Chapter 1. The Hacker Mentality

Hackers are no more criminals than lawyers, politicians, or TV evangelists are. (Okay, so maybe that’s not the best analogy.) The point is that being a hacker doesn’t necessarily make you a criminal. Your attitude makes you a hacker, but if you’re not careful, your actions can make you a criminal.

With the news media ready to blame every computer glitch on malicious hackers, too many people get a one-sided point of view that hackers are just completely evil, bent-on-destruction-of-the-civilized-world malcontents who’d love nothing better than to demolish everything good in society and sow terror and chaos in their wake. (Of course, that’s the same one-sided view used to slander some people as “terrorists” or “insurgents” while others call those exact same people “freedom fighters” and “patriots,” but that’s a subject for Chapter 17.)

Whether a hacker fits the stereotypical image of a nerd with pocket protectors, thick glasses, and awkward social skills is irrelevant (and most don’t). A hacker is not defined by how he looks or behaves, but rather by how he thinks, and the most crucial aspect in developing a true hacker mentality is learning how to think for yourself.

Questioning Authority

To truly start thinking for yourself, begin by questioning authority. This doesn’t mean rebelling against, overthrowing, or ignoring authority. It means listening to what any authority figure or organization tells you and discerning their motives. As every con artist knows, the first step to getting someone to do what you want is to hide your own motives and pretend that you really want to help them instead. (See Chapter 13 for more information about how con games work over the Internet.) Questioning authority means nothing more than asking how the authority figure or organization will benefit if you do what they tell you to do.

There are three possible reasons an authority figure or organization would tell you something:

It really is for your own good.

It’s all they know at the moment.

It’s really for their benefit, not yours.

Parents tell children to eat their vegetables not because they want to torture their kids or make them miserable, but because eating a balanced diet is actually good for kids, no matter how distasteful they may find broccoli or spinach to be. Similarly, governments tell their citizens how to survive natural disasters or avoid trouble while traveling in foreign countries because that information really can help people survive. Parents may benefit by having healthier kids and saving money buying carrots and celery instead of hamburgers and french fries, but financial motives are secondary to their children’s health. Similarly, governments may benefit from having live taxpayers rather than dead citizens, but that’s secondary to the real motive of basic public safety. More often than many people might like to admit, authority figures and organizations do have your best interests at heart, which is why blindly rebelling against all forms of authority is ultimately as counterproductive as ignoring traffic lights to protest government interference and then getting hurt—or hurting someone else—when you crash your car.

Of course, authority figures and organizations don’t always have such pure, altruistic motives at heart. That’s why it’s important to question authority. Many times, the authorities really don’t know what they’re doing. If you follow their orders without question, you’re the one who will suffer any consequences, not them.

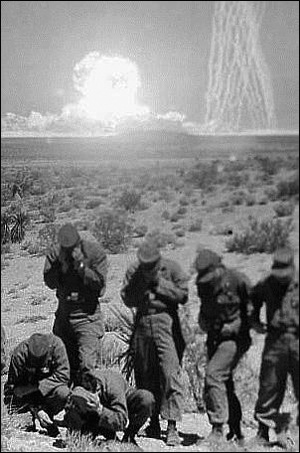

When the United States government exposed Army soldiers to atomic bomb blasts in the 1950s, as shown in Figure 1-1, they didn’t intend for the soldiers to get hit by radiation so they could later die of leukemia. At the time, the government wanted to study the effects of atomic bomb blasts among conventional military forces, so they took all the precautions they believed necessary to protect the solders’ welfare. In this case, the government’s actions were born out of ignorance. However, the subsequent decision to hide the problematic test results and avoid responsibility for the soldiers’ health falls more under the category of malicious self-interest. Ignorance can be forgiven only when combined with accountability, and that’s something few authorities will ever take upon themselves. You should always question not only what anyone in authority wants you to do, but why they should have any authority over you in the first place.

More frightening is when authorities act purely for their own benefit while stealing, injuring, or killing the rest of us. Dictatorships throughout history, in countries such as China, Germany, Afghanistan, North Korea, Iraq, Zimbabwe, Japan, Iran, Cuba, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, have routinely executed or imprisoned anyone who questioned their authority. Under such dictatorships, the citizens are supposed to do all the work while the authorities enjoy all the money (which is something most Americans can empathize with when income tax time rolls around April 15, just before Congress votes itself another pay raise and takes one of its many recesses).

Such blatant abuses of authority are perpetrated by individuals and corporations as well as by governments. For instance, consider Jim Jones, who founded the People’s Temple as an urban Christian mission that offered free meals, beds to sleep in, and even jobs, along with a sense of community. In San Francisco, where the group settled, city officials such as Mayor George Moscone, Supervisor Harvey Milk, and Assemblyman Willie Brown supported Jones (in return for the support of the People’s Temple at election time). Even newspapers, including the San Francisco Chronicle, praised Jones and his People’s Temple for setting up drug treatment clinics, child care services, and senior citizen programs.

Such benevolent actions masked the megalomania of Jim Jones, who ultimately led his church to Guyana, where he physically and emotionally abused his followers before ordering them to commit mass suicide by drinking cyanide-laced fruit punch.

Tobacco companies may be spending money on anti-smoking advertisements, but they’re still in the business of making and selling cigarettes. The United States may feel justified in using military force to promote democracy in Iraq, but it has yet to send in the Marines to promote democracy in Saudi Arabia. Islamic radicals may claim they’re fighting pro-Western dictatorships in the Middle East, but they’re still blowing up innocent Muslim women and children with their car bombs. Mother Teresa may have had her critics, but none of them can deny that she tried to do good. Jim Jones had his supporters, but none of them can deny that he deliberately did something bad.

Too often, good actions can mask bad intentions. That’s why you need to question authority. If you don’t, you may become part of the problem, or as the American legal system likes to put it, “an accessory to the crime.”

Questioning Assumptions

As any oppressive authoritarian regime knows, physical restraints are less effective than mental ones. Why build prisons when you can brainwash people into doing what you want? Because your thoughts define your limitations, you must question your own assumptions.

Assumptions aren’t necessarily bad. When you send email, you assume it’s going to get to the intended recipient. When you save a file, you assume it’s going to be on your hard disk the next time you want it. An assumption is basically a mental shortcut that allows you to think about something else. Few people would send email if they had to worry whether it would really arrive at its destination or not, and almost nobody would use a computer if they couldn’t assume their files would still be on their hard disk after saving them. Unfortunately, assumptions aren’t always right. Email doesn’t always reach its intended recipient, and sometimes when you save a file, a virus or computer crash can make it disappear.

Although useful, assumptions can lead to several problems:

Assumptions may be based on beliefs rather than facts.

Assumptions may be based on facts taken out of context.

Assumptions, whether based on facts or beliefs, limit and restrict thinking.

In the world of technology, Bell Telephone created its telephone monopoly and assumed people would use it to make phone calls the way Bell Telephone intended. When phone phreakers defied this assumption and rummaged through the telephone system on their own, the facts proved that phreakers were manipulating the phone system in ways that even the telephone company had never dreamed of. (See Chapter 2 for more on phone phreaking.)

Many of the flaws in computer security stem from assumptions based on beliefs rather than facts. Computer scientists believe that a particular program is secure—until hackers discover that manipulating a program feature in an unintended manner can crack open that computer’s defenses.

Sometimes assumptions can be based on facts that hold true in certain circumstances but not in others. When Microsoft created MS-DOS and Windows, it assumed that those operating systems were safe, and they were—until people began connecting computers to local area networks (LANs) and the Internet. In isolation, MS-DOS and Windows were safe platforms. In a network, these same operating systems became breeding grounds for viruses, Trojan horses, and worms (see Chapter 4 and Chapter 5).

When computer scientists created standards for sending and receiving email over the Internet, they assumed that people would only send emails to people they knew. Unfortunately, they never foresaw that free message delivery would attract unscrupulous salespeople and create the nuisance known as spam (see Chapter 18).

Even if assumptions are based on facts, they still limit your thinking. When faced with a computer login screen, most people automatically assume that the only way to get past this first line of defense is to type a valid user name and password, either by stealing or guessing it. If you make that assumption, however, you might never come up with alternate approaches, such as flooding the computer with a massive chunk of data that has an executable program tacked on the end. This can overload the computer’s memory and allow the executable program to run without the computer recognizing it, essentially bypassing any security measures, including a request for a valid password. (See Chapter 9 for more information about sneaking past a computer’s defenses.)

By identifying assumptions, you can better understand how they may have influenced your current thoughts and actions. Then you can deliberately break out of their inherent restrictions by challenging your assumptions. You might discover something new simply by looking at the world from another point of view.

Developing Values

Of course, if you do nothing but question authorities and assumptions, you’ll wind up reacting to life rather than pursuing it, much like adolescents who define themselves by rebelling against their parents’ wishes and values, rather than choosing the life they want to live on their own.

So in addition to questioning authorities and assumptions, hackers also develop a sense of values to guide their actions. Values, like assumptions, are beliefs, but they are beliefs generated from within and not imposed by others, such as parents or governments. At the simplest level, values help people make choices, such as whether they choose Linux over Windows or learn the Perl programming language rather than C++.

Shared values can forge friendships (for an example of people using technology to promote their ideas, visit Republican Voices at www.republicanvoices.org); conflicting values can tear people apart (see Chapter 17 for more information about hate groups and terrorists).

Anyone can choose values, especially values that will garner favor from others. For example, politicians may endorse the values of religious organizations just to gain their political support, and then promptly ignore those same religious values (“Thou shalt not commit adultery” or “Thou shalt not kill”) when they finally get elected to office. What’s more important than the values you choose is whether you abide by them all the time or only when it’s convenient, which reveals your true values.

Hypocrisy is what fuels rebellions in the first place, causing others to question an authority figure’s standing as an authority and reject any values that person may want to force on them (see Chapter 16 for more information about political activism on the Internet). When authorities want to mask their own hypocrisy, they often resort to censorship (see Chapter 11) and lies (see Chapter 15 for more information about propaganda).

In the world of computer hacking, people only know who you are by your online actions. Your identity may be anonymous, but your true personality isn’t, and that’s what makes the world of computers both liberating and terrifying at the same time, depending on who you really are.

The Three Stages of Hacking

The mentality of a hacker typically goes through three stages, whether the hacker is merely exploring a new operating system or learning social skills for work situations:

Stage I: Curiosity

Stage II: Control

Stage III: Conscious intent

Hackers come from different backgrounds and cultures, but every hacker shares the same sense of curiosity that drew him or her to the technology in the first place. At the initial curiosity stage, hackers simply want to know how things work, whether they’re studying the Internet, a copy-protected DVD, or the telephone system. At the outset, hackers want to understand what’s possible and why.

Once they learn enough about a particular system, hackers can graduate to the second stage of hacking, in which they gradually learn to control and manipulate the system. Any problems that hackers cause at this point, such as crashing a computer or erasing a hard disk, occur more often out of sheer clumsiness than deliberate intent.

Hackers reach the third and final stage when they put their newfound skills to work for a purpose. At this point, hackers seek a specific result; whether it’s good or bad is irrelevant. Hackers want to achieve whatever goal they set for themselves, and they’re willing to pursue it with relentless determination until they get there.

No matter what the intention or the result, hacking involves tackling new challenges and stimulating your mind. It sometimes involves breaking the law and trespassing on other people’s property, but many times it’s just about having fun. Whether hackers are rerouting phone calls, modifying software, or stealing passwords over the Internet, hacking isn’t about proving anyone wrong. Hacking is about proving that other ways of doing things can also be right.