threats as those they lead.

4. Use this background to pose several questions:

– Who is the leader you have most admired in your career?

– Why?

– Did he or she lead from the front? Give an example.

– Think of a leader who was not as effective. Why?

– Did he or she lead from the rear?

– How will you lead from the front next time?

Tool 4: What Kind of Leader Are You?

All team members are leaders, of themselves, their team, and their healthcare system. Every job is easier when leaders have a clear vision of their passion, as well as a mental model of what type of leader they aspire to be. Leading with purpose requires sufficient thought about the kind of leader you aspire to be. The type of leader you aspire to be will significantly shape your culture and that of the organization.

1. Frame the discussion by stressing the importance of leadership at all levels, from personal to organizational.

2. Discuss how great leaders have different styles and are influenced by many different ways of thinking.

3. Present team members with the following prompt: “Fill in the blank: ‘I am a _____ leader.’” Here are some examples:

– servant leader

– influence leader

– stoic leader

– mindful leader

– Zen leader (which has a certain paradoxical quality)

– power leader

– authoritarian leader

– transformational leader

4. “What experiences or beliefs made you choose that particular word?”

5. “Did you have a mentor who was that type of leader?”

6. “If so, why were they a mentor to you?”

7. “If you can think of an example, please share it.”

8. “If you have that mental model of leadership, what could you do to build those skills? What types of behavior would make you more of that type of leader?”

Tool 5: Trust—Leadership’s Essential Tool

Trust is one of the most important and treasured facets of leadership. Without trust, there can be no teamwork, no courage to innovate, and no “glue” to hold the team together. Once trust is earned and cultivated, it makes all aspects of the job easier and thus provides a critical “why.”

1. Frame the discussion simply:

– A team is not a group of people who work together.

– A team is a group of people who trust each other.

2. Leading ourselves and leading our teams require trust.

3. Trust takes time to build, but only a few seconds to destroy.

4. Pose these questions:

– Whom do you trust?

– Why?

– How long did it take for that trust to develop?

– Whom don’t you trust?

– Why?

– Was there a time that trust was present and lost?

– Why?

– How can we build trust in our team?

Tool 6: The Shadow-Shifting Tool

Change is difficult and requires changing old and often deeply ingrained habits. Part of the frustration arises from the “myths of impossibility and autonomy.”2 The myth of impossibility is, “It can’t be done here—my patients are different.” The myth of autonomy is, “That’s not how I do things.” Both are major obstacles to change and therefore progress.

Shadow-shifting is an excellent tool to break through these myths and make progress not just in metrics but also in making the job easier—the primary “why” of intrinsic motivation.

1. Frame the discussion by defining “shadow-shifting,” which simply means that team members who have consistently attained metrics or a reputation for A-team behaviors and talents will share their experience with those who are struggling by rounding with them as a coach.

2. It is helpful to address the myths of impossibility and autonomy in this way:

– “I appreciate your belief that ‘it can’t be done here,’ but the fact is that it is being done here by others, which is supported by their scores. Perhaps it isn’t being done consistently enough by all team members.”

– “We are a team, and great teams have coaches, who share the experience of their journey to excellence.”

– “As a team, we want to invest in you by giving you the best coaching your teammates can provide in a collegial, professional fashion. That’s what shadow-shifting is all about.”

– “As to the myth of autonomy, we are a team, and teams share positive tools and techniques with each other. If your behavior is producing superior results, have the courage to share it. If not, have the courage to accept coaching and mentoring from your team.”

3. In almost every instance, shadow-shifting is a change in culture and should be recognized as such.

– B-team members will resist coaching. Respond by saying, “Staying the same isn’t an option. We’re offering help. Do you want that help?”

– A-team members often resist coaching by saying, “Who am I to tell others what to do?” Respond by saying, “You’ve demonstrated sustained excellence. Don’t you want to help your teammates, particularly those who are struggling?”

4. A-team members should round with B-team members. Here is a suggested format:

– Two to four hours is plenty of time to get the necessary observational work done.

– A-team members should observe, avoid interruptions, and generally take mental notes of what they see and how it compares with their habits.

– Use evidence-based language to introduce yourself and your teammate to the patient: “I’m Dr. Mayer, and this is Dr. Schmitz, who is working with me today. You get two doctors at no extra charge. We will be comparing ideas to give you the best possible care.”3

5. Broadly speaking, there are three formats to follow, but my experience is that the third works most effectively. If possible, allow the mentee to choose which format to use.

– The coach can make comments after each patient encounter, giving gentle advice and suggestions each time. This has the advantage of giving immediate feedback and not having to recall previous patient encounters (which can be addressed by taking notes), but can have the disadvantage that the person being coached may feel he or she is constantly being criticized, no matter how gentle the coaching.

– The coach can wait until the end of the shadow shift to summarize all the comments, which keeps from interrupting work flow, but can make the mentee feel as if he or she is “drinking from a fire hose” with all the coaching comments.

– The coach and the mentee can pull up after either a certain number of patients or a specific period of time to share ideas.

6. Here are some suggestions for how the coaching can occur during shadow-shifting, always starting with the positives, and then moving to areas for improvement:

– “First, you are clearly a very warm and caring physician, which all of us recognize. I noticed that you make a point to sit down when you talk to the patient, which works very well for me, too. Your clinical knowledge is without equal, as we all know.”

– “I noticed that you make a point of nodding your head and saying yes, which is something I want to develop as a habit. I like that.”

– “I noticed that when you don’t sit, you have a tendency to cross your arms, which produces body language that says, unintentionally, ‘I’m closed to your message.’ I’ve found that using open body language is very effective for me.”

– “I’m sure you don’t realize it, but you have a tendency to interrupt the patient before they have had a chance to fully answer your question. It’s always a rush around here, but I had to fight to make sure I let the patient give a full answer.”

– “One of the things I’ve found helpful is to use active listening with the patient when I explain the treatment plan, testing, or discharge plan with the patient.”

– “I noticed that several times you said, ‘I’ll take great care of you.’ That’s wonderful, but someone suggested using ‘we’ instead of ‘I.’ It helped me a lot. You might consider that.”