Chapter 4

Budgeting

Here are some key factors to consider when pricing a design job:

• Scope of Work

What exactly are we doing? What services are we providing? What are the deliverables? In what format?

• Resources

Who will do the work? Do we have to supplement our team with additional designers? With what skills? How much do they cost? Do we need our senior or junior designers to do the work?

• Scheduling

How much time do we have? How much time do we need? How much time does each team member need? Do we need to juggle several projects simultaneously? How does that affect us?

• The Client

Have we worked for this client before? Are they decisive or prone to revisions? Are there layers of management that must be appeased or is there one decision maker? How available is that person?

• Collaborators

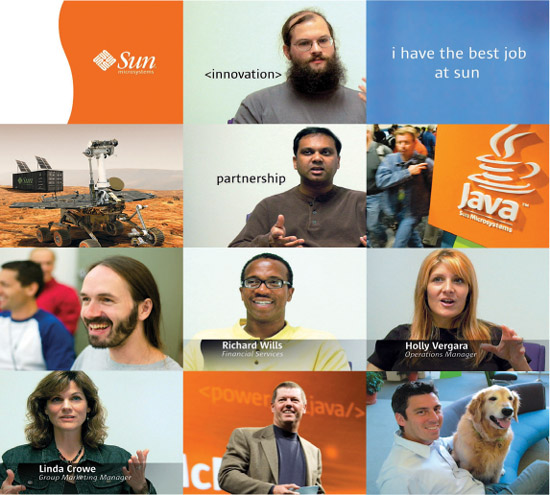

Beyond designers, who else needs to work on this project? What will they do? What will it cost? How much will be provided directly by the client?

• Quality

What are the client’s expectations? Are they willing to pay for it? Have we done something like this before? Will there be a lot of research, or can we immediately get to work?

• Expertise

Do we have it? How steep is the learning curve if we don’t? How will we know when we have a great design for this client?

• Cash Flow

What other jobs are in-house right now? How much money do we need? Design is a business, and all businesses have real financial requirements and obligations. What are ours?

The answers to these questions have cost implications. The more experienced a design manager is at answering and anticipating these tough questions and the better his or her documented records are on previous projects, the more accurate the design manager will be in pricing and budgeting projects.

Determine Your Rate

You can determine an hourly rate for design services in several ways. Many design organizations worldwide have published this kind of information as a reference. For example, in the United States, the AIGA publishes an annual wage and salary survey. You can divide the average annual salary reported in the survey by the number of billable hours in a year (1,500 hours is a good round-number average to use). This calculation gives you an hourly rate based on the organization’s member submission information. A discussion with peers and colleagues may yield a ballpark idea of what they charge per hour. However, many people shy away from this kind of conversation and often don’t tell the truth. If they trust you, and don’t directly compete with you for client business, they may reveal this information.

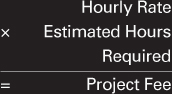

Calculation Based on Real Needs

Here is a formula for determining your hourly rate based on your actual costs of staying in business. It’s not the only way to determine an hourly rate, and it doesn’t factor in the value of the work to a client’s business or a premium for your expertise; it’s merely based on actual economic needs.

Reviewing Pricing

Designers must know their hourly rate to set their fee for particular design jobs—both the breakeven hourly rate to understand the lowest fee they should charge, and the published hourly rate to allow for profit and tax obligations (see page 95). Calculating a fee using both sets of rates shows you where the job must be priced (breakeven) and what is an optimum price (published hourly rate). However, it is hard to know exactly how many hours it will take to do any design project. Therefore, any estimate based on hours is just that: an educated guess on the duration and complexity of the work. As such, pricing jobs strictly on hourly rates is not a 100 percent accurate approach.

Evaluating Your Calculations

To get a more well-rounded view of pricing, review the project total you calculated using your published hourly rate and ask yourself the following questions:

Does this total reflect the value of this work to the client? Does it reflect the expertise we bring to the project?

Can we get more money for this job based on who the client is? In other words, is this client a small regional startup company or a well-funded multinational corporation? Little businesses typically have little budget, and big businesses should have a big budget. What have we charged for similar projects in the past? How is this project the same or different from those? Is that reflected in this price calculation?

What do we think our competitors would charge for this project? Why do we think that? Can we discuss our calculation with anyone?

(Talking about pricing design with a colleague or two is fine. Note, however, that in most countries, banding together as a profession and determining an industrywide price is illegal. It’s a form of collusion called price-fixing. This is why design organizations as a group rarely discuss in public or publish pricing information.)

Is there any published information on pricing for this type of work? For example, the Graphic Artist Guild’s Pricing and Ethical Guidelines publishes rate information. The organization polls its members, has them price certain kinds of projects, and then publishes that information. It can legally do this in the United States because it is a trade union, and it operates under different laws than nonprofit design (arts) organizations.

Does this price calculation seem high or low based on your gut instinct? How should it be adjusted?

Two design firms can have the same published hourly rate and calculate two different project fees using that rate. For example, one design firm may work slower or have more people involved; this means it estimates more hours into a project and it charges more. Only by keeping very good records, especially time sheets, on all projects and then comparing estimates to actual costs can designers price their work accurately over time.

A trusted client may be candid and tell the designer what competitors would charge on a particular job, particularly if the designer lost the job to a competitor. It’s important to learn why a design firm lost out on an opportunity, but remember that it isn’t always a question of money.

Another useful strategy is to develop relationships with other designers that can include discussions of money.

Remember that big fees don’t necessarily mean big profits. It all comes down to how the project is run. How long did the designer work on the project to earn that fee? Maybe we spent very little time on the project, but the work was tremendously valuable to the client’s business. These things are unique to every design project. It is why most designers are always wondering whether they charged enough on a job and whether they could have made more money.

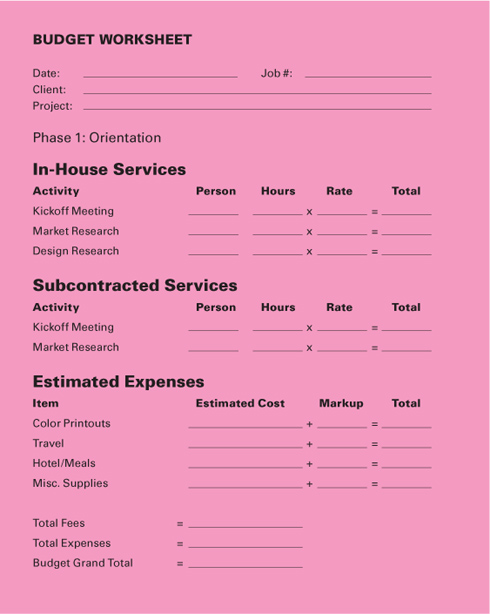

Breaking Down a Budget

When thinking about pricing a project, it’s logical to consider who will be doing the work. The members of a design firm are likely paid at different rates depending on experience and expertise. For example, a partner in the firm will typically have a higher rate than a junior designer. Therefore, in calculating a fee, consider what it costs the firm to do the work. If a junior designer is doing 75 percent of the work, the project can be priced lower. Alternatively, you can calculate the price by determining the average rate of all the designers in the firm. This is called a blended hourly rate or collective hourly rate.

Individual versus Collective or Blended Rates

Many design firms utilize their blended hourly rate when creating their published hourly rate. Often, they do this because in many projects, everyone on the staff is involved at some point, so rather than trying to determine the exact number of hours each person will spend on the project, the manager estimates the total number of hours the job will require. For some designers, this calculation is simply easier.

If the firm uses design project management software, it will be prompted to identify an hourly rate for an individual (presumably based on salary and benefit costs) and for particular tasks (e.g., strategy is more expensive than production of finished files). With these computer programs, it’s easy to look at project costs from several different angles, which is always a good practice in pricing graphic design.

Pricing versus Budgeting

Pricing a job is, in essence, estimating: getting an overall sense of the fees and expenses a design project requires. These are the money numbers that go into a designer–client agreement. Budgeting a job is about allotting specific amounts of time and money, based on the approved fees and expenses in the designer–client agreement, for specific tasks that occur in the working of a project. Admittedly, these are somewhat arbitrary definitions of the terms. The view taken in this book is that they are related but different ways of thinking about design projects and money.

For budgeting, let the work breakdown structure (page 66) be the road map. Assign one person to each task, and identify the amount of time you think it will take to complete the task. When the job commences, make sure the person performing each task knows how many hours have been planned for the work. The person should alert the manager about any impediment to following this plan as soon as it occurs. With that knowledge, the manager has options: Extend the schedule, provide extra support, or even present the client with a change order, depending on the cause of the impediment.

There is a complex relationship between the project constraints of time, cost, and scope (see page 15) and reviewing budgets. It’s always about juggling opposing constraints and making the best decisions possible. For example, if the budget allocates three hours for completing design concepts, but nothing good has been created in that period, the designer must recalculate the budget to spend more time to develop a great design solution.

Attitudes About Money

Budgeting in design is another form of planning; an educated guess at a project’s financial implications. Real-world circumstances sometimes turn these plans upside down. No designer can anticipate every possible factor that may compromise a budget, but designers can understand their own work ethic and philosophical approach to money that may aid or subvert their budgets.

Pricing Philosophy

Design firms generally are driven by three philosophical attitudes:

• Client Demand Driven:

Whatever the client wants, they get. Responsiveness is key. Going the extra mile to please the client, which often means rounds of revisions, is fine. This designer believes service is king and financial rewards will come over the course of the client relationship, not necessarily via one project.

• Design Driven:

Quality and creativity are at the forefront, not money. These designers work until they achieve excellence, even if they exceed their allotted time on the project. They believe that doing great work will bring more and better clients, and the money will simply follow.

• Financially Driven:

Cash is king for these designers. They believe design is a for-profit business; if the client wants more changes or enhanced quality, they need to pay more for it. These designers believe there are always more clients and more projects, but a bird in the hand is worth more than speculation about the future.

Three Types of Estimates

You can use three major types of estimates to communicate costs to clients:

Ballpark Estimate:This is an initial rough estimate based on high-level client objectives, with a large margin for uncertainty. The deliverables, scope of work, and corresponding resource requirements may not be clear yet, so out of necessity, the estimate must allow for these things. Typically, a price range, rather than a fixed fee is stated.

Budgetary Estimate:This is a more accurate view of project-related costs based on a much clearer scope of work. It is contingent on a fairly accurate view of the work to be done, which still may be in a state of flux. As such, conditions and parameters should be stated—for example, “This estimate is based on available information, and will be reviewed based on approved design concept.”

Definitive Estimate:This is a time-consuming and detailed estimate created once the full scope of work, final deliverables, and detailed work flow are known. A full work breakdown structure (see page 66) is completed, the project is scheduled, and the team is assembled before the estimate is prepared.

Eight Payment Strategies

Rights and Compensation

One thing designers must consider in terms of money and design is ownership of the work being created. Who owns what, and how the work may or may not be used, is a negotiating point that also has financial implications. This concept is tied to the designer’s intellectual property rights and the client’s right to use the work they commissioned the designer to create.

Intellectual property (a legal reference to the creations of the mind: inventions, literary and artistic works, etc.) is debated by lawyers worldwide. In the United States and Canada, for example, all creative work is owned by its creator until the creator transfers ownership in writing to someone else. This is the cornerstone of copyright protection (legal protection that gives the creator of an original work exclusive rights to use that work within a certain period). Other countries may take different views and have different laws, so designers must understand what is true and legal in the country in which they practice design.

There are some complex rights and usage agreements that can affect a graphic designer. For example, in the United States many clients require designers to work under a work-for-hire contract, which is a written (not verbal) legal agreement between the designer and client stating that the client owns all work developed by the designer under the contract. In essence, it legally makes the client the creator of the work and affords them all the related rights of a creator. This isn’t a bad thing, but it means the client is now undisputedly the owner of the work. As such, a designer might want additional compensation.

It is important that the designer and client know who owns the work and how it may be used. For example, when a client owns outright an illustration that a designer developed for a pamphlet, the client can use that image in any future advertisement or on their web page, without paying the designer anything additional. Therefore, a designer would want to charge more for this kind of complete transfer of rights and ownership. Alternatively, it could be a negotiating point: Charge a lower fee, but the client has restricted usage rights for the work.

Compensation and the notion of intellectual property is a good topic for a designer to discuss with an attorney. You can also seek information from various design organizations, and share this information with your peers. Know your rights, know your client’s needs, and know the laws at the intersection of these two things.

Factors to consider when thinking about the material worth of usage rights and your corresponding fee for a design include

• The value placed on similar work (perhaps even for other clients)

• The category or media in which the work will be used

• The geographic location or area of distribution for the work

• How the client will use the work (for what purpose)

• How long the work will be used

• How many items will be produced that incorporate the work