Chapter 2. The First Hackers: The Phone Phreakers

creator of self-improvement program Psycho-Cybernetics

We find no real satisfaction or happiness in life without obstacles to conquer and goals to achieve.

The first phone phreakers were teenage boys.

That fact alone isn’t too surprising, until you realize that those first hackers appeared in 1878, when teenage boys worked as telephone operators for the fledgling Bell Telephone network. Hiring teenage boys seemed logical; telegraph offices often hired them to work similar jobs as telegraph delivery messengers. Putting teenage boys in charge of the telephone network made good sense right up until they started randomly mixing telephone lines to connect total strangers as a prank and started talking back to customers and interfering in their conversations just for laughs.

Bell Telephone quickly replaced its prepubescent male operators with more dependable women. Still, the spirit of playfulness that first surfaced among those teenagers would soon reappear to haunt the telephone networks again.

When the telephone company replaced human operators with automated electronic switching systems (ESSs) in the 1960s, the telephone hackers (also known by their more colorful nickname, phone phreakers) found new opportunities to toy with the telephone system.

You couldn’t always trick a human operator into granting you free phone calls, but you could trick the telephone network’s automated switching systems into doing so. With nothing but primitive computers routing telephone calls around the country, phone phreakers quickly learned that if you knew the right signals, you could get the telephone system to do anything from granting free long-distance telephone calls to letting you connect multiple phone lines to form conference calls—all without the telephone company’s knowledge.

A Short History of Phone Phreaking

Unlike computer hacking, which can often be practiced in isolation on a single personal computer, phone phreaking was pretty complicated and thus required more extensive preparation. You might be reprogramming the phone company’s computers one moment, soldering wires together to alter a pay phone the next, and then chatting with a telephone employee to get the passwords for a different part of the phone system. Like computer hacking, phone phreaking is an intellectual game in which players try to learn as much as they can about the system (usually) without getting caught.

Perhaps the most famous phone phreaker is John Draper (www.webcrunchers.com/crunch), nicknamed Captain Crunch because of his accidental discovery of a unique use for a toy whistle found in a box of Cap’n Crunch cereal. He found that blowing this toy whistle into his phone’s mouthpiece emitted a 2600Hz tone, the exact frequency used to instruct the telephone company’s switching systems to make free telephone calls.

Others soon discovered this secret, and some even developed the ability to whistle a perfect 2600Hz tone. For those unable to obtain the original Cap’n Crunch toy whistle, entrepreneurs began selling devices known as blue boxes that emitted the 2600Hz tone and other telephone company signal tones. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, the founders of Apple Computer, even sold blue boxes to college students so they could make free phone calls from their dormitories.

Blue boxes worked as long as the telephone company relied on their old electromechanical switching systems. But eventually these were replaced with newer electronic switching systems (ESSs), which rendered blue boxes (and the infamous 2600Hz tone) useless (although blue boxes may still work on older phone systems outside the United States).

Of course, ESSs brought with them a whole new set of problems. With the older electromechanical switching systems, a technician had to physically manipulate switches and wires to modify the switching system. With an ESS, technicians could alter the switching system remotely over the phone lines.

If a technician could perform this magic over the telephone, however, phone phreakers could do the same—if they knew the proper codes and procedures. Obviously, the telephone company wanted to keep this information secret, but the phone phreakers wanted to let everyone know how the telephone system worked (which is partly what the ongoing struggle between the telephone company and phone phreakers is all about).

Note

To learn more about phone phreaking, visit Hack Canada (www.hackcanada.com) or Phone Losers of America (www.phonelosers.org). Or try the alt.phreaking and alt.2600.phreakz newsgroups for messages about phreaking.

Phone Phreaking Urban Legends

If you have a telephone, anyone in the world, including the legions of phone phreakers just goofing around with the telephone system, can call you. Steve Wozniak reportedly once called the Vatican and pretended to be Henry Kissinger. Other phone phreakers have attempted to call the Kremlin via the White House hotline and have rerouted a prominent TV evangelist’s business number to a 1-900 sex line.

Because a large part of phone phreaking lore involves performing progressively more outrageous acts and then boasting about them, the following phone phreaking stories may or may not be true. Nevertheless, they will give you an idea of what phone phreakers can achieve given the right information. (These are “urban myths” circulating on the Internet and are reprinted here with minor editing for the sake of clarity and explanation.)

The toilet paper crisis in Los Angeles

Part of the thrill of phone phreaking is discovering areas of the telephone network that the general public wouldn’t normally access. In the early ’70s, two phone phreakers discovered an unlisted phone number that only a handful of people had the right to know about. They decided to use it to make the ultimate prank phone call. What follows is an edited version of the firsthand account of one of the phreakers.

[At the time of the prank,] it was really easy for phone phreakers to pop into the phone company’s AutoVerify trunks. This procedure is used when someone legitimately needs to break in on a busy phone line. Ordinarily, it goes like this:

The operator selects a special trunk (phone line), class marked (reserved) for this service, and dials either the last five digits of the phone number, or a special Terminating Toll Center (TTC) code like 052, followed by the entire seven-digit number. After that, the operator hears scrambled conversation on the line. The parties talking hear nothing, not even a click.

Next, the operator “flashes forward” by causing the equipment to send a tone burst at 2600Hz, which makes a three-way connection and places a beep tone on the line so that both original parties can hear the click (flash, in this case) followed by a high-pitched beep. At this point, the parties can hear the operator and vice versa. In the case of a legitimate interruption, the operator announces that there is an emergency and the line should be released. This service is available today for a $2 fee ($1 in certain areas).

Earlier, I had mapped every 800 number that terminated in Washington, DC, by scanning the entire 800-424 prefix. That scan found an impressive quantity of juicy numbers that allowed free access to Congressional phone lines, special White House access numbers, and so on.

While scanning 800-424, I got this dude whose bad attitude caught my attention. I was determined to find out who he was. I called back and said, “This is White Plains tandem office for AT&T, which subscriber have we reached?”

This person said, “This is the White House CIA crisis hotline!”

“Oh!” I said, “We’re having a problem with crossed lines. Now that I know who this is, I can fix it. Thank you for your time—good-bye!”

I had a very special 800 number.

Eventually my friends and I had one of our info-exchanging binges, and I mentioned this incident to them. One friend wanted to dial it immediately, but I persuaded him to wait. I wanted to pop up on the line, using AutoVerify to hear the conversation.

But first we needed to determine which exchange this number terminated in, because AutoVerify didn’t know about 800 numbers.

At the time, all 800 numbers had a one-to-one relation between prefix and area code. For instance, 800-424 = 202-xxx, where xxx was the three-digit exchange determined by the last four digits. In this case, 800-424-9337 mapped to 202-227-9337. The 227 (which could be wrong) was a special White House prefix used for faxes, telexes, and, in this case, the CIA crisis line.

Next we got into the class marked trunk (which had a different sounding chirp when seized) and MF’ed KP-054-227-9337-ST into this special class marked trunk. (“MF” stands for multi-frequency, the method by which the phone phreakers sent the specific code into the telephone trunk.) Immediately we heard the connection tone and put it up on the speaker so we would know when a call came in.

Several hours later, a call came in. It appeared to have CIA-related talk, and the code name “Olympus” was used to summon the president. I had been in another part of the building and rushed into the room just in time to hear the tail end of the conversation.

We had the code word that would summon Nixon to the phone. Almost immediately, another friend started to dial the number. I stopped him and recommended that he stack at least four tandems (switches connecting different lines or trunks of the telephone network) before looping the call to the White House. (Stacking tandems means routing a phone call between different switches, making it harder for anyone to trace exactly which phone number you’re calling from. After routing a phone call through multiple switches, looping connects the caller to the desired phone number.)

Sure enough, the man at the other end said “9337.”

My other friend said, “Olympus, please!”

The man at the other end said, “One moment, sir!” About a minute later, a man that sounded remarkably like Nixon said, “What’s going on?”

My friend said, “We have a crisis here in Los Angeles!”

Nixon said, “What’s the nature of the crisis?”

My friend said in a serious tone of voice, “We’re out of toilet paper, sir!”

Nixon said, “WHO IS THIS?”

My friend then hung up. We never did learn what happened to that tape, but I think this was one of the funniest pranks.

To the best of my recollection, this was about four months before Nixon resigned because of the Watergate crisis.

The Santa Barbara nuclear hoax

Making crank calls can be fun, and it’s a bigger rush as you fool more and more people. However, as the two phone phreakers in the following example found out, sometimes a crank call can go a little bit too far . . .

Two Southern Californian phone phreakers once tied up every long-distance line coming into Santa Barbara using two side-by-side phone booths on the beach and some very simple phone phreaking equipment. When people tried to call into Santa Barbara, their calls were rerouted to the two phreakers, who told all callers that a mysterious explosion had wiped out the city.

The first call was from a mother to her son, a student at the University of California, Santa Barbara campus. The two phreakers told the woman that they were with the National Guard Emergency Communications Center and that there was no longer any University of California at Santa Barbara. In breathless tones they said the campus and, in fact, the entire city of Santa Barbara had been wiped out in a freakish nuclear accident; a “nuclear meltdown,” they told her. She was politely asked to hang up in order to clear the line for emergency phone calls.

A few minutes later the horrified mother called back, this time with operator assistance. The phone phreakers calmly repeated their story to the operator, asked her not to place calls to Santa Barbara, and told her not to worry.

Within minutes, newspaper and television reporters, FBI agents, and police officers began calling from all over the country. Hundreds of anxious people who had heard about the “meltdown” phoned to check on relatives and friends. The phreakers told the callers that they had reached the National Guard base 50 miles away from the disaster site and that they were tied into emergency circuits. After about an hour the two phreakers became frightened by the chaos they were causing and restored the phone system to normal. They were never caught.

The next day, the Los Angeles Times carried a short news article headlined “Nuclear hoax in Santa Barbara.” The text explained how authorities were freaked out and how puzzled they were. The phone company commented, “We don’t really know how this happened, but it cleared right up!”

The president’s secret

Phone phreakers don’t necessarily abuse their power over the telephone system; they just want to explore every part of the phone network and understand how it operates. But as this phone phreaker discovered, sometimes certain phone numbers are best left alone.

Some years back, a telephone fanatic in the Northwest made an interesting discovery about the 804 area code (Virginia). He found that the 840 exchange in the 804 area code did something strange. In calling every 804-840-xxxx phone number but one, he would get a recording as if the exchange didn’t exist. However, if he dialed 804-840 followed by four rather predictable numbers (like 1-2-3-4), he got a ring!

After one or two rings, somebody picked up. Because he was experienced with this kind of thing, he could tell that the call didn’t “supe,” that is, no charges were being incurred for calling this number. (Calls that get you to an error message or a special operator generally don’t “supe,” or supervise.) A female voice with a hint of a southern accent said, “Operator, can I help you?”

“Yes,” he said, “What number have I reached?”

“What number did you dial, sir?”

He made up a number that was similar.

“I’m sorry. That is not the number you reached.” Click.

He was fascinated. What in the world was this? He knew he was going to call back, but before he did, he tried some more experiments. He tried the 840 exchange in several other area codes. In some, it came up as a valid exchange. In others, exactly the same thing happened—the same last four digits, the same southern belle.

He later noticed that the area codes where the number functioned properly formed a beeline from Washington, DC, to Pittsburgh, PA. He called back from a pay phone.

“Operator, can I help you?”

“Yes, this is the phone company. I’m testing this line and we don’t seem to have an identification on your circuit. What office is this, please?”

“What number are you trying to reach?”

“I’m not trying to reach any number. I’m trying to identify this circuit.”

“I’m sorry, I can’t help you.”

“Ma’am, if I don’t get an ID on this line, I’ll have to disconnect it. We show no record of it here.”

“Hold on a moment, sir.”

After about a minute, she came back. “Sir, I can have someone speak to you. Would you give me your number, please?”

He had anticipated this and had the pay phone number ready. After he gave it, she said, “Mr. XXX will get right back to you.”

“Thanks.” He hung up the phone. It rang. Instantly. “Oh my God,” he thought, “They weren’t asking for my number—they were confirming it!”

“Hello,” he said, trying to sound authoritative.

“This is Mr. XXX. Did you just make an inquiry to my office concerning a phone number?”

“Yes. I need an identi- . . .”

“What you need is advice. Don’t ever call that number again. Forget you ever knew it.”

At this point my friend got so nervous, he immediately hung up. He expected to hear the phone ring again, but it didn’t.

Over the next few days, he racked his brain trying to figure out what the number was. He knew it was something big—so big that the number was programmed into every central office in the country. He knew this because if he tried to dial any other number in that exchange, he’d get a local error message, as if the exchange didn’t exist.

It finally came to him. He had an uncle who worked for a federal agency. If, as he suspected, this was government-related, his uncle could probably find out what it was. He asked the next day and his uncle promised to look into it.

When they met again, his uncle was livid. He was trembling. “Where did you get that number?” he shouted. “Do you know I almost got fired for asking about it? They kept wanting to know where I got it!”

Our friend couldn’t contain his excitement. “What is it?” he pleaded. “What’s the number?”

“IT’S THE PRESIDENT’S BOMB SHELTER!”

He never called the number again after that. He knew that he could probably cause quite a bit of excitement by calling the number and saying something like, “The weather’s not good in Washington. We’re coming over for a visit.” But my friend was smart. He knew that there were some things that were better left unsaid and undone.

True and Verified Phone Phreaking Stories

The previous phone phreaking stories may be more fiction than fact. However, the following tales are true, and perhaps more frightening than anything anyone could ever make up.

Making free phone calls, courtesy of the Israeli Army

The Israeli Army is considered the best in the world; even its radio stations enjoy round-the-clock protection provided by armed soldiers patrolling the perimeters. But those radio stations aren’t safe from phone phreakers. Armed guards and barbed wire mean nothing to someone who can probe a network through the telephone lines. And as blind phone phreaker Munther “Ramy” Badir explains, an army outpost has phone lines that cannot be tapped by the police, so there is no monitoring. “These are the safest lines on which to do something.”

In 1993, Ramy and his two brothers Muzher and Shadde Badir, all completely blind since birth, drew the attention of authorities when they broke into Bezeq International, Israel’s largest telecommunications provider. After hacking Bezeq’s phone networks and giving themselves calling privileges, the Badir brothers made a deal to direct phone calls to a Dominican Republic phone sex service and get paid for each call. (Visit any hacker website and you’ll see it’s common to direct visitors to sex services as a money-making scheme.)

To ensure that they would get paid as much as possible, the Badir brothers made phone calls to the Dominican Republican sex service themselves, billing their phone calls to companies such as Nortel and Comverse. When a Bezeq International anti-fraud engineer discovered the lines the Badir brothers were using and blocked them, the brothers simply called Bezeq International, impersonated the anti-fraud engineer’s voice, and ordered the lines unblocked.

Next the brothers attacked an Israeli phone sex service and talked the secretary into revealing her boss’s computer password. Armed with this information, they hacked into the phone sex service’s computers and made off with 20,000 customer credit card numbers. When the sex service’s boss confronted them, they retaliated by programming all his telephones to ring continuously, with no one on the line.

According to authorities, the Badir brothers next broke into an Israeli Army radio station’s phone system and activated a function called Direct Inward Systems Access (DISA). Not only did this allow multiple people to share a single telephone line, but it also enabled anyone to place long-distance phone calls that would be charged to the Israeli Army radio station.

Next, the brothers sold access to the hacked phone system so that anyone could make free phone calls from their home, cloned cell phones, or phone kiosks set up along the Gaza Strip. As Israeli authorities closed in on them, the brothers fought back by taking down the police phone systems, crashing their computers, and even eavesdropping on their telephone calls.

When Israeli police finally raided the Badir brothers’ home, they found nothing more incriminating than an ordinary laptop computer. “It’s all in our heads,” Ramy said. “The police took my laptop, which contained programs for running through thousands of numbers very quickly, but I had it designed to erase everything on the hard drive if it was opened by somebody other than me. They lost all the material.”

Between 1999 and 2004, Ramy ultimately spent a little more than four years in prison and his brothers served community service and a suspended sentence. Like many reformed hackers, Ramy insists that he’s now going to work in security. “I am inventing a PBX firewall. I know all the weakest spots of a telephone system. I can protect any system from infiltration. I am going to the other side, coming up with devices that will keep the phreakers out.”

Phone phreaking for escorts in Las Vegas

While most phone phreakers use their skills to make free phone calls or to toy around with the telephone system, some have used their skills to help organized crime syndicates reroute phone calls around Las Vegas.

If you’ve ever walked along the Las Vegas Strip, you’ve been bombarded by people handing out flyers and brochures for all types of in-room adult entertainment services. Vending machines bolted to the sidewalks also freely dispense similar pornographic “reading” material, showing bodies, names, and telephone numbers. With such an abundance of pornographic material within reach of any passerby, you’d think that these escort services would be inundated with phone calls from lonely visitors holed up in hotel rooms across the city.

In the old days, that was true. Nowadays, though, despite the abundance of advertising, these adult entertainment businesses are lucky to get one or two calls a night, and, inevitably, these calls come from people who are either outside of Las Vegas or calling from a pay phone or cell phone. These phone calls aren’t routed through the big casino/hotel switchboards in Las Vegas. If anyone tries to call these services from the telephone in a Las Vegas hotel room, the calls either don’t connect or are mysteriously rerouted to a rival adult entertainment service (presumably controlled by organized crime). Naturally, most callers aren’t aware that their phone call went to a different service provider than the one they called, since they wind up getting a woman to come to their room anyway.

Sometimes the phone calls aren’t rerouted but are traced instead. So when a caller reaches an adult entertainment service, a rival service that’s tracing the phone line sends a girl to the customer first. By the time the girl from the intended adult service shows up, the customer is already being serviced by the competition’s girl.

The next time you’re in Las Vegas, pick up a brochure for an adult entertainment business off the Strip and call using your hotel room telephone. Spend the next 10 or 15 minutes asking questions and then hang up without asking for a girl. If a rival adult service has been tracing your call, a girl should show up at your hotel room within 15 minutes anyway, asking, “Did you call for an entertainer?” Ask the girl what service she came from and she’ll likely respond with a noncommittal answer such as, “Which service did you call? I work for several of them.”

Then again, you might want to avoid this experiment altogether, since wasting the time (and money) of those in organized crime is rarely a healthy decision.

Phone Phreaking Tools and Techniques

The goal of every phone phreaker is to learn more about the telephone system, preferably without paying for any phone calls in the process. Whether they access the telephone system from an appliance inside their own home, a public pay phone, or someone else’s “borrowed” (stolen) phone line, phone phreakers have found a variety of ways to avoid paying for their phone calls.

Shoulder surfing

The crudest level of phreaking is known as shoulder surfing, which is simply looking over another person’s shoulder as they punch in their telephone calling card number at a public pay phone.

The prime locations for shoulder surfing are airports, where travelers are more likely to use calling cards than change to make a call. Given the hectic nature of a typical airport, few people take notice of someone peering over their shoulder while they punch in their calling card number, or listening in as they give it to an operator.

Once you have another person’s calling card number, you can charge as many calls as you like until the victim receives the next billing statement and notices your mysterious phone calls. Of course, once the victim notifies the phone company, that calling card number is usually canceled. (Since shoulder surfing involves stealing from individuals, true phone phreakers look down on it as an activity unworthy of anyone but common thieves and juvenile delinquents. True phone pheakers only believe in stealing service from the telephone company, and even then they don’t feel that they’re actually causing any harm or costing the company any money.)

As more people rely on cell phones and fewer on pay phones and calling cards, shoulder surfing is a dying art, but it can still be a handy technique for stealing a password or PIN from someone using a computer or automated teller machine.

Phone phreaking with color boxes

Another way to avoid paying for phone calls is to trick the phone company into thinking either that you already paid for them or that you never made them in the first place. To physically manipulate the phone networks, phone phreakers trick the telephone system through telephone color boxes, which either emit special tones or physically alter the wiring on the phone line.

Although the Internet abounds with instructions and plans for building various telephone color boxes, many of the older ones, such as blue boxes, no longer work with today’s phone systems in the United States—although they might still work in other countries, particularly Third World nations where old technology has been redeployed.

Here are some descriptions of various color boxes that others have made and used. But first, a warning from a phone phreaker regarding the legality of building and using such boxes:

You have received this information courtesy of neXus. We do not claim to be hackers, phreaks, pirates, traitors, etc. We only believe that an alternative to making certain info/ideas illegal as a means to keep people from doing bad things - is make information free, and educate people how to handle free information responsibly. Please think and act responsibly. Don’t get cockey, don’t get pushy. There is always gonna be someone out there that can kick your ass. Remember that.

Blue box

The blue box, the first of the telephone color boxes, reportedly got its name because the first one confiscated by police just happened to be blue. To use a blue box, phone phreakers would dial a phone number to connect to the telephone network and then turn on the box to emit its 2600Hz tone. This tricked the telephone system into thinking that they had hung up. Then the phone phreaker could either whistle different tones or use additional color boxes to emit tones that would dial an actual phone number. Since the blue box had already tricked the telephone system into thinking the caller had hung up, the subsequent calls made would not be charged.

Red box

When you insert a coin into a pay phone, it triggers a relay that emits a tone specific to that coin (a nickel makes a different sound than a dime or a quarter). A red box simulates the sound of money dropping into a pay phone. The telephone system listens to all the tones emitted to determine how much money has been deposited. When the total amount deposited equals the amount needed to make a phone call, the telephone system connects the pay phone to the network.

Green box

A green box generates three tones that can control a pay phone: coin collect (CC), coin return (CR), and ringback (RB). What happens is that one phone phreaker uses an ordinary pay phone to call a phone phreaker who has a green box attached to his phone. The phone phreaker receiving the call can activate the green box to send the coin collect (CC) tone (to trick the pay phone into thinking the phone phreaker dropped money into the pay phone), the coin return (CR) tone (to force the pay phone to spit coins into its return slot), or the ringback (RB) tone (to cause the green box phone to call the pay phone, allowing the phone phreaker at the pay phone to receive a phone call and talk to the other person free of charge).

Black box

Unlike blue boxes or red boxes, which prevent you from being charged for making calls, a black box prevents other people from being charged when they call you.

A black box works by controlling the voltage on your phone line. Before you receive a phone call, the voltage is zero. It jumps to 48V, however, the moment the phone rings. As soon as you pick up the phone, it drops back down to 10V, and the phone company begins billing the calling party.

A black box keeps the voltage on your phone line at a steady 36V so that it never drops low enough to signal the phone company to start billing. As far as the telephone company can tell, your phone keeps ringing because you haven’t answered it yet, even while you’re chatting happily with your friends. (Black box calls should be kept short, however, because the telephone company may get suspicious if your phone keeps “ringing” for a long period of time without the caller hanging up.)

Silver box

A silver box modifies your phone to generate four special tones designated “A”—Flash, “B”—Flash Override Priority, “C”—Priority Communication, and “D”—Priority Overide (Top Military). Although the telephone company has never designated any official use for these extra tones, that hasn’t stopped phone phreakers from experimenting with them. For example, phone phreakers discovered that if you generated the “D” tone and pressed 6 or 7, you could reach loop ends, which are two phone numbers that the telephone company uses to test connections. If two phone phreakers accessed these loop ends at the same time, they could make free phone calls to each other.

Phone phreaking with color box programs

Making a telephone color box often involved soldering or connecting wires, resistors, and capacitors together. But with the advent of personal computers, people found they could write programs to mimic different telephone color boxes. By running these programs on a laptop or handheld computer and placing the mouthpiece of the phone over the computer speaker, phone phreakers could manipulate the telephone system without having to build actual boxes.

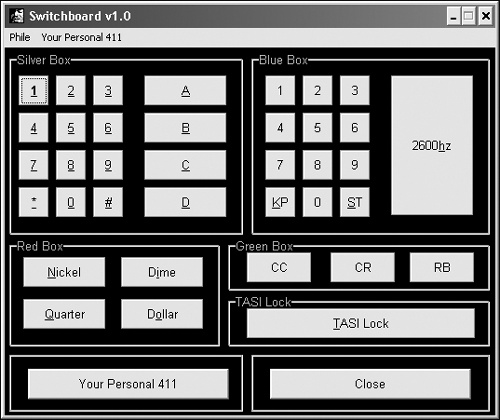

Although telephone color boxes are largely obsolete, many phone phreakers have created software implementations of their favorite ones, dubbed tone generators. For example, Hack Canada (www.hackcanada.com) offers a red box program (called RedPalm) that runs on a Palm handheld computer, and some hacker sites still offer a combination red/blue box program dubbed Switchboard (see Figure 2-1).

Remember, tone generators simply play different tones, just like an MP3 player. Why not simply save those tones as MP3 files for playback on any digital audio device? Why not is right. To download an MP3 tone, visit the Phreaks and Geeks site (www.phreaksandgeeks.com).

Phreaking with war dialers and prank programs

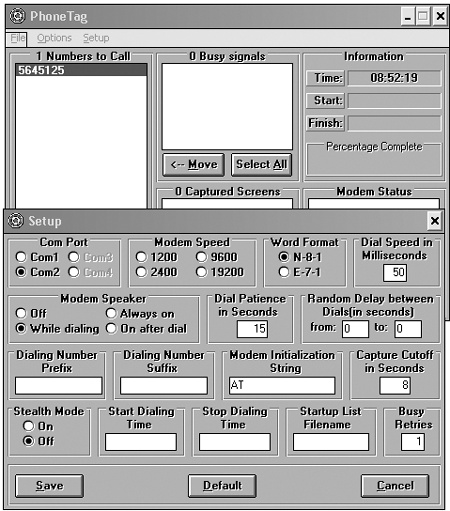

Besides writing programs to mimic telephone color boxes, phone phreakers have also created programs called war dialers or demon dialers. War dialers are an old, but still effective, method for breaking into another computer (see Figure 2-2).

War dialers try a range of phone numbers in a hunt for telephone lines connected to a modem and a computer, which makes every person, corporation, and organization a potential target. The war dialers record the phone numbers that respond with the familiar whine of a computer (or fax) modem, and a hacker can then use this list and dial each number individually to determine what type of computer he has reached and how he might be able to break into it.

For example, many businesses have special phone lines that allow traveling employees to control their desktop computers with their laptop computers and remote-control software, such as pcAnywhere or LapLink. If a hacker finds this special phone number and uses a copy of the same software, guess what? With the right password, he can take over the desktop computer too and then erase or copy all of its files.

Since war dialers repetitively dial a range of phone numbers, such as 483-1000, 483-1001, 483-1002, and so on, many companies try to find and stop any such repetitive dialing. To defeat this, war dialers can be reprogrammed to throw off any possible detection attempts by dialing a range of phone numbers in nonsequential order.

Note

To defeat war dialers, many companies use a callback device that’s only designed to accept specific numbers. When someone wants to connect to the company computer, they need to call from one of the preapproved numbers stored in the callback device’s memory. Once they connect, they send a signal to the callback device to call back to one of the preapproved phone numbers. The caller then hangs up and waits for that call. Since the callback device restricts the phone numbers allowed to connect to the computer, hackers are effectively blocked from breaking into a computer through a modem (hopefully).

Like any tool, war dialers can be used by hackers to break into a computer or by security professionals to probe a company’s vulnerabilities. Since computer security is so lucrative, SandStorm Enterprises (http://sandstorm.net) sells a commercial war dialer called PhoneSweep, which is designed for security professionals to test for any unsecured modems connected to their company’s phone system. Unlike most hacker war dialers, PhoneSweep can generate reports and graphs that show the percentage of phone numbers called that had a modem or returned a busy signal.

As a free alternative to PhoneSweep, download a copy of TeleSweep Secure from SecureLogix (www.securelogix.com). SecureLogix originally sold TeleSweep Secure commercially, but now gives it away for free in the hopes that satisfied customers will upgrade to its Voice Firewall product.

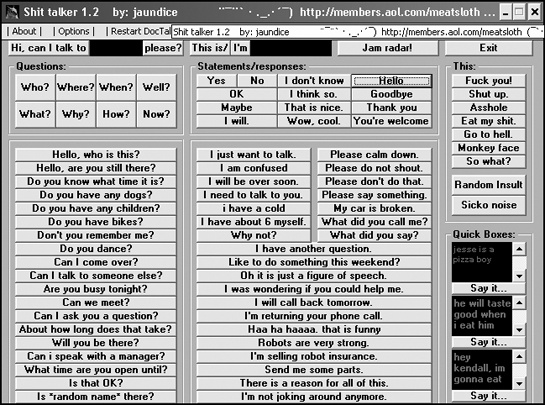

Since war dialers can dial a number repeatedly, they can also be used to harass people. Some of the more unusual harassment programs can dial a single number over and over again at random intervals or play a computer-generated voice to insult a caller the moment he or she picks up the phone (have a look at Shit Talker in Figure 2-3). But if you use one, just remember that caller ID is a common feature nowadays, and allows a victim to track your phone number, so beware.

Phreaking cellular phones

The popularity of cellular phones has attracted both outright thieves and phone phreakers. At the simplest level, stealing cell phone service can be as easy as signing up using a fake or stolen identity, although it’s even easier just to steal someone’s cell phone and use it until the real owner cancels the service.

Of course, both of these methods are fairly crude. For a more sophisticated way to steal cell phone service, thieves have turned to cloning.

Every cell phone contains both a unique electronic serial number (ESN) and a mobile identification number (MIN). Every time someone uses a cell phone, he transmits his unique ESN and MIN to the cell phone network, which verifies that the ESN/MIN combination is valid.

The problem is that when older analog cell phones transmitted their ESN/MIN numbers at the start of every call, anyone with a cell phone scanner could intercept those numbers and store them on another cell phone, essentially cloning the ESN/MIN numbers of a valid cell phone. Any calls made through this “cloned” cell phone would show up on the bill of the legitimate cell phone customer.

Since a cloned phone can only be used until the real cell phone owner notices the outrageous number of additional calls showing up on the bill, some thieves resort to a technique known as tumbling. Originally, tumbling meant using a random ESN and MIN number to make a free call. Once the cell phone company received these random ESN/MIN numbers, they had to validate these numbers. Since this process could take time, the cell phone companies often let random ESN/MIN numbers get one free phone call without validating the numbers. Eventually, the cell phone companies could validate ESN/MIN numbers almost instantaneously, so tumbling took a new form where a thief steals multiple combinations of valid ESN/MIN numbers and uses a different one each time he makes a phone call. Tumbling spreads out the number of illegal phone calls among a large number of legitimate cell phone owners, who are more likely to accept (or not notice) one or two strange calls rather than dozens each month.

In part to protect users from cloning fraud, cell phone companies have introduced digital transmission and encryption, often advertised with cryptic names such as TDMA (Time Division Multiple Access), CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access), GSM (Global System for Multiple Communication), or Spread Spectrum. (Analog cell phones used FDMA, which stands for Frequency Division Multiple Access.)

In additional to encrypting a cellular phone’s ESN/MIN numbers, many cellular phone networks now include voice and radio frequency authentication. Voice authentication can identify unfamiliar calling patterns and radio frequency authentication can identify the unique radio frequency characteristics (known as the fingerprint) of each cell phone.

Such defenses are expensive, which means they’re more often used in big cities while rural areas are left unprotected. To protect yourself, study your cell phone bills every month to identify strange calls. Also, minimize your cell phone use in areas such as airport terminals or parking lots since cell phone thieves scan the airwaves in crowded places where people are most likely to use cell phones.

To keep up with the latest cell phone hacking news and information, visit Cell Phone Hacks (www.cellphonehacks.com), Collusion Magazine (www.collusion.org), or the Temple of the Screaming Electron (www.totse.com), which is shown in Figure 2-4.

While phone phreakers aren’t likely to target your personal cell phone, they are likely to target the cell phones of celebrities like Paris Hilton (if you can legitimately call Paris Hilton a “celebrity”). In 2005, a 17-year-old Massachusetts teenager hacked into Paris Hilton’s cell phone and spread her cell phone number, along with the cell phone numbers and email addresses of Ashlee Simpson, Christina Aguilera, Ashley Olsen, Vin Diesel, former O.J. Simpson attorney Robert Shapiro, Anna Kournikova, Eminem, and Lindsay Lohan, across the Internet.

Not surprisingly, this teenager didn’t hack into Paris Hilton’s cell phone using some undiscovered flaw. Instead, this teenager took advantage of the fact that Paris Hilton’s cell phone was protected by a password. If Paris Hilton forgot her password, she could still access her cell phone by answering the default question, “What is your favorite pet’s name?”

Since Paris Hilton made no secret of her love and affection for her Chihuahua, named Tinkerbell, it was a simple matter of typing in “Tinkerbell” to gain access to Paris Hilton’s cell phone. As this Paris Hilton cell phone hack showed, sometimes the simplest solutions are the best way to sneak past any technical defenses.

Hacking voice mailboxes

Voice mail is the corporate alternative to answering machines. Rather than give each employee a separate answering machine, voice mail provides multiple mailboxes on a single machine. Because a voice mail system is nothing more than a programmable computer, phone phreakers quickly found a way to set up their own private voice mailboxes buried within legitimate voice mailbox systems.

To find a voice mail system, phone phreakers simply use a war dialer to find a corporate voice mail system phone number. (Many even have toll-free numbers for the convenience of corporate executives.) After calling the voice mail system, users often need to press a key, such as * or #, to enter the mailbox. A recording will usually ask for a valid mailbox number, typically three or four digits. Finally, users type a password to access the mailbox, play back messages, or record a new message or greeting.

Most people choose a password that’s easy to remember (and easy to guess). Some people base their password on their mailbox number, either the mailbox number itself or the mailbox number backwards (if the mailbox number is 2108, try 8012 as the password). Others might use a password that consists of a repeated number (such as 3333) or a simple series (6789).

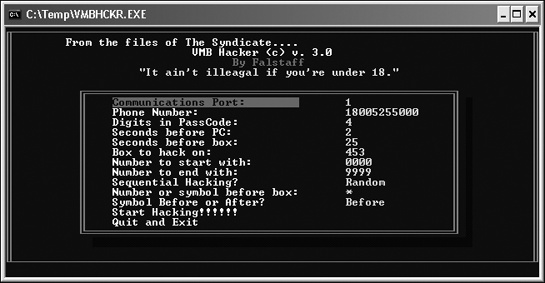

Once a phone phreaker finds a voice mail system phone number, the next step is to guess a password for one or more mailboxes, either by typing in a series of passwords or by running a voice mailbox hacking program, like VMB Hacker, that dials a range of three- or four-digit numbers until it finds a combination that works (see Figure 2-5).

With access to an existing voice mailbox, a phone phreaker can listen to messages and learn more about a particular person or company in order to gather information that may be useful later for prying deeper into a particular company’s computer systems.

In addition, most voice mail systems have several empty mailboxes at any given time, either leftovers from previous employees or extra capacity for anticipated newcomers, and phone phreakers can take over these empty mailboxes and set up a virtual presence for themselves within an unsuspecting corporation. And, if the voice mail system provides a toll-free number, the phone phreaker can receive free phone messages from anywhere.

Note

Even if the voice mail system doesn’t offer a toll-free number, phone phreakers can often reprogram the voice mail system to forward their calls anywhere in the world, essentially getting long-distance phone service at the hacked company’s expense.

The simplest way to defeat voice mailbox hacking is to turn off call forwarding, which will make the system a less inviting target for phone phreakers. Next, make sure that unused mailboxes are really empty, and have no outgoing message.

Despite these precautions, voice mailbox hacking is relatively straightforward, and even changing passwords frequently will do nothing more than delay a hacker by forcing him or her to find a new mailbox to attack and take over. As a result, many companies simply ignore or tolerate this minor transgression. As long as the hackers don’t mess up the voice mail system for legitimate users, it’s often cheaper to simply pretend they don’t exist on the system at all.

Hacking VoIP

Although the early tactics of phone phreakers no longer work on today’s telephone systems, phone phreaking may soon regain popularity as telephone networks switch to VoIP (voice over Internet protocol), which transfers voice calls partially or entirely over the Internet. Whereas early phone phreakers could redirect phone calls through the telephone company’s switches, VoIP phone phreakers will be able to access, intercept, and manipulate the actual voices, which are stored in data packets when they are transferred on phone calls across the Internet.

For example, programs like Vomit (http://vomit.xtdnet.nl), which stands for Voice Over Misconfigured Internet Telephones, or Cain & Abel (www.oxid.it) can snare data packets from a VoIP conversation and convert them to audio files so you can eavesdrop on VoIP phone calls, just like in the early days of the telephone system when teenage boys listened in on supposedly private phone calls. Of course, VoIP phone phreakers will likely follow the same path as their predecessors and end up not only listening to other people’s phone calls, but disrupting them as well.

By accessing individual voice data packets, VoIP phone phreakers can inject their own data packets into a VoIP phone call, including profanity or other words that will change the nature of the call. For example, the speaker might say something as simple as “How are Madge and the kids?” but the person on the other end would hear the original sentence plus any profanity or other comments that the VoIP phone phreaker added. You can imagine the possibilities.

Inserting individual VoIP voice data packets into a conversation may be annoying, but more serious is that phone phreakers could block a valid phone call and replace it with a completely different one. The speaker thinks he’s saying one thing but the listener hears something else. Since every VoIP call gets routed across the Internet through multiple computers, it’s possible for hackers to break into a computer, intercept all VoIP phone calls, and modify the voice messages as they pass by.

By capturing voice data packets and editing them within an audio editing program, phone phreakers can fabricate entire messages and leave them on an unsuspecting victim’s voice mail. The victim will hear what seems to be the voice of a trusted person, but the message may be something that the caller never said.

Caller ID spoofing, whereby VoIP phreakers can mask their true phone number and impersonate another phone number, is even simpler. Spoofing caller ID can trick people into answering telemarketer phone calls, or can make the phone line of identity thieves appear to come from a credible business or organization like eBay or the Red Cross.

By following the trail of data packets, VoIP phone phreakers could even trace a phone call from one person to another, which could come in handy for finding someone else’s phone number. For example, if you were to tap into the VoIP phone of a known drug dealer, you could trace his calls to find the phone numbers of his suppliers (or contacts with corrupt police officers), or tap into a movie star agent’s VoIP network to find the phone numbers of his clients (then eavesdrop on his phone calls and sell any juicy gossip to the entertainment tabloids, much like the reporter who recorded cell phone conversations between Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman).

Just as email has allowed people to send spam for free, so will VoIP allow phone phreakers to hijack a VoIP network and flood it with spam over Internet telephony (SPIT). So not only will people receive spam in their email accounts, but with VoIP, they’ll also risk getting telemarketing calls to their voice mailboxes too.

Or, if phone phreakers simply want to annoy people, they can flood a network with bogus data, creating a clipping attack, which can disrupt or “clip” your phone calls so people can only hear every second or third word spoken. A more malicious phone phreaker might opt for V-bombing, which floods a voice mailbox to prevent someone from receiving valid messages.

In the old days, shutting down the entire telephone network of a major corporation, like Monsanto or Halliburton, used to require understanding of how the phone network worked. But with more corporations relying on VoIP phone networks, shutting down a phone system requires little more than a simple denial of service (DoS) attack that floods the network with more data than it can handle, effectively blocking all phone service along with other Internet transmissions. For a more subtle approach, phone phreakers could selectively block the ports used to make VoIP phone calls so that, while the rest of the phone system appears to work properly, certain people wouldn’t be able to make calls or receive them.

Of course, phone phreakers aren’t the only threat. Vonage, an early VoIP provider, has had its service disrupted by two broadband providers, Madison River and Clearwire, that saw its service as a potential competitor. Madison River blocked all Vonage VoIP calls until the Federal Communications Commission fined it $15,000. Clearwire also blocked Vonage VoIP calls, but Vonage simply developed technical workarounds to avoid the digital blockade.

This Vonage vs. Madison River/Clearwire battle isn’t likely the only fight occurring between VoIP providers and Internet service providers. If phone phreakers want to get paid to hack the phone system, they might find the greatest demand for their services coming from broadband providers who want to “discourage” customers from switching to VoIP services in lieu of the broadband provider’s own telephone services. VoIP has come under attack from governments that want to protect their monopolies over state-run telephone service, too. For example, Costa Rica’s Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad (ICE) tried to regulate VoIP as part of its national telephone service, and other nations are likely to do the same.

Even the FBI sees VoIP as a threat. The agency claims, ironically, that it will be much harder to wiretap VoIP calls than traditional phone calls, and so VoIP could become a “haven for criminals, terrorists, and spies.” (While computer security experts warn that VoIP is more prone to eavesdropping, the FBI claims just the opposite. Go figure.)

Note

For more on VoIP security, visit Voice over IP Security Alliance at www.voipsa.org.

As VoIP phone networks become more popular, their simplicity reduces our dependence on traditional landlines and cellular phone networks as well. After all, why pay for minutes on a cell phone calling plan when you can make that same phone call over a VoIP phone for a fixed monthly rate? Perhaps all the phone phreaking tricks previously done on cell phones will trickle down to mobile VoIP phones too.

Like cell phones, you can’t trust VoIP to keep your conversation private or even connect you to the phone number you dialed. But at least your long-distance phone charges should decrease, which makes avoiding long-distance phone calling charges one of the few phone phreaking techniques that VoIP probably won’t revitalize.

Perhaps the biggest threat to VoIP isn’t protecting your privacy but in providing you with service in the first place. Unlike landline phone service that runs on a separate power grid, VoIP phone service depends on the Internet and computers to remain running. If a power outage occurs, through natural disasters or deliberate sabotage, guess what? A landline phone system may still work, but a VoIP phone system will be dead. With VoIP, the simplest denial of service attack you can do is simply finding a way to pull the plug.