2

We are all green consumers

Since it was first ignited during the 1970s, the green consumer revolution has been led by women aged between 30 and 49 with children and with better-than-average education. They are motivated by a desire to keep their loved ones free from harm and to secure their future. That women have historically been in the forefront of green purchasing cannot be underestimated. They still do most of the shopping and make most of the brand purchasing decisions (albeit aided by tiny eco-cops riding in the front seat of shopping carts), and they naturally exhibit a nurturing instinct for the health and welfare of the next generation. Poll after poll shows that women weigh environmental and social criteria more heavily in their purchasing decisions than do men. This may also reflect the fact that men in general feel less vulnerable and more in control than women, and thus feel relatively less threatened by news of environmental gloom and doom.

However, with the mainstreaming of green, we are all green consumers now. Yesterday’s activist moms have been joined by teen daughters searching out Burt’s Bees lip balm made from beeswax while their “twenty-something” nephews opt to clean their new digs with Method cleaning products. Husbands boast of higher mileage, fewer fill-ups, and the peppy look of their new Mini Coopers or diesel-powered Jettas that get 50-plus miles to the gallon. The incidence of green purchasing is so prevalent throughout the U.S. population (and I would venture to guess the populations of all countries where greening is prevalent), that consumers need to be segmented psychographically, i.e., by lifestyle orientation and commitment to green, in order to zero in on one’s most appropriate target customers. One such segmentation is provided by the Natural Marketing Institute (NMI) of Harleysville, Pennsylvania. Their research, based on interviews with over 4,000 U.S. adults and entitled The LOHAS Report: Consumers and Sustainability, is excerpted below.

Five shades of green consumers

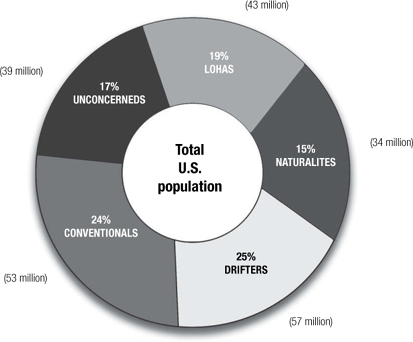

According to the NMI, the vast majority of today’s consumers – a whopping 83% of the U.S. population – can be classified as some shade of green, signifying their involvement in green values, activities, and purchasing. The balance, an estimated 17%, however unconcerned they may be about the planet, can be viewed as inadvertent greens if only because they must abide by local laws requiring green behavior – and the consuming that goes with it, such as recycling. Led by the LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability)1 segment (the deep greens), the NMI’s segmentation of U.S. adult consumers into five distinct and mutually exclusive groups makes targeted marketing of mainstream consumers possible (see Fig. 2.1).

Figure 2.1 NMI’s 2009 green consumer segmentation model %U.S. adults

Source: © Natural Marketing Institute (NMI), 2009 LOHAS Consumer Trends Database®

All Rights Reserved

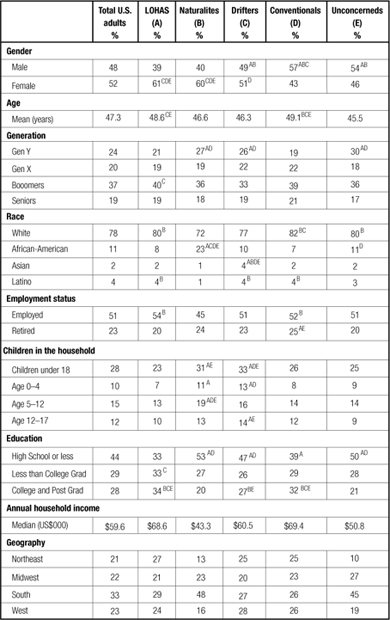

Figure 2.2 Demographic composition of five NMI consumer segments

Capital letters indicate significant difference between groups at 95%. Percentages rounded.

Source: © Natural Marketing Institute (NMI), 2009 LOHAS Consumer Trends Database®

All Rights Reserved

LOHAS

As their name suggests, the LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability) segment represents the most environmentally conscious, holistically oriented, and active of all consumers. Representing 19% of all U.S. adults or 43 million people in 2009, they see a universal connection between health and global preservation and use products that support both personal and planetary well-being. The segment that historically has held the most cachet for sustainable marketers, the typical LOHAS consumer, as depicted in Figure 2.2, tends to be a married, educated, middle-aged female. With the second highest income of all five segments, these consumers tend to be less sensitive to price than the other segments, and particularly so for greener products.

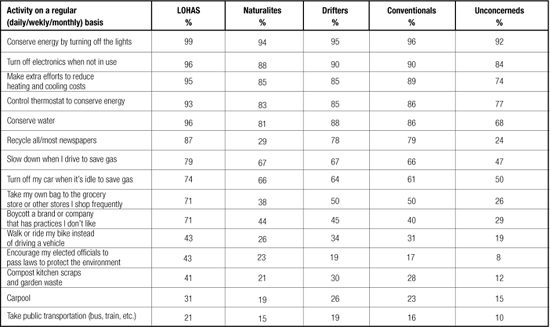

Active at home and in their communities, they readily pluck environmentally sustainable products off the shelf, support advocacy programs for a variety of eco and social causes, and are conscious stewards of the environment. They lead the pack in such behaviors as energy and water conservation, toting cloth shopping bags, and lobbying elected officials to pass environmentally protective laws (see Fig. 2.3). A great consumer for any marketer to snag, they are early adopters of greener technologies. Nearly twice as likely to associate their own personal values with companies and their brands, they are more loyal to companies that mirror their values than their counterparts in other segments. Influential in their communities, they recommend greener brands to friends and family.

Representing a change in the rules for their own purchasing, LOHAS consumers energetically seek out information to ensure the products they purchase synchronize with their discerning environmental and social standards. They scrutinize food and beverage labels, opt for foods with minimal processing, and consume more organically grown produce than any other segment. They also study up on corporate sustainability policies; an astonishing 71% will boycott a brand or company that has practices they do not like, almost twice as high as that of their cousins in other segments. Distrustful of paid media, they will consult the Internet and social among other sources of information. According to the NMI, 14% of the LOHAS segment reports that they purchase hard-to-find greener products online.

Naturalites

About one in six U.S. adults, or 34 million consumers, falls into the Naturalites segment. Assuming a very personal approach to the environment, Naturalites aim to achieve a healthy lifestyle and believe in mind-body-spirit philosophies in addition to the power of prayer. Motivated by buzzwords such as “antibacterial,” “free of synthetic chemicals,” and “natural,” Naturalites are concerned about the harmful effects of chemicals in such products as paint, cosmetics, and food. They are quick to select what they perceive to be safer alternatives for themselves and their children. They are also more likely than any of the other segments (aside from LOHAS) to find it important for their stores to carry organic food, with 19% purchasing natural cleaning products in the past year.

Naturalites see themselves as committed to sustainability, but in reality, they are not as dedicated to green purchasing or behaviors including even recycling as their LOHAS or even Drifter cousins. Nevertheless, Naturalites do want to learn more and become more active in environmental protection and are receptive to education in this regard, especially when there is a personal connection to their health. Demographically, Naturalites are the least likely to be college-educated, and have the lowest incomes. Half of Naturalites live in the South (where recycling is not as prevalent as in other areas) and are much more likely to be African-American.

Drifters

Driven by trends more than by deeply held beliefs, Drifters are the second largest segment of the population, representing 25% of all U.S. adults or 57 million consumers. Younger and concentrated in coastal cities, unlike their LOHAS counterparts they have not yet integrated their values and ethics with their lifestyles. With green considered to be “in,” catch Drifters making the scene at a Whole Foods lunch bar with a trendy cloth sack in hand, or driving a hybrid not to save money on gas, but for how they will look driving about town. They will boycott companies with questionable environmental reputations, but yield to information culled from the media rather than through their own research. Eager to pitch in on simple green activities they understand – they are avid recyclers and energy conservers – they are less apt than their LOHAS counterparts to engage in more nuanced eco-behaviors such as taking steps to reduce carbon emissions.

Demographically, Drifters tend to have larger household sizes with a third having children under the age of 18. Because Drifters are somewhat conscious of the effects that their actions have on the environment, and earn a moderate income, they represent an attractive segment for green marketers. According to NMI, nearly one-fifth think it’s too difficult to consider the environmental impacts of their actions and nearly one-half of Drifters wish they did more to advance sustainability. Marketers who are able to communicate the camaraderie and a sense of belonging that a green lifestyle brings to Drifters will enjoy exceptional returns.

Figure 2.3 Consumer behavior by NMI segment

% of each segment that regularly (daily/weekly/monthly) does the following:

Source: © Natural Marketing Institute (NMI), 2009 LOHAS Consumer Trends Database®

All Rights Reserved

Conventionals

Picture a practical dad directing his kids to pull on a sweater instead of turning up the heat and constantly badgering them to turn off the lights and you get a feel for the Conventionals, the second largest segment representing 53 million consumers who are driven to green for practical reasons. For instance, if LOHAS consumers spend the green for the sake of green, Conventionals will spend more for an ENERGY STAR-labeled fridge knowing it will slash their utility bills.

Characterized by good old Yankee ingenuity or midwestern values, Conventionals are adept at recycling, and they reuse and repurpose things in an effort to reduce waste and pinch pennies. They are aware of environmental issues but are not as motivated to purchase organic foods or other health-related products as their LOHAS cousins for health or environmental reasons. Likely to be males in their mid-to-late forties with the highest incomes of all the segments, 25% of Conventionals are retired, more than other segments, and a sensible group: 45% of them always pay the entire balance on their credit cards every month.

Unconcerneds

In contrast to their LOHAS, Drifter, and Conventional counterparts, 17% of the population representing 39 million consumers, called the Unconcerneds, demonstrate the least environmental responsibility of all the segments. Just over one-quarter will boycott brands made by manufacturers they do not approve of, versus upwards of 40% for their counterparts in other segments; and while 61% say they care about protecting the environment, only 24% recycle. Demographically, the Unconcerneds skew towards younger males living in the South with slightly below-average incomes and lower education levels.

Segmenting by green interests

The rules for addressing the fears of green consumers just got tougher and more complicated. Whereas their counterparts in an earlier day fretted over a rather short list of eco issues topped by clean air and water, recycling, and conserving energy, today’s green consumers fear a much wider range of environmental, social, and economically related ills that include carbon emissions and global climate change, fair trade, and labor rights. No one, of course, has the mental and psychological bandwidth, time, or resources to act on all of these issues. So, even the most eco-aware consumers tend to prioritize their environmental concerns, making it necessary to further divide green consumers into four sub-segments characterized by specific issues and causes: resources, health, animals, and the great outdoors. My colleagues and I at J. Ottman Consulting derived the segmentation depicted in Figure 2.4, with further depth provided in Figure 2.5, from empirical evidence, and offer it as a supplement to the NMI segmentation described above to help you add relevance and precision to efforts targeting the deeper green consumers.

Figure 2.4 Segmenting by green interests

Chart: J. Ottman Consulting, Inc.

Figure 2.5 Segmenting by green interests: in depth

Chart: J. Ottman Consulting, Inc.

Resource Conservers

Resource Conservers (author included) hate waste. Wearing classic styles that last for years, they can be spotted carrying canvas shopping bags and sipping water from reusable bottles. They take their used printer cartridges and electronics to the drop-off center at Best Buy. Once avid newspaper recyclers, they switched to online news services long ago. At home, they reuse their plastic food storage bags and aluminum foil. Ever watchful of saving their “drops” and “watts,” they install water-saving toilets and showerheads and faucet aerators. They shun over-packaged products, knowing they will cost them more in “pay as you throw” municipal waste systems. They’ve swapped their incandescent lamps for CFLs long ago, and they plug their lamps and appliances into power strips, allowing them to save more watts while at work or during a weekend away.

Given the means to do so, they buy home composters to process food waste and install solar panels to save money on electricity. Resource Conservers relish the financial savings that result from these behaviors (it makes them feel smart), and share their experiences with their friends and family to help cut down on more waste. Organizations such as Green America and Center for the New American Dream keep them supplied with ever more tips on eliminating waste.

Health Fanatics

The rule of thumb for Health Fanatics is the consequences of environmental maladies on one’s personal health. These are the folks who worry about sun-induced skin cancer, fear the long-term impacts on their children’s health from pesticide residues on produce, and perk up to news articles about lead and other contaminants in children’s toys and school supplies. Health Fanatics apply sunscreen, pay a premium for organic foods, non-toxic cleaning products, and natural pet care. Catch them bookmarking websites such as the Ecology Center’s HealthyStuff.org and HealthyToys.org to keep abreast of the latest on toxic substances in such recently spotlighted products as school supplies, car seats, toys, automobiles, and pet products.

Animal Lovers

As their name suggests, Animal Lovers are passionate about all animals, whether it be their own pets or those in shelters, as well as those in the wild. Likely to be vegetarian or vegan, Animal Lovers are committed to a proanimal lifestyle. They belong to People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), boycott tuna and fur, and only buy products labeled as “cruelty-free” (not tested on animals). They perk up to news stories featuring animals in need, whether it be manatees or polar bears in faraway sites to strays in their neighborhood, and are most likely to volunteer at the local animal shelter. Out of concern for marine life, they eschew plastic bags. This group would favor the cause-related campaign currently being run by Dawn dishwashing liquid, discovered to be an excellent cleaner of oil-soaked wildlife.

Outdoor Enthusiasts

Outdoor Enthusiasts love the outdoors and spend much of their time actively engaged in such activities as camping, “bouldering” (rock climbing without the aid of ropes), skiing, and hiking. They vacation in national parks and enjoy reading about natural destinations around the world. Outdoor Enthusiasts are also actively involved in such organizations as the Sierra Club and the American Hiking Society, which preserve the pristine spaces they value so highly. Whether it’s purchasing Dr. Bronner’s castile soap to reduce the impact of washing dishes while camping, or reusing bottles and bags to avoid littering the trail, Outdoor Enthusiasts are serious about minimizing the environmental impact of their recreational activities. Their new purchasing criteria includes outdoor gear made from recycled materials, such as Synchilla PCR polyester from Patagonia, Timberland’s Earthkeepers boots, and reusable water bottles from Klean Kanteen.

Green consumer motives and buying strategies

Although they express their environmental concerns in individual ways, all green consumers, no matter how “deep” or “light,” are motivated by universal needs (see Fig. 2.6) that translate into new purchasing strategies with implications for the way authentic sustainable brands are developed and marketed.

Figure 2.6 Green consumer motives and buying strategies

Chart: J. Ottman Consulting, Inc.

Take control

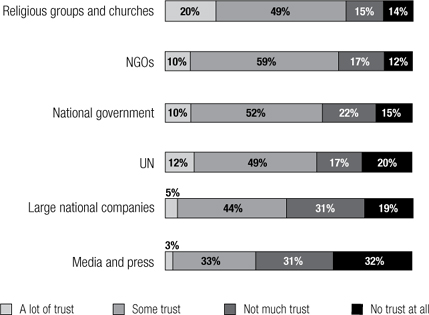

At least one fundamental rule of green consumerism has not changed and likely will not: consumers are looking to control a world they see as spinning out of control. Driven zealously to protect their health and that of their families, sustainability-minded consumers take control in the marketplace, scrutinizing products and their packaging and ingredients with a vengeance; as an added precaution, they also note the reputations of product manufacturers for eco and social responsibility. A key reason consumers are taking things into their own hands is because they tend not to trust manufacturers or retailers – the historical polluters – to provide them with credible information on environmental matters. (see Fig. 2.7).

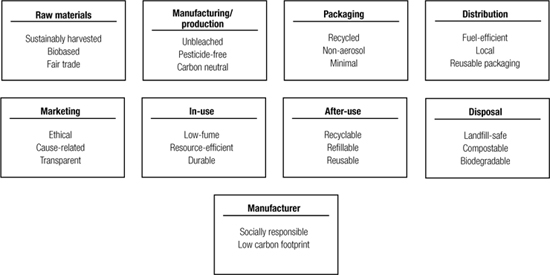

Today’s consumers are doing more at the shelf than just checking prices and looking for familiar brand names. They turn over packages in search of such descriptors as “pesticide-free,” “recycled,” and “petroleum-free.” As depicted in Figure 2.8, the various buzzwords that consumers now use to guide their decision-making represent every phase of the product life-cycle. This suggests that, momentously, while such attributes as performance, price and convenience – once the only things consumers considered when shopping – continue to be important, today’s consumers now want to know about the specifics of a product’s full panoply of green bona fides such as where raw materials were procured, how a product was manufactured, how much energy is required during use, and whether a product and its packaging can be safely disposed of. Remarkably, as a result of green as well as social concerns (e.g., child labor, fair trade), today’s shopping agendas now encompass factors consumers can’t feel or see!

Figure 2.7 Whom do consumers trust for information on global warming?

Source: Globescan report on issues and reputation, USA, 2009. Reprinted with permission

Figure 2.8 also references manufacturers – for good reason. Reflecting the deep-seated loyalties of the LOHAS segment, according to the new rules of green marketing, sustainability-aware consumers now look to see if branded product manufacturers can be trusted for eco and socially conscious practices. Consumers are asking such new questions as: Do they treat their workers well? Pay fair wages? Have a low carbon footprint? If the answers are “yes,” the vast majority of consumers claim they will “pro-cott” or reward such companies. In a 2008 survey, 57% of respondents said they were likely to trust a company after finding out that it is environmentally considerate, and 60% said they were likely to purchase its products.2

Manufacturer (and retailer) reputations for environmental and social responsibility are also critical to consumers’ purchasing decisions in another important way. In the absence of information on the package or shelf identifying a specific product as environmentally responsible in one way or another, today’s consumers defer to their perceptions of a manufacturer’s or retailer’s eco and social track records as de facto eco-labels. The fact that there are so many corporate ads with green themes suggests that business leaders recognize this new reality and are responding accordingly.

Figure 2.8 Green purchasing buzzwords

Chart: J. Ottman Consulting, Inc.

As discussed in Chapter 1, following in the tradition of the Baby Boomers who first boycotted companies that invested in South Africa (and hence enabled apartheid social policies), today’s greener and social-leaning consumers will also boycott suspected polluters, so a questionable reputation for environmental and social practices can also drive consumers away at the shelf.

Get information

Yesterday’s consumers cared mostly about a product’s performance and price. To help them take control of a world they increasingly see as risky, today’s consumers are asking more penetrating questions. They are finding the answers offered in plentiful supply from a broad array of sources. For example, eco-shoppers can now consult any number of trusted environmental groups, including Green America and Center for the New American Dream. They can log onto favorite Internet sites and get the answers to frequently asked questions such as “What’s all the fuss about bamboo?” and “What are some ways that I can save energy in my home?”3 Consumers can also link to any number of other electronic sources, too, including the very detailed GoodGuide.com website and iPhone application for a peek into the health, environmental, and social impacts of over 70,000 food, toys, personal care, and household products; scores reflect data from nearly 200 sources, including government databases, nonprofits, academia institutions, and scientists on the Good Guide staff.

However, not all of this information is consistent, and consumers are having trouble sorting through it in their quest to tell the greener products from their “brown” counterparts, and find out which products and packages can be recycled or composted in their community. Confusion and distrust are setting in, and the reasons are understandable and many: greener alternatives don’t always sport eco-sounding brand names – how can consumers tell by its name that the Method line-up of cleaning products may be greener than Palmolive or Mr. Clean? Alternative cleaners such as baking soda and vinegar may be even greener than Method but are not labeled as such.

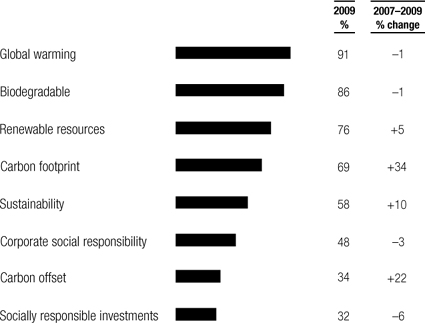

As will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 7, today’s greener consumers seek out trusted eco-labels such as ENERGY STAR and USDA Organic. In fact, at last count, there are more than 400 eco-labels and certifications in existence. However, only a small percentage of greener products actually carries an eco-label, and if they do, there’s no guarantee that consumers will recognize or understand it. As depicted in Figure 2.9, awareness is high for such terms as “global warming” and “biodegradable,” but falls off for newer concepts such as “carbon offset” and “socially responsible investments.”

Figure 2.9 Consumer awareness of environmental terms

% U.S. adult population indicating which of the following terms they are aware of:

Source: © Natural Marketing Institute (NMI), 2009 LOHAS Consumer Trends Database®

All Rights Reserved

Making things worse, sometimes labels can be misleading – or even wrong. Products and packages marked “biodegradable” or “compostable” may be compostable in municipal composting programs, but may not in fact be compostable in backyard composters; those marked “recyclable” may not in fact be recyclable in one’s own community if no facilities exist. (Some of this information is the result of intended or unintentional “greenwashing” by businesses looking to put their best green foot forward. See Chapter 7 for more details about greenwashing.)

Although environmental concern runs high and consumers say they are trying to educate themselves, there are still many issues that they don’t fully comprehend. For instance, most consumers – and even many well-intentioned green marketers – still believe that anything “biodegradable” simply “disappears” – and will even do so in a landfill – rather than decomposing into soil or other nutrients under controlled conditions in a municipal composting facility, when the truth is that trash in landfills is simply entombed.

Make a difference/alleviate guilt

With the world seen as spinning out of control, green consumers want to feel that they can make a difference either as single shoppers or in concert with all the other users of the products they buy. Acutely aware of how humans are compromising their own health and that of the planet, an increasing number of consumers are now reassessing their own consumption and asking, “Do I really need another widget?” For those looking to pitch in, the mantra becomes, “What can I do to make a difference?” This is called “empowerment,” and it underlies such bestsellers as 50 Simple Things You Can Do to Save the Earth, the groundbreaking book that was revamped in 2006. It is now joined on the shelf by It’s Easy Being Green: A Handbook for Earth-Friendly Living; Gorgeously Green: 8 Simple Steps to an Earth-Friendly Life; and The Lazy Environmentalist: Your Guide to Easy, Stylish, Green Living. And they’re watching new television shows on cable such as those produced by Animal Planet, The Science Channel, and National Geographic Channel.

Electronically inclined consumers are also linking to other greens via social networks such as MakeMeSustainable.com, Care2.com, Zerofootprint. net, Carbonrally.com, Change.org, Celsias.com, and Worldcoolers.org. Care2.com, for instance, has a Care2 Green Living section and the Care2 News Network where members can post the latest green news stories.

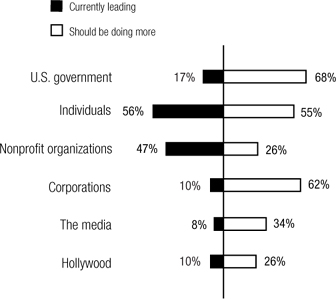

As demonstrated in Figure 2.10, over half (56%) of consumers believe they are doing their bit to protect the environment and indeed perceive themselves as leading other societal groups in this regard, especially government and business. Yet a nearly identical amount (55%) think they should be doing even more – a sentiment that has been trending upward. Consumers’ need to make a difference stems as much from a desire for control as from a corresponding need to alleviate guilt, so their greener purchases can make aware consumers feel good about themselves.

Figure 2.10 Who should be doing more?

% U.S. adult population stating the following organizations are either currently acting as a leader in protecting the environment or should be doing more:

Source: © Natural Marketing Institute (NMI), 2009 LOHAS Consumer Trends Database®

All Rights Reserved

Maintain lifestyle

The environment may be on every consumer’s shopping list, but it’s rarely at the top – for a very understandable reason. Greener products still need to be effective, tasty, safe, sanitary, attractive, and easy to find in mainstream outlets – just like the “brown” counterparts consumers have been dropping into their shopping carts for decades. Although they are concerned about the planet, at the end of the day, shoppers of any stripe, green or not, will – and should – always prefer the laundry detergent that gets their clothes clean over the one that simply promises to “save the Earth.” So it’s imperative that, to be successful, sustainable brands deliver on performance, and why new entries from established brands (e.g., Clorox GreenWorks) perceived by consumers as treading lightly will always win the green day over the proverbial “Happy Planet” brand from an unknown entity.

Despite recessions that bring them back to stark reality, American consumers have been traditionally loath to save for a rainy day, preferring to spend today on short-term gains and pleasures. The same holds true for the environment. Consumers in general are more involved in buying products that will save them money or protect their health today, rather than seeking products that can ameliorate “big picture” issues such as global warming.

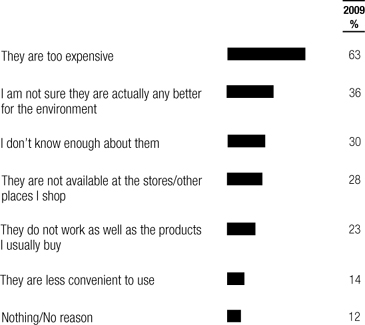

Similarly, it is not surprising that price tops the list of barriers to green purchasing (see Fig. 2.11). Likely sharing this with many types of products (most consumers cannot afford to pay premiums for any products, green or not), resistance to paying a premium for green is exacerbated by the facts that many greener products rely on untested materials, ingredients or technology, have unfamiliar brand names, and, in general, carry perceptual baggage left over from the 1970s when many greener products didn’t work. So ensuring that products work as well as conventional ones, while pricing competitively with alternatives or justifying a premium price with a compelling value proposition, is the name of the game when attempting to meet the needs of the new mainstream green consumer.

Figure 2.11 Barriers to green purchasing

% U.S. adults indicating each of the following prevents them from using environmentally responsible products and services:

Source: © Natural Marketing Institute (NMI), 2009 LOHAS Consumer Trends Database®

All Rights Reserved

Despite the aforementioned, are there times when consumers will pay a premium for green? The answer to this $64,000 question of green marketing is a resounding “Yes!” Consumers will pay a premium if they know a product will save them money. That’s why CFLs are flying off the shelves at Wal-Mart despite their significant premiums over 75¢ incandescent bulbs, and why Americans state they are three times more likely to pay more upfront for energy-efficient electronic equipment than they are to pay less for an energy-guzzling model upfront.4 Consumers will also spend more for their health. Organic. Natural. PVC- and BPA-free. These are the reasons why sales of organic foods and clothing, natural personal care and pet care, and green cleaning products are growing so dramatically.

Lastly, consumers need to believe that brands are genuinely attempting to be more sustainable, a challenge for marketers with implications for education and efforts with the goal of establishing credibility for their messages, discussed throughout this book.

Look smart

It’s the early 21st century. Green is trendy, and as such is part of many consumers’ identity projection. There is a cachet in being green. Green is cool. Celebrities are into sustainability, and the fashionistas enjoy making stylish new clothes out of organic cotton, recycled soda bottles, and other hot materials perceived as greener. Method’s teardrop-shaped bottle and the now iconic Anya Hindmarch “I’m not a plastic bag” reusable tote help outwardly focused Greens (read: Drifters, see above) project their values. Even with record levels of concern over climate change, a study of Prius owners conducted in 2007 found the number one reason why they bought their vehicle was “because of the statement it makes about me,”5 rather than high fuel economy or lower emissions.

Environmental concerns have found their way into consumers’ shopping decisions, and, in turn, are affecting all areas of marketing. Manufacturers and marketers looking to cater to aware and active consumers must adopt a new paradigm for green marketing, detailed in the next chapter.

The New Rules Checklist |

Ask the following questions to assess the environment- and social-related issues that affect your products, branding, marketing, and corporate reputation.

![]() Which segment(s) do our consumers fall into? Which consumer segment(s) likely represent the best target audience for our new sustainable brand?

Which segment(s) do our consumers fall into? Which consumer segment(s) likely represent the best target audience for our new sustainable brand?

![]() What are the chief environment-related interests of our consumers? Are they motivated most by issues such as health? Saving resources? Protecting animals? Enjoying the outdoors and wildlife?

What are the chief environment-related interests of our consumers? Are they motivated most by issues such as health? Saving resources? Protecting animals? Enjoying the outdoors and wildlife?

![]() What are the chief environment-related behaviors of our consumers?

What are the chief environment-related behaviors of our consumers?

![]() To what extent are our consumers likely to read labels? Take preventive measures? Switch brands or stores? Buy greener alternatives that fit their lifestyle? Buy “conspicuous” green goods?

To what extent are our consumers likely to read labels? Take preventive measures? Switch brands or stores? Buy greener alternatives that fit their lifestyle? Buy “conspicuous” green goods?

![]() To what extent are our consumers actively using the Internet to find environment-related product and corporate information?

To what extent are our consumers actively using the Internet to find environment-related product and corporate information?

![]() Which product-related life-cycle issues concern our consumers? Raw materials? Manufacturing? Packaging? In-use consumption? Disposal?

Which product-related life-cycle issues concern our consumers? Raw materials? Manufacturing? Packaging? In-use consumption? Disposal?

![]() To what extent are our consumers willing to boycott or pro-cott our own company’s brands?

To what extent are our consumers willing to boycott or pro-cott our own company’s brands?

![]() To what extent do our consumers believe that they should be doing more to help the environment? In what ways might they want to express this environmentalism?

To what extent do our consumers believe that they should be doing more to help the environment? In what ways might they want to express this environmentalism?

![]() What can we learn for our brand from all the various ways that environmentally conscious consumers act on their concerns?

What can we learn for our brand from all the various ways that environmentally conscious consumers act on their concerns?