Segmenting Your Market Based on Willingness to Pay: Third-Degree Price Discrimination Strategies

Third-degree price discrimination exists when different prices are charged to individuals who can be grouped according to their characteristics. The assumption is that price sensitivity and willingness to pay might differ across groups of individuals with readily identifiable characteristics. Examples of third-degree price discrimination include senior citizen discounts, discounts for children, etc. The key distinction between second- and third-degree price discrimination is that, in the former, the market segments cannot be recognized ex ante. Hence, the firm creates a pricing structure that allows buyers to self-select. In contrast, the firm has some ability to distinguish willingness to pay before-the-fact, and therefore, sets its prices based on the inferred willingness to pay for each market segment.

To illustrate, a college athletic department knows that some of its football fan base is made up of rabid fans whose life revolves around the football program. Other fans are interested in football and are willing to pay to go to the games, but may have a lower willingness to pay. Unfortunately, the department has no way to discern the rabid fan from the fair-weather fan. Suppose, for example, the department infers that rabid fans are willing to pay $50/ticket but fair-weather fans are not willing to pay more than $30. Moreover, rabid fans can be counted on to attend every game regardless of the weather or win–loss record of the team whereas the fair-weather fans are not likely to buy tickets if the weather is bad or if the team is having a bad season. Suppose the athletic department attempts to discriminate between the groups by offering season tickets for $300 (or $50/ticket) and individual tickets for $30. The athletic director theorizes that fair-weather fans would not be willing to buy a set of season tickets at $30/game because they prefer to make purchase decisions one game at a time. Rabid fans, on the other hand, will always choose to attend every game and have a greater willingness to pay.

If the athletic department attempts to implement this pricing strategy based on its inferences on the two groups’ willingness to pay, it will likely fail. Even though the rabid group may be willing to pay $300 for season tickets, it can opt for six $30 tickets instead and save $120 in doing so. The problem is that, even though the athletic department may be correct in its inferences regarding willingness to pay between rabid and fair-weather fans, it cannot discern who belongs to which group before-the-fact.

On the other hand, suppose the athletic department assumes that its students, due to their lower incomes, have a lower willingness to pay relative to its nonstudent fan base. To illustrate the distinction, examine the demand schedule in Table 7.1. The demand schedule does not distinguish the students from the nonstudents. Assuming the marginal cost of a seat is equal to zero, the department will maximize revenues by charging a price of $75 and earning revenues of $3,525,000 million per game.

Table 7.1. Overall Demand for Tickets

|

Price $ |

Quantity |

Revenues $ |

|

100 |

31,000 |

3,100,000 |

|

75 |

47,000 |

3,525,000 |

|

50 |

58,000 |

2,900,000 |

|

25 |

72,500 |

1,812,500 |

|

10 |

90,000 |

900,000 |

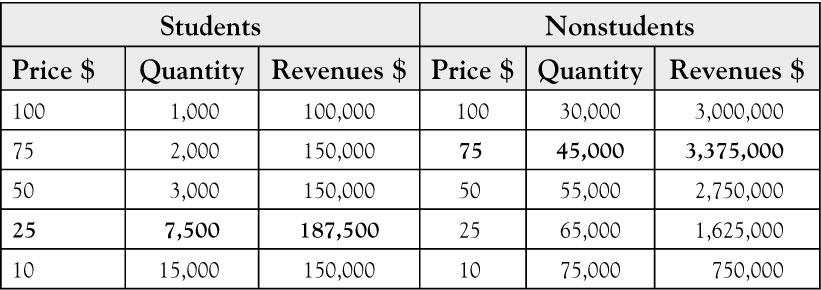

Suppose, however, the market demand schedule illustrated in Table 7.1 can be broken down into students and nonstudents. Assume the students have a lower willingness to pay. The corresponding demand schedules are shown in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2. Segmented Demand for Tickets

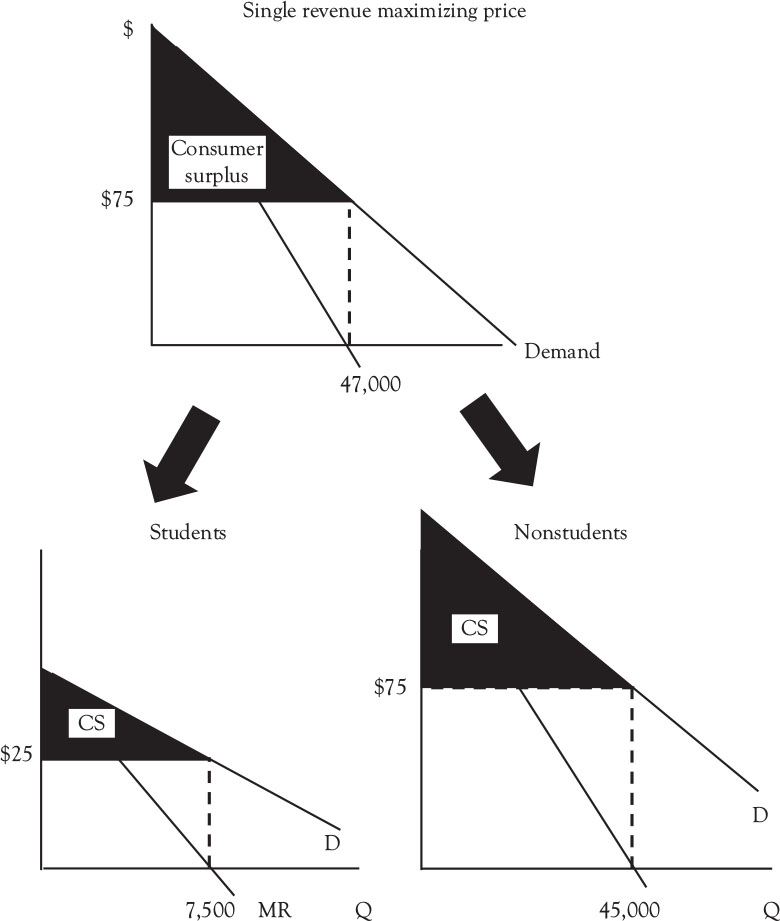

Note that at the revenue-maximizing price of $75 only 2,000 students will buy tickets. Suppose the athletic department decided to establish two ticket prices: one for student and the other for nonstudents. Under the two-tiered pricing scheme, nonstudents would continue to pay $75, but student tickets would be priced at $25. By setting a lower price for the more price-sensitive group, the athletic department is able to increase its revenues by $37,500. The solution is illustrated in Figure 7.1. As the figure indicates, by separating the overall market into two market segments based on price elasticity, the more price-sensitive group pays a lower price than the less price-sensitive segment, causing overall revenues to rise.

Figure 7.1. Graphical representation of third-degree price discrimination.

Earlier, we noted the importance of preempting opportunities for consumers to resell the good. We can revisit that concept in the context of third-degree price discrimination. To assure the more price elastic group does not re-sell the good, the firm has to be somewhat creative. In the case of the student tickets, the athletic department can create tickets with the words “Student Ticket” or a ticket with a different color. In that fashion, enforcement at the gate will come easier: if a 40-year old man shows up at the gate with a “student ticket,” the attendant can ask to see a student ID.

Groupon combines elements of both second and third-degree price discrimination. Groupon offers daily group/coupons in its markets. If enough people sign up for the discount, they all receive it; otherwise, no one gets the deal. From the retailers’ perspective, Groupon represents a convenient vehicle for third-degree price discrimination. By subscribing, consumers label themselves as price-sensitive and are offered a discounted price relative to nonsubscribers. From Groupon’s perspective, its business model is one of second-degree price discrimination. Rather than to identify price sensitive customers based on demographic characteristics, it simply allows consumers to self-select: those are relatively price sensitive subscribe to the service whereas less price sensitive consumers do not.

The Groupon business model also limits arbitrage possibilities. First, subscribers must prepay for the discount. Second, they must agree to the limitations of the offer (i.e. limit one per person). Third, the discounted deals have expiration dates. Groupon Now deals, for example, must be used within 24 hours. Note how the three elements combine to minimize re-selling. By prepaying, the subscriber incurs risk: if he is unable to find someone to re-sell the product or service, he suffers a loss. The limitations of the deal and the expiration dates make it more difficult for the subscriber to re-sell the deal at a profit.

Summary

• Third degree price discrimination exists when firms divide customers into groups based on their price sensitivity and charge separate prices to each group. Examples include senior citizen discounts and discounted prices for children.

• For third degree price discrimination to succeed, the firm must be able to readily identify each group and be capable of subverting opportunities for buyers to purchase the good and resell it.