3

Leadership and Organizational Networks

A Relational Perspective

The more we grasp the kind of complex interaction Burns, Lovaglia/Lucas/Baxter, and Flowers write about, the more important it is to understand not just leaders, but the groups and social networks they lead. Philip Willburn and Michael Campbell employ insights from social networking theory to do just that. This knowledge can help you get your vision out effectively to a large number of people that you communicate with directly. In the following essay, they provide a model that you can use to analyze the social networks you influence. As leaders, we often believe that if we develop a plan and share it, the people who report to us will implement it because it is their job to do so. But people act like people, and not necessarily according to an organizational chart. Their energy to implement any plan is dependent on (1) whether the communication gets to them in a way that is motivating and sparks their imaginations, and (2) who they listen to and what those people say about the plan.

Every day in our work life, we are creating, developing, maintaining, or neglecting informal relationships and organizational networks. These informal networks can be anything from the people we have lunch with, to the mentors we choose at work, to the people who help us get work done outside the “formal” work procedures. Once considered a nuisance by traditional management, these informal networks are now being used to leverage creativity and talent within the workplace.

Two main principles have emerged from the research on leadership and organizational networks regarding the role of leaders and their relationships to these networks:

1. The ability to lead is directly affected by the networks a leader builds.

The structure of a leader’s network affects how a leader shares and receives new ideas, who a leader trusts for information, and how leaders can locate resources outside their traditional roles. Leaders should be aware of their relationships. Building a diverse network (not just a big one) of associates can greatly influence the success of a leader.

2. A leader’s behavior influences the type of network structure that develops in organizations, which consequently impacts organizational performance.

Transformational leaders are aware of the network they are reinforcing and its impact on their organization. For example, is a leader reinforcing hierarchy or promoting collaboration? Is a leader creating decision bottlenecks that restrict information flow, or connecting information hubs across the organization? Is a leader encouraging a robust network that can withstand changes in the environment, or creating a brittle network that breaks with the slightest change? Creating the conditions for robust relationships to develop is critical for the twenty-first-century organization.

Awareness of Organizational Networks

A leader must be aware of the organization’s informal networks to understand how the organization is truly working, not just how it is supposed to work on paper (Cross & Parker, 2004). Communication rarely flows like it does in an organizational chart. Instead, it moves through informal communication networks, which may have nothing to do with how the organization is structured. A leader must understand and leverage these informal organizational networks to avoid network insularity, promote network diversity, and facilitate organizational communication. Leaders must avoid network insularity to ensure that their perceptions of the organization are not biased toward only one set of opinions. Having a biased or “insular” network leads to poor decision making and potentially negative consequences for organizations. Some of the original research on leadership and insularity discussed open versus closed systems (see Meyer [1975] for insight into some of the first studies). For example, would Ken Lay, former CEO of Enron, have acted differently if he had received perspectives and ideas outside his inner circle of executives who were part of the Enron scandal? The case of the Enron executive committee is one of the extreme instances of network insularity that unfortunately had very bad consequences for its shareholders and the American people. Even if leaders avoid network insularity, they often assume communication and work flows in their organization based on their personal networks. This assumption, however, is often false and can produce a skewed sense of how the organization functions. A leader receiving communication from only one informal network will receive only the generalized opinions from that network, which may be very different than another informal network. A leader with insight into multiple organizational networks will have a more accurate understanding of the organization.

CASE EXAMPLE • A Great Vision Going Nowhere

One of the authors, Philip Willburn, recently worked with an executive committee struggling to disseminate its vision throughout the organization. A recent climate survey showed the organization was in the top quartile in customer focus, core values, and creating change, but in lowest quartile in vision and strategic direction. The organization’s senior leader recognized that communication was not getting down to the employees but didn’t understand why. She communicated her vision frequently with her executive team, did a few town halls each year, and sent a number of organization-wide emails. She assumed the members of her executive team were using their channels to communicate the vision as well. After speaking to her, Wilburn decided to do a quick diagnostic test on the executive committee’s social network.

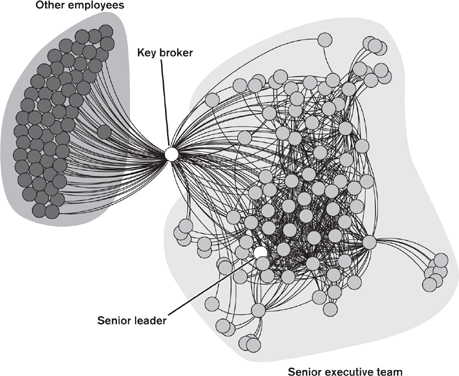

In his network assessment, he asked two questions: “Who did you receive the organization’s vision from?” and “Who do you then communicate the vision to?” After compiling network analysis results, he could see multiple channels of vision statements and many interpretations of the visions (Figure 3.1). Seventy percent of the executives reported that they received the vision from the senior leader. However, 60 percent reported they also received the vision from the chief technical officer, 50 percent from the director of strategic initiatives, and 50 percent from the director of operations. With the exception of one executive (a key broker), most of the executives spent their time communicating the vision to each other (Figure 3.2). The senior leader was completely unaware of this communication insularity.

Figure 3.1 Network of who the executives received their vision from.

Figure 3.2 Network of who the executives communicated the vision to.

Interviews with the senior leader’s team revealed that the leader prided herself on creating a clear and compelling vision, and was put off by people who could not articulate it exactly the way she wanted it articulated. In one instance, a division manager asked the senior leader why the services segment of the business was not included in the vision. She quickly responded that it was included, and then berated the division manager for not appropriately listening to the vision. The fear of being criticized for miscommunicating the vision kept the executive team from getting the vision out to the organization and admitting this to her. The organization was suffering, not from a lack of a clear vision, but from the lack of effective openness, inclusiveness, and dissemination. The senior leader did not have a communication problem, as she originally thought. She had a network insularity problem.

In the case study above, the senior leader was unable to get her vision out to the organization because her executives told her what she wanted to hear, not what was actually going on. And because of her network insularity, she did not have a way of finding out what was going on. The issues of insularity can be counterintuitive, because leaders want to surround themselves with trusted, competent people (often people like themselves). Insular networks also occur as people work with each other. They become more like-minded and develop similar perspectives. But as leaders create an insular network, they shed other relationships that might give them different, more helpful perspectives.

Network Diversity

The opposite of network insularity is network diversity. The senior leader in our case example was unaware that her vision was not getting out and that the executive team was the choke point. By examining her individual relationships, we discovered that she had a large network of relationships, with many ties to her customers and subject matter experts across her organization, but that’s where her network stopped. She did not have insight into the executive team’s fear of communicating her vision incorrectly, nor did she have insight into what her middle managers were receiving about the vision. Her general lack of relationship diversity kept her from seeing what was “really happening” in her organization. For leaders, increasing network diversity and fighting off insularity is one of the most challenging tasks. It is difficult for a leader to forge new relationships, but the downside can be a lack of organizational perspective.

Leadership Positions in Organizational Networks

When you receive information from a corporate mass email about future organizational changes, do you believe the message outright, or do you verify that information with a friend or trusted advisor? Whom do you believe more, the mass email or your friend who has worked at the company for ten years? If the number of people who go to your friend for the same advice is large, your friend is the network’s “opinion leader,” and he or she can have a big impact on whether employees believe what management is saying.

Through research on organizational networks, four leadership network positions have been identified as critically influential (Balkundi, & Kilduff, 2005). These leadership positions are often not occupied by leaders formally identified in a company’s organization chart, but by an informal leader. Conflict, miscommunication, and organizational confusion can arise when the formally recognized leader is not aware of or does not work with the informal network leader. Both informal and formal leaders must be aware of these four positions and understand how to work with each other to avoid detrimental outcomes.

Popularity

A person filling the popular position in a network will have numerous relationships (incoming and outgoing ties) within an organization or team. The person has influence because of the sheer quantity of interpersonal relationships maintained and managed on a daily basis. This person is often the lifeblood of an organization, a rallying point, and someone who can either help the organization achieve its mission or undermine its success. Formally recognized leaders who are also popular have high-performing teams (Balkundi & Harris, 2006; Brass, 1992; Fielder, 1955). The opposite can be true as well; team performance decreases when formal leaders are not the popular network leaders.

Being the popular leader, although appealing, also has its drawbacks. A popular leader is popular in the informal network because she is able to respond to people and maintain relationships with even the lowest-level employees in the organization. The most difficult part of being the popular leader is managing the reciprocity of ties. When teams and organizations become large, the popular leader must manage a larger number of relationships, requests, and communications on a daily basis.

Prestigious leaders are those who have valuable information that other people in the network want. A person in this position might be a trusted mentor whom everyone knows they can depend on to give good advice, or the information technology support person who goes the extra mile to make sure everything is working. When the number of different people coming to a leader for advice is much larger than the number of people the leader asks advice from, then that leader is considered the prestigious leader in the network (Balkundi, Barsness, & Michael, 2009). Prestigious leaders are also known as information hubs, experts, and consultants. These leaders rarely want to be in the center of the flow of information, but because of their known expertise, they become centralized in the organization. In small teams, when the formal leader is also the prestigious leader, these teams experience less conflict and better overall team performance. However, when the formal leader is also the prestigious leader in large networks, he or she may quickly become a communication and decision-making bottleneck to the organization.

Facilitation

To avoid the bottleneck phenomenon, many leaders try to “borrow” prestige or popularity by becoming facilitators of information. These network facilitators try to limit the total number of relationships they have and just focus on getting to know and develop the trust of the few prestigious and popular leaders in the network. This allows a leader to gain social capital through intermediaries, without becoming a bottleneck (see Bonacich, 1987; Bonacich & Lloyd, 2001; Moody, McFarland, & Bender-DeMoll, 2005). This type of network leader leverages “ghost” influence over an organization by having the trust and ear of the popular leaders. When the formal leaders are not facilitators, it is critical that they work to find this person, because the facilitator has the trust of the popular leaders and can either energize or undermine the formal leaders’ goals.

Brokerage is the ability of a leader to bridge fragmented groups within networks. Fragmentation is caused by various organizational conditions, such as different functional areas, geographic locations, social identities (e.g., ethnicity, race, gender), and hierarchal positions. Brokers connect fragmented subgroups by acting as a bridge between them and are sometimes called the “go-between” people in an organization (for a more detailed description of the betweenness-centrality metric, see Freeman, Roeder, & Mulholland, 1979/1980). This position yields the greatest amount of influence in a network and has been the best predictor of future leadership promotions (see Balkundi, Kilduff, Barsness, & Michael, 2007; Burt, 1992; Krackhardt, 1990).

When the formal leaders are also the brokers, they work as coordinators and information conduits across multiple groups and are shown to help integrate specialists, avoid redundant uses of resources, and connect people. There is a downside, however, to the formal leader being the broker. Leader brokers can distort information between groups, increase intragroup conflict, and decrease team viability. The formal leader in this position must be cognizant of the potential distortion of information between subgroups and work to uphold the highest integrity when performing this function. The broker must be adept at translating between significantly different subgroups.

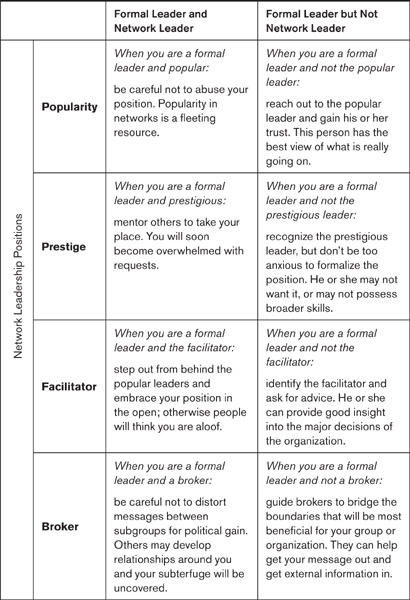

Regardless of who holds these network leadership positions, the formal leader must understand how to leverage these positions within the organization. Table 3.1 provides advice to formal leaders when dealing with network leadership positions.

Conclusion

People are communal beings who naturally create social networks that largely determine the collective attitudes and behaviors of their culture. Trying to fight this or circumvent it is as pointless as trying to control the weather. Transformational leaders, therefore, consciously work with networks to foster transformational change that does not engender great resistance but is in alignment with the norms, values, and shared ways of living together that are the basis for the network’s culture and way of seeing the world.

Table 3.1. Advice for Formal Leaders in Dealing with Network Leadership Positions

Since 2006, Philip Willburn has been the director of network sciences at OE Consulting, a leadership and network analytics firm based in Arlington, Virginia. He is a social network analysis expert with formal training in dynamic network analysis and computational organizational theory. Willburn specializes in identifying and characterizing leaders and emerging leaders within organizational and social networks. He provides consulting services to Fortune 500 companies and governmental organizations and hosts workshops on leadership and social network topics in the United States and abroad. He holds an MA in organizational communication from the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

Michael Campbell is a research associate at the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL), a nonprofit educational and research institution dedicated to the understanding and practice of leadership. As a member of CCL’s Research & Innovation division, Campbell’s work focuses on research and client solutions in talent management and senior executive leadership. His work on social networks focuses primarily on how network development influences the effectiveness of leaders and the behaviors that lead to the creation of high-functioning networks. He holds a BS in business administration and an MA in communication from the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.