5

Dancing on a Slippery Floor

Transforming Systems, Transforming Leadership

Diana Whitney and Amanda Trosten-Bloom introduced us to the psychological shift in progress from focusing on problems to discovering and reinforcing the capacities people and organizations possess, so that we can have the confidence to implement desired future visions. In this essay, new ways of thinking, pioneered in the physical and biological sciences, illustrate how we as contemporary leaders can reframe our responses to twenty-first-century challenges. Building on the work of Margaret Wheat-ley (1992) and others, Kathleen Allen summarizes major themes in the advances from Newtonian to quantum physics and from an industrial to a biological paradigm. She then applies these lessons to leadership in ways that work with, rather than fight against, natural processes, showing how you can build your capacity for experiencing greater ease and less resistance to the challenges of leading in today’s world.

How do we know when our thinking needs to be transformed? One way is when the beliefs and assumptions we have no longer provide a way to explain what is going on in our life and organizations. Another way is when our actions that flow from our beliefs require more energy and resources to achieve the same or fewer results (Lynch & Kordis, 1988).

There is a cost to holding on to old thought patterns and behaviors. We tend to narrow our thinking and collect only data that reinforce our point of view, which constricts our life and the meaning we make of it. I have found that I can transform my thinking by studying different disciplines and taking concepts from them to apply to my field of leadership. Discovering how different fields look at things enriches and challenges my own paradigms and underlying assumptions and raises my practice and my effectiveness when I work with organizations.

I have been fascinated by biomimicry (Benyus, 2002), which is the study of how nature can be used as a mentor, model, and measure for designing sustainable systems. Nature’s underlying design creates infinite possibilities found in the following nine principles:

• Nature runs on sunlight.

• Nature uses only the energy it needs.

• Nature fits form to function.

• Nature recycles everything.

• Nature rewards cooperation.

• Nature banks on diversity.

• Nature demands local expertise.

• Nature curbs excesses from within.

• Nature taps the power of limits by maximizing the benefits of the constraints of the ecosystem like temperature ranges, soil fertility, rainfall, and so on.

These principles lead me to see organizations and their cultures, processes, structures, and leadership differently. For example, sunlight is a constant and abundant energy source that plants transform into a life-giving energy. Do we have an equivalent to a constant-renewal energy source in our organizations?

The principle of nature using only the energy it needs drives me to look for wasted energy in organizations. I have discovered that any system designed to control something uses more energy than it needs. And there is always a different design process that can achieve higher results with less energy (time, money, staff, or attention).

Over the last twenty-five years, I have used the new sciences and the shift to their underlying systems theories as a source for seeing differently, transforming my thinking, and enriching my practice to meet the extraordinary challenges of the twenty-first century.

From Newtonian to Quantum Physics

The shift from Newtonian to quantum physics is fundamental to the worldview shift from separation to connectedness. Newton saw the universe as a giant machine. The machine metaphor has influenced the structure of our organizations and our thinking about leadership. The machine needs a power source to run it, hence our framework of leaders as sources of motivation and vision and the great man theory of leadership. The shifts from Newtonian to quantum physics include the following:

• Closed to open systems: Newton’s physics assumed a closed system, while quantum physics sees the world as a highly connected and open system (Capra, 1975, 1992, 1996).

• Parts to whole: Newton’s mechanistic metaphor brought a focus on the parts instead of the whole. The phrase that people are “cogs in an organization” is a familiar extension of this logic. The quantum world is filled with connections and can be understood only from the perspective of the whole. Deming (1986) and the total quality movement, with its appreciation of overall process and stakeholders, is an example of a shift from the focus on the individual (part) to the system.

• Focus on the individual to focus on the field: The Newtonian focus on parts is reflected in much of the leadership literature, where the unit of analysis is the individual leader. The quantum world brings the focus to the whole reflected in field theory, which holds that invisible fields, like gravity or a magnetic field, exert significant influence on the behavior of all the parts of the system (Capra, 1996; Wheatley, 1992; Zohar, 1997). Organizational culture has the properties of an invisible field and influences how individuals behave at work. This helps shift thinking about leadership and change from “how do I influence the individual?” to a much more powerful question of “how do I influence the culture of an organization?”

• Opposition splits to opposition necessary for wholeness: One of the strangest discoveries of modern physics is the wave/particle duality (Wheatley, 1992; Zohar 1997), which moved us from a world of either/or to a world of both/and. It challenges us to think in terms of both potentialities and paradox within our organizations (Handy, 1994; Wacker & Taylor, 2000). The idea that opposition is necessary for wholeness and sustainable solutions has helped me significantly to see tensions as promising and resistance as something to pay attention to. Often, resistance can actually catalyze change in an organization. However, if we spend our energy shutting it down or avoiding it, we lose the power embedded in resistance to leverage sustainable change.

From Industrial to Biological Paradigm

The 2008 Futurists magazine introduced the new biological paradigm as the framework for the twenty-first century and juxtaposed it with the twentieth-century industrial framework (Brown, 2008). A biological paradigm looks to nature and the study of life and living systems to think about how to produce things and structure and lead our organizations (Benyus, 2002). Some key shifts include the following:

• Perfectibility to functionality/fit: Living systems are constantly evolving and adapting. The criterion for effectiveness is a focus on functionality and fit with the environment, allowing an organism to mutate to survive. It lets go of the search for perfection that an industrial mental model pursues.

• Universally applied best practice/universally applied to emergent practice designed to fit a unique context: The industrial paradigm looked for a “one size fits all” framework. The concept of best practices assumes that once a best practice is identified, it can work in any context. The biological paradigm understands that in living systems, context matters. What works in one ecological region doesn’t work in another without significant additional resources.

• Mass production to mass customization: Mass production was a strategy used in an industrial paradigm to scale the quantity and profits of production. The science of biomimicry (Benyus, 2002) looks to nature to understand how to design products that respond to the uniqueness embedded in all living systems. YouTube and Facebook are examples of mass customization. They both create a cooperative platform that allows diverse individuals to create their own pages or videos that reflect their uniqueness. Like nature, they reward cooperation and bank on diversity to sustain interest in these mediums.

• Stable structures to adaptability, flexibility, and agility: An industrial mental model is based in a hierarchical organizational structure that ensures stability and works for stable environments. However, nature is constantly adapting and evolving and is designed with interdependence and connectivity. Organizations that are designed to leverage networks can be more flexible and agile, which is required to keep pace with today’s external environment. Wikipedia is an interesting example of something that is designed from a biological paradigm. It is open sourced and allows multiple people to shape the content. The goal of Wikipedia is one of functionality, not perfection. Its design reflects a living system instead of the stability of a Webster’s dictionary.

From Mechanistic Bureaucratic System to Complex Adaptive System

The next shift is from mechanistic bureaucratic systems to complex adaptive systems (CAS), which are an outgrowth of chaos and complexity theory in science (Glieck, 1987; Hazy, Goldstein, & Lichtenstein, 2007; Olson & Eoyang, 2001). Some shifts include the following:

• Static rigid structure to coevolving system: A mechanistic framework requires a defined boundary. All the relationships are embedded in the design and do not change unless intentionally redesigned. The saying “change starts at the top” reflects the assumption that change is directed, not cocreated. In a CAS, there are many variables, each one influencing the others (Clark, 1985).

• From control dynamics to unconstrained dynamics: A CAS assumes the world is filled with open systems (Jennings & Dooley, 2007; Schwandt & Szabla, 2007) that influence other systems (Stacey, 1992). In a mechanistic bureaucratic system, the goal is to control the dynamics of the system. Its hierarchical organizational structure splits labor and management, and management is the place where control, resources, and knowledge are held. A hierarchical organizational structure assumes that cause and effect exist, are known, and can be used to generate leadership and action. In a CAS, the number of variables in play are numerous and expanding all the time. Cause and effect do not exist. It begs the question of what leadership looks like in a world that doesn’t operate with linear cause and effect. Expecting the unexpected is a norm that emerges out of the interactions in the system and is more than a sum of its parts. This opens the way to see multiple agents of leadership initiating action and influencing in an intentional way.

• From equilibrium seeking to adaptive striving: CAS are living systems and, by their nature, are adaptive. They amplify feedback loops to help the system continually adapt to fit with the external environment. The interconnectedness of our global economy makes it impossible not to be affected by natural disasters like the earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011. Every affected company, like Toyota or Apple, and all of their supply lines, customers, and shareholders have been impacted by its ripple effects.

• Linear causality to mutually shaping causality: CAS are open to their larger environment and subject to an always-expanding number of variables. Think of a large, beautiful, and complex spiderweb. The web is filled with connections and anything that affects one section will ripple across the web and affect other areas. On a much larger scale, our world is filled with open systems (or webs) that keep interacting with and mutually shaping each other. The mechanistic bureaucratic framework created assembly lines to construct products. Assembly line logic is a perfect example of linear causality, and while linear causality can be created in a closed system, our world isn’t closed. Our political dialogue often reflects simple causality that doesn’t acknowledge the mutually shaping nature of complex adaptive systems. The “drill baby drill” slogan of the 2008 election season would be one example.

One of the new competencies needed for the twenty-first century is to see the integration and connections between multiple systems. The effective leader is one who can create a culture that sees the multiple systems that are in play and pays attention to how they influence each other. Where we used to see leadership as creating a critical mass of support, resources, or power to accomplish results, the current goal is to foster critical connections (Wheatley & Frieze, 2009). This creates a shift in the primary leadership question from “who can make this work?” to “what interactions (connections) will make this work?”

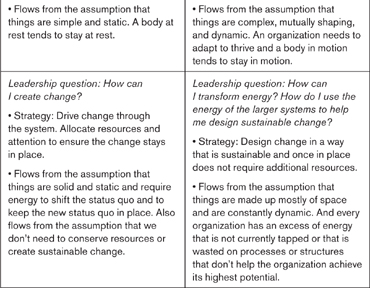

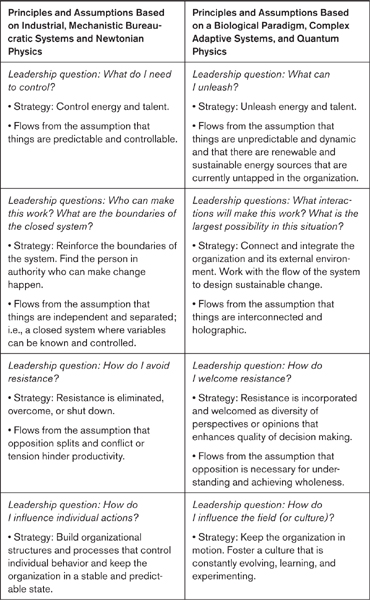

The unrestrained dynamics of open systems makes controlling all variables an outdated myth and an exercise in futility. Effective strategies for influencing change and achieving results require a shift in thinking (Allen & Cherrey, 2000; Olson & Eoyang, 2001), such as asking: “what can I unleash?” rather than “what do I need to control?” (see Table 5.1). For example, a domestic violence agency’s usual approach was to see its clients as victims and the staff’s role as meeting the clients’ needs for safety. But then its leaders looked at everyone in the organization, clients and staff, as part of a whole system and asked what resource was being underutilized or ignored. They noticed the interactions among the women in the shelter and discovered that women were helping each other in their own healing and journey. This led to a more intentional change that was designed around the question, “how do we unleash the energy and talents of the women in the shelter to help in their recovery?”

Table 5.1 New Questions for Twenty-First-Century Leadership

Dancing on a Slippery Floor: A Metaphor for Leading in the Twenty-First Century

Leading effectively today is not only about the questions we ask. It is also about our emotional stance toward the challenges we face. About twenty years ago I was walking down a newly waxed floor at the UCLA campus, where I witnessed a tableau that helped me know how the way I think about things affects how I experience them. Ahead of me were a mother and daughter. The mother was in high heels and walking tentatively down the hallway, holding onto the wall in fear of falling. The daughter, on the other hand, didn’t see danger—she saw fun. She backed up and started running toward the end of the hallway. When she got up speed, she slid the rest of the way. Where the mother saw danger, her daughter saw opportunity.

In 2009 the nonprofit sector hunkered down to ride out the recession. The primary strategy was to conserve, cut, and try to stay alive. Like the woman walking down the highly waxed hallway, most nonprofits were afraid of falling. So they held on tight to their organizational thinking and structures.

A few leaders chose a different path. One was a new president of a settlement house in St. Paul. He saw opportunity instead of fear and decided to use the tensions and difficulties to trigger the evolution of the agency. Despite needing to reduce the staff by one-third, he unleashed talent and energy at all levels of the organization and invested in the organizational culture. He also attracted new talent to the fund development department, which cultivated individual donors to help fill the financial gap left by the changing economy. He hired me to help with the culture work to shift the organization from a top-down, leader-led, bureaucratic, low-risk, highly centralized, controlled organization to a horizontal, leader-full outfit that engaged many members to help redesign the organization, its processes, and even its strategic plan. Work teams cocreated new processes in finance, HR, grants management, facilities, and so on. He didn’t lead or attend these work team meetings; instead, he created a container for them to occur and provided simple attractors to the groups. The function of these attractors was to simplify, increase transparency, engage and involve different people with different ideas (instead of the usual suspects), involve others in decisions that affected them, and move toward implementation. He modeled experimentation and made it known that informed experimentation and innovation were needed to help the organization thrive.

A culture of innovation quickly emerged. The organization became known for emergent practice, and funders were attracted to the innovations and impact they were having. A 2011 culture audit showed a staff that was excited and engaged in working in a mission-focused organization that was doing things that mattered in their community. Like the little girl, this organization decided to start running so it could get a good slide on the slippery floor.

Leading in the twenty-first century is like dancing (or sliding) on a slippery floor. If you try to stay in control, your energy will be focused on not falling. But if you relax and use the wax on the floor to facilitate your dance moves, it will be a lot more fun and effective.

Kathleen Allen, PhD, is president of Allen & Associates, which specializes in leadership coaching and organizational change work. She has written and presented widely on topics related to leadership, human development, and organizational development. Dr. Allen has coauthored Systemic Leadership: Enriching the Meaning of Our Work, written many articles, and contributed to a variety of monographs and books over the years. She is a contributing author of Leadership Reconsidered: Engaging Higher Education in Social Change (2000). She is a skilled facilitator who helps organizations achieve long-term sustainable change. For more information, go to http://www.kathleenallen.net.