Barriers to Scientific Reasoning

We see only what we know.

—Goethe

Overview

There is often a wall separating our desire to improve our scientific reasoning skills and our ability to do so. This makes the lessons of epistemology and philosophy of science all the more compelling, because they instruct us to reflect on how well we think.

For example, later in this book I will be introducing you to David Hume (1711–1776), an eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher famous for “Hume’s Problem of Induction.” Briefly, Hume states that we cannot assume that patterns we see in nature (or markets) will repeat themselves. If we see 100 white swans, we cannot assume that all swans are white—and in fact they are not, as you will find black swans in Australia.

Now, fast-forward to the late twentieth century. Rick Schaden and his father purchased the Quiznos franchise with eighteen outlets in 1991, and it became a roaring success. The number of outlets grew to nearly 5,000 before the recent recession. Schaden and his business partners felt they would be seeing white swans for a long time in their leveraged buyout (LBO) of Quiznos in 2006. A business article at the time “noted that the financing package to back the LBO came to market last week and says that the $925-million deal is expected to be well received by investors because it is ‘fresh paper among the refinancings and repricings that have been filling the market recently.’”1 On July 21, 2011, a Wall Street Journal’s headline announced: “LBO, Recession Singe Quiznos: Sub Chain Loses 30% of Its Outlets; the $4 ‘Torpedo’ Bested by the $5 Foot-long.”

Commenting on the mindset at the time of the LBO, Darren Tristano, executive vice president at restaurant consulting firm Technomic Inc., said that [italic added] “Before the recession, most of us believed the restaurant industry could continue to grow by leaps and bounds, so when you combine the recession with having a lot of debt, it creates two enormous barriers to success.”2 Oh, oh, here comes a black swan. (I could be accused of 20/20 hindsight here. After all, we all make bets on the sun rising tomorrow morning. But if you read The Wall Street Journal article, I believe you will agree that Schaden and his business partners simply did not think through the logical consequences of what they were doing. For example, they did not have a backup plan to mitigate the effects of a downturn in their industry.)

This chapter offers a discussion of selected topics, some taken from the fields of psychology and neuroscience, that helps us understand some of the barriers to effective thinking. Reflective thought, combined with the tools of scientific reasoning, can help us tear down these barriers. I review findings from (1) the new field of ameliorative psychology whose primary purpose is to make normative recommendations on how to think more clearly; (2) neuroscience’s investigations into how emotions make us feel that our judgments are correct; and (3) psychology’s research into how we are prone to see patterns in data that do not exist. Additionally, I discuss constraints imposed on decision makers by the very organizations in which they are employed.

Some barriers are not easily overcome, but unless we make ourselves aware of them, they will always lie between us and our goal to think more critically. There certainly are more barriers frustrating our ability to apply scientific reasoning to the field of marketing than those I discuss in this chapter. Consequently, at the end of this book, I provide a list of other reference materials you might want to consider in exploring this subject in greater detail.

Ameliorative Psychology

When we make an error in reasoning that results in a failed outcome, we can often reflect on our mistake and improve our critical thinking skills. Perhaps our worst enemies are actually the good decisions we make, because we are totally clueless that they could have been better. This is the thesis that Michael Bishop, associate professor of philosophy at Northern Illinois University, and J.D. Trout, professor of philosophy and adjunct professor at the Parmly Hearing Institute at Loyola University Chicago, put forth in the field of ameliorative psychology, which they define as giving “positive advice about how we can reason better.”3

A major and persuasive point they make about obtaining feedback on the quality of our reasoning powers is that no matter how much feedback we receive, it is incomplete. For example, consider the following:

• You have a particular way of approaching and thinking about solving a certain marketing problem. Assume this decision relates to a marketing program designed to increase demand for one of your products.

◦ You talk to the managers of the departments affected by your decision and receive their advice on actions to take (e.g., change advertising, increase advertising, and offer price rebates).

◦ You analyze relevant historical data; What has worked or not worked in the past?

◦ You distill the factors that you feel will most influence the outcome’s success.

◦ You develop potential strategies and tactics.

◦ Then you make your decision.

• Assume your boss grades the outcome success or failure on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 denotes a poor outcome and a 10 denotes a successful outcome.

• For this decision, the outcome is a relative success. Your supervisor rates your performance a 9.

Despite your success, there is an important piece of missing information that bars you from critically examining the true quality of your critical thinking skills. By definition, you do not know the outcomes of different decisions using alternative thinking strategies. That is impossible. We cannot turn back time. In other words, it is impossible to put decision makers in different control groups to examine how different thinking strategies might have affected a decision and the associated outcome’s success. This situation serves as a wall that is impossible to scale, look over, and see if a different thinking strategy would have produced a better outcome. Nevertheless, alternative ways you could have thought about the problem (a topic we discuss in more detail in later chapters) might have been engaging in a formal exercise questioning and analyzing the premises and internal logic of the arguments supporting the decision.

Even in situations in which we employ a poor thinking strategy and receive accurate feedback on our performance (e.g., the promotion did not increase sales), the way we internalize that information may diminish our ability to act on this feedback successfully. After all, we are only human. Consider the following study that examines how gamblers recall their wins and losses:

They spent more time discussing their losses than their wins. Furthermore, the kind of comments made about wins and losses were quite different. The bettors tended to make ‘undoing’ comments about their losses—comments to the effect that the outcome would have been different if not for some anomalous or ‘fluke’ element…. In contrast, they tended to make ‘bolstering’ comments about their wins—comments indicating that the outcome either should have been as it was, or should have been even more extreme in the same direction…. By carefully scrutinizing and explaining away their losses, while accepting their successes at face value, gamblers do indeed rewrite their personal histories of success and failure. Losses are often counted, not as losses, but as ‘near wins.’4

From the above discussion, we can conclude the following: (1) We can only get incomplete feedback on the success of our scientific reasoning skills regardless of their apparent success; and (2) our human nature can affect our objectivity in reflecting on how well we think.

On Being Certain

If I tell you that 3 + 3 = 6, you will not only agree, but you will experience a feeling of certainty that you are correct in your agreement. When we make a decision that we believe is correct, or we state a proposition that we believe is true, we experience what neurologist Robert A. Burton, M.D., characterizes as a feeling of knowing.5 When we think we are right, we also feel that we are right; and it is that feeling of knowing that sometimes causes us to hold on to a belief which, in the face of sometimes incontrovertible evidence, is wrong. Just think of the times when your judgment has been challenged and you held your ground. Because you felt you were right.

The hypothesis that Burton submits to explain this phenomenon is that the feeling of knowing is an evolutionary trait required for survival. When our distant ancestors were confronted with a life-threatening situation—a hungry lion or spear-welding intruder—they had to make a decision quickly either to hold their ground (not likely in the lion case) or to flee. And they had to be committed to their decision—no lollygagging around, or debating the situation with one’s self or a nearby tribal member. This commitment was both cognitive—appraising the situation and emotional—feeling one was making the right decision. Overtime, these decisions were validated by life or death and, through natural selection, became part of our DNA.

Perhaps one of the most famous studies that illustrate the feeling of knowing is the Challenger Study conducted by Neisser and Harsh in 1992. In recounting the memory of first learning about the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger catastrophe, a student whom we will call RT wrote the following 24 hours after the disaster:

I was in my religion class and some people walked in and started talking about [it]. I didn’t know any details except that it had exploded and the schoolteacher’s students had all been watching, which I thought was so sad. Then after class I went to my room and watched the TV program talking about it and I got all the details from that.6

Two-and-a-half years later, RT recalled this experience as follows:

When I first heard about the explosion I was sitting in my freshman dorm room with my roommate and we were watching TV. It came on a news flash and we were both totally shocked. I was really upset and I went upstairs to talk to a friend of mine and then I called my parents.7

The point I want to make here is not that we all suffer from memory problems. Rather, it is the emotional certainty that the students in this experiment expressed about their later recollections that, in varying degrees, did not match their initial recollections of the disaster 24 hours after it occurred. As the study authors report:8

They are so sure of themselves that it seems downright discourteous to dispute their claims, and (except for a few isolated cases) we have had little basis [outside of the students’ recorded memories 24 hours after the disaster] on which to do so.9

It is this emotional certainty of our beliefs—this feeling of knowing—that can serve as a barrier to our critical thinking.

Pattern Bias

I want to introduce you to an infamous psychology experiment conducted by Loren and Jean Chapman at the University of Wisconsin in 1969, using the Rorschach inkblot test.10 It focused on what psychologists call illusory correlation. (As an aside, I recall being a subject in one of these Rorschach tests in 1959. The “subject” is the person looking at and interpreting the inkblots. Please do not misunderstand me. The psycho-diagnosticians who administered these tests administered them to all the psychopaths in the second grade at Overland Park Elementary School, in Overland Park, Kan. I was not singled out.)

The thesis of the Chapmans research is very much reflective of the quote leading into this chapter, “We see only what we know,” from the famous German polymath, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832). At the time, homosexuality was viewed as a mental illness and, consequently, was the topic of many psychological studies. The Chapmans did their study in this area to probe the validity of tests that psychologists were using to diagnose mental conditions. Trained psychologists—the “psycho-diagnosticians”—administered and interpreted the test. Many of these diagnostic tests were felt to be invalid. For example, the tests would indicate the existence of a mental illness when, in reality, none existed.

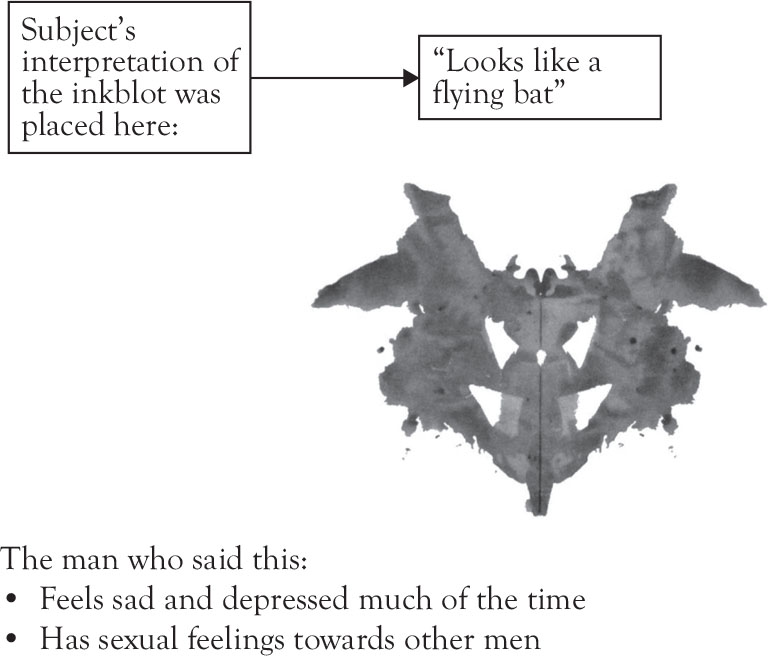

Presumably, what a subject “sees” (or admits seeing) in a Rorschach inkblot reveals latent personality characteristics. Some of the data the Chapmans collected involved having 693 undergraduate psychology students play the role of the psycho-diagnosticians, by interpreting “30 Rorschach cards on each of which was arbitrarily designated a patient’s response [what patients said they saw on the card] and his two symptoms.”11 Each student saw the same 30 cards. See Figure 4.1 for a hypothetical example of these stimuli. After the exercise, the students were asked whether they noticed any relationships in the data among the 30 cards. In their experiment, the Chapmans tested the following four symptoms:

1. He has sexual feelings toward other men.

2. He believes other people are plotting against him.

3. He feels sad and depressed much of the time.

4. He has strong feelings of inferiority.

Figure 4.1. Hypothetical example of Rorschach inkblot stimulus examined by 693 students in the Chapmans’ experiment.

In the 30 cards, there was no association among the inkblots, the patient’s response, or the patient’s symptoms. Yet, the students reported observing significant “perceived” correlations between (a) some of the inkblots that subjects said suggested aspects of the human anatomy (I’ll leave it to your imagination) and (b) homosexuality. Importantly, findings in the study corroborated other research at the time supporting the view that many experienced, practicing psychologists were also suffering from the same perceptual illusionary correlation that the student subjects exhibited. What caused this? Preconceived notions in the field of psychology at the time held that homosexuals would perceive certain suggestive inkblots as reflecting parts of the human anatomy. As the psychologist Dr. Cordelia Fine comments on the Chapmans’ research:

On the surface it seemed a plausible hypothesis. Gay men talking about bottoms: who needs Dr. Freud to work that one out? With a deceptively convincing hypothesis embedded in your skull, it’s only one short step for your brain to start seeing evidence for that hypothesis. Your poor, deluded gray matter sees what it expects to see, not what is actually there.12

You might be asking yourself why I reference such an old study dealing with a debunked psycho-diagnostic technique. First, it has become a famous article in psychology. Second, consider the following: Many of the readers of this book are practicing marketers. For a variety of reasons, we sometimes see associations in marketing phenomenon that corroborate our preconceived notions, that simply are not there, or at minimum, are ambiguous. For instance, I have had situations where clients observing the same focus group cannot agree on what respondents said most influenced their purchase decisions. When I was director of Consumer Insights for Mercury Marine, a boat engine manufacturer headquartered in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, I was in a meeting in which two experienced executives with similar backgrounds in the fishing market could not agree on the desired attributes they believed customers seek in a 60–90 hp outboard engine. How influential is the engine’s weight? These two experienced experts could not agree. We see what we know.

Causal Reasoning

If there is any gold standard in the fields of epistemology and the philosophy of science, it is the utilization of test and control groups to test hypotheses. You are likely familiar with this concept in various media accounts of pharmaceutical companies testing new drugs. The new drug is administered to the test group and either a placebo or an existing drug is given to the control group. Subjects in the two groups are supposed to be comparable on factors that potentially could bias the results, such as the severity of the disease being treated, age, gender, and race distributions. Consequently, if there is a difference in the drug’s performance between the test and control groups, this difference can be attributed to the drug and not some other factor. Science calls these controlled experiments.

By analogy, if you want to know, for instance, whether giving a price rebate or increasing advertising expenditures would have greater effect on sales and profits, you could conduct a controlled experiment. You would select test and control markets that are comparable on factors that affect the sales of your product, such as size of trade area, household personal discretionary income, and demographic make-up. In this example, you might construct an experiment with two test markets—one for the price rebate strategy and another for the advertising increase strategy—and a control market in which no changes to the marketing mix are made. Run the experiment and measure the results.

In my experience, most companies do not have the resources or time to conduct such experiments. Notable exceptions are consumer packaged goods companies such as General Mills or Proctor & Gamble. Consequently, unless your company conducts such experiments, your ability to understand the relative effects of various marketing programs on sales and profits is compromised. There are ways around this problem, such as developing “marketing mix models;” but these methods are not without their own shortcomings. The brutal fact is that, unless you are able to conduct experiments, the ability to study the cause-and-effect relationships among different marketing programs is compromised. For most companies, this is reality and a barrier to critical thinking.

No Marketing Research Budget?

Not having the ability or resources to conduct controlled experiments can be part of a much larger problem, which is simply that an organization does not sufficiently fund a marketing research budget. This position literally flies in the face of a central tenant of epistemology as it is widely received today, which is that only empirical evidence can justify beliefs as knowledge. Ameliorative psychology even has a term for people who prefer their own reasoning powers to empirical validation—epistemic exceptionalism.13

I am a realist and recognize that market conditions can put pressure on organizations from time to time to reduce or even eliminate primary marketing research expenditures, for example, when a company feels it is fighting for survival, as many have during the most recent recession. I also recognize that there are some extremely successful companies around that do not conduct formal marketing research, but learn about their markets through other avenues, such as talking to their sales force and/or channel members. There is at least one company, Apple, whose leaders do not believe in formal marketing research. Consider Steve Jobs’s comments in the following interview:

It’s not about pop culture, and it’s not about fooling people, and it’s not about convincing people that they want something they don’t. We figure out what we want. And I think we’re pretty good at having the right discipline to think through whether a lot of other people are going to want it, too. That’s what we get paid to do. So you can’t go out and ask people, you know, what’s the next big [thing.] There’s a great quote by Henry Ford, right? He said, ‘If I’d have asked my customers what they wanted, they would have told me ‘a faster horse.’14

As I said in Chapter 1, this is not a marketing research textbook. Nevertheless, marketing research done properly can be a potentially powerful tool in helping you apply scientific reasoning to your marketing problems and challenges. Absent this resource, however, the metaphorical wall that I talked about in the introduction to this chapter only gets higher and harder to scale.

But there is some hope in attempting to scale that wall if you don’t have access to marketing research, and that is to learn how to reason more scientifically. Before we begin to explore those thinking tools in some detail, however, the next chapter discusses one more barrier to our thinking clearly—worldviews.

Thinking Tip

It is darn hard to think critically. “There are things we don’t know that we don’t know,” famously quipped former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.15 Our inability to know how different outcomes may have unfolded given a different way of thinking about a problem, our feeling of knowing, and our limitations without marketing research seem to make the task of knowing what we don’t know an insurmountable undertaking. “We see only what we know,” said Goethe in his Introduction to the Proplyäen, a journal Goethe co-authored with Johann Heinrich Meyer16 and concludes the paragraph with “…perfect observation really depends on knowledge.”17

In other words, our understanding of an object or situation is based on the sum total of our experiences, beliefs, and knowledge. How do we climb this barrier? You are taking the first step simply by reading this book, which I hope will improve your ability to apply scientific reasoning to marketing. It may inspire you to broaden your reading to include psychology, sociology, marketing theory, and behavioral economics. Expose yourself to the central principles and latest thinking in these fields. In a word, read.

Chapter Takeaways

1. There are barriers to developing scientific reasoning skills that we need to recognize. Not recognizing them can frustrate our desire to think more critically.

2. While encouraging you to read the last chapter of this book that provides additional reading materials on this subject, I discussed the following selected barriers to improving your scientific reasoning skills:

a. From the field of ameliorative psychology: Perhaps our greatest enemy to understanding how we can make better decisions are the very best decisions we make, because we cannot know how a different approach and thinking strategy might have led to a different decision and associated outcome. Moreover, our human nature often programs us to rewrite our historical failures while accepting our success at face value.

b. Neuroscience research suggests that confident decisions are supported by a feeling of knowing that we are right. When we think we are right, we feel we are right. In other words, our confidence is supported by more than a rational analysis of a situation and making our best decision. This feeling of knowing, drawn in such stark relief in the Space Shuttle Challenger study, can serve as a significant barrier in developing our scientific way of thinking and acting.

c. The notion of pattern bias suggests that we sometimes see patterns in phenomenon that simply are not there. “Difference of opinion makes for horse races,” Mark Twain was famous for saying; to whom Daniel Patrick Moynihan would say, “You are entitled to your own opinion, but not your own facts.”

d. For a variety of reasons—lack of budget or management support—you simply may not be able to conduct controlled experiments or do all the marketing research you would like to test your hypotheses. Your only fall-back strategy, in these cases, is to hone your scientific reasoning skills, and use those skills to come to the best solution as possible.