11

Overview of Training and Development

CHAPTER OUTLINE

• Education-Training Dichotomy

• Informal and Incidental Learning

Instructional Systems Development (ISD)

Training for Performance System (TPS)

• Structured on-the-Job Training

Introduction

Training and Development (T&D) makes up the primary realm of HRD activity. T&D is defined as a process of systematically developing work-related knowledge and expertise to improve performance. Training is not education-light—it is more than knowledge. People experiencing T&D should end up with new knowledge and do things well after they complete a training program (Zemke, 1990). New knowledge by itself generally is not enough.

Within T&D, more effort is focused on training rather than development. Also, training is more likely focused on new employees and those entering new job roles in contrast to long-term development. The development portion of training and development is seen as “the planned growth and expansion of knowledge and expertise of people beyond the present job requirements” (Swanson, 2002, 6). In most instances, development opportunities are provided to people who have a strong potential to contribute to the organization. Indeed, development often comes under the banner of management development, leadership development, and career development. In every case, people at all levels in all organizations need to know how to do their work (expertise) and generally need help with their learning. Davis and Davis (1998) provide an explanation that helps to frame this chapter:

Training is the process through which skills are developed, information is provided, and attributes are nurtured, in order to help individuals who work in organizations to become more effective and efficient in their work. Training helps the organization to fulfill its purposes and goals, while contributing to the overall development of workers. Training is necessary to help workers qualify for a job, do the job, or advance, but it is also essential for enhancing and transforming the job, so that the job actually adds value to the enterprise. Training facilitates learning, but learning is not only a formal activity designed and encouraged by specially prepared trainers to generate specific performance improvements. Learning is also a more universal activity, designed to increase capability and capacity and is facilitated formally and informally by many types of people at different levels of the organization. Training should always hold forth the promise of maximizing learning. (44)

T&D, as defined here, often appears under other names. Organizations will usually title T&D functions to match their communication goals. Beyond T&D, some carry broader names such as executive development or corporate university. Others are very specific, such as flight safety school or sales training department. Whatever the title, it is good to look beyond the name to see what is taking place. The “university” title might be teaching participants how to flip hamburgers.

Views of T&D

Fortunately, no single view of T&D exists. There is so much variety in the nature of organizations, the people who work in them, the conditions surrounding the need for human expertise, and the process of learning that a single lens would be inadequate. Alternative views are helpful. Three models that help in understanding T&D include the education-training dichotomy, the taxonomy for performance (Swanson, 2007a), and the informal and incidental learning model (Marsick and Watkins, 1997).

EDUCATION-TRAINING DICHOTOMY

The role of general knowledge versus specific job-related knowledge and expertise is an ongoing issue within organizational systems that sponsor T&D (Buckley and Caple, 2007). General knowledge that an individual has is marketable throughout the job market. For example, the ability to read, write, and do math is not specific to any one organization. Thus, employers generally do not want to pay for programs that do not directly benefit them. Most organizations view high school programs and many college degree programs as providing the required general knowledge. They hire graduates of these educational programs with the understanding that the new employees will need to learn the specific job knowledge and skills required by the employing organization.

Companies resist paying the bill for general knowledge learning programs, and governments resist paying the bill for organization-specific learning programs. Having said this, it is even messier in practice. Companies requiring entry-level workers in a tight labor market can find themselves providing basic education (reading, writing, etc.) and job-specific training. They will often appeal to government agencies for funding for these efforts or for gaining access to public-sector adult education resources to help them. Conversely, public-sector economic development agencies often proactively fund job-specific T&D programs to maintain or attract new business and industry in their geographic area.

The politics and pressures surrounding human capital development, within and between organizational systems, influence T&D decisions and programming. Questions of survival, competitive advantage, and the pursuit of defined strategies directly influence T&D decisions. For example, employing organizations may decide to support tuition reimbursement for those desiring general learning as long as they go about it on their own time. Tepid organizational support of tuition reimbursement programs may have as much to do with providing competitive employee benefits (holding on to good employees) as it does from expecting any direct performance return on their expenditures.

TAXONOMY OF PERFORMANCE

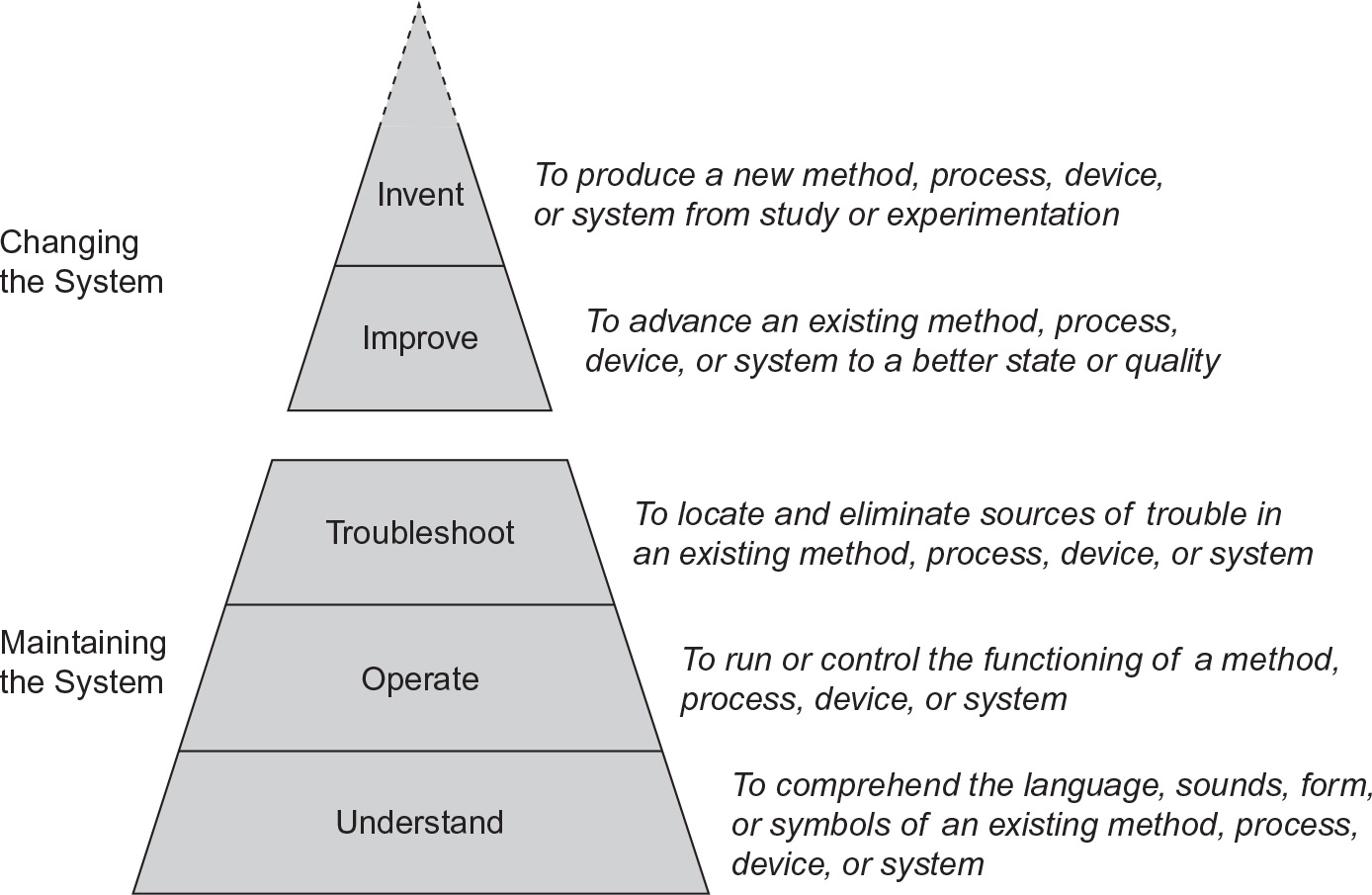

One way of gaining a clearer perspective of the expertise required of organizations is through the taxonomy of performance (Swanson, 2007a; see figure 11.1). The taxonomy first illustrates the two considerable challenges that every organization faces that T&D is expected to address: maintaining the system and changing the system. Keeping any work system up and running is a challenge. Workplace systems erode in many ways. For example, equipment wears out, customers demand more than the work processes can produce, required information is less readily available, and expert workers leave their employment for various reasons.

Figure 11.1: Taxonomy of performance

Source: Swanson, 2007a, 24.

Even though a work system is mature and reasonably predictable, conditions can change quickly, and things can go wrong. A variety of forces cause systems to erode. Thus, managers and workers have the continuing pressure of maintaining their work systems. When there is inadequate expertise, training can be applied. Furthermore, the three “maintaining the system” subcategories of understanding, operation, and troubleshooting of work systems allow for clearer specification of the expertise required and what it takes to achieve it. You could not expect a person trained only to “understand” a work system to then be able to go into the actual workplace with the expertise required to “operate” and “troubleshoot” that system. A fundamental error in HRD practice would be to provide training to employees at a lower level and expect them to demonstrate expertise at a higher level.

It is generally assumed, either through on-the-job experience and formal training, that people who have designed and worked successfully in a system are subject-matter experts on that system. Thus, these subject-matter experts are vital resources for T&D professionals wanting to analyze what a person needs to know and do to maintain the system. In addition, supporting documentation about an existing system is usually available that can also be used to put together sound training.

In contrast to the challenge of maintaining systems, the challenge of changing systems is presented by the taxonomy of performance. Changing the system can mean either improving the system or inventing a whole new approach. Changing the system strikes another chord. What a person needs to know and do to change a system is to engage in activity that is primarily outside the maintaining realm. A person needs expertise in problem identification and problem-solving methods. For example, training in human-factors design, process redesign, and statistical process control are specific strategies for improving the system. Once learned, the person can apply them to an existing work system needing improvement. Interestingly, a person can be an expert in improvement work without being an expert in the system they wish to improve. The T&D professional typically partners with people having system-specific expertise. In other situations, organizations train people on tools to improve the system with the expectation that they can apply those tools to change the system in which they work. Thus, they are expecting the same people to be able to maintain and improve systems. Leading teams that carry out improvement efforts can jump over to the realm of organization development, the natural partner of T&D.

The invention level of changing the system has little regard for the existing system. New ways of thinking and doing work are entertained. One measure of success is that the existing system goes away due to being replaced by the new system. The challenge then is to maintain the new system. This cycle of renewal is fed by HRD interventions and ends up requiring still more HRD interventions. Two examples include T&D experiences in scenario planning (see Chermack and Burt, 2008) and antecedents to creativity (Robinson and Stern, 1997). It is part of the dynamic of the HRD profession that both these demands of maintaining the system and changing the system can go on simultaneously in organizations.

Experts on changing the system (see Brache, 2002; Deming, 1986; Rummler and Brache, 1995) provide us fair warning about maintaining the system and changing the system in organizations. An organization in crisis first needs to focus on the fundamental issue of maintaining the system before changing the system. While improving the system may be more appealing, it would be analogous to rearranging the chairs on the deck of the Titanic. We have started with a “changing the system” project more than once, only to discover a desperate need to develop core workforce expertise to get the system functioning at an acceptable level. Once stabilized, changes to the system could then be entertained.

The more radical invention level in the taxonomy of performance rejects the present system and sets up a clean slate. Steven Jobs (Isaacson, 2011) and Elon Musk (Redding, 2019) are two revolutionary entrepreneurs that group high-energy experts into work/learning teams that identify needs and create solutions—inventing systems.

The learning and performance paradigms discussed in chapters 8 and 9 play important roles in meeting the challenges posed by the taxonomy of performance. With learning viewed as a driver of performance, it is easy to make a short-term connection between learning and performance when there are system maintenance issues. In comparison, it is not as easy to make the long-term learning-to-performance connection when T&D is involved in system change issues. The extended time required to change a work system makes it more difficult to claim system performance gains and suggests that intermediate evidence of learning and new work behaviors are legitimate short-term goals until the change takes full effect.

The traditional lines often drawn between those people working in a system, those responsible for maintaining it, and those responsible for changing the system have been blurred. Some traditional thoughts about hourly workers getting short-term training versus salaried workers earning longer-term development experiences have also been confused. Strategies must be thought through for each setting based on accurate analysis of the expertise required to function in specific jobs.

INFORMAL AND INCIDENTAL LEARNING

While it has been known all along, T&D professionals have recently written about the unstructured dimensions of workplace learning. Most T&D professionals had advocated their structured training view without acknowledging the unstructured, or trial-and-error, role of learning in the organization. The classic rival to structured T&D has been unstructured T&D. Swanson and Sawzin (1975) define each, noting that the difference was whether or not there was a plan for learning coming from the organization: plan denotes structured training, or no plan equals unstructured training. Planning is at the heart of the argument. Jacobs is credited with consciously differentiating on-the-job training as structured or unstructured (see Jacobs and McGriffen, 1987).

The study of unplanned informal and incidental workplace learning has gained interest in recent years. These studies are based on the reality that most of what people learn related to their work performance is not planned in the way T&D professionals have traditionally thought about work-related learning.

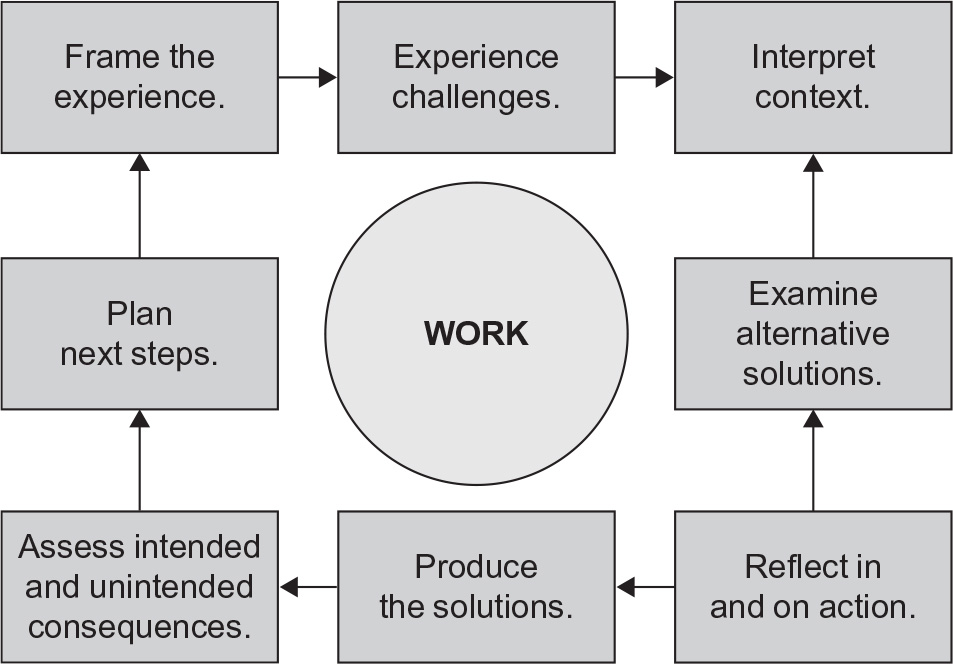

Marsick and Watkins (1997) provide an “informal and incidental learning model” to understand this phenomenon (see figure 11.2). Their model is based on a core premise that the behavior of individuals is a function of their interaction with their environment (Lewin, 1951). Work and the workplace context are at the core of informal and incidental workplace learning (Nijhof and Nieuwenhuis, 2008). One could argue that the moment an organization begins planning and taking actions to encourage informal and incidental learning, the process is no longer informal or incidental. Such an argument would shortchange the confidence in the capability and integrity of workers as learners that the informal and incidental learning perspective offers. They highlight the power of the context—the organization and the work—both to ignite the learning process and serve as the primary learning aid. The work requirements provide the challenge to learn, define problems, and solve problems, but there is usually no time to reflect. In this vein, Nijhof (2006) cautions the profession about the limitations of the learning potential of work settings that demand ongoing performance. The evolution of the internet as a storehouse of information with individuals who have access to computers and smartphones is a game-changer. Individual employees can obtain real-time data and instruction at their command. Caution abounds about being able to discern the integrity of the information appearing on the internet.

Figure 11.2: Informal and Incidental Learning Model

Source: Marsick and Watkins, 1997, 299. Used with permission.

As a middle ground, it is no wonder that organizational leaders are interested in ideas that embrace action learning and team problem solving. Action learning results in learning and possible solutions to real contextual problems. Team problem solving results in solving a specific organization-specific problem with learning as a vehicle or side benefit. Both action learning and team problem solving rely on the power of work and the work context.

Key T&D Terms and Strategies

Key training and development terms and concepts provide a basis for understanding the profession. Expertise, a human state, is acquired through a combination of knowledge and experience. It enables individuals to consistently achieve performance outcomes that meet or exceed the performance requirements (see chapter 11 for a full discussion of expertise). Training is the process of developing knowledge and expertise in people. Development is the planned growth and expansion of the knowledge and expertise of people beyond the current job requirements. This is accomplished through systematic training, learning experiences, work assignments, and assessment efforts.

T&D interventions vary in the amount of their structure. It is typical for T&D programs focused on life and death matters—such as medical surgery, flight operation, nuclear power plant operation, and proprietary financial investment strategies—to be highly structured. This is especially true in managing the experiential portion of the T&D program (beyond knowledge) and verifying the attainment of the required expertise.

T&D can take place on the job or off the job. On-the-job programs take advantage of the resources of the workplace and actual conditions in which the person will be expected to perform. Off-the-job offerings allow learners to disconnect from the pressures of the workplace to entertain new information and better ways of doing things.

Individual T&D program titles are generally derived from job titles, job tasks, work concepts, work systems, work processes, or hardware/software. T&D programs can be custom produced or purchased off the shelf. Custom-produced programs are designed to match the same performance, learning, and expertise requirements of a specific group of people in a specific organization. Off-the-shelf programs are generic, generally cost much less, and are less likely to fully address the organization’s particular learning or performance needs. Organizations sometimes buy off-the-shelf programs from external providers and then customize portions of the program to establish a better fit.

SUBJECT MATTER FOCUS OF T&D

Technical T&D programs are generally thought of as people–thing, people–procedure, or people–process focused. They are often classified and administered under varying banners within the same organization. For example, a large corporation with multiple divisions producing unique products or services can have division-level skill and technical training functions that are focused on the substance of the division-level technology.

In contrast, management and leadership T&D is almost always held constant across an organization. These programs focus on people–people and people–idea expertise that mirrors organizational culture and strategy that transcend specific divisions. Expertise required of managers and supervisors focused on getting the work done—maintaining the system—with a lesser concern for improving and changing the system. In comparison, leadership tasks are more likely focused on concerns about the future state of the system while not losing sight of the present.

Motivational T&D is a smaller segment of programming that focuses on attitudinal content in the forms of values and beliefs. It is generally pursued through intense, structured experiences. Dynamic presentations by role-model facilitators and placing people in unfamiliar settings, such as wilderness or survival situations (that are quite safe), are two familiar strategies. Motivational T&D programs are often used to create readiness for change, followed by either technical or management programs to develop the expertise required to carry out the change.

Career growth T&D is an extended view of the learning and expertise development journey. A simple example would be to plan and construct a purposeful pattern of T&D experiences with an eye toward the long-term development of one’s career. A significant shift in this realm took place in the 1980s. Many firms were sponsoring career development programs that groomed people to move up in their stable organizational system. Once the realization hit that firms were changing rapidly and unpredictably, organizations cut back on their career development programs. Thus, the locus of control for career development moved from the firm to the individual. When a person is asked today, “Who is in charge of your career development?” the answer is most likely—“I am.” Many employees are inadequately prepared to manage their career development and are working in organizations that are tenuous about their futures. Individuals respond by enrolling in public career development seminars or hiring personal coaches. With the amount of organizational disruption, it is common for individuals to skip career tracks and essentially start over or at a lower level than they had previously. In the past, this would have been an enormous negative, while today, it is seen as acceptable.

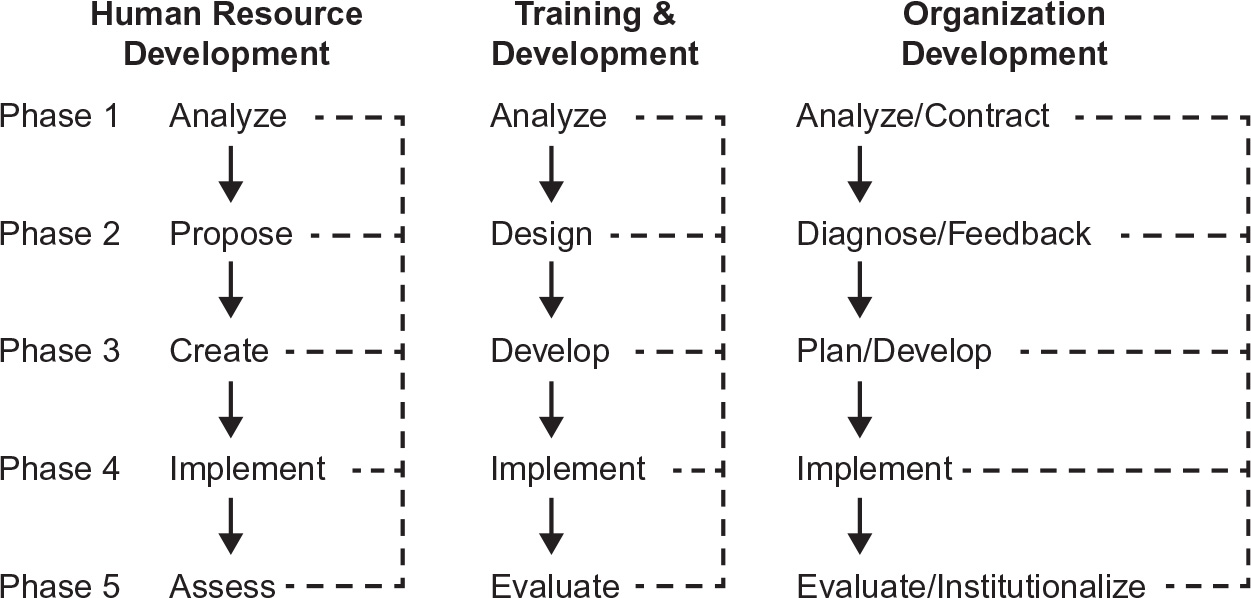

The General T&D Process

HRD is characterized as essentially a problem-defining and problem-solving method. A positive word could be used for those who react negatively to problems (e.g., opportunity, improvement, etc.). HRD, T&D, and OD are all characterized as five-phase processes. Variations in the wording for the HRD, T&D, and OD processes capture the common thread used by professionals. Here are all three variations:

T&D professionals within HRD most commonly talk about their work in terms of the ADDIE process (analyze, design, develop, implement, and evaluate). It is the most widely used methodology for developing systematic training (Allen, 2006). The origin of the ADDIE process is rooted in the early four-step training method and the instructional systems development model. The WWI and WWII training within industry project (Dooley, 1945b) laid out the four-step training method:

1. Prepare the learner.

2. Present instruction.

3. Try out performance.

4. Follow up.

The instructional systems development (ISD) model was developed by the U.S. military in 1969 (United States, 1969; Campbell, 1984). Many contemporary training models are grounded in these early systematic training efforts.

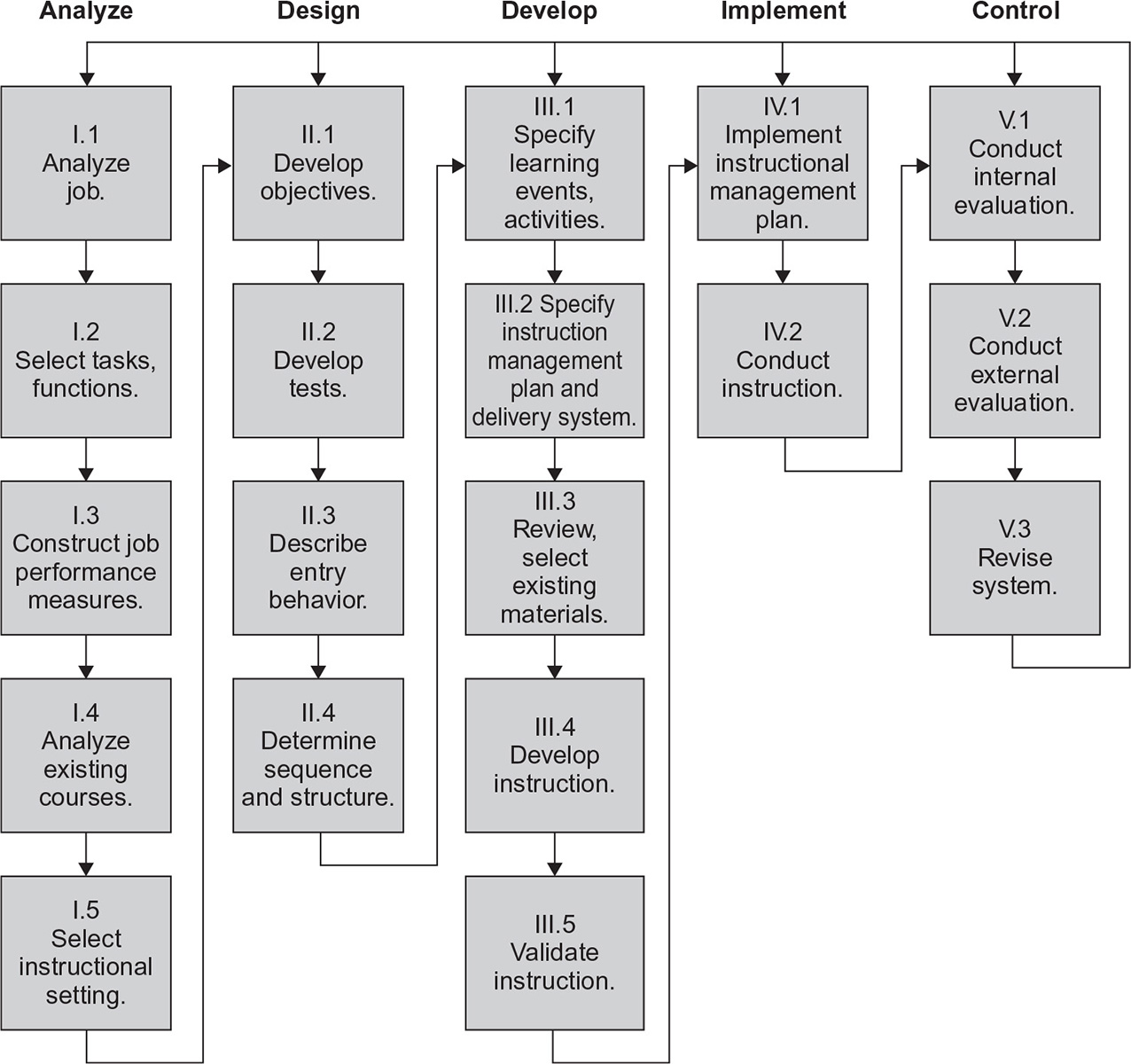

Instructional Systems Development (ISD)

The instructional system development (ISD) model was developed by the United States to go about training systematically and effectively in the context of the enormous military training enterprise. Furthermore, it was meant to provide a common language and process that transcended the various branches of the military service.

The ISD model is illustrated in figure 11.3. The top level shows the five phases of the training process in its original form as analysis, design, develop, implement, and control. The control phase was later changed to evaluation in most adaptations of the original ISD model. Under the phases are numerous steps within each.

In that the original ISD was designed for the military and not for smaller organizations, the ISD is best suited to the following conditions:

• Large numbers of learners must be trained.

• A long lifetime is expected for the program.

• Standard training requirements must be maintained.

• High mastery levels are required because of criticalities, such as safety or the high cost of errors.

• Economic value is placed on the learner’s time.

• Training is valued in the organizational culture (Gagne and Medsker, 1996).

The original IDS model began with the assumption that training is needed. Thus, the beginning point of the analysis phase was to analyze the job and its tasks. The ending points were to assess trainee behaviors and to revise programs as needed. The sheer size of the military and the degree of standardization in personnel and equipment helped shape the original ISD model with features that were incompatible with most business and industry training requirements.

Figure 11.3: The Model of Interservice Procedures for Instructional Systems Development (ISD)

Allen (2006) offers the following reflections on the ADDIE training model:

The ADDIE process is an adaptation of the systems engineering process to problems of workplace training and instruction. The process assumes that alternative solutions to instructional problems will be more or less cost efficient depending on the instructional need and environmental constraints, and that a systems approach intelligently choosing among alternative solutions will produce the most effective results. . . .

In practice beyond the military context, the ADDIE process was found to be too rigid and did not account for the different situations and applications for which it had to be used. To account for the situational differences, the external control of the system (i.e., the boxes and arrows) gave way to phases of ADDIE that could be manipulated in any order by the training professional. This third generation model assumed that ADDIE was an interactive process that could be entered at any point depending on the current situation. Although behavioral learning theory was still dominant, cognitive theory was beginning to have an impact, such as in the use of simulations for acquisition of cognitive expertise in decision-making. (431)

The estimates on the evolution of ADDIE suggest that over one hundred variations of the model exist.

Training for Performance System (TPS)

The training for performance system (TPS) is a process for developing human expertise to improve organization, process, and individual performance.

The TPS was initially developed in 1978 by Richard A. Swanson for a major U.S. manufacturing firm. The firm wanted a comprehensive training process that would embrace training at all levels (corporate, division, and plant; management, technical, and motivational), thus allowing for a common systematic approach and common language for personnel training throughout the company. The TPS can be viewed as a major adaptation of the earlier ADDIE model and more appropriate for dynamic organizations.

When the TPS was developed in the late 1970s, the sponsoring firm raised several issues about the existing state of the training profession. (1) There was a concern about the inadequacy of the dominant ISD model to connect with core business performance requirements at the analysis phase. (2) The firm pointed out the inadequacy of the work analysis tools and processes used in management T&D to get at the substance of knowledge work. (3) The firm was also concerned about the inadequacy of the analysis tools and processes being used in technical T&D in getting to the heart of systems/process work, not just procedural work. (4) There was a concern about the inadequacy of the dominant instructional systems development (ISD) model to connect with core business performance outcomes at the evaluation phase.

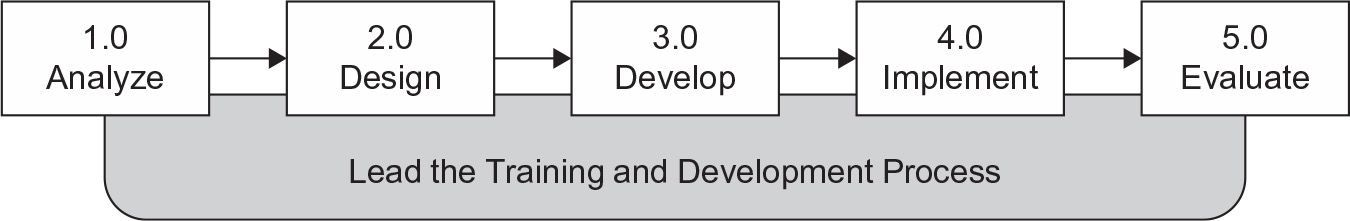

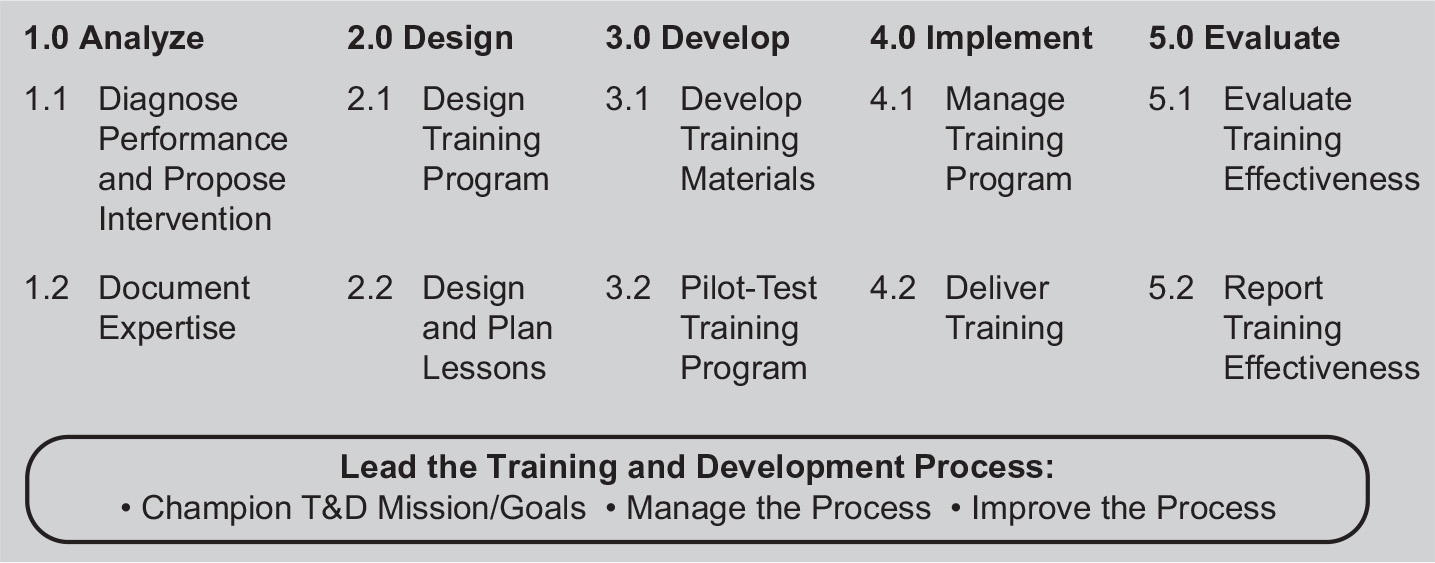

The TPS embraces the titles of the traditional five phases of training presented in most models (Swanson, 1996b; see http://www.richardswanson.com): analyze, design, develop, implement, and evaluate with the addition of the critical overarching phase of “leading the T&D process.”

TPS MODEL

The TPS model is illustrated in two forms in figures 11.4 and 11.5. Figure 11.4 shows the basic five phases of the training process being integrated and supported through leadership. The second graphic of the TPS model, figure 11.5, specifies the major steps within the phases and the leadership component.

The training for performance system (TPS) is a process for developing human expertise for the purpose of improving organizational, process, and individual performance.

Figure 11.4: Training for Performance System

Source: Swanson, 2002.

Figure 11.5: Steps within the Process Phases of the Training for Performance System

It is important to note that the integrity of the TPS systematic process can be maintained even in the simplest of situations (severe time and budget constraints) or can be disregarded in the most luxurious cases (generous time and budget allocations). Professional expertise—training process knowledge and experience—is what is necessary to maintain training integrity.

PHASES OF THE TPS

The TPS is a process for developing human expertise to improve organization, process, team, and individual performance. A closer look at its five phases and the overarching concern for leading the process are below:

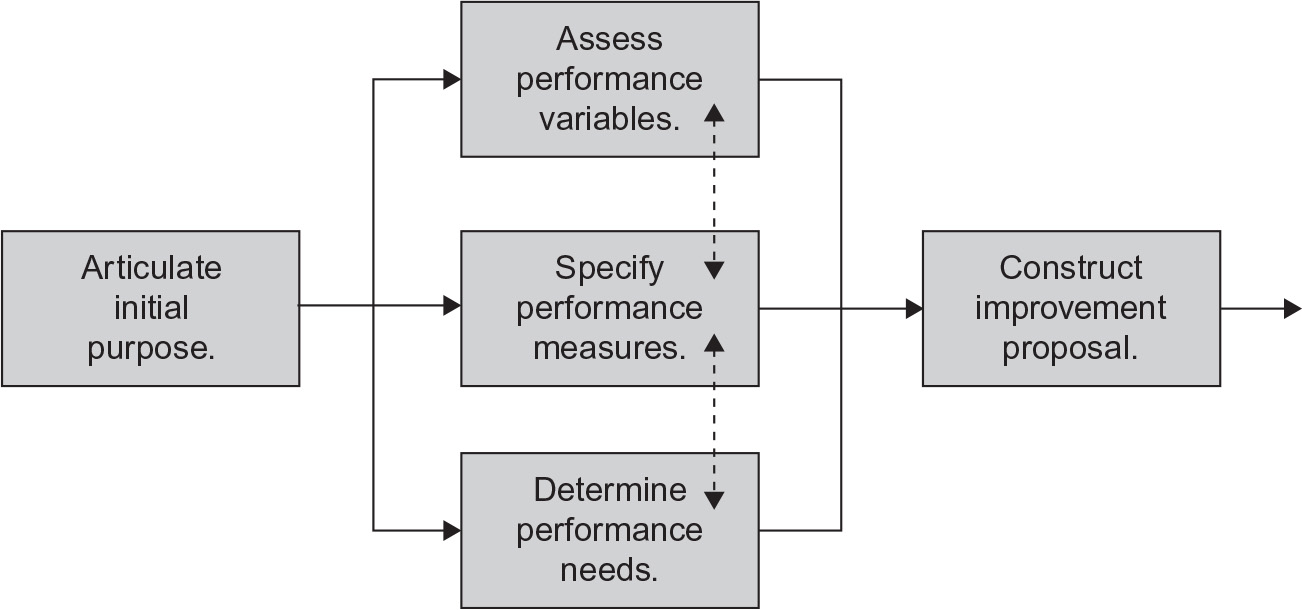

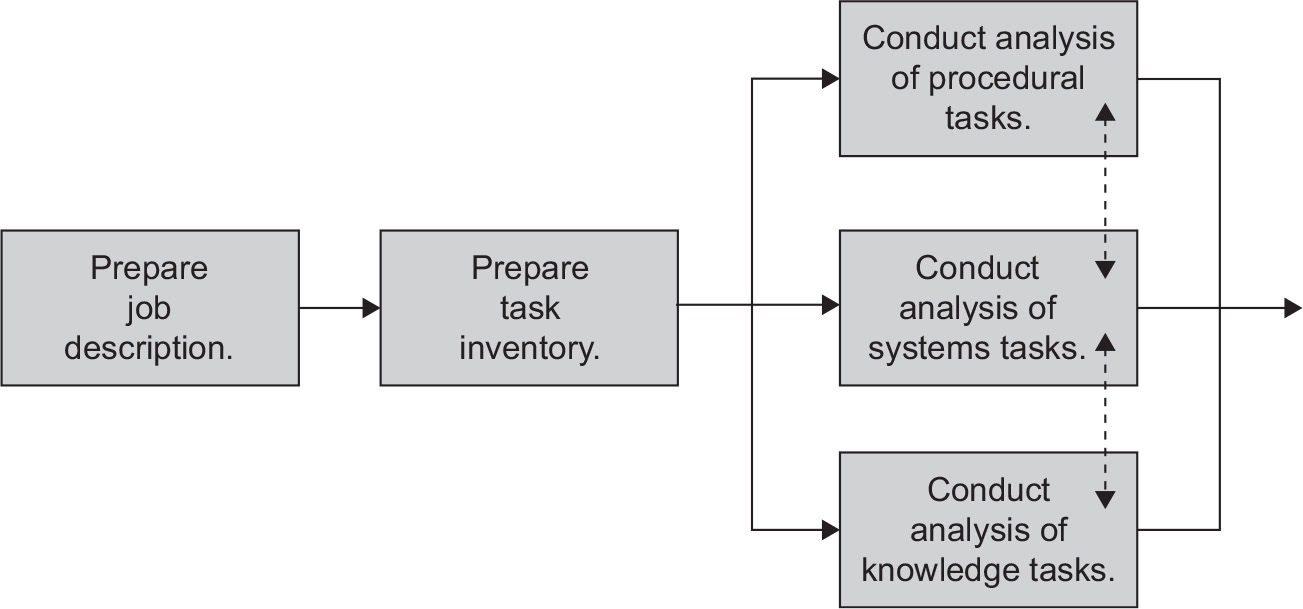

Phase 1: Analyze Two significant components: (1) diagnosing the performance requirements of the organization that can be improved through training, and (2) documenting the expertise required to perform in the workplace. The integrity of the TPS is in its connection to crucial organizational performance goals and in answering one or more of the following questions positively as a result of the program: (1) Did the organization perform better? (2) Did the work process perform better? (3) Did the individuals (group) perform better?

Figure 11.6: Diagnosing Performance

Source: Swanson, 2007a, 58.

Figure 11.7: Documenting Expertise

Source: Swanson, 2007a, 130.

The front-end organizational diagnosis is essential in clarifying the program goal and determining the performance variables that work together to achieve the goal. It requires the analyst to step back from T&D and to think more holistically about performance. This diagnosis culminates with a performance improvement proposal requiring human expertise to be a part of the improvement effort. The overall process is portrayed in figure 11.6.

Given the need for human expertise, the documentation of what a person needs to know and do (expertise) is the second part of the analysis phase. The TPS addresses job and task analysis with special tools for documenting procedural work, systems work, and knowledge work. Task analysis invariably requires close, careful study and generally spending time with a subject matter expert in their work setting. The process is portrayed in Figure 11.7.

Figure 11.8: Training Strategy Model

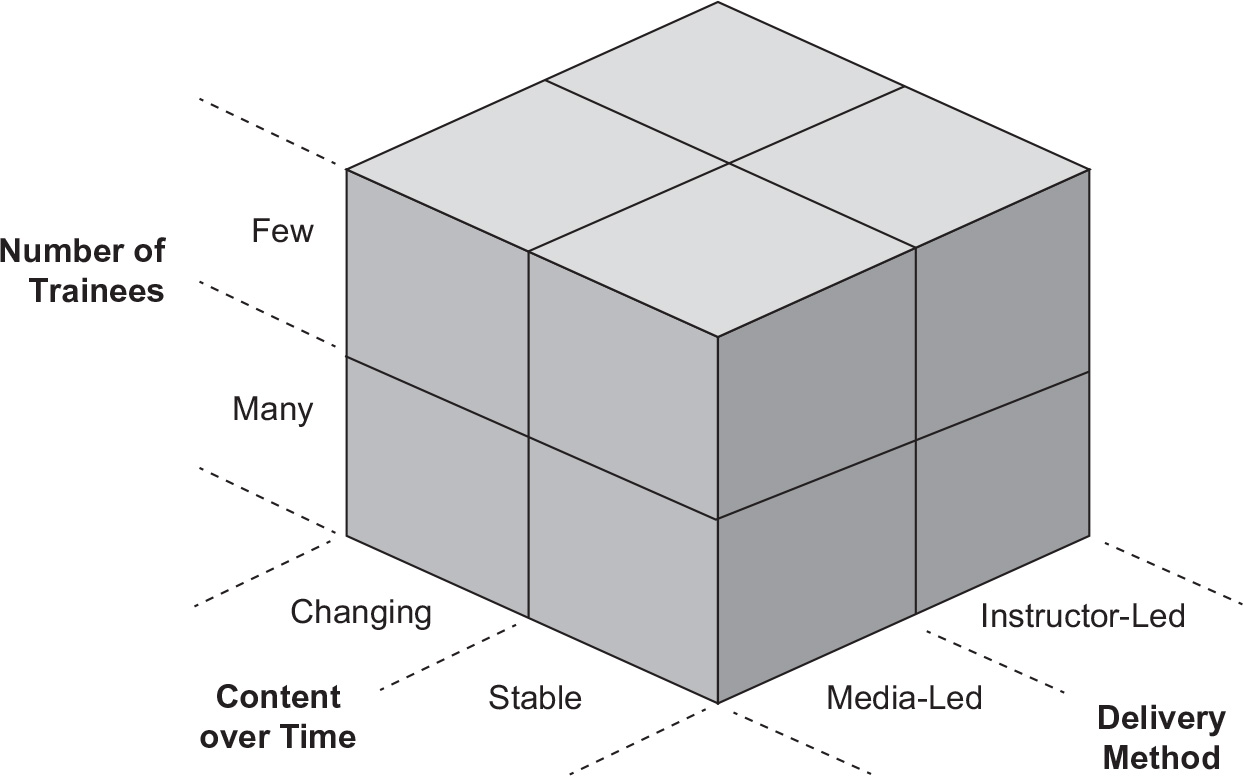

Phase 2: Design Create and/or acquire general and specific strategies for people to develop workplace expertise. T&D design is at the program and session/lesson levels. The overall design strategy needs to be economically, systemically, and psychologically sound at the program design level. Critical information that will influence the design is gathered. The “training strategy model” depicted in figure 11.8 allows the program designer to consider the critical interaction between the stability of the content, the number of trainees, and the primary method used to develop the required knowledge and expertise.

In thinking about delivery methods, one can plan using the continuum of training being “media-led” through “instructor-led.” Both will likely use media; the dividing point is when the locus of delivery control is with the instructor or within the media itself.

Media-led includes alternative technologies, such as virtual reality, internet, interactive video, computer-based training/performance support, programmed instruction (video/audio/paper), and programmed instruction/job aid (paper). In contrast, instructor-led involves off-site classrooms, on-site classrooms, structured on-the-job, and team learning settings.

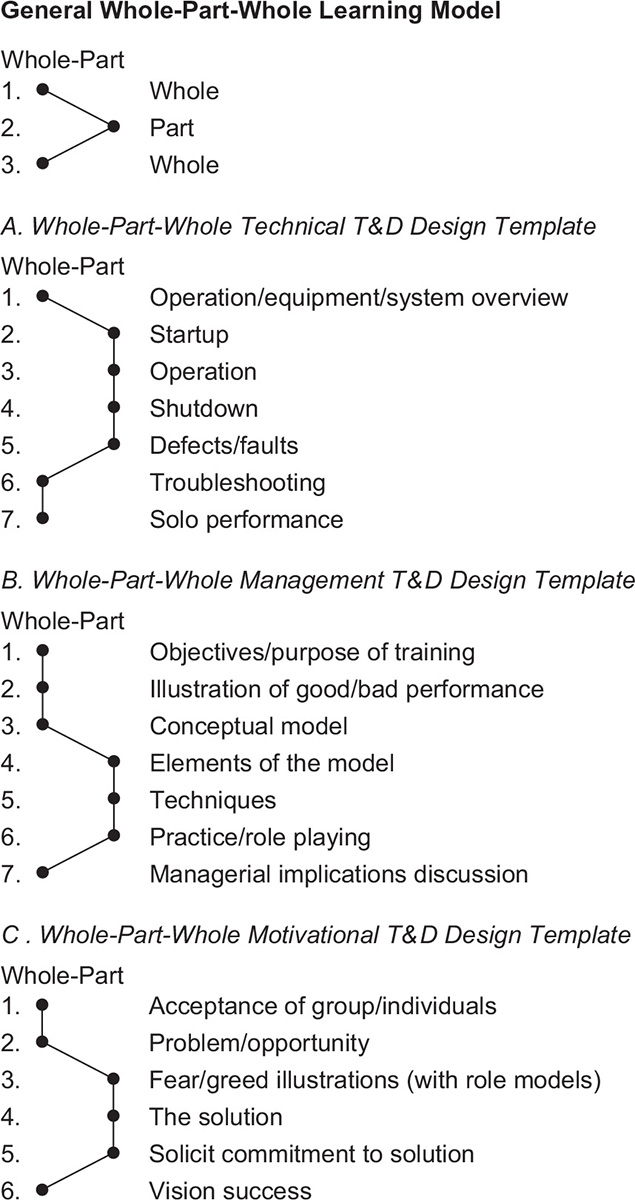

T&D Design Templates. The “whole-part-whole” learning model (Swanson and Law, 1993) serves as the basis for T&D design templates. The basic human psychological need for the “whole” (as explained by Gestalt psychology) and the need for the “parts” (as described by behavioral psychology) are utilized to structure whole-part-whole (W-P-W) learning templates. The W-P-W model can be applied at both the program design and individual lesson/session design levels.

Lesson/Session Plan Design. The lesson/session plan is the final and official document in the design phase. It combines the original performance requirement, the documentation of expertise, and the resulting training objectives into the “artful” articulation of content and method. The lesson/session plan is not a private document. It is the property of the sponsoring organization, and it should be detailed to the point that another knowledgeable trainer could take the lesson/session plan and the supporting materials and teach essentially the same content via the same method in the same period.

Phase 3: Develop Develop and/or acquire participant and instructor training materials needed to execute the training design. There is an almost unlimited range of instructor-and media-based T&D materials and media options available to the T&D profession. The development of training materials is a paradox. While the range of creative options is enormous, most training programs utilize planned materials such as those portrayed in level 2 of the following five-level portrayal:

Level 1: No planned instructor materials; no planned participant materials.

Level 2: Projected visuals; digital or paper copies of the visuals for the participants.

Level 3: Projected visuals; trainee’s print materials in the form of a structured trainee notebook (including paper copies of the visuals for the participants).

Level 4: Projected visuals; trainees print materials in the form of a structured trainee notebook (digital or paper copies of the visuals for the participants included); workplace objects and artifacts from the tasks to be learned; dynamic or interactive support materials such as video, interactive video, in-basket case, and simulation.

Level 5: Materials are designed to the level that they can mediate the development of knowledge and expertise without the need of a trainer.

There are practical reasons for producing materials at level 2. It is easy to imagine a situation where only one to two trainees are participating, and the content is unstable. In such an instance, structured on-the-job training would likely be the best method utilizing inexpensive level 2 training materials (see Sisson, 2001). In a similar vein, practical considerations are the primary basis for choosing any of the levels.

Once materials are developed, the critical issue emerges of testing T&D programs before program implementation. Organizations can approach pilot testing of training programs in five ways:

1. Conduct a full pilot test of the program with a representative sample of participants.

2. Conduct a full pilot test of the program with a group of available participants.

3. Utilize the program’s first offering as the pilot test, being sure to inform the participants of this fact and gain their support in providing improvement information.

4. Conduct a “walk-through” of the entire program with a selected group of professional colleagues and potential recipients.

5. Presenter of the program conducts a dry run by him-or herself.

Most organizations rely on 5, 4, and 3 to meet the pilot test requirements. For programs with limited offerings, options 4 and 5 are used.

Phase 4: Implement Manage individual training programs and their delivery to participants. The issues around managing and delivering T&D to participants suggest that the strategies for both have been thought through and planned into program materials.

Managing individual T&D programs should not be confused with leading or managing a T&D department. The focus here is on managing unique programs that will most likely be offered on numerous occasions by various presenters. Managing T&D programs should be considered those activities (things, conditions, and decisions) necessary to implement a particular training program. They can also be regarded as generally taking place before, during, or after the training event with time specifications recorded in weeks (or days) for the “before” and “after” periods and hours (or minutes) on the lesson plans for the “during” period of the training event.

Either a simple paper-or computer-based project management system is typically used. It requires specification of the activity, activity details, initial and completion dates, and the responsible party for each. These data can be matrixed into a management chart or placed in a simple computer database for assignments and follow-ups.

Delivery of T&D to participants is the pressure point in the T&D process. Presenters want to succeed, and participants want high-quality interaction. Critics of T&D lament that this often causes presenters to digress to gimmicks and entertainment instead of facing and managing delivery problems. One study identified the following twelve most common delivery problems of beginning trainers and the general tactics used by expert trainers in addressing those problems (Swanson and Falkman, 1997):

Delivery Problems and Expert Solutions (in Parenthesis)

1. Fear (Be well prepared; use ice breakers; acknowledge fear).

2. Credibility (Don’t apologize; have the attitude of an expert; share personal background).

3. Personal experiences (Report personal experiences; report experiences of others; use analogies, movies, famous people).

4. Difficult learners (Confront problem behavior; circumvent dominating behavior; use small groups for timid behavior).

5. Participation (Ask open-ended questions; plan small group activities; invite participation).

6. Timing (Plan well; practice, practice, practice).

7. Adjust instruction (Know group needs; request feedback; redesign during breaks).

8. Questions (Answering: anticipate questions; paraphrase learners’ questions; “I don’t know” is OK) (Asking: ask concise questions; defer to participants).

9. Feedback (Solicit informal feedback; do summative evaluations).

10. Media, materials, facilities (Media: know equipment; have back-ups; enlist assistance) (Material: be prepared) (Facilities: visit facility beforehand; arrive early).

11. Openings and closings (Openings: develop an “openings” file; memorize; relax trainees; clarify expectations) (Closings: summarize concisely; thank participants).

12. Dependence on notes (Notes are necessary; use cards; use visuals; practice).

Phase 5: Evaluate Determine and report T&D effectiveness in terms of performance, learning, and satisfaction. The TPS draws upon a results assessment system (Swanson and Holton, 1999) conceptually connected to the first phase—analysis. In effect, it is first and foremost a checkup on those three goal-focused questions from the analysis phase: (1) Does the organization perform better? (2) Does the work process perform better? (3) Do the individuals (group) perform better? With learning being an important performance variable, assessing learning in terms of knowledge and expertise is an essential intermediate goal. To a lesser extent, the perception of T&D participants and program stakeholders is viewed as necessary.

Based on an analysis of actual T&D practices, traditionally, there have been three domains of expected outcomes: performance (individual to organizational), learning (knowledge to expertise), and perception (participant and stakeholder). Focusing on a single realm changes the purpose, strategy, and techniques of intervention. If an intervention is expected to result in highly satisfied participant-learners, T&D professionals will engage in very different activities than if the expected outcome were to increase organizational performance. With organizational performance as the desired outcome, T&D professionals will spend time with managers, decision makers, and subject-matter experts close to the performance setting throughout the T&D process. If the outcome is satisfied learner-participants, T&D people will likely spend time asking potential participants what kind of T&D experience they like, will focus on fun-filled group processes, and will have facilities with pleasing amenities.

It is not always rational to think that every T&D program will promise and assess performance, learning, and perception outcomes. Furthermore, it is irrational to believe that a singular focus on one domain (performance, learning, or perception) will result in gains in the others. For example:

• An overly demanding T&D program could leave participants less than thrilled with their experience.

• Participants may gain new knowledge and expertise that cannot be used in their work setting.

• Participants can thoroughly enjoy a T&D program but learn little or nothing.

Being clear about the expected outcomes from T&D is essential for good practice. As the saying goes, “If you do not know where you are going, you will likely end up someplace else” (Mager, 1966).

LEADING THE T&D PROCESS

Lead and maintain the integrity of the training and development process. The leadership task is the most important task within the T&D effort. The training process requires strong individuals to champion the mission, goals, method, and specific training efforts in the context of the organization. To do this, the champion must articulate to all parties the outputs of training and their connection to the organization, the process by which the work is done, and the roles and responsibilities of the training stakeholders.

Outputs of Training The output of the TPS is human expertise to improve performance. Such a decision radically affects the training process and the training stakeholders. The TPS acknowledges that training by itself can develop expertise and that workplace performance is beyond the training experience alone.

• Obtaining workplace performance almost always requires line manager actions as well as training.

• Managers must be fully responsible partners in performance improvement interventions that rely on training.

Other common and less effective outputs of training have been

• Clock hours of training or the number of people trained

• Meeting compliance requirements from an external or internal source of authority

• Management and/or participant satisfaction apart from measures of knowledge, expertise, and performance

• Knowledge gains that are marginally connected to performance requirements

• Expertise gains that are marginally connected to performance requirements.

Process of Training Training professionals must have expertise in a defined training process. The TPS is one such process, and DACUM (developing a curriculum) is another popular system (https://dacum.org). Training leaders must advocate for a systematic training process based on findings from research and experience.

Training Stakeholders Expertise among the stakeholders is required to carry out the defined training process. Leaders select or develop the professional training expertise required by the defined training process. Roles and responsibilities of those working in the process—the stakeholders—must also be defined and managed (see the next section).

Individual-Focused T&D

Most traditional structured classroom T&D is organized for groups of twelve to twenty-four. In the same organizations, workplaces are generally used for continuous delivery of one-on-one training involving a trainer and a trainee. Two well-documented systems provide methods for this work that typically is provided “just-in-time” (at the time the worker needs the knowledge and expertise) and is narrow in scope (task-focused). The first method, hands-on training (Sisson, 2001), involves using fellow workers to be trainers of realms in which they are subject-matter experts. The second is structured on-the-job training (Jacobs, 2003). It involves a professional trainer engaging and preparing subject-matter experts to deliver task-level training one-on-one in the workplace.

HANDS-ON TRAINING

Sisson (2001) describes hands-on training (HOT) as a way of organizational life and not training in the traditional sense. He sees it as a tool that can become part of the natural work setting, while still dependent on following a step-by-step system—a system with trainees learning the right way of doing the job and a fellow worker instructor competent in using HOT.

Sisson presents HOT as including six steps, under the acronym POPPER (HOT POPPER) to be followed by the trainer/worker/subject-matter expert:

1. Prepare for training.

2. Open the session.

3. Present the subject.

4. Practice the skills.

5. Evaluate the performance.

6. Review the subject.

Sisson’s one-hundred-page book describing HOT POPPER can be put directly into the hands of workers taking on the role of training others in tasks they have mastered. The core arguments supporting HOT POPPER include it having (1) low costs and high returns, (2) simplicity, and (3) the belief that it adds basic order to something that is going to happen anyway—learning from each other in the workplace.

STRUCTURED ON-THE-JOB TRAINING

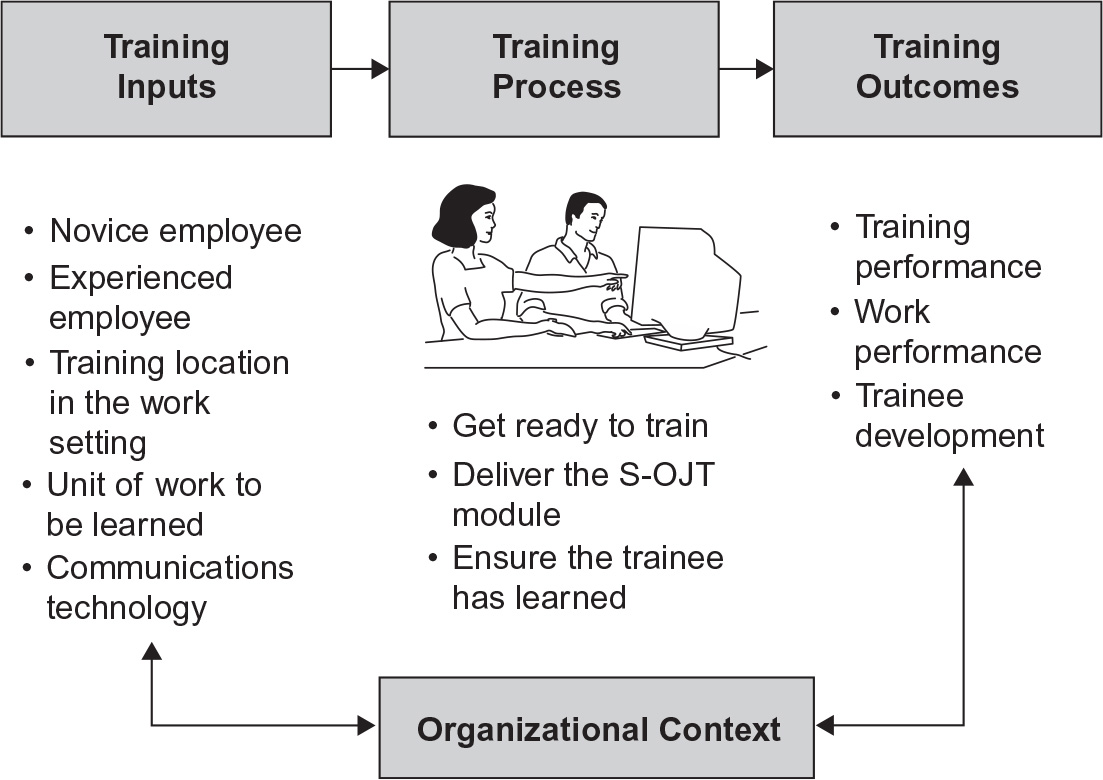

Jacobs (2003) defines structured on-the-job training (S-OJT) as “the planned process of developing competencies on units of work by having an experienced employee train a novice employee at the work setting or a location that closely resembles the work setting” (29). He estimates that 90 percent of job-specific knowledge is learned on the job (trial and error) and that more money is spent indirectly by organizations on OJT than is spent directly on structured training that takes place off the job. Furthermore, Jacobs (2003) estimates that the costs of unstructured OJT job training (no training, trial and error) consumes up to one-third of the salary paid to an employee in the first year.

The S-OJT system is illustrated in figure 11.9. The four primary elements include training inputs, training process, training outputs, and organizational context.

S-OJT relies on T&D professionals to oversee and carry out programs. Subject-matter experts are called upon as team members for content input, development, and delivery while under the direction of a T&D specialist. This level of professional oversight distinguishes it from the HOT POPPER methodology that can be placed totally in the hands of the subject-matter expert.

Figure 11.9: The Structured On-the-Job Training System

Source: Jacobs, 2003, 31.

Team/Group-Focused T&D

Team/group-focused T&D is a relatively new phenomenon compared to individual-focused T&D programs. Various titles are used—such as action learning, organizational learning, and the learning organization—and they are rooted in two thought streams. One has to do with the power of group learning versus individual learning. The second is related to the anticipated gains from creating an organizational culture that values and captures the fruits of continuous learning. These T&D options are typically pursued outside the demand for immediate performance results and anticipation of future demands. Two well-documented strategies include action learning (Yorks, 2005a) and the learning organization (Marquardt, 2002).

ACTION LEARNING

Yorks (2005a) defines action learning as “an approach to working with, and developing people, on an actual project or problem as a way to learn. Participants work in small groups to take action to solve their problem and to learn from that action. Often a learning coach works with the group in order to help members learn how to balance their work with the learning from that work” (185).

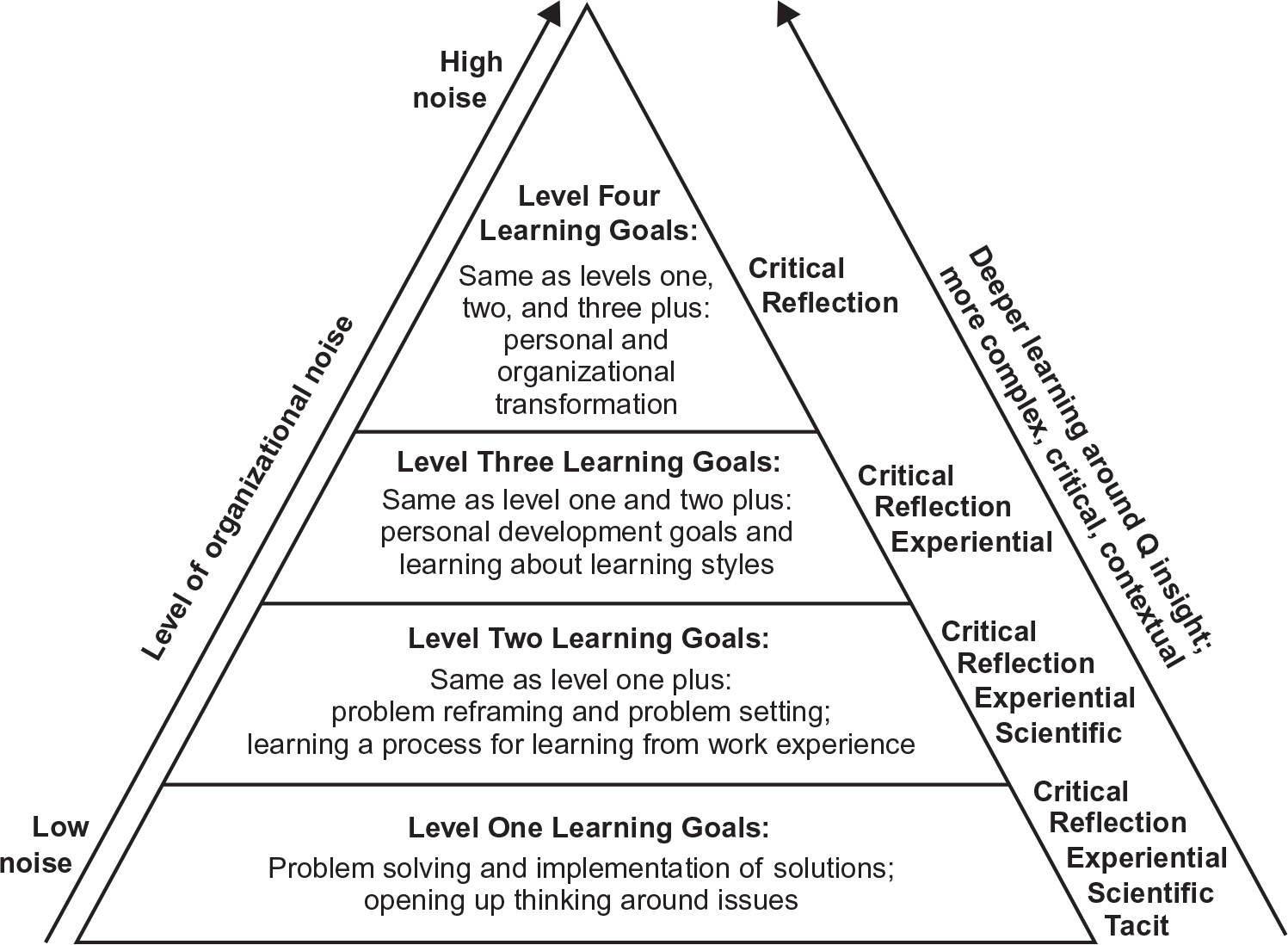

Yorks provides a work-based learning pyramid (see figure 11.10) to help practitioners make one of four program design choices based on the outcomes desired.

Figure 11.10: Work-Based Learning Pyramid

Source: Yorks, 2005b, 189.

The pyramid illustrates learning experiences that increase in depth and complexity as action learning moves up from its base from level one to level four. The interplay with the intensity of the dynamics with the host organization also increases as the levels increase. He calls this factor organizational noise.

Yorks (2005a) says that design decisions are important and that they must be in alignment with the purpose of the program, the adequacy of the support for the learning goals, and the organizational culture readiness to support the action learning program.

ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING

Marquardt (2002) bluntly states that “organizations must learn faster and adapt faster to changes in the environment or they will simply not survive. As in any transitional period, the dominant but dying species (nonlearning organizations) and the emerging, more adaptive species (learning organizations) presently exist side by side. Within the next ten years, I predict that only learning organizations will be left” (xi–xii). Marquardt goes on to list sixteen general steps in building a learning organization and the extensive cultural shift it demands:

1. Commit to becoming a learning organization.

2. Form a powerful coalition for change.

3. Connect learning with business operations.

4. Access the organization’s capabilities on each subsystem of the Systems Learning Organization model.

5. Communicate the vision of a learning organization.

6. Recognize the importance of systems thinking and action.

7. Leaders demonstrate and model commitment to learning.

8. Transform the organizational culture to one of continuous learning and improvement.

9. Establish corporate-wide strategies for learning.

10. Reduce bureaucracy and streamline the structure.

11. Extend learning to the entire business chain.

12. Capture learning and release knowledge.

13. Acquire and apply the best technology to the best learning.

14. Create short-term wins.

15. Measure learning and demonstrate learning successes.

16. Adapt, improve, and learn continuously. (211)

Training Roles and Responsibilities

T&D leaders manage and improve the training process. Having a defined process, such as TPS or S-OJT, is a critical first step. Having people with adequate expertise to function in their assigned training process roles is another critical component. Even with these conditions in place, the training process will not necessarily work or work smoothly, let alone improve.

It is important to identify the specific stakeholder roles in the training process, their responsibilities, and the process quality standards. The T&D phases and steps constitute the process. The roles, responsibilities, and process quality standard decisions could vary with specific organizations, but generally, they would include the following:

Roles

Upper management; line manager; T&D manager; program leader; program evaluator; T&D specialist; subject-matter expert; support staff; external consultant; and external provider.

Responsibilities

Leads program; manages program; produces outputs per program, phase, and/or step; determines whether phase/step level outputs meet quality standards; provides information about program, phase, and/or step; and gets information about program, phase, and/or step.

T&D Process Quality Standards Categories (applied to each T&D phase or step outputs)

Quality features; timeliness; and quantity.

Best decisions as to the specifics on how the three sets of data above interact should be made, recorded, and communicated as a means of further defining the training process to ensure the highest quality of training. These training roles, responsibilities, and quality standards decisions would approximate (or actually become) training policy. Once they are stabilized and adhered to, improvements to the training process can be based on solid data and experience.

Conclusion

T&D is a process that has the potential of developing the human expertise required to maintain and change organizations. As such, T&D can be strategically aligned to its host organization’s strategy and performance goals. T&D also can develop the expertise required to create new strategic directions for the host organization.

Reflection Questions

1. How would you define T&D and describe its relationship to HRD?

2. What is the role of informal and incidental learning in T&D?

3. What are the unique aspects of the training and development component of HRD?

4. What is the purpose of each of the five phases of T&D and the relationship between the phases?

5. How does T&D help with the organizational challenges of managing the system and changing the system?

6. Describe a hypothetical situation where using the HOT POPPER method makes the most sense.

7. Describe the basic differences between the ADDIE and TPS systems.

8. Describe a situation in your experience where action learning or organizational learning would have been appropriate and why.

Internet Resources. Instructional support materials for this chapter can be found on this website: www.texbookresources.net