CHAPTER 5

Project Management Methodology and Operations

The purpose of this chapter is to put the use of the WBS into perspective from a methodological viewpoint, including addressing the use of the WBS in each of the nine Project Management Knowledge Areas described in the PMBOK® Guide.1

The WBS is only one tool of many that are used to manage projects, but it may be the most important.

GENERIC METHODOLOGY

Project management principles have evolved to the point where a fundamental methodology is used by virtually all organizations that follow the PMBOK® Guide. This fundamental methodology applies to all projects and programs.2

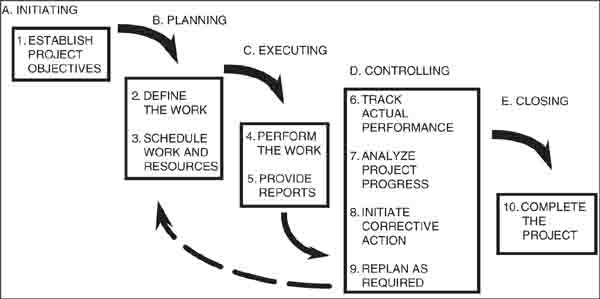

The generic or standard methodology used to implement project management relies on the 10 steps shown in Figure 5-1.

FIGURE 5-1 Basic Project Management Process

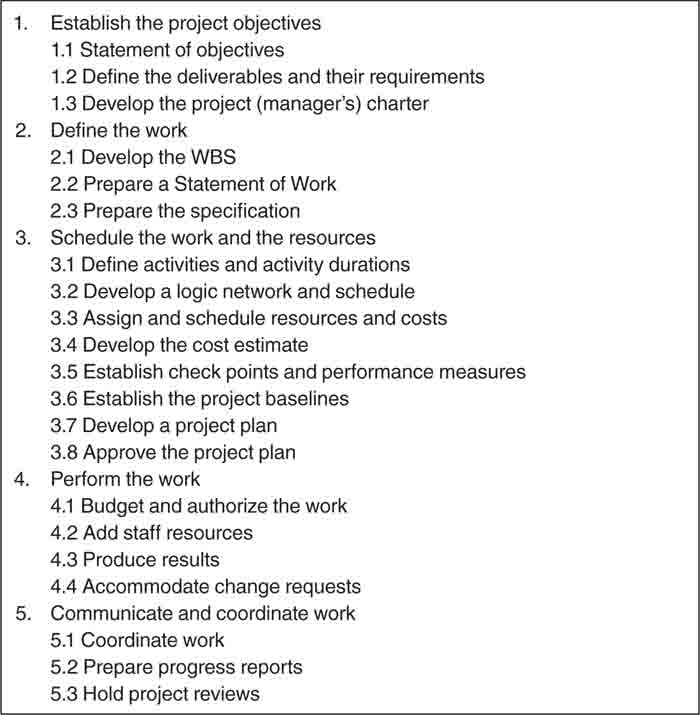

These 10 steps are subsets of the five phases of a project: A. Initiating, B. Planning, C. Executing, D. Controlling, and E. Closing. Figure 5-2 expands these basic process steps and provides the basis for a comprehensive methodology, which includes the next-level steps within each of the 10 primary steps. The WBS is the key element in the process of defining the work and depends upon knowing the objectives of the project and the nature of the final product or output.

The importance of knowing the objectives of a project before you start planning it cannot be overstated. You cannot develop a WBS, a statement of work (SOW), a schedule, or any of the other items that are part of managing the project without knowing the objectives of a project. The Cheshire Cat in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland explains very clearly to Alice the reason for knowing your objective:3

Alice: “Cheshire-Puss, would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where—” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

“—as long as I get somewhere,” Alice added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only walk long enough.”

Alice felt that this could not be denied—.

FIGURE 5-2 Expanded Methodology Steps

Step 2.1 is key to being able to define the work, after the objectives are understood. As discussed earlier, the WBS is the outline of the work to be performed and provides the structure or framework for identifying and organizing the activities of the project. Nearly all of the succeeding steps are predicated on or facilitated by the WBS. Basically, all planning and control activities are WBS-based, and you cannot control without first having a plan to measure progress against. Nor can you be comfortable that your plan is complete without following the steps described earlier and developing an effective WBS.

While this generic methodology applies to all projects, the manner in which it is applied depends upon the specific type of project and the nature of the project. For example, the emphasis on the various methodological steps varies if the project is one assigned by a supervisor or is a response to a solicitation or to a customer outsourcing the project work. The one common denominator is that a WBS is needed to define the work.

SCOPE MANAGEMENT

Scope management is the set of processes and activities performed to define the scope and content of the project and to establish the basis for managing changes in scope. The primary tool used for scope management is the WBS.

Project Charter

The project charter is one of the primary documents used to define a project and the project objectives and outputs. A project charter also establishes the general framework for implementation of the end product. A commonly used variant, the project manager’s charter, serves as the “contract” between the project manager and the project sponsor. The project charter establishes the parameters of the assignment, including resources and authority. It usually is prepared after an authorization to spend resources on a project and may include an SOW.

The project manager prepares the project charter document, which then is reviewed and approved by senior management and, in some cases, the customer. In a matrix organization, the supporting organizations must concur as well. Charters vary in size and comprehensiveness according to the size of the project and are usually from three to ten pages in length. For small projects, the project charter may be a verbal agreement; however, the project manager should create a written document that establishes that the agreement was made verbally for his or her own reference.

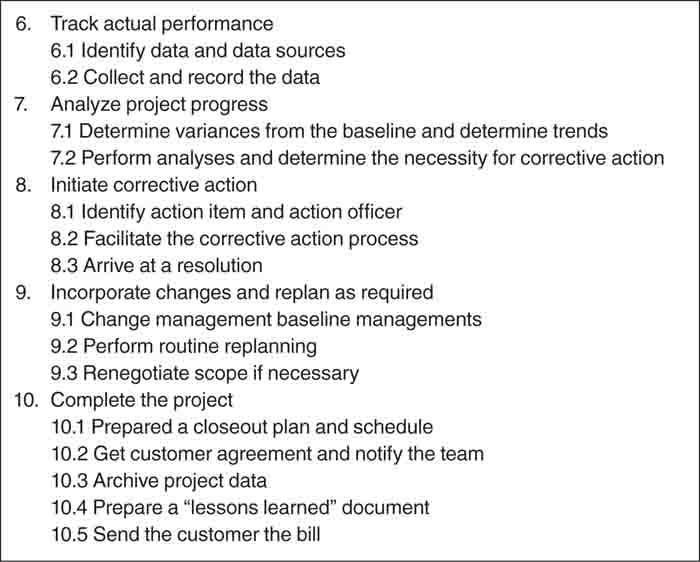

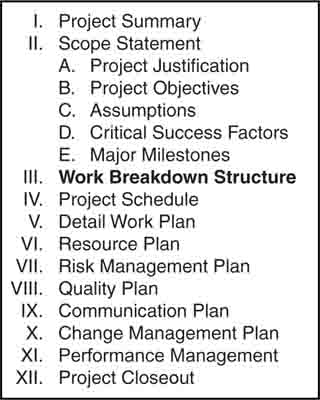

The paragraphs and sections within a project charter can vary from project to project, but the major areas that must be addressed are shown in the outline in Figure 5-3.

FIGURE 5-3 Outline of the Project Charter

The outline needs to be tailored to the project and the project environment. The charter should include all the information and guidance needed to acquire resources and to begin development of the WBS and detailed project planning. For purposes of this text, the important contents are the deliverable products, services, or results, because this information provides the basis for the development of the WBS.

The WBS provides the outline of the written SOW or scope statement and is also the framework for related items used to characterize the project.

Statement of Work

The SOW is a document that describes in clear, understandable terms what project work is to be accomplished, what products are to be delivered, and what services are to be performed. Preparation of an effective SOW requires a thorough understanding of the products and services that are needed to satisfy a particular requirement. Because the WBS is established based on the work that must be performed to deliver the end items, the WBS is used for the outline of the SOW. The WBS dictionary, with minor modifications, can readily be converted into SOW language for a contract document. A SOW expressed in explicit terms will facilitate effective communications during the planning phase and effective project evaluation during the implementation phase, when the SOW becomes the standard for measuring project performance.

When work is contracted out, as it is in many public-sector and large private-sector programs, the SOW is usually prepared only to the second or third level of the WBS for the specific work element to be procured, leaving the lower-level decomposition up to the contractor.

A well-written SOW answers the “what, why, where, when, and how” questions. What you want to buy is addressed in the introduction and scope sections, where the WBS is important. Why you want it is explained in the background section. Where the work is to be done is covered in the place of performance section. When the work is to be done is covered in the period of performance section. How the work is to be done is set forth in the technical requirements and delivery sections, supported by the applicable documents and supporting information sections.4

A DoD document, MIL-HDBK-245D, Handbook for Preparation of Statement of Work (SOW), also stresses the use of the WBS in the preparation of the SOW.5

As discussed in the previous chapter, using a standardized WBS as a template when constructing the SOW for a project helps streamline the process. Use of the WBS will also facilitate a logical arrangement of the SOW elements, provide a convenient checklist to ensure all necessary elements of the project are addressed, and direct the project to meet specific contract reporting or data deliverable needs.

TIME MANAGEMENT

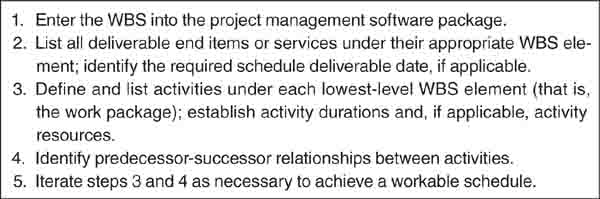

The WBS is used as the framework for planning and scheduling when projects are performed in-house or by contractors. Using project management software or scheduling forms, the schedule development process is shown in Figure 5-4.

FIGURE 5-4 Schedule Development Process

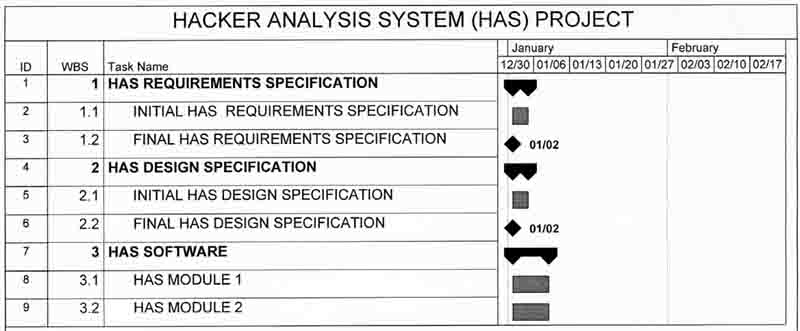

Figure 5-5 shows the WBS of the example in Chapter 2 after it has been entered into Microsoft Project Standard 2003. The WBS is used as the primary input to activity definition—step 1 of the process list of Figure 5-4.

FIGURE 5-5 Step 1 of the Scheduling Process—Enter the WBS

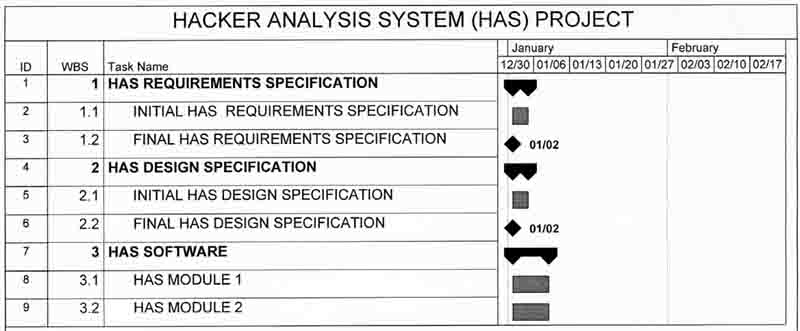

Figure 5-6 shows the same WBS but with the identification of the deliverables added as zero duration activities.

FIGURE 5-6 Step 2 of the Scheduling Process—Add Deliverables

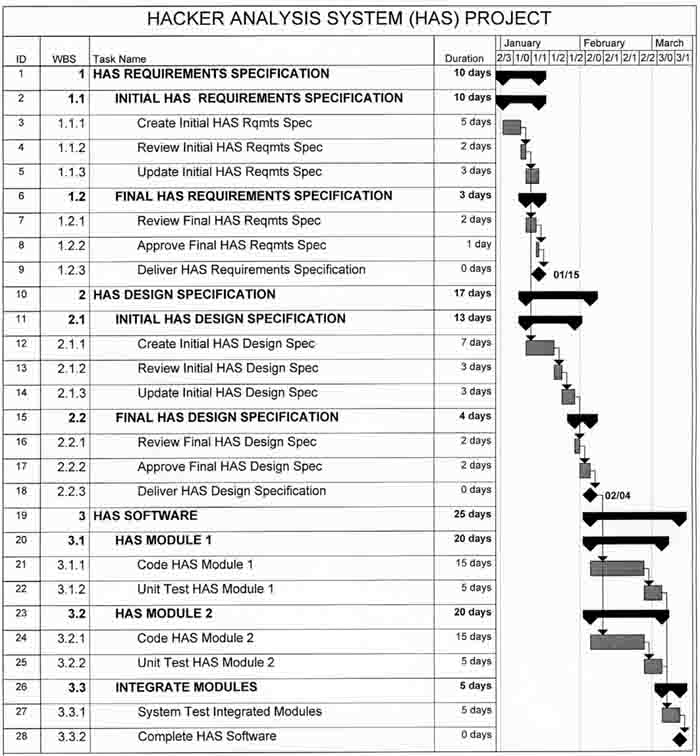

Figure 5-7 represents the final schedule after the activities and their durations are added and the activities are linked. After the WBS is completed, the process is logical, orderly, and easy.

The results of steps 3 and 4 are shown in the completed schedule in Figure 5-7. The activities identified in Chapter 2 have been added and linked to identify the predecessors and successors.

See Figure 2-14 in Chapter 2 for the final schedule, including the addition of project management activities.

Experience shows that after the WBS is entered into the software in the Gantt chart format, the activity definition actually can be performed faster than most people can type the descriptive activity names. Duration information, resource information, and linkages need not be entered in any particular order and often are entered concurrently with activity definition. The important thing is to get the complete WBS entered into the computer program down to the work package level; then the rest of the activity definition proceeds rapidly and comprehensively.

Experience also shows that revisions to the WBS occur in this process as activities are defined. The WBS is not finalized until the project is baselined.

FIGURE 5-7 Completion of Steps 3 and 4 of the Scheduling Process

COST MANAGEMENT

There are four special applications of the WBS in cost management:

![]() Bottom-up cost estimation

Bottom-up cost estimation

![]() Collection of historical data

Collection of historical data

![]() Chart of accounts linkage

Chart of accounts linkage

![]() Earned value management system implementation

Earned value management system implementation

![]() Budgeting

Budgeting

BOTTOM-UP COST ESTIMATION

Bottom-up cost estimation is the most commonly used technique for estimating the total cost of a project. As the name implies, it is a summation of the estimated cost of all the individual activities of the project. The WBS is normally used as the framework for preparing the initial comprehensive estimate and subsequent budgets.

The estimation process is relatively simple; each activity is identified, as discussed in “Time Management” earlier in this chapter, and the responsible person or organization is requested to provide an estimate of the work to be performed. These activity-level estimates are collected and summed to provide the total project estimate.

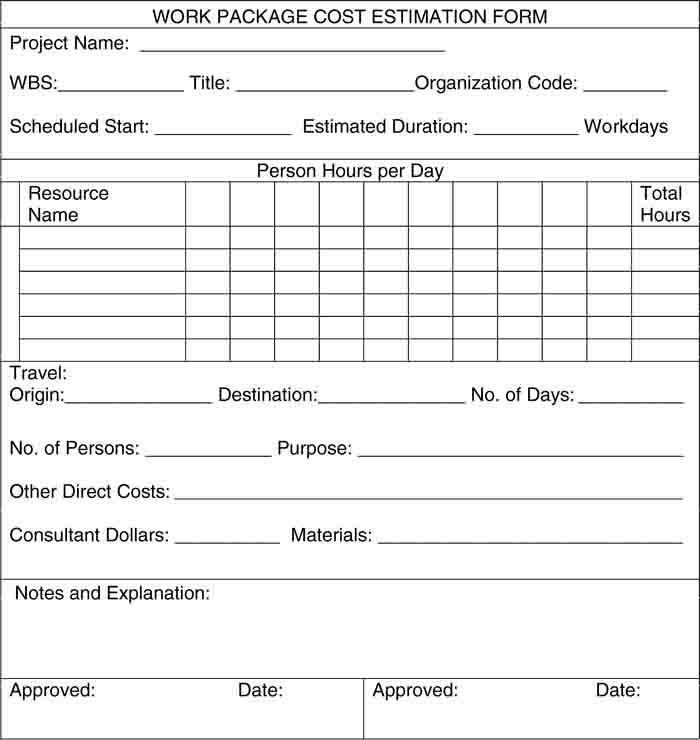

On larger projects, work packages or cost accounts are used as the building blocks for the cost estimate.

Figure 5-8 is an example of a typical form used to collect work package data according to WBS descriptor for bottom-up estimation. The same form, with minor modification, can be used for activity-level estimating. It is the comprehensiveness of the properly developed WBS that ensures that all costs are included. This form is then used to enter the data into the computer system. Alternatively, of course, experienced personnel can enter these data directly into the computer during the scheduling process.

FIGURE 5-8 Sample Work Package Cost-Estimating Form

For government projects, when it is necessary to provide cost estimates for large projects to be contracted out and parametric data or other top-down estimating data are not available, the government planner must use bottom-up cost estimation. In such cases, the WBS needs to be developed to a more detailed level than for the procurement SOW so that a reasonable estimate can be developed. It can also be necessary to develop a schedule like the one shown in Figure 5-7. The process is no different than it is for industry. To the extent that they are available, experienced people are asked to provide estimates for the costs of each work package or activity.

The term WBS has become a common term in all fields related to construction cost engineering, including construction cost estimating, scheduling, and project cost control. A well-defined WBS is the backbone of good construction cost-estimating software and can take several forms, including the breakdown of items within an estimate, the layout of groups within a schedule, or the roll-up of accounts within a cost report. The process of estimating construction costs usually starts with a client’s desire to break down a tender into definable pay items, which is then followed by the project manager’s wish to schedule activities of work in a logical and efficient manner and the contract cost control engineer’s goal of tracking and forecasting costs. In each case, a properly organized WBS is required.6

collection of Historical Data

One of the purposes of the DoD military standard, Work Breakdown Structures for Defense Materiel Items, originally published in 1968, was to be able to collect data for the seven types of military systems using a common framework. (This is also one of the goals of the FAA and Caltrans standard WBSs presented later.)

To achieve this goal, the use of a specified and standard WBS is required for the first three levels of each system. The DoD Handbook states: “Using available data to build historic files to aid in the future development of similar defense materiel items is a very valuable resource.”7

Included in the handbook are definitions (a WBS dictionary) of each Level 1 through Level 3 WBS element, which further assist in ensuring that interpretations of the content of each element are consistent from project to project.

In many organizations, the products and projects are similar. For example, for an engineering firm that specializes in designing and constructing highway bridges, the WBS for each bridge or type of bridge would be similar whether the bridges were built in New Hampshire or New Mexico. Similarly, a software firm that specializes in designing and implementing relational databases would go through the same results-oriented WBS stages for each customer. It is to companies’ advantage to develop standard WBSs and templates, at least for the top levels, for the purpose of collecting historical cost data, and perhaps other data as well. These data can then be used to assist in the cost estimation activity for new projects in the feasibility phases and to provide an initial top-down estimate for any similar proposed project. Highly sophisticated organizations are able to develop cost-estimating relations (CERs) using multiple regression techniques.

Chart of Accounts Linkages

The chart of accounts maintained by the accounting organization does not normally relate directly to the WBS. The WBS is output-oriented, and the chart of accounts identifies expense or cost categories that are inputs to the organization. Typical accounts are labor, material, and other direct cost accounts such as those listed as inputs in Figure 2-16. For cost management, the project manager needs to be able to relate the various categories of labor, material, and direct cost items to the appropriate project, cost account, and/or work package for proper allocation of incurred costs. The extent of the linkage depends upon the necessity to control project costs, the level of control that is required, and the capability of the accounting system.

For private-sector or government projects that use a performance management system based on ANSI/EIA-748, there can be an impact from so doing on the chart of accounts. The EIA standard states:

3.6 Accounting Considerations

The EVMS is not an accounting system, and EVMS guidelines do not suggest changes to accepted accounting practice. The EVMS will use actual cost data from the company accounting system as appropriate for accurate reporting of program costs and performance. The establishment of work orders and other aspects of the accounting process must be coordinated with the establishment of control accounts and other aspects of the budgeting process so that direct comparison and analysis can be done.8

Thus, to implement an EVMS, the accounting system must be able to collect actual incurred costs for each control account. As discussed earlier, control accounts are established at the lowest level of the WBS. These would thus need to be identified in the chart of accounts or an addendum to the chart of accounts.

Earned Value Management System Implementation

Many government and large private-sector projects require a performance-based management system such as EVMS. As required for government projects, this means each contractor with a project meeting the requirements for EVMS applications must have:

. . .a documented, systematic process for program management, which includes integration of program scope, schedule and cost objectives, establishment of a baseline plan for accomplishment of program objectives, and use of earned value techniques for performance measurement during execution of the program. For the acquisition phases of the program, the system is established and applied by the contractor(s) and must meet the requirements of ANSI/EIA Standard 748, Earned Value Management Systems. For those parts of the project accomplished by Government personnel or in an operational (steady state) mode, a performance-based management system must be established, using EVMS where possible to measure achievement of the cost, schedule and performance goals.9

EVMS requires a WBS for its implementation. On August 17, 1999, the DoD adopted the ANSI/EIA-748 EVMS standard for use on defense acquisitions. In February 2007, the DoD Undersecretary of Defense recognized for use the National Defence Industrial Association (NDIA) Earned Value Management Systems Intent Guide, dated November 2006, when interpreting the intent of the 32 guidelines in the ANSI/EIA-748 standard. The first guideline in this document addresses the WBS as the “basic building block for the planning of all authorized work” and goes on to describe the use of the WBS and relation to scope exactly as presented in this book.10

EVMS cannot be implemented without an effective WBS. As indicated by the DoD, for example, in its EVMS Implementation Guide:11

2.2.2.1 Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). The program WBS is a key document that is developed by the PM [government program manager] and systems engineering staff very early in the program planning phase. The WBS forms the basis for the statement of work (SOW), systems engineering plans, IMS, EVMS, and other status reporting. (See MIL-HDBK-881, Work Breakdown Structure Handbook, for further guidance.)

The reader should note that although this section uses DoD terminology, requirements, and examples, this concept also applies to other government organizations and private-sector situations for large projects or where an enterprise-level project management office (PMO) provides support and guidance to several programs within the enterprise. It is also easy for an enterprise that uses EVMS internally to adapt DoD guides and procedures to its own usage or to apply EVMS to the work done by major subcontractors using the DoD methodology and documentation.

In Section 2.2.5.2, the EVMS Implementation Guide describes the WBS that is prepared by the government program manager.12 A summary of those paragraphs is as follows:

![]() The program WBS contains all WBS elements needed to define the work of the entire program, including Government activities. The contract WBS (CWBS) is the Government-approved WBS, for reporting purposes and its discretionary extension to lower levels by the contractor, in accordance with Government direction and the SOW. It includes all the elements for the products (hardware, software, data, or services) that are the responsibility of the contractor.

The program WBS contains all WBS elements needed to define the work of the entire program, including Government activities. The contract WBS (CWBS) is the Government-approved WBS, for reporting purposes and its discretionary extension to lower levels by the contractor, in accordance with Government direction and the SOW. It includes all the elements for the products (hardware, software, data, or services) that are the responsibility of the contractor.

![]() The development of the CWBS is very important to the effectiveness of an EVMS. The WBS is the basic structure for EVMS data collection and reporting, and it should be reflected in the detailed activities in the Integrated Master Schedule, IMS. A too detailed or poorly structured CWBS can increase the cost of implementing and maintaining an IMS on a program.

The development of the CWBS is very important to the effectiveness of an EVMS. The WBS is the basic structure for EVMS data collection and reporting, and it should be reflected in the detailed activities in the Integrated Master Schedule, IMS. A too detailed or poorly structured CWBS can increase the cost of implementing and maintaining an IMS on a program.

![]() A preliminary CWBS should be included in the solicitation and is usually specified to Level 3. The project manager should exercise considerable care in its development, because providing too much detail to the contractor may have the adverse impact of restricting design trade space. The CWBS and dictionary requirements should be described in the SOW and called out on a contract data requirements list (CDRL) using Data Item Description (DID) DI-MGMT-81334B.

A preliminary CWBS should be included in the solicitation and is usually specified to Level 3. The project manager should exercise considerable care in its development, because providing too much detail to the contractor may have the adverse impact of restricting design trade space. The CWBS and dictionary requirements should be described in the SOW and called out on a contract data requirements list (CDRL) using Data Item Description (DID) DI-MGMT-81334B.

![]() The preliminary CWBS is expanded to lower levels after contract award by the contractor to reflect all work to be accomplished on the contract and to facilitate management, data collection, and reporting. There should be only one WBS that is used as the basis for all contract reporting. That is, a common WBS that follows the latest version of MIL-HDBK-881 is required for the contract performance report (CPR), the IMS, and the Contractor Cost Data Report (CCDR). The contractor should keep the CWBS dictionary current at all times and provide updates to the Government Project Manager, as specified in the CDRL.

The preliminary CWBS is expanded to lower levels after contract award by the contractor to reflect all work to be accomplished on the contract and to facilitate management, data collection, and reporting. There should be only one WBS that is used as the basis for all contract reporting. That is, a common WBS that follows the latest version of MIL-HDBK-881 is required for the contract performance report (CPR), the IMS, and the Contractor Cost Data Report (CCDR). The contractor should keep the CWBS dictionary current at all times and provide updates to the Government Project Manager, as specified in the CDRL.

![]() For contracts that require contractor cost data reporting, the CWBS is also contained in the approved Cost and Software Data Reporting (CSDR) Plan that is included in the solicitation. The CSDR Plan is developed, approved, and maintained in accordance with DoD 5000.4-M-1, Cost and Software Data Reporting Manual.13

For contracts that require contractor cost data reporting, the CWBS is also contained in the approved Cost and Software Data Reporting (CSDR) Plan that is included in the solicitation. The CSDR Plan is developed, approved, and maintained in accordance with DoD 5000.4-M-1, Cost and Software Data Reporting Manual.13

EVMS requires a detailed WBS and a close relationship between the WBS and the enterprise’s accounting system at the work package level. Ordinarily, cost accounts are established at the lowest level of the WBS at which actual costs are collected and compared to budgeted costs for particular organizations. Within cost accounts, work packages are identified, planned, and budgeted.

When implementing EVMS, the organization must be able to formulate and determine status on a monthly basis for each cost account established in the WBS. Four types of data are required for earned value/performance measurement:

![]() Budgeted Costs for Work Scheduled —BCWS, that is, the planned value

Budgeted Costs for Work Scheduled —BCWS, that is, the planned value

![]() Actual Costs for Work Performed—ACWP, that is, actual costs

Actual Costs for Work Performed—ACWP, that is, actual costs

![]() Budgeted Costs for Work Performed—BCWP, that is, earned value

Budgeted Costs for Work Performed—BCWP, that is, earned value

![]() Estimate at Completion—EAC14

Estimate at Completion—EAC14

The primary report used for analysis of performance in EVMS is called the Cost/Schedule Status Report. It includes the four types of data plus calculated cost and schedule variance data for each WBS element, from the cost account level up to the total project level.

More information on earned value management systems is available at http://www.acq.osd.mil/pm.

Budgeting and Work Authorizations

Just as cost estimates are prepared using the WBS as the framework, budgets and work authorizations are similarly developed and coordinated after the go-ahead for the project is given. Budgets are plans and are issued to organizations using work authorization forms, as discussed earlier. Budgets then become part of the cost baseline for measuring performance.

COMMUNICATIONS

The WBS can provide the framework for identifying and organizing the communications mechanisms used on a project. Discussions of the project, and parts of the project and explanations of project work, are facilitated when the WBS is used as an outline that identifies the topic under discussion and relates the particular WBS element to the work as a whole. All reporting requirements for the project should be consistent with the WBS and WBS numbering system. It is common for customers or sponsors to require progress reports to be structured by WBS Level 2 or 3 elements.

Project reviews are frequently structured according to specific WBS elements and, because most cost and schedule reports relate to WBS elements, it is a common framework. Another framework is the OBS. The author has worked on a project where the action item tracking system uses the WBS number as one of the data elements for sorting and monitoring open items.

Integrated baseline reviews (IBRs) are performed primarily to enable project management to understand the risks inherent in the performance measurement baseline (PMB) and the management processes.15 The objective of the IBR is to confirm that (1) the PMB captures the entire technical scope of work, (2) work is scheduled to meet project objectives, (3) risks are identified, (4) the proper amount and mix of resources have been assigned to accomplish all requirements, and (5) management processes are implemented. The IBR is an essential component of an EVMS, and the review is organized around a WBS framework.

Project correspondence is also expected to refer to WBS numbers when discussing areas of project work, and correspondence reference numbers frequently are WBS-based. Correspondence tracking systems have a WBS field for organizing correspondence. Filing systems consist of a day file for copies filed by date and a subject file that uses the WBS number where applicable.

On large, complex projects, the contract line items, configuration items, contract SOW tasks, contract specifications, technical and management reports, and potential subcontractor responses would all be related to the WBS numbering system.

For purposes of team building and developing as accurate a WBS as possible, it is recommended that WBS development be a team effort. Such an effort has the added advantage of providing for a team discussion of all the elements and for an improved understanding of both the work to be done and where each individual fits within the overall project. Some geographically dispersed organizations use videoconferencing techniques to develop the WBS for new projects and are thereby able to receive input from the most experienced people company-wide.

PROCUREMENT MANAGEMENT

When a product or service is to be procured or outsourced, the customer should provide the top-level WBS for the product or service in the request for proposal (RFP).16 This task is accomplished in two ways: One way is to specifically include the WBS in the solicitation, and the second way is to use the WBS as the outline of the SOW. Even if the customer is not familiar with WBS concepts, an experienced bidder will derive the WBS from the SOW in the solicitation and construct the project planning and cost estimation around the SOW. It is therefore incumbent upon the customer to provide an effective WBS.

In some acquisition activities of the U.S. government, especially since 1996, the RFP may include a comprehensive statement of objectives (SOO). This statement eliminates a detailed SOW from the RFP and puts the responsibility for the development of the SOW on the organizations responding to the RFP.17 The philosophy is equivalent to providing a performance specification rather than a detailed specification.

In this scenario, the government SOO includes more background information and information on the objectives and purpose of the solicitation than normally would be in an objective statement that was complemented by an SOW. This approach requires the prospective contractor to define the contract WBS, the SOW tasks, and sometimes the delivery schedule for the primary items.18 For government SOOs, the website that provides a source of acquisition information is http://www.acqnet.gov/Library/OFPP/BestPractices/pbsc/home.html. A link on that page goes to the “Seven Step Guide to Performance-Based Services Acquisition.” Within the steps is the description of how to create and use a SOO.

Providing the WBS in the solicitation, however, enables the different bidders to use the same framework for planning, cost estimating, and responding to the RFP, which facilitates the evaluation and source selection process.

The SOW, like the WBS, often is more complex than it appears on the surface, especially when it is used as part of a solicitation or contract.19 Although having an outline before you begin to write is preferable, many people do not use outlines and are more comfortable drafting the SOW from scratch or modifying an existing SOW without a logical framework; this is definitely not the recommended approach. However, if the SOW is drafted without an outline or a WBS, it is necessary to analyze the after-the-fact outline of the SOW to make sure it meets all the requirements of an effective WBS.

There are four principal reasons for the great importance of having a harmonized WBS and SOW: (1) They help ensure that all the work to be outsourced is identified and described, including the bidder’s project management activities; (2) the project control mechanisms will be more effective; (3) they provide a framework for submittal of cost estimates that facilitate analysis; and (4) they provide a framework for effective communication between the buyer and seller. It is important to note that after the contract is signed it may be very expensive to make changes if items were inadvertently omitted, or it may not be possible to collect desired data if the contract SOW is poorly structured. Contractors like to “get well” on changes when they have underestimated project costs.

If only a part of the project or program is to be outsourced, that portion of the project is usually a discrete work package represented in the project WBS. For example, a project for building a house could have the HVAC system as a discrete element, which is clearly identified and easily defined. The WBS facilitates communication and simplifies the planning and control on a large project where many work elements may be subcontracted. Examples are included in Part III of this book.

The individual WBS element(s) from the project WBS that defined the work to be performed under a proposed subcontract would be selected by the project manager for inclusion in a draft RFP. This is the time for open dialogue between the customer and potential contractors. Innovative ideas or alternative solutions should be collected for inclusion in the final WBS and RFP. One element of the RFP should be a CWBS and the initial CWBS dictionary for the procured item or service. The RFP should instruct potential contractors to extend the selected subcontract WBS elements in order to define the complete subcontract scope.

Contractors develop the CWBS to the level that satisfies the critical visibility requirements of both project and subcontract management and does not overburden the management control system. They submit the complete subcontract WBS with their proposals. The proposal should be based on the WBS in the RFP, although contractors may suggest changes needed to meet an essential requirement of the RFP or to enhance the effectiveness of the subcontract WBS in satisfying program objectives.

For a comprehensive discussion of the entire procurement process, see R. Marshall Engelbeck’s Acquisition Management.20

QUALITY AND TECHNICAL PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

There is limited interaction between project quality and technical performance management and the WBS, except for using the WBS element identification system to communicate areas of the project where there are quality or technical performance interests.

Another exception is the numbering system used for a specification tree on some large, complex systems projects.

A specification tree structures the performance parameters for the system or systems being developed into a series or a hierarchy of specifications. It subdivides the system into its component elements and identifies the performance objectives of the system and its elements. The performance characteristics are explicitly identified and quantified. This subdivision is the same as the decomposition in the Product WBS.

When completed, the specification tree represents a hierarchy of performance requirements for each component element of the system for which design responsibility is assigned. The WBS numbering is usually used to identify the elements where performance specifications are required. Because specifications may not be written for each element of the WBS, the specification tree usually maps only to the product-related elements of the WBS.

HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Project human resource management consists of the set of activities required to effectively organize and utilize the people who are assigned to and who are supporting the project. Because, as stated before, the WBS is not an organizational chart, there is limited use of the WBS in this function. The exception is the establishment of integrated project teams (IPTs), as discussed in this section. These teams are organized around WBS elements and focus on the integration of various disciplines to improve the management and performance of the outputs of the project.

Team Building

Development of an effective WBS is not as straightforward as it may first appear, as has been discussed in this book. Alternate WBSs were discussed previously, and in many chapters information is provided on the preferred approach to preparing a WBS. A major obstacle in organizations is the culture of the organization, especially if organization and input-oriented frameworks inaccurately referred to as WBSs have become common.

Organizations develop a “normal” way of doing business; changes, even obvious improvements, are not always easy to make. Strategies such as those discussed by Kotter are necessary for the introduction of change in cultures.21

One of the best methods for starting to build a project team is using the development of the initial project WBS as the means of building a team. Doing this has three advantages: (1) The new team quickly becomes involved in defining the project and project scope, and therefore internalizes the project; (2) the expertise of the team is utilized to help ensure that all the work that needs to be performed is represented in the WBS—that the WBS is complete; and (3) the WBS becomes the framework for communicating information about the project.

The resource assignment matrix is one of the tools used to plan the use of human resources. The matrix is an array of organization versus WBS and work packages that shows who is responsible for specific assignments on a project and the specific type of responsibility, for example, perform, approve, review, coordinate, and so on.

Integrated Product Teams

Many DoD programs are managed using the integrated product and process development (IPPD) concept, with program integrated product teams (PIPTs) established largely along the hierarchy of the Product WBS. The use of IPTs is often a contract requirement intended to integrate the DoD and contractor organizations in focusing on specific output areas.

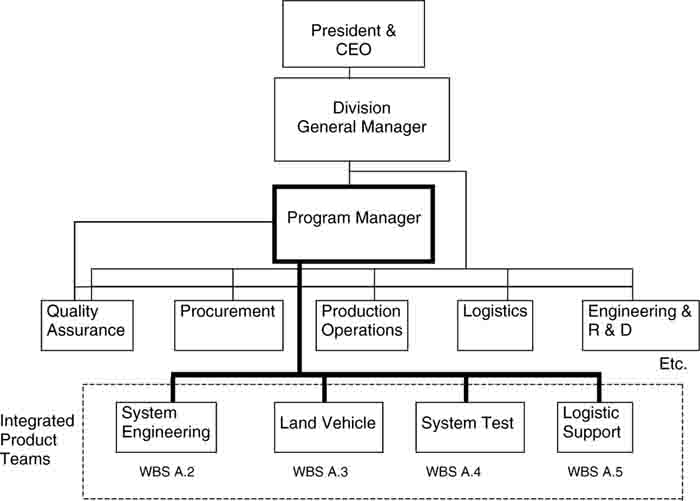

Figure 5-9 shows the organization of IPTs in a program office of a typical contractor for a government product.

FIGURE 5-9 Program Organization with IPTs

As shown in the figure, four teams that report to the program manager may be established, based on the WBS.22 IPT members on each team have complementary skills and are committed to a common purpose, performance objectives, and approach for which they hold themselves mutually accountable. This organizational structure also represents the internal customer organization.

Members of an integrated product team represent technical, manufacturing, business, operations, and support functions and organizations that are critical to developing, procuring, and supporting the product and the particular team. Having these functions represented concurrently enables teams to consider more and broader alternatives quickly and facilitates faster and better decision making.

After being assigned to a team, an IPT member changes from being a member of a particular functional organization that focuses on a given discipline to being a team member who focuses on a product and its associated processes. Each individual brings his or her expertise to the team and understands and respects the expertise available from other members of the team. Team members work together to achieve the team’s objectives.

It is critical to the formation of a successful IPT that: (1) All functional disciplines influencing the product or WBS area throughout its lifetime are represented on the team; (2) a clear understanding of the team’s goals, responsibilities, and authority is established among the division general manager, program and functional managers, and the IPT; and (3) resource requirements such as staffing, funding, and facilities are identified. These requirements may be defined in a team charter that also provides guidance.

A product-oriented WBS is essential to providing the framework for determining what teams should be established and to identifying their roles. The WBS dictionary provides partial information on their missions.

RISK MANAGEMENT

Project risk management “includes the processes concerned with conducting risk management planning, identification, analysis, responses, and monitoring and control on a project.”23 The WBS provides a logical structure for this process.

Good project management principles require that risk management methodologies be used on projects. Many government project managers routinely prepare risk management plans for their projects or require contractors to prepare them.

The requirement to perform risk management is passed down to project managers. Risk management plans are a common contract requirement.

There are many good books written on the subject of project risk management. The DoD Acquisition Deskbook, Section 2.5.2, provides general guidance and advice in all areas of risk management. This information is useful for private-sector and government projects. Section 2.5.2.4 of the Deskbook contains information about the development of a risk management plan.

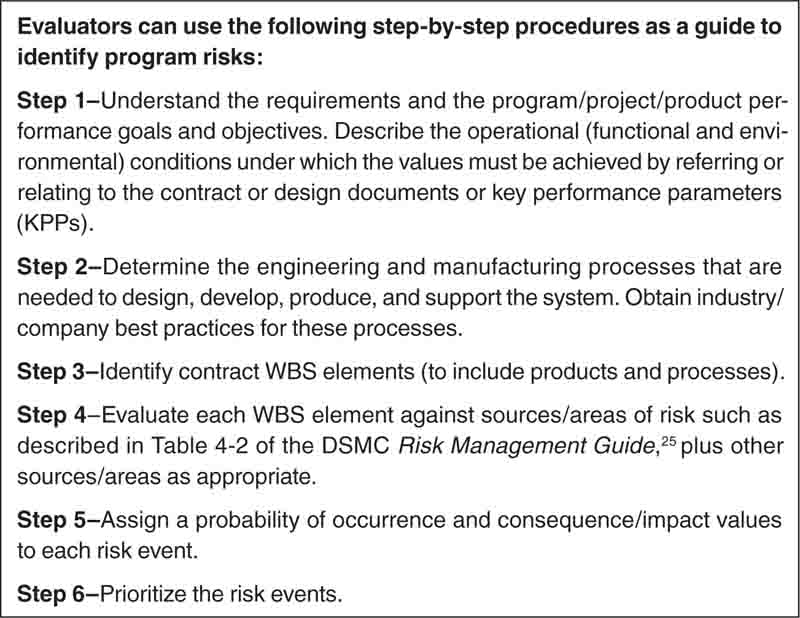

Figure 5-10 presents the recommended steps to perform to identify risks.24 Risk identification is just one step in the risk management process.

FIGURE 5-10 Risk Identification Process

The WBS is an essential component of risk management because it provides a framework for identifying risks, assessing risks, and subsequently monitoring risk items. An effective, product-oriented WBS is an essential tool in those activities.

The WBS is important in project risk management. It provides an input to risk management planning when the WBS is used as a tool in the development of the risk management plan. The risk management plan describes how risk identification, qualitative and quantitative analysis, response planning, monitoring, and control will be structured and performed during the project life cycle.

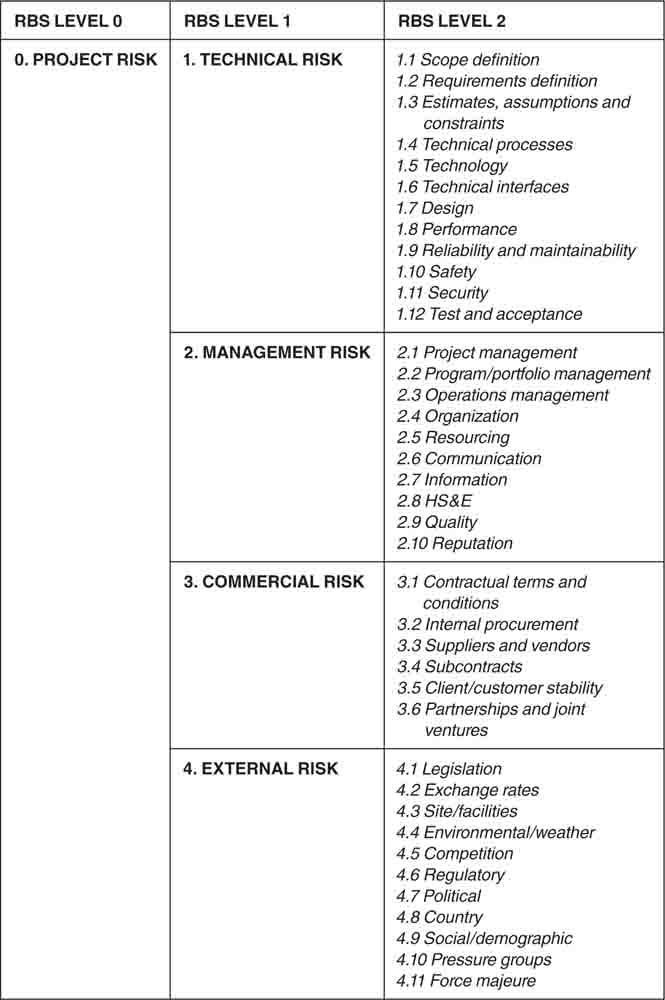

Hillson and Simon recommend the use of a Risk Breakdown Structure (RBS) to assist in the preparation of a risk management plan. In this use, the hierarchical logic of the WBS is followed, and the RBS acts as a checklist for discussion when identifying risks and for other purposes, as described in their book. Figure 5-11 shows a sample RBS.26

The primary role of the WBS is to provide a roadmap or checklist of the elements that involve project risk as a basis for discussion in the risk identification phase and to identify possible risks that require analysis and monitoring. The WBS, combined with the RBS, as shown in Figure 5-11, provides a dual checklist of project work elements and types of risks to consider.

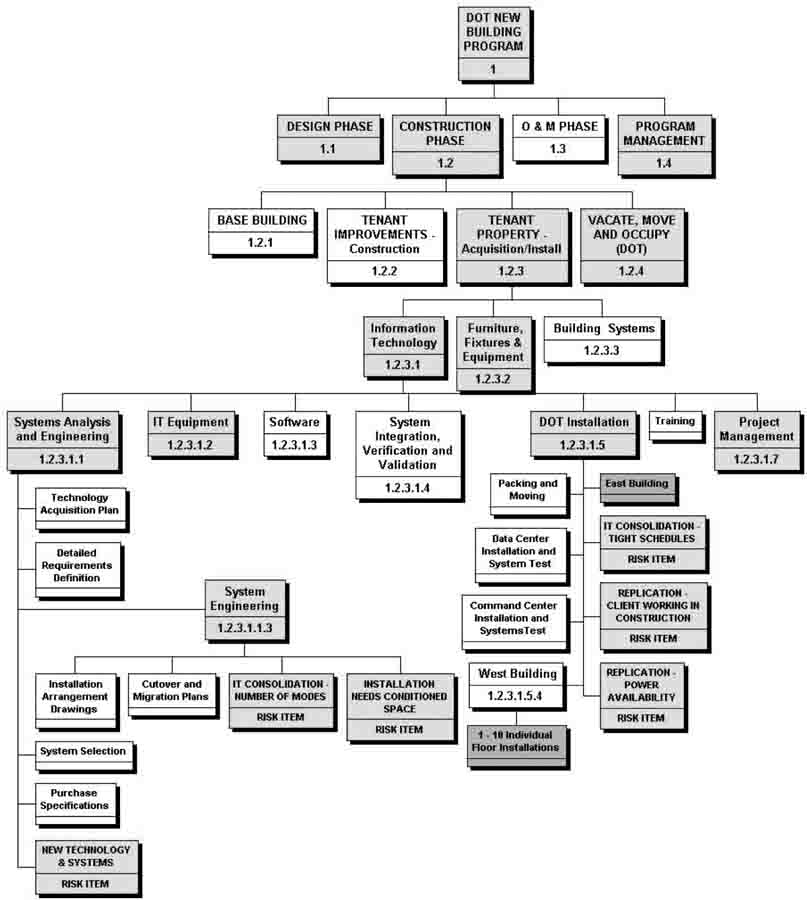

The resulting WBS that identifies the risk items is also referred to as the RBS. Figure 5-12 shows the result of the risk identification process. In the figure, the boxes that were the areas where risks were identified and mitigation implemented are identified as “Risk Items.” These items were identified through a series of interviews with senior and experienced project personnel from both the customer and the contractor staff. It was a government project, and all the work was contracted out, as is customary. The purpose of the risk analysis was to identify risks that were the primary concern in areas of responsibility of the government customer, and to do this relatively early in the project. A separate risk management program was implemented using other tools that focused on the actual construction aspects of the project and on scheduling risk probabilities.

FIGURE 5-11 Sample Risk Breakdown Structure (Analysis Framework)

FIGURE 5-12 Risk Breakdown Structure (Identified Risks)

Various techniques for qualitative risk analysis exist. One method involves using the WBS as the framework and estimating the risk probability of selected elements, as well as estimating the impact on the project of the same elements should the risk come to pass. The products of these two factors are ranked to determine the higher-risk areas.

This semi-qualitative approach for assessing risk can be used for any type of project: simple or complex, small or large; it can also be used on a project for a product, a service, or a result.27 Leading the team through the process of identifying and quantifying the risks builds understanding of what the potential problems might be and agreement about how the team will respond.

OMB Circular A-1128 and the implementing directives from many U.S. government departments require that risk management plans be developed for government projects. For a complete discussion of risk management and more sophisticated techniques, see the DoD Risk Management Guide29 or the Defense Acquisition Deskbook, which can be found in the Acquisition Support Center (http://center.dau.mil). The recent book by Hillson and Simon30 is also useful. Note that all the techniques, regardless of their level of sophistication, use the WBS framework to assist in risk identification.

PROJECT INTEGRATION MANAGEMENT

Project integration management includes the processes required to ensure that the various elements of the project are properly coordinated. The WBS is an obvious tool that can assist in this task.

Two aspects of project integration management involve the WBS: the project plan and integrated change control.

Project Plan

The project plan is a document that is used to guide both project execution and project control. A WBS defined to the level at which management control will be exercised is included as a baseline document within the Project Plan. Figure 5-13 is sample outline for a project plan.

FIGURE 5-13 Sample Project Plan Outline

Based on the project plan, a work authorization system, using the WBS numbering scheme to reference the relevant work, is used to provide permission to proceed with specified project work.

Configuration Management

Configuration management is the process of managing the technical configuration of items being developed whose requirements are specified and of managing the scope of the project. Deliverable items are designated in the WBS, the schedule, and the SOW, or in other project documents.

Configuration management involves defining the deliverable items and setting a baseline, controlling the changes to that baseline, and accounting for all approved changes. In establishing the requirement for configuration management on a project, the project manager needs to designate which deliverables are subject to configuration management controls and the documents that formally describe the identified deliverables. When working to a contract, usually all deliverables are controlled. A contract deliverable designated for configuration management is called a “configuration item.” For software, this item is commonly called a computer software configuration item (CSCI).

In addition to deliverables, the contract SOW and the WBS become subject to configuration management in order to control changes that are proposed that will impact them. The WBS and WBS dictionary, the scope statement, and/or SOWs are the documents that define the scope of the project. When the WBS is defined, and when the project team and customer or sponsor agree that it is complete, it becomes part of the total baseline for the project. Work not covered by the WBS is not part of the project.

To add work to the project is to change scope. The project should use a formal process of change management for modifying the WBS and supporting documents by adding or deleting work in the SOW and changing project schedules and budgets accordingly. The WBS then becomes a major tool for controlling the phenomenon known as “scope creep.” Scope creep arises from unfunded, informal additions to the project work. Controlling scope creep is one of the project manager’s major tasks, and he or she has to start working on it even before the project SOW is written by making sure the processes are in place to establish an effective WBS, to clearly define the scope, and to establish control baselines.

When a request for a change is received, either formally or informally, a first step in the analysis is to determine whether the change affects the scope of the project. If the work to be performed is covered by the WBS and described in the WBS dictionary or the SOW, then it is in scope. Otherwise, the work is out of scope. In the latter case, the project manager needs to formally evaluate the impact of the change on cost, schedule, and technical performance, and then make the necessary changes to contractual documents and plans in order to implement the change, if it is approved.

Systems Engineering

All technical programs should implement a sound systems engineering process. Such a process is a comprehensive, iterative, and recursive problem-solving process that is applied sequentially and in a top-down fashion by integrated teams. The process transforms needs and requirements into a set of system product and process descriptions, generates information for decision makers, and provides input for the next level of development.

The process is applied sequentially, one level at a time, adding additional detail and definition with each level of development. The process is complex and includes inputs and outputs, requirements analysis, functional analysis and allocation, a requirements loop, synthesis, a design loop, verification, and system analysis and control. Inputs include customer requirements, and outputs include system and product specifications, configuration baselines, end-item definitions, and, of course, the WBS.

The systems engineering process is an iterative process that starts early in the life cycle and continues throughout the program. Most government agencies and private-sector organizations involved in systems development follow standard systems engineering methodologies.

NOTES

1. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 3rd ed. (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2004), 9–10.

2. Gregory T. Haugan, Project Management Fundamentals: Key Concepts and Methodology (Vienna, VA: Management Concepts, 2006).

3. Lewis Carroll, The Complete Works of Lewis Carroll (New York: The Modern Library, Random House, 1922).

4. Peter S. Cole, How to Write a Statement of Work, 5th ed. (Vienna, VA: Man agement Concepts, 2003), 149.

5. Department of Defense, Handbook for Preparation of Statement of Work, MIL-HDBK-245D (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 1996).

6. Paul W. Hewitt, “International Infrastructure Project, Cost Estimating WBS,” Construction International, Copybook Solutions LTD. Online at http://www.construction-int.com (accessed February 2008).

7. Department of Defense, DoD Handbook: Work Breakdown Structures, MIL-HDBK-881A, Section 1.4.3, “Challenges” (Washington, D.C.: Department of De fense, 2005).

8. American National Standards Institute, The ANSI/EIA-748-A Standard for Earned Value Management Systems (Washington, D.C.: American National Standards Institute, 1998), 15.

9. Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-11: Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget, Part 7, Section 300, “Planning, Budgeting, Acquisition, and Management of Capital Assets” (Washington, D.C.: Office of Management and Budget, 2002), 5.

10. National Defense Industrial Association, Project Management Systems Committee, Earned Value Management Systems Intent Guide (Arlington, VA: National Defense Industrial Association, November 2006), A-2.

11. Defense Contract Management Agency, Earned Value Management Implementation Guide, October 2006. Online at http://www.acq.osd.mil/pm (accessed February 2008).

12. Defense Contract Management Agency, Earned Value Implementation Guide, Section 2.2.5.2.

13. For more information, see the Defense Cost and Resource Center website, “Defense Cost and Resource Center – Enhancing DoD Cost Analysis.” Online at http://dcarc.pae.osd.mil/ (accessed February 2008).

14. Humphreys & Associates, Pocket Guide to Program Management Using an Earned Value Management System (Orange, CA: Humphreys & Associates, 2002), 63.

15. Department of Defense, Industry Integrated Baseline Review Integrated Product Team, Program Managers Guide to the Review of an Integrated Baseline (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2001).

16. Haugan, Project Management Fundamentals, 157.

17. Department of Defense, Department of Defense Handbook for Preparation of Statement of Work (SOW), 25–28.

18. Ibid., 27.

19. Cole, How to Write a Statement of Work, 5th ed.

20. R. Marshall Engelbeck, Acquisition Management (Vienna, VA: Management Concepts, 2002).

21. John P. Kotter, Leading Change (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996).

22. See also Department of Defense, Defense Systems Management College, DSMC Program Managers Tool Kit, 10th ed. (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2001), 46.

23. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), 3rd ed., 237.

24. Adapted from Department of Defense, Defense Acquisition Deskbook, Section 2.5.2 (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2004).

25. Defense Acquisition University, Risk Management Guide for DoD Acquisition, 4th ed. (Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Acquisition University Press, February 2001).

26. David Hillson and Peter Simon, Practical Project Risk Management: The ATOM Methodology (Vienna, VA: Management Concepts, 2007), 51.

27. This process is described in more detail in Haugan, Project Management Fundamentals, 229.

28. Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-11: Preparation, Submission, and Execution of the Budget (Washington, D.C.: Office of Management and Budget, 2002).

29. See note 25 above.

30. Hillson and Simon, Practical Project Risk Management, 20–21.