2 Vetting the Source

Integrity is telling myself the truth. And honesty is telling the truth to other people.

—Spencer Johnson,

author of Who Moved My Cheese?

News often provokes the question “Who’s telling the truth?” During development of this book, three people surfaced in the news daily and all of them had millions of people asking, “Can we believe him?” It was an important question because each newsmaker’s actions affected people in many places around the world.

Some people asked a deeper question related to their statements: “Does he believe himself?” That is, does the person himself think he is telling the truth?

The three people are Edward Snowden, Barack Obama, and Vladimir Putin, and it’s their widespread influence through word and deed that was the basis for my decision to discuss them here. We are all in a position to vet the source when it comes to such prominent individuals. We can accomplish it through a combination of critical thinking and techniques the intelligence pros use to read people.

The central fact is undisputed when it comes to Edward Snowden: He leaked classified documents describing surveillance activities of the National Security Agency to media. Those documents covered both domestic and international activities, and therefore affected perceptions around the world of how the United States collects intelligence. (In this context, I define intelligence as something of political, geopolitical, or military value.)

In contrast to the undisputed fact of what Snowden did, the truth of what he did, as well as what followed, is disputed. Key issues include whether or not he ever tried to alert anyone in Congress or the government about his concerns, whether or not he took steps to ensure that no one would be harmed by the leaks, and the reason he ended up in Russia. Controversy over such issues has given rise to conflicting headlines:

“Edward Snowden: Whistleblower or Traitor?” (Al Jazeera, June 8, 2014)

“Edward Snowden’s NSA Leaks ‘An Important Service,’ Says Al Gore” (The Guardian, June 10, 2014)

“More Americans Oppose Edward Snowden’s Actions Than Support Them” (NBC News, June 1, 2014)

“House Members to Edward Snowden: No Mercy” (Politico, May 22, 2014)

“Snowden Leaks Have Hurt American Companies, Tech Executive Says” (Time, June 9, 2014)

A little foreshadowing of a discussion in Chapter 8 on the value of yes-or-no questions with a source who has something to hide gives insights as to why it is so easy for the media and the public to adopt radically opposing views of the truth in this case. In the interview conducted by Brian Williams for NBC News,1 Snowden handled some critical yes-or-no questions as follows:

Williams: “To your knowledge, there is nothing you have turned over to the journalists that is materially damaging or threatening to the national security?”

Snowden: “There is nothing that would be published that would harm the public interest.”

Williams said in his commentary immediately following that portion of that interview, “Note that Snowden didn’t deny turning over military secrets.” In saying that, Williams highlighted the fact that Snowden didn’t answer the question with a simple no. Therefore it’s possible that he gave the media documents that could hurt national security.

Later, Williams asked him, “In your mind, are you blameless? Have you done, as you look at this, just a good thing? Have you performed, as you see it, a public service?”

Snowden: “I think it can be both.”

This is a curious answer to another yes-or-no question, as it’s not clear what “both” refers to. Further, Snowden follows it with what appears to be a planned response about the difference between what is right and what is legal—a setup for a discussion of the value to democracy of civil disobedience. In my past life as a marketing communications executive who sometimes coached my bosses prior to media interviews, I would teach this as a tactic to stay on point. That is, the interviewee walks into the interview knowing that certain points must be made in order to get the complete message across in the interview. Therefore, any question that even brushes up against the topic is an opening to deliver that part of the message.

In the case of Edward Snowden, the listener’s/viewer’s point of view makes all the difference in terms of what is labeled “the truth.” To one person, even violation of the U.S. Espionage Act is moral if the public good is somehow served. To another, violating that law and negative effects related to that criminal act mitigate any public good that may have come from the leaks. To the former, the truth is that Snowden is a patriot; to the latter, it is that Edward Snowden is a traitor to the United States.

But the deeper question of “Does he himself think he’s telling the truth?” is something that can be answered more definitively. It is also at the heart of an exercise in learning how to vet a source. Later in this chapter is a discussion of both verbal and non-verbal indicators of deception; I return to the Snowden interview by Brian Williams during that discussion.

Turning to President Barack Obama, we first should admit that probably every U.S. president in modern times (meaning we have video and transcripts that enable meticulous fact-checking) has been guilty of misleading or even blatantly false statements. The question is this: Is he speaking what he believes to be the truth, or is he deliberately using language that will disguise the truth in the interests of political gain (or political survival)?

This is one time when advocacy journalists can help us vet the source. These are journalists who openly espouse a point of view and deliver news analysis with that bias made clear. But advocacy journalism can play a role in both undermining the truth and illuminating it. Sometimes, a strident point of view twists facts and integrates warped statistics. Other times, advocacy journalists actually catch a piece of the picture (for example, impact of a new law or regulation on certain populations) that so-called objective journalists completely miss or choose to ignore. For a thoughtful listener or viewer, they provoke questions that enable a person to vet the source.

A good example of confusion about the truth of a U.S. president’s statement surfaces in Obama’s keynote at the Democratic National Convention on September 6, 2012. Critics of President Obama, as well as those who wanted to believe both the spirit and substance of what he said, locked on to to assertions such as “We’ve doubled our use of renewable energy, and thousands of Americans have jobs today building wind turbines and long-lasting batteries.”

Was the statement factually correct? Did Obama believe it?

The Washington Post labeled this statement “true with a (good) but” in its September 7, 2012 article on the speech:

As [TIME magazine’s senior national correspondent] Michael Grunwald pointed out on Twitter, this way undersells what happened to green energy under Obama. Wind energy doubled, but solar grew over 600 percent. 85,000 Americans work in wind energy, and in 2010, 5,918 people worked on battery production for electric cars and other renewable energy projects.2

In contrast, Politifact.com (produced by the Tampa Bay Times) labeled the statement “mostly false.” Their definition of “mostly false” is that “The statement contains an element of truth but ignores critical facts that would give a different impression.”3

Relative to the Obama statement, the facts he did take into consideration are:

![]() Net electricity generation from wind, which more than doubled between 2008 and 2011.

Net electricity generation from wind, which more than doubled between 2008 and 2011.

![]() Net electricity generation from solar has more than doubled over the same period.

Net electricity generation from solar has more than doubled over the same period.

![]() During the first five months of 2012, the United States has produced more electricity from wind than it did in all of 2008.

During the first five months of 2012, the United States has produced more electricity from wind than it did in all of 2008.

These are all verifiable statistics from the Energy Information Administration (EIA), a federal agency that collects energy data.

Politifact.com’s determination was that the statement was mostly false. It doesn’t say that Obama’s presentation of trend information for wind and solar are wrong, but that he used the wrong words to describe the trend for renewable energy as a whole—thus helping to render it inaccurate.

Renewable energy also includes hydroelectric, geothermal, and certain biomass energy. According to Politifact.com:

If you put them all together by BTUs, wind energy in 2011 accounted for 11 percent of all renewable-energy production. That’s not 11 percent of all energy production, including coal, oil and natural gas—that’s 11 percent of just the production from renewable sources. Solar, meanwhile, was even smaller. It accounted for about 1 percent of all renewable energy production.

If you look at all types of electricity generation from renewables, the increase isn’t double between 2008 and 2011—it’s 55 percent.4

The journalists and researchers at the Tampa Bay Times that contribute to Politifact.com went on to point out that “Energy and electricity are not the same thing. Not all renewable energy is used to create electricity.” With that as an additional consideration, the impact of renewables slumps lower: “The increase in megawatt hours was about 25 percent, according to EIA data and estimates.”5 But it wasn’t Obama who mentioned electricity; it was the spokeswoman from EIA who defended his statement and couched the progress in terms of electricity.

In short, your determination of whether or not Obama thought he told the truth would have to rest on whether or not:

![]() he had reliable advisors about the subject,

he had reliable advisors about the subject,

![]() he asked good questions about the subject in preparing his speech, and

he asked good questions about the subject in preparing his speech, and

![]() he comprehended both the science and economics of renewable energy.

he comprehended both the science and economics of renewable energy.

In addition, the possibility exists that he deemed the statement “true enough” to use and decided to do so because it would resonate with his audience and the voter base.

The value of this example is suggesting how many variables there are in ascertaining whether a particular person is telling the truth at particular moment in time. And as with the Snowden example, using tools like body language analysis can reveal whether or not the person believes his own words.

Finally, a quick look at Russian President Vladimir Putin gives us more blatant examples of someone who mixes salient omissions and carefully selected facts to project something he wants his audiences to embrace as the truth. Prior to the Sochi Olympics in 2014, Putin’s statement about equal rights in Russia sent fact-checkers in many nations scurrying to reliable sources of information about the rights of homosexuals around the world. The controversial Putin statement, made during an interview with ABC’s This Week (January 19, 2014) and other media outlets, was that in Russia all people are equal, regardless of religion, sex, ethnicity, or sexual orientation, whereas 70 countries in the world have criminal liability for homosexuality.

In a technical sense, Putin was largely correct because homosexuality is not criminalized in Russia, whereas more than 70 countries do have laws on the books banning homosexuality. But his assertion didn’t capture the reality of life for homosexuals in Russia, where employers can fire people for being gay, same-sex couples cannot adopt, and lesbians cannot use artificial insemination to bear children.

Putin himself signed a law in June 2013—ostensibly “protecting” minors—that banned “homosexual propaganda.” It’s broad enough to make events like Gay Pride parades impossible to carry out, presumably because children might be along the parade route. With facts like that in mind, one would have to conclude that Putin deliberately crafted his statement to deceive listeners and readers.

Retired Major General Oleg Kalugin, formerly a top official with the KGB, reinforces that inference by noting: “Nothing is done is Russia today without Putin’s consent. He is in charge of everything.”6

The guidance in this chapter applies to both written and spoken information. The first step is embracing the assumption that what you are about to read or hear cannot be taken as gospel—even if the source is an admired head of state. Keep in mind that even holy leaders such as the Pope and Dalai Lama can make mistakes, too.

Types of Information

There are different types of information, which we might group into the categories of descriptive, anecdotal, statistical, and opinionated: (Examples for the first two kinds of information come with the help of Snopes.com, the excellent Website founded in 1995 by Barbara and David Mikkelson to debunk urban legends and rumors.)

» Descriptive: The information depicts and person, place, thing, or event; it might, for example, tell you how to do something. The following pieces of descriptive information are from Snopes.com’s medical section:

![]() Doctors generally recommend one attempt to cough rhythmically during a heart attack to increase the chance of surviving it. (False)

Doctors generally recommend one attempt to cough rhythmically during a heart attack to increase the chance of surviving it. (False)

![]() Handles of shopping carts are laden with germs. (True)

Handles of shopping carts are laden with germs. (True)

» Anecdotal: These statements convey a short story about an event or individual. In these examples, the anecdotal information relates to rumors of war in the days after the attacks on September 11, 2001:

![]() Three people died of suffocation after sealing their home with plastic sheeting and duct tape. (True)

Three people died of suffocation after sealing their home with plastic sheeting and duct tape. (True)

![]() A shipment of UPS uniforms is missing and presumed to have been stolen by terrorists. (False)

A shipment of UPS uniforms is missing and presumed to have been stolen by terrorists. (False)

» Statistical: Statements featuring numerical data fall into this category. Advertisers and politicians are two types of people who often play fast and loose with the numbers:

![]() In a January 26, 2014 interview on CNN’s State of the Union, Senator Rand Paul criticized Obama’s job-creation efforts through such programs as loan guarantees and said, “What he [President Obama] misunderstands is that nine out of 10 businesses fail, so nine out of 10 times, he’s going to give it to the wrong people.”

In a January 26, 2014 interview on CNN’s State of the Union, Senator Rand Paul criticized Obama’s job-creation efforts through such programs as loan guarantees and said, “What he [President Obama] misunderstands is that nine out of 10 businesses fail, so nine out of 10 times, he’s going to give it to the wrong people.”

![]() According to Smallbusinessplanned.com, which considered three different studies in determining small business survival rates, the reality is that the failure rate is 50 percent after four years. The rate decreases after that, but the “nine out of 10 times” statistic is bogus.

According to Smallbusinessplanned.com, which considered three different studies in determining small business survival rates, the reality is that the failure rate is 50 percent after four years. The rate decreases after that, but the “nine out of 10 times” statistic is bogus.

» Opinionated: Even information capturing an opinion can sometimes get a “false” label because the person who is saying it doesn’t really hold the opinion:

![]() “I think that color looks great on you” is an example of opinionated information that might have no relationship to the truth for the person saying it.

“I think that color looks great on you” is an example of opinionated information that might have no relationship to the truth for the person saying it.

![]() An opinionated statement with more global significance would be “I believe we have the ability to win this war.”

An opinionated statement with more global significance would be “I believe we have the ability to win this war.”

Now, let’s take a look at the categories with the idea in mind that you want to vet the source of the information. Key areas of scrutiny are motivation and presentation.

Motivation

Both types of information can be affected by the motivation of the source. In vetting the source, it is vital to determine why the person wants to give you the information. Is the person selling something? Trying to educate? Hoping to impress you? Wanting to minimize the information exchange? The rapport-building techniques covered in Chapter 3 help illuminate how you can ascertain the motivation of a source.

In his book Good Hunting, Jack Devine describes the way the CIA has traditionally recruited and handled agents to get a clear understanding of their motivation. (An agent in the context of espionage is someone who provides information or other services covertly to the CIA.) Devine is former deputy director of operations, responsible for all of the CIA’s spying operations. He prefaces his remarks by noting that paying for information is actually one way to help clarify the motivation of the source:

As a general operating principle, we select targets who have known access to information we need. Hence, we start from a very strong position, because the source does not have to invent information to get paid. He or she already has the access. Furthermore, a high percentage of our recruitments begin with ideological identification with the United States. Many of them either don’t identify with the political systems in their countries or have been harmed by them. The money is a reinforcing inducement, not the be-all and end-all in a source’s productivity. Plus, there is a work ethic among most agents. They respond to financial incentives and try to collect good information to continue earning them. The issue of false or corrupted information comes into play when you have a walk-in (someone who appears at an embassy and volunteers his services) or a double agent.7

Presentation

Several types of red flags may go up that should cause you to take a deeper look and remain skeptical. Some of them pertain primarily to descriptive or anecdotal information; others tie in more closely to statistical information. Finally, when it comes to opinionated information, an opinion in and of itself is reason to switch on your internal lie detector; the person’s presentation tells you how much to amp it up.

The following two sections provide guidance on verbal and non-verbal aspects, respectively, of a source’s presentation that are clues something may be amiss.

Verbal Red Flags

Descriptive or Anecdotal Information

When he was with the FBI managing counterintelligence efforts, David Major’s job was to “identify and neutralize individuals spying against America.”8 Major now heads the CI CENTRE, teaching people to identify these red flags in his numerous courses on counterintelligence, including a five-day course on asset validation. The asset validation process helps his clients gauge the intentions and veracity of sources and the authenticity of information received from them; in lay-person’s terms, we’re talking about vetting a source. A couple of the things he tells students to consider are the first two bullet points in the following list; the third and fourth come from James O. Pyle, former U.S. Army interrogation instructor and my coauthor of Find Out Anything From Anyone, Anytime. The ways to interact with the source when you spot these red flags are described in chapters that follow. But note well: These glitches in communication that signal a problem don’t only pertain to a home-grown terrorist who might strap explosives to his body and jump on a D train to Brooklyn. They apply to anyone if your life.

» Look for anomalies in the information. Any gaps or irregularities suggest you need to ask your source more questions. A common example is one that the parent of any teenager can relate to. You say, “We agreed you’d be home by 10. What were you doing that you couldn’t get home until 11:30?” Your teenager then gives you a rundown of his evening that doesn’t exactly explain the missing 90 minutes.

» Be skeptical if you don’t get a straight answer to a straight question. One of the simplest and most effective tools that any interrogator has is direct questioning. You probably aren’t an interrogator per se, but when you need to know something about a person, place, thing, or event in time, you often ask a direct question about it. For example, you might ask your spouse why he’s worked late four out five nights this week. When his answer dances around that direct question, you have every reason to be suspicious.

» Be wary if your source majors in the minor information or minors in the major information—that is, if the person seems to be misplacing emphasis that should evoke suspicion about the veracity of the statement. Another way of describing “majoring in minor information” is being hypercritical about some aspect of a statement to distract from a more important discussion. When one of my author friends was accused of a copyright violation because of using a graphic that another author laid claim to, my friend said simply, “I sought permission, you gave it, and I included proper attribution in the book.” The aggrieved party, who thought he would make some money if he could prove a violation, came back with an e-mail that accused her not including his Web address in four different locations in the book where he thought it should go. That is, he used nitpicking as a negotiating tactic, putting emphasis on a minor point to distract from the fact that he had no major point.

» The converse of this is minimizing a significant point. In the copyright example, if my friend had responded to the complainant by casually dismissing the graphic as unimportant to the book’s content, noting that readers would pay more attention to a positive story she told about him, she would be minoring in the major information.

» Watch/listen for verb tense changes and pronoun number changes. They are mechanisms people may use, whether consciously or subconsciously, to distance themselves from an event, person, or idea. For example, if a person has been saying, “I did this” and “I went there,” and then suddenly switches to “and then we decided to do that,” you should wonder who “we” are and why the source felt a need to involve others. There may, in fact, be no “we.” It’s possible that the change to a plural pronoun is a psychological slip on the part of the source who feels uncomfortable admitting that a particular action was his alone. People often do this to spread the blame for bad decision.

In 1999, rumors started circulating widely that Lance Armstrong was using performance-enhancing drugs. In August 1999, he made his first public statement about the accusation. Oddly enough, at some point, he began talking about himself in the third person: “From the beginning, people didn’t want Lance Armstrong for a number of reasons. Either he was not going to be able to race again at a high level or he was a risk of bad publicity.”9

Similarly, if a person who has been telling you a story in the past tense shifts to a present tense, for example—as though she’s putting you into the scene—you have reason to question the presentation. Let’s say Sarah’s boss has suggested that she’s at fault for losing an important client. He asks her what happened at a critical meeting with him. She says: “Zach and I told the client we could have the deliverables by Thursday. We made an appointment to present them at a meeting. So Thursday rolls around and here we are getting ready to walk into the meeting and Zach says to me, ‘I wonder how tuned in they are to the importance of social media.’”

Statistical information

As soon as you see or hear statistical information, automatically question it. Jack Devine told me, not jokingly, that when people at the CIA would give him a report with numbers in it, “I would send it back without reading it.”10 His standard request was that whoever submitted the report should go back and check the numbers and flesh out any explanation that would clarify their reliability and value.

Award-winning journalist Glenn Kessler, who contributes to the Fact Checker column for the Washington Post, offered these tips on statistics information; these specifically pertain to the failure rate of “9 out of 10 businesses” cited by Rand Paul:

1. What’s the time frame? Two years, five years, 10 years? That can make a big difference.

2. Does “fail” mean that it goes out of business because it was not financially viable? Or does that also include data about successful enterprises that merge with another company?

3. Wouldn’t failure rates be different for some industries than others? Does it make sense to lump all businesses together?11

To make them more generic, consider Kessler’s three points in these terms:

![]() Time period covered by the statistics.

Time period covered by the statistics.

![]() Definitions of keywords and concepts.

Definitions of keywords and concepts.

![]() Similarities and differences between elements of the group covered by the statistics. For example, statistics on “immigrants of color” in the United States would need a clear explanation, because immigrants from the Philippines and Kenya might have very different situations and lumping them together could yield screwed statistical data.

Similarities and differences between elements of the group covered by the statistics. For example, statistics on “immigrants of color” in the United States would need a clear explanation, because immigrants from the Philippines and Kenya might have very different situations and lumping them together could yield screwed statistical data.

Opinionated Information

At least two types of verbal cues come into play with opinions: the use of modifiers to amplify the point of view, and the use of words that distance the source from the opinion.

Suspect statement with modifiers: “I really believe very strongly that she never would have said that to you if she hadn’t been drinking too much.”

Less suspect: “I believe she never would have said that to you if she hadn’t been drinking.”

Suspect statement with distance: “I’ve always tended to be of the opinion that global warming poses threats to the economy as well as to our health.”

Less suspect: “I think global warming poses threats to the economy as well as to our health.”

On January 11, 2008, Deepak Chopra posted an essay on the Huffington Post site by author and biologist Rupert Sheldrake, who is most known for his work in parapsychology. In the essay he sent to Chopra, Sheldrake explains how we was suckered into a negative media experience with fellow scientist and well-known atheist Richard Dawkins. It is possible Sheldrake could have prevented the fiasco if he’d had his radar up about the use of modifiers as a warning of deception.

Sheldrake notes that the reluctance he had at first to participate in Dawkins’s documentary series was due to a previous television program called The Root of all Evil, which was edited to minimize the thinking of everyone except Dawkins. Sheldrake was told the following via e-mail: “…the production team’s representative assured me that they were actually interested in facts, and that ‘this documentary, at Channel 4’s insistence, will be an entirely more balanced affair than The Root of All Evil was.’ She added, ‘We are very keen for it to be a discussion between two scientists, about scientific modes of enquiry.’”12

The overcompensating phrases “entirely more balanced” and “very keen” probably stood out to you, and they should. The production assistant’s failure to communicate in a straightforward manner about what the program would be—not what it would be in comparison to another show or what the team was “keen” on it being—are signs of an attempt to cloak the truth.

When Sheldrake later challenged the program’s director, Russell Barnes, and told him about the assurance the show would be a balanced scientific discussion, Barnes asked for proof. Sheldrake provided the e-mails. He recalls: “He [Barnes] read them with obvious dismay, and said the assurances she had given me were wrong.”13

David Major provides an additional insight into the kind of statements and behavior—and into the mind itself—of someone who is trying to deceive:

We taught people in interrogations of criminals to accuse them (allow them to rationalize their criminal activity) of doing the crime. How they respond is very telling about guilt or innocence. The person who is innocent wants to get up and walk out. He’s denied the charge and there is nothing more to say. He just gets mad at you. The person who is guilty will hang around; he wants to see what you’ve got. It’s like playing poker. He will stay longer and talk to you. The longer he will stay and talk, the greater the chance he’s guilty.14

Non-Verbal Red Flags

Lena Sisco offers a course on body-language basics called “How to Be a Body Language Expert: Be a REBLE.” Sisco, who is president of The Congruency Group, trains U.S. Department of Defense personnel in interrogation, tactical questioning/debriefing, site exploitation, elicitation, counter-elicitation, cross-cultural communications, human intelligence (HUMINT) policy, detecting deception, and behavioral congruency.

Her term REBLE stands for a five-step program on how to accurately read body language and detect deception: Relax, Establish rapport, Baseline, Look for deviations, and Extract the truth. Chapter 3 is devoted entirely to establishing rapport, and you will do the best job if you are relaxed when you meet the source. For that reason, “R” and “E” will be covered together. Chapters 4 and 5 describe the processes you can use to extract the truth. To complete the discussion of vetting the source, therefore, the focus is on determining baseline and spotting deviations from baseline.

To get a reliable baseline for someone, study that person in an unstressed state. Know how he normally acts as well as sounds. Regarding the latter, if an individual is well-spoken, part of his baseline might be clear and correct pronunciations of words. A deviation from baseline would be suddenly dropping the “-ing” at the end of word and turning into “-in’.” I’ve heard everyone from acquaintances to the president of the United States do this in situations where they are a bit uncomfortable. Yes, this is a verbal red flag, but when you hear it, it’s your cue to look for non-verbal signs that reinforce your guess that your source has deviated from baseline.

Some people have quirky movements such as a jumpy foot or an eye twitch even when they’re relaxed. These can be part of a person’s baseline. So even though you don’t see such movements as normal in the context of your own body language, they may be the norm for your source.

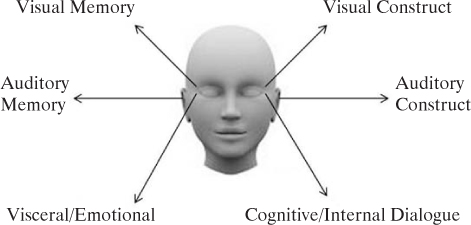

There is no absolute rule of where you start in your evaluation of baseline and spotting deviations, so that fact that I’m going from eyes to toes is arbitrary. The organizing principle I’m using is that the eyes are closest to the brain the toes are farthest away.

Eyes

Grasping the meaning of eye movement is considered by many of us to be a foundation skill in lie detection. However, there are at least a couple of schools of thought on how to go about reading eye movement. It should also be noted that psychologists are not in agreement that there is a correlation between eye movement and thought; some actually think it’s useless in lie detection. My experience with reading eye movement comes from real-world observation, so I’ve never conducted tests shaped by rigorous scientific protocols like some of those who debunk the relationship between thought and eye movement. I will say this, though: I’ve been watching people and doing demonstrations with audience members and body language students for 10 years, and I’ve seen a great deal of evidence that a correlation exists.

The most popular system of reading eye movement comes out of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP), an approach to performance improvement and communication created by Richard Bandler and John Grinder in the 1970s. The name itself contains the elements that Bandler and Grinder see as connected: “Neuro” relates to nerves or the nervous system; “linguistic” refers to language; “programming” suggests patterns ingrained through experience.

According to NLP, automatic eye movements often correspond to particular thought processes and indicate that a person is accessing different areas of the brain. Bandler and Grinder did not originate the idea; they simply took it to a new level. The idea that eye movements might somehow be related to different parts of the brain being engaged goes back to William James, who talked about it in his 1890 book, Principles of Psychology:

In attending to either an idea or a sensation belonging to a particular sense-sphere, the movement is the adjustment of the sense-organ, felt as it occurs. I cannot think in visual terms, for example, without feeling a fluctuating play of pressures, convergences, divergences, and accommodations in my eyeballs.… When I try to remember or reflect, the movements in question…feel like a sort of withdrawal from the outer world. As far as I can detect, these feelings are due to an actual rolling outwards and upwards of the eyeballs.15

In NLP terms, James is describing a “visual eye-accessing cue”—that is, eyes moving up and to the left or right for visualization. Studies done just before and shortly after Bandler and Grinder debuted NLP pointed to essentially the same conclusions that they drew about visual and auditory accessing cues as well as indicators of deep thought or calculation and deep feelings about someone or something.

Although the left/right relationship might differ from person to person, the point is that looking to one side signals memory, and other side, imagination, when we’re talking about visual or auditory cues. Eyes down means either emotion or thought.

In this image, the memory and thought cues are to the subject’s right:

Following are a few questions you might ask if you want to do casual experiments with people to see how their eyes move in response. Keep in mind that we are about to build on this information with other thoughts on eye movement, so this is not an absolute test:

![]() What does your kitchen look like? (visual memory)

What does your kitchen look like? (visual memory)

![]() If you could transport yourself to the surface of Venus, what would it look like? (visual construct)

If you could transport yourself to the surface of Venus, what would it look like? (visual construct)

![]() What are the opening notes of your favorite song? (auditory memory)

What are the opening notes of your favorite song? (auditory memory)

![]() What do you think a baby giraffe sounds like when she wants her mother? (auditory construct)

What do you think a baby giraffe sounds like when she wants her mother? (auditory construct)

![]() How did you feel when you lost someone very close to you—mother, father, friend? (visceral/emotional)

How did you feel when you lost someone very close to you—mother, father, friend? (visceral/emotional)

![]() When you bought your last car, what percentage of your income went to payments? (cognitive/internal dialogue)

When you bought your last car, what percentage of your income went to payments? (cognitive/internal dialogue)

Although I said earlier that I have seen the NLP system work countless times, I also had it fail me once. In order to help people in the room make sense of what occurred I had to take the focus away from the NLP system and put it on the meaning of what had happened.

In brief, in a Senior Executive Service (SES) class I was teaching for the Department of Homeland Security, students paired up for the eye movement portion of the session. One student asked questions like the previous one, and the other member of the pair responded. The way I do the exercise, no one is briefed in advance on what they might discover; the observer is told simply to observe. With the exception of one pair, I got what I expected, which was affirmation that the way eyes wandered seemed to correlate with thought. Some people were up left for memory, some were up right, and so on. What happened with that lone pair caught me a bit off guard. The observer in the pair described what seemed to her to be random eye movements—nothing that corresponded to what she was now seeing on the NLP chart on the slide I displayed.

It’s a prime example of Lena Sisco’s caution: “I use NLP, but it’s only part of the game. NLP alone is not necessarily accurate. People’s eyes move in different directions—lots of different ways.”16

The question with the SES class was this: Was there a system for reading eye movements like her partner’s? The answer: yes, but it sure isn’t NLP. The way to read him was to do a thorough baseline before jumping to any conclusions about whether he might be accessing imagination or memory. Watch what his hands do, what his feet do, his facial expressions while he’s talking. Listen to his rate of speech, choice of words, and every other aspect of his communication that constitutes what’s normal for him. Deviations from that baseline would then be the first signal that perhaps he was constructing information rather than recalling it.

The anomaly was actually a perfect opportunity to reinforce the point that no single system of reading people is 100-percent reliable in giving us a definitive answer on someone’s truthfulness. It also proved to be a great setup for the lessons on reading the rest of the body to determine baseline and spot deviations from it.

Face

The ability to manipulate the muscles in the face to convey an emotion should be thought of as being on a continuum. Some emotions are very easy project at will—they are easy to fake—whereas a few others involve facial muscles in such a way that few people have the control needed to fake them. So in an effort to spot deviations from baseline, for now, let’s consider facial expressions that are probably unintended.

With the baseline issue in mind, you will not be focused on the universality of certain expressions—that is, the expressions of emotion Paul Ekman identified as common to all humans: disgust, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and happiness. Instead, the spotlight is on emotions that activate reliable facial muscles. This is also an Ekman concept and he claimed that activity of them communicates the presence of specific emotions.17 As a corollary, the theory is that spontaneous activation of reliable facial muscles is really hard, if not impossible, to suppress.

A team of researchers from the University of Geneva tested Ekman’s theory. They concluded that the reliable muscles “may indeed convey trustworthy information about emotional processes.”18 But there was a caveat: The researchers also concluded that these muscle activations were shared by several emotions rather than characteristic of just one.

For your purposes in spotting a deviation from baseline, the important thing is this: You’re seeing something you hadn’t seen before and your source couldn’t help himself. Something you said triggered an involuntary response.

According to the researchers, the spontaneous response is likely to convey one of the following emotions. Several reliable muscles may be involved; a non-technical description of some muscles the person can’t control, and what they’re doing, are listed next to the emotion:

![]() Hot anger—margin of the lip tightened.

Hot anger—margin of the lip tightened.

![]() Panic fear—lip stretched.

Panic fear—lip stretched.

![]() Elation/joy—lip corner pulled.

Elation/joy—lip corner pulled.

![]() Sadness—lip corner depressed.

Sadness—lip corner depressed.

There is further discussion of facial expression in Chapter 8 in terms of what the emotion information tells you about how to extract the truth from source who is trying to hide something.

Arms and Legs

In observing arms, legs, and the body parts they are attached to, it’s useful to talk in terms of concepts defined and popularized by Gregory Hartley, with whom I wrote several books on body language and interpersonal skills: illustrators, regulators, barriers, and adaptors.

![]() Illustrators are movements that punctuate a statement.

Illustrators are movements that punctuate a statement.

![]() Regulators are movements used to regulate another person’s speech.

Regulators are movements used to regulate another person’s speech.

![]() Barriers are postures and objects that put separation between you and another person.

Barriers are postures and objects that put separation between you and another person.

![]() Adaptors are actions that release stress.

Adaptors are actions that release stress.

The way people usually move their arms and legs to illustrate or accent a point can vary greatly depending on cultural norms. Those customs and habits may be shared by a nation, a gang, a club, or a family. It’s not the size of the group that matters as much as its influence on behavior. The variance in what is “normal” is therefore a big reason why you need to observe an individual objectively to determine his baseline. Assuming that he’s emotional about a situation just because his gestures are more outgoing than yours, for example, is flawed thinking.

So with illustrators, watch how the person moves her arms, stands, crosses her legs, and so on while she’s under little or no stress. Deviations from whatever is typical for her—and that could be more or less expressive movements—signal that she’s no longer in a relaxed state.

Regulators tend to be deliberate movements that you use to encourage someone to continue talking, try to speed up the conversation, or perhaps stop it altogether. A person in a relaxed state will probably use regulators such as nodding the head when listening to another person talking. Signals of impatience when someone is talking—taking a step toward a door, for example—indicate tension. In the situation where you are the one talking and asking your source questions, watch the person to note if he’s doing anything that suggests “Hurry up! I want you to stop talking so I can get out of here!”

People often use barriers when they are uncomfortable. Watch people at a reception or other social event where they are meeting for the first time, or perhaps don’t know each other well. You will see men and women clutching a glass with both hands and holding it in front of them. People will hold their plate of cheese and crackers directly in front of them as they are talking with another person. Look around the room and observe people in animated conversation—people who seem to know each other. They may be drinking, but the bottle of beer is in one hand while the other hand is gesturing, or the cheese plate is resting on a table and the person is using both hands to illustrate something he’s saying.

These same differences can be seen in myriad professional situations. Whether the barrier is an object, such as a cell phone or laptop, or a body posture, such as arms crossed in front of the body, the person is exhibiting some level of discomfort. In the course of vetting your source, watch for any change in the way the body or an object is used to come between you and the person.

Adaptors are nervous, self-soothing gestures you do without thinking. They can make other people feel uncomfortable around you, but if you ask them, they might not even be able to tell you exactly why they feel uncomfortable. When you are asking a person questions to determine level of truthfulness, even if you’ve established a good rapport with him, the questions may make the person feel ill at ease. That doesn’t mean what you hear next will be laced with deception, but it does mean that something you said has caused his stress level to rise.

Fingers and Toes

The extremities are far away from the brain when you compare them to facial muscles. They are less in your control, therefore, than your mouth or eyebrows are. If you want to see signs of stress leaking from someone’s body, watch his or her extremities because most adaptors involve fingers and toes. Women tend to use relatively small movements, such as rubbing their fingertips together, touching their hair, playing with an earring, and wiggling their toes. Men may wring their hands, click a pen, or drum their fingers on a table.

In the course of the first book we did together, How to Spot a Liar, Greg Hartley told me that it wasn’t uncommon for someone in one of his interrogation classes to signal intent with his feet and toes. He would sit a student in a chair at the front of the classroom for an exercise, which could be something psychologically challenging involving questioning skills or rapport-building. He said it was rather common for the student’s toes to be pointed toward the door.

Throughout this section, the focus has been on the source’s baseline and deviations from it. But the concept of detecting deviations from baseline can be viewed in two ways: from the point of view of the questioner and the point of view of the person answering questions.

![]() From the questioner’s perspective, deviations suggest that the person’s presentation of the answer reflects stress. Does evaluation of the content either confirm or refute suspicions?

From the questioner’s perspective, deviations suggest that the person’s presentation of the answer reflects stress. Does evaluation of the content either confirm or refute suspicions?

![]() From the source’s perspective, deviations suggest that the questioner has some stress associated with what he is asking. He has emotional attachment to it, and that emotion is leaking out.

From the source’s perspective, deviations suggest that the questioner has some stress associated with what he is asking. He has emotional attachment to it, and that emotion is leaking out.

The scan from eyes to toes from the previous sections provided insights into deviations from baseline. Some of those deviations are subtle. Here is a list of sample deviations that are more obvious and should trigger an immediate awareness that the person is under stress:

![]() Becoming more or less fidgety.

Becoming more or less fidgety.

![]() Stiffening of posture.

Stiffening of posture.

![]() Use of noteworthy adaptors that involve self-preening, such as adjusting a tie or scarf or seeming to brush lint off a jacket, or self-soothing, such as massaging the neck.

Use of noteworthy adaptors that involve self-preening, such as adjusting a tie or scarf or seeming to brush lint off a jacket, or self-soothing, such as massaging the neck.

![]() Shift in pitch, voice, or pace of speech.

Shift in pitch, voice, or pace of speech.

![]() Use of fillers such as “um,” as though the person needs time to think about what to say next.

Use of fillers such as “um,” as though the person needs time to think about what to say next.

These kinds of specific changes in voice and body get a closer examination in Chapter 8.

Red Flags in Real Life

When I first saw Brian Williams’s interview with Edward Snowden, my response as someone who has studied verbal communication for decades and non-verbal communication for more than 10 years was, “He’s deceitful.” I made notes about why I felt so distrustful of Snowden and wondered what the scuttlebutt was in the ever-growing community of communication experts.

I discovered there were lots of people who disagreed with me. I also discovered that the preponderance of credentialed experts felt as I did: The interview proved him to be a liar.

Earlier in this chapter, I cited a couple of instances in which yes or no questions went unanswered. Those were among the verbal signs that Snowden had a script running in his head, with “yes” and “no” not being answers he wanted to give. He wanted to convey particular information, not give a definitive response. It was the same with his response about why he ended up in Russia: It was a slide-slip that evaded the reality that his passport was revoked prior to boarding the plane in Hong Kong for Russia, so questions remain as to why he was allowed to board the flight.

Similarly, his non-verbal communication seemed scripted to me. Dr. Nick Morgan, who has written extensively about the subject of non-verbal communication for Forbes, expresses the same first impression I had about the way Snowden sat. He began with his legs far apart, with feet planted firmly at the edge of the chair: “It came off as either genuinely deliberate or trained.”19 Later on the in the interview, he had one leg thrown over the other, with the right foot at the left knee in a figure-four. It’s a very manly pose in Western society, conveying confidence or even arrogance. During the remainder of the interview, he alternated between the two leg positions.

Other indications include:

![]() Williams’s question about ending up in Russia evoked a snicker and evasive eye movement.

Williams’s question about ending up in Russia evoked a snicker and evasive eye movement.

![]() At a number of points in the interview, notably when Williams asked him about self-perception—noble whistleblower or hideous traitor—Snowden pursed his lips. Janine Driver, president of the Body Language Institute and a partner of Lena Sisco’s in body language instruction, cautions: “When we don’t like what we see or hear, our lips disappear. When we see notorious liars or people holding something back, their lips will disappear.”20

At a number of points in the interview, notably when Williams asked him about self-perception—noble whistleblower or hideous traitor—Snowden pursed his lips. Janine Driver, president of the Body Language Institute and a partner of Lena Sisco’s in body language instruction, cautions: “When we don’t like what we see or hear, our lips disappear. When we see notorious liars or people holding something back, their lips will disappear.”20

In this reality check, I’d agree with Nick Morgan, who concluded that Snowden’s body language suggests a “willed performance.” He adds, “I wouldn’t trust anything the man said.… There is something else going on here.”21

In the upcoming chapters, you find out how intelligence pros forge relationships with the sources they’ve vetting—like them or not, and trust them or not—and then take them down a conversational path to get the sources to level with them.