CHAPTER 4

Business Schools as Agents of Change: Addressing Systemic Corruption in the Arab World

Abstract

Systemic corruption in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is a serious hindrance to economic growth and business prosperity. Not only does it result in millions of dollars in lost revenue and productivity ever year, but it further slows growth by detracting foreign investment. This chapter argues that business schools in the MENA face a unique opportunity and challenge to serve as agents of change through offering a platform from which to teach integrity, responsibility, and anti-corruption. The chapter begins with a documentation of corruption practices and their peculiar expressions in the Arab World. From there, we present an analysis of the role of business and business education in the fight against corruption and document the “business case” against corruption. Finally, some regional higher education institutions are sampled and documented to highlight current trends in business school education in the Arab region in regard to topics relating to business ethics, corporate social responsibility (CSR), integrity, and anti-corruption. Recommendations are made in light of the findings revolving around the need for universities in the Arab region to introduce courses that sensitize future managers and leaders to the complexities of ethical decision-making. Opportunities and challenges for business schools serving as agents of change in this context will be discussed and a roadmap for action presented for those business schools ready to embark on the journey.

Introduction

We have witnessed over the past 30 years a significant improvement in research and policies aimed at addressing corruption, yet the latter continues to be a subject that is difficult, if not risky, for scholars to pursue. This chapter contributes to the literature on the subject by addressing the intersection of education and corruption. In doing so, it seeks to examine the role that business schools might play in the fight against corruption through relevant education, an anti-corruption platform that has scant mention in the literature. Taking the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region as a case in point, the chapter sheds light on corruption in MENA and makes recommendations for business schools in the region to address corruption through appropriately tailored curricula and peda-gogical techniques.

In analyzing the literature on corruption, especially as it relates to business, the chapter tackles two questions that are likely to be relevant to readers of this book. The first pertains to the business case for adopting an anti-corruption platform and the second one relates to the role of educational institutions in providing the needed cognitive infrastructure to support the fight against corruption. Using the example of corruption in MENA, the book chapter offers numerous examples of pedagogical techniques appropriately suited for buttressing the fight against corruption across the globe.

At a time of critical historical importance for the MENA region, the Arab Spring has heightened citizens’ concerns about fair and representative government, equality and access to opportunity. Corruption is a concern that has been loudly voiced by Arab constituents since the uprisings in Tunisia began in December 2010. The Arab Spring no doubt presents a potent opportunity for the business community to heed the demands of the public at large and respond in-kind with more ethical and fair practices. It is also an opportunity for business schools to reconsider the relevance of their offerings and think about how to more systematically realign their curricula with expressed issues and needs around them.

The book chapter begins by focusing on corruption in the MENA. We document the entrenched and widespread corruption across the region. Then we proceed to examine the relationship between business and corruption. As this edited volume entitled, “Teaching Anti-Corruption—Developing a Foundation for Business Dignity,” suggests the private sector is inherently implicated in the fight against corruption. We show this relationship, first for its own sake, and second, as a value-added for open and transparent society-building and sustainable development. We move from there to address the parallel important role for business schools in the fight against corruption, and then finally back to the MENA region to offer useful suggestions with innovative ideas for relevant classroom instruction to address the corruption epidemic in the region and beyond.

Corruption in MENA

The Arab states1 suffer from pronounced levels of corruption. Indexes such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) measuring levels of corruption in the world give a good indication of corruption in the region.2 Total scores range on a scale from 0 to 10, 10 being least corrupt, 1 being most corrupt. While only measurements of perception are used, over time, the CPI has shown to be a rather accurate measure of actual corruption levels in a given country.3

According to a report of Transparency International issued at the end of 2010, 36% of the population of the Arab world had to pay a bribe to government officials in different positions.4 From obtaining drivers’ licenses, to employment to permits, to job placement through wasta and bribery, corruption permeates the culture of the MENA region.5 Looney notes that both grand and petty corruption are manifest in MENA. The former describes ways in which autocratic rulers steal from the state, in systematic ways such as economic models, awarding state contracts and facilitating private enterprise on their behalf. The latter describes ways that smaller scale corruption manifests in offices and bureaucracies throughout MENA countries. This might entail taking small bribes to expedite government services, falsifying government papers or government officials favoring their family and friends in the distribution of official services.

Table 4.1. Transparency International Corruption Perception Index Scores 20116

Country |

CPI Score |

Country rank |

|---|---|---|

Qatar |

7.2 |

22 |

UAE |

6.8 |

28 |

Israel/Palestine |

5.8 |

36 |

Bahrain |

5.1 |

46 |

Oman |

4.8 |

50 |

Kuwait |

4.6 |

54 |

Jordan |

4.5 |

56 |

Saudi Arabia |

4.4 |

57 |

Tunisia |

3.8 |

73 |

Morocco |

3.4 |

80 |

Djibouti |

3 |

100 |

Algeria |

2.9 |

112 |

Egypt |

2.9 |

112 |

Syria |

2.6 |

129 |

Lebanon |

2.5 |

134 |

Comoros |

2.4 |

143 |

Mauritania |

2.4 |

143 |

Yemen |

2.1 |

164 |

Libya |

2 |

168 |

Iraq |

1.8 |

175 |

Sudan |

1.6 |

177 |

While a comprehensive description of the causes of corruption in the region is beyond the scope of this book chapter, Table 4.2 compiles some of the most important and commonly invoked causes.

Table 4.2. Main Causes of Corruption in MENA

Cause |

Description |

|---|---|

Rentier Economies |

An economic model in which nothing is produced, but something is rented, such as assets like land or oil. This is a defining characteristic of the MENA, which is rich in oil, minerals and metals, as well as remittances from abroad, foreign military, and economic aid, and international tourism.7 These types of economic transactions constitute more than one-third of the MENA economies.8 As with all economic models, rentierism has implications for governance and politics, most notably as international rents decrease the need of tax collection and therefore accountability in government.9 “The culture of rent has negative effects in Arab countries. It is a culture that denigrates effort and prefers intermediation rather than the direct production of real wealth.”10 This thesis is compatible with the existing theories of corruption in developing countries made by scholars such as Rose-Ackerman11 and Shleifer and Vishny12 that show corruption is greater in economic models where bribes can be extracted from rent producing activities. |

Autocratic Regimes |

Theories on the prevalence of corruption show that democratic regimes provide more safeguards against corruption.13 Arab states, since decolonization in the mid-20th century have had a tradition of autrocratic rule.14 This has only recently been challenged in a substantial way, with the Arab Spring protests. “Arab states’ political institutions have been non-representative and non-democratic. In some instances, they are monarchical, and in others they are republics where, in most cases, power was assumed by military-turned civilian rulers via orchestrated elections.”15 Appendix A highlights democracy/freedom scores in the Arab world. |

Quasi Economic Liberalization Welfare States |

The literature on corruption and its causes shows that in times of economic liberalization, opportunities for significant corruption and collusion exist and when corruption occurs in these contexts, growth and the rate of technological change and growth is debased.16 The quasi-economic liberalization facilitated corruption in the Arab states, which in turn has had a negative correlation to innovation, growth, and sustainable development. |

Poverty |

Poverty is a reality of the MENA region for most countries (see Appendix A). GDP per capita in some of the most populous countries is well below levels that contribute to adequate human development. Prominent economic development scholar Jeffrey Sachs notes poverty is a contributing factor to corruption17 and the MENA region is no exception. In a similar vein, low salaries of civil servants, a cause of corruption in emerging markets has been identified by Salem as a root cause of corruption in MENA.18 |

Culture |

A culture of “wasta” and bribery and corruption is endemic to the region.19 Wasta, which at its root meaning roughly translates to “middle,” describes the act of a mediation or go-between to influence decisions or bestow favor.20 This intercession is used to facilitate daily transactions in the life of most Arabs. Salem identifies the historical rule of the Ottoman administration for inculcating a culture of corruption of the civil service in the Arab world.21 Furthermore, the region is diverse economically, politically, ethnically, and religiously which creates factionalsim in society that often gives way to sectarian and religious strife characterizing the region.22 This sectarianism helps a culture of corruption to thrive as civil servants are more apt to help their family or clan than to feel obliged by national identity to serve everyone equally under the law. |

Business and The Business of Corruption

Business is implicated in the fight against corruption, as it sometimes plays a role in catalyzing corruption and also suffers from its consequences. Business acts on the supply side of public–private corruption in numerous ways, and economists and development specialists alike have been keen to show the severe socioeconomic side effects of such involvement. In the sections below, we provide evidence that corruption significantly increases the cost of doing business, but also has detrimental effects at the level of society at large, which come back to haunt a business in its basic operations.

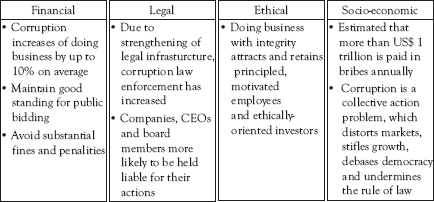

Starting with the negative externalities that corruption has on business itself, the World Economic Forum (WEF) has created a platform for business to address corruption in an initiative known as Partnering against Corruption Initiative (PACI). In mobilizing the business community in the anti-corruption platform, PACI has put together a business case against corruption. Using the simple and practical language of business, the PACI business case against corruption makes the platform for business to combat corruption easily accessible to any manager or director. See Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1. PACI business case against corruption.24

Figure 4.1 provides a sense that corruption raises the cost of doing business both in time and money and therefore decreases profitability. In a report to the World Bank in 1997, Rose-Ackerman offers two pieces of advice regarding the debate about corruption “greasing or sanding” the wheel of economic development.23 She states emphatically that corruption is always a second best option. While it may grease the wheel, its negative externalities will eventually outweigh the grease it can provide and start “sanding” the wheel. Corruption is not a sustainable strategy. When businesses engage in corruption, there are serious financial costs, as well as costs in terms of time and productivity. Moreover, with enhanced legislation and enforcement, the cost of getting caught looms large.

At the societal level, there is little doubt and accumulating evidence that the negative externalities of corruption far outweigh its potential greasing effect in the short term. Corruption has indeed been shown to negatively affect the following indicators:

•Economic growth: Aggregate levels of economic growth are negatively affected by corruption because it decreases efficiency of the marketplace and inhibits or detracts investment activity and acts as a barrier to trade.25 In parallel with slowed growth comes lower GDP per capita.

•GDP per capita studies that show a negative correlation to corruption.26 It is relevant to note that despite the overwhelming evidence that corruption negatively affects growth, the Asian Tigers of Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Korea have been outliers to this evidence.27

•Biased composition of government expenditures: Mauro produced for the first time quantitative empirical evidence that corruption diverts government spending away from issues of national importance, such as health care or education.28 In his particular study, he proved that for every one standard deviation point of additional corruption, GDP spending per capita on education was reduced by 0.05%.

•Political stability, including undermining trust in public institutions and legitimacy.29 This concept is pronounced in the Arab Spring context, where highly corrupt countries such as Libya, Syria, Bahrain, Egypt, and Tunisia have witnessed extreme political instability as a result of people demanding less corruption, more transparency and more freedom. The Arab context will be given more attention in the following sections.

Given the findings above, it is apparent that there is a viable business case to be made for anti-corruption; moreover, it becomes a business imperative to fight corruption. This implicates business in the fight against corruption, first for its own sake, and secondly, as an avenue for open and transparent society-building and sustainable development. Many businesses have taken heed of this information and started recreating policies and procedures to combat corruption. Many have introduced these changes within an agenda of corporate social responsibility (CSR). A 2005 survey by the University of Hong Kong compiled a list of the most salient CSR priorities for business and their stakeholders.30 Telling results ranked corruption as a top priority in a survey of over 15 issues. Addressing anti-corruption should therefore be integrated within the CSR and strategy framework of business firms globally. While business is starting to realize the business case for transparency and fair practice, it is imperative that business schools also start to integrate these relevant and important topics into their curricula. The following section tackles in turn the role of business schools in the fight against corruption.

Business Schools in The Fight Against Corruption

Do business schools have a role to play in addressing corruption? Illustrative and compelling empirical, as well as contemporary anecdotal evidence show that corruption is a tremendous societal problem with huge economic and political costs, as well as a salient business issue. Why then are business schools not addressing this issue more explicitly? Education gets to the root cause of many of these corrupt behaviors and offers hope and potential to address the inception of the problem, rather than law enforcement or compliance programs. Raging debates about the role of business schools in nurturing integrity and fighting corruption continue to unfold with the main axes of the controversy summarized as follows: (1) To teach or not to teach business ethics; (2) If one is convinced of the argument that business integrity should be taught then there are further debates in which to engage regarding teaching business ethics in the classroom: (A) Should it be taught as a stand-alone course, or should it be integrated into all courses? (B) Should the methodology of focus be on ethics or compliance?

The first argument is that “you can’t teach ethics, so you should not even try.” There are many arguments on this side of the debate. They can be summarized as such: First, the “Milton Friedman” argument, which posits that the private sector is only obligated to engage in activities geared toward profit maximization. If one uses this argument, it typically implies that students should only study what increases their technical prowess, and in this case, ethics courses would be a waste of time. The second argument relates to incentives and states that even if there are duties beyond profit maximization, the only practical way to encourage ethical behavior is through appropriate incentives, because business people usually respond to these, not ethics lectures. In this case, it isn’t necessary to teach ethics, but simply to teach compliance. The third argument pertains to moral development, pointing out that ethical behavior is related to personal moral development, which is not easily molded in a classroom setting.

On the other side of the teaching ethics debate, Von Weltzien Høivik argues that despite the fact that teaching ethics is admittedly difficult, we have also learned through research that a course about ethics in a business school can be effective in developing moral awareness and reasoning.31 Moreover, the business community itself has given a compelling call to action for business schools. In a 2010 UN Global Compact survey of over 750 CEOs, 88% of CEOs surveyed said that they believe it is important that educational systems in general and business schools in specific equip future leaders with the mindsets and skills needed to manage sustainability.32 If anti-corruption can be viewed in the context of a sustainability framework then it seems a pressing business imperative that students learn about corruption as a sustainability issue in the classroom.

Regarding the debate about how to institutionalize ethics in the curriculum, the first position argues for a stand-alone course to be made mandatory for students and the second position argues for integration. This controversy came to light in 2002 when AACSB stated that mandatory ethics courses would not be required for accreditation. Many professors were furious, recognizing that AACSB failed to enact a policy about teaching ethics that could have had a substantial impact on student education. Recognizing that AACSB has considerable impact on the curricular decisions of thousands of universities across the globe, Windsor and Swanson drafted a letter to AACSB in 2002, which was signed by over 200 professors, making the case for the importance of stand-alone ethics courses. They conclude their argument for the importance of stand-alone ethics course mandated by AACSB Accreditation by saying, “Although one ethics course won’t solve all ills, it could be the only opportunity some students have to grasp a saner view. It might also keep some of them out of jail.”33 It is this strategic concept that we believe should drive education about corruption especially given that AACSB Accreditation is being widely sought after in the MENA region.

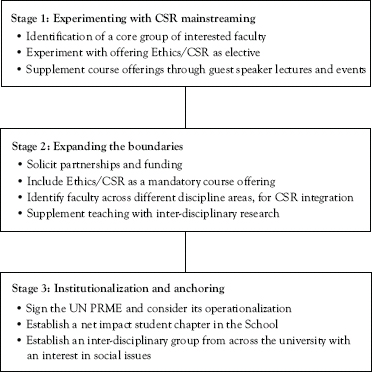

Whatever side of the debate one finds most compelling, the practical challenge of implementation and institutionalization within the business school context looms large for most sustainability advocates. Jamali and Abdallah provide a useful framework to use in institutionalizing corporate responsibility teaching and practice within a business school context.34 They refer to this process as “mainstreaming CSR” and provide a helpful roadmap for business schools looking to implement a sustainability approach. This roadmap will be a useful tool for designing appropriately paced recommendations for MENA business schools looking to institutionalize anti-corruption teaching. The three-step framework is illustrated in Figure 4.2 and sample activities are provided within each stage of the model.

Figure 4.2. A typical CSR mainstreaming process.35

MENA Business Schools in The Fight Against Corruption

Given the significance of corruption, the systemic nature of its causes in the MENA, and the business case to be made for anti-corruption, businesses in the MENA have begun to take a stand. There are over 250 companies in the MENA region that are active signatories to the UN Global Compact, which includes a principle to combat corruption.36 “The United Nations Global Compact is a strategic policy initiative for businesses that are committed to aligning their operations and strategies with ten universally accepted principles in the areas of human rights, labor, environment and anti-corruption.” Since its official launch in 2000, the initiative has grown to more than 8,000 participants, including over 6,000 businesses in 135 countries around the world.

Regional business schools are also starting to understand the importance of teaching business transparency. In a recent survey of MENA business schools, we garnered the following results.37 The objective of the data compilation and analysis was to generate a report on what schools in MENA were teaching regarding the subject of corruption. The methodology undertaken for the secondary data collection was to use publically available information on the Internet to find out if and how MENA business schools are addressing the subject of integrity and anti-corruption in their curricula. Whenever possible, personal contact with schools was made directly, via email or a telephone call. Business school websites were used to get information about faculty and curricula. When the curriculum was not posted online, data was then compiled from email exchange, and the use of a questionnaire (Appendix A).

The first phase of the methodology was to compile a sample of schools. A list of business schools in the MENA was derived from Eduniversal, a French-based consulting company and a rating agency specializing in higher education. The Eduniversal ranking agency establishes an official selection of the Best 1000 Business Schools in more than 150 countries in the world, annually. Schools get rated and ranked in the Eduniversal study. We took the ratings for each school in our sample and marked them qualitatively as per Eduniversal’s codes: Local Reference (1), Good Business School (2), Excellent Business School (3), Top Business School (4), Universal Business School (5). None of the schools in the Arab MENA were ranked in the 5th category. Only two were given a number 4 ranking, as “top business schools.” The sample attempted to take at least one university from each of the 21 countries in the study. The only countries not represented in the sample are Libya and the Comoros Islands. University of Baghdad was used for Iraq, but not listed in the Eduniversal survey for 2011.

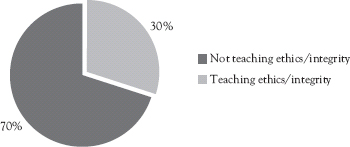

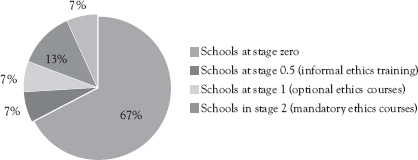

To analyze the responses from the website searches, questionnaires, and email conversations, Microsoft Excel was used. We first listed all the schools and then noted their country, their Eduniversal score, whether or not business ethics was taught, whether it was integrated or stand-alone, and made any additional notes given. We then sorted these responses with the data sort function in excel to tally the number of schools per sample that taught business ethics. Nine schools out of the 30 in the sample, or 30% of the sample teach some form of business integrity coursework. We then further classified those 10 programs accordingly to the Jamali/Abadallah (2011) “Mainstreaming CSR” framework and identified, based on the framework, what stage of mainstreaming each program was in. See Appendix B.

•Number of Schools in Eduniveral study, 2011: 48

•Number of Schools in Sample: n = 30, 63% of Eduniversal survey

•MENA Countries Represented: 20/22, 90% of Arab States

•Questionnaires Sent: 23/30, 76% of sample

•Questionnaires Completed: 6/23, 26% response rate

•Information taken exclusively from website: 18/30, 60% of sample

Figure 4.3. MENA schools teaching business ethics.

Figure 4.4. Mainstreaming stages of anti-corruption teaching.

Below are the aggregate results of the schools in the sample.

•30% of schools surveyed were teaching ethics or corporate governance in some manner, either integrated or stand-alone

•44% of schools teaching ethics responded that the curriculum deals directly with teaching anti-corruption

•Number of faculty teaching ethics and currently engaged in the teaching of business ethics from this survey equates to less than 1 per MENA country

•Only one school in the sample is a signatory to the UN PRME (American University of Cairo)

Recommendations—A Business Ethics Pedagogy to Address MENA Corruption

The following section outlines recommendations for MENA business schools to implement curricula that adequately address the topic of corruption. These recommendations are synthesized from the business case against corruption, global best practices in teaching integrity and ethics in business schools, and account for the peculiar characteristics of corruption in MENA. We make a number of relevant suggestions that are likely to be useful for business schools around the globe in terms of tailoring their curricula to buttress the fight against corruption. These include: (1) mandatory exposure to business ethics; (2) mandatory exposure to compliance frameworks; (3) contextual and experiential learning about anti-corruption; (4) gradual mainstreaming of ethics, CSR and anti-corruption offerings, and (5) a five P framework of teaching anti-corruption in MENA: “Pilot, Partner, Practice, Promote, PRME,” synthesized at the end of this table.

Conclusion

This chapter compiles the literature on corruption that is specific to the MENA region and specific to the private sector to attempt to construct a relevant, high-impact pedagogy for teaching business ethics in MENA classrooms. This effort is both timely and relevant. The time is ripe in the Arab states to introduce change. From Egypt to Bahrain, citizens are demanding and expecting change. The region is dynamic in a way not seen for decades. Free and fair elections are being held and the people for the first time in years are choosing their representatives. Now is the right moment to introduce a new paradigm of business ethics, integrity, and anti-corruption education to the region. People want democracy in government and transparency in the private sector as well. As indicated by the Corruption Perceptions Index scores from Transparency International, the region stands to improve the transparency with which it operates, both within the private and public spheres. If the private sector seeks to act strategically, it will harness the current zeitgeist sweeping across the region and build on existing anti-corruption platforms in the region. Moreover, business schools should join this movement and introduce more ethical leadership in the classroom to educate the next generation of business leaders that can further an anti-corruption agenda. They can do this in a way that specifically addresses the contemporary needs of business and the needs of the MENA at the same time in an effort to be powerful agents of change in a region that is brimming with the seeds of transformation and revolution.

Recommendation |

Justification/Actionable steps |

|---|---|

1. Mandatory exposure to business ethics |

Teaching integrity and anti-corruption is an imperative for business schools across the globe. Business professionals wield a tremendous amount of power, both to generate positive and negative externalities from their work. When business professionals act without integrity, they can cause significant harm to society and the environment.38 Moreover, it is especially critical to teach business students about integrity, as they have been shown in numerous studies to be on average less concerned about ethical decision-making than their peers in other disciplines, and more motivated by financial gain.39 Finally, if business schools want to remain relevant and competitive, they must train students on these contemporary, business-critical issues. |

2. Mandatory exposure to compliance frameworks |

Compliance frameworks are necessary to teach because trends in global business indicate a need for business leaders to think about issues of sustainability.40 As demonstrated, corruption is a business compliance issue that can have serious legal and financial consequences. An anti-corruption agenda should be fully realized in the classroom as strategic business issue. This can be achieved by teaching it in line with strategic corporate governance, Strategic CSR or as a stand-alone course. Placing these topics inside a strategic management or in a stand-alone course gives them attention to pertinent business trends in CSR and anti-corruption, which are gaining momentum in institutional practice and in enforcement. |

3. Contextual and experiential learning about anti-corruption |

Instructors of ethics and integrity in MENA business schools should be concerned with contextualizing anti-corruption to the region, as corruption has its own peculiarities in the MENA. Currently, many of the resources that are used to teach anti-corruption in the classroom come from a Western context, where manifestations and prevalence of corruption are different than in the MENA. It was noted in 30% of the completed questionnaires to MENA business schools that relevant, regional, contextual material needs to be developed for the region. The literature on teaching business ethics is full of examples of the power of exposure to ethical issues via experiential models.41 Regarding experiential learning, Sanyal reminds the reader of a popular quote attributed to Confucius, “I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.” This quote has been referenced numerous times to explain why it is that students respond better when they are actively engaged in the learning. Studies show that experiential learning helps students retain the material longer and participate more actively in the learning process.42 |

4. Gradual mainstreaming |

For the majority of MENA business schools that find themselves in Stage 0 or 0.5 of sustainability mainstreaming, placing anti-corruption curriculum inside the context of strategic management courses, which are required in all BBA and MBA curriculum, gives the subject required “air-time,” without having to introduce new courses. To address anti-corruption in an academically rigorous manner using this framework, professors can use literature regarding strategic CSR.43 Additional tools that can be useful are the business cases that have been made for anti-corruption such as the WEF PACI, the World Bank, and the United Nations. The Journal of Teaching Business Ethics is another great resource for instructors to use in forming relevant pedagogy and learning best practices. Since 2004, it has published over 24 articles that deal explicitly with teaching anti-corruption in the business school setting. For schools in Stage 1 and moving to Stage 2, a more rigorous pedagogy is recommended. Below are concrete examples of how schools can implement such curriculum. We refer to these recommendations as the five P’s of teaching anti-corruption in MENA, “Pilot, Partner, Practice, Promote, PRME.” |

5. The Five P’s |

Pilot Innovative Approaches and A Reality-Based Curriculum: Case studies on corruption are plentiful and are a great starting point for trying to bring reality into the classroom. In addition to case studies, numerous anti-corruption resources can also be found from institutions such as: Ethical Corporation, Transparency International, Center for Private Enterprise (CIPE), World Economic Forum, United Nations, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Partner with Regional Business Leaders and Anti-Corruption Specialists: Partnerships offer the opportunity for both experiential and contextual learning that is integrative in framework and approach. There are over 250 businesses and organizations that are UN Global Compact signatories in the MENA with which schools could partner. Practice Transparency and Anti-Corruption: It is important that students see these behaviors modeled and applied. The university settings should be modeling the way forward both in practicing and teaching transparency methodologies. If the business school is encased in a larger university structure, it can act as an advisor to the university about sustainability practices, transparency, and anti-corruption. |

Promote Scholarship in Corruption: Business ethics as a scholarly field depends critically on the research of its leading scholars. If business schools make a commitment to teach business ethics, they must also accept an obligation to support scholarship in the field. As was mentioned in the notes of 30% of the completed questionnaires relevant, regional, contextual material needs to be developed for the region. Join the UN PRME Network: The value proposition for schools joining UN PRME is that it provides a framework for business schools to position themselves as innovators in integrating sustainability into management curricula and research. It also recognizes an organization’s efforts to incorporate sustainability and corporate responsibility issues in teaching, research, and internal systems. |

Key Terms and Definitions

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The commitment of business to managing and improving the economic, environmental, and social implications of its activities at the firm, local, regional, and global levels. (World Bank)

Corruption Perception Index (CPI): The CPI ranks countries/territories based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be. It is a composite index, a combination of polls, drawing on corruption-related data collected by a variety of reputable institutions. The CPI reflects the views of observers from around the world, including experts living and working in the countries/territories evaluated. (Transparency International).

Rentier state: A state as one that extracts a significant share of its revenues from rents extracted from international transactions, such as oil/mineral extraction, tourism, remittances, etc.

Wasta: At its root meaning roughly translates to “middle,” wasta describes the act of a mediation or go-between to influence decisions or bestow favor.44

Study Questions

1.How is corruption manifest in the Middle East?

2.What are its root causes?

3.Are business ethics courses in the region addressing these issues? If so, how?

4.What does the author recommend for the region?

5.Given the authors’ recommendations and the practical application tools from the other chapters in the book, if you were to be a consultant for a MENA business school, what steps would you recommend the business ethics curriculum take to combat regional corruption?

Additional Reading

Arab Human Development Report (2009). Challenges to human security in the Arab countries. New York: United Nations Publications.

Beblawi, H. (1990). The rentier state in the Arab world. In Luciano, G. (Ed.), The Arab state (pp. 85–94). London: Routlege.

Doh, J., Rodriguez, P., Uhlenbruck, K., Collins, J., & Eden, L. (2003). Coping with corruption in foreign markets. Academy of Management Executive, 17(3), 114–127.

El-Din Haseeb, K. (2011). On the Arab “democratic spring”: Lessons derived. Contemporary Arab Affairs, 4(2), 113–122.

El Badawi, I., & Makdisi, S. (2011). Democracy in the Arab world: Explaining the deficit. London: Routledge.

Hills, G., Fiske, L., & Mahmoud, A. (2009). Anti-Corruption as Strategic CSR: A Call to Action for Corporations. FSG Social Impact Advisors. http://www.fsg-impact.org/ideas/item/Anti-Corruption_as_Strategic_CSR.html

Hooker, J. (2004). The case against business ethics education: A study in bad arguments. Journal of Business Ethics Education 1(1), 73–86.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Appendix A: Arab States: Summary Statistics, 2011

Country |

Population estimates 201245 |

Percentage of Arab world by population |

GDP in USD 201146 |

HDI rank 201147 |

TI CPI rank 2011 |

Polity IV score |

Freedom in the world |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Algeria |

35,400,000 |

11.16% |

7,200 |

96 |

112 |

2 |

Not free |

Bahrain |

1,240,000 |

0.39% |

27,300 |

42 |

46 |

8 |

Not free |

Comoros |

737,000 |

0.23% |

1,200 |

163 |

143 |

9 |

Partly free |

Djibouti |

774,000 |

0.24% |

2,600 |

165 |

100 |

2 |

Not free |

Egypt |

83,600,000 |

26.35% |

6,500 |

113 |

112 |

3 |

Not free |

Iraq |

31,100,000 |

9.80% |

3,900 |

132 |

175 |

3 |

Not free |

Palestine |

4,200,000 |

1.32% |

5,84848 |

114 |

36 |

Not given |

Not free |

Jordan |

6,500,000 |

2.05% |

5,900 |

95 |

56 |

3 |

Not Free |

Kuwait |

2,600,000 |

0.82% |

40,700 |

63 |

54 |

7 |

Partly free |

Lebanon |

4,100,000 |

1.29% |

15,600 |

71 |

134 |

7 |

Partly free |

Libya |

6,700,000 |

2.11% |

14,100 |

64 |

168 |

7 |

Not free |

Mauritania |

3,350,000 |

1.06% |

2,200 |

159 |

143 |

2 |

Not free |

Morocco |

32,300,000 |

10.18% |

5,100 |

130 |

80 |

6 |

Partly Free |

Oman |

3,000,000 |

0.95% |

26,200 |

89 |

50 |

8 |

Not free |

Qatar |

1,950,000 |

0.61% |

102,700 |

37 |

22 |

10 |

Not free |

Saudi Arabia |

26,500,000 |

8.35% |

24,000 |

56 |

57 |

10 |

Not free |

Somalia |

10,000,000 |

3.15% |

600 |

Not given |

Not given |

7749 |

Not free |

Sudan |

26,000,00050 |

8.20% |

3,000 |

169 |

177 |

2 |

Not free |

Syria |

22,500,000 |

7.09% |

5,100 |

119 |

129 |

7 |

Not free |

Tunisia |

10,700,000 |

3.37% |

9,500 |

94 |

73 |

4 |

Partly free |

UAE |

5,300,000 |

1.67% |

48,500 |

30 |

28 |

8 |

Not free |

Yemen |

24,700,000 |

7.79% |

2,500 |

154 |

164 |

2 |

Not free |

Appendix B: Summary of Research Findings

Business school |

Country |

Ranking per Eduniversal 2011 |

Main-streaming stage |

|---|---|---|---|

American University of Beirut: Suliman S. Olayan School of Business (OSB) |

Lebanon |

Top business school |

Stage 3 |

The American University in Cairo: School of Business |

Egypt |

Top business school |

Stage 3 |

Kuwait University: College of Business Administration (CBA) |

Kuwait |

Excellent |

Stage 2 |

University of Dubai: College of Business Administration |

UAE |

Excellent |

Stage 1 |

King Saud University: College of Business Administration |

Saudi Arabia |

Good |

Stage 1 |

Qatar University: College of Business and Economics |

Qatar |

Good |

Stage 1 |

Sultan Qaboos University: College of Commerce and Economics |

Oman |

Good |

Stage 1 |

United Arab Emirates University (UAEU): College of Business and Economics |

UAE |

Excellent |

Stage 0.5 |

Ecole Supérieure des Affaires |

Lebanon |

Good |

Stage 0.5 |

Queen Arwa University: College of Commercial Sciences and Administration |

Yemen |

Local reference |

Stage 0 |

ESSEC Tunis |

Tunisia |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

IHEC Carthage |

Tunisia |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

Institut Supérieur de Gestion de Tunis (ISG) |

Tunisia |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

HIBA:Higher Institute of Business Administration |

Syria |

Good |

Stage 0 |

University of Khartoum:School of Management Studies |

Sudan |

Local reference |

Stage 0 |

Mogadishu University: Faculty of Economics & Management Sciences |

Somalia |

Local reference |

Stage 0 |

CBA: College of Business Administration |

Saudi Arabia |

Good |

Stage 0 |

King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals: College of Industrial Management |

Saudi Arabia |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

Al-Quds University: Faculty of Business & Economics |

Palestine |

Local reference |

Stage 0 |

Groupe ISCAE |

Morroco |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

HEM: Institut des Hautes Etudes de Management |

Morroco |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

Université de Nouakchott: Faculté des Sciences Juridiques et Economiques (FSJE) |

Mauritania |

Local reference |

Stage 0 |

Universite Saint Joseph |

Lebanon |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

The University of Jordan: Faculty of Business |

Jordan |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

University of Baghdad |

Iraq |

Not listed |

Stage 0 |

Ain Shams University: Faculty of Commerce |

Egypt |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

Université de Djibouti: Faculté de Droit Economie Gestion (FDEG) |

Djibouti |

Local reference |

Stage 0 |

University College of Bahrain (UCB): School of Business |

Bahrain |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

Ecole Supérieure des Affaires d’Alger (ESAA) |

Algeria |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |

MDI Alger Business School |

Algeria |

Excellent |

Stage 0 |