CHAPTER 9

The WBS in Construction Management

Analogous to other industries and the government, construction management has its own language and mystique, and has been using WBSs for many years but not in quite the same manner as discussed in this book. The construction industry worldwide has been using construction breakdowns to assist in project cost estimation and to report progress and costs for payment purposes. However, they have not been generally used to define scope or provide a basis for schedule planning. This chapter discusses these construction breakdown systems and their relevance to the WBS and project management, and how to adapt them to the broader project management support roles.

CONSTRUCTION CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

The construction industry has developed its systems and practices in parallel to the DoD-based project management systems discussed up to this point. While the construction industry now plans and implements projects using PMBOK® Guide methodology, classification systems for construction work exist and are widely used for other purposes. This section discusses the major classification systems and their uses.

Background

The concept of a WBS has existed for 50 years, as discussed in Chapter 1. In 1968, the DoD developed a standard for the top-level decomposition of WBSs for DoD systems. That standard was made mandatory for use on all defense projects that were estimated to exceed $10 million in research, development, test, and engineering (RDT&E) funds. A single, generic WBS was not proposed, but the new standard evolved into a set of eight WBS templates and related WBS dictionaries by 2005. Figure 8-1 in the previous chapter shows one of these templates.

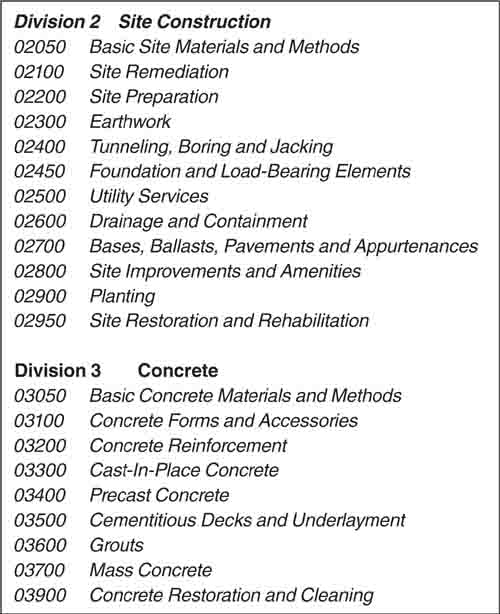

Classification systems for construction, which are closely related to the WBS, have existed for at least 40 years. Their purpose is to provide an indexing system for organizing construction data, particularly construction specifications, and to facilitate communications between various organizations and databases. They are also used to collect data in a common framework to facilitate cost estimating and reporting activities. Figure 9-1 shows part of one of these frameworks: a Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) work breakdown system.1 (The complete breakdown is included in Appendix B.) It is not called a WBS because the breakdown in each division is a list of categories and does not follow the 100 percent rule as previously defined. The listings are used to categorize items other than work. However—and this is important—these categories, whether the division or item within the division, try to follow their own 100 percent rule: The listings of items within each division (or subdivision) represent 100 percent of the types of construction within each parent category. Each of the individual items listed in Figure 9-1 has a further listing of subcategories, as is discussed and shown later.

FIGURE 9-1 Sample CSI MasterFormat™ Division Structure

The term WBS has become a common term in all fields related to cost engineering, including construction cost estimating, scheduling, and project cost control. A well-defined WBS is the backbone of good construction estimating software and can take several forms, including the breakdown of items within an estimate, the layout of groups within a schedule, or the roll-up of accounts within a cost report. A WBS usually starts with a client’s desire to break down a tender into definable pay items, followed by the project manager’s wish to schedule activities of work in a logical and efficient manner and the contract cost control engineer’s goal to track and forecast costs and build a historical database for future estimation purposes. In each case, a properly organized WBS is required.2

The construction standard division breakdowns were not originally planned for use as a WBS, as we know it and as has been the focus of this book. However, with only minor exceptions, the classification systems that have been developed are an excellent starting point for developing a WBS for a construction project and for development of a tool to be used to collect comparable data across projects. The standard division breakdowns have the same goals as the DoD WBS templates. They are also very useful as a WBS template from which to choose the appropriate work elements when planning a project. From an enterprise perspective, the numbering system can be retained, and data that are collected from various projects can then be compared or compiled as a reference database.

The situation that the international construction industry faces today is that there has been no common work breakdown upon which to communicate and transfer data between project participants.3 Traditional agencies such as state and other governmental highway authorities have all developed their own tender breakdowns, many of which existed long before the creation of electronic data transfer. Construction estimators have tended to follow the layout of the bids as provided by the government agencies. The scheduler commonly ignores the customary estimate breakdown because it does not logically adapt well to the sequence of work activities. The cost control engineer has to roll up the project costs into a corporate chart of accounts that creates even more inconsistency.

Many standard project WBSs have been created over the years. The CSI (Construction Specifications Institute) format in North America and the SMM7 (Standard Method of Measurement) format in Great Britain are the most common and have been in existence since the early 1960s. These WBSs originated as breakdowns for commercial building construction and quantity survey, but both have evolved over the years to include other forms of construction. The CSI (Construction Specifications Institute), which publishes the most popular work breakdown in North America, introduced an expanded version of its MasterFormat™ in 2004.4 The work breakdown now includes 50 divisions of work covering civil site work as well as process equipment, a significant increase over the previous 16 divisions of work that had been in use for years.

Other organizations in the construction business, such as the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), have developed a standard WBS for highway construction projects, and work is proceeding in the areas of building information modeling (BIM), which uses a hierarchical structure of work elements that in effect is a WBS.

The following sections briefly describe some of the current construction classification systems and relevant concepts and constructs.

Construction Specifications Institute, CSI Masterformat™

The Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) is an organization that “maintains and advances the standardization of construction language as pertains to building specifications.”5 CSI provides structured guidelines for specification writing in its Project Resource Manual, formerly called the Manual of Practice (MOP), and provides several other documents, such as CSI MasterFormat™, described later. CSI has a building life cycle that guides practitioners through project conception, project delivery, project design, construction documentation, procurement bidding negotiations, construction, and facility management.6

CSI is a national association dedicated to creating standards and formats to improve construction documents and project delivery. The organization is unique in the construction industry in that its members are a cross section of people who provide various specifications: architects, engineers, contractors, and building materials suppliers. The organization has 146 chapters and more than 15,000 members. Monthly chapter meetings allow members the opportunity to communicate openly with their counterparts and peers in the construction industry and to exchange information for successful project management. CSI has a rigorous certification program for professionals seeking to improve their knowledge of accurate and concise construction documents.

CSI authored MasterFormat™, which is an indexing system for organizing construction data, particularly construction specifications. Since 1995, MasterFormat™ has consisted of 16 divisions of construction, such as Masonry, Electrical, Finishes, or Mechanical. These are presented in Appendix B. In November 2004, MasterFormat™ was expanded to 34 divisions, reflecting the growing complexity of the construction industry as well as the need to incorporate facility life cycle and maintenance information into the building knowledge base. Another level of detail was also added. One of the goals was to eventually help develop building information modeling so that it contained project specifications. See Appendix E for a listing of these divisions as incorporated in the OmniClass™ structures, which are described in the next section.

The MasterFormat™ standard serves as the organizational structure for construction industry publications such as the Sweets catalog, which provides a wide range of building products, and MasterSpec, a popular specification software. MasterFormat™ helps architects, engineers, owners, contractors, and manufacturers classify how various products are typically used. Nearly all CSI-approved sections also include performance and safety requirements generated by agencies such as the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and numerous other federal government and professional organizations.

MasterFormat™ was initially based on a concept that paralleled “work results,” a term that was not in common usage until recently. Over the last 40 years, MasterFormat™ gradually changed from a listing of specification section titles (mostly work results) into a less-disciplined combined listing of work results, products, and materials. The 2004 edition of MasterFormat™ was designed to bring the document back to its roots as a listing of work results, with significant changes in its organization, titles, and numbers.

OmniClass™ Construction Classification System7

The OmniClass™ Construction Classification System (known as OmniClass™ or OCCS) is a new classification system for the construction industry. It is useful for many additional applications—organizing library materials, product literature, and project information, and providing a classification structure for electronic databases. It incorporates other extant systems currently in use as the basis of many of its tables: MasterFormat™ for work results, UniFormat for elements, and EPIC (Electronic Product Information Cooperation) for structuring products.

OmniClass™ is characterized by its developers as a strategy for classifying the entire built environment. It is designed to provide a standardized basis for classifying information created and used by the North American architectural, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry—throughout the full facility life cycle from conception to demolition or reuse. Omni-Class™ is intended to encompass all the different types of construction that make up the built environment and to be the means for organizing, sorting, and retrieving information, as well as deriving relational computer applications.

OmniClass™ is also used for organizing many different forms of information, electronic and hard copy, in libraries and archives, and for use in preparing project information, communication exchange information, cost information, specification information, and other information that is generated during respective project processes.

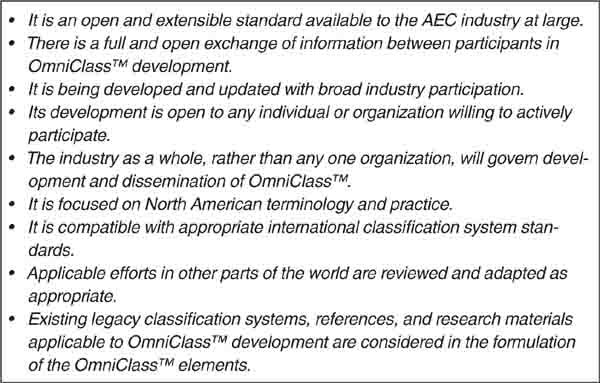

OmniClass™ follows the international framework set out in International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Technical Report 14177, Classification of information in the construction industry, July 1994. That document was later established as a standard in ISO 12006-2: Organization of Information about Construction Works—Part 2: Framework for Classification of Information. OmniClass™ has been developed under the auspices of the guiding principles established by the OCCS Development Committee at its September 29, 2000, inaugural meeting and listed in Figure 9-2:

FIGURE 9-2 OmniClass™ Building Principles

The organization and membership of the OmniClass™ Development Committee are presented in Appendix C. This appendix is included to illustrate the strong industry support for this activity. Appendixes D–F are provided to further explain the detail available within OmniClass™ and to support the discussions of OmniClass™ later in this section.

OmniClass™ consists of 15 tables, each of which represents a different facet of construction information. Each table can be used independently to classify a particular type of information, or entries on it can be combined with entries on other tables to classify more complex subjects. The tables are not numbered sequentially, and there are gaps in the progression. The first table is Table 11—Construction Entities by Function and the last of the 15 tables is Table 49—Properties.

The OmniClass™ structures are conceptually similar to the DoD WBS template model at the system level, as discussed in the previous chapter. Table 21, under “Utilities and Infrastructure,” includes breakdowns for Roadways, Railways, Airports, Space Travel, Utilities, and Water-Related Construction. This breakdown is not unlike—in concept—aircraft systems, electronic systems, missile systems, ship systems, and so on, from the DoD template.

Appendix C provides more information on the OmniClass™ Development Committee, and Appendix D describes the OmniClass™ tables and their contents.

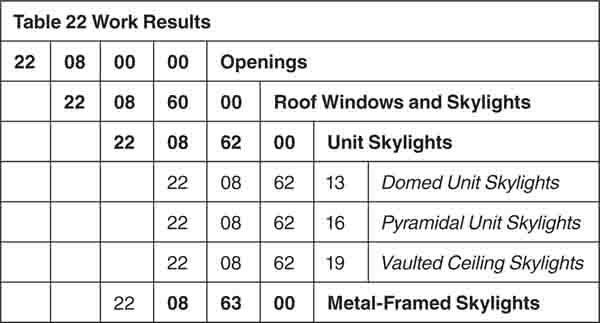

OmniClass™ Table 22 is the table that is most relevant to our purposes. It is based almost entirely on the MasterFormat™ tables discussed earlier, although it is noted in OmniClass™ that “…some content of MasterFormat™ 2004 Edition is not included in Table 22.”8

None of the current breakdowns, including CSI, fully cover the complete civil infrastructure project life cycle, including development, engineering, construction, operations, maintenance, and risk mitigation. The CSI MasterFormat™ 2004 Edition comes closest to covering all the scope of work found in the construction of building facilities and site work. It falls short in addressing the unique requirements of program managers, estimators, schedulers, and cost engineers in identifying all phases of work included in major Infrastructure work such as Build Own and Transfer (BOT) programs.

Relation to a Project WBS

These structures, MasterFormat™ and OmniClass™, are not WBSs, although some subsections have the appearance of a WBS. However, at all levels, the elements in the structures are candidates for WBS element descriptors, including work packages, and they are all nouns or nouns and adjectives, meeting our definition of WBS elements.

There are many listings available in MasterFormat™ that would enable an organization to pick and choose to provide ready-to-go WBS elements for virtually any work on any construction project, including related equipment and furnishings. It must be noted again, however, that the summary headings are not truly WBS elements, because the breakdown or listings under the headings are further listings of categories within the heading and do not meet the WBS 100 percent rule, nor are they project-specific. Figure 9-3 shows the breakdown of Unit Skylights in Table 22 of OmniClass™ and illustrates the three categories of Unit Skylights. In a given building it is likely that only one type would be used.

FIGURE 9-3 OmniClass™ Table 229

The breakdown under Unit Skylights contains all the different types of unit skylights. The project would be expected to use only one of these types for a given building, if it had a unit skylight at all.

HIGHWAY CONSTRUCTION—CALTRANS

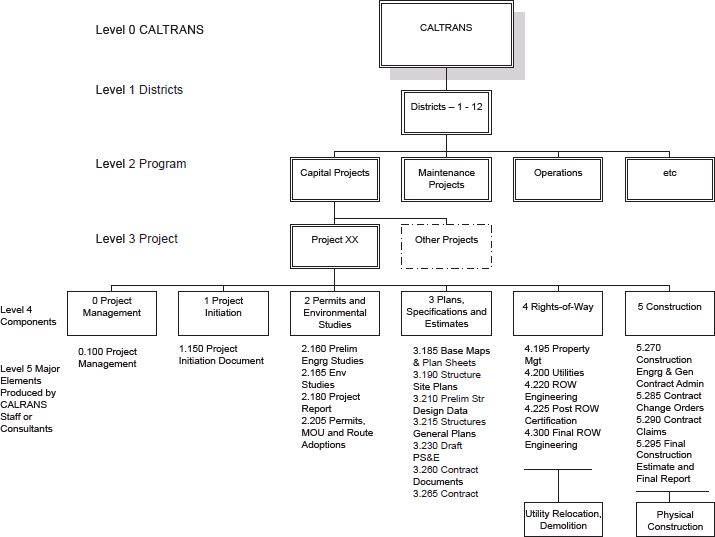

The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) has a standard WBS that must be used in its transportation construction projects. The work of Caltrans is to manage the construction projects and not to perform the construction work itself. Therefore, its standard WBS was developed to address the work performed by Caltrans. The contractors are expected to plan their own work on each project. This distinction is an important one.

Caltrans WBS Development10

In the early 1990s, several task forces and special reviews recommended that Caltrans establish a modern project management process and develop the tools to help improve its project delivery. Caltrans issued the first version of the Capital Outlay Support (COS) Standard Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) in July 1994. Subsequent updates to the standard have been published frequently, with a version published in August 2006 (WBS Release 8.0B). Again, to repeat, this WBS is for only the work performed in-house by Caltrans in the planning, organizing, and managing of construction projects. Caltrans also uses this breakdown for collecting hours worked and similar costs. The WBS for the actual construction work is the responsibility of the contractor, which would likely use the MasterFormat™ work breakdown.

The Caltrans WBS and the defined Standard Cost Centers and Milestones provide a complete foundation for planning and controlling project work content, cost, schedules, and quality. The WBS and all related documents and guidance are available at http://www.dot.ca.gov.

Purpose of the Caltrans Standard and Guide

The purpose of the Caltrans Guide is to provide a statewide standard. It contains information regarding the Project Delivery Workplan Standards and use of these standards to plan and control the work content of capital projects.

The document also presents guidelines for preparing, understanding, and presenting a WBS for a given capital project. Caltrans uses two distinct forms of WBSs: Project WBS (PWBS), which is used for individual projects and employs only work elements at a specified detail level, and the Standard WBS (SWBS), which contains all the standard work elements that could be required to complete a Caltrans capital project. These two types of WBSs are defined in more detail in the following paragraphs:11

Project Work Breakdown Structure (PWBS) – The PWBS defines the total scope of a particular project in a hierarchal format. Although it describes the same project scope as the corresponding scope statement, it is usually much more precise and detailed. It is the foundation of a project schedule and project resource estimates, and is used to build the project workplan. The elements at the bottom of the hierarchy are called Work Packages (WPs). A WP is a “deliverable at the lowest level of the WBS.” Work Packages may be divided into activities. Thus, the work contents of the project can be viewed as the set of WPs obtained by applying the WBS.

Standard Work Breakdown Structure (SWBS) – The SWBS contains all the work elements, descriptions, and identifiers that a Caltrans capital project can contain. No PWBS is likely to contain all of the SWBS work elements. The SWBS contains only work and is completely independent of schedule, milestones, sequence, precedence, cost, resources, quality, and anything else except the work definition and “identifier.” It is used to standardize the work elements and breakdown structure used in capital projects throughout the state so that computers can analyze project data.

According to Caltrans, a standard WBS has many benefits, including:

![]() Consistency of information needed to manage a statewide workforce

Consistency of information needed to manage a statewide workforce

![]() More effective communication relative to project-level work throughout the department

More effective communication relative to project-level work throughout the department

![]() Ease of data transfer, such as the sharing of project “templates” between and within districts

Ease of data transfer, such as the sharing of project “templates” between and within districts

![]() Decreased “culture shock” when employees transfer to different locations and work assignments

Decreased “culture shock” when employees transfer to different locations and work assignments

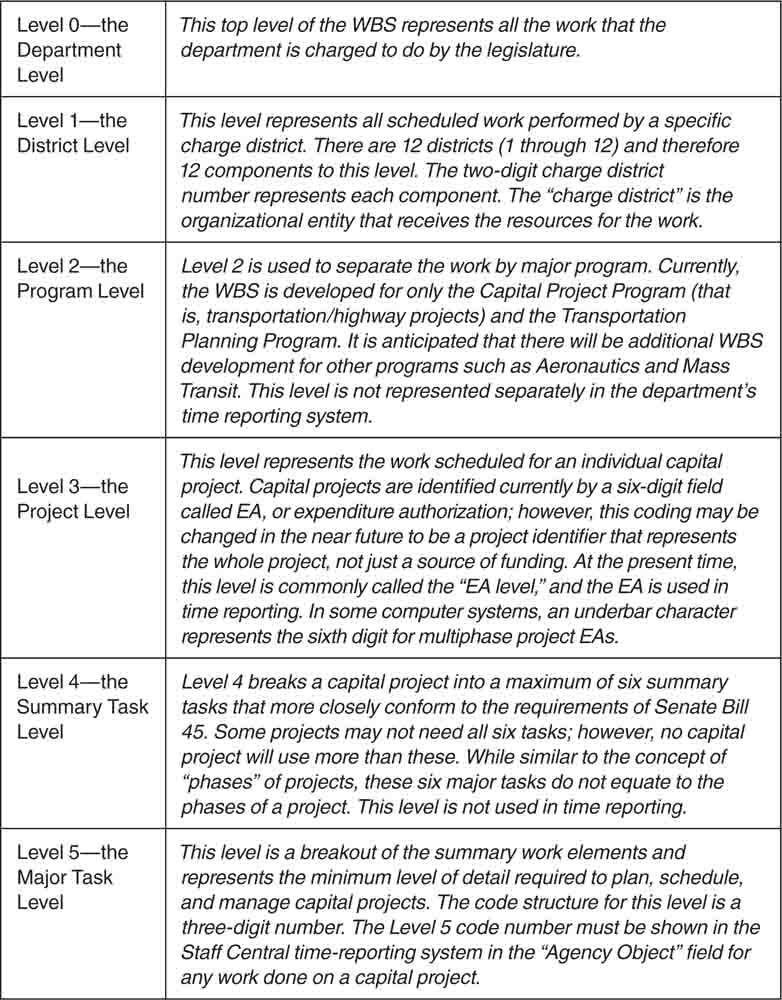

Standard Template—Levels of the WBS

To facilitate summary reporting of work done, the WBS contains several levels of breakdown of the work, starting with Level 0. Each succeeding level breaks down the work into component parts. Each level represents a summary of the work below it and can be the basis for reporting that gets as detailed as needed.

A graphic representation of the WBS Levels 0 through 5 is shown in Figure 9-4 and may be helpful to summarize the following discussion about levels.

FIGURE 9-4 Caltrans WBS Hierarchy

Figure 9-5 contains a description of each level identified in Figure 9-4.

FIGURE 9-5 Caltrans WBS LEVELS12

The WBS for California capital projects has been standardized to this level of detail for statewide reporting purposes at this time. There is no standardization lower than Level 7 for most work packages, and Level 8 for a few work packages. However, further breakdowns may be used if needed and may be standardized at some future date.

A complete listing of WBS work elements for Levels 5, 6, 7, and 8 is provided in Appendix D of the Caltrans Guide.

A sample page from the Caltrans Guide is presented in Appendix G. The reader should be aware of two factors: (1) The work represented is that done by Caltrans and/or consultants in support of the project in their role as construction manager, and no physical construction activities are performed by Caltrans; and (2) this represents a complete list of possible WBS elements; not all are used or needed on a particular project. However, the WBS definitions and basic coding are the same as those in the Guide, although the prefix may change, as shown in Figure 9-1.

WHAT WOULD A GENERIC, UNIVERSAL CONSTRUCTION WBS TEMPLATE LOOK LIKE?

The conclusion to be drawn from the preceding sections is that there has been a lot of effort put into classifying and organizing the work performed in construction projects and that these efforts can be used to develop a WBS template for the management of construction programs and projects. Four requirements need to be met:

1. A generic top-level program WBS for the enterprise that includes all the different types of programs

2. One or more specific projects that are identified with a program

3. A complete list of possible WBS elements in hierarchical form that would apply to each project

4. A set of rules or criteria to integrate items 1, 2, and 3

The second item is needed because the WBS must be based on a specific construction configuration. For example, is it one tower or does it consist of two or three towers that are interconnected? That is, are there separate structures to be constructed as part of the project? The physical layout interacts with the standard terminology.

Note that we are not proposing a standard WBS per se; we are, however, proposing that a standard WBS framework and a standard set of WBS elements be used. In such a framework, the lower-level elements can be selected to form a WBS that is tailored to the specific project design and construction methods.

A “Standard Work Breakdown Template” would format the project into a multilevel WBS suited to plan, estimate, and schedule as well as track costs and measure performance on construction projects. The breakdown is also designed to facilitate the data transfer of a standard work breakdown between common estimating, scheduling, and cost-control software applications.

Appendix H presents a recommended “Standard Work Breakdown Structure” for international infrastructure projects, as proposed by Paul Hewitt, the Principal of International Project Estimating, Ltd. Hewitt makes three recommendations that differ significantly from the existing CSI MasterFormat™ and OmniClass™ structures:13

1. He recognizes the need for a WBS element comparable to “Project Management” to address the costs and resources involved in this element.

2. He recognizes the need for life cycle program planning and addressing the specific WBS elements involved in phases such as Closeout and Operations and Maintenance.

3. He recognizes that standard WBSs are needed for construction programs such as Dams, Railways, Airfields, and so on.

These three concepts are not specifically addressed in the MasterFormat™ and OmniClass™ structures. The common constructs that are addressed are for building construction only, which of course is the most prevalent.

USE OF A WBS TEMPLATE—A CASE STUDY

As previously explained, there has been a lot of effort put forth by the U.S. government into creating templates for hierarchical structures in order to provide frameworks for planning and management. Using these concepts, a recommended WBS Program Template for GSA has been developed as a method of presenting the concepts discussed in this chapter.14

The basic concept in developing this template is to start with the normal WBS hierarchical structure from the top down and take into consideration the actual structure of the building. Then use the lowest levels of Master-Format™ to describe the lowest levels of the WBS—the work packages in the template. This includes the MasterFormat™ element numbers and titles.

The author performed an analysis of the very large WBS developed for the construction of a new Department of Transportation headquarters building which verified that this approach was feasible and would be compatible with current MasterFormat™ elements. The recommended template is more complex than the system templates used by the DoD and addressed in MIL-HDBK-881A because the programs are more varied.

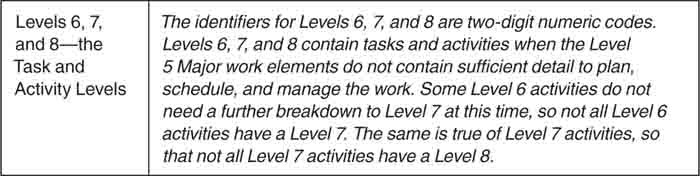

GSA Enterprise WBS

Figure 9-6 presents an enterprise WBS prepared for this case study using part of the GSA organization structure. Levels 0 through 3 can be considered Executive Levels, and Level 4 is where the Program WBSs begin. Level 5 is the current GSA Life Cycle Program structure in WBS format. It consists of six phases and the cross-cutting element “Program Management.” A possible Level 6 breakdown of Program Management is shown for reference.

The Program Management element represents the top-level management of the six phases of the total life cycle and could be a PMO that exists throughout the entire life cycle.

Each one of the other six phases would be considered a “Project” and have a standard WBS with the Level 5 element at the top.

WBS Elements

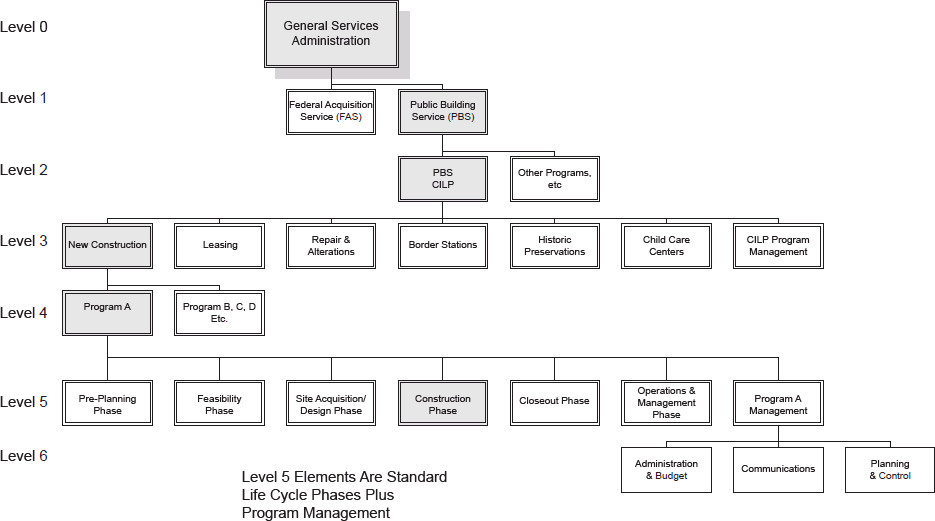

For years, the construction industry has been using a standard structure or framework for organizing information about construction projects, as was discussed previously in this chapter. These structures provide the basis for a project WBS.

Appendix B describes the 1995 CSI Structure for the Construction Phase. These 16 Divisions plus the Division 0, renamed Project Management (not Program Management), with some additional elements added, would serve as a workable list of WBS elements similar in concept to the Caltrans set of WBS elements.

This set of WBS elements, in organization chart format, would look like Figure 9-7.

FIGURE 9-7 CSI Construction Phase Divisions (1995)

The CSI structure does not have a “Project Management” category as such because it is not designed as a WBS but is a breakdown of direct work. “Project Management” tends to be an indirect or overhead type of activity. Construction projects use a category called “General Conditions” to account for project management-type costs. So a standard WBS would need a standard breakdown for the Project Management work such as the Program Management element in Figure 9-5.

A basic assumption in this WBS element structure is that the 100 percent rule is followed—that the sum of the work elements at Level 2 represented by the child elements at Level 3 is 100 percent of the work elements represented by the parent. In the case of Figure 9-7, the 100 percent rule requires that the 17 elements are a complete set—that all the work in the Construction Phase is covered by the 17 elements. For every element of construction and every work package in an actual project, there would be a category that named that work package. Every activity in the project would logically fit within one of those elements.

However, this does not mean that every one of these elements is represented in every project, or even in any specific project. In Figure 9-3, for example, three different types of unit skylights are presented. In other words, the assumption is that there are only three types of unit skylights. There is no requirement that a given building must have a unit skylight, or a metal skylight, or even a skylight—only that there is a category within the framework to identify the type of skylight that would translate into a skylight work package in the WBS.

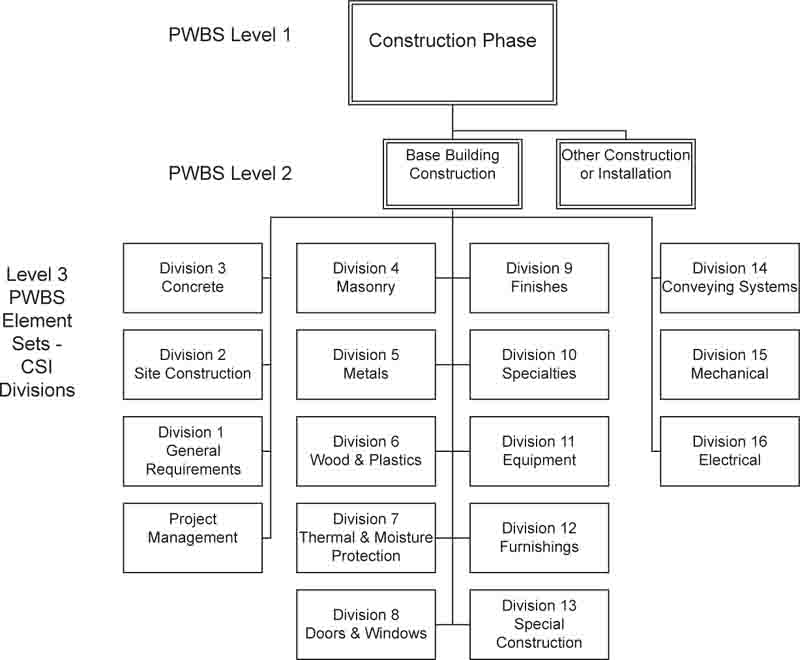

APPLICATION TO AN EXISTING PROGRAM—A CASE STUDY

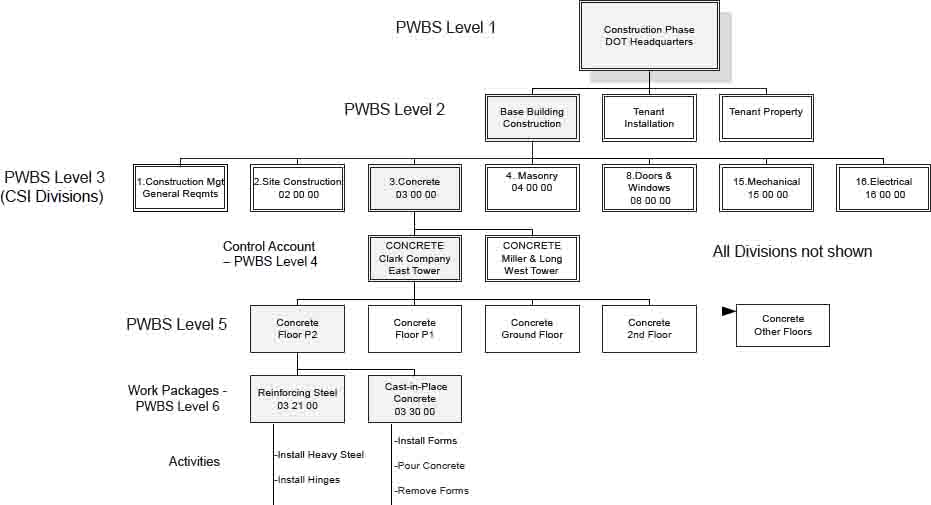

Figure 9-8 shows the application of the CSI/WBS template to a real project. The Project WBS needs to match the way the building is to be constructed, and the template elements need to be integrated into this structure. For example, the WBS for Concrete Work in the East Tower of the New DOT Headquarters Building Program would be as shown in Figure 9-8.

FIGURE 9-8 Construction Project WBS

For a project, the upper levels of the WBS must be structured to match the physical design of the building, as shown in Figure 9-8. The shaded boxes are the WBS elements that match the Standard Template or CSI structure. The Control Account level identifies the specific contractor responsible for the work in the breakdown below it. It is possible that the Control Account could be at Level 3 if one contractor were responsible for all Mechanical items (Division 15) or all Electrical items (Division 16). In fact, this was the situation in the New DOT Headquarters Building. This is the same Control Account as would exist in an EVMS.

The lowest level of the WBS is the work package. The work packages are the descriptors from the CSI structure. The schedule activities are identified down to each work package in the figure.

As the planning and work proceed and as the subcontractors are determined, the organizations, contractors, or subcontractors would be identified down to the specific WBS element and be expected to use the standard breakdown for work scheduling and for the Table of Values for submitting bills for payment.15

In the beginning stages of the project, the general contractor and all the subcontractors are not yet identified, and the WBS would be organized around the CSI categories, with the appropriate subcategories tailored to the specific design or requirements.

The Standard WBS would be converted to a Project WBS as responsibilities are identified and as contracts and subcontracts are identified.

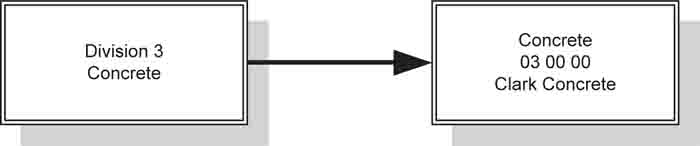

For example, Figure 9-9 shows that Division 3 Concrete would be converted to Clark Concrete Company at the same level or split into two WBS elements if there were two major subcontracts.

FIGURE 9-9 Conversion from Template to Operational WBS

The name of the contractor to perform the concrete work and the WBS number would be added. If there were more than one concrete contractor, such as one for the West Building and one for the East Building, similar work breakdowns with the appropriate contractor names would be used.

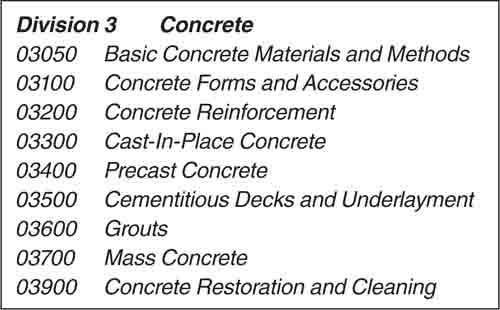

The WBS is then developed further, for example, as shown in Figure 9-8, the P2 (parking) and other levels of the building are identified, and the work to be performed in each work package is the appropriate next level breakdown item in the CSI Division structure. The next level under “concrete” would be one of the items from Figure 9-10; in this case, 03300, Cast-in-Place Concrete.16

FIGURE 9-10 CSI WBS for Concrete

So one work package at Level 6 would be Clark Concrete, P-2 Level, 03210 Reinforcing Steel, and the other work package would be Clark Concrete, P-2 Level, 03300 Cast-in-Place Concrete. The various activities shown on the schedule would be the activities and their resources included in the schedule, Primavera©, in this example.

In conclusion, the WBS template for construction is different from the WBS template used by the DoD for major systems. The DoD approach is to have common upper three levels for each system, with work packages tailored to the project at much lower levels. The construction industry approach would be to have a standard nomenclature for work packages at the detailed level within a looser upper-level framework consisting of cost accounts.

Hewitt has proposed considering a WBS template that would have some comparability to the DoD approach by having separate templates for Walls, Bridges, Tunnels, Rail, Airfields, Marine Facilities, Dams, and the like. (See Appendix H.)

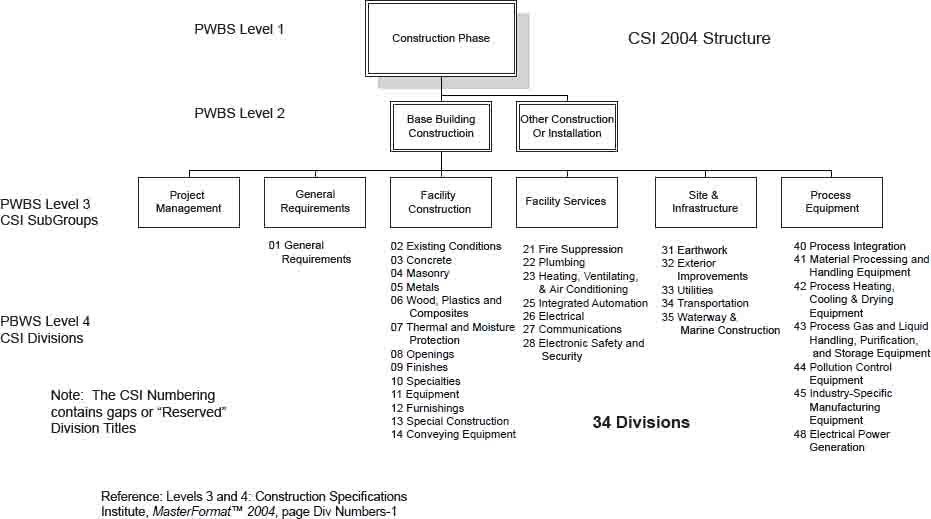

CSI MasterFormat™ 2004 Structure

The preceding section was based on the CSI MasterFormat™ 1995 structure. Figure 9-11 is the same structure shown in Figure 9-8, but it has been updated using the CSI MasterFormat™ 2004 structure.

FIGURE 9-11 CSI Construction Phase Divisions (2004)

There are two major differences between the 1995 version and the 2004 update: (1) There are 34 instead of 16 Divisions, and (2) the Divisions have been segregated into five “Subgroups.”17 The potential user of the structure in a WBS will have to determine which is more applicable. The advantage of the 1995 set of divisions is that it is smaller, but as long as the divisions represent 100 percent of the work there is no problem. The advantage of the 2004 set of divisions is that it is easier to identify the specific work element and provide a more detailed structure. Also, the industry tends to follow the CSI structure, as does OmniClass™ for the international structures, so the 1995 approach should be considered obsolete.

NOTES

1. Division codes are reprinted with permission from Construction Notebook News,CSI MasterFormat™ Division List. Online at http://www.constructionnotebook.com/ipin2/CSIDivisions.asp (accessed April 16, 2008).

2. Paul W. Hewitt, “International Infrastructure Project, Cost Estimating WBS,” Construction International, Copybook Solutions LTD. Online at http://www.construction-int.com (accessed February 2008).

3. Ibid.

4. The Construction Specifications Institute, “MasterFormat™ 2004 Edition.” Online at http://www.csinet.org (accessed February 2008).

5. The Construction Specifications Institute, “About CSI: Standards and Formats, Professional Development and Certification.” Online at http://www.csinet.org (accessed February 2008).

6. Ibid.

7. The data in this section and in Appendixes C–F are derived from material on the OmniClass™ webpage at http://www.omniclass.ca (ed. 1.0, 2006-03-28 release). Derived with permission. Copyright © 2006 the Secretariat for the OCCS Development Committee. All rights reserved. http://www.omniclass.org.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. California Department of Transportation, Caltrans Project Management Guidance. Online at http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/projmgmt/guidance.htm (accessed April 16, 2008).

11. California Department of Transportation, Caltrans Guide to Project Delivery Workplan Standards, Release 8.0 B, August 2006, 4. Online at http://www.dot.ca.gov/hq/projmgmt/guidance.htm (accessed May 29, 2008).

12. Ibid., 7–8.

13. See note 2 above.

14. This is a hypothetical case only; it has not been reviewed or approved by GSA. The example uses publicly available data to demonstrate the concepts.

15. For the Table of Values formats, see American Institute of Architects, 15. Application and Certificate for Payment, AIA Document G702 (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects, 1983).

16. See note 1 above.

17. Note that CSI and others refer to 50 Divisions in the 2004 edition. Actually, there are 16 unused numbers in the list, which are presumably reserved for future expansion.