CHAPTER

11

Organizational Experiments in Circle Governance

Organizations with a commitment to systemic change and alternative structure may use circle as their self-governance.

Circle’s use as a dynamic, positive force for changing the world is rapidly evolving. In May 2009, Christina attended a two-day conference on Peace and Social Justice Issues sponsored by Catholic Women Religious. In a workshop on emergent social issues offered by Fran Korten, editor of Yes! magazine, she asked those of us in the audience to reflect on three questions:

![]() What did you notice on the fringe of society fifteen years ago that is now in the center?

What did you notice on the fringe of society fifteen years ago that is now in the center?

![]() What do you notice on the fringe now that you hope will move to the center in the next fifteen years?

What do you notice on the fringe now that you hope will move to the center in the next fifteen years?

![]() What are you willing to do to contribute to that happening?

What are you willing to do to contribute to that happening?

Christina walked to the microphone and began talking about the shift in circle work in the fifteen years between founding PeerSpirit, Inc., in 1994, and the conference of eighteen hundred women and men in May 2009. She spoke about circle being a fringe movement reentering society through consciousness-raising groups, through experiences like the California-based Women’s Summer Solstice Camps (1985–1996), through organizations like Women Within International and the Mankind Project, through the Council of Wilderness Guides and the School of Lost Borders, through Ojai Foundation and its teachings in The Way of Council, through John Seed, Joanna Macy, and Pat Fleming’s work with The Council of All Beings. She then spoke about how circle has now taken hold in indicator professions such as education, religion, health care, and the nonprofit sector. “That was our goal,” she said excitedly. “We knew circle would work at the edge—and we believed it was equally needed in the middle.” At the end of the session, people clustered around and talked excitedly of their own experiences with circle, moving from the edge of their lives toward a more central and accepted practice

Circle as Agent of Cultural Shift

What was on the edge fifteen years ago that is now in the middle?

The story goes that the origins of the Polish Solidarity movement started in 1970 when Lech Walesa and a few colleagues began meeting secretly around the docks of Gdansk, preparing to take on their government and through these protests deal with the interference of the Soviet Union in Polish national affairs. A handful of rebels versus the Soviet Union! In September 1980, Solidarity called a national strike based on nonviolent principles. One year later, Solidarity called its own national congress and elected Lech Walesa president of an alternative government, “a self-governing republic.” In 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government elected Walesa the prime minister of Poland. And from 1990 to 1995, he was president of the country he helped liberate: from the edge to the center.

Wangari Maathai, the “Tree Lady of Kenya,” was a college professor of biology when she started responding to the hardships of rural women’s lives by suggesting that women plant trees for food, firewood, and shelter. In 1977, she started the Green Belt Movement, consciously seeking cultural shift. “The planting of trees is the planting of ideas,” she said. “By starting with the simple step of digging a hole and planting a tree, we plant hope for ourselves and for future generations.” Of the first one hundred trees, twenty-eight survived. She persisted, and so did the trees. In 2004, she was the first black African woman and first environmentalist to win the Nobel Peace Prize. By 2008, the Green Belt Movement had planted 38 million trees and began aiming toward one billion new trees. From two dozen seedlings to a greening world; from the edge to the center.

Margaret Wheatley often tells such stories to remind audiences of the power of small, self-organizing groups. She says, “Every story like this I hear begins with the same phrase: ‘Some friends and I started talking. …’” Each of the three organizations whose stories complete this chapter started down the path to cultural shift by a few key leaders entering just such conversations that led to their perceiving their own potential. As a result of these sparking conversations, each organization has embraced a profound underlying question that grounds its exploration:

![]() What if we used circle process in determining how a national board guides the merger of two well-established entities with the intent to think differently about the management of finances and develop a holistic concept of what comprises wealth? (Financial Planning Association)

What if we used circle process in determining how a national board guides the merger of two well-established entities with the intent to think differently about the management of finances and develop a holistic concept of what comprises wealth? (Financial Planning Association)

![]() What if we used circle to restructure the nature of schools and education, starting with our own school? (Ridge and Valley Charter School, New Jersey)

What if we used circle to restructure the nature of schools and education, starting with our own school? (Ridge and Valley Charter School, New Jersey)

![]() What if we brought circle and dialogue into the management of a health care center and into the relationship between health care provider and health care receiver? (True North Health Care Center, Maine)

What if we brought circle and dialogue into the management of a health care center and into the relationship between health care provider and health care receiver? (True North Health Care Center, Maine)

Each of these organizations lives the circle as an administrative form of governance in its day-to-day operation with awareness that incremental progress is a path toward exponential leaps. Every time that the Financial Planning Association national board meets in circle, the Ridge and Valley Charter School refers to its teachers as guides to the children’s learning, and when True North Health Care Center administers itself in circle, a new way is forged: from the edge to the center.

How PeerSpirit Came to the Financial Planning Association

In 2000, the International Association for Financial Planners and the Institute of Certified Financial Planners decided to merge into one association, the Financial Planning Association (FPA), whose primary aim is to promote financial planning and advances in the financial planning profession. Initially, the executive directors of each association became codirectors, and the two boards merged without relinquishing numbers.

Former board president Elizabeth Jetton recalls of that merger:

“The two organizations just glued themselves together with the shared belief that it was time for one association to emerge from the process, but there was no process for that emergence to occur. Our first meeting was at a big conference center with Robert’s Rules of Order, a gavel, and chairs facing a panel of staff and directors. We raised the question ‘Who are we going to be now?’—but there was no way to talk about it in the format of the meeting. It was a very painful year, with lots of facilitators coming and going and a sense that to discover some kind of cohesiveness we needed to get away and talk with and listen to each other. So for the summer board retreat of 2001, we went to Grand Targhee Resort in the Tetons.”

At that time, Guy Cumbie was president of the board, and Janet McCallen was executive director. Guy, Janet, and a subgroup on the board were starting to look at how to develop FPA as a community. However, the internal sense of community in the board had not yet jelled. Jetton continued:

“I don’t even know how it happened, but when we walked into the room at Targhee, the chairs were in a circle, and Meg Wheatley was there to facilitate the board retreat. We didn’t have any circle skills, no principles or guidelines had been laid out, and no one was prepared for the shift. Some of us sensed that the new arrangement of chairs would open up the dialogue, but we didn’t know if the circle was the leadership technique du jour or if it was going to stay. Some people wouldn’t even enter the circle. They just stood behind their chairs with their arms folded in defiance. Meg was a strong facilitator and a needed bridge for us. I remember we talked about how we were all leaders, how we could better engage in dialogue this way, and we did a lot with flip charts and voting by placing paper dots on various resolutions.”

Though FPA had a strong thought leader and an innovative staff leader, it had underestimated the amount of preparation and pre-work required to shift the paradigm of self-governance and create an amalgamated culture out of two highly defined preexisting associations. The board had been to its first mountaintop. The board members left Targhee still in conflict about the efficacy of circle and unsure how to integrate their experiments in collaborative conversation into the national structure. They planned to host a large World Café at their annual meeting scheduled for San Diego, September 12, 2001—a meeting that never occurred.

The board, staff, and meeting planners who had already arrived in San Diego woke on September 11 to watch the terrorist attacks on New York and the Pentagon on TV. “We were grounded together—trying to serve our clients and members in the face of chaos and tragedy,” said Elizabeth. “The timing of the board meeting in the midst of such a shock, the recent experiences of Grand Targhee, and the work of the newly assigned Community Strategic Team may have allowed the board to accept the idea of more collaborative structure for a new way forward. The trust and bonding that occurred during those days when we were stranded far from our homes were profound.” The board leaders then boldly called a series of World Café gatherings to host large group conversations with state chapters1 and had successful experiences with the membership while continuing to struggle with circle process among themselves.

During this time, before we at PeerSpirit even knew they had adopted circle process and were struggling with it, the board members were doing the hard work of pioneering without understanding where to reach for the infrastructure that could stabilize the process. They were trying to invent the infrastructure as they went along. They desired collaboration and the ability to work in circle, if they could only figure out how to make the circle work for them.

In the summer of 2002, Meg Wheatley was again invited to facilitate the summer retreat, and when Janet said they needed help with their circle process, Meg invited Christina to cofacilitate. In preparation, the group read two Peer-Spirit booklets, PeerSpirit Council Management in Businesses, Corporations, and Organizations and Understanding Shadow and Projection in Circles and Groups. Meg and Christina worked to help the board refine its sense of purpose and functionality. PeerSpirit agreements were put in place; Christina served as guardian, Meg served as host, and they helped shape the work of the board and the group process that would serve the work. Christina listened to the accumulated frustration around their process. The board members wanted certain conditions of efficiency to be met before they would commit to circle; without clear agreements trust kept eroding and they had accumulated significant shadow as decisions were getting made (or unmade) in committees, in subgroups, or at the hotel bar late at night and not shared with the whole board. It was decided that Christina would return to their next board meeting in Denver in early November and coach the circle process—after which they would formally vote to proceed with circle or abandon it.

Christina remembers walking into a large, windowless conference hall with forty people (half board members and half staff), sitting in a circle of huge circumference with a bare coffee table in the center and a piece of pine knot—an artifact from the mountain—resting on it. Their talking piece was a hand-held microphone. No one referenced the center. No one knew how to intervene if people went on long tangents, and power struggles were evident around the rim. They had moved the chairs, but they had not shifted the dynamic. They needed to understand and put into language: social container, attachment to center, strong agreements, use of a guardian, clear hosting through agenda items, and agreed ways to make decisions and initiate action. Christina recalls, “We stopped everything and just worked with circle infrastructure, dividing into small groups in the four corners of the room that came back with agreements (see Exhibit 11.1), statements of core beliefs and values, and clarifications of roles for host, guardian, and scribe. As you will note reading these statements, the language is visionary and far-reaching. It provides the outer rim of philosophy inside which the ever-changing board of directors can respond to current need and function.

FPA Board Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

The group instituted thumb voting as a way to get a sense of cohesiveness in a long conversation or to ascertain readiness to make decisions—and soon members were voting on the work of the subgroups. Christina trained the guardian by opening a chair next to her and inviting various people to hold the chime and practice intervening to pause or correct the course of action as the meeting progressed. The next day, the agenda items went smoothly, and when votes were taken, the board members rolled their chairs forward toward the reenergized center and the staff pushed their chairs back to hold the rim and serve as observers. A solid foundation for circle was in place.

The national board formally adopted circle as its governance, and by the next meeting, the supportive structural language they had developed was standing literally at the back of the circle on laminated foam-core placards at the rim. By the next time PeerSpirit interacted with the board, in May 2005, Marv Tuttle had assumed the executive director position, and the board had voted to downsize membership to eighteen members or less to work more efficiently.

Marv speaks easily about the transition:

“I’ve lived through a hundred board meetings in the previous association and now with FPA. I’ve watched our transformation until we can say that circle has truly become our culture on the board. The board members and staff have developed an atmosphere of welcoming contributions, and we feel comfortable with how we have adapted the form. Our national board meetings are usually two and a half days long, and we think of the meeting in half-day segments. We train each other in guardianship by using someone with experience to take the role during intense issues and inviting new people to assume that authority in more routine sessions. Usually, up to five people have the chance to serve as guardian. The chair of the board is the host, and we see the chair as the board’s mentor who is experienced in carrying the wisdom of the group and watching over our process. The president-elect serves as the advocate for moving through agenda items—someone who is familiar with topics and issues and who has more freedom to lead content. These three folks and I sit equidistant from each other in the circle so that we can keep an eye on the whole process. We hold the container.

“In the center, we have a mirrored globe that reflects our faces to one another, a journal with thoughts and messages from previous board members so that our story is always with us, and several placards of inspiring quotes from Einstein and others. We have two talking pieces: a feather for checking in and out and deeper councils and a Koosh ball for tossing when we want to pick up the pace and still use a talking piece.”

Inevitably in an association environment, leadership changes—both in the board and staff—and the contextual understanding of circle and the story of and importance to the organization needs to be sustained. Transferring the commitment and peer training of circle as new board members join the group has been one of FPA’s biggest challenges. Marv explains:

“People come in knowing we have this circle process, but they’ve never actually seen it or experienced it, and we have to help them adjust. What fosters integrity in this situation is the understanding that we are always in circle as a board, even when we leave the hotel—circle is how we treat each other and our relationships and our conversations. There came a time when we were wrestling with our agreements. Folks were not feeling safe in circle. At our 2007 board retreat, it seemed we were wading through unexpressed expectations when we had to make some complex decisions. So Nick (president in 2007 and board chair in 2008) and I went to the Art of Hosting to enhance and broaden the chair’s and CEO’s skills and attentiveness to circle process. Then we were able to lead the board through a process of recommitment and reaffirmation. For me, this was the most intense experience of falling out of practice and potentially doing harm to our integrity.”

Marv regularly speaks to other executive directors and the Colorado association management group about FPA’s use of circle process.

“When I tell them we do three-day board meetings in circle with small groups operating in Open Space and that we do World Café with hundreds of members, they don’t know what to think. Planners tend to be entrepreneurial, go-getters, quick thinkers, and I try to explain that circle teaches us to hold long, sustained conversations that lead to a clear decision point. We have had to hold very substantial conversations about standards in the financial services industry. For example, it took us five years to come to a decision to press a lawsuit—which we won—with the Securities and Exchange Commission. We were clear going into the suit thanks to the long, clarifying, open-ended conversations we had in circle. Sometimes it makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up when we get to a point of understanding our commitment to an issue or each other. You don’t get that in usual meetings.”

In 2009, Merv contacted the PeerSpirit office requesting our return for a “circle tune-up” with the new board. Neither of us was available, so we suggested they invite Martin Siesta, a former board member with training in both circle and the Art of Hosting modalities. This marked a celebrated progression in the transmission of skilled circle leadership: the next generation of teachers now exists within the organization itself.

Also in 2009, the FPA staff conducted a “listening tour” among the state chapters. They are seeking ways to foster a culture of conversation throughout the association. Their goal is to permeate the chapters and demonstrate to their membership that collaborative conversations using circle, World Café, or Open Space will foster thoughtful leadership wherever it is used.

Ridge and Valley Charter School

Ridge and Valley Charter School, grades kindergarten through eight, opened September 8, 2004, with ninety students. It is a free public elementary school located in the Appalachian ridge and limestone valley region of northwestern New Jersey. The curriculum for each grade is offered through an integrated program, Earth Literacy, which includes learning about the natural world and how humans can live in a mutually enhancing relationship with the entire community of life.

In 2003, when a group of dedicated parents were struggling with all the details of land acquisition, state regulations, teacher selection, and ideological priorities, PeerSpirit colleague Sarah MacDougall traveled to New Jersey to offer a weekend training retreat. She found a group of wise, educated, and fairly burnt-out parents and community members. Together they worked to attend to the group’s depleted energetics and further hone the rotating and shared leadership of circle structure to which they were already dedicated.

Parent, founder, and ongoing trustee Kerry Barnett explained:

“When Sarah first came, we were already five years into the process of launching this school. We had been using circle process for all of our meetings because the open communication circle offers was part of what we intended to offer our children. The school is founded on the premise that humanity’s current model of earth exploitation can’t continue, and we want to educate our children for the kinds of sustainable adult lives we believe they will be required to face. Our earth stewardship model includes the values of collaboration, respect for each other and other species, and a spirit of lifelong learning.”

In these first five years of meetings, the group had had to learn about every aspect of launching a public school—from educational curricula and state educational requirements to real estate law and grant writing. Motivated to find an alternative mode of education for her children that would complement the family’s commitment to alternative living at nearby Genesis Farm, Kerry joined the group in 1999 and has been a member of the trustees’ circle ever since. The trustees’ circle is the equivalent of a traditional school board, except that instead of overseeing a district, it oversees only Ridge and Valley.

Another founding and ongoing trustee, Dave McNulty, is a partner in an e-learning, multimedia, and Web production company in Hope, New Jersey, several miles away. “There are few models for precisely what we are trying to do at the school,” he says. “We are determined to build a public institution on a nonhierarchical model. We want to demonstrate that all of us can work together and make decisions, and I have no doubt that we have made better decisions because we have used the circle and PeerSpirit principles.”

“We did not know how hard this would be,” Kerry explains, “or how many areas we would have to become educated in. However, the biggest education for all of us has come in understanding human relations. As trustees, we have worked explicitly in circle, and it is the reason the school opened at all. We developed sympathy, empathy, love, and trust for one another while working hard to create something we all believed in.”

Traci Pannullo, another young parent looking for an alternative to traditional public education for her child, joined the trustees’ circle in April 2004, less than six months before the first group of students was slated to begin. She remembers:

“We had just purchased a facility. Everything was happening really fast. Then those acquisition plans fell through, and we had to scramble to find buildings where the first group of students could meet. A local Presbyterian church camp provided a short-term solution while our long-term facility construction was completed. Kindergarten and first grade met in a log structure, and the upper grades each met in a cabin with bunk beds pushed aside and wood stoves for heat. It was all very exciting and incredibly intense, and the hardships created great bonding.

“In those early trustees’ circle meetings, I felt something energetically amazing going on between us. I could not articulate it at the time, but there was something very calming and grounding about the ritual elements of the circle: holding the talking piece, pausing to gather one’s thoughts, opening with a quote, checking in and checking out—even in the midst of all the chaos of the school’s reality.”

To illustrate this, Traci loves to share the story of one August night at 2:00 A.M., just before school opened. The trustees’ circle was up late doing a final reading of new policies because everything had to be in place in order to legally open the school.

“Even though everyone was exhausted, there was a sense of determination and commitment. The steadfastness of our teamwork came about as a result of the group’s circle work. It was personally transformative for me to experience people working together with such respect and integrity, even in the midst of incredible tension, deadlines, and occasional disagreements. The circle process continually brought us back to the purpose in the center—the pursuit of a common, higher goal.”

In February 2005, all of the students, teachers, and administrators moved into their permanent building located on sixteen acres with beautiful views of the Delaware Water Gap. The campus includes classrooms and offices, organic gardens and fields, solar panels, a greenhouse, and a yurt. It is located a short walk away from the Paulinskill River Trail. Student-built birdhouses, debris shelters, herb gardens, miniature villages, trails, campfire circles, compost bins, solar ovens, artwork, picnic tables, and much more soon enhanced the grounds.

One steady personnel presence throughout has been Nanci Dvorsky, a lifelong explorer of alternative education, organic gardening, and sustainability, who was drawn to contribute to the unfolding story of Ridge and Valley Charter School. By summer 2005, Traci Pannullo had resigned from the trustees’ circle to become the part-time curriculum coordinator. So now there were two women with history, skill, and circle experience keeping the school stable while other personnel structures were sorted.

The trustees’ circle always intended that the school’s administrative coordinator, curriculum coordinator, and academic coordinator would work together as a circle. However, the old paradigm of a traditional principal in charge of operations kept emerging. After three years of unsuccessfully working toward a paradigm shift, the trustees’ circle once again began to map out a leadership team arrangement that more directly reflected the shared leadership model of the school’s charter.

Nanci and Traci, both deeply aligned with the history and heart of the school, were logical choices for the new leadership team. Lisa Masi, founding kindergarten teacher, stepped forward to work with the team and liaison with her fellow teachers (guides) on matters of integrated curriculum and parent relationships. The fourth member of the team is Rowena McNulty (no relation to Dave), who is the differentiated learning coordinator responsible for all special education. With no principal and no superintendent’s office, the challenge continues to be a need for clear definition of work responsibilities in the midst of collaborative dialogue.

Nanci recalls:

“We could not have sustained the group work through the early challenges if we had not had that foundational relationship piece that came from reading Calling the Circle and then having first Sarah and then Sarah and Ann Linnea come and give us ‘tune-ups’ on circle practice. Each time we refocus on circle work, it strengthens what we are doing. It helps us on our own steep learning curve, coming out of our hierarchical training and expectation. And we are still circle novices.

“Even in the charter school movement, we are on the fringe. Most other charter schools in New Jersey are urban. They are working to create a safe haven where inner-city kids can begin to get acceptable test scores. We are mostly working with children who have clothes, food, and a warm house who are lost and wandering in a diff erent yet very real way. They live in a culture that is too often a wasteland of consumerism and media-paced communication—and they don’t fit. If we can raise children capable of working and living in nontraditional ways, maybe the human crisis we’re in won’t be endlessly perpetuated.”

Dave agrees wholeheartedly.

“Ridge and Valley is a complex mirror of an equally complex society. What sustains us as an organization is that we have children who are happy and eager to attend school. Most parents are really on board about creating and growing a school where children are respected, cherished, and able to develop a joy for living successfully in the larger world. The guides are doing stunning things with their students. And now we have a leadership team that is learning to work together.”

Working for their children and on behalf of all children keeps Traci, Kerry, Dave, and Nanci going through trying times. And all four concur that working in circle has created a core dynamic of love, trust, and respect among trustees and administrators. This is the paradigm shift as they see it now: power struggles, shadow elements, and the pressures for the school to meet state requirements are always present and are counterbalanced with the strength of their relationships from years of working through issues in circle process.

People expect to have to battle their point forward in a typical hierarchical setting. Parents come to a school board meeting riled up and ready to fight. At Ridge and Valley, if something is being overlooked, people can slip into an aggressive attitude and abandon the principle of assuming each other’s good intentions. Everyone from children to parents to teachers (guides) to leadership team to trustees is working to understand and implement a circular, rotating leadership way of being, and the learning curve is not always smooth.

Sarah and Ann serve as “on call” consultants who work with Ridge and Valley to help people clear accumulated misunderstandings and refresh circle skills. When they make visitations to coach circle practice, they usually address several issues:

![]() Reminding everyone that circle-based governance is an attitude and practice of consistency—and looking for any relational places where things have gotten gummed up

Reminding everyone that circle-based governance is an attitude and practice of consistency—and looking for any relational places where things have gotten gummed up

![]() Helping people refine the process to fit their needs now, recognizing that an agreement that worked three years ago may not fit today or that they may need to strengthen a line of communication—as between the leadership team and parents—so that all parties know how to get concerns expressed and responded to

Helping people refine the process to fit their needs now, recognizing that an agreement that worked three years ago may not fit today or that they may need to strengthen a line of communication—as between the leadership team and parents—so that all parties know how to get concerns expressed and responded to

![]() Honoring the groundbreaking nature of what they are doing and helping them keep the larger perspective so that the daily trials are held within the visionary choice they have made

Honoring the groundbreaking nature of what they are doing and helping them keep the larger perspective so that the daily trials are held within the visionary choice they have made

Sarah, a former high school biology teacher who did her doctoral dissertation investigating how circle can transform the field of education, speaks to their roles:

“The school is large enough to act as an organization of incredible complexity and is small enough that almost everyone feels a sense of ownership and stake in the outcome. Children are eager for increasing variety in their educational journeys. Parents are advocating for the particular needs of their children. Teachers want increased curriculum support. Administrators are handling the fiduciary responsibilities along with the daily operations and management. And all this occurs within an environment in which roles are being redefined while responsibilities need to be consistently maintained. Collaborative administration and self-governance is not easy. And the longer and more deeply Ridge and Valley lives this shift, the greater their expectations are for themselves.”

Nanci says:

“One of the hardest things about really being a pioneer is that we haven’t had another school to look to for help. We are literally making it up as we go. Now we are established enough that we can begin reaching out to other parents and teachers with a dream and say, we made it, here’s what worked for us, and we have a sound academic curriculum housed in the delights of nature.”

A recent Ridge and Valley graduate was accepted into an elite private high school. She was excited to attend the daylong orientation but came home disappointed in her experience. She reported to her parents that the entire day had been spent in an auditorium listening to speeches, and she had not gotten to know a single other student. She could not understand why they had not done some interactive games and sat everyone in a circle.

In the long run, this will be the great challenge for Ridge and Valley: How will its students translate their early educational experience as they transition into more traditional higher education and the workplace? Will they find in themselves the leadership capacities their parents and guides hope they are grooming them for? Will they find in themselves the courage needed to march to a different drummer? And will they and the community that guides them now be there to call circles of support for building a world modeled and valued in the haven of Ridge and Valley Charter School?

True North Health Care Center

The holistic True North Health Care Center, in Falmouth, Maine, was founded in 2002 as a 501(c)3 nonprofit after a loose association of determined nurses, alternative and complementary practitioners, doctors, Catholic sisters, and technicians met for four years in circle to realize this dream. The center currently consists of a team of dedicated professionals, ranging from physicians to massage therapists, all working in an 8,200-square-foot facility. The facility has ten examination and treatment rooms, a patient resource area with high-speed Internet access, two conference rooms for classes and workshops, and a teaching kitchen where a natural foods chefdemonstrates healthy cooking during weekend workshops. People are drawn here either because they are coping with difficult health issues that allopathic medicine or a specific alternative therapy has not resolved or because they are healthy and want to stay that way.

In the formative years before the clinic, Kathryn Landon-Malone, a pediatric nurse practitioner, came across the first edition of Calling the Circle and introduced the concepts to the group. “We met twice a month at 7:30 A.M. in the basement of Mercy Hospital in Portland, Maine. Parallel growth processes were going on in many of our lives. There was such tremendous energy in those early meetings; we knew that even if we only checked in, our workdays would be different.”

The group dedicated itself to creating a plan for Mercy to launch an inpatient arm of alternative services that the hospital ultimately rejected for monetary reasons. However, this planning circle had become determined to find a way to offer a holistic health care practice to the Portland community. In 2002, using circle as their organizing principle, a broad range of practitioners opened the current center. Medical director Bethany Hays eagerly proclaims, “We use the circle for everything here—our board of directors, our bimonthly meetings with the entire staff, our weekly decision circle. We have found that circle nourishes relationships, and we believe that there is nothing more important than relationships in medicine and health care. Relationships are as necessary as air, water, movement, love, and food. So much of our health care system consists of broken relationships, and circle offers hope to heal this.”

Hays brings over thirty years of medical practice to True North, with a specialty in obstetrics and gynecology. She practices functional medicine, which focuses on primary prevention and underlying causes rather than what she calls “symptom fixes.” Functional medicine uses the patient story as a key tool in diagnosis and treatment—a ready complement to circle.

True North has been able to apply and adapt PeerSpirit Circle Process based on the original book and their own experience. Although Christina has spoken on narrative medicine at several of True North’s conferences, we have not consulted with the group and have celebrated the center’s ability to learn on its own. Several current and former staff members offer circle training to other medical practices and are conducting qualitative and quantitative research on the impact of circle in health care settings.

At True North, circle begins with four deep breaths followed by a round of check-in of varying length, depending on time and agenda. Organizers don’t appoint a guardian unless they know they’re tackling a challenging issue. They use both talking piece and open conversation and seem to organically know when to pick up the talking piece to make sure every voice is being heard. They vote using thumbs up, down, and sideways and decide everything by consensus minus one. Bethany explains:

“I think it’s critical to hear from the people who vote no. We move forward if there is only a single dissent so that one person can’t co-opt the work of the circle. (We do, however, ensure that the circle member who is dissenting feels heard before moving on.) We use the circle to accomplish real work, and we need to stand by our decisions, so if we have two no votes, we keep hashing things out.”

The center currently has twenty-three practitioners, ranging from specialists in energy medicine to three family practice physicians. A staff often supports these practitioners. Over time, the clinic’s team commitment to operating entirely in circle grew unwieldy—especially as the scope and scale of True North’s work had grown. So in 2007, executive director Tom Dahlborg, who came to the clinic from a more traditional career in health care management, helped design a “circle process survey” to gather information on how circle management might be redesigned for increased relevance. Hays explained, “One survey comment pretty much summed things up: ‘Our system is inefficient and cumbersome. There are too many chiefs and not enough accountability. Circle process generally makes more work for staff that are already overloaded.’” So True North, which had based its entire operational organization on circle, began to question the “sacred cow” of circle.

This is a moment of empowerment in a collaborative organization. The founders had designed a structure, lived it, and were experienced enough to redesign it. Tom Dahlborg and Chris Bicknell Marden, director of marketing and development, who both provide support for practitioners—physicians, nurses, technicians, massage therapists, and nutritionists—were members of the longstanding decision circle, where it was decided that the survey results would be tallied and the process reviewed. The decision circle is made up of administrative staff and practitioners who are committed to weekly oversight and confidentiality. Because it handles personnel decisions, it is the only circle not fully transparent. “The decision circle is the place where we have traditionally had the most revealing conversations because a large nucleus of that group has been together a long time and we really trust each other,” explained Chris. In powerful councils, the decision circle asked the hard questions: Do we want to keep using circle? In what ways is it effective? In what ways is it ineffective? What do we keep? What do we let go of? Can we make circle and hierarchy work together?

Kathryn noted that many conversations focused on the importance of the relationship and community-building aspects of circle.

“Circle has taught us how to be better practitioners. As we have developed heart-centered relationships with one another, we are better able to be in ‘reverent participatory relationships’ with our patients. That is the direct result of circle. Because we work consistently in a circle way, we work differently with our funders, vendors, and patients than most health care systems. We are relationship-oriented. We know how to listen. We can elicit the story of a medical history.”

This is not typical language in a health care system. And while highly valued, the practical and business aspects of the clinic needed tending. Chris continued, “We needed a streamlining process behind the scenes. These conversations took us right into our shadow stuff. It was not fun, and we learned some important things.”

Both Kathryn Landon-Malone and Bethany Hays cited the importance of the teaching they had received from Christina when she had addressed the True North conference several years earlier. Responding to questions about how to respond to conflict, Christina said, “When you feel the circle wobble, don’t abandon the form—lean in and trust it.” In the middle of decision circle conversations emphasizing greater time and money efficiency, it would have been easy to blame circle process and make it a scapegoat rather than using circle to find ways to balance the values of relationship with time management, efficiency, and fiscal responsibility.

“I find conflict very challenging,” said Chris. “Some of these meetings I walked into with a knot in my stomach and almost always left feeling relieved. I noticed that dealing with conflict in an authentic and heart-centered way allowed us to get to the heart of the matter quickly instead of getting stuck in personality challenges.”

As the decision circle met week after week in late 2007, a recurring theme was the need for order and efficiency without sacrificing the relational gifts of circle. The key to unlocking the apparent polarity between circle and hierarchy was the idea that the circle and the triangle (hierarchy) were meant to work together. Hierarchy separated from circle leads to isolated leaders making decisions with limited input. Hierarchy combined with circle establishes a collaborative environment where input concerning impact and consequences is gathered, and leaders feel empowered to act by the whole organization.

Using their commitment to “reverent participatory relationship” and the True North circle process, the decision circle listened carefully to its participants over a period of several months. On November 29, 2007, a document titled “Evolution of Circle at True North” was finalized by the decision circle and then approved by all staff and practitioners. A number of changes to the existing system resulted, including the following:

![]() Creation of a “connector circle”

Creation of a “connector circle”

![]() Creation of a leadership triangle consisting of the board, the medical director, and the executive director

Creation of a leadership triangle consisting of the board, the medical director, and the executive director

![]() A clear delineation of existing circle responsibilities and meeting frequencies

A clear delineation of existing circle responsibilities and meeting frequencies

![]() Procedures to balance work time in circle with work time to accomplish key tasks

Procedures to balance work time in circle with work time to accomplish key tasks

![]() Encouragement of staff independence

Encouragement of staff independence

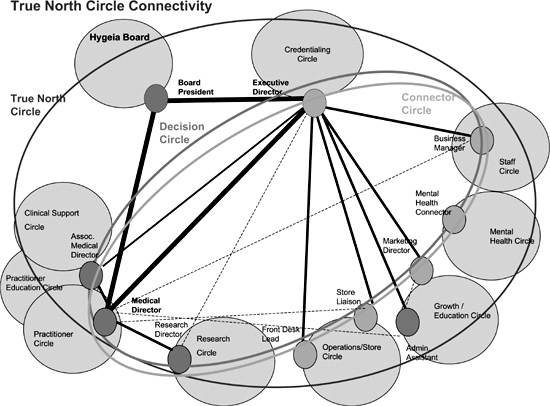

Each of the existing nine circles at True North now has a designated circle connector. Circle connectors are point persons for questions, insights, concerns, and communications. Each of these individuals belongs to a connector circle. A connector at True North may belong to anywhere from two to eight of these circles, which meet anywhere from once a week to three times a year, depending on their function. It may still sound cumbersome to outsiders, but what Dahlborg and the decision circle have done is clarify and structure the kinds of meetings that go on in organizations that usually remain unnamed.

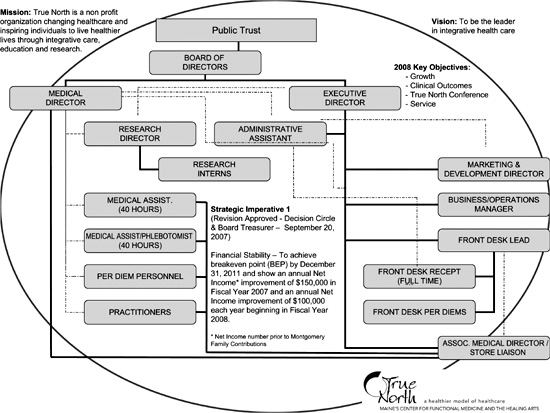

These changes to the existing system can be seen in the True North Circle Connectivity (see Figure 11.1) and the Public Trust Hierarchical Chart (see Figure 11.2). True North’s new organizational charts contain some elements of a traditional system, such as a board of directors working directly with a medical and executive director, with each element of that triangle sharing equal power.

“The fact that we designed two separate charts is significant,” explained Dahlborg. “They say pretty much the same thing, but in different ways for different people. Those who come from a more circular perspective prefer the True North Circle Connectivity diagram, which rounds out the necessary legal, hierarchical connection between our nonprofit board of directors, medical director Hays and practitioners, and myself and support staff. Some members of the True North staff find the Public Trust Hierarchical Chart to be clearer and more precise. We wanted to offer both versions.”

FIGURE 11.1

During the reevaluation process, the decision circle tallied the number of hours each staff member had been spending in circle meetings and the number of hours each staff member would now be spending in circle meetings under the evolved model. Under the earlier system, the yearly cost of wages for staff and practitioners to attend circle meetings came to $492,000. Under the evolved model, costs are $360,000, for a savings of $132,000. “These figures represent our best effort to quantify time spent in meetings,” explained Tom. “This is a useful accounting for any organization, whether meetings take place in a more hierarchical form or in circle as they do at True North.”

FIGURE 11.2

True North has worked diligently to examine its inner workings. The openness of its process is a tribute to the organizers’ genuine belief in the statement from their Web site: “We feel that circle process is healing our multidisciplinary wounds and that it is the container for the momentum of our strong and fearless group to nurture a professional experience that is beyond our wildest dreams (and keeps getting better). The continuous work of the circle has provided us with the most functional place we have ever worked, where we have fun and take risks because of the trust we have in each other and in spirit.”

People at True North acknowledge that looking critically at circle process allowed them to develop an evolved version that better suits “who we are now.” For Tom, the combination of good business practices, continuous process improvement, and a heart-centered approach is what makes True North a powerful place.

Reflections

We have watched these colleagues and many others adapt and refine circle to fit a wide variety of settings and applications and still hold the integrity of PeerSpirit’s basic infrastructure. We made a decision at the start of our work not to trademark our adaptation of such a universal process and social lineage or to certify facilitators. We have practiced honoring our teachers, sources, and circle’s lineage itself and relied on other people’s willingness to do the same as they have carried circle process into their own words and work. We have counted on people practicing at the edge of their confidence and learning as they go—as have we. By and large, this has served us all well. We are delighted to offer so many stories of people who have read about PeerSpirit Circle Process and thought, I can do this. They tried it, and it worked, and they have figured out how to keep working with circle—with and without our engagement. We consider this a huge indicator of the circle’s resilience and capacity to adapt to an ever-changing world.