7

Establishing credibility and avoiding greenwash

In 1990 Sam Walton promised that Wal-Mart would reward the Procter & Gambles and Unilevers of the world with special shelf talkers (the signs that appeal alongside a given product), if they could prove that their products had greener features. Respond they did, and soon Wal-Mart’s shelves were emblazoned with all sorts of messages about the greener features of various products including dubious ones such as household paper towels where the cardboard core was made of recycled content but not the paper towels. Not surprisingly, environmental activists called the effort a sham, on two counts: the features had been there all along, so no real progress was being made, and the presence of one green feature didn’t necessary mean a product was green overall. This example and others like it represented the very first, likely unintentional, case of greenwashing, and it set the stage for new standards of eco-communications firmly rooted in genuine progress and transparency.

Greenwash!

With green awareness now squarely mainstream, many companies cater to newly eco-aware consumers by launching products and services that may, intentionally or not, be less than legitimately “green.” The popular term for such activity is “greenwashing.” Coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld to criticize hotels that encouraged guests to reuse towels for environmental reasons but made little or no effort to recycle waste, accusations of greenwashing can emanate from many sources including regulators, environmentalists, the media, consumers, competitors, and the scientific community, and it can be serious, long-lasting, and hugely detrimental to a brand’s reputation. With an eye toward making headlines and creating an example for everyone else to heed, advocates tend to target the most trusted and well-known companies. BP, for one, received heaps of criticism on launching its $200 million Beyond Petroleum campaign touting its commitment to renewable energy which, in fact, represented less than 1% of total global sales; and that criticism was only compounded by the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, an estimated 18 times the size of the epic Exxon oil spill in Prince William Sound in spring 1989.

Bill Ford Jr.’s reputation – and that of his family’s venerable company – was tarnished when as chairman of the Ford Motor Company he was unable to fulfill his pledge to build greener cars and follow through on an otherwise laudable Heroes of the Planet campaign. Instead, with the company falling on hard times, he bent to the collective will of senior associates who advocated continuing to crank out gas-guzzling SUVs – and wound up paying dearly for the consequences.1 Relatedly, in the summer of 2008 General Motors got flack from advocate bloggers for announcing plans to “reinvent the automobile” while continuing to manufacture perhaps the most environmentally unfriendly car on the planet – the soon-to-be-defunct Hummer.2 Meanwhile, its Chevrolet division compounded the PR trouble by running ads heralding a “gas friendly” Volt electric car that was not yet in production.

Greenwashers: consumers are on to you! According to a survey conducted in December 2007 at the UN Climate Change Conference, nearly nine out of ten delegates and participants agreed with the statement, “Some companies are advertising products and services with environmental claims that would be considered false, unsubstantiated, and/or unethical.”3 In January 2007, British Telecom found only 3% of UK consumers think businesses are honest about their actions to become more environmentally or socially responsible, with 33% believing businesses exaggerate what they are doing.4

The risks of backlash are high. Using resources and energy and forever creating waste, no company and no product can ever be 100% green. Corporate efforts hinting at aspirations to be green often attract critics. And warm-hearted depictions of furry animals that strike emotional chords with consumers may simultaneously incite the wrath of environmentalists (another reason to lead with primary benefits!). Among other credibility hurdles, consumers perceive that it is not in industry’s interest to promote environmental conservation. After all, industry has a track record of unfettered pollution, and consumers think planned obsolescence was invented by industry to ensure growth; in fact, many people accuse marketers of creating ads that make consumers buy what they do not need.

Advocates often maintain that heavy polluters have no right to tout green initiatives, however admirable. So if you are in the petroleum, chemical, or mining industries, your green attempts, no matter how sincere, may not be viewed as such. Consider the case of the Washington Nationals’ new ballpark. It opened for the 2008 season as the first major baseball stadium to earn LEED certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. This was great news for the team and their fans, but not so for the sponsor ExxonMobil. When environmentalists were quick to object to prominent Exxon billboards throughout the park, Alan Jeffers, a spokesperson for Exxon lamented, “We get criticized for not doing enough for the environment, and then get criticized when we do run an environmental campaign.”5

To complicate matters, there are no clear-cut guidelines for environmental marketing. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued “Green Guides” in 1992; however, since they were last updated in 1996, new terms such as “carbon footprint” and “carbon offsets,” and “sustainable,” have come into the picture. These Guides are in the process of being updated; meanwhile, without fresh guidelines even the best-intentioned green marketers risk making erroneous claims in these and other unaddressed areas.

A word of caution. The Internet is making the stakes higher now than ever before. According to the new rules, media attention to greenwashing has grown with the launch of environmental news websites such as Grist.org, Treehugger.com, Worldchanging.com – and thousands of 24/7 green bloggers and tweeters. Greenwashing even has its own website, greenwashingindex.com. Founded in 2007 by the EnviroMedia agency in collaboration with the University of Oregon, greenwashingindex.com lets visitors rate the authenticity of green marketing claims using “Greenwashing Index Scoring Criteria.” Consumers can read greenwashing news and submit ads to be evaluated by others. Recent marketing campaigns spotlighted on the site include easy-Jet, who claimed that flying their airline generates less carbon dioxide than a typical airline or even driving a passenger car; Monsanto, the giant producer of genetically modified seeds, who pledged to practice sustainable agriculture; and Fiji bottled water claiming that “every drop is green,” despite the fact that water is shipped thousands of miles across the sea compared to tap water which is readily available.

Tired of hearing the term “green fatigue”? It’s a new phrase being used to describe consumers who feel inundated by green marketing buzzwords and a dizzying array of all things green. As a result, they have trouble separating genuine progress from just another green gimmick. The risk of greenwashing and green fatigue from the deluge of advertising claims and green PR pitches is that it can unintentionally create skeptical consumers out of a general public short on facts, and this directly impacts even the best-inten-tioned organizations, tangibly and intangibly. Being perceived as a green-washer can represent a direct hit on corporate trust and credibility and ultimately hit the bottom line, either from reduced revenues or depressed market share when disillusioned customers shift their purchases to more trustworthy competitors.

Much can be done, however, to avert the risks from greenwashing. Start with well-crafted sustainable branding and marketing plans that reflect an understanding of the target audience’s needs. Make sure your products and services are greened via a life-cycle approach (see Chapter 4). And engage and educate potential users to consume responsibly. Thankfully, powerful strategies exist to establish credibility and minimize the potential for backlash. The place to begin is inside one’s own organization.

Five strategies for establishing credibility for sustainable branding and marketing

Follow the strategies discussed below to establish credibility for your green marketing campaign and minimize the chance of it being dubbed “greenwash.”

Five strategies for establishing credibility for sustainable branding and marketing

1. Walk your talk

2. Be transparent

3. Don’t mislead

4. Enlist the support of third parties

5. Promote responsible consumption

1 Walk your talk

Companies that are strongly committed to sound environmental policies need not apologize for failure to achieve perfection. Consumers understand that the greenest of cars will still pollute, the simplest of packaging eventually needs to be thrown away, and the most energy-efficient light bulbs will consume their share of coal, gas, or nuclear energy at the power plant. Thwart the most discriminating of critics by visibly making progress toward measurable and worthy goals, communicating transparently, and responding to the public’s concerns and expectations. Companies that are in the vanguard of corporate greening have many of the following attributes in place, and are consequently the most able to take advantage of the many opportunities of environmental consumerism.

A visible and committed CEO

To successfully develop and market environmentally sound products and services, one must adopt a thorough approach to greening that reaches deep into corporate culture. With consumers scrutinizing products at every phase of the life-cycle, corporate greening must extend to every department – manufacturing, marketing, research and development, consumer and public affairs, and even to suppliers who provide the raw materials, components, and packaging. Only a committed chief executive with a clear vision for his or her company can add the necessary weight to the message that environmental soundness is a priority.

The need to start with – and communicate the commitment of – the CEO cannot be overstated. CEOs can forge an emotional link between a company and its customers, acting as a symbolic watchdog who supervises corporate operations and ensures environmental compliance. That’s why CEOs of such environmental standouts as Interface, Patagonia, Seventh Generation, Timberland, and Tom’s of Maine all maintain high profiles; Tom and Kate Chappell historically included a signed message to consumers on each their natural personal-care products. Jeffrey Hollender maintains a blog on Seventh Generation’s website entitled “The Inspired Protagonist.” By projecting a personal commitment to the environment, CEOs win their stakeholders’ trust. Such leaders are especially believable because they are perceived as having a personal stake in the outcome.

CEOs who are not seen as watching the shop run the risk of derision by corporate watchdogs. Taking Apple to task for not doing as much as competitors to green their products and company, Greenpeace created a special “Green My Apple” campaign and website, encouraging Apple customers to voice their concerns. In May 2007, Steve Jobs, CEO of Apple, responded with a letter entitled, “A Greener Apple.” In it, he detailed his company’s efforts to remove toxic chemicals from its products and expand post-consumer recycling. He apologized for keeping consumers and investors in the dark regarding Apple’s plans to become even greener and promised to communicate such efforts to the public in the future.6

Empower employees

The best-intentioned CEOs will only be as effective as their employees. Only when employees are on top of the issues and given the authority to make changes will greener products be launched and sustainable practices be put into place. Employees have many reasons to get concerned about green issues. Relying on secure jobs for their livelihoods, they have a direct stake in their company’s success.

However, just like consumers, employees need to be educated about environmental issues in general, and of course about the specifics of their company’s processes and brands. Many companies regularly enlist outside speakers to bring employees up to speed about trends in demographics, technology, and the economy; now, speakers, like myself, devoted to environmental specialties meet the demand for talks on climate change, clean technology, and green consumer behavior. Some companies have set up intra-company blogs or wikis to help employees identify ways to get involved, locate other colleagues with similar interests, and make a difference in their communities. Burt’s Bees gives employees money to offset home energy use and Bank of America subsidizes employee purchases of hybrid vehicles.

Be proactive

Most big businesses adhere to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO)’s ISO 14001, a voluntary international framework for a holistic strategic approach to an organization’s environmental policy, plans, and actions that helps an organization to (1) identify and control the environmental impact of its activities, products, or services, (2) continuously improve its environmental performance, and (3) implement a systematic approach to setting environmental targets and understanding how these will be achieved and measured. And they likely have their audits certified by an independent third party and voluntarily report results to the EPA and the public.

But the companies that project credibility go beyond what is expected from regulators and other stakeholders. So, proactively, and publicly, commit to doing your share to solve emerging environmental and social problems such as protection of rainforests or elimination of sweatshops – and discover competitive advantage in the process. Being proactive projects leadership and sends a message to investors that risks are minimized. Regulators are less likely to impose restrictions on companies whose actions transcend minimum standards. Being proactive also allows companies to help define the standards by which they will be judged and affords the greatest opportunities to find cost-effective solutions to environmental ills while beating competitors in meeting regulations and consumer expectations. Finally, proactive companies are better prepared to withstand the scrutiny that overtly “green” companies often face. In 2005 our client, HSBC, became the first major bank and member of the FTSE 100 to address climate change by becoming carbon-neutral. Its carbon management program consisted of four key steps: (1) measuring its carbon footprint, (2) reducing energy consumption through an aggressive program of energy efficiency upgrades in corporate offices and bank branches, (3) buying renewable forms of electricity to power whatever energy it could not reduce through efficiencies, and (4) offsetting whatever carbon it could not reduce via efficiency and offsets. By shooting for carbon neutrality and by initiating an industry-leading Carbon Management Plan, HSBC gained the needed credibility to launch its Effie-award-winning “There’s No Small Change” U.S. retail marketing program in spring 2007, described in Chapter 6.

Be thorough

Green marketing practices have their environmental impacts, too. So look for opportunities to be environmentally efficient with marketing materials. Look for opportunities where the Internet or electronic media could work to reduce the use of paper. Be sure to use recycled paper from sustainably harvested trees and soy-based inks for printed marketing communications.

2 Be transparent

Provide the information consumers seek to evaluate your brands. These days, consumers crave even more information than most businesses are willing to disclose. Almost four out of five (79.6%) respondents in an April 2008 online survey used the Internet to conduct research on green initiatives and products, yet almost half (48%) of them found the availability of corporate information on green and environmentally safe products and services to be lacking – rating the information as fair or poor.7 To be perceived as credible in the eyes of the consumer, provide access to the details of products and corporate practices and actively report on progress. So the public can feel good about purchasing your products, include anecdotes about exemplary community outreach efforts – digging a well, tilling a farm, or helping out at a local school.

In the future, disclosure of brand-related environmental impacts and processes may be required by law. Get a jump on competitors and regulators – and score some points with consumers – by voluntarily disclosing as much as possible about your products. In the hotly contested green cleaning-aids industry, competitors Seventh Generation, Method, and SC Johnson now disclose the ingredients (but understandably not the exact formulas) of their products. Seventh Generation even lets consumers ask “Science Man” specific questions.

Be accessible and accountable. Report the good – and the bad – about your company. Consistency in reporting such data is critical to stakeholders’ ability to track progress and make comparisons. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a spin-off of the Boston-based Ceres, founders of the Ceres Principles of good corporate environmental conduct, in partnership with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). It is a voluntary global standard and framework for organizations to measure, benchmark, and report on economic, environmental, and social performance. More than 1,500 companies including BP, Coca-Cola, GM, IBM, Novartis, Philips, and Unilever have adopted this de facto standard for reporting. Ben & Jerry’s has gone one step further by also using a reporting standard called the Global Warming Social Footprint (GWSF), developed by the Vermont-based nonprofit Center for Sustainable Innovation, to understand if it is contributing its “proportionate share” (as measured against the performance of similar-sized companies) toward returning greenhouse gas concentrations to safer levels.

One thousand conscientious companies in 54 industries have also taken the step of joining the fast-growing ranks of B Corps (described in Chapter 3), denoting that the nonprofit B Lab has certified their companies to strict sustainable business standards, or they have benchmarked their performance to the organization’s free B Impact Rating System.8

It’s one thing to report on the good, but what about the bad? Under the new rules of green marketing, leaders communicate with “radical transparency.” One pathfinder is Patagonia, the Ventura, California-based outdoor equipment manufacturer. Its Footprint Chronicles microsite at patagonia.com lets visitors trace the environmental impacts of ten Patagonia products from design through delivery, including components and where they come from, innovations used to reduce impacts on the environment, and what the company thinks it can improve on. Patagonia encourages customer comments – a move that builds loyalty – and is not hesitant to critique itself; as the company learns more, it applies this knowledge to its broad spectrum of offerings. For example, despite its reputation for using recycled fibers, Patagonia is not afraid to reveal on its site that it still uses 36% virgin polyester to make its Capilene 3 Midweight Bottoms, carefully explaining that it is needed to achieve the desired performance and durability.9 In 2008, the Footprint Chronicles won high accolades as the People’s Voice winner in the Corporate Communications category at the Webby Awards (aka “the Oscars of the Internet”).10

Don’t hide behind bad news! SIGG, the makers of popular and eco-trendy reusable aluminum bottles, learned this lesson the hard way. Thought to be BPA-free by consumers and the media, SIGG came under fire when an open letter to customers from CEO Steve Wasik in August 2009 disclosed that bottles produced prior to August 2008 contained trace amounts of BPA in the bottle’s inner epoxy liner – and that the company had known about it since 2006. Although SIGG was quick to use public outreach to address consumer and retailer concerns, the damage was done. Customer trust was compromised: articles and blog posts quickly sprang up entitled “How SIGG Lost My Trust” and “Et Tu, SIGG?” written by SIGG customers who felt betrayed by the company’s lack of transparency. Competitor brands such as CamelBak and Klean Kanteen were quick to capitalize on the situation by reassuring shoppers that their products were BPA-free.11

3 Don’t mislead

Consumers may claim to know what commonly used terms such as “recyclable” and “biodegradable” mean but they can be easily mistaken, – creating risk for unsuspecting sustainable marketers. For example, products or packaging made from recycled content can be crafted from 10% recycled content or 100% recycled content. Counterintuitively, 100% recycled content is not necessarily environmentally superior to 10% if, for example, the recycled content must be shipped from far away. A package made from cornstarch may be compostable in theory, but may not break down in backyard composters; industrial composting facilities where such packages do decompose are currently limited to only about 110 communities in the United States and even these facilities may not be convenient (e.g., the closest one to San Francisco is 25 minutes away in the city of Richmond).

What about terms such as “carbon footprint,” “carbon neutral,” and “sustainable” which have recently come into the picture? Does a carbon footprint encompass only the emissions of a manufacturer in making a specific product or all of the organizations in the manufacturer’s supply chain for that same product? Opinions abound about the best way to trace claims related to “carbon offsets” and Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs). For example, advertisers sometimes sell products for which the greenhouse gas emitted during their production and/or use is offset by funding projects such as wind farms, tree planting, or methane capture facilities that may have happened already. Advertisers also may promise that a product was produced with RECs – tradable commodities representing proof that a certain amount of electricity used in production was generated from an eligible renewal energy source, again not under their domain, so the sources may not be verifiable.

Inconsistent guidelines are further complicating the carbon-offset debate. There are currently four proposed U.S. regional greenhouse gas cap-and-trade programs, nearly 30 mandatory state regional energy portfolio standards, and voluntary REC and carbon-offset markets – all with varying, and sometimes conflicting, requirements. The FTC believes use of the term “carbon offsets” in advertising can be inherently misleading if the ad does not specify the particular manner in which reductions in carbon emissions have been obtained.12

Two things are clear in this debate: adopting specific standards for disclosure will indeed be tricky, and setting standards for what is a “carbon offset” and a REC will most likely take years. Since not all carbon-offset partners are legitimate, advertisers are advised to properly vet partners prior to communicating their participation. Examples of some of the most respected include NativeEnergy and TerraPass. More detail about carbon footprint labeling is included below.

Carbon labeling issues aside, the best advice for green marketers looking to stay out of trouble is to simply follow the FTC (or other appropriate government guidelines) as best you can and, if possible, to consult with lawyers who specifically address green claims. Broad guidance based on extracts from the current FTC guides can be summarized as follows:

Be specific and prominent

Marketers are liable for what consumers may incorrectly interpret as well as what they correctly take away. Prevent unintended deception with the use of simple, crystal-clear language. For example, be sure to distinguish between the packaging of a product and the product itself, like the label on the Wheaties box on your breakfast table. Emblazoned on the lid is the familiar “chasing arrows” Möbius loop symbol with the descriptive claim, “Carton made from 100 percent recycled paperboard. Minimum 35 percent post-consumer content.” This claim is specific and, because it qualifies the exact amount of recycled materials, it prevents consumers from thinking the box is made of 100% materials collected at curbside, or is fully recyclable. Precision can pay off in credibility with consumers. For example, according to the 2008 Green Gap Survey conducted by Cone LLC and the Boston College Center for Corporate Citizenship, 36% of respondents found the message “environmentally friendly” credible when describing a paper product, but 60% found the message “made with 80% post-consumer recycled paper” credible.13

Don’t play games with type size or proximity of the claim to its qualifiers. A Lexus ad in the UK made a headline claim of “High Performance. Low Emissions. No Guilt.” The UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) deemed this to be misleading since the text of the ad clarifying the claim was not prominent enough. Plus, the claim “No Guilt” implied the car caused little or no harm to the environment.14

Provide complete information

Consider a product’s entire life-cycle when making claims about one particular characteristic or part of the item. A washing machine advertised as “green” because of its low energy and water consumption may not have been manufactured or distributed in a green way. Advertising the washer specifically as “energy-efficient” or “water-efficient” with substantiation from, or a comparison to, existing benchmarks could help to avoid misleading customers.

In the UK, an ad for Renault unfairly compared the CO2 emissions of a brand sold in the UK compared to one in France, with its significantly lower emissions levels due to a high percentage of nuclear in the energy mix. The ad was criticized by the ASA for misleading consumers. Accordingly, when comparing your own product’s sustainability benefits to those of a competitor or a previous model, provide enough information so that consumers can stack them up fairly. Make sure the basis for comparison is sufficiently clear and is substantiated by scientific test results. A claim such as “This water bottle is 30% lighter than our previous package” is preferable to the more ambiguous “This water bottle is 30% lighter.”

Do not overstate

Avoid vague, trivial, or irrelevant claims that can create a false impression of a product’s or package’s environmental soundness. The Colorado-based BIOTA brand of spring water claimed to be the first company to use a biodegradable water bottle made from corn-based bioplastic. That may be true in theory, but the average consumer does not know that decomposition can take at least 75 days and only when exposed to the continuous heat and humidity found in municipal composting facilities – conditions that do not exist in backyard composters and certainly not in landfills.15 So the company now touts itself as being “the world’s first bottled water/beverage packaged in a commercially compostable plastic bottle.”16

In August 2009, the FTC sued four manufacturers of bamboo textiles, claiming they mislabeled their products as “natural,” “biodegradable,” and “antimicrobial.” The product, akin to rayon, is not natural and uses toxic chemicals to manufacture. In addition, the biodegradable and antibacterial properties do not make it past the manufacturing process. The companies squeaked by without a penalty but will need to label their fabrics as “viscose” or “rayon” and do away with claims of biodegradability and antimicrobial.17 In a case very similar to the Hefty photodegradable trash bag debacle of 1990 the FTC also charged Kmart, Tender Corp, and Dyna-E International, for falsely claiming that their paper plates, wipes, and dry towels were “biodegradable” when most of these products simply wind up in landfills where they will not degrade.18

Broad statements such as “environmentally safe,” “Earth friendly,” and “eco friendly,” if used at all, should be qualified so as to prevent consumer deception about the specific nature of the environmental benefit of the product asserted. Preferable alternatives include: “This wrapper is environmentally friendly because it was not bleached with chlorine, a process which has been shown to create harmful substances.” Always be sure to substantiate and qualify terms such as “carbon neutral,” “renewable,” “recyclable,” and “compostable.” Answer questions such as: How have the claims been determined? For how long? By whom? Where? Compared to what?

Similar rules apply for corporate advertising. Overstating the environmental benefits of one’s efforts – wrapping one’s company in a green cloak – creates skepticism and invites backlash. In November 2007, the ASA in the UK ruled that a Royal Dutch Shell ad that showed an oil refinery (with environmentally preferable practices) sprouting flowers was likely to be misleading, given the environmental impacts of even the cleanest of refineries, and ordered the ad off TV. Less than a year later, the ASA ruled against another Shell ad claiming the oil sands in Canada were a “sustainable” energy source. The Canadian oil sands projects have proven controversial, as they require more energy and water than traditional extraction and refining. The ASA ruled that the ad was misleading since the claim of “sustainable” was an ambiguous term and that Shell had not shown how it was effectively managing the oil sands projects’ carbon emissions.19 Shell was not alone. In March 2008, the ASA banned a campaign by the Cotton Council International, a group committed to increasing the export of U.S. cotton, which referred to cotton as “sustainable.” The ASA disagreed, maintaining that cotton is a pesticide- and energy-intensive crop that depletes groundwater.20

Avoid generalities or sweeping statements such as “We care about the environment” with no connection to projects you have undertaken. Quantify plans, progress, and results. For example, if you claim your company prevents pollution, explain what kind of pollution and how much. Explain the specific emissions-reduction steps taken both internally and for specific products consumers can buy. In 2005, GE launched its Ecomagination campaign which, despite GE’s history of significant environmental transgressions, met with very little backlash. Why? The company was upfront about their belief that financial and environmental performance can work together. The initiative was built on ten products representing tangible investments and promising new technologies, and was supported by a pledge by GE Corporate to reduce its own carbon footprint. Finally, ecomagination.com helps businesses and consumers learn more about GE’s commitment, specific goals, and how customers can reduce their own “footprint.”

Tell the whole story

Decide for yourself: should advertising conducted by the U.S. Council on Energy Awareness touting the clean air benefits of nuclear energy mention the radioactive waste it generates? Should the Chevrolet Division of General Motors have run ads for cars (e.g., the Chevy electric Volt) that weren’t in production yet? Does a household paper product made from partial recycled content and bleached by a chlorine-containing compound deserved to be called “Scott Naturals”? To be certain your marketing and environmental communications do not confuse or mislead the consumer, test all green messages among your audience – and in your conscience.

4 Enlist the support of third parties

As depicted in Figure 2.7 on page 34, manufacturers and retailers have lower credibility than NGOs and government when communicating on environmental matters. Fortunately, there are many ways that businesses can bolster their own credibility, among them: let stakeholders in on the steps the organization is taking, educate the public on what they can do, and, importantly, align positively with third parties that perform independent life-cycle inventories and certify claims and award eco-seals. Once having shunned relationships with industry, many nonprofit organizations now welcome associations with industry as a way to work positively toward market-based solutions. This extends their influence within society, and helps to raise money for their groups. Third-party support can take many forms. Cause-related marketing, awards, and endorsements are all possibilities. When launching the Prius, Toyota proudly touted in supplemental ads targeted at deep-green drivers the fact that the Sierra Club, the National Wildlife Federation, and the United Nations had each bestowed some type of award or endorsement on the car.

Logos, trademarks, and symbols for greener product labels and certifications seem to be everywhere: on product packaging, marketing, and advertising communications, on websites, and at trade shows. In fact, more than 400 different eco-labels or green certification systems have been found in over 207 countries. These span the gamut of industries, but are predominant in consumer products such as paper and packaging, forest products, food, cleaning products, and household appliances. Some are government-run or -sponsored, while others are run by private corporations, trade associations, or NGOs. The labels vary in the level of rigor applied to the criteria and the rules around verification; some require independent third-party certification and stakeholder review, while others allow manufacturers to self-verify. At last count, 27 countries around the globe, including China and the European Union, have active multi-attribute eco-labeling programs that require third-party certification (see Fig. 7.1).21 More certifications and labels are expected as governments, environmental groups, NGOs, trade associations, retailers, and even manufacturers create labels and advertising symbols for products that promise environmental and social benefits.

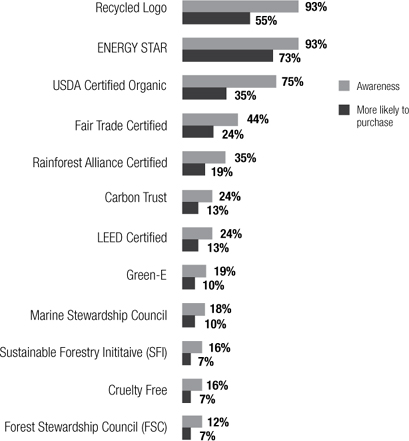

Independent seals of approval have much to recommend them, but they are not without risk. They can lend credibility to environmental messages, – 28% of consumers look to certification seals or labels on product packaging to tell whether a product is or does what it claims22 – and they can open the door to conversations with distributors and retailers. Markets that are especially receptive to eco-seals and independent claim certification include government agencies and their contractors looking to procure environmentally conscious goods, and retailers who are anxious to stock green goods but lack the ability to screen for “green” existing product lines and a constant stream of new product introductions. However, despite their apparent proliferation, eco-labels do not exist for all product categories or environmental or social attributes. For example, there is no label for mattresses or flatware. And, as seen in Figure 7.2, only a handful of eco-labels – the chasing arrows recycled logo (Möbius loop) (93%), ENERGY STAR (93%), and USDA’s Certified Organic (75%) among them – have broken through the clutter to gain awareness and, more importantly, purchase influence.

Figure 7.1 Worldwide eco-labels

Also, labels and certifications can be expensive. Many seal programs require manufacturers to test their products via third parties, and some independent organizations, such as the GreenGuard seal for indoor air quality or the C2C (Cradle to Cradle) logo, require manufacturers to pay what can amount to hefty licensing fees. What’s more, international governments will often require that a product be tested in one of their own country’s labs, creating redundancy and exorbitant extra costs for multinational marketers.

What type of criteria should be used in selecting an eco-label? It varies. Some eco-labels focus on a single product attribute (e.g., recycled content), which keeps things simple, but can potentially mislead consumers into thinking the product is greener overall. Other labels look at several characteristics of a product, or even a product’s entire life-cycle; such multi-attribute certifications may raise questions about the credibility of a single-attribute certified product while also preventing easy comparisons.

Figure 7.2 Which eco-labels work best?

% U.S. adults

Source: © Natural Marketing Institute (NMI), 2009 LOHAS Consumer Trends Database®

All Rights Reserved

Be prepared for dueling logos that fight for your consumer’s attention and your pocketbook. In the forest products industry, for instance, the FSC label denoting sustainable wood harvesting, the product of a consortium of environmental advocates, progressive timber companies, and groups that support indigenous and workers’ rights interests, competes with SFI-certified, the product of a not-for-profit spin-off of the American Forest and Paper Association and Canada’s Forest Products Association with standards that are perceived as less strenuous.23

Are there too many eco-labels? Which ones are better at helping consumers decide if a product is really “greener” than another? Should more than one label exist in a product category? Should eco-labels be single- or multi-attribute? These are all questions that are on green marketers’ minds, but may not be fully addressed even when the FTC releases their anticipated Green Guide updates. For businesses that can navigate the thicket of such challenges, enlisting a third party to attest to a product’s green bona fides provides a powerful indicator of business integrity.

Finally, for businesses for whom third-party certification does not work, the opportunity exists to create one’s own eco-label, or “self-declaration.” Independent claims and standards setting and verification exists as another alternative. Consider the following as you choose the certifications that will provide the most value to your own sustainable branding efforts:

Single-attribute labels

These labels focus on a single environmental issue, e.g., energy efficiency or sustainable wood harvesting. Before certification, an independent third-party auditor provides validation that the product meets a publicly available standard. As suggested by Figure 7.2, there are many single-attribute seals available. Many of these are sponsored by industry associations looking to defend or capture new markets, or by environmental groups or other NGOs that want to protect a natural resource or further a cause.

Two single-attribute labels with a global presence include the FSC label (used for this book) and Fair Trade Certified. The FSC label ensures the sustainable harvesting of wood and paper sources. The Fair Trade Certified label, a service of Fairtrade Labelling Organizations, a global not-for-profit group, works with local bodies such as TransFair USA to guarantee strict economic, social, and environmental criteria were met in the production and trade of a range of mostly agricultural products including coffee, tea, chocolate, herbs, fresh fruit, flowers, sugar, rice, and vanilla.

Multi-attribute labels

As their name suggests, multi-attribute labels examine two or more environmental impacts through the entire product life-cycle. Wal-Mart’s Sustainability Consortium promises to eventually deliver multi-attribute guidance in the form of a Sustainable Product Index, and several multi-attribute labels exist, primarily for specific categories such as EPEAT in electronics, and Global Organic Textile Standards, among them. Others address specific areas of concern: for instance, the Carbon Trust’s Carbon Reduction label, and the C2C label with its emphasis on material chemistry.

Figure 7.3 FSC and Fair Trade labels

Reprinted with permission from the Forest Stewardship Council and TransFair

One of the oldest and most credible multi-attribute labels in the U.S. is the Washington DC-based Green Seal (Greenseal.org), founded in 1989 by a coalition of environmentalists and other interested parties. They provide a seal of approval for products that meet specific criteria within categories where they have created standards. Companies pay a fee to have their products evaluated and annually monitored. Products that meet or exceed the standards are authorized to display the Green Seal certification mark on the product and promotional material. All products or services in a category are eligible to apply for the Green Seal. The group has finalized standards spanning a wide range of commercial and consumer products and services including cleaners and cleaning services, floor-care products, food-service packaging, lodging properties, paints and coatings, papers and newsprints, and windows and doors. Wausau Paper, Anderson Windows, Clorox, Kim-berly Clark, Hilton, and Service Master Cleaning franchises are just a few of the organizations whose products now bear the Green Seal certification mark – a blue globe with a snappy green check.

A de facto multi-attribute label, the Carbon Reduction label ensures that a product’s carbon footprint has been measured and is being reduced. The intention is that in a low-carbon economy, global climate-change-related information will ultimately become as important and visible on product labels as price and nutritional content. Introduced in 2007 by the Carbon Trust, a UK-based not-for-profit company, the label has already been adopted by more than 65 leading brands and can be found on over 3,500 individual products with annual sales worth £2.9 billion (around $4.4 billion in mid-2010).

Figure 7.4 Green Seal certification mark

Reprinted with permission from Green Seal

In April 2008, UK-based retailer Tesco commenced a test of the label on its own brand of orange juice, potatoes, energy-efficient light bulbs, and laundry detergent. Working with the Carbon Trust, Tesco seeks to accurately measure the amount of CO2 equivalent put into the atmosphere by each product’s raw materials, production, manufacture, distribution, use and eventual disposal. The label features a carbon footprint logo. Brands can also choose to indicate the amount of life-cycle-based CO2 and other greenhouse gases on its labels.

The Carbon Reduction label is expanding its global presence. Since 2007, Tesco has opened 125 Fresh and Easy stores in Southern California, Las Vegas, and Phoenix, so it is possible their carbon-labeled products may be making an appearance soon in the U.S. Working with Planet Ark; products bearing the Carbon Reduction Label were introduced into Australia in 2010.24

Figure 7.5 The Carbon Reduction label

Reprinted with permission from the Carbon Trust

Unlike some countries, including Canada, Japan, and Korea, the U.S. government has opted for voluntary single-attribute, rather than multi-attribute labels. (The private sector and not-for-profit groups hold sway in the area of multi-attribute eco-labeling.) Outside of those associated with independent testing, the government-backed labels don’t require any fees.

The most visible voluntary labeling program is ENERGY STAR (whom we at J. Ottman Consulting were proud to advise over many years). Launched in 1992, this joint program of the EPA and the U.S. Department of Energy identifies and promotes energy efficiency in more than 60 product categories including major appliances, lighting, and electronics used within homes and offices, and commercial buildings and homes. Nearly 3,000 product manufacturers now feature the ENERGY STAR label on their products. According to the Natural Marketing Institute, by 2009, 93% of the American public claimed to recognize the ENERGY STAR label, and 73% said it influenced their purchase (see Fig. 7.1).

Other EPA labels include WaterSense, to identify water-efficient toilets, faucets, showerheads, and other products and practices; Design for Environment (DfE), to acknowledge safer chemical formulations in cleaning products; and SmartWay, for fuel-efficient and low-emission passenger cars and light trucks, as well as heavy-duty tractors and trailers and other forms of transportation used in distribution and delivery operations.

Figure 7.6 Voluntary labels of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Reprinted with permission from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Labels or standards signifying that food and non-food products are organically grown exist throughout the globe, for example, in Europe (EU 834/2007), Japan (Japan Agricultural Standards), and Canada (Canada Organic Regime) and in the U.S. (USDA National Organic Program). Launched in 2002, the USDA Organic label now appears on a wide range of over 25,000 products from 10,000 companies including food, T-shirts, and shampoo. Stonyfield Farm, Earthbound Farm, and Horizon Organic are just a few of the popular consumer brands that bear the USDA organic seal on packages, advertisements, and other marketing communications, signifying that their products do not contain or were not processed with synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, radiation, antibiotics, hormones, or GMOs (genetically modified organisms); and they monitor other long-term processes such as soil management and animal conditions.25

Reprinted with permission from the USDA

Since 2002, the USDA has been running the BioPreferred program encouraging federal procurement officials to give preferential treatment to a list of 5,000 products in 50 product categories, and growing. Sensing mainstream consumer demand for biobased products – defined by the USDA as non-edible consumer and commercial products that are based on agricultural, marine, or forestry-based raw materials – Congress has authorized the USDA to ready a new label to help consumers identify biobased products. Expected to be launched in 2011, the new label (with which we at J. Ottman Consulting are pleased to be assisting), will appear on products and packaging ranging from compostable gardening bags made from cornstarch, to lip balms made from soybeans, even towels and bed sheets made with eucalyptus fiber.

Self-certification programs

Issued by manufacturers to denote their own environmental and social achievements, self-certification programs do not carry endorsements or the credibility of an impartial third party. However, they do provide distinct advantages in controlling costs and providing flexibility in the types and amounts of information that is provided to consumers. Some self-certification systems showcase government or third-party labeling.

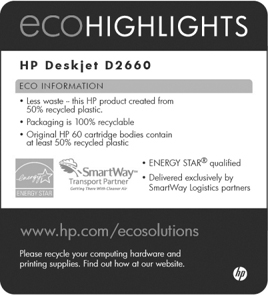

Several large companies have attempted to put forth their own self-certifications; examples include: SC Johnson (GreenList), NEC (Eco Products), Sony Ericsson (GreenHeart), GE (Ecomagination), Timberland’s Green Index, to be discussed in Chapter 9, and Hewlett-Packard (HP). Building from a history of environmental focus, HP’s Eco Highlights label, introduced in 2008, spotlights key environmental attributes and certifications on the packages of select HP products. The easy-to-read rectangular label (see Fig. 7.8), which now appears on more than 160 HP products, allows consumers who purchase selected printing, computing, and server products to learn more about features such as power consumption compared to previous models, ENERGY STAR compliance, and percentage of recycled material used in the product. It also includes specifics on the recyclability of the packaging and the product, and updates on HP’s overall recycling goals.26

Figure 7.8 HP Eco Highlights label

Reprinted with permission from HP

Independent claim verification

Independent for-profit organizations, including Scientific Certification Systems of Oakland, California and UL Environment of Northbrook, Illinois, will, for a fee, verify specific claims and develop standards in industries where none exists. They will also certify products against standards developed by other organizations. For example, they will certify commercial furniture to the new BIFMA (Business and Institutional Furniture Manufacturers Association) e3 multi-attribute, life-cycle-based standard (levelcertified.org) which was developed in line with the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards development protocols.

Environmental product declaration

ISO standards describe three types of eco-label, two of which are described above: Type I: Environmental Labels, Type II: Environmental Claims and Self Declarations, and Type III: Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs). More often used in Europe and Asia than the U.S., EPDs provide detailed explanations of the full life-cycle impacts of a given product. An excellent example is the EPD issued per ISO 14025 by Steelcase for its Think Chair, designed to fit the needs of consumers around the world. Displayed at the company’s website, Steelcase.com, the EPD shares the results of three life-cycle assessments (needed to accurately assess impacts in North America, Europe, and Asia), and describes the various certifications it has received from different countries around the globe.

Considering an eco-seal endorsement or independent claim certification for your brand? Maximize its potential value and avoid backlash by sticking to these four rules of thumb:

Choose wisely

Ensure that the organization behind the seal and its methodologies are credible. Look in particular to see that their standards have been developed in accordance with such standards-writing organizations as ISO and local bodies such as the American National Standards Institute or the British Standards Institute. Labels should be consistent with expected amendments to the FTC Green Guides as well as other appropriate national environmental guidelines.

Be relevant

With so many available, it is possible that your brand may qualify for more than one eco-label, and for more than one product attribute, e.g., ingredients, packaging, manufacturing, etc. Therefore, aim to certify those attributes that are most relevant to your brand. Also, integrate your eco-labels into existing brand platforms. GE’s Ecomagination (and more recent Healthy Imagination) designations extend from the company’s longstanding “Imagination at Work” brand platform.

Educate

Let consumers know about the specific criteria upon which your eco-seal is based. With single-attribute labels, take care to communicate that only the specific product attribute is being certified and do not imply that the entire product is “greener” as a result. For credibility’s sake, if appropriate, communicate attempts to extend the greening process to other product attributes. Products bearing self-declarations are advised to identify their label as having been issued by their own organization to avoid misleading consumers otherwise. For added credibility, products with self-declarations can consider third-party certification. Share additional details on a corporate website.

Promote your eco-label

Considering that many eco-labels are not widely recognized, help to create demand for your eco-label via marketing communications consistent with your seal’s own guidelines. The ENERGY STAR label enjoys strong awareness thanks largely to the promotional efforts of the many manufacturers whose products bear the label, coupled with pro bono advertising. Be sure to look for opportunities to distinguish your commitment to your selected eco-label from competitors using the same label. Earning and promoting ENERGY STAR “Partner of the Year” status is one good route.

5 Promote responsible consumption

Are Frito’s SunChips’s bags truly “compostable” if consumers drop them in the trash rather than a composting bin? Is an ENERGY STAR-rated light bulb really green if it remains on after everyone leaves the room? It is one thing to design a product (and its system) to be greener, but impacts throughout the total product life-cycle cannot be minimized unless people use (and dispose) of it more responsibly. “Responsible consumption” – what I consider to be the high road of green marketing and product development – is about conserving resources associated with using products, including encouraging consumers to use only what is needed, and consciously reduce waste. Sustainability leaders are striving for the ideal goals of zero waste and zero energy, but we will never get to zero until consumers learn to responsibly consume and properly dispose of the products they buy.

As discussed in Chapter 4, consumer usage can represent a significant portion of a product’s total environmental impacts, especially when it comes to those that consume resources such as energy or water. Products can be designed to make it easier for consumers to minimize resource use, like a duplex printing feature on a printer, or a dual-flush toilet. Real-time information, like Toyota’s dashboard and the new crop of energy meters and monitoring services help, too.

Representing what is now an unwritten rule of green marketing – but one that will undoubtedly be writ large in the not-too-distant future – enlisting consumer support for responsible consumption is a sure-fire way to build credibility and reduce risk. Consumers intuitively understand that it is not possible to spend our way out of the environmental crisis. At the micro level, simply switching one supermarket cartful of “brown” products with “green” ones will not cure environmental ills. Creating a sustainable society requires, among other things, that every one of us use only what we need and that we help to recapture resources for successive uses through recycling and composting. When markets fail to address environmental ills, governments are sure to intervene. (Witness mandated shifts to energy-, fuel- and water-efficient appliances, light bulbs, and cars. Will cold-water laundry detergents, organic cotton, and leather-free shoes be next?) Another issue industry needs to be mindful of “the rebound effect” – whereby consumers will buy or use more of a product if it costs less to use due to enhanced efficiency. The classic case is fuel-efficient cars that are driven more miles than less-efficient vehicles.

As we learned when advising HSBC, a key to the credibility of their There’s No Small Change campaign was empowering individuals and businesses to reduce their carbon footprint, in line with the bank’s own efforts. In other words, we weren’t asking HSBC’s customers to do anything the bank hadn’t already done itself. Cognizant of the risk associated with promoting a compostable bag that might only get thrown away, Frito-Lay emblazons a “compostable” message on its SunChips bags and supports additional education through a television campaign and website. Below are examples of ways that businesses are winning their stakeholders’ respect by communicating the need to consume responsibly especially in the area of energy use.

HP earned the #1 spot on Newsweek’s list of the top green companies of 2009 by pledging to reduce product emissions and energy usage 40% from 2005 levels by 2011. Realizing it needs to partner with consumers to reach that goal, the company has launched its Power to Change campaign, encouraging users to turn off their computers and printers when they do not need them. Users can download software that reminds them to turn off their computers at night and tracks actions to calculate energy and carbon impact.

Levi Strauss and Co. has teamed up with Goodwill to educate consumers on how to lower the life-cycle impacts of blue jeans. The company’s A Care Tag For The Planet campaign uses online and in-store messaging and a new care tag on jeans to encourage owners to wash in cold water, line dry when possible and, at the end of their useful life, to donate their jeans to Goodwill thrift stores. The company estimates that such steps taken by responsible consumers can reduce the life-cycle climate-change impacts by 50%. Relat-edly, in Europe, Procter & Gamble’s Ariel runs a Turn to 30 (degrees centigrade) campaign to encourage consumers to wash at lower temperatures, and spurred by the threat of regulation, the laundry detergent industry as a whole has united to promote responsible washing. And an industry-wide Washright campaign (washright.com), launched in 1998 by the Brussels-based International Association for Soaps, Detergents and Maintenance Products (AISE), reached 70% of European households with tips on how to wash laundry in environmentally preferable ways.27

A final example: the Sacramento Municipal Utility District now knows that peer pressure is an excellent strategy for promoting responsible consumption – and may be even more motivating than saving money. In a test that began in April 2008, 35,000 randomly selected customers were told via “happy” or “sad” faces printed on their monthly utility bills how their energy use compared with their neighbors’ and with that of the most efficient energy users in the district. Customers who received the information cut their electricity use by 2% compared to flat usage by counterparts who did not receive messages. The utility expanded the program to 50,000 households in August 2009.28

Operating by the new rules of green marketing requires new strategies for engagement with the vast panoply of stakeholders who are motivated to help businesses green their products, develop effective communications, and engage consumers in exciting new ways – the subject of the next chapter.

As we go to press. . . The FTC issued proposed revisions for their Green Guides, which were last revised in 1996. The proposed Guides can be located at ftc.gov/opa/2010/10/greenguide.shtm. After the requisite rule-making process including comment period, the revised guides will be finalized, likely in the spring of 2011. The content of the proposed revisions are consistent with much of the guidance in this book. Please visit the author’s website, www.greenmarketing.com, for continuing updates and her analysis.

The New Rules Checklist |

Ask the following questions to help ensure credibility for your green marketing claims and communications.

![]() Are we walking our talk? Does our CEO openly support sustainability? Do our stakeholders know it?

Are we walking our talk? Does our CEO openly support sustainability? Do our stakeholders know it?

![]() Are our green marketing claims consistent with our corporate actions? (i.e., are we making claims that are true?)

Are our green marketing claims consistent with our corporate actions? (i.e., are we making claims that are true?)

![]() Are we following official guidelines for environmental marketing claims? Are we keeping up with the dialogue on the use of newer environmental marketing terms? Does our state and/or our company’s legal department have its own guidelines for the use of environmental marketing claims?

Are we following official guidelines for environmental marketing claims? Are we keeping up with the dialogue on the use of newer environmental marketing terms? Does our state and/or our company’s legal department have its own guidelines for the use of environmental marketing claims?

![]() Have we thoroughly considered all that can go wrong so as to minimize the chances of backlash from greenwash and enjoy the full benefits of positive publicity? Do we have a process for monitoring our online reputation?

Have we thoroughly considered all that can go wrong so as to minimize the chances of backlash from greenwash and enjoy the full benefits of positive publicity? Do we have a process for monitoring our online reputation?

![]() Are our brand-related sustainability claims meaningful, specific, complete, and without exaggeration? Have we tested their believability among consumers?

Are our brand-related sustainability claims meaningful, specific, complete, and without exaggeration? Have we tested their believability among consumers?

![]() Are we being transparent about the pollution our products represent as well as their environmental benefits?

Are we being transparent about the pollution our products represent as well as their environmental benefits?

![]() Are we being environmentally efficient with our marketing materials? Have we identified where the Internet or electronic media could work to reduce our use of paper? Are we using recycled and/or sustainably harvested paper and vegetable-based inks for our marketing communications?

Are we being environmentally efficient with our marketing materials? Have we identified where the Internet or electronic media could work to reduce our use of paper? Are we using recycled and/or sustainably harvested paper and vegetable-based inks for our marketing communications?

![]() Are we taking advantage of third parties to underscore credibility? Are we considering our own self-declaration or the use of third-party verifiers?

Are we taking advantage of third parties to underscore credibility? Are we considering our own self-declaration or the use of third-party verifiers?

![]() Do consumers know how to use and dispose of our products responsibly? In what ways might we make it easier for consumers to practice responsible consumption of our products and packages?

Do consumers know how to use and dispose of our products responsibly? In what ways might we make it easier for consumers to practice responsible consumption of our products and packages?