Dynamic Pricing and E-Commerce

Pricing in the Age of Information Technology (IT)

Dynamic pricing is a new name for an old practice. At its heart, dynamic pricing is price discrimination in the world of IT. The fixed-price system that we are most familiar with is actually a relatively recent phenomenon. Before the Industrial Revolution led to assembly lines and large inventories, first-degree price discrimination was the rule rather than the exception. Merchants, rather than large corporations, offered goods and services. Price tags were never affixed to goods and it was up to merchants to extract consumer surplus through haggling.

The seeds of the fixed-price system sprouted when John Wanamaker opened his “Oak Hall” clothing store in Philadelphia in 1861 and promoted his revolutionary “One price and goods returnable” concept. The emergence of factories, assembly lines, and inventories caused fixed prices to become the norm.

In both the haggling and single price world, buyers and sellers sought a mutually acceptable deal. The seller knew that the buyer could take his business elsewhere and the buyer knew that if he didn’t make a good enough offer, the seller could sell to another customer. But price comparisons entail “shoe leather.” Buyers had to go from store to store to gauge the prices charged by other merchants. And the merchants had to hoof it from place to place to assure their prices were competitive.

Economists usually describe “perfect competition” as a market structure in which many buyers and sellers have perfect information about the prices charged by each firm for an identical good. Absent the geographical constraints of door-to-door price comparisons, perfect competition describes a world in which the forces of supply and demand establish a single price that all buyers and sellers must accept. If a seller attempted to charge any price about the market price, it would lose all of its customers to lower priced competitors.

Although perfect competition is used simply as a model to describe a highly competitive, albeit hypothetical marketplace, the growth of the Internet seemed to give promise that the “law of one price” could indeed prevail. Consumers could compare prices instantaneously with sales shifting to the low-bidder. In such a cut-throat atmosphere, prices were certain to converge to a single figure.

The Internet did not cause the “law of one price” to evolve as predicted. Rather, the World Wide Web became the perfect dispatcher of gains from trade in which innumerable buyers and sellers could, online, find a mutually acceptable price. The price could vary by day, by hour, by minute, and even by customer. “Real-time” got “real fast.”

Dynamic pricing is not limited to e-commerce. IT allows brick-and-mortar stores to gauge consumer preferences and their willingness to pay faster than ever before. Beyond increasing revenue and profits, dynamic pricing allows firms to reallocate demand to manage scarce supply constraints. Dynamic pricing is especially useful for goods and services that are perishable. Once a plane leaves the runway, the empty seats cannot be filled. However, perishability is not limited to airlines and hotel rooms. Clothing is seasonal in nature and “perishes” once demand is exhausted. The same can be said for consumer electronics, which become obsolete as new models become available.

There are two categories of dynamic pricing. Posted prices are, as the name implies, prices that customers observe. Price discovery refers to auction mechanisms that allow consumers to determine their own prices.

Posted Prices

Posted prices, whether for e-commerce or traditional stores, can be enhanced by IT, which allows retailers to make pricing and inventory decisions for thousands of products. Consider clothing, which often has a seasonal demand. In the pre-IT days, a line of clothing might have posted fixed prices for up to three months. End-of-season fire sales inevitably followed, with substantial discounts. But with today’s technology, brick-and-mortar prices can be raised or lowered on nearly a daily basis, and online prices can change several times/day. When inventory tracking systems show demand for a given line is increasing, prices rise. When a line is moving slowly, prices decrease. In doing so, the firm can use variable pricing to manage its scarce inventory space.

E-commerce provides even more promise for dynamic posted prices. In the pre-Internet days, it was prohibitively costly for firms to attempt to gather customer-specific information and to monitor their buying habits. Mail-order catalogs used zip codes to adjust their prices based on inferred willingness to pay in wealthier regions, but even in those cases, price changes implied creating new catalogs. For retail outlets, price changes meant costly re-tagging.

Today, computer “cookies” allow websites to record the user’s previous interactions with the website. “Click-stream” technology allows firms to view user’s paths as they browse advertisements, different web pages on the site, and links to other sites. Thus, the retailer not only knows where its customers live, but their history of past purchases, and what goods they’ve loaded (and unloaded) from online shopping carts. Some online retailers, such as Amazon, may require potential buyers to load goods into the shopping cart just to see their price. Personalized recommendations can be offered to prospective customers based on their past viewing or shopping habits.1 Unlike costly re-tagging, online prices can be changed by the click of a mouse. This allows for a much more efficient and fast means to segment customers by their willingness to pay.

Determining the optimal markup for online pricing follows the same premise of marginal cost pricing, but with a different twist for the online venue. In addition to wholesale prices, incremental costs include clickthrough fees on price comparison sites that can range from $0.40 to $1.50. Moreover, conversion rates (the probability that a click will lead to a sale) average only 3%, meaning that a great many clickthrough costs will be incurred for each sale.2 To illustrate, suppose an online product can be purchased from the wholesaler for $25. Suppose a price comparison site charges $0.50 per click with a conversion rate of 4%. This implies that roughly 25 clicks are necessary to generate a sale (1/.04). Correspondingly, then, the marginal cost of the product is $25 + $0.50 × 25 = $37.50.

The optimal markup depends on the price elasticity of the customers. Earlier in the text, we discussed the potential problems associated with trying to measure price elasticity. Specifically, the calculation assumes the two price/quantity combinations lie on the same demand curve. If they lie on two different demand curves, the coefficient estimate will be biased and could lead to disastrous implications. In the world of traditional pricing, this problem is particularly likely, as firms rarely change their prices unless an outside factor (i.e. one that shifts a demand curve) prompts them to do so. Now, with the ability to change prices rapidly, firms can easily experiment with various prices and gauge the response of consumers. In doing so, the estimated elasticity coefficient will be more realistic.

Beyond varying prices to measure elasticity, online retailers should also change prices to keep their competitors on their toes. The Internet not only allows buyers the chance to comparison shop, it allows firms to monitor the prices of their rival firms. If a firm’s price is too stable and predictable, rivals can undercut their prices slightly to allow them to show up as the lowest-priced firm on price comparison sites. A better strategy might be the randomized pricing strategy of undercutting a competitor one day while returning to the original price the next.

Firms with an online presence must realize that online consumers are product-oriented rather than firm-oriented. WalMart may compete with K-Mart in the mass merchandise industry, but online consumers who are looking for a new television are likely to type “televisions” into their search engines rather than type in “WalMart” and seek out its televisions. If a firm only concentrates on its traditional rivals rather than its product-specific competitors, it may find itself consistently undercut in price.

Online retailers should be aware, however, that consumers are wise to such schemes and do not always take kindly to them. In 2000, Amazon.com customers were not pleased to learn that some of them were paying different prices for the same DVDs. One customer deleted the cookies that identified him as a frequent Amazon shopper and he saw the price of a DVD fall from $26.24 to $22.74. Amazon responded that it was part of a “price test” rather than dynamic pricing and offered a refund to customers who paid higher prices. A survey implemented by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania in 2005 revealed that 76% of respondents stated it would bother them if others paid less than they did for the same products.3 Eighty-seven percent disagreed with the statement “It’s OK if an online store I use charges people different prices for the same products during the same hour.” Even more revealing is that 72% disagreed with the following statement: “If a store I shop at frequently charges me lower prices than it charges other people because it wants to keep me as a customer more than it wants to keep them, that’s OK.” In fact, 64% did not know that it was legal for an online firm to charge different prices to different customers during the same time of day. Seventy-one percent did not know that it was legal for an offline firm to do the same.

Price Discovery

An alternative to posted prices, made possible via e-commerce, is price discovery. Price discovery is when the consumer takes an active part in determining the price. A plethora of online retailers such as eBay make products available by auction.

English Auction

The English auction is the type of auction most people are familiar with. A single good is made available for sale at an opening bid. Once the bidding stops, the high bidder purchases the good at a price equal to the amount of the bid. Some auction sites allow bidders to submit a price that represents their maximum bid. If a given bidder is outbid, his bid rises automatically. If the latest bid exceeds his reservation price, the bidder drops out of the auction.

Dutch Auction

The Dutch auction is essentially the English auction in reverse. The seller initially offers the good at a higher price than buyers are likely to be willing to pay. He gradually lowers the price until he finds a buyer. The Dutch auction was utilized by Google in its initial public offering. The search engine giant initially offered nearly 20 million shares at a price between $108 and $135 per share and gradually lowered it until it eventually reached a price of $85. The Dutch auction raised $1.67 billion for Google.4

First-Price, Sealed Bid Auction

A variation on the English auction is the first-price, sealed bid auction. Here, the bidders submit a bid without knowing those made by other bidders. The auctioneer gathers up the bids and awards the purchase to the highest bidder. The distinction between the first-price, sealed bid auction and the English auction is that, with the sealed bid auction, the bidders cannot follow the progress of the bids because they are unknown. In addition, whereas the bidder in the English auction can update his bid during the auction, the bidder submits only one bid in the first-price, sealed bid auction.

Second-Price, Sealed Bid Auction

The second-price, sealed bid auction (also called the Vickrey auction) bears similarity to the first-price, sealed bid auction to the extent that each bidder submits one sealed bid with the high bidder winning the auction. The difference is that the winning bidder pays a price equal to the second highest bid, rather than his own winning bid. Google uses a second-price, sealed bid auction via AdWords for its online advertising, which annually generates more than $20 billion. Advertisers submit bids in advance based on search terms or keywords. Rather than bid on the price of an impression, advertisers bid on the price they were willing to pay for each click on the advertisement. Sidebar advertisement slots on a results page are sold off in a single auction. Consistent with second-price, sealed bid auctions, the price paid by the winning advertiser is not equal to the winning bid, but rather, is based on the next highest bid.

The AdWords auction is more complex than simply awarding an advertisement to a high bidder. The critical element of online advertising is that the advertisement is tailored to the user’s search. To do this, Google tabulates quality scores that determine the relationship between the advertisement and the keyword(s), the quality of the results page to which the advertisement is linked, and the percentage of times users actually click on the advertisement. Advertisement ranks are tabulated by multiplying the advertiser’s maximum bid by its quality score. In this manner, advertisers with low quality scores must bid higher to achieve a higher rank. The advertiser with the highest advertisement rank pays the amount bid by the second highest bidder.

To illustrate, suppose two prospective advertisers bid for an advertisement slot. Advertiser A submits a maximum cost per click (CPC) of $2 whereas advertiser B submits a bid of $2.50 CPC. Suppose the quality scores for A and B are 10 and 7, respectively. The corresponding advertisement ranks are $2 x 10, or 20 for advertiser A, and $2.50 x 7, or 15 for advertiser B. Note that even though B is willing to pay a higher CPC, A has the higher advertisement rank. To determine the price A must pay, the second highest advertisement rank (or 15 for B) is divided by A’s quality score, resulting in a CPC of 15/10, or $1.50.

The auction is mired in economic theory; in fact, noted Berkeley economist Hal Varian took a leave of absence to become Google’s chief economist. The auction was so successfully that Google eventually chucked most of its sales force, which drummed up advertising revenue the old-fashioned way, by wining and dining prospective advertisers, and converted everything onto the online advertisement auction.

The Economics Behind Auctions

Our goal is to determine which auction mechanism generates the most revenue. To understand the incentives underlying auctions, we need to distinguish between private value auctions and common value auctions. In a private value auction, the bidder wants the good for his personal use, such as bidding for a painting. In a Sotheby’s auction of contemporary art, each prospective bidder’s reservation price depends not only on the individual’s ability to pay, but the satisfaction the bidder derives by owning the work of art. This could vary widely from person to person. In a common value auction, the bidder seeks a good that will generate money for the owner, such as bidding for the rights to an oil field. Hence, the value of the good being auctioned off has approximately the same value to each bidder. If the amount of oil that lies beneath the land were known with certainty, the oil revenue would be largely the same for all bidders. However, because the richness of the land is uncertain, each bidder must estimate the expected revenue from owning the oil rights.

In a private value auction, the bidder knows his reservation price, but does not know the reservation price of the other bidders, which can vary widely according to their tastes. In the English auction, he remains in the bidding until the price rises to a level above his reservation price. At that point, he drops out of the bidding.

To illustrate the various incentives, suppose we have two sports fans, Josh and Jake, who are bidding for an autographed photo of LeBron James. Josh has a reservation price of $200 and Jake has a reservation price of $225. It should be intuitively obvious that in the English auction, the price will rise until Jake bids a price that exceeds $200. In theory, Jake could win with a bid as low as $200.01, providing Jake with consumer surplus equal to $24.99.

We can analyze the English auction strategy from both the bidders’ and auctioneer’s perspective. From the bidder’s point of view, the clear strategy is to remain in the auction until the current bid exceeds one’s reservation price. From the auctioneer’s perspective, the English auction allows the high bidder to walk away with consumer surplus. The winning bid need not be equal to the winner’s true valuation of the good; it need only exceed that of the second-highest bidder.

Let’s examine the same scenario, but with a second-price, sealed bid auction. In this case, Josh and Jake cannot observe the progress of the auction. Each bidder must submit exactly one bid. The high bidder wins the auction, but pays a price equal to the bid submitted by the second-highest bidder. Josh values the photo at $200 and Jake is willing to pay up to $225, but neither bidder knows the other’s valuation or bid.

What should each person bid? We can begin by acknowledging that each party understands that it will lose the auction if the opponent submits a higher bid. But given that the winning bidder does not pay his own bid, but the second-highest bid, should he submit a bid that is equal to, less than, or higher than his reservation price?

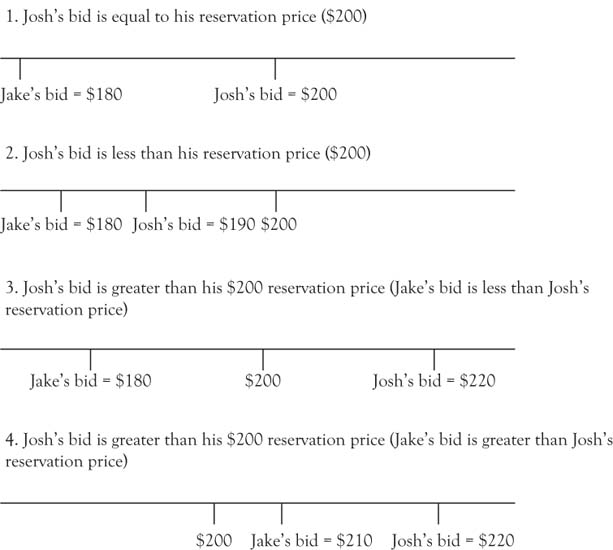

Figure 8.1 illustrates the decision from Josh’s perspective. The figure shows four circumstances in which Josh’s bid wins the auction. In the first instance, Josh submits a bid equal to his reservation price ($200). He can only win if Jake submits a bid less than $200. Assuming this is the case then Josh wins the auction, but pays the amount of Jake’s bid ($180). Hence, by bidding his valuation, Josh walks away with the photo and $20 in uncaptured consumer surplus.

Figure 8.1. Winning bids in a second-price, sealed bid auction.

In the second scenario, Josh submits a winning bid ($190) that is less than his reservation price. As with the first scenario, Josh wins the auction and pays a price equal to Jake’s bid ($180), allowing him to have $20 in uncaptured consumer surplus. In comparing the first two scenarios, one should see that it is unambiguously in Josh’s interest to submit a bid equal to his reservation price. To win, his bid must exceed Jake’s, but the price Josh pays is equal to $180 (Jakes’ bid) regardless of his own bid. Because Josh cannot control Jake’s bid (and, in fact, does not know Jake’s bid), raising his own bid to reflect his valuation of the photo increases his likelihood of winning the auction without affecting the price he pays if he wins.

Scenarios three and four illustrate the possibilities if Josh wins with a bid that exceeds his reservation price. Josh might consider this possibility because he will not have to pay the amount of his bid if he wins. In scenario three, Josh submits a bid of $220 and Jake submits a bid of $180. Because Josh submitted the higher bid, he wins the auction, pays the amount of Jake’s bid, and walks away with $20 in uncaptured consumer surplus. Note that the outcome is identical to the case in which Josh submitted a bid equal to his valuation; he still wins the auction, he pays Jake’s bid, and he earns $20 in consumer surplus. Thus, it did not benefit Josh to submit the higher bid.

Scenario four indicates the worst case scenario for Josh. He submits a bid of $220 and Jake submits a bid of $210. Josh wins the auction, but must pay a price that exceeds his valuation of the photo. In comparing scenarios three and four, we can see why Josh would never submit a bid that exceeds his reservation price. Either the result is identical to when he bids an amount equal to his reservation price, or he wins the auction, but must pay more than what the photo is worth to him.

Combining all four scenarios, it should be obvious that Josh should submit a bid equal to his reservation price. We could re-create an identical set of circumstances for Jake, but the results will be the same. Not knowing what Josh will bid, Jake is unambiguously better off submitting a bid equal to his own valuation ($225). Jake will win the auction and will pay $200 for the photo (i.e. Josh’s bid).

Note that the results of the second-price, sealed bid auction are virtually identical to those of the English auction. In the English auction, the bids rise until Jake submits a price that exceeds Josh’s reservation price. In theory, this could be as low as $200.01. With the second-price, sealed bid auction, both parties submit a bid equal to their reservation price, Jake wins the auction and pays $200, which is Josh’s valuation of the photo.

Now let’s compare the results of the Dutch and first-price, sealed bid auctions. Recall that in the Dutch auction, the price gradually falls until one of the bidders claims the good. In the first-price, sealed bid auction, the bidders submit a single bid without knowing the bids submitted by the other bidders. The high bidder pays a price equal to his bid.

Continuing with Josh and Jake, the Dutch auction begins with a price that exceeds each party’s valuation. Because the winning bidder must pay the price at which he bids, it makes no sense for either party to claim the good until the price drops to his reservation price. Thus, Jake will hold off until the price falls to $225. Should he claim the photo and pay $225 or should he hold off in the hope that he can get the photo at a lower price?

This is what distinguishes the Dutch auction from the English or second-price, sealed bid auctions. In the English auction, Jake will gradually up the bid until Josh drops out of the auction. Although Jake does not have information as to Josh’s bid in the second-price, sealed bid auction, his incentive is to submit a bid equal to his reservation price, knowing that if he wins, he will pay the second-highest bid and earn consumer surplus.

But the Dutch auction requires a guessing game on Jake’s part. He knows that Josh’s reservation price does not exceed $225 (otherwise Josh would have won the auction), but does not know with certainty the price that will cause Josh to claim the photo. If Jake claims the photo at $225, he earns no consumer surplus, but if he allows the price to fall, he may still be able to win the auction and pay a lower price. Thus, allowing the price to continue to fall involves a trade-off: on the one hand, it might allow Jake to win the auction at a lower price. On the other hand, by allowing the price to drop, Jake gambles that Josh will claim the photo. If Jake had perfect information, he would know that he could wait until the price fell to $200.01. Absent such knowledge, Jake must weigh the benefits of allowing the price to fall against its costs.

Interestingly, the bidders’ incentives in the first-price, sealed bid auction are identical to those of the Dutch auction. As with the Dutch auction, the winner must pay the amount of his bid; hence, it would make no sense for a bidder in the first-price, sealed bid auction to submit a bid that exceeds his reservation price. In addition, the bidder has no knowledge of the other bidders’ valuation at the time he submits a bid.

The thought process, therefore, replicates that of the Dutch auction. Because Jake will never submit a bid that exceeds his valuation of the photo ($225), his best chance of winning the auction is to submit a bid equal to $225. However, by submitting a bid that is less than $225, he must balance the decreased odds of winning the auction against the potential benefits of winning the auction at a lower price.

Thus far, we’ve established that the revenues generated from the English auction should be identical to those generated from the second-price, sealed bid auction, and that the revenue generated from the Dutch auction should be identical to that generated from the first-price, sealed bid auction. But which is likely to generate the most revenue: the English/second-price auction or the Dutch/first-price auction?

Perhaps surprisingly, the revenues generated from any of the four auctions should be the same.5 This is predicated on several assumptions. First, the bidders are neutral in their attitudes toward risk. Second, whereas the bidders recognize that reservation prices differ across bidders, they assume that all bidders follow the same set of strategies regarding bids. Just as Jake weighs the benefits of allowing the price to fall below $225 against its costs, so does Josh weigh the costs and benefits of allowing the price to fall below $200. Moreover, the optimal set of bids should be such that, after all bids are simultaneously revealed, no individual bidder can be better off by unilaterally changing his bid. Given these assumptions, bidders in the first-price, sealed bid auction will estimate the second highest bid and submit that figure. Bidders in the Dutch auction will claim the good just before the second highest bidder claims it. On average, therefore, all four auction mechanisms should generate the same revenue.

This finding (called the Revenue Equivalence Theorem) should not be inferred as suggesting that the revenues from the four auctions will be identical, but rather, that they will be the same on average. Because the English and second-price auctions are based on simple strategies and do not involve the guesswork inherent in the Dutch and first-price, sealed bid strategies, the variation in revenues will be smaller with the English and second-price auctions.

Can the firm increase the revenues generated from the auction? Indeed, this can be accomplished in two ways. First, the greater the number of bidders, the greater the number of reservation prices. Logically, therefore, the greater the number of bidders, the smaller the gap between the winning bid and the second-highest bid. This implication should be fairly intuitive. Our analysis suggests that Jake will win the auction and pay a price that equals (or is just slightly more) than Josh’s valuation. As more bidders enter the auction, it would seem rather unlikely that all of them will value the photo less than Josh. If only one of them values the photo more than Josh, the price paid for the photo will rise even if Jake still wins the auction. Moreover, one of the bidders may value the photo more than Jake. If so, another bidder will win the auction and the price will be at least equal to Jake’s bid (or higher if other bidders value the photo more than he does).

Another tool is for the seller to include a minimum selling price. If the bids do not exceed this price, the seller does not sell the item. If the bids exceed the minimum price, the good is sold to the highest bidder with the price determined by the auction mechanism. How can this increase the seller’s revenue? To begin with, one can easily see that the minimum selling price has no impact if at least two bids exceed the minimum. If the minimum selling price for the LeBron James photo is $150 and Josh and Jake value the photo at $200 and $225, respectively, then the Revenue Equivalence Theorem suggests that Jake will win the auction, pay $200 (or $200.01) for the photo, and earn roughly $25 in consumer surplus. But what if the minimum selling price was set at $210? Jake must bid at least $210 to obtain the photo, even though Josh would never have offered to pay more than $200. Jake still wins the auction, but pays $210 and earns only $15 in consumer surplus. Given that the seller does not know the valuations for either Jake or Josh, the only risk incurred by the seller is setting a minimum price that exceeds either valuation. For example, if the seller had established a minimum price of $230, neither individual would have bid for the photo.

Thus far, we have assumed that the bidders in the private value auction were risk neutral. How would the results differ if they were risk averse? In the case of the English auction, risk attitudes do not matter. The bids rise until all of the bidders except one have dropped out. Because losing bids pay nothing, the winner controls the amount of the winning bid. The same is true for the second-price, sealed bid auction. As noted earlier, each bidder has an incentive to submit his own valuation as the bid. This effectively eliminates the role that risk attitudes may play in the auction.

The incentives for bidders in the first-price, sealed bid and Dutch auctions are, however, influenced by risk attitudes. Recall that no bidder would submit a bid that exceeds his reservation price under any of the auction mechanisms. In both the first-price, sealed bid and Dutch auctions, however, the bidder can maximize his odds of winning the auction at an acceptable price by bidding at his reservation price. This is most obvious with the Dutch auction. As soon as the price falls to his reservation price, he can claim the item. With the first-price, sealed bid auction, the bidder can submit his reservation price as his bid. Although he cannot guarantee that he will win the auction, he maximizes his likelihood of doing so without risking that he pays more for the good than what it is worth to him.

As noted earlier, however, rather than volunteer to pay his reservation price, the bidder can allow the price to fall in the Dutch auction (or submit a price that is less than his reservation price in the first-price, sealed bid auction) in the hope that he can still win the auction, but pay a lower price. By choosing this route, the bidder risks that he will not be outbid; hence, trying to win the auction at a lower price is something of a gamble. Risk-averse bidders will be less willing to take that chance. Hence, one would expect risk-averse bidders to submit a price that is closer to their reservation price in the first-price, sealed bid auction (or alternatively, not allow the price to drop as much in the Dutch auction). This implies that the average revenue in the Dutch/first-price, sealed bid auction will be greater with risk-averse bidders than with risk neutral bidders.

In summary, when the bidders are risk neutral, all four auction mechanisms are expected, on average, to generate the same revenue. If the bidders are risk averse, the first-price, sealed bid and Dutch auctions will generate more revenue than the second price, sealed bid or English auctions. What does this suggest for the firm? The implications are that in a private value auction, the firm should use either the first-price, sealed bid or Dutch auction. Assuming the seller does not know the risk preferences of the bidder, the first-price, sealed bid or Dutch will generate the same revenue as the other auction mechanisms if the bidders are risk neutral, but would generate more revenue if the bidders are risk averse.

In a common value auction, the value of the good is roughly the same across bidders, but is not known to any bidder with certainty. Imagine, for example, bidding for a jar of pennies. All bidders see the jar, but none of them know with certainty how many pennies are in the jar; they can only estimate the number. Clearly, in such a scenario, some people will overestimate the number of pennies whereas others will underestimate it. Consequently, if the jar was auctioned off to the high bidder, the winner will be the person who overestimates the number of pennies by the largest margin! Economists refer to this situation as the winner’s curse. One can sense the uneasiness that must come with winning a common value auction. After all, given that the true value of the good must be more or less the same across all bidders, the winner realizes that all of the opposing bidders thought the good was worth less than he did.

Theory suggests that bidders will incorporate the likelihood of the winner’s curse into their bidding strategies and bid more cautiously as a result. The bidder begins by assuming that if he wins the auction, his estimate of the value of the good is probably too high. In essence, he presumes that he would be afflicted with the winner’s curse if he submitted a bid equal to his unbiased valuation of the good. Assuming that the competing bidders think the same way, he submits a bid equal to what he believes is the second-highest valuation.

Winning the common value auction without overbidding is no easy task. It requires the bidder to not only estimate the value of the good, but also the expected error from overbidding. Hence, the bid should be equal to the bidder’s estimate of the true value of the good less the expected error of the winning bidder. The more precise the estimate is, the lower the amount by which one must reduce one’s bid. Using a sports analogy, it is a lot easier to a club to bid for a marginal-free agent than for a star-free agent. In addition to fluctuating performances, professional athletes subject themselves to potential injuries. A star player on the disabled list has no more value to his team than a marginal player on the bench, and may even be worth less. Overestimation errors for marginal players will tend to be smaller than those made with star players. Thus, it’s easier to estimate the value of a player with a relatively short career than it is to estimate the value of a star player whose career may span two decades or two months.

One important distinction between the private value and common value auction is that, whereas the value one places on owning a specific good can vary greatly across individuals, the value of the good in the common value auction should not vary between bidders. This is important because the bids in a common value auction can signal important information to other bidders about the true value of the good.

This can be most easily illustrated in the English auction. A bidder may have formulated a notion of the good’s common value before the auction begins. But if the bids increase at a snail’s pace, and remain well below the bidder’s initial assessment of the product’s worth, the individual may begin to question his reservation price and adjust downward. At the opposite extreme, if the bids rapidly pass one’s own reservation price, the individual may infer that he underestimated the value of the good and should increase his bid. Because each bid conveys useful information as to the estimated values from opposing bidders, the winner’s curse is likely to be less extreme.

In a Dutch auction, the bidders receive no information to help them gauge whether they are overbidding. The same holds true for the first-price, sealed bid auction. They submit a single bid with no ex ante knowledge of the value estimates placed on the good by the other bidders. In both cases, they must pay a price equal to their bid. Although one might infer that the Dutch and first-price, sealed bid auctions will be more lucrative than an English auction, the reverse is true. Bidders tend to be well aware of the potential for the winner’s curse and the lack of opportunities to reassess their estimates in the Dutch/first-price, sealed bid auctions. To avoid the possibility of the winner’s curse, they tend to be more cautious in their bidding than they would have been with the English auction.

From the bidder’s perspective, the second-price, sealed bid auction is modestly better. Although the bidder infers no information as to the estimated values submitted by the other bidders, the price is determined in part by the estimates of the other bidders. This entices him to be less cautious when submitting a bid.

Putting the pieces together, the feature that distinguishes the private value auction from the common value auction is that, in the latter, the good should have roughly the same value to all bidders. Thus, the bids convey useful information as to the true value of the good. Absent this information, bidders tend to bid more cautiously to avoid the winner’s curse. Although the bidders are not privy to the others’ bids in the second-price, sealed bid auction, the fact that the price will be equal to the second-highest bid causes them to be less cautious. Hence, from the seller’s perspective, the English auction tends to generate the most revenue, followed by the second-price, sealed bid auction, and then the Dutch/first-price, sealed bid auction. This rank order remains the same even if the bidders are risk averse.

Summary

• Dynamic pricing has become possible through advances in IT. It allows firms to adjust their prices much more quickly to speed the sale of slow-moving merchandise or otherwise adjust prices to reflect inventories and inventory costs.

• IT allows firms to gather consumer-specific information that allows them to price to each consumer individually online.

• Pricing for e-commerce should include not only wholesale prices, but also click-through fees and conversion rates.

• E-commerce offers a better opportunity for firms to gauge the level of price sensitivity as prices can be altered on a daily basis (or even more frequently).

• Firms listing products for e-commerce should be careful not to make their prices too easy for competitors to monitor. If prices can be monitored too easily, competitors can underprice them by only a few cents and have their product pop up as less expensive on search bots.

• Unlike traditional retail outlets, e-commerce competitors may be product-specific rather than store-specific.

• Price discovery exists when the prospective customer actively assumes a role in determining the price, usually through online auctions.

• In an English auction, the customer who bids the highest gets to purchase the good, with the price equal to his bid.

• In a Dutch auction, the seller puts the product out for auction at a price that exceeds what buyers are willing to pay, and then gradually lowers the price until he finds a buyer.

• In a first-price, sealed bid auction, each bidder submits a sealed bid with no knowledge of the bids submitted by others. The high bidder purchases the good at a price equal to his bid. In a second-price, sealed bid auction, each bidder submits a sealed bid with no knowledge of the bids submitted by others. The high bidder purchases the good at a price equal to the bid of the second-highest bidder.

• In a private value auction, all four auction mechanisms should generate the same expected revenue if the bidders are risk neutral. Sellers can generate more revenue by increasing the number of bidders or by establishing a minimum price for the good. If the bidders are risk-averse, the first-price, sealed bid and Dutch auctions should generate the most revenue, followed by the second-price, sealed bid and English auctions.

• In a common value auction, the good should have roughly the same value to all bidders. Hence, the winning bid often goes to the bidder who overestimated the true value of the good by the greatest amount (winner’s curse). Bidders are aware of the winner’s curse and strategically attempt to incorporate it into their bids.

• In a common value auction, the English auction should generate the most revenue, followed by the second-price sealed bid auction. The first-price, sealed bid auction should generate the same revenue as the reverse and Dutch auctions. The rank order is the same regardless of the risk preferences of the bidders.