Chapter 18. Identity Theft and Spam

technology writer

The rise of computer crime and armed robbery has not eliminated the lure of caged cash.

Not everyone who can manipulate a computer is a hacker, and not every hacker is a computer expert. Hacking is an attitude of exploration. However, real hackers can often use their computer skills and knowledge to take advantage of other people. When hackers want to use their computer skills to steal from other people, they usually engage in some form of identity theft. When hackers want to use their computer skills to bombard people with advertisements for legitimate (and not-so-legitimate) products, they use spam.

Whatever the motivation may be, the end result of identity theft and spam is the same: Someone is hacking your life without your consent.

Understanding Identity Theft

Computers aren’t required to conduct identity theft, but they do make it easier and more convenient. In simple terms, identity theft involves masquerading as someone else so they get stuck paying your bills. This can be as easy as a waiter copying down your credit card number when you pay your dinner bill and then using it to order expensive merchandise by mail or over the Internet.

On a more extreme level, identity theft could occur when someone uses your name, Social Security number, current address, and date of birth to access your bank accounts, take out loans, and even to commit crimes that will be traced back to you.

How identity theft works

Relatively few people know you personally, so most people you do business with or otherwise meet in the course of your daily life rely on unique information to identify you, such as your full name, date of birth, Social Security number, mother’s maiden name, zip code, and credit card number.

For all intents and purposes, however, anyone who possesses this information can trick others into thinking that he or she is you. The identity thief needn’t have the skills to physically mimic your behavior, appearance, or manner of speaking to assume your identity.

Minimizing the threat of identity theft

Anyone can become a victim of identity theft. Just ask Oprah Winfrey, Steven Spielberg, and Tiger Woods. But when identity thieves target ordinary people, it’s almost always because they have the opportunity, not because they took the time to target you specifically.

Identity thieves usually get your personal information one of three ways:

Hacking into corporate computers that store your personal information, such as the databases kept by banks and credit card companies. Hackers can also target any large company that stores its employee records on a computer.

Dumpster diving in your trash or the trash of a company where you work or do business.

Phishing and other social engineering tricks to get your personal data.

If a hacker breaks into a bank’s computer and steals your account numbers and Social Security number along with your mother’s maiden name, there’s not a thing you can do about it. Your personal information is only as secure as the computers it’s stored on, so it’s important to share such data only with trusted institutions. And then pray that they protect it as best they can.

Dumpster diving just means digging through someone’s trash looking for something valuable. Identity thieves look for documents with personal information printed on them, such as unopened credit card offers that already have a name and address on them. The identity thief can then fill out the application and have a credit card sent to you. Next, unless you have a locking mailbox, he watches your mail until the new card arrives. At this point, the identity thief can start racking up charges on a credit card that you don’t even know exists (but that has your name printed on it, as will the bills that start pouring in a month later). Military bases are popular places for identity thieves to work because these locations often give them access to mail for a large number of people, which they can then intercept even without being a postal employee.

Another objective of dumpster diving is finding useful items such as bank account numbers on deposit slips, credit card bills (with credit card numbers printed on them), or tax return information (which can include Social Security numbers).

To protect yourself against dumpster divers, shred anything that contains personal information, and destroy credit card applications to prevent someone from filling them out without your knowledge. For further protection, get a mailbox with a lock.

If you’re truly paranoid, get a post office box and have all financial information, such as credit card and bank statements, sent there. Of course, you still have to trust the people sorting the mail at your post office.

Finally, identity thieves can get your personal information through phishing, either by sending you email or calling you on the phone and pretending to be a legitimate company. To reach as many potential victims as possible, identity thieves may send a bogus email to thousands of people at once (a more malicious form of spam) and wait for a certain percentage of the recipients to fall for the scam and enter their personal information on their website.

Another strategy of phishers is to call potential victims directly, typically targeting senior citizens. Phone call phishing takes more time and effort, but can still yield the desired personal information.

In rare cases, identity thieves may set up sidewalk polls and ask respondents to provide their name, address, and phone number in the process. Since people aren’t giving away anything that can’t be found in a telephone book, they often see nothing wrong with doing this. What they don’t realize is that they’ve made the identity thief’s job a lot easier. He can use this information to find that person’s Social Security and credit card numbers later.

The key to minimizing your risk of becoming an identity theft victim is to give out your personal information only sparingly, shred any papers with information that someone could exploit or use to find additional information about you, and never respond to unsolicited phone calls or emails.

Also be careful when giving out information to “trusted” organizations like banks or businesses. While they may request sensitive information like Social Security numbers for “marketing” purposes, you can always refuse to give them this information if it isn’t legally required. By restricting who has access to your personal data, you limit the chances that someone can steal your personal information from someone else.

Protecting your credit rating

Despite taking every precaution, you could still fall victim to an identity thief. To help you monitor and protect your credit rating, start by getting a free copy of your credit report, which you can request once every 12 months in one of the following ways:

Visit www.annualcreditreport.com.

Call 877.322.8228 (toll free).

Fill out an Annual Credit Report Request Form and mail it to Annual Credit Report Request Service, P.O. Box 105281, Atlanta, GA 30348-5281. You can print this form from the www.ftc.gov/credit website.

Under federal law, you can also receive a free copy of your credit report if a company takes adverse action against you, such as denying your application for credit, insurance, or employment. If this happens, you can request a free copy of your credit report within 60 days of receiving notice of the action. Reviewing your credit report can help you determine whether an identity thief has ruined your credit rating.

If you want to buy a copy of your credit report, contact one of the following:

800.685.1111; www.equifax.com | |

888.EXPERIAN (888.397.3742); www.experian.com | |

800.916.8800; www.transunion.com |

To avoid receiving credit card offers in the mail (and having to shred them to protect yourself), you can have credit card companies stop sending you their applications in the first place. To opt out of credit card offers by mail, call 1.888.5.OPTOUT (1.888.567.8688). Finally, create a document with all the bank and credit card phone numbers to call in case you need to close an account in a hurry.

Protecting your identity is much easier than trying to clean up your life after an identity thief has struck, so it makes sense to take the time to prepare now. For more information about identity theft, visit the following websites:

Identity Theft Resource Center | |

Federal Trade Commission | |

Privacy Rights Clearinghouse | |

Identity Theft Prevention and Survival | |

Fight Identity Theft |

Spam: Junk Mail on the Internet

Even if you use the Internet infrequently, you’ve probably been spammed by a long list of junk email from companies advertising products from the totally useless (bogus vitamins) to the illegal (child pornography), offering “free” vacation giveaways, or promoting moneymaking schemes. Unlike newspaper or magazine advertisements that you can ignore without losing a moment’s thought, spam just doesn’t seem to leave you alone.

Spamming means sending unsolicited messages to multiple email accounts or Usenet newsgroups. Victims of spamming must then take time to delete the unwanted messages so they can make room in their inboxes for useful email. Spam can include anything from legitimate advertisements to scams and bogus messages from identity thieves trying to phish for personal information. One of the more common types of spam involves chain letters or other suspicious “business opportunities” like this one:

$$$$$$$$ FAST CASH!!!! $$$$$$$$

Hello there, Read this it works! Fellow Debtor: This is going to sound like a con, but in fact IT WORKS! The person who is now #4 on the list was #5 when I got it, which was only a few days ago. Five dollars is a small investment in your future. Forget the lottery for a week, and give this a try. It can work for ALL of us. You can edit this list with a word processor or text editor and then convert it to a text file. Good Luck!!

Dear Friend,

My name is Dave Rhodes. In September 1988 my car was repossessed and the bill collectors were hounding me like you wouldn’t believe. I was laid off and my unemployment checks had run out. The only escape I had from the pressure of failure was my computer and my modem. I longed to turn my avocation into my vocation.

This January 1989 my family and I went on a ten day cruise to the tropics. I bought a Lincoln Town Car for CASH in February 1989. I am currently building a home on the West Coast of Florida, with a private pool, boat slip, and a beautiful view of the bay from my breakfast room table and patio.

I will never have to work again. Today I am rich! I have earned over $400,000.00 (Four Hundred Thousand Dollars) to date and will become a millionaire within 4 or 5 months. Anyone can do the same. This money making program works perfectly every time, 100 percent of the time. I have NEVER failed to earn $50,000.00 or more whenever I wanted. Best of all you never have to leave home except to go to your mailbox or post office.

I realized that with the power of the computer I could expand and enhance this money making formula into the most unbelievable cash flow generator that has ever been created. I substituted the computer bulletin boards in place of the post office and electronically did by computer what others were doing 100 percent by mail. Now only a few letters are mailed manually. Most of the hard work is speedily downloaded to other bulletin boards throughout the world.

If you believe that someday you deserve that lucky break that you have waited for all your life, simply follow the easy instructions below. Your dreams will come true.

To further entice people, many spam chain letters include headings such as “As seen on Oprah” to lend them credibility. No matter how they disguise themselves, however, chain letter spam just another form of pyramid scheme (see Chapter 13) in which a few people benefit at the expense of everyone else.

Why Companies Spam and How They Do It

Nobody likes to receive spam because it wastes time and clogs email inboxes, yet many companies continue to send it anyway because, unlike direct mail and other forms of advertising, spamming is essentially free. For the cost of a single Internet account, anyone can reach a worldwide audience potentially numbering in the millions. In the eyes of spammers, even if they upset 99 percent of the people on the Internet, having 1 percent buy their product makes it all worth the trouble.

When sending spam, there’s no need to type multiple email messages either; just as bulk mailers never lick their stamps, bulk emailing software automates the process for spammers. Click a button and you, too, can scatter unwanted email messages across the Internet.

Spammers are often stereotyped as scammers and con artists, but many are legitimate businesses that see spam as a low-cost, low-risk method for reaching potential customers. Of course, they realize that most people don’t like receiving spam so they substitute euphemisms like “bulk email marketing.” So the next time hordes of unwanted messages clog your email account, relax. You’re not receiving spam; you’re receiving bulk email marketing messages. Now don’t you feel better?

To learn more about spam from the spammer’s point of view, visit the websites of companies that sell bulk emailing programs, such as ClickZ Network (www.clickz.com), Internet Marketing Technologies (www.marketing-2000.net), Email Marketing Software (www.massmailsoftware.com), MailWorkz (www.mailworkz.com), or MTI Software (http://desktopserver.com).

Collecting email addresses

Spammers often flood Usenet newsgroups, where they can target their products to people with specific interests. For example, a spammer selling vitamin supplements will likely find a receptive audience in the misc.health.alternative newsgroup.

Of course, newsgroups represent only a fraction of potential customers on the Internet. Before spammers can flood the Internet with their messages, they need a list of email addresses. Although email lists can be bought, they are not always accurate or up to date. So spammers use email address extracting programs to build their own lists. These programs harvest addresses from three sources: newsgroups, websites, and database directories.

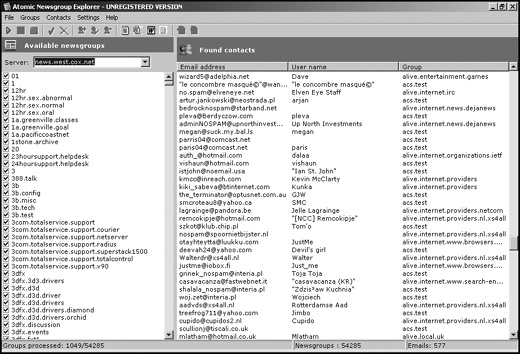

Newsgroup extractors

When you post a message to a Usenet newsgroup, your message appears with your email address. Newsgroup extractors simply download messages stored in a Usenet newsgroup, strip away the text, and store the return email addresses, as shown in Figure 18-1.

To prevent your email address from getting sucked up by a newsgroup extractor, use a phony address or an anonymous remailer when posting messages to a newsgroup. Although this will prevent other newsgroup users from contacting you directly, it also prevents spammers from flooding your account with garbage.

Because newsgroup extractors harvest thousands of email addresses at once, some people substitute the @ symbol in their address with the word AT, such as swapping [email protected] with joesmithATyahoo.com. Initially, email extractors wouldn’t recognize the word AT in the middle of an email address, but newer versions are smart enough to replace the word with the @ symbol, so even this technique is slowly losing its effectiveness.

Website extractors

Website extractors work just like newsgroup extractors except that they pull their email addresses from websites. When people create personal websites, they often provide a link where visitors can reach them. For a business website, they often list a number of company contacts, such as salespeople, technical support people, and even the CEO and president. Spammers prowl the Internet, with the guidance of search engines, to find web pages and pluck email addresses to store for future use.

To trick website extractors, many people replace characters in their email address with the ASCII code equivalents. So, rather than type the @ symbol, web page designers can substitute the ASCII code equivalent of the @ symbol, which is @, as shown below.

<html> <body bgcolor="#FFFFFF" text="#000000"> E-mail: joesmith@yahoo.com </body> </html>

The website extractor will probably strip away the invalid joesmith@yahoo.com, even though this email address appears correctly as [email protected] when viewed in a browser window.

Unfortunately, the latest email extractors can even snare email addresses masked by ASCII codes and convert them into valid ones, so many websites now display their email addresses as a graphic image. People will know how to type it in correctly but email extractors won’t, which can stop them for now.

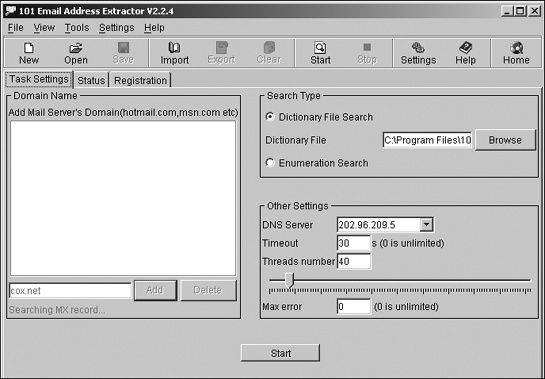

SMTP server extractors

An SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol) server is a computer that sends and receives email. An SMTP server extractor is a program that retrieves valid email addresses from an SMTP server, as shown in Figure 18-2.

This is how it works. First, the extractor makes up an email address and asks the SMTP server if it’s valid. It repeats this process indefinitely with fabricated addresses until it stumbles across a valid one that it can store for future spamming. To snare as many valid email addresses as possible, SMTP extractors typically target the servers of Internet service providers (ISPs), which can have thousands of customer email addresses waiting to be discovered.

P2P network harvesters

When people join a filesharing network to swap music, movies, or programs, they often type in their email address, which anyone else on that filesharing network can view. This is yet more fertile territory for spammers in search of email addresses. To protect yourself, never type your email address anyplace where others might be able to view it without your knowledge. To make matters worse, many people, when they configure a filesharing program, inadvertently share all the files on their computer, allowing spammers to peek inside and copy address books from their email program, such as Microsoft Outlook. With that information, the spammers can start spamming you and all the people you know.

Phishing for email addresses

Responding to pressure from people annoyed by telemarketers, the government created a Do Not Call list (www.donotcall.gov) where people could register their phone numbers. Telemarketers then had to scrub their phone lists to remove any numbers stored on this Do Not Call list.

So back in 2004, one spammer mimicked the Federal Trade Commission’s site with his own bogus Do Not Spam site. The idea was that you could type in your email address here and spammers would be barred from sending you email. Unfortunately, this site was actually run by a spammer in the first place, so anyone who registered there wound up getting more spam. The Federal Trade Commission quickly shut down that bogus website, but the spammer had already succeeded in harvesting a huge list of valid email addresses.

In 2005, another phisher used spam to send out a Trojan horse. Anyone foolish enough to run the attached file installed the Trojan horse, which sat quietly on the infected computer until it detected the user visiting an online banking website. Then the Trojan horse would wake up, capture all keystrokes to snare passwords and account numbers, and then send this information back to the hacker, who could then access the victim’s account as his leisure.

Masking the spammer’s identity

Spammers may incur the wrath of several hundred (or several million) irate victims. Some spam recipients respond with angry messages; others launch their own email bomb attacks, sending multiple messages to the spammer’s own address, clogging it and rendering it useless.

Unfortunately, crashing or clogging the spammer’s ISP can also punish innocent customers who happen to use the same service provider. To avoid such counterattacks, many spammers create temporary Internet accounts (on services such as Hotmail or Juno), send their spam, and then cancel the account before anyone can attack them. Getting kicked off an ISP and opening new accounts is just part of the game bulk emailers play. If someone actually wants to buy the spammer’s product, he can click a link in the spam message that will take him to the spammer’s website.

Of course, for those spammers who can’t be bothered to open and close email accounts, there’s an easier way. Many bulk emailing programs simply omit or forge the sender’s email address to avoid counterattacks.

Most ISPs limit the amount of email a single individual can send to avoid bandwidth hogs from impeding other customers’ Internet access. If an ISP catches someone sending out an inordinate amount of email, it can cancel the account. So, spammers may sign up for bulk emailing accounts, which are special mail servers that allow anyone to send massive amounts of email—for a price, of course.

Another alternative is the less expensive (and less ethical) method of sending spam through “zombie” computers, which have been previously hijacked by a worm or Trojan horse (see Chapter 5).

After infecting a network of computers with worms or Trojan horses, the hacker can control the infected or zombie computers with a program, called a bot, which may be stored on an IRC chat room. The hacker then rents out his network of infected computers to spammers, who send their spam to the controlling bot, which in turn distributes it through the zombie network. This has several advantages over other spamming methods for the unscrupulous bulk emailer.

First, since the spam appears to be coming from the email account of each individual zombie computer, or through each infected computer’s ISP’s mail server, tracing the spam to its source leads to an innocent person, not to the spammer himself. Second, by sending spam through a network controlled by a bot, known as a botnet, the spammer isn’t directly violating his ISP’s ban on bulk mailing. Third, and most importantly, many spam filters work by blocking messages from known bulk email accounts. When the spam comes from computers connected through different ISPs such as Earthlink, spam can often circumvent any filters people have installed. (If a filter detects massive amounts of email coming from a single ISP, the spam filter will block it. But if the email is coming from multiple ISPs, the filter often wrongly assumes the email is valid.)

Spammers can also hijack legitimate email accounts and use that account to flood the Internet with spam. Now if anyone traces the spam back to its source, they’ll find an innocent (and likely confused) person, while the real spammer has long since disappeared to hijack other email accounts to send spam through over and over again.

Protecting Yourself from Spammers

Now that you know how spammers find email addresses and send out spam, how can you fight back? Depending on your mood and temperament, your response may range from politeness to hostility. And you may never get any satisfactory response or resolution. But maybe you can vent some steam, at least.

Complain to the spammer

When you receive spam, the message may include an email address where you can request to have your address removed from the spammer’s list. Sometimes this works, but it’s more likely that this email address itself is phony, or that your reply simply alerts the spammer to the fact that yours is a valid email address, which might encourage him to sell your address to other spammers.

Complain to the spammer’s ISP

Even if you can’t find a valid return address in to the spammer’s message, you may still be able to uncover one elsewhere. To do so, search the spam’s header for the ISP’s address, such as earthlink.net, buried in the From field or Message-ID heading. Once you identify the ISP, you can complain directly to it.

For example, consider the following email:

Received: from flpvm07.prodigy.net by yipvme with SMTP; Mon, 28 Nov 2005 11:24:25 −0500

X-Originating-IP: [198.31.62.48]

Received: from mta.offer.omahasteaks.com (mta.offer.omahasteaks.com [198.31.62.48])

by flpvm07.prodigy.net (8.12.10 083104/8.12.10) with ESMTP id jASGNxvH018752

for <[email protected]>; Mon, 28 Nov 2005 08:24:07 −0800

X-MID: <[email protected]>

Date: Mon, 28 Nov 2005 11:24:24 −0500 (EST)

Message-Id: <[email protected]>

From: “Omaha Steaks” <[email protected]>

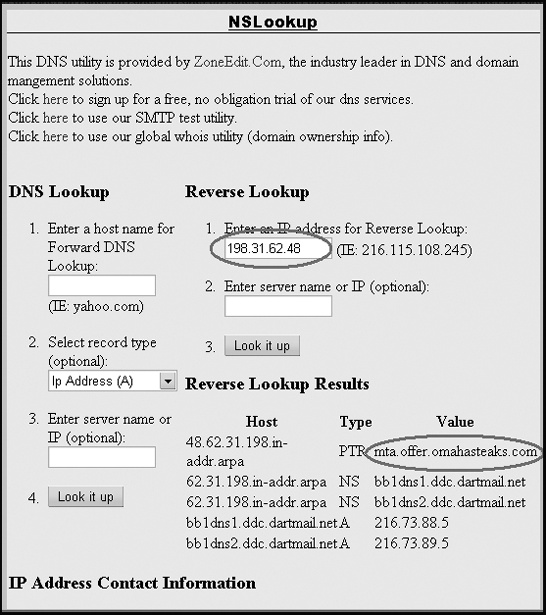

The “From” heading identifies the message as coming from [email protected], and the “X-Originating-IP” heading identifies the IP address of the sender as 198.31.62.48.

To verify that the IP address (omahasteaks.com) matches the numeric IP address shown in the X-Originating-IP heading, you need to do a reverse DNS lookup, using the tools on a site such as through ZoneEdit (www.zoneedit.com/lookup.html), as shown in Figure 18-3.

In this case, the numeric IP address matches the domain name, so the email probably hasn’t been forged. This means you should be able to contact the sender ([email protected]) directly and request to be removed from its list for future mailings. You could also try contacting the ISP used by the sender, which in Figure 18-3 is identified as DartMail.net. However, if you visit the DartMail.net site, you’ll find that it’s a service that specializes in mass emailing, so complaining to them about unwanted spam won’t get you very far.

In this next message example, the email address ([email protected]), which looks like it’s from a site in Spain, appears to be forged. A reverse DNS lookup of the IP address identified by the X-Originating-IP heading reveals that 69.61.230.16 belongs to Fuse.Net, which is a Cincinnati-based ISP. Since the email address is phony, you can’t complain directly to the spammer but you can complain to what appears to be his ISP, Fuse.Net.

Received: from flpvm21.prodigy.net by mailapps2 with SMTP; Tue, 22 Nov 2005 11:47:22 −0500

X-Originating-IP: [69.61.230.16]

Received: from cn-esr1-69-61-230-16.fuse.net (CN-ESR1-69-61-230-16.fuse.net [69.61.230.16])

by flpvm21.prodigy.net (8.12.10 083104/8.12.10) with SMTP id jAMGi3Ir025787;

Tue, 22 Nov 2005 08:44:04 −0800

Received: (from tomcat@localhost)

by 82.51.63.111 (8.12.8/8.12.8/Submit) id j0CHmn4V425775

for [email protected]; Tue, 22 Nov 2005 08:46:29 −0800

Message-ID: <[email protected]>

Date: Tue, 22 Nov 2005 08:46:29 −0800

From: “sileas Workman” <[email protected]>

ISPs can’t monitor all of their users, but if they receive a flood of complaints about one particular customer, they can take action against the spammer and stop future abuses (maybe).

To notify an ISP of a spammer, email your complaint to [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], or [email protected], where spammer.site is the site from which the spammer sent the junk email.

Not all spammers use bulk emailing services or botnets to mask their identity, so complaining to the spammer’s ISP might actually get the spammer kicked off.

Complain to the Internal Revenue Service

Because many spammers promote get-rich-quick schemes, there’s a good chance they don’t keep proper tax records of their earnings. So one way to take revenge on these spammers is to contact the Internal Revenue Service (or your own government’s tax agency) to investigate. American citizens can forward spam either to [email protected] to report fraudulent make-money-fast (MMF) schemes or to [email protected] to report tax evaders. Reports of tax fraud should be sent directly to your regional IRS Service Center, for which there is currently no Internet email address for reporting suspected offenses.

To avoid getting caught by their government’s tax agency, many spammers make their physical location hard to find. They may live in one country but host their website in another. And it’s hard to tell for sure who actually owns the website, especially if the spammer uses a free web hosting service such as Geocities or Tripod. With electronic payment transfers, spammers can live anywhere in the world and collect money from their websites, regardless of where they’re hosted. This can make tracking them down to pay income taxes nearly impossible. But hey, you’ve gotten it off your chest anyway, right?

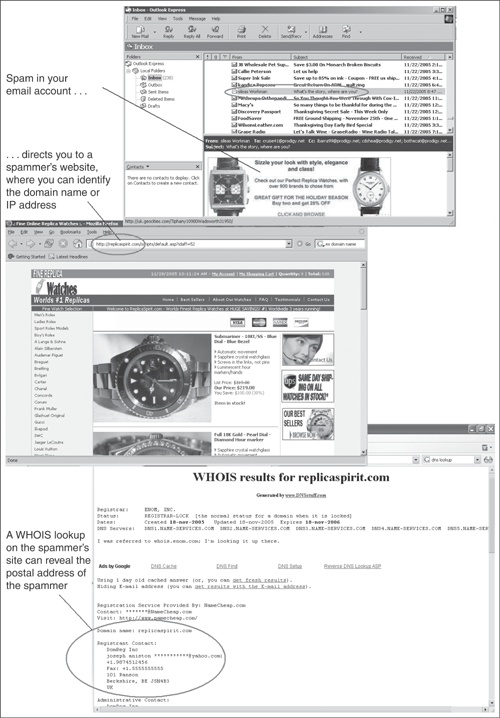

Locating the spammer’s postal address

Once you know the IP address or domain name of a spammer’s website, you can do a WHOIS lookup using a service such as DNS Stuff (www.dnsstuff.com). This will tell you the name of the company or person who registered the IP address or domain name, as shown in Figure 18-4.

Unfortunately, spammers know that their websites will become targets so they often disguise their real site address through a third-party server, such as a specialized bulk email ISP. One such ISP even advertises the following:

IP Tunneling is a method where the recipient of your email message accesses your website through a (non traceable) binary encrypted link similar in appearance to the following:

(.....unique.site.net .co.fr |https.am2002.opt.com:8096)

Once the recipient clicks the email message, their browser references our servers through the binary encoding within the link. Our servers (behind the scenes) then call upon your web site’s IP which resides either on your server or a 3rd party’s server. This technology provides its users with COMPLETE protection and anonymity.

As a result, it’s possible to browse a spammer’s website without ever knowing the exact domain address that you can use to look up the spammer’s real address and telephone number.

How Spam Filters Work

Spam filters can reduce, but not eliminate, spam. Many ISPs now run spam filters to weed out the most obvious offenders, but you may still want your own filter to catch any additional spam that slips through. Common techniques that spam filters use include content filtering (also called Bayesian filtering), blacklists and whitelists, DNS lookups, and attachment filtering.

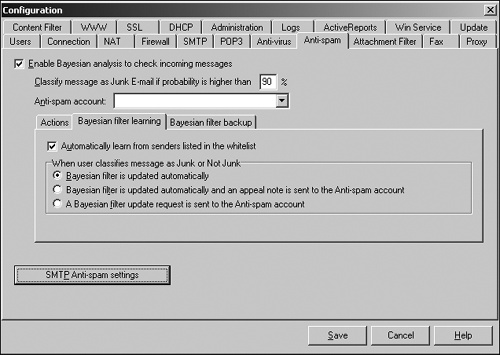

Content (Bayesian) filtering

Content filtering is the most common type of spam filtering. It works by analyzing the text in each message using probability theory developed by the mathematician Thomas Bayes. Most spam can be readily identified by subject and text headings like “!!!MAKE MONEY FAST!!!” However, other types of spam can be more subtle.

If you identify any spam messages that slip past the filter, the program can gradually “learn” and get better at sifting through similar spam in the future, as shown in Figure 18-5. Because spammers constantly change their tactics, you’re always going to get some spam, but content filtering can gradually reduce a potential flood to a mere trickle.

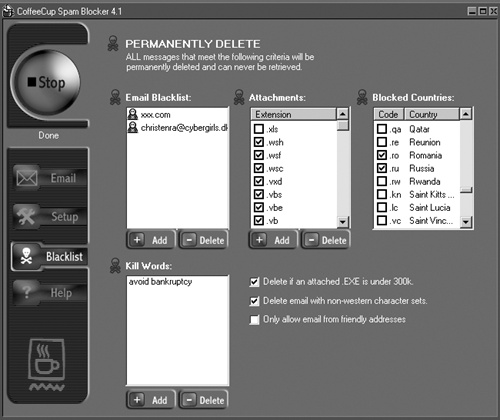

Blacklists and whitelists

Another filtering technique involves blacklists or whitelists, or both. A blacklist is simply a list of known spammer email addresses or domains, including domains of entire countries (because many spammers route spam through mail servers located in Russia or Romania), as shown in Figure 18-6. The moment the filter recognizes that a message has come in from a known spammer, it blocks the message.

Blacklists can supplement content filtering, but are easily fooled by themselves because spammers change email addresses so often. As a result, some filters also use whitelists.

A whitelist defines acceptable email addresses. If the filter receives email from anyone on its whitelist, the email may pass freely. All others will be rejected. In many cases, the filter will respond to any rejected email address, requesting that the user resend the message to a specific address or using a specific code. Any person sending legitimate email will have no trouble with this, but a spammer isn’t likely to take the time to read and follow these additional instructions.

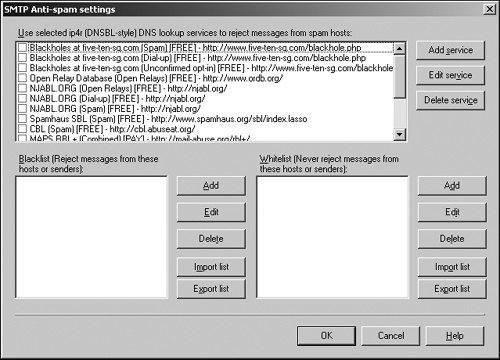

DNS lookup lists

Several organizations, such as SpamCop (www.spamcop.net) and ORDB (Open Relay DataBase)—www.ordb.org, maintain lists of known spam sources. To get their information, the maintainers of these lists deliberately solicit spam for analysis. To supplement its list of known spam sources, SpamCop creates lists of bogus email addresses that nobody uses, which they post on web pages. When spammers harvest these bogus email addresses and try to use them, SpamCop immediately recognizes them as spam.

Many mail servers on the Internet don’t accurately record where email comes from, either through negligence or deliberate intent (such as special bulk mailing services). These types of mail servers are known as Open Relays, and because spammers tend to use these to mask their own email addresses, DNS lookup lists record known open relay servers and either reject any messages sent from them outright or scrutinize messages from these servers extra carefully to weed out spam, as shown in Figure 18-7.

Attachment filtering

Many spammers send their entire message as a graphic image that can’t be read by content filters. In response, some spam filters include attachment filters that look for email messages containing nothing but graphic images. Of course, these attachment filters can’t identify the visual content of a graphic image, but, when combined with other filtering techniques, they can flag suspicious messages.

Attachment filtering can also help prevent infection by screening out .exe (executable), .wsh (Windows Script Host), or .vbs (Visual Basic Script) files that could contain viruses, worms, or Trojan horses.

Stopping Spam

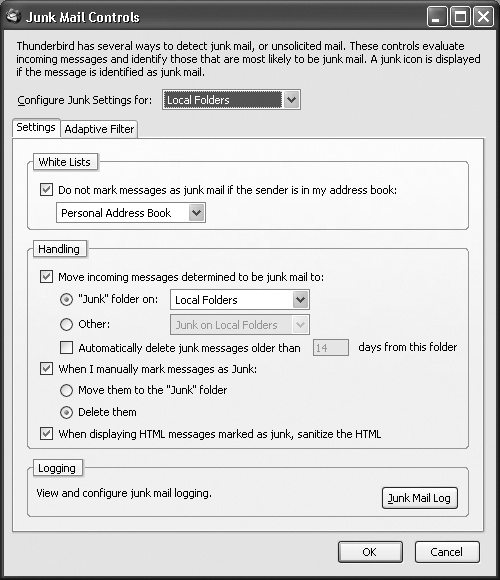

You can never completely stop spam, but you can eliminate much of it. First, find out whether your ISP offers a spam filter, and if so, then turn it on. If your ISP’s spam filters don’t seem terribly effective, consider switching your email account to a special filtering service such as SpamCop (www.spamcop.net) or Aristotle Internet Access (www.aristotle.net/business-services/email-filtering). These services screen your email for spam and route suspicious messages to a designated location where you can review them before downloading.

For a second layer of defense, turn on filtering in your email client program, such as Microsoft Outlook or Mozilla Thunderbird, as shown in Figure 18-8. Email programs often allow you to automatically route suspected spam into a designated junk or spam folder where you can more safely review it before deleting it.

Finally, consider getting a separate spam-filtering program such as SpamBuster (www.contactplus.com), SpamButcher (www.spambutcher.com), CoffeeCup Spam Blocker (www.coffeecup.com), or SpamKiller (www.mcafee.com). These programs can also flag potential spam so your email program routes it to a special junk folder or just deletes it altogether.

To reduce the chances of receiving spam in the first place, give out your email address only sparingly. Create a separate account with a free service such as Hotmail to use for posting messages in Usenet newsgroups, registering at websites, or making online purchases (many companies sell your email address when you sign up with them). By creating a decoy email account, you can redirect spam to accounts that you rarely use and keep your everyday email account free of the most annoying spam.

Note

When using multiple spam filters, make sure you always have a way to retrieve any messages that the spam filters weed out since there’s always a chance that a legitimate message might get caught in a spam filter by mistake.

Possible future solutions to spam

Many people are engaged in developing ways to stop spam entirely. One idea proposed by Bill Gates is to force everyone to buy “postage” to send email. This postage wouldn’t cost money in the traditional sense. Instead, it would require the sending computer to calculate a mathematical problem, temporarily tying up its resources. It would cost the sending computer a trivial amount of time and resources for regular emailing, but it could cripple the spammer who wants to send 10,000 email messages at once.

Some Internet service providers are proposing to stamp outgoing messages with a digital signature of the customer’s domain name, using strong encryption so no one could alter or forge it. One of the first implementations of this idea has come from Yahoo! (http://antispam.yahoo.com/domainkeys) and its open-source program DomainKeys, which verifies the domain of email senders. If someone tries to forge an email address, DomainKeys will automatically flag the message as spam.

Forcing computers to pay “postage” or reveal their true email address through encryption might work, but only if the entire structure of the Internet changes to adapt these practices en masse. Until then, spammers will continue flooding the Internet with advertisements while everyone tries to agree on a solution.

Microsoft is currently testing a unique email filter called SNARF (Social Network and Relationship Finder). SNARF doesn’t analyze content. It works by analyzing to whom you send email and from whom you receive it. The idea is that you’re more likely to want email from people you’ve contacted before, and that email from unknown addresses is more likely to be spam. To grab a copy of SNARF, visit Microsoft Research (http://research.microsoft.com/community/snarf).

Going on the offensive

Filtering will never stop spam, so some people prefer to go on the offensive and attack spammers directly. In 2004, Lycos Europe distributed a special screensaver called Make Love Not Spam, as shown in Figure 18-9.

When a computer was idle, the Make Love Not Spam screensaver would kick in and request to view a known spammer’s website. If enough screensavers sent their requests at the same time, the spam website would become slow and overloaded, either making it inconvenient for legitimate users to purchase the spammer’s products or denying them access altogether.

Shortly after the Make Love Not Spam screensaver appeared, however, Lycos Europe killed the project. Public outcry over a commercial organization using a denial of service attack created too much controversy. Still, it shows that corporations are not above using hacker techniques and that the real future of hacking might lie within the payroll of a corporation.

IBM has developed a similar tactic for its FairUCE (www.alphaworks.ibm.com/tech/fairuce) spam filter. Unlike traditional filters that examine a message’s content to identify spam, FairUCE analyzes email to determine where the message might have been sent from, despite forged email addresses and spoofed headers that mask its true source. Instead of trying to identify the spammer’s email address, FairUCE tries to identify the domain that sent the spam in the first place. Then, it bounces the spam back to the sending domain in an attempt to slow it down and prevent it from sending more spam.

Another tool in the fight against spam, the OptOutByDomain (www.OptOutByDomain.com) site, lets you tell spammers which domains you don’t want them to spam, rather than listing one email address at a time. Under the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003, spammers must legally comply with such a request or they can get sued, which is what OptOutDomain’s companion site, SueASpammer (www.sueaspammer.com) is all about, as shown in Figure 18-10.

Antispam organizations

Despite laws, threats, and physical action against it, spamming is so cost-effective that it’s probably here to stay. If spam really irritates you, consider joining and supporting the Coalition Against Unsolicited Commercial Email (CAUCE)—www.cauce.org—an organization consisting of Internet users who have banded together to lobby for new laws to regulate unsolicited email.

To show you how influential one person can be in the fight against spam, visit Netizens Against Gratuitous Spamming (www.nags.org). This website shares tips for identifying and dealing with spam and offers an example of chaff, which is garbage data designed to fool spammers who retrieve email addresses from websites.

To keep up with the latest news regarding spam and to learn more about how to defeat spam, visit Death to Spam (www.mindworkshop.com/alchemy/nospam.html), Spam News (www.spamnews.com), Junk Busters (www.junkbusters.com), Fight Spam (http://spam.abuse.net/spam), and The Spamhaus Project (www.spamhaus.org).

No matter how assiduously you protect your email address or run filters, you’re going to get spammed, so it’s nice to know that at least you have allies on the Internet who want to help you trace, identify, and stop spam as much as humanly possible.

A PostScript: Spam as Propaganda

Spam is hard to stop, which makes it a useful tool for spreading messages across the Internet. In December 2005, a neo-Nazi sympathizer reportedly created a variant of the Sober worm modified to send spam containing phrases like “Multicultural = multicriminal.” The messages also included links to racist German websites and news articles that support anti-immigrant views.

One Chinese dissident group that publishes a newsletter called VIP Reference (www.bignews.org) has found another use for spam. Because Chinese citizens can’t access certain websites without fear of government retribution, VIP Reference floods Chinese computers with spam containing its pro-democracy newsletter. Now Chinese citizens can read censored information without being guilty of soliciting it themselves. So the next time you’re cursing the spam flooding your email account, it might comfort you to think about how spam is helping Chinese citizens read censored information. Maybe spam could become less of a dirty word if it were used to promote ideas like democracy and freedom, instead of Viagra and pornography.