3 Building Rapport

There are traits—some ethnic, perhaps, and some the result of upbringing—that predispose certain people to be gifted at connecting with others and eliciting information. For the same reasons, other people have no gift for these things and it would be harder for them to cultivate rapport-building skills.1

—Elizabeth Bancroft,

executive director of the

Association of Former

Intelligence Officers

People who know me always call me Peter. When people call me Edwin—my legal first name—I know they are either selling insurance or running for office. You would think people in those professions would have done some homework before they try to connect with me.2

—E. Peter Earnest,

former Senior CIA National

Clandestine Service Officer and

executive director of the

International Spy Museum

Lyndon Johnson, the 36th President of the United States, famously noted that the “most tragic error” of his administration “may have been our inability to establish a rapport and a confidence with the press.”3 As a result, Johnson stated that he did not think the press understood him and, as a corollary, did not publish or broadcast the truth of what the administration undertook and accomplished.

In expressing this concern, Johnson suggested that historical records may therefore suffer from his failure to build rapport. The same can be said for our personal histories. Knowing how to build rapport is the foundation for leaving a legacy of truth.

Maslow’s Folly

Everyone has needs, doubts, and insecurities. That is the first concept you need to embrace in honing your skills of rapport-building. The process of establishing a connection to another person to gain trust—and truth—centers on showing respect as you address his or her needs, doubts, and insecurities.

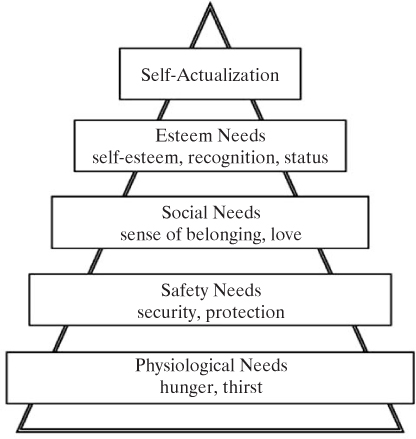

In 1943, psychologist Abraham Maslow published a paper titled “A Theory of Human Motivation,” in which he described a hierarchy of needs, often depicted as shown on page 69.

The premise is that, unless “deficiency needs”—those on the lower part of the pyramid that have to do with survival and security—are met, then an individual will not be motivated to fulfill “growth needs.”

Maslow had some valid things to say but wasn’t completely correct, according to 21st-century behavioral science. And so, the art and skill of rapport-building has morphed, perhaps not so much in what people do with their sources to motivate them to tell the truth, but why they do it. A battlefield interrogator who wanted to build rapport with a prisoner, for example, may have begun the process by making sure he had something to eat and a sense that he would not be physically abused. He might still do that, but rather than view the actions primarily as ways to address deficiency needs, he would do them to demonstrate respect for the other person. The difference is more than a nuance; the latter recognizes that what means most to the individual is being respected and not simply being more physically comfortable.

Researchers in various fields have taken different approaches that explored aspects of the question “What motivates people?” In 2011, University of Illinois researchers Louis Tay and Ed Deiner published results of five-year, multi-cultural study that directly put Maslow’s hierarchy to the test. Their paper, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, was titled “Needs and Subjective Well-Being Around the World.” Two questions at the heart of their study were: “Is the association of specific needs with subjective well-being dependent on the fulfillment of other needs?” and “Are needs typically fulfilled in the order described by Maslow?” One of their main conclusions was this: “A person can gain well-being by meeting psychosocial needs regardless of whether his or her basic needs are fully met.”

Mutual of Omaha has a series of commercials they call “A-ha Moments.” One of them is a touching story of man trying to help a homeless person. He asks, “What do you need?” The man says he just wants him to shake his hand. This is anecdotal evidence that pairs well with academic research asserting that the desire to connect is more powerful than the desire for food or safety.

The Scharff Method

When you have the skills of rapport-building—to make another person feel connected to you—you can even turn a hostile source into someone who interacts with you in a productive way. This is what Hanns Scharff did; he is the German Luftwaffe interrogator whose psychological techniques of connecting positively with prisoners have shaped U.S. non-physical interrogation practices in modern times.

Sharff was a self-taught interrogator who became fluent in English before the war while working in South Africa. Prisoners expected harsh, Gestapo-style treatment when they were marched into the room at Dulag Luft POW Camp, where they would be interrogated by him. Instead, they met a man who would soon draw out of them far more than name, rank, and serial number.

Key features of the Sharff method, which partially depended on the fact that prisoners were held in solitary confinement upon their arrival at the camp, included Sharff’s own preparation, reinforcement of the prisoners’ sense of insecurity, and establishing a respectful and comforting connection that relieved their sense of isolation.

![]() He tried to know everything possible about the prisoner before the interrogation began. He collected information about the pilot’s military service, as well as his personal circumstances. He wove in such things as travel times from one place to another that would be familiar to the prisoner. Sharff’s homework and insertion of relevant details into his conversation with prisoners helped him create the illusion that he knew a great deal about their military activities. It was psychologically disarming to prisoners who assumed he knew more than he did, so they were inclined to disclose information. It also laid a strong foundation for building rapport. Not only did Scharff speak English, but he also seemed to have a familiarity with their lives, values, and situations.

He tried to know everything possible about the prisoner before the interrogation began. He collected information about the pilot’s military service, as well as his personal circumstances. He wove in such things as travel times from one place to another that would be familiar to the prisoner. Sharff’s homework and insertion of relevant details into his conversation with prisoners helped him create the illusion that he knew a great deal about their military activities. It was psychologically disarming to prisoners who assumed he knew more than he did, so they were inclined to disclose information. It also laid a strong foundation for building rapport. Not only did Scharff speak English, but he also seemed to have a familiarity with their lives, values, and situations.

![]() He made it clear to the prisoner that working with him and the Luftwaffe was far preferable to being labeled a spy, with his fate then being in the hands of the Gestapo. The message kept prisoners off balance a bit, reminding them they were vulnerable, and at the same time gave them a reason to draw closer to Sharff.

He made it clear to the prisoner that working with him and the Luftwaffe was far preferable to being labeled a spy, with his fate then being in the hands of the Gestapo. The message kept prisoners off balance a bit, reminding them they were vulnerable, and at the same time gave them a reason to draw closer to Sharff.

![]() He displayed friendship. He went for walks in the woods with the men, took them to the zoo, and gave them flights in a German fighter plane. Depending on the environment and how that engendered certain kinds of conversation, the prisoners leaked myriad types of information, from social habits of military personnel to aircraft capability.

He displayed friendship. He went for walks in the woods with the men, took them to the zoo, and gave them flights in a German fighter plane. Depending on the environment and how that engendered certain kinds of conversation, the prisoners leaked myriad types of information, from social habits of military personnel to aircraft capability.

Sharff claimed that his rapport-building skills enabled him to obtain information from 90 percent of all prisoners.4 Mastering techniques such as those used by Sharff positions you perfectly to get the truth from someone.

Causes of Resistance

At the heart of these positive rapport-building techniques, there is perception of what motivates people to resist a connection to another person, even though that may be the very thing they seek. Here are some reasons why you and your source may have some significant barriers to making a connection:

![]() One or both parties perceive that there is no shared value system or standards of morality. For example, Scharff represented an ideological opposite to his prisoners. His stood for a regime that was morally abhorrent to them. Similarly, people entrenched in different political parties may have zero motivation to connect.

One or both parties perceive that there is no shared value system or standards of morality. For example, Scharff represented an ideological opposite to his prisoners. His stood for a regime that was morally abhorrent to them. Similarly, people entrenched in different political parties may have zero motivation to connect.

![]() The source feels as though the person asking questions doesn’t have a positive relationship with his team or friends; therefore, important relationships aren’t getting the respect they deserve. This is a relatively common situation in a workplace where senior staff members, or bosses, are “them” and everyone else is “us.” When one of “them” asks questions of people working for him, they are not inclined toward the kind of interaction that engenders trust or leads to the truth.

The source feels as though the person asking questions doesn’t have a positive relationship with his team or friends; therefore, important relationships aren’t getting the respect they deserve. This is a relatively common situation in a workplace where senior staff members, or bosses, are “them” and everyone else is “us.” When one of “them” asks questions of people working for him, they are not inclined toward the kind of interaction that engenders trust or leads to the truth.

![]() Negative emotions dominate. When Allied pilots first met Scharff, they had just gone through the shock and humiliation of capture, and then were thrown into solitary confinement. Initially, they were emotionally blocked from connecting with their interrogator no matter how nice he seemed. And think about how hard it could be for someone who had been traumatized by a doctor as a child to trust doctors as an adult. Even in a critical-care situation, he might not feel comfortable telling a doctor the truth.

Negative emotions dominate. When Allied pilots first met Scharff, they had just gone through the shock and humiliation of capture, and then were thrown into solitary confinement. Initially, they were emotionally blocked from connecting with their interrogator no matter how nice he seemed. And think about how hard it could be for someone who had been traumatized by a doctor as a child to trust doctors as an adult. Even in a critical-care situation, he might not feel comfortable telling a doctor the truth.

Before trying to establish rapport with someone from whom you are seeking the truth, consider if there might be such ideological, social, or emotional barriers that will make your task very difficult.

Another barrier to true rapport is a threat. In some circumstances within law enforcement, military interrogation, and similar circumstances involving a suspect, the questioner may try a negative approach to building rapport. In other words, the connection may come out of desperation because the suspect feels threatened. This chapter doesn’t explore those techniques, nor are they advocated anywhere in this book. A bond shaped by intimidation is not the most effective way to get the truth. You might get a few facts, but if a person’s only reason for giving you information is that he’s is a state of fear, he’ll hold something back. Information is the only protection he has that you won’t fire him, beat him up, or throw him in jail, so why would he give you the whole truth?

10 Rapport-Building Techniques

The Congruency Group’s Lena Sisco, also referenced in Chapter 2 (about reading body language to vet sources), teaches “Top Ten Rapport Building Techniques,” which bring a Sharff-like approach into our 21st-century, everyday circumstances. Before going into them, however, note that the “R” in her REBLE approach to reading body language is an important precursor.

Relaxing is necessary preparation for achieving your objective of establishing rapport to get the truth. Sisco offers a caution about the importance of relaxation in conveying a positive first impression: “The minute you feel stupid is the minute your look stupid. Feeling nervous or anxious causes your body to go through particular physiological responses. Rapid heartbeat, hard swallowing, stuttering, slouching—it all happens and people can’t control [these responses]. Before the body gets to that fight-or-flight state, you have to relax yourself.”5

The way to do a state transformation to be more relaxed is through power poses and breathing. To a great extent, your sense of relaxation reflects how confident you feel. What you do with your body affects how you feel about yourself. I’ve done an exercise for this with many people, and they understand quickly how the way you move your body affects how you feel at the moment. If you keep reinforcing a positive and confident state with your body language, the effect will be long-lasting.

Exercise: Changing Your State

Think of something that makes you feel down, but not downright depressed. Maybe someone said something he meant to be funny, but you were humiliated by the “joke.” Even though you forgive the person, every time you think of his remark, you feel a little emotional pain.

Plant that insult firmly in your head. Water it with your feelings of resentment and hurt.

Immediately get up and walk with a bounce in your step and your head held high. Smile at anyone you pass, and if you don’t pass a human being, then smile at your cat.

How do you feel now?

You can’t just walk down a hall and smile at people every time you feel emotionally weak and lack confidence, of course. Another way to accomplish your goal is to assume a power pose. Sisco recalls, “One company hired me to attend a networking meeting in which each of the 40 participants had to stand up for 45 seconds and do a self-introduction. Everyone had T-Rex arms.” Sisco was referencing the fact that everyone’s arms were tucked into their sides so that they looked like the little, dangling arms of a T-Rex.

So while confident words came out of their mouths, their bodies indicated they were not confident. “When your arms are tucked in like that, it’s like you’re giving yourself a little hug.”6 In other words, it’s an obvious self-soothing gesture, a physical way of telling ourselves, “I’m going to get through this; it’ll be okay.”

In contrast, a power pose looks like this:

![]() Your arms are comfortably at your side, with your body open to the person you’re speaking with, and you use the whole arm in making a point.

Your arms are comfortably at your side, with your body open to the person you’re speaking with, and you use the whole arm in making a point.

![]() You’re standing erect with your feet about six to 10 inches apart.

You’re standing erect with your feet about six to 10 inches apart.

It can also look like this: Your arms are up the air, your chin is up, and you have a giant smile on your face. You can do it sitting or standing. It’s the power pose you use in the elevator before you have a job interview, or the power pose you assume in the bathroom before you do a presentation to 200 people.

Does a power pose really make difference to your state of mind, as the exercise suggests? Yes. Unequivocally, yes.

Amy Cuddy is a professor at Harvard Business School whose research on body language focuses both on how we change other people’s perceptions of us as well as how we biochemically can change ourselves. In one of her experiments, she opened with saliva samples of all subjects to determine their levels of the hormones testosterone and cortisol. The higher the testosterone level, the greater the subject’s feeling of power; the higher the cortisol level, the more stress he or she felt. Next, she had some subjects adopt power poses for two minutes and other subjects adopt postures that suggested subservience and weakness. All the subjects were then asked how powerful they felt about a series of items. Next, they were offered the opportunity to gamble. Among those who had adopted the power poses, 86 percent chose to gamble. Only 60 percent of the subjects in the other group chose to gamble. Cuddy calls this a “whopping, significant difference.”7 The final phase of the experiment involved collecting another saliva sample to determine whether or not there was any discernible difference in the levels of testosterone and cortisol. The power posers had an average of a 20-percent rise in their testosterone levels; the low-power people experienced a 10-percent decrease. The high-power people experienced an average of a 25-percent decrease in cortisol levels; the weak posers experienced a 16-percent increase. These dramatic changes occurred after they spent just two minutes in the different types of poses!

My favorite story about the transformational power of positive body language comes from Cuddy’s memorable TED talk called “Your Body Language Shapes Who You Are.”8 When she was 19, Cuddy suffered a serious brain injury in a car accident. When she woke up in the hospital, she learned she had been withdrawn from college and that her IQ had dropped by two standard deviations, or approximately 30 points. Part of Cuddy’s identity was being smart; she had been labeled gifted as a child. She kept trying to go back to college despite people around her expressing their concern by discouraging her from inevitable failure.

Cuddy persevered and graduated from college four years after her peers. With that unlikely success behind her, she began the path toward a PhD in social psychology. This is the rest of the story in her words:

I convinced someone, my angel advisor, Susan Fiske, to take me on, and so I ended up at Princeton, and I was like, I am not supposed to be here. I am an impostor. And the night before my first-year talk—and the first-year talk at Princeton is a 20-minute talk to 20 people, that’s it—I was so afraid of being found out the next day that I called her and said, “I’m quitting.” She was like, “You are not quitting, because I took a gamble on you, and you’re staying. You’re going to stay, and this is what you’re going to do. You are going to fake it. You’re going to do every talk that you ever get asked to do. You’re just going to do it and do it and do it, even if you’re terrified and just paralyzed and having an out-of-body experience, until you have this moment where you say, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m doing it. I have become this. I am actually doing this.’” So that’s what I did.9

The message she now gives to students at Harvard who are similarly struggling is to “fake it until you become it.” Practice the power poses for two-minute stretches and breathe like you own all the air in the world.

Now that you’re relaxed and feeling supremely confident, simply apply Sisco’s 10 techniques and you are well on your way to establishing rapport:

1. Smile with your eyes. It’s the look you give to someone you are genuinely happy to see—a genuine smile with wrinkle lines, not the one that you see many celebrities use on the red carpet. Here’s an example of smiling with the eyes (right).

2. Use touch carefully. Haptics is the study of communication by touch. Researchers in this field have found that students evaluated a library and its staff more favorably if the librarian briefly touched the patron while returning his or her library card, that female restaurant servers received larger tips when they touched patrons, and that people were more likely to sign a petition when the petitioner touched them during their interaction.10 Often when you meet people, you shake their hand. That’s just the beginning. At some point in the conversation, you may want to use a gentle touch on the arm, for example. It’s a physical reminder of the bond that’s forming. Note that in some cultures, this would be inappropriate. Know your audience.

3. Share something with the person about yourself. The discussion of quid pro quo as a conversation motivator in Chapter 4 goes into this a little more. Basically, if you want to know about someone’s job satisfaction, for example, you might volunteer that your boss is a perfectionist who is very difficult to please. The person is likely to feel you’ve divulged a secret and thus will be more forthcoming about his own workplace circumstances.

4. Mirror the other person. People like people who seem to be like them. Be cautious, however, because you do not want to mimic the other person; that will destroy rapport. Mirroring is subtle, such as a slight lean in the same direction as the other person or using an arm position that’s similar. There is a verbal corollary to these kinds of mirroring movements. When you hear where a person is from or what baseball team he likes, you want to look for a connection, such as “My favorite cousin lives there” or “That was my dad’s favorite team, too.”

5. Treat everyone with respect. If you expect to be treated with respect by others, then that’s how you have to treat them. Sisco discussed the emotional challenge of establishing rapport with members of the Taliban who had done horrific things to people. Her job as a military interrogator depended on the ability to connect with them with respect; she had to remind herself, “At the end of the day, they are still human beings. They breathe oxygen just like I do. Every human being on the planet wants to be treated with respect, regardless of who they are or what they’ve done. To get them to talk to me, they have to feel honest respect from me.”11

6. Reinforce trust through your body language. Use open body language, especially as it relates to the three power zones: nape of the neck, naval, and crotch. If you have your three power zones open to people, your body is projecting this message: “I’m open to you. I trust you.”

Consider the effect of the opposite—that is, covering each of these areas. As the photo indicates, there is a definite sense that the person feels either ill-at-ease or suggests that he is closed off from the person he’s with—not perceptions that support rapport-building.

7. Suspend your ego. Show interest when the person tries to tell you how to do something or explains a concept to you. Let him educate you. People like to get on the soapbox. It makes them feel smart and important. This tip, along with the next one, is explored in greater depth in the Chapter 4 discussion of conversation motivators under “Boosting Ego.”

8. Flatter and praise. It’s not a matter of overtly buttering up the person, but rather just pleasantly offering a compliment about her accomplishments or family, for example. If you don’t make someone feel good, why would she invest the time and trust in developing a rapport with you? Compliments energize people.

9. Take your time to listen. And by listen, I mean listen with your body. Lean into the person a little; nod your head at key points. When someone thinks that you have drifted away from the conversation, you’ve lost rapport. As part of your active listening, start using the other person’s words when it makes sense. For example, you have no military background, but your subject is a Navy officer. He talks about ships, not boats. So you talk about ships, not boats. Adopting keywords shows you are paying attention.

10. Get your subject talking and moving. Ask open-ended questions requiring a narrative response. These are questions that begin with an interrogative: who, what, when, where, how, and why. Jim Pyle and I devoted an entire book to the art and skill of using such questions in Find Out Anything From Anyone, Anytime. As a companion to talking, when you move the conversation from one place to another you have set the stage for truly energizing your rapport-building. Remember the reference earlier in this chapter to Hanns Scharff’s technique of taking prisoners for walks in the woods or accompanying them to a trip to the local zoo. If you’re interviewing someone for a job, for example, walk the person from your office to the elevator as you continue to talk. Once a person has had the experience of connecting with you in different environments, the bond between you strengthens.

Going Global With Rapport

Global consciousness is also a significant part of the 21st-century conversation about rapport-building. The following story is from Michael T. Reilly, currently a deputy chief fire marshal in Fairfax County, Virginia, and a reserve special agent in the Coast Guard Investigative Service (CGIS). It illuminates how rapport can be instantly destroyed by a deficiency in cultural sensitivity:

I was stationed in the Middle East, doing some training for the Royal Saudi Police Academy. I was part of a team teaching a post-blast emergency medical response program for Saudi national police officers who were going to be responding to bombings and other acts of violence. One of the classes was on cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and the Heimlich maneuver.

The first problem we had was that we gave them a bunch of Annies, which are training mannequins used for teaching CPR. That was our first mistake. You would have thought I had chopped Mohammed’s head off right there in the office.

Resuscitator Annie [aka Resusci Annie or CPR Annie] has breasts. Touching the manikin’s breast areas is harām—that is, forbidden by Allah. It is a sinful act.

We had to have a Muttawa (religious police) come in and tell the Saudi troops that it was okay to work on the manikin.12

Reilly’s learning about how to connect with his Saudi students continued. What he experienced is extreme, but the rest of us experience versions of this every day. People have experiences that shape their concepts of what is right and what is truth. If we don’t recognize and respect the significance of those experiences, the probability of forging a trusting connection is extremely low.

He was trying to teach one of the dignitary protection officers the Heimlich maneuver, which are abdominal thrusts designed to dislodge food stuck in the trachea that’s causing the victim to choke to death. These are people charged with protecting the lives of the Saudi royal family. The session with Reilly went like this:

We demonstrated the Heimlich maneuver and he said, “I do not need to know this.”

I said, “Yes, you do. If the prince or king has an airway obstruction, you going to need to perform the Heimlich maneuver.”

“No, I would not do that.”

“What do you mean?”

“You do not understand. If I do that and I did not remove the object and the prince or king died, then my head would be cut off the next day.”

I grasped the concept quickly that he would be beheaded if he failed in executing the maneuver. So I took a slightly different approach to teaching. “Suppose one of your children is choking. Wouldn’t you want to know how to save him?”

In straight-faced candor, he said, “I can have another.”13

Reilly learned to remove his judgment from the interaction. He had an acute awareness that respect for the other person’s values and sensibilities held the key to forging a connection with him. Not only that, but Reilly realized that respect for the man’s national pride, cultural heritage, and religious beliefs—everything feeding those values and sensibilities—was essential in rapport-building.

Going Online With Rapport

There are three angles to the discussion of going online to establish and reinforce rapport: online resources that are useful in all forms of rapport building—face-to-face, phone, and written—best practices for building rapport electronically, and rapport-wrecking actions.

Online Resources

Online resources enable you to do three things that support rapport-building:

1. Find out facts about a person’s history, such as previous jobs, education, where he’s lived, what clubs and groups he belongs to (in real life or online), and much more.

2. Use the information you discovered to pinpoint areas where your interests and experiences intersect and/or are in sync. The more a person feels she has something in common with you, the easier it will be to establish rapport.

3. Contact the person in a non-intrusive way, inviting a response to form a connection, but not requiring it in the same way as if you showed up at his office and introduced yourself.

In the discussion of what Hanns Scharff did to forge connections with Allied prisoners of war, I noted that he did his homework about the individuals he intended to interrogate. Social media sites offer you goldmines of information about people so that you can do the kind of homework that helps you strengthen an initial interaction. You can find out enough to make your connection with them can feel personal. You can find out how best to present yourself so that your outreach makes sense to the person, whether that outreach is in writing, on the phone, or in person.

Before approaching someone, you first want to find out what networks he belongs to and what groups within those networks. For example, one of the people I interviewed for this book is David Major, a leading authority on counterintelligence. Before meeting with him, I researched his background on LinkedIn, so I could demonstrate that I cared enough about the interview to know not only what he studied in college (biochemistry), but also to be aware of what boards he serves on (International Spy Museum and Association of Former Intelligence Officers). I also took note that his connections included a number of people that I should probably interview for the book.

Major is not on Facebook. However, another of the key people I interviewed for the book is on Facebook, as well as LinkedIn and Twitter: Lena Sisco. Knowing that we had professional associates in common (through LinkedIn), as well as similar tastes in movies and a love of animals (through Facebook), I had a keen sense of how we might interact. Julio Viskovich, whose expertise is primarily helping people to drive sales with social media, notes that “using social media will allow you to align yourself with your audience, give you a common interest, and allow you to demonstrate value based on your assessment before meeting.”14

But the kinds of searches that yield this worthwhile information can be time consuming as you move from site to site. An online resource that reduces that research time is Nimble, which pulls your contacts into one place automatically. It also provides a dashboard of daily activities across your networks, and you can receive reminders about staying in touch with members of your network—so-called engagement opportunities. As the social media world gets more complex, Nimble is the kind of tool that has a lot of value in understanding and managing relationships.

Best Practices

Long before the World Wide Web linked us to people around the planet, best practices of intelligence organizations, exclusive clubs, and socially adept hosts foreshadowed the kind of actions and information that facilitate rapport-building. These are practices that promote a sense of trust, respect, and consideration.

The historical and anecdotal information about best practices in the upcoming paragraphs illustrates how you can take the same kinds of actions by thoughtfully using social media and other online resources.

Connect with a person, not a number.

Throughout the ages, many clubs have required that one or more current members give their word that a candidate for membership maintains the personal and/or professional standards that the group values. The Freemasons state: “A well-recommended person is one for whom another is willing to vouch.”15 Some organizations insist on an even more intimate connection. For example, when a colleague of mine sought membership in San Francisco’s Olympic Club, a private social club and the oldest athletic club in the United States, the person who vouched for him was asked if he had ever had my friend to his home, which was an essential part of the vetting process.

The core message of the best practice is, therefore, that your designation of someone as a trusted friend, ally, or colleague cannot mean that person is perceived as one of many. Your “club” must be exclusive; a person must meet certain standards to get into it. If people in your circle have reason to believe that, you have leverage with them when it comes to truth-telling.

A lot of people look at Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitters as numbers games. That’s good for some purposes and terrible for others. If you’re thinking about getting a book published, the publisher will take a look at your connections and followers to ascertain whether you seem to have the ability to drive sales of your book. There’s a downside, though, in terms of your perceived value as a connection if you hit high numbers by saying yes to everyone. Keeping the discussion focused on your ability to vouch for someone, or another person’s ability to vouch for you, I’d caution you that having thousands of connections undermines the perception that you choose friends and colleagues carefully. It is not a best practice.

Why? Remember that your ability to establish trust and rapport has to do with how the other person perceives you and how much you have in common, not precisely what you do or who you are. This is why sociopaths with brilliant social skills can be so successful in business, politics, and other fields. They are not trustworthy, nor do they necessarily share interests or values with their target audiences, but they are perceived by them as having what it takes to be a colleague, friend, or desirable leader. Facebook is not very different when it comes to perception, according to the team of researchers who authored “Too Much of a Good Thing? The Relationship Between Number of Friends and Interpersonal Impressions on Facebook,” which was published in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. They concluded: “[J]udgments of social attractiveness are due to similarity of the rater to the target.”16 Given that the average number of friends is around 300, they found evidence to substantiate that the optimum number of friends to inspire a sense of intimacy and genuine connections is about the same. In summary, they said:

This study advances the important finding that socio-metric data such as the number of friends one has on Facebook can prove to be a significant cue by which individuals make social judgments about others in an online social network. This study contributes findings that in the case of social attractiveness and extraversion, individuals who have too few friends or too many friends are perceived more negatively than those who have an optimally large number of friends.17

In short, this is an issue of quality and the right quantity. High numbers of connections may give you the illusion of closeness, but that’s all it is—an illusion.

Use your online resources to help you make people feel special.

There are plenty of historical illustrations of this, with a particularly memorable one coming out of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Polish colonel Ryszard Kuklinski defected to the United States in 1972, and among the important pieces of information he gave the CIA in the next nine years were the secret plans to crush solidarity. Throughout those years, he took enormous risks, jeopardizing his life and that of his family. But from the very first meeting with his CIA handler to his dramatic escape to the West, the CIA took steps to recognize his humanity as well as the value of his contributions.

At his first meeting with Kuklinski, David Forden—code-named Daniel—explained why the CIA was involved and introduced him to the tradecraft that would be part of their operations. He also wished Kuklinski a belated happy birthday, letting him know that the two of them were nearly the same age. The birthday wishes triggered an unexpected outpouring of thoughts and feelings:

Kuklinski grabbed the microphone Daniel had placed on the table and spoke with great emotion and purpose-fulness. He thanked Daniel for his birthday wishes, which had meant a lot to him. On the General Staff, he said, birthdays were rarely celebrated; everyone was too busy. One day, a few years earlier, Kuklinski said, he had told a colleague that it was his fortieth birthday. “For me, it is a certain special moment—in the life of every man—40 years.”

His friend joked cynically, “We’ve already had our drink. Get your ass out of here and back to work!”

Kuklinski laughed. It was typical of how people were treated on the General Staff, he said. “To a man from whom the last juices are sucked out.” Any flicker of emotion or happiness was “extinguished.” He added, “An individual counts nothing in our system.”18

Sites such as Facebook make it easy to remember someone’s birthday, so take advantage of it. Similarly, when you see that one of your LinkedIn connections got a promotion or a new job, congratulate that person. One of my colleagues is also very good about thanking people for endorsing him on LinkedIn, and those expressions of appreciation have paid off for him in new consulting opportunities. All of these ostensibly small gestures strengthen rapport; they potentially expand the number of people who legitimately compose your trusted inner circle.

In conducting interviews for this book, I have learned that people who have these kinds of interactions on Facebook and LinkedIn are much more likely to feel a sense of confidence/trust in those people when they see them face-to-face than if they had not had the online interaction. They tell me that they jump into personal, confidential conversations much more readily than if they had not had the positive online contact.

Apply rules of etiquette to electronic communication.

One of the authors my literary agency represents is a gentleman in every sense of the word. His name is Ira Neimark, the former CEO of Bergdorf Goodman. Since 2005, we have exchanged thousands of e-mails and without fail, he begins with “Dear Maryann” and ends with “Best regards, Ira.” I reply in kind—even if I am pecking out an e-mail on my iPhone. I feel honored, and perhaps even elevated, by his consistent courtesy. And in some way, no doubt subliminal most of the time, I feel as though he has earned my immediate attention on any range of issues. As a corollary, we trust each other.

The seconds that it takes to inject civility and respect into e-mails and texts yield a huge payout in terms of rapport-building. And part of being civilized is not making an assumption that the other person gets your sense of sarcasm, irony, or humor. Your tone of voice cannot be heard in an e-mail or text.

Rapport-Wrecking Actions

When electronic communication puts distance between you and another person, it’s very hard to restore the sense of trust and rapport by using the e-mail or texting. Once the damage is done, you need to go face-to-face or at least have a phone call to add other dimensions of communication, such as tone of voice and non-verbal signals of openness.

With that thought in mind, consider these abuses of e-mail and text:

Relying solely on written, electronic communication like e-mail and text to manage a relationship is a mistake.

Even if you think you have a trusting relationship and really understand someone, it helps to at least phone occasionally or the rapport could weaken to the point of disappearing.

I had what I thought was a great relationship with a book editor to whom I introduced an aspiring author. The editor signed the author and then, three months later, the editor cancelled the publishing contract. I was shocked and sent the editor an e-mail asking what happened.

The note I got back did not strike me as the truth, even though I would have bet this person would never try to deceive me. I tried again via e-mail and got a similar answer, and I still wasn’t satisfied. Something about the response seemed scripted, in contrast to the casual exchanges we usually enjoyed.

I called the editor, and she said that her boss had told her to say that the book didn’t meet the company’s standards, but the truth was that the business was running in the red so she was getting laid off and almost all her projects were getting axed. The e-mails captured the boss’s words, and even the boss’s personality, so my initial sense of being deceived had a foundation.

One phone conversation allowed us to get back on track. We realized what had just happened between us; it was distressing, as we’d become friends over the years. We promised each other that we would never go “all e-mail” again.

And if someone does something nice for you, do not use a texting to say thank you. That mode of expressing gratitude trivializes what the person did for you.

Texting is a valuable tool for spontaneous communication, but it turns ugly when the spontaneity is linked to anger.

This text exchange is real—typos and all—and in the same sequence received and sent; only the names have been changed to protect the identities of the people involved. The text messages took place between Nancy, a friend of mine, and her hair stylist of 10 years, Barb. Barb had also been doing housecleaning for her for the previous year. The hairstylist decided to use a new type of color on Nancy’s hair the evening before she went on a business trip. The next morning, from the airport, Nancy sent her first message of concern:

Nancy: |

Too uniform. Does not look natural. |

Barb: |

U r funny always uniform first day LOL Wait a shampoo or two! |

My not-so-funny friend then called the stylist, who told her to wash her hair with Prell shampoo and baking soda. The situation did not improve.

It seems inconceivable that someone in a customer service business would respond to an earnest complaint with a price increase, but this is what the stylist did. Every time my friend Nancy looked at her phone and read the message, she got angrier. The rapport they had was destroyed. Another factor to consider is that they both live in a small town, and it’s highly likely someone will notice that my friend is now going to a different stylist.

Texting tends to be an unplanned, uncensored exchange, so if strong emotion is present, it will bleed out onto the screen. You have no guarantee that the recipient will glance at a text you typed while feeling grumpy and dismiss it as “Joe’s just in a bad mood.” The next time that person picks up his phone and receives a text from you, the grumpy-Joe text will probably still be there as a reminder that you have a bad side. Whether this occurs in the context of a personal relationship or a professional one, the effect can be corrosive.

Here is the key: Whether you forge a connection face-to-face, over the phone, or online, rapport-building must involve interaction. This is why Facebook, for example, is a useful tool, whereas any “push” communication is not.