CHAPTER 8

The Cultural Dimensions of Corruption: Integrating National Cultural Differences in the Teaching of Anti-Corruption in Public Service Management Sector

Abstract

Teaching and training for good governance and culturally effective anti-corruption practices require a multilevel approach. Based on numerous empirical and theoretical studies on the causes, nature, and correlations of corruption across countries, this study introduces an integrated approach to teach and train on anti-corruption. Building on institutional theory, principal–agent theory and cultural dimension theory the author suggests a multi-level and multi-cultural anti-corruption model. Through the examination of selected cultural dimensions in relation to corruption, the chapter suggests an integrated model for teaching anti-corruption in the public service management sector.

Keywords

bribery clientelism, collusion, cronyism, corruption, cultural dimensions, nepotism

Introduction

Anti-corruption teaching and training in the public service management sector centers on the understanding and practices of good governance.1 Hence, the prevention of corruption—the misuse of public office for private gain—begins with the right ethical education of public servants. Integrity, accountability, and transparency are the main subjects explaining good governance to public servants and government administrators.2 However, in spite of the mounting evidence of empirically measured correlations between cultural values and corruption perceptions, the study of cultural competencies and anti-corruption practices in public service education remains a marginal topic. A growing number of training manuals and textbooks promote anti-corruption practices by focusing on personal integrity coped by new economics of organizations based on financial and institutional mechanisms for accountability and transparency.3 Indeed, anti-corruption requires cross-sector and multidimensional approaches integrating the shared responsibility of individuals, organizations, and institutions in the public sector, private sector, and the third sector. However, all these efforts and strategies to fight corruption would be ineffective without understanding cultural values and the influence that cultural dimensions have on the perception and practice of corruption.4

This chapter attempts to answer three questions on the relation of corruption and culture and on the teaching of anti-corruption practices to public service students:

•Teaching anti-corruption: How can we teach anti-corruption with its complex, multicultural and multifaceted nature?

•International differences: Why is corruption perceived to be more widespread in some countries than others?

•Culture and corruption: What is the influence of national cultures in the perception and practices of corruption?

We do so by exposing the main characteristics of corruption in relation to selected cultural dimensions and based on the author’s teaching and training practices on public service global ethics. These questions on corruption and concerns on the relation of this phenomenon to culture and capacity building for good governance are frequent in academic studies along with world development and policy reports. Corruption can no longer be seen as an isolated unethical behavior of individual public servants without considering the effect of insufficient or inadequate rule of law and government control mechanisms. The assumption of this study is that public service students need to understand corruption in relation to systems (institutional analysis) and culture (cultural dimensions). Therefore, the author presents this examination of corruption in its definition, cultural aspects, and practical applications as emerging from effective teaching practices with American and international students. A review of empirical and theoretical studies of corruption across cultures is necessary as our students begin their careers and our societies increasingly become more international and inter-culturally related. Hence, effective teaching of anti-corruption and good governance requires intercultural learning and cultural competency.

Corruption is not just an ethical issue and its consequences go far beyond the criminal actions of an unethical person. Individual actions are linked to institutional actions (or lack of them) allowing, tolerating, and sometimes promoting small-or large-scale corrupt practices. Empirical research on corruption has convincingly shown that poor governance, typically in various forms of corruption, is “a major deterrent to investment and economic growth and has had a disproportionate impact on the poor.”5 Poor governance and corruption perpetuate poverty and inhibit common good economics and foreign investments benefiting the creation of sustainable development projects. We also know that corruption is not the sole responsibility of public officials but also of civil society and business sector. Therefore, effective anti-corruption strategies need to have comprehensive multi-sector integrated approaches. A key element of this is the ethical education of public servants. Master programs in public administration, public service, and international development should include in their curricula both theoretical and practical insights on good governance and anti-corruption. The effectiveness of such educational insights depends on international and intercultural competency. It depends also on the curricula articulation of theoretical understanding and practical applications of the complex phenomena of corruption. Effective good governance and anti-corruption teaching would also require being both culturally intelligent and internationally competent, addressing the interpersonal, inter-organization, inter-institutional and intercultural facets of corruption.

This chapter addresses the importance of teaching anti-corruption to public service students with an integrated approach. First, we need to understand what we mean by corruption and how the typology of corruption differs in the interpretation across cultures, sectors, and national societies. Second, we need to examine the causes of corruption in relation to the cultures of the agent, client, and agency. Third, we will consider some theoretical explanations on the influence that national cultures have in the perception and practice of corruption. Fourth, based on the empirical and seminal studies of national cultural dimensions, we will exemplify how power distance, individualism, collectivism, and other cultural values relate to corruption. Finally, we will propose an integrated model for teaching anti-corruption while fostering sustainable and intercultural good government solutions. We offer this analysis of corruption and cultures in the hope that public service managers, students, and instructors would gain better understanding on how culture impacts the perception and practices of public sector corruption.

Understanding the Nature of Corruption

Corruption has diverse interpretations across diverse cultures. What is perceived as “bad,” “unethical,” and/or illegal behavior in one culture may be regarded as a normal and expected “good” practice in another cultural context.6 Diversity of values across cultural diversity is not the only issue in detecting corruption. Often corruption is simply stated as “illegal” or “unethical” but without a proper definition or classification. The teaching of anti-corruption for the public service management sector must begin with the proper understanding of this complex phenomenon. Transparency International defines corruption as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.”7 Similarly, the World Bank defines corruption as “the misuse of public office for private gain.”8 Unfortunately, these commonly used definitions of corruption do not reflect the complexity of the phenomenon and, without proper explanations, risk to err on the side of oversimplification. It is therefore fundamental to ask the question of what constitutes corruption in its typology and across national cultures. Even in those societies where corruption has a thorough legal designation, certain actions (e.g., lobbying) may be perceived by other cultures as corruption. This means that seeking a more international understanding of the nature of corruption requires an analysis on typologies of corruption across sectors, public functions, and national cultures.

Corruption is present in every sector, society, and affects everyone. We cannot adequately prevent corruption of the public sector without the co-responsibilities of other sectors and stakeholders. Corruption appears to hurt everyone and every sector that depends on the integrity of people in a position of authority. In government, corruption is manifested when private interests are placed ahead of the public good, steering away scarce resources from poor and disadvantaged people. In the private sector, bribery practices distort markets and create unfair competition. Corruption is even present in the nonprofit sector with corrupt charities, fraudulent reporting, and frequently undisclosed conflict of interests. The concept of corruption itself is quite broad and covers a wide range of phenomena. Some of the most common distinctions in corruption typologies are between grant and petty corruption and between episodic and systemic corruption.9 Petty corruption covers everyday corruption that takes place at the implementation end of policies, where public officials interact with the public. Petty corruption is bribery in connection with the implementation of existing laws, rules, and regulations. Petty corruption often turns out to be anything but petty. It could be quite prevalent in certain contexts where demanding “speed money” to issue licenses to access to schools, hospitals, or public utilities is the norm. When it tends to affect the daily lives of a very large number of people, especially poor, it creates a “culture of corruption.”10 Corruption perpetuates and prospers in contexts characterized by lack of accountability/transparency and a sustained culture of silence. Transparency in government affairs can also overcome the culture of secrecy within bureaucracies to expose the administrative processes to greater public scrutiny.

Public corruption generally refers to public servant officials accepting, soliciting, or extorting a bribe. However, corruption affects every sector and it may mean different kinds of unethical and/or criminal actions. Corruption of public officials can mean not only financial gain but also nonfinancial advantages as in the cases of nepotism, patronage, theft of state assets, and the diversion of state revenues. There are many other forms of corruption and practices often identified between the lines of crime, unethical behavior, and cultural practices. These include favoritism, perks, money laundering, rent seeking, and state capture as a legal way of legalizing corruption. Although studying the complex typology of corruption could be distracting, the reference to these many faces of corruption are important in understanding the complexity and variations of the phenomenon across sectors, societies, and cultures.

Corruption does not happen as an isolated phenomenon. It is a global challenge interlinked to other international threats to our global societies such as human trafficking, illegal trade, and organized crime. Public corruption impacts human development, international cooperation, and the individuals who are targeted to receive humanitarian assistance or poverty reduction assistance. As Transparency International observes, “one cannot protect democratic freedoms and human rights without addressing corruption. And one cannot end corruption without working towards democratic accountability and respect for human rights.”11

The Cultural Causes of Corruption

There are many causes of corruption in public service. Most empirical and theoretical studies of corruption identify the historical and cultural traditions of a country along its level of economic development. The governance capacities of political institutions are critical factors.12 Culture is generally recognized to be an important macro variable that influences the perception and practices of corruption.13 Far from being a mechanical result, the causal explanation of this complex phenomenon has been described with a simple formula: C=R+D-A meaning that corruption is the result of the level of economic rent (R), defined as something valuable to offer, plus the degree of discretion powers (D), and minus the level of accountability (A).14 This means that (i) corruption is most likely to occur when valuable assets are at stake, numerous restrictive measures, rules, regulations, and administrative orders are too complex or too restrictive; (ii) Corruption is likely to appear when administrators are granted a large degree of discretionary powers in interpreting the rules; (iii) Corruption will most likely happen when the above conditions are accompanied by a lack of effective mechanisms to hold administrators accountable.

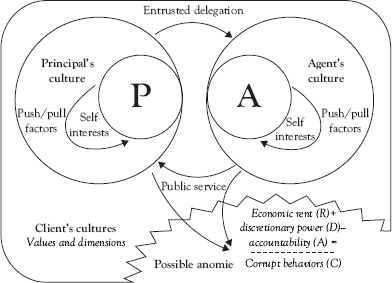

The principal–agent model is often used to explain how corruption occurs.15 Within the interactions between the principal (the government) that employs the agent (administrator, public servant) and the client (interest groups), corruption occurs under conditions of incomplete and asymmetric information between the principal and the agent. Because the principal is hiring the agent to pursue the principal’s interests, potential moral hazard and conflict of interest often occur. The corrupt exchanges pervade when the agent encourages private gain in the making of public decisions. To be noted is that the principal–agent problem with such asymmetric dissociations is not limited to bureaucratic corruption.16

Culture interacts with the principal–agent dynamics as illustrated in Figure 8.1. The principal and the agent may have a shared national culture with a set of values and dimensions. However, their decision-making and performance for the public (client) may be aligned or not depending also on the push–pull influence of inner cultural values. The client’s culture may refer to a national culture or other collective identities. Cultural values influence decision-making in public service or corrupt behaviors. These dances of push and pull factors affect individual or corporate self-interests by legitimizing certain actions and discouraging others. When dissonances in the public service contract occur, conflict of interests and possible anomie emerge at personal, organizational, or institutional levels. When cultural values collide in a context dominated by high level of economic rent, a large degree of discretion power and a low level of accountability, corruption is likely to occur.

Figure 8.1. principal–agent model for corruption and culture.

In their institutional analysis of the relationship between corruption and cultures, Soma Pillay and Nirmala Dorasamy argue that corruption is a multidimensional phenomenon. Following other studies in political corruption, they propose two fundamental dimensions of corruption: pervasiveness and arbitrariness.17 They explain pervasiveness as “the degree to which corruption is prevalent in a given country” and arbitrariness as “the inherent degree of ambiguity associated with corrupt transactions in a given nation or state.”18 Their framework of analysis proposes that variations in accountability and discretion can explain variations in the pervasiveness and arbitrariness of corruption in different societies. These dimensions of corruption interrelate with their social and cultural contexts through the institutions and values that shape actions and influence decision-making. Social institutions and national cultures are therefore central to understand the dynamics of corruption.

Cultural Theory and Corruption Practices

Fighting corruption in public officials requires more than a strict policy regarding conflict of interest. Culture matters in the perception and practices of public sector’s corruption. We need to consider how diverse cultural values affect expectations and perceptions of behaviors. Numerous studies have shown that the practices and causes of corruption are correlated to cultural values.19 Although diverse national cultural dimensions have an effect on corruption, the institutionalization processes associated with globalization and location can strive to find a shared set of core values, particularly around integrity, transparency, and accountability. While corruption is a concept emerging from Western culture, any society understands the difference between practices that are acceptable and those that cause outrage. Every culture has a sense of right and wrong and has their own notions of corruption. However, defining what constitutes corruption is to some extent arbitrary and culturally constructed. For example, the giving of gifts is an important ritual in many cultures and the discernment of what may constitute a bribe difficult. Some would consider even tipping a form of bribe.20

Building on the various empirical studies demonstrating the influence of culture on corruption, we suggest an integrated model that begins with a value-based notion of culture. This examination of national cultural dimensions is primarily based on Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory.21 In the latest evolution of his model, Geert Hofstede, with Gert Jan Hofstede and Michael Minkov, endorse six national dimensions as cultural values in relation to:

1. Power as equality versus inequality

2. Collectivism versus individualism

3. Uncertainty avoidance versus tolerance

4. Masculinity versus femininity

5. Temporal orientation versus long-term

6. Indulgence versus restraint

He identified national cultural diversity by measuring the variances of 93 national cultures across these six dimensions.22 His well-known computer analogy explains culture as “collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others.”23 Most people in the same culture carry the same values, with a value being defined as “a broad tendency to prefer certain states of affairs over others.”24 Values are therefore of essence to cultures and culturally driven choices. Cultural values are embedded in people’s attitudes and beliefs. Although many other studies on the classification of national cultures have emerged, Hofstede’s work remains the most widely accepted means of investigating a society’s culture.25

Robert House’s Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research Project (GLOBE) largely confirms the influence that cultural dimensions have on individual values and behaviors.26 The GLOBE study borrowed some and expanded other dimensions from earlier Hofstede’s studies examining a total of nine dimensions identified as power distance, uncertainty avoidance, humane orientation, collectivism I: (institutional), collectivism II: (in-group), assertiveness, gender egalitarianism, future orientation, and performance orientation.27 The emerged GLOBE’s implicit leadership theory is relevant to our discussion on the cultural influences on corruption. According to this theory individuals have implicit theories (beliefs, convictions, and assumptions) about the values, attributes, and behaviors of people in power. Hence, societal cultures legitimize or challenge leader’s behaviors based on their implicit cultural assumptions. Such implicit (non-conscious) values and assumptions affect an individual’s motives for social influence (achievement, affiliation, and power) and interact with structural factors (structural contingency). Building on GLOBE and Hofstede’s models, various empirical studies on the correlation of cultural dimensions with the perception of corruption clearly suggest the need to develop a general theory of the culture perspective of corruption.28

The relation and influence of culture to corruption has been studied from a variety of perspectives such as organizational theory, cultural theory, structural-functional theory, and political elasticity theory.29 While helpful to understand some functionalist (practical) and individualist (moral) aspects of corruption, they do not offer a sufficient explanation of corruption valiance and prevalence due to institutional capacity levels and national cultural dimensions. Empirical and experimental studies on the causes of corruption have identified national cultural variations of values in relation to the values and perceptions of corruption across nations.30 Culture is one of the macro level variables that influence the perception and practice of corruption across nations. Although it is quite difficult to measure corruption empirically, some scholars have been able to identify variables such as the economic development, legal system, openness to trade, and religious traditions, among others, to have statistical significance in the explanation of variance of corruption across nations, regions, and cultures.31 “Countries with Protestant traditions, histories of British rule, more developed economies, and (probably) higher imports were less ‘corrupt’.”32

Studies have also shown how corruption is correlated to economic, educational, public culture, organizational, judicial, and political measures.33 However, a very limited number of studies have been able to identify national and societal cultures as antecedent for corruption. Such adistinction is fundamental, as prescriptions for remedies on corruption may need different solutions and strategies across cultural variations. Any legal, economic, management, and accountability approach to fight corruption would require an attentive consideration of the underlying factors determined by cultural dimensions. Effective intervention in corrupt behaviors, similar to effective teaching and training methods on anticorruption, needs to have a comprehensive and multilayered approach. In other words, cultural dimensions need to be integrated as anteceding factors along macro level factors (economy, politics, legal, education, social systems) and micro level factors (pervasiveness, accountability, arbitrariness, and transparency).

The perspective of these seminal and comprehensive studies on national and societal cultural dimensions emerges from an institutional perspective. Subsequent studies have shown that the government corruption in relation to dynamics across nations is best explained by institutional theory.34 Therefore, before we examine the selected cultural dimensions in relation to national perception and practices of corruption we need to understand institutional theory. This is a fundamental step also in effective anti-corruption teaching and training. Institutional theory is particularly helpful to explain the deeper relation that culture has on corruption. We cannot dismiss the fact that some clear correlations exist between culture and corruption. However, to merely think that certain national cultures are prone to corrupt practices without considering other macro-and micro level factors is a simplistic explanation to a complex phenomenon.

Institutional theory is a helpful approach to explain individual actions, administrative performance, and institutional practices. In relation to corruption, institutional theory clearly resembles Durkheim’s sociological theory on “anomie.”35 Although anomie theory does not explain per se the relation and influence of culture in corrupt practices, it does offer a lucid explanation of the weakening of cultural values and societal norms. This phenomenon is often visible in societal rapid changes and it is characterized by deinstitutionalization of the preexisting normative control systems. The tension that societal changes create is often recognized as a duality between traditional normative and modernity expectations. Public service students and international development professionals alike need to be equipped with the capacity to understand corruption from an institutional anomie and cultural change standpoint. An integrated understanding of the nature of corruption requires an analysis of national macro cultural dimensions in relation to other macro-and micro level factors. Although no national culture is exempt from corruption, the variations on the perceptions and practices of corruptions across cultural lines requires a more careful consideration. It requires reviewing the value assumptions in cultures and how they affect institutional progress and institutional anomie.36

Cultural Dimensions of Corruption

For the purpose of this examination of the relation of culture and corruption we will concentrate on Hofstede’s original model with the four core national cultural dimensions known as power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity. Although these dimensions have been expanded from the original studies published in Culture’s Consequences (1980), and further elaborated in the GLOBE and subsequent studies, they remain the most widely accepted cultural dimensions. They have been subject of numerous analyses on their correlation with the corruption perception index (CPI) and other measures of corruption.37

Power Distance Index (PDI) and Corruption

Power distance is an important cultural dimension in the perceptions and practices of corruption in a particular country. A significant level of power distance in a country implies fewer checks and balances against power abuse and power is associated more with “privilege” than “responsibility.” Power distance is defined as “the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.”38 In relation to public service, PDI measures the degree to which members of a department or country expect and agree that power should be stratified and concentrated at higher levels of governance. The PDI is not an objective difference in power distribution, but the country average in the perception and degree of tolerance of unequal distribution and utilization of power.

In low power distance (low PDI) countries, people expect and accept power relations that are more consultative or democratic and they are related more informally with authority. Subordinates are more likely to challenge authority, demand their rights, and criticize the decision making of those in power. Low PDI societies expect and accept more equal power relations in more consultative and democratic practices. They will be more likely to monitor, critique, and challenge the decision making of institutions and people in power. The 10 third countries with the lowest PDI include Austria, Israel, Denmark, New Zealand, Switzerland (Ge), Ireland, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Great Britain, Germany, Canada, and the United States.39

In high power distance (high PDI) countries, people expect and accept power relations that are more autocratic and paternalistic. Subordinates are more likely to accept the power of others simply based on where they status and formal position. They acknowledge and respect the actions and decisions of institutions and people in power simply based on their subordinate position in the hierarchy of an organization or political structure of a country. The top third countries with the highest PDI include Malaysia, Slovakia, Guatemala, Panama, Philippines, Russia, Romania, Serbia, Suriname, Mexico, China, India, Singapore, and other Arabic and West African countries.40

Empirical studies testing the correlation between power distance (PDI) and corruption perceptions (CPI) show that high PDI societies result in more corruption cases.41 As in the famous aphorism “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupt absolutely.” Large power distance means fewer checks and balances on the use of power and the possibility of more public servants to use their publicly entrusted positions to enrich themselves. High PDI means that corruption situations, which undermine the rights and equality of people, are more tolerated because the country itself tolerates inequality and authoritarianism. Hence, scandals and power abuses occurring in high PDI contexts tend to be covered up and tolerated more than in low PDI contexts. Power and culture also play a role in the in-group and out-group performances. Powerful members in high PDI countries may try to increase the power and influence of their in-group much more than ordinary people in the out-groups. They may do so even through corruption as this is “expected” of them.

In addition, the laws and regulations in high PDI countries may be set as advantageous for powerful people making situations of corruption at easy reach.

The institutions and organizations of high PDI societies are usually characterized by a strong respect for authority and centralized decision-making. Subordinates do not challenge authority and change is achieved only by revolutions often characterized by violence, resistance, and repression. Political leaders in those high PDI societies base their powers on family or friends and citizens and their relations with citizens are often characterized by emotions. Civil servants and elected officials in high PDI countries enjoy a significant degree of autonomy from public pressure resulting in higher level of discretion and arbitrariness. It should be noted that unequal distribution in public services, typical in high PDI countries, are often attributed to expectations and norms in international relation and not necessarily related to hopes for individual financial gains.

Uncertainty Avoidance Index and Corruption

The second dimension, the uncertainty avoidance index (UAI), measures a society’s (in)tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. Hofstede defines uncertainty avoidance as “the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations.”42 It reflects the extent to which members of a society attempt to cope with anxiety by minimizing uncertainty, the occurrence of unknown and unusual circum-stances. People in cultures with high uncertainty avoidance (high UAI) tend to manage or avoid risks, and proceed with changes with carefully planned strategies. They implement highly structured organizational activities and valuing rules and regulations while inhibiting ambitions and discouraging fast changes. On the contrary, people and cultures with low uncertainty avoidance (low UAI) accept and are more tolerant of change, feel comfortable in unstructured situations, and try to have as few rules as possible.

As high UAI cultures are generally characterized by highly structured and regulated organizational activities they would logically leave little room for corrupt activities. However, if the formal rules do not specifically define “inappropriate behaviors” financial auditors are less likely to challenge the manager. Also, there is a possibility that high UAI (especially when combined with high IND) may urge public servants to the creation of wealth, including illicit wealth creation, as a way to diminish uncertainty and maximize financial security. Countries with low UAI include Denmark, Singapore, Sweden, Hong Kong, Vietnam, China, Ireland, Great Britain, Malaysia, India, Philippines, and the United States.43 Countries with high UAI include Greece, Portugal, Guatemala, Uruguay, Belgium, Malta, Russia, El Salvador, Poland, Japan, and Serbia.44

Some have argued that within those societies where a “large gap is perceived to exist between the degree of uncertainty avoidance desired (valued) and the uncertainty avoidance provided by the legal structure on commercial and public sector activities (practice)” corruption may be seen as a tool for restoring fairness.45 Other strategies for reduced uncertainty may include bribery, fraud, and political corruption as a way to establish a favorable and reliable relation with politician or public service administrator.

Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV) and Corruption

Extreme individualism and extreme collectivism are the opposite poles of a second most important global dimension of national cultures, after power distance. The individualism (IDV) index measures the degree of individualism (independence and freedom) versus collectivism (integration and loyalty). Hofstede defines this dimension as follows: “Individualism pertains to societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him-or herself and his or her immediate family. Collectivism as its opposite pertains to societies in which people from birth onward are integrated into strong, cohesive, in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange of unquestioning loyalty.”46 In individualistic societies, the stress is put on personal achievements and individual rights. People are expected to stand up for themselves and their immediate family, and to choose their own affiliations. In contrast, in collectivist societies, individuals act predominantly as members of a life-long and cohesive group or organization with mutual expectations of protection, loyalty, and special treatments for the in-group member of the family, organization or society. The strong cohesion of in-group dynamics goes hand in hand with the exclusion of members of other groups.47

Among the various key differences between collectivist and individualist societies is their relation to harmony, respect, and honesty. In collectivist societies and institutions (e.g., family), “harmony should always be maintained and direct confrontations avoided.” On the contrary, in individualistic societies “speaking one’s mind is a characteristic of an honest person.”48 In the workplaces of collectivist societies employees are members of in-groups that will pursue the in-group’s interests, management is management of individuals and in-group customers get special treatments (particularism). In the workplaces of individualist societies employees are “economic persons” who will pursue the employer’s interest if it coincides with their self-interests, management is management of individuals and every customer should get the same treatment (universalism).49

The GLOBE study builds on Hofstede IDV dimension but specifies it as institutional collectivism and in-group collectivism. Institutional collectivism refers to the degree in which a society, institution, or organization practices encourage and reward collective distribution of resources and collective action (e.g., group rewards rather than individual rewards). In-group collectivism refers to the degree to which individuals express pride, loyalty, and cohesiveness in their organizations and families. “Organizations in which members hold loyalty more to the organization rather than to personal gain would be an example of high in-group collectivism.”50 The GLOBE study contributes to understanding the nature of accountability and how it varies in individualistic and collective societies. Individualistic cultures are more likely to rest accountability on the responsibility of individuals. Hence, clear documentations with lists of signatures and clear job descriptions and reporting would be essential to establishing individual accountability and creating lines of communication. On the other hand, accountability (and therefore blame) in collective cultures would be more likely to rest in groups and rarely traceable to individuals. Hence, written documents and long lists of signatures would rarely be used.51

Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS) and Corruption

This dimension is not about gender but desirability of assertive behavior against the desirability of modest behavior. Because of the obvious gender generalizations implied in this terminology, users of Hofstede’s work sometimes prefer to describe this dimension as Quantity of Life vs. Quality of Life.52 Although most men exemplify the “masculinity” characteristics, the cultural behaviors expressed by this dimension are relative and gender neutral. Hofstede defines this dimension as follows: “A society is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender and concerned with the quality of life. A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.”53

Another confusion in the literature is between masculinity/femininity with individualism/collectivism. These dimensions are related but distinguished as masculinity/femininity are more about a stress on ego and on relationships.54 From a government and public service standpoint, feminine societies are characterized by welfare systems with a regulated system of assistance to the poor and marginalized sectors of society. Masculine societies on the other hand are better characterized by performance and a general support of the strong. Feminine cultures are characteristic of more permissive societies while masculine cultures are corrective societies. Feminine cultures place more value on relationships and quality of life whereas masculine cultures value competitiveness, assertiveness, materialism, ambition, and power. In feminine workplaces, management is done through intuition and consensus while masculine workplaces are decisive and aggressive. In feminine culture people work in order to live (they value leisure over money) while in masculine cultures people live in order to work (they value money over leisure). Feminine cultures expect rewards based on equality while masculine cultures expect them based on equity.55

GLOBE distinguished this dimension into Gender Egalitarianism (the degree to which a collective minimizes gender inequality) and Assertiveness (the degree to which individuals are assertive, confrontational, and aggressive in their relationships with others). GLOBE introduces also other cultural dimensions in relation to Hofstede’s MAS dimension: Performance Orientation (the degree to which an organization or society encourages and rewards group members for performance improvement and excellence) and Humane Orientation (the degree to which individuals in organizations or societies encourage and reward individuals for being fair, altruistic, friendly, generous, caring, and kind to others). This last dimension is evidenced by a focus on social responsibility, public service, and an expectation that members work well with others. Along these specifications, other studies have shown how MAS dimension plays a role in mental programming at an ethical crossroad. For example, people in high MAS culture have a “societal expectation” to achieve financial goals in “now or never” and “big and fast” ways. Even in front of unethical or corrupt situations, people who are too hesitant to take the advantage of the “big” opportunity could be seen as cowardly. Therefore, MAS cultures are more likely to overlook ethical transgressions in business transactions, leading to the toleration of unethical behavior and the pervasiveness of corrupt practices.56

Culturally Integrated Anti-Corruption Model

Effective anti-corruption teaching in public service should seek an integrated approach to understand the nature, causes, and solutions to corruption. The so-called moralist approach (individual responsibility) is basic but insufficient. A functionalist approach (management responsibility) is also necessary but needs to be integrated with an institutional approach (institutional responsibility) based on system analysis and good governance capacity development. Upholding the rule of law by fostering transparency and accountability in the public sector serves not only as means to counter corruption but also as fundamental conditions of good governance. However, it appears that cultural values with the above-described cultural dimensions have a significant impact on either facilitating or restraining the perception and practice of corruption in public service.

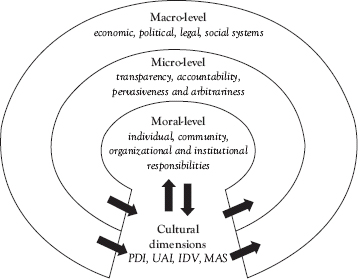

The significance of cultural dimensions on corruption is relevant to plan, implement, and evaluate anti-corruption plans in specific cultural contexts and sectors of society. Cultural dimensions also matter for understanding the causes, consequences and dynamics of corruption. An integrated approach that includes intervening factors like economic level, political capacity, legal and social systems (macrolevel) with transparency, accountability, pervasiveness, and arbitrariness factors (microlevel) needs to be integrated with the moral dimensions (individual, community, organizational, and institutional responsibilities) and cultural dimensions (power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity). Cultural dimensions, although minimized in the institutionalization processes driven by globalization and localization, permeate and influence the moral, micro-and macrolevels. Figure 8.2 represents an integrated model with the interception of culture in the understanding of corruption perception and practices. The arrows represent the influence of culture on the moral, micro-and macrolevels. But they also represent the fact that this is not a mechanic model. Cultural values are practices that evolve in time and in the interaction with systems, institutions, organizations, norms, and different cultural values.57

Figure 8.2. Culturally integrated anti-corruption model.

Culture is key to understanding corruption, but not the only explanation. Moral responsibilities, management level issues (micro), and systems (macro) influence the perception, practices, and changes in corruption. Recognizing the intersecting influences that cultural dimensions have on corruption can be predictors of ethical issues within certain national and cultural environments. The inclusion of culture in the study of corruption could lead to developing more appropriate and effective practices and policies to mitigating corruption. Students in public service can develop their cultural intelligence, essential for helping individuals and organizations in dealing with culturally embedded corrupt practices.

Integrated models are common in the study and fight of corruption. The World Bank has been on the forefront of proposing a comprehensive plan to effectively combat corruption. They recognize the importance of engaging all stakeholders (political leaders, champions amongst public servants, civil society, media, academics, the private sector and international organizations) to effectively tackle the causes and consequences of corruption.58 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also has a comprehensive plan for fighting bribery and corruption. Recognizing that integrity is the cornerstone of good governance and anti-corruption, they articulate mechanisms for promoting, developing, and measuring public service integrity at various levels.59

Integrated models are also common in the measurement of worldwide perceptions of corruption. The World Bank, the World Economic Forum, the Economic Intelligence Unit, Gallup International, among others, have been producing numerous survey studies that Transparency International publishes yearly in the Corruption Perception Index (CPI). The annual CPI ranks 183 countries in their perceived levels of public sector corruption on a scale from 10 (very clean) to 0 (highly corrupt). The CPI is just one of the many other tools that measure corruption. However, its simplicity and utility is also due to the integration of several other surveys from independent institutions.60

The United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), adopted by the General Assembly on October 31, 2003, is another example of integrated aspects of corruption and anti-corruption methods. Extending the 1996 United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, UNCAC is the first legally binding international anti-corruption instrument comprised of various levels of interventions for prevention, criminalization, international cooperation, and assets recovery.61 In spite of the long road ahead in technical assistance to effectively link the convention to national and local laws and regulations, this convention will impact anti-corruption only through the effective engagement of sectors and proper understanding of cultural values. Knowledge of these integrated approaches and international conventions is must for anti-corruption educations and training.

Lessons for Teaching Anti-Corruption

Effective anti-corruption education for public servants must integrate appropriate intercultural studies. While respecting the diversity of public service and public administration programs, accreditation agencies like the National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration (NASPAA) should promote and monitor curricula in the teaching of anti-corruption. This should be recognized beyond fiscal responsibility. Public corruption must be examined in the context of cultural competencies, international relations, and local/federal government relations. It must be perceived beyond individual ethical “issues” and articulated within the promotion of good governance practices and institutional capacity development.

The following is a list of recommendations for teaching anti-corruption in public service through a culturally intelligent and multilevel model. As described in this study, effective anti-corruption trainings and educational programs must integrate the study and application of corruption from a systemic, technical, ethical, and intercultural perspective.

1. Implement anti-corruption across the curricula. A comprehensive and integrated approach to anti-corruption cannot be covered only in ethical courses. It needs to be articulated across other courses and disciplines starting from institutional systems, and cross-sector analysis. It needs to be integrated with technical, legal, and management elements and it needs to comprehend the cultural dynamics in ethical decision-making and public service administration.

2. Critically analyze corruption. Is corruption bad or good? Corruption may be an international unacceptable problem but not for the same reasons that Westerners put forward.62 The general perception in Western circles is that corruption can just be eliminated with political will. In reality corruption needs to be seen in all of its aspects, including its diverse relations with development. For example, what matters is not just “how much” corruption there is in a country but what corrupt public officials do with the money. While African corruption money generally ends in the pockets of politicians, Asian and East European corrupt state officials tend to reinvest the money in sensible business projects in their countries.63

3. Develop diversity awareness. To recognize the cultural diversity in the perceptions of corruption practices teaching activities should include real case studies and experiential learning through international projects for capacity building. In culturally diverse classes and trainings with diverse participants, instructors should stimulate learning through assessments on diverse perceptions on corruption. For example, the answers to what appear to be obvious questions may vary greatly in a culturally diverse setting and could spur interesting debate. Using real life case studies in corruption across cultures could stimulate a lively debate on ethical decision-making in cross-cultural perspectives.64

4. The 4P approach: Principles, Prevention, Prosecution, Protection. Anti-corruption curricula may not be the ultimate solution to corruption but it is essential for instilling competent and responsible principles in public servants. As in the Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), the anti-corruption principle of the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) needs to be integrated in training modules and curricula for good governance and responsible business practices. Principles and definitions are important but not enough. They need to be articulated along practical skills, competencies and for preventing corruption, prosecuting criminals, and protecting victims.65

Teaching anti-corruption can no longer be an elective in public service education. However, we need to implement effective educational programs that integrate theory with practice, principles with experience, functions with structures, and moral decisions with cultural dimensions.

Conclusions and Applications

Corruption is recognized as one of the world’s greatest challenges. But corruption is not just about ethics. It is also about how the government is set up and managed. That is why improving the capacity, accountability, and transparency mechanism of a government is fundamental in fighting corruption. This study has presented an overview of corruption in the context of cultural diversity and the moral, social, organizational, and institutional responsibilities of public servants. We suggested a culturally intelligent and multilayered model for integrating anti-corruption in teaching and training for public servants. Educating socially responsible public servants in a globalizing world would require implementing programs, degrees, curricula, and trainings that integrate ethical decision making with the awareness of structural, technical, and cultural implications of anti-corruption. It would also require seeing public service not in a vacuum of functional administrations but in relation to rights and responsibilities across sectors and culture.

Public service management programs should reconsider the role that culture has in corruption practices and revisit their curricula and learning outcomes. Public servants should be culturally competent. That is, they should be recognizing the assets and limitations made by cultural dimension on corruption’s perceptions and practice. Power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity are not the only cultural dimensions or factors explaining corruption. However, their influence to ethical decision-making and correlation to perceptions of corruption have been demonstrated by numerous empirical studies and explained in various theoretical works. Universities and training organizations alike should take culture’s impact on corruption into serious consideration when designing educational and professional programs.

As government administrations operate more and more in interlocal, interregional, and international dynamics, the need for understanding and dealing effectively with cultural dimensions is no longer an elective in good governance education. Such education should also integrate the contemporary corruption challenges and effective anti-corruption strategies emerging from national agencies, international agencies, and nongovernmental organizations. While the model here presented would require further testing and adaptation into curricula development, it suggests the inevitable interception that culture has in corruption perceptions and practices. It also suggests that teaching anti-corruption in public service education is a must and it should be integrated with adequate moral, micro, macro, and cultural dimensions.

Key Terms and Definitions

Bribery: An offer or receipt of any gift, loan, fee, reward or other advantage to or from any person as an inducement to do something that is dishonest, illegal or a breach of trust, in the conduct of the enterprise’s business.66

Clientelism: This is an informal form of social organization characterized by patron–client relationships between people of different social and economic status: a “patron” (relatively powerful and wealthy) and his/her “clients” (relatively less powerful and wealthy). The relationship includes a mutual but unequal and often corrupt exchange of favors.67

Collectivist culture: Relative to those societies in which people from birth onward are integrated into strong, cohesive, in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange of unquestioning loyalty.

Collusion: This is a usually secretive act of cooperation or collaboration among two or more parties to mislead or defraud others of their rights.

Cronyism: Favoritism shown in treatment of friends and associates, without regards to their objective qualifications; could be treated as a form of corruption.

Embezzlement: The illegal taking or appropriation of money or property that has been entrusted to a person but is actually owned by another. (In political terms this is called “graft,” which is when a political office holder unlawfully uses public funds for personal purposes.)68

Episodic corruption: This type of corruption occurs when honest behavior is the norm, corruption the exception, and the dishonest public servant is disciplined when detected.

Extortion: A threatening or inflicting harm to a person, their reputation, or their property in order to unjustly obtain money, actions, services, or other goods from that person (Blackmail is a form of extortion.)69

Feminine culture: Relative to those societies when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

Grand corruption: This type of corruption generally associated with high-level politicians or officials and it involves relatively large bribes from contractors or other corporations.

Individualist culture: Relative to those societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family.

Kickback: An illegal secret payment made as a return for a favor or service rendered.

Masculine culture: Relative to those societies when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life.

Nepotism: The practice or inclination to favor a group or person who is a relative when giving promotions, jobs, raises, and other benefits to employees. This is often based on the concept of “familism” that leads some political officials to give privileges and positions of authority to relatives based on relationships regardless of their actual abilities.70

Patronage systems: They consist of the granting favors, contracts, or appointments to positions by a local public office holder or candidate for a political office in return for political support. Often patronage is used to gain support and votes in elections or in passing legislation. Patronage systems disregard the formal rules of a local government and use personal instead of formalized channels to gain an advantage.71

Petty corruption: This type of corruption often involves lower-level public officials and generally involves smaller amounts but more frequent transactions. This is also known as administrative corruption or retail corruption.

Power distance: A cultural dimension defined as the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

Speed money: These are bribes paid to quicken the delivery of services delayed by bureaucratic holdup (red tape) and shortage of resources.

Systemic corruption: Channels of malfeasance extend upwards from the bribe collection points, and systems depend on corruption for their survival.

Uncertainty avoidance: A cultural dimension defined as the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations.

Study Questions

1. Why are the values of public service instrumental to understand corruption in its general definition?

2. What is institutional theory and how does it help to understand corruption in public service?

3. What are the differences between the culture of corruption, cultures, and corruption and the corruption of cultures?

4. How does the study of cultural dimensions influence and shape the understanding, perception and practice of anti-corruption?

5. Would you be able to give an example of behavior that is considered “corrupt” in one culture and “tolerated” or “culturally accepted” as a norm in another?

6. How does power distance affect the perception and practice of corruption? Give an example from your own culture and one from another culture.

7. How does individualism/collectivism affect the perception and practice of corruption? Give an example from your own culture and one from another culture.

8. How does uncertainly avoidance affect the perception and practice of corruption? Give an example from your own culture and one from another culture.

9. How does masculinity/femininity affect the perception and practice of corruption? Give an example from your own culture and one from another culture.

10. What other cultural dimensions affect the perception and practices of culture? Give an example.

Additional Reading

Callahan, D. (2004). The cheating culture: Why more americans are doing wrong to get ahead. Orlando: Harcourt.

Eicher, S. (2009). Corruption in international business: The challenge of cultural and legal diversity. Farnham, England: Gower.

Haller, D., & Shore, C. (2005). Corruption: Anthropological perspectives. London: Pluto.

Hofstede, G. H., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. New York: McGraw-Hill.

House, R. J. (2011). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Huntington, S. P., & Harrison, L. E. (2000). Culture matters: How values shape human progress. New York: Basic Books.

Smith, D. J. (2007). A culture of corruption: Everyday deception and popular discontent in nigeria. Princeton: Princeton University Press.