The Lens that Can Distort Reality

But these rose colored glasses that I’m looking through

Show only the beauty, ‘cause they hide all the truth.

—John Conlee

Worldviews

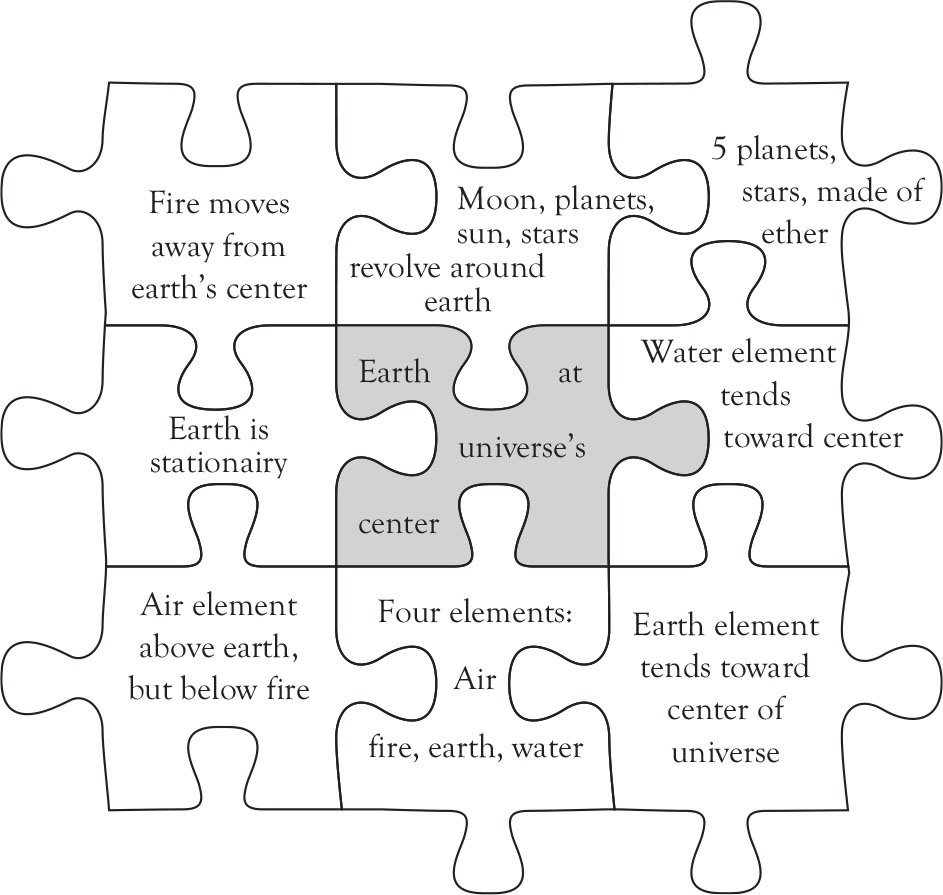

A worldview is a lens through which we view and interpret reality. We see this in everyday life. Different groups of people have different worldviews: Conservatives versus liberals, teenagers versus adults, labor versus management. More formally, a worldview “is a system of beliefs that is interconnected in something like the way the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle are interconnected. That is, a worldview is not merely a collection of separate, independent, unrelated beliefs, but is instead an intertwined, interrelated, interconnected, system of beliefs.”1 The significance of worldviews to the success of a business cannot be overstated because worldviews of senior management set the stage for how an enterprise is managed and directed. Even more critical is the extent to which worldviews are based on properly justified beliefs.

Borrowing from the history of the philosophy of science, I cover the Aristotelian worldview first because doing so will help you understand and better appreciate a critical point made later in the book about how deceiving and wrong worldviews can be. It’s a fun story and one that I believe you will enjoy. Additionally, you may be as surprised as I was to learn that, with only the unaided eye, it is impossible to disprove the core belief of the Aristotelian worldview that our planet is at the center of the universe. Indeed, it is an amazing and instructive story for marketers, and I follow it up with two applications to the field of marketing.

Aristotelian Worldview

The Aristotelian worldview is not the personal worldview of Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), the famous student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great, as much as it is the worldview of Western civilization from Aristotle’s time to around the mid-1500s. This worldview states that our universe comprises four elements—earth, water, air, and fire. Each of these elements has an essential nature, which “reflected…the way that element tends to move.”2 The material earth tended to move toward the center of the universe. Throw a rock up in the air, and its nature was to fall to Earth—actually, toward Earth’s center. Water tends to move toward Earth’s center, but this tendency is not as strong as earth’s. Air tends to move above the earth and water, but this tendency is less than fire’s, which has a tendency to move away from the earth’s center. Earth’s moon, the observable planets, and the stars are composed of “ether.” Their essential nature is to move in circles about Earth. See Figure 5.1, which gives a time elapsed photograph of the stars’ movement in the night sky.

Figure 5.1. Time elapsed photography showing stars “Revolving” around the Earth.

Disproving the Aristotelian Worldview

This may seem an ancient and ignorant worldview to us living in the twenty-first century. But the fact is, this worldview is very difficult to disprove for three reasons: (1) the apparent motion of the Sun relative to our position on Earth; (2) mathematical models from the time of Aristotle to the mid-1500s did a pretty good job of predicting the future locations of the observable planets; and (3) something called the stellar parallax.

The first reason is self-evident. Simply by making casual observations throughout the day (and night), we all notice that the Sun (and stars and planets) appear to revolve around our planet. This is especially made apparent through time lapsed photography.

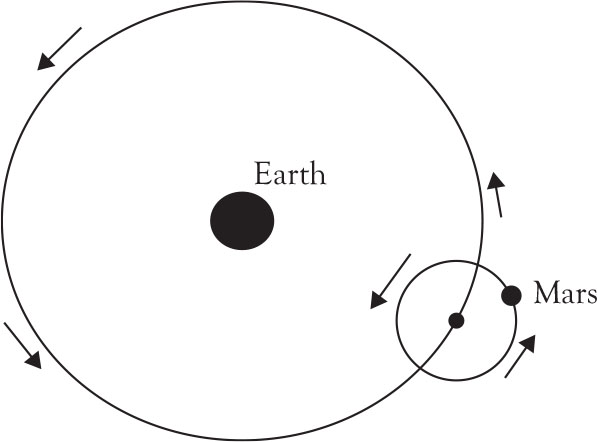

The force of the second argument is compelling because on the surface it is a believable theory. For more than 1,600 years, several astronomers—from the Greeks to the Danish nobleman Tycho Brahe (1546–1601)—developed quite intricate explanations of planetary motion with corresponding mathematical models that could reliably predict future positions of the observable planets, which at the time were Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Most notably, Claudius Ptolemy (c. 90–c.168 A.D.) was the first astronomer to develop an explanatory model of circular planetary motion, incorporating epicycles that did a fairly accurate job of predicting planetary positions (c. 150 A.D.).3 See Figure 5.2 for a graphic representation of an epicycle. In this example, Mars rotates in a circle about point (i.e., the epicycle), and this point rotates around Earth. In Ptolemy’s model, planet epicycles were needed to explain “retrograde” or “backward” motions of the planets—a planet’s apparent reversal of motion, at various times, from our view on Earth. Even at the time Copernicus published his hypothesis of the Sun-centered universe in 1543, Tyco Brahe proposed a compromise model in which the Sun and moon revolved around Earth, while the planets revolved around our Sun.4

Figure 5.2. Ptolemaic system of Mars’ motion.

The final argument supporting the Earth-centered view of the universe is something called the stellar parallax. A parallax is the seeming displacement of an observed object due to a change in the observer’s position. Perform this quick experiment and you will experience firsthand what a parallax is. Go outside. Raise your right arm so that it is horizontal to your shoulders and stick your index finger up vertically. With your right eye closed and left eye open, look beyond your index finger and notice the scene in the background. Now, close your left eye, and view with your right eye the scene behind your index finger. Objects in the background appear to move to your right. Now, consider what pattern the night stars should project to our eyes when Earth is on opposite sides of our Sun. We should see a different pattern. But we do not; and that was further astronomical evidence that the stars and planets indeed revolved around Earth. The reason the pattern of the stars we see at night does not change when Earth is on opposite sides of the Sun is that the stars are so far away from us—a conclusion that late sixteenth-century astronomers finally adopted.

The complete story of how the Aristotelian worldview gave way to the Newtonian worldview is fascinating, but beyond the scope of this book. (I will quickly tell you one important factor to feed your curiosity. With the invention of the telescope, the Aristotelian worldview could not explain the various phases of Mercury, whereas a Sun-centered view of our solar system could.) The major point that I want to make in introducing you to the Aristotelian worldview is that it is not intuitively obvious that Earth revolves around the Sun. Consequently, it may also not be intuitively obvious to recognize that some aspects of your marketing worldviews are incorrect; including what you believe might explain the behavior of the consumers you are targeting.

Thinking Tip

An epistemic virtue “is a character trait that makes you better suited to gaining the truth.”5 Applying scientific reasoning to marketing is an epistemic virtue. Additional examples of these virtues are being conscientious in how we form and shape our beliefs, critiquing the premises underlying our arguments, and how we go about empirically verifying what we believe.

There is a natural tension between investing in and developing our epistemic virtues and managing a marketing organization. Running a business is like playing a tennis match: You don’t have the luxury to ponder your next move; you have to react quickly to changing marketing conditions.

I cannot give you a recipe to follow in managing that tension effectively, other than to relate the story of Daedalus and Icarus. Daedalus built wings made of feathers, secured by string and wax, for himself and his son, Icarus, to escape the wrath of King Minos. Daedalus warned his son to “fly the middle course,” between the sea foam and the sun’s heat. Ignoring his father’s advice, the son flies too close to the sun, melting the wax off his wings, and plummeting to his death.

Try to find this middle course in dealing with the natural tension between investing in and developing your epistemic virtues and managing the daily pressures of a marketing organization.

Worldview Properties

Worldviews are systems of beliefs that resemble jigsaw puzzles and possess four characteristics: (1) the beliefs are not independent of each other, (2) the relative importance of an individual belief is directly related to how close that belief is to the center of the puzzle, (3) peripheral beliefs can be replaced without threatening the worldview, however, (4) changing a core belief at the center of the “puzzle,” will significantly alter the worldview system, and affect the peripheral beliefs.6 Refer to Figure 5.3 for a depiction of the Aristotelian worldview “puzzle.”

Figure 5.3. Aristotelian worldview.

Beliefs are not independent of each other. For example, in the Aristotelian worldview, Earth is the center of the universe and the earth and water elements naturally tend toward the universe’s center. Being at the center of the universe, Earth is stationary. The moon, planets, and stars revolve in perfect circles around stationary Earth. These beliefs are interconnected like a puzzle.

The relative importance of a given worldview belief varies inversely in proportion to its distance from the puzzle’s center. The anchor of all Aristotelian beliefs is Earth being at the center of the universe. If that belief is broken, the entire puzzle falls to pieces. In contrast, the belief that there are five planets is not critical to the worldview. More planets can be discovered and not threaten the Aristotelian core belief.

Worldviews in Marketing

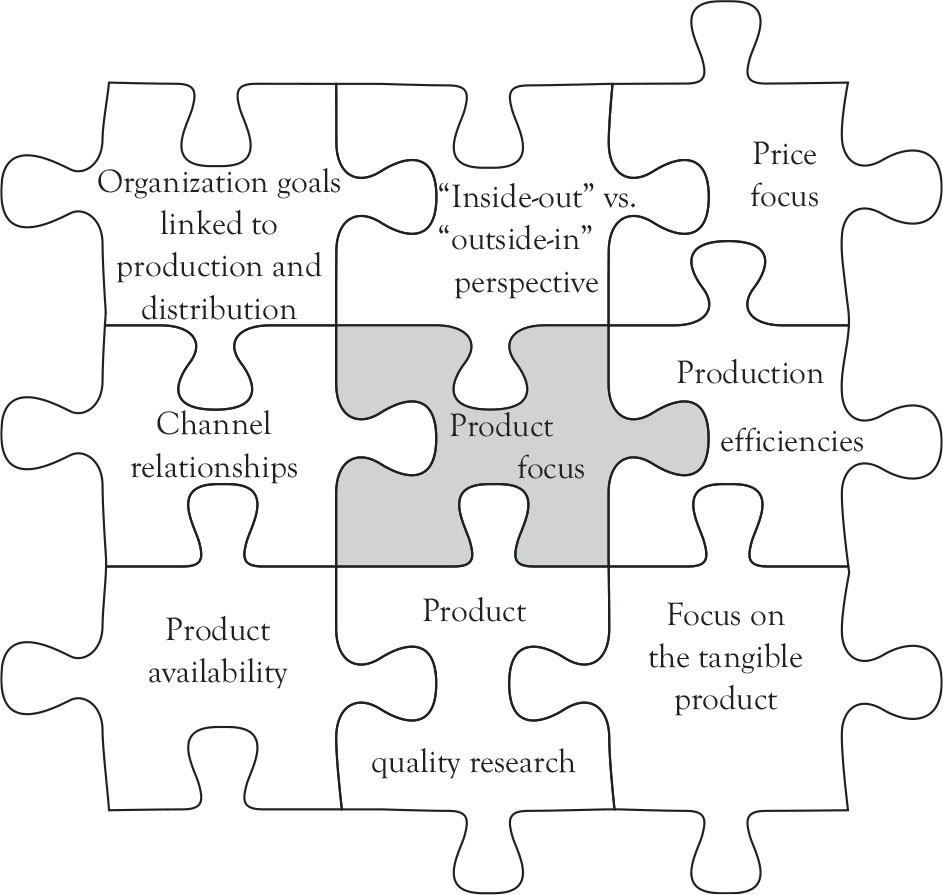

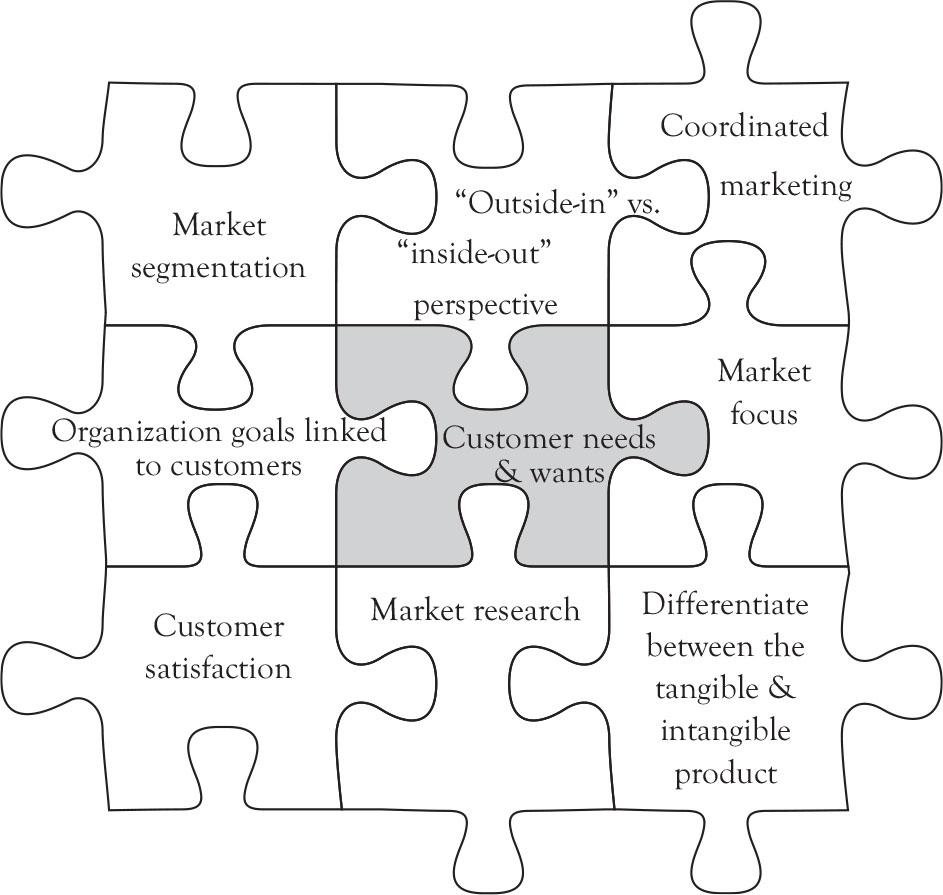

Now let’s turn to marketing. Philip Kotler, author of the most widely used graduate-level textbook in marketing management,7 raises the philosophical issue about how senior management should run an organization. “What philosophy should guide these marketing efforts? What weights should be given to the interests of the organization, the customers, and society?”8 Two of the philosophies he discusses are the “product” and “marketing” concepts. In essence, these concepts are really worldviews, as depicted in Figure 5.4, the Product focus worldview, and Figure 5.5, the Marketing concept worldview.

Figure 5.4. Product focus worldview.

Kotler says “The product concept holds that consumers will favor those products that offer the most quality, performance, and features. Managers in these product-oriented organizations focus their energy on making good products and improving them over time.”9 In contrast, “The marketing concept holds that the key to achieving organizational goals consists in determining the needs and wants of target markets and delivering the desired satisfactions more effectively and efficiently than competitors.”10

Product Worldview

The core belief of the product focus worldview is the product. Peripheral beliefs emphasize production efficiencies, product quality research, and relationships with channel members and product distribution. A salient characteristic of the product focus worldview is an “inside-out” versus “outside-in” perspective. Management that adopts an inside-out perspective of marketing focuses its attention primarily on the company and secondarily on the markets it serves. According to Wharton Marketing Professor George Day:

Companies that have adopted an ‘outside in’ strategy are those with a focus on creating and keeping customers by delivering superior customer value. They do that by standing in the customer’s shoes and viewing everything the company does through the customer’s eyes. Think of customer value as the lens on the strategy. ‘Inside out’ thinking, on the other hand, begins by asking, ‘What are we good at? What are our capabilities and products? How can we use our resources more efficiently?’ It’s a resource-based view of the firm that is inherently limiting because it means the company is slow to respond to major changes in the market.11

A perfect example of the product-focus worldview has been Nokia’s performance in the United States since the turn of this new century. In the early 2000s, I conducted a considerable amount of marketing research for Nokia and its director of consumer insights, Mark Daniels. From the late 1990s until March of 2002, Nokia’s market share gradually increased from single digits to 35% of cell phone handsets. Consumers found Nokia’s modern looking, mono-block designs attractive—the phones looked like small bars of soap—and the phone’s product quality, exceptional. “Flip” or “clamshell” phones began appearing in the market by the mid-1990s and by the early 2000s began to significantly erode Nokia’s market share. By 2009, Nokia’s market share plummeted to 7%. As Kevin O’Brian reported in the New York Times:

Nokia did not anticipate changes in American consumer tastes, like flip phones and touch screens, said Neil Mawston, an analyst in London with Strategy Analytics. More crucially, perhaps, it also based its models on a European communications standard called GSM when roughly half the United States market—including the customers of Verizon Wireless and Sprint Nextel—uses the CDMA format. ‘Nokia, at the height of its success, decided not to adapt its phones for the U.S. market. That was a mistake,’ said Ari Hakkarainen, a Nokia business development executive from 1999 to 2007. ‘They are still trying to recover from this.’12

Clearly, there are multiple causes for Nokia’s market share decline; however, a significant factor was the company’s reluctance to embrace CDMA technology, and to change their phone’s design to the trendier clamshell form because senior management truly believed that consumers would continue to purchase their product.13 This belief was held in the face of objective marketing research that Daniels was conducting at the time revealing the clamshell design was gaining acceptance quicker than other cell phone forms. Clamshell phones may make inroads, senior executives thought, but not to the extent that Nokia’s market share would return to single digits. In short, Nokia believed their level of brand equity with the consumer would carry the day, as it had in the recent past. This was an unjustified belief.

Notice how Nokia’s worldview shaped managers’ views of reality and caused them not to apply sound principles of scientific reasoning to their marketing decisions. First, by hanging on to the belief that they were manufacturing a solid, high-quality cell phone (vainly so, after their market share peaked in 2002), they failed (or stubbornly refused) to see how US consumers’ tastes in cell phone design were evolving. Second, they failed to recognize the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher David Hume’s Problem of Induction, which states that patterns in the world—including markets—do not necessarily repeat themselves. We will discuss the Problem of Induction at some length in a later chapter. For now it is sufficient for you to know that patterns or regularities we observe in markets in and of themselves contain no information on cause-and-effect relationships. Nokia, however, felt that those factors that had influenced consumers to prefer the Nokia brand in the past would continue to do so into the future, reflecting a very product-focused and myopic worldview.

Marketing Concept Worldview

In contrast, refer to Figure 5.5. The core belief of the marketing concept worldview is customer needs and wants. Peripheral beliefs emphasize differentiating the company’s products from competitors on factors that influence consumer brand selection, segmenting markets, satisfying customers, and conducting marketing research. What can be a better example of the marketing concept worldview than Apple Inc., especially regarding the design, layout, and service in its retail stores? It’s all about the customer.14

Figure 5.5. Marketing concept worldview.

Did you know that, in a single quarter, more consumers visit one of Apple’s 326 stores worldwide than have visited Disney’s four largest theme parks in all of 2010; that store sales per square foot are nearly $4,500, surpassing Tiffany & Co. ($3,000), luxury brand Coach Inc. ($1,800), and big box retailer Best Buy ($900); or that Apple has a retail outlet inside the Louvre in Paris?15

The core of the marketing concept worldview is customer needs and wants. This philosophy permeates Apple’s retail store sales training, which embraces the philosophy of helping consumers find the right technology to fill their needs and wants. As characterized by Don E. Schultz, professor (emeritus-in-service) of integrated marketing communications at Northwestern University, “Apple isn’t trying to sell you anything in its stores; it’s trying to help you solve problems and use technology, and to show off the latest innovations to the tech-savvy and get the ‘digital immigrants’ up to speed. In fact, Apple retail employees are taught how not to sell. Apple people are there to help and it shows, in the store and in the sales results.”16 Additionally, consider some of the instructions Apple gives to its retail store employees, recently brought to light by The Wall Street Journal reporters Yukari Iwatani Kane and Ian Sherr:

• Look for the underlying cause of the person’s reaction. Is it frustration, fear, confusion, etc.?

• Reassure the customer that you are here to help?

• Listen and limit your responses to simple reassurances that you are doing so. ‘Uh-huh,’ ‘I understand,’ etc.

• Take notes. Even when the person is venting, they are often providing important details. It will save time later and help you listen without interrupting.

• Acknowledge the customer’s underlying reaction. ‘I can certainly understand how frustrating this can be.’ ‘I know this can seem very confusing.’17

Earlier, I quoted Steven Jobs’s lack of enthusiasm for marketing research, which is one of the peripheral puzzle pieces in Figure 5.5. But remember that the peripheral puzzle pieces can change and not compromise the integrity of the worldview. Recall that a discovery of a sixth planet would not have compromised the Aristotelian worldview that Earth resides at the center of the universe. The fact that Steven Jobs did not believe in formal marketing research does not take away from the company’s consumer focus.

When you contrast the above stories of Nokia versus Apple, you can see the significance that worldviews can have in how organizations are managed and directed. Ironically, both Nokia and Apple want to be successful companies, but their philosophy and beliefs about how to run their organizations have taken them on two very different paths. Nokia was (and some would say still is) product focused. From Nokia’s perspective, they were making a good product that, functionally, delivered what the consumer wanted. Nokia did not appreciate the intangible characteristics of their product offering—how much consumers valued the intangible “cool” factor. Nokia’s beliefs about how to run their organization, which reflect the product worldview—gave more consumer-oriented competitors such as Samsung and Apple an opportunity to erode Nokia’s market share.

The power that worldviews have in shaping and directing our behavior lies in their central core conviction. For Aristotle, it was the belief in Earth as the center of the universe. For product-oriented companies, it is the importance placed in producing a quality product as defined by the people running the company. For marketing-concept-oriented firms, the focus is on identifying and meeting consumer needs and wants.

Worldviews Affect Actions

As the late twentieth-century philosopher John Dewey said, a central core belief “commits him who holds it to thinking in certain specific ways…and prescribes to him actions in accordance with his [core belief].”18 Consider the various corporate stories I have related to you so far in this book. Brunswick was bent on finding outlets for its Mercury Marine engines (a product-concept focus) and saw Sea Pro as an opportunity in the saltwater boat market. Nokia was initially offered the technology that Motorola eventually purchased to make its Razr phone, which sold more than 100 million units in its first three years on the market,19 and it refused a deal with Qualcomm to develop a CDMA “chip” for Nokia cell phones sold in the United States, which effectively kept most of Nokia’s phones out of Sprint and Verizon stores. In both instances, a centrally held belief dictated Brunswick’s and Nokia’s behavior. This is why it is so critical to understand the concept of a worldview, how a network of beliefs form these worldviews, how worldviews influence how we interpret the world, and, ultimately, shape and influence our actions. The futures of Brunswick, Nokia, and Borders book stores, which I commented on in Chapter 1, could have been dramatically different had senior management’s actions been driven by knowledge rather than by unjustified beliefs.

Chapter Takeaways

1. A worldview is a system of beliefs that affects how we interpret realty. As such, it can shape and direct our actions.

2. Worldviews can be convincing, even though they are wrong. With only the unaided eye, it is impossible to disprove the hypothesis that Earth is at the center of the universe. The reason for this is threefold: (1) casual observation of the sky shows that the sun, moon, planets, and stars revolve around our planet; (2) many mathematical models were developed from the time of the Greeks through the mid-sixteenth century, based on the geocentric view of the universe, that could predict fairly well the future positions of the planets; and, (3) we see the same pattern of stars in the night sky when Earth is at opposite sides of the sun.

3. Whether tacitly or explicitly, senior managers have a philosophy or worldview that guides how they run the organization. Two of these are the product focus and the market focus worldviews. In the product focus worldview, management’s perspective is “inside-out.” Executives place emphasis on product quality, distribution, and cost management. Rarely do such companies conduct formal marketing research. In the market focus worldview, management’s eye is on understanding customer needs and wants. These companies segment their markets, target the most attractive segments, and seek to differentiate their products from competitors’.

4. Nokia is an example of a product-focused company, witnessed by its experiences from the late 1990s to the present. Managers’ belief in the quality of their product and their brand’s equity in consumers’ minds caused them to ignore the market’s demand for CDMA-type and newly designed phones. They truly were looking at their U.S. markets through rose-colored glasses.

5. Apple is an exemplar of the market focus worldview, especially with respect to their “brick-and-mortar” stores. Ironically, managers place less emphasis on “selling” and more on helping consumers solve problems via their technology.

6. A worldview’s core belief not only shapes the peripheral beliefs in the worldview, but also necessarily affects individual and organizational behavior. The marketing landscape is littered with companies who have embraced the product focus worldview and suffered all the more because of it—Nokia, Brunswick, Kodak, Polaroid, Borders, Elgin National Watch Company…the list is long. What caused these failures? Companies mistaking beliefs for knowledge of what the customer wanted.

Does Your Organization Subscribe to the Marketing Concept Worldview?

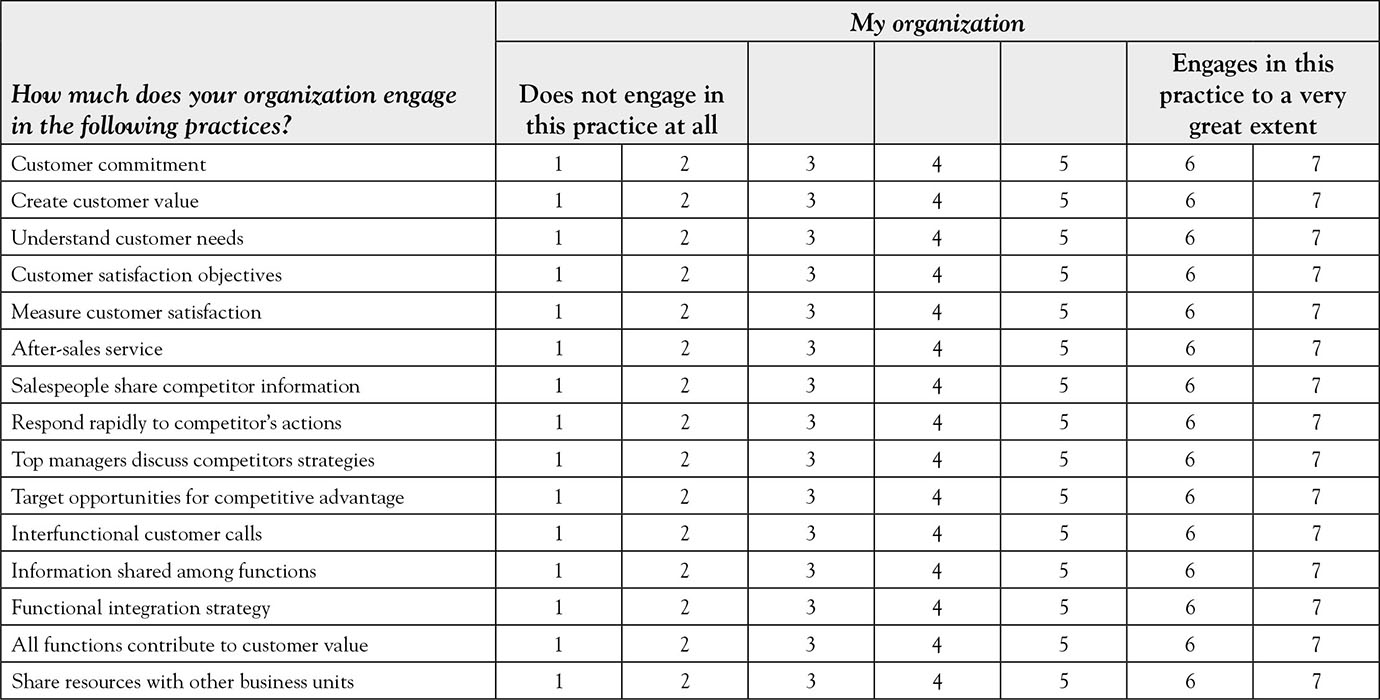

Research shows that there is a positive relationship between organizational performance and the extent an organization is market oriented.20,21 You can examine how market oriented your organization is by completing the short questionnaire below.22 You may want to consider having several members of your marketing team complete the questionnaire to examine the extent individual perceptions of your organization’s market orientation is congruent or divergent. Evidence that your organization subscribes to the market focus worldview is indicated by having an average score of 5 or higher across all 15 items of the scale.