Chapter 6. Warez (Software Piracy)

When people started selling the first computer programs on paper tape, tape cassettes, floppy disks, and CDs, people discovered that they could easily copy a program and share it with their friends. Such blatant copying prompted the programmer of an Altair computer BASIC interpreter to write an open letter to fellow computer hobbyists, urging them not to copy or pirate software illegally:

AN OPEN LETTER TO HOBBYISTS

By William Henry Gates III

February 3, 1976

To me, the most critical thing in the hobby market right now is the lack of good software courses, books and software itself. Without good software and an owner who understands programming, a hobby computer is wasted. Will quality software be written for the hobby market?

Almost a year ago, Paul Allen and myself, expecting the hobby market to expand, hired Monte Davidoff and developed Altair BASIC. Though the initial work took only two months, the three of us have spent most of the last year documenting, improving and adding features to BASIC. Now we have 4K, 8K, EXTENDED, ROM and DISK BASIC. The value of the computer time we have used exceeds $40,000.

The feedback we have gotten from the hundreds of people who say they are using BASIC has all been positive. Two surprising things are apparent, however, 1) Most of these “users” never bought BASIC (less than 10% of all Altair owners have bought BASIC), and 2) The amount of royalties we have received from sales to hobbyists makes the time spent on Altair BASIC worth less than $2 an hour.

Why is this? As the majority of hobbyists must be aware, most of you steal your software. Hardware must be paid for, but software is something to share. Who cares if the people who worked on it get paid?

Is this fair? One thing you don’t do by stealing software is get back at MITS[1] for some problem you may have had. MITS doesn’t make money selling software. The royalty paid to us, the manual, the tape and the overhead make it a break-even operation. One thing you do do is prevent good software from being written. Who can afford to do professional work for nothing? What hobbyist can put 3-man years into programming, finding all bugs, documenting his product and distribute for free? The fact is, no one besides us has invested a lot of money in hobby software. We have written 6800 BASIC, and are writing 8080 APL and 6800 APL, but there is very little incentive to make this software available to hobbyists. Most directly, the thing you do is theft.

What about the guys who re-sell Altair BASIC, aren’t they making money on hobby software? Yes, but those who have been reported to us may lose in the end. They are the ones who give hobbyists a bad name, and should be kicked out of any club meeting they show up at.

I would appreciate letters from any one who wants to pay up, or has a suggestion or comment. Just write to me at 1180 Alvarado SE, #114, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 87108. Nothing would please me more than being able to hire ten programmers and deluge the hobby market with good software.

Bill Gates

General Partner, Micro-Soft

Copying Copy-Protected Software

Despite Bill Gates’s pleas, software piracy not only thrived but also proliferated under the slang name warez. In the early days, software publishers tried to protect their products by shipping programs on copy-protected floppy disks, but other companies soon released special programs that could copy a copy-protected floppy disk, ostensibly for backup purposes.

Some software publishers shipped their programs with a hardware device called a dongle, which usually attached to the computer’s parallel port. Every time a program would run, it would check to see if this dongle was attached to the computer. If it didn’t find the dongle, the program would assume it had been copied illegally and would refuse to run.

Hackers quickly found ways to emulate these dongles using software, essentially tricking a program into thinking a dongle was attached to the computer when it wasn’t. Many companies even started selling software dongle emulators, such as Spectrum Software (www.donglefree.com) and SafeKey International (www.safe-key.com).

When fledgling online services such as America Online appeared, software piracy became even more rampant. Hackers formed software cracking groups and gave themselves names like Phrozen Crew, Fantastic Four Cracking Group, and the International Network of Crackers. These cracking groups competed against one another to grab a copy of copy-protected programs (usually games), remove the copy-protection scheme, and distribute the cracked copy of the program on BBSs and online services such as America Online.

To brag about their exploits, cracking groups would insert a screen that appeared whenever someone tried to run a cracked program. These screens, dubbed crack intros or simply cracktros, often displayed colorful graphics to publicize the name of the cracking group, their BBS number, acknowledgments to their friends, or just a silly message, as shown in Figure 6-1.

To see more examples of cracktros created by various cracking groups, visit Defacto2 (www.defacto2.net), Flashtro (www.flashtro.com), or the World of Cracktros (http://cracktros.planet-d.net).

Among those who didn’t partake of cracked programs, copy protection did prevent casual copying, but it also prevented legitimate users from making backup copies of their software. One spilled drink on a copy-protected floppy disk could effectively ruin a $495 program.

To copy-protect their software without inconveniencing legitimate users too much, software publishers have tried a variety of schemes. Some of these methods involved typing in special codes printed in the user manual every time the program started up. Another method involved “locking” a program to a specific hard disk. This required you to “unlock” and delete the program from the first computer before you could use the installation disk on a different computer.

This anecdote may be apocryphal, but it’s said that Microsoft even attempted a bizarre form of copy protection on its MS-DOS version of Microsoft Word. Periodically, the program would check to see if it was running off a legitimate copy-protected floppy disk. If it detected a pirated copy, the program would retaliate by trashing any files it could find. Nobody knew about this form of copy protection until Word happened to trash a computer journalist’s files. Even worse, the journalist had been running a legitimate copy of Microsoft Word.

Microsoft quickly denied that this form of copy protection existed, then blamed a summer intern for slipping the retaliation feature into Microsoft Word without the company’s permission or knowledge.

Although consumers hated it, copy-protection mechanisms remained on most software programs until hard disks became cheaper and more common. Users then needed to copy their software from a floppy disk to their hard disk. Instead of physically blocking their programs from being copied, software publishers resorted to using serial numbers for validation.

Defeating Serial Numbers

To install many programs, you have to type in a serial number, usually found on an enclosed registration card or (if you downloaded the software over the Internet) included in an email message from the software publisher. By typing in a valid serial number, typically an unusual combination of letters and numbers, you “unlock” the software and install it on your computer.

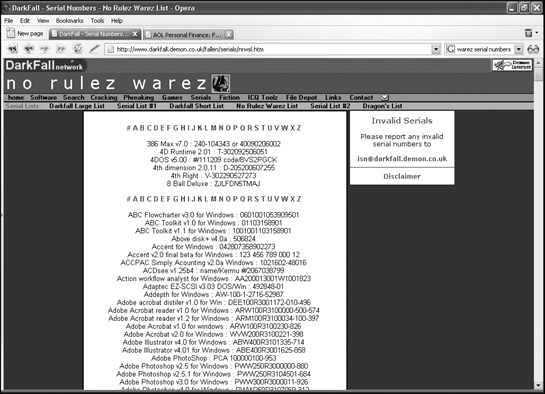

Of course, some people found that serial numbers were easy to defeat. They’d simply copy their valid serial numbers and pass them among their friends. Since they no longer had to use their programming skills to crack any type of copy-protection, warez pirates simply set up websites with huge lists of valid serial numbers for different programs that anyone could use right away, as shown in Figure 6-2.

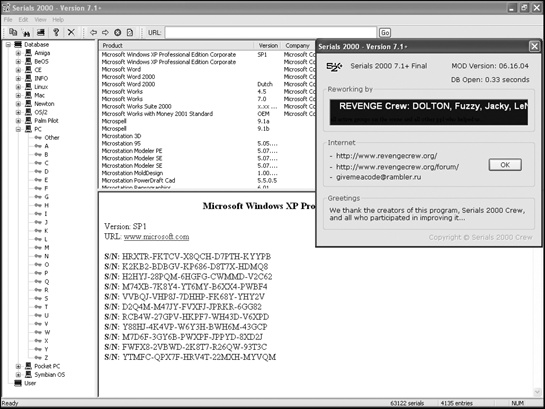

Besides storing serial numbers of different programs on websites, which could get shut down, other hackers have stored serial numbers in databases that you can download, search, and update, as shown in Figure 6-3.

One problem with this approach is that expanding the database typically requires people to share their valid serial numbers. Since few people are likely to do this, hackers have created special serial number generation programs that use the same algorithms used by the programs themselves.

Although serial numbers appear to be random combinations of numbers and letters, they’re actually created by a mathematical formula. So although it’s nearly impossible to guess a valid serial number for a program, it’s often possible to reverse engineer a program to determine the specific formula it uses during validation.

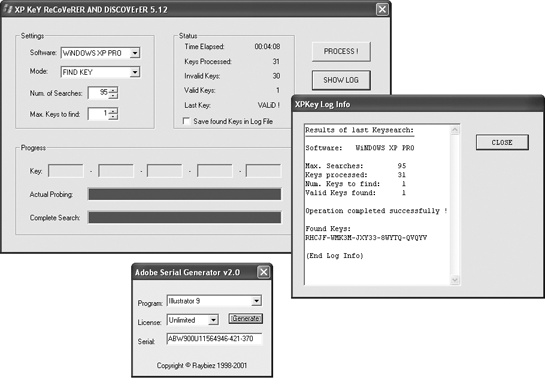

To reverse engineer a program, hackers use special programs called disassemblers, which can convert a program into assembly language instructions. Once hackers understand the exact verification method, they can create a program to generate random serial numbers that match the target program’s serial number verification formula. Most companies use the same serial number verification formula for different products, so hackers develop different serial number generators for different vendors, such as Microsoft and Adobe, as shown in Figure 6-4.

To find websites that list serial numbers or that offer serial number generators, visit CrackHell (www.crackhell.com), KeyGen (www.keygen.us), MegaZip (www.megazip.com), or Serials (www.serials.ws).

Note

Be careful when visiting any hacker sites, as they’ll often bombard you with pop-up windows loaded with pornography and try to sneak spyware (see Chapter 20) onto your computer. For safety, browse hacker sites on a non-Windows computer such as one running Linux or Mac OS X.

Defeating Product Activation

The latest attempt to curb software piracy involves product activation. When you install a program that uses product activation, it gathers information about the computer’s CPU, hard disk, graphics card, and other hardware to create a unique identifier. Then the program sends this information, along with the serial number entered by the user, to the software publisher. This ties a specific serial number to a particular computer, preventing anyone from reusing that serial number on another computer.

Product activation defeats the rampant sharing of valid serial numbers, but still can’t defeat serial number generators since a new serial number can always be generated to be linked to another computer.

More troublesome, from a user’s point of view, is that product activation can be a nuisance at best and a major headache at worst. Intuit once sold its popular TurboTax program with product activation that, in many cases, actually prevented people from installing and using the software they legitimately bought. Symantec had similar problems when it started including product activation with its Norton Antivirus program. In Symantec’s case, the product activation would ask for a serial number every time the computer booted up. No matter how many times the user typed in his valid serial number, the product activation would eventually shut down after a few days and stop Norton Antivirus from working altogether. In both cases, bugs in the product activation program wound up punishing legitimate users.

Product activation may stop ordinary computer users from pirating software, but it does nothing to stop determined hackers, who are the people most likely to pirate software in the first place. As soon as Microsoft introduced product activation for Windows, hackers developed product activation patches that could modify the operating system and prevent its product activation feature from working, as shown in Figure 6-5.

Like serial numbers and copy protection, product activation discourages casual copying but with added nuisance and expense for the software publisher. No matter what method software publishers use to guard against piracy, they’ll only succeed in slowing down software pirates, not eliminating them. Product activation might work in theory, but as every hacker knows, theory means nothing in the real (and virtual) world of computers.

Warez Websites

In the old days, people pirated software by copying a program onto a floppy disk and giving the copy to someone else. Later, pirates ran private BBSs and swapped software through the telephone lines.

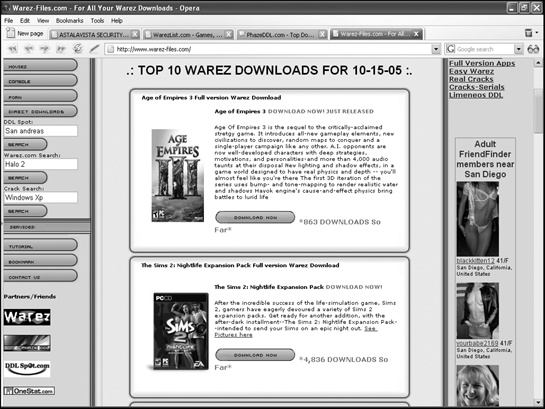

When pirates discovered the Internet, they set up their own websites for trading illicit software, as shown in Figure 6-6. Some popular lists of hacker sites include Warez List (www.warezlist.com), DirectDL (www.directdl.com), AllSeek (http://top.allseek.info), CrackDB (www.crackdb.com), and Warez Files (www.warez-files.com).

Since websites can easily be tracked by the authorities, pirates soon moved on to swapping programs through filesharing networks (such as FastTrack, Gnutella, and BitTorrent) and Usenet newsgroups.

One problem with filesharing networks is that authorities can track down any user’s Internet Protocol (IP) address and then, by linking a computer’s IP address to a physical address, could often nab blatant file sharers and punish them.

That’s why more pirates have flocked to BitTorrent. Unlike traditional filesharing networks like Gnutella, you don’t search anyone else’s computer. Instead, you have to visit a website, called an indexing site, that provides a list of files you can download, such as movies, programs, or music. Once you click a file, the indexing site directs you to all the computers that have that file.

Even more remarkable is that as soon as you start downloading a file, BitTorrent lets you simultaneously share that file with anyone else. Not only does this speed up file transfers, but it also insures that if your computer loses connection with another computer, you can still download the parts of the file you need from a different computer. Because of its ability to handle large files and its speed in downloading, BitTorrent has quickly become a favorite among pirates of all kinds.

Usenet Newsgroups: The New Piracy Breeding Ground

While most pirates use BitTorrent to share files, many pirates also use the seemingly antiquated Usenet newsgroups as well.

On Usenet newsgroups, pirates can upload programs anonymously, and anyone can download them anonymously as well. No matter how hard they might try, the authorities can only identify that software piracy is occurring; they can’t trace the offenders.

Initially, Usenet newsgroups were rather cumbersome compared to the point-and-click convenience of web pages. Trying to find a particular program meant scouring through multiple newsgroups. Also, Usenet newsgroups imposed a fixed file size of 10,000 lines per file, which meant that large files, such as pirated programs, had to be broken into parts, which were downloaded individually and then reassembled. If even one part were missing, the program wouldn’t work. As a result, Usenet newsgroups often proved too troublesome for less tech-savvy users to handle.

To make searching for files among newsgroups easier, programmers have created a new file format, dubbed NewzBin (NZB), to turn Usenet newsgroups into a fast indexing and downloading resource for warez.

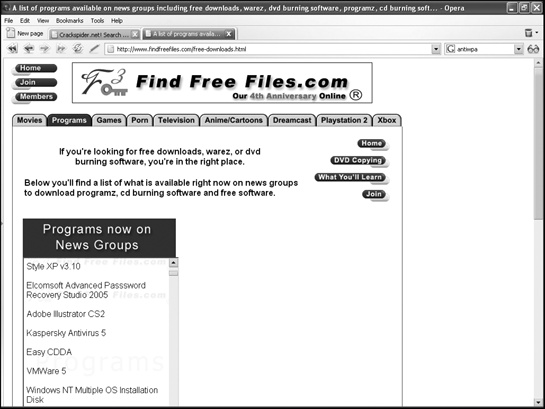

To search a Usenet newsgroup for files, you can visit the more common ones, such as alt.binaries.warez, or you could use a Usenet newsgroup search engine such as alt.binaries.nl (http://alt.binaries.nl), BinCrawler (www.bincrawler.com), Newzbin (www.newzbin.com), or Find Free Files (www.findfreefiles.com), as shown in Figure 6-7.

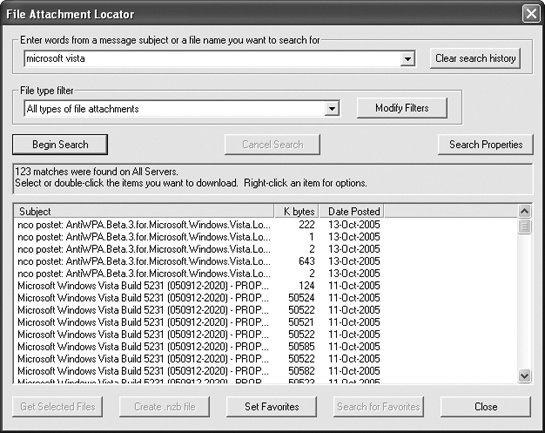

Once you find the pirated program you want, you can use a newsreader program that supports NZB files, such as NewsMan Pro (www.newsmanpro.com), Binary Boy (www.binaryboy.com), NewsBin Pro (www.newsbin.com), or News Rover (www.newsrover.com), as shown in Figure 6-8, to download it without having to search manually.

Combine a NZB-enabled newsreader with a high-speed, dedicated news server such as NewsDemon (www.newsdemon.com), GigaNews (www.giganews.com), or AstraWeb (www.news.astraweb.com), and you can start downloading all the warez you want without anyone knowing who you are.

People have been pirating software ever since computers have been around, and that is not going to change anytime soon. People in developing nations and countries such as China and Russia pirate software because they can’t afford it otherwise. That doesn’t make piracy right, but given that the cost of a single copy of Adobe Photoshop is more than most people in the world earn in a month, it’s safe to say that piracy will always be a more enticing option than buying software honestly, at least for some people.

To fight back against piracy, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) have used several techniques with varying degrees of success. Initially, the MPAA/RIAA targeted individuals sharing enormous numbers of files off their computers, such as a thousand or more. By suing these individuals, the MPAA/RIAA hoped to scare away others from sharing files too.

To further discourage piracy, the MPAA/RIAA also “poisoned” the filesharing networks with bogus files. If people kept downloading bogus files, the MPAA/RIAA hoped that they would abandon the filesharing networks and turn to legitimate ones instead.

Next, the MPAA/RIAA started targeting the companies that made the filesharing programs. During 2005, the MPAA/RIAA managed to sue and shut down the publishers of Grokster and WinMX. By taking away the software used to swap files, the MPAA/RIAA hoped to shut down the filesharing networks one by one.

For their latest tactic, the MPAA/RIAA has targeted the search engines that provide access to pirated files, such as BinNews.com, which allowed people to search Usenet newsgroups for warez, or IsoHunt.com, which provided links to BitTorrent files, such as full-length movies or major applications like Adobe Photoshop.

Generally speaking, finding a pirated program can be tedious—and getting that pirated program to work can sometimes be more frustrating than going out and buying it. For hackers, software piracy is a challenge. For the average user, piracy is appealing only when it’s convenient. But to dedicated software pirates, piracy can be a way of life, and nothing the software publishers can do will ever stop it.

[1] Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) was the company that made the first personal computer, the Altair 8800.