3

X Factor

Character cannot be developed in ease and quiet. Only through experience of trial and suffering can the soul be strengthened, ambition inspired, and success achieved.

HELEN KELLER

Getting Fired Is Not the Worst Thing

When Doug Conant who later became CEO of Campbell Soup Company was a young executive in his mid-thirties, the division he was working for was spun off. “The new owners came in and decided to eliminate layers of management. In no time I had lost my job. It was an incredibly humbling experience. I was fired in an awkward way. I was devastated and I was bitter … I went home to my wife, my two small children, and my one very large mortgage feeling every bit the victim.”

Conant was not the type to give up easily. “I’ve always believed that if the new owners had wanted to they could have found an opportunity for me, even with the downsizing. They were not particularly invested in my job search. They said, ‘Well, you will find another job.’ Easy for them to say.”

Help is there if we look for it. “The one thing they did that was truly helpful to me was to send me to an executive search person who ultimately became my mentor. He was the one who introduced me to the true meaning behind the words, ‘How can I help?’ He challenged me to turn the coin over and make the best of a difficult situation. Under his coaching, I was able to move beyond feeling like a victim, to a place where I was proactively advancing my career.”

Inspiration comes in different places. “I’ve always enjoyed reading Louis L’Amour western novels. And in one of his books he had a quote from one of the main characters, ‘he never knew when he was licked, so he never was.’ That quote inspired the mind-set I learned to bring to my work. If I never felt licked, I really never was. And so I picked myself up and [my executive outplacement counselor] challenged me to run the world’s best job search and to pour my energy into that endeavor. I did and it was painful, but productive. It set the table for me to have a good career run after clearly experiencing the most painful job search of my life.”

Breakthrough After Breakdown

Mark Goulston is a psychiatrist by training as well as practice. He is also successful executive coach. He appears regularly on television and speaks to thousands in his keynotes and reaches millions through his writing. But his life was not without adversity. “My greatest personal accomplishment over adversity was that I dropped out of medical school twice and finished. I think I was an untreated case of depression and ADHD and the second time I asked for a medical leave, the dean of the school advised the Promotions Committee to ask me to withdraw (since I was passing all my classes), which was a euphemism for being kicked out.I was at a low point in my life and not able to think very clearly nor able to see any value or future for me.”

Fortunately others noticed Mark’s plight. “At that point the dean of students, William McNary (Mac), stepped in, and pulled me aside. He believed in me when I couldn’t, saw value in me that I didn’t, and saw a future for me that I couldn’t. The most compelling thing he said to me—and my coming from a rather stern, critical, and negative upbringing you’ll truly appreciate it—was, “Mark, even if you don’t become a doctor and don’t even do much with your life, I’d still be proud to know you, because you have goodness and kindness in you and you have no idea how much the world needs that, and you won’t know it until you are thirty-five. The trick is that you have to make it to thirty-five. And one last thing, Mark, and look at me, ‘You deserve to be on this planet. Do you understand me?’ ”

Mark did understand and suddenly Dr. McNary went to bat for him. “Mac appealed my request, which was granted. I went on to do a medical elective at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka and discovered that I could reach schizophrenic farm boys at their Topeka State Hospital, much the way Mac had reached me.”

Mark is one who believes in giving back. “And that has been my life’s work ever since and what caused me, thirty years after the predicted age of thirty-five, to cofound Heartfelt Leadership where our mission is Daring to Care, just as Mac had done for me.”

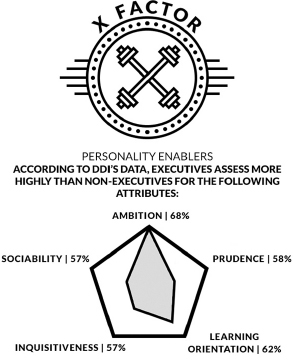

SOURECE: DEVELOPMENTAL DIMENSIONS INTERNATIONAL, INC. 20131

X Factor. Each of us has a unique set of talents and skills that we use to make our way in the world. More than just talent, it includes what makes you—your character, convictions, and personal beliefs. Consider this set the X factor: what enables you to do what you do and do it well. Put simply, X factors form the “right stuff of leadership.”

The ultimate measure of a leader’s legacy is the effectiveness of her ability to change the situation and leave things in better shape than she found them. If that is the criterion, then certainly Margaret Thatcher stands as a leader to be remembered.

Margaret Thatcher

When Thatcher became prime minister of the United Kingdom in 1979, the country was in turmoil. Many lamented the once proud nation’s fall from status. The economy was weak, the trade unions were holding businesses hostage, and arcane rules and regulations hamstrung businesses and threatened the survival of many.

By the time she left office in 1990, the face of Britain had changed. As Alistair MacDonald put in his remembrance of Thatcher for the Wall Street Journal, the prime minister was known “for her role in revolutionizing the failing economy”—a process that caused great “social change and division”—as well as for Britain’s victory in the Falklands War. “We have ceased to be,” Thatcher said after the war,” a nation in retreat.”

Indeed, retreat was not a word in her vocabulary. “I came to office with one deliberate intent. To change Britain from a dependent to a self-reliant society, from a give-it-to-me to a do-it-yourself nation.”

Facing challenge was nothing new to her. Born Margaret Roberts, she attended Oxford and became a research chemist. But politics was in her blood, due in no small part to the influence of her father, Alfred Roberts, who served as mayor of Grantham. He was a grocer, a small businessman, and a Methodist minister who valued free enterprise and gravitated to the Conservative Party.

Margaret Roberts aspired to political office but when she was coming of age in the 1950s, politics in Britain was considered a man’s purview. She appealed to party elders for the opportunity to run as the Conservative Party candidate but was turned down. When she finally did earn a spot on the ticket she was defeated twice. By then she had married Denis Thatcher, a globe-trotting oilman, and was the mother of twins, Carol and Mark. She had resigned herself to the idea that elected office was not for her. But when a seat in Finchley, a suburb of London, opened up, she ran and won.

Arriving in Parliament in 1959, she met with resistance and even outright hostility from her male colleagues. Famously, she and Ted Heath, who would later serve as prime minister, were rivals. She would eventually replace him as the leader of the Conservative Party.

Coming to Power

After serving as party leader, Thatcher led the Tories to election victory in 1979 after a winter of national strikes. During her first two years, levels of unemployment rose and the economy shrank. Her prescription was free-market economics, in contrast to the Keynesian model Britain had followed for decades. She was met with stiff resistance, to which she exclaimed, “I am not here to be liked.” In time, her measures worked, but the bitterness of those who opposed her remained strong.

Opposition was particularly strong in Northern Ireland. The situation in Northern Ireland had escalated into more terrorism, which at times spread to England and in fact took the life of Airey Neave, one of Thatcher’s closest colleagues, prior to her becoming prime minister. At a party conference in 1984 in Brighton, the wife of one of her ministers was killed in a bomb blast and thirty others were injured. The IRA claimed responsibility. Part of the hostility was her refusal to recognize IRA prisoners as political and therefore exempt from regulations governing criminals. IRA prisoners went on a hunger strike and ten died.

She deserves partial credit for opening relations with the Soviet Union. Having met Mikhail Gorbachev before he became president, she noted that he was one with whom “she could do business.” She relayed her thoughts to her good friend Ronald Reagan and urged him to reach out to Gorbachev, which he did several times in face-to-face meetings in Geneva and Reykjavík. Upon her death Gorbachev said, “[W]e managed to achieve mutual understanding, and this was a contribution to the changing atmosphere between our country and the West, and to the end of the Cold War.”

Margaret Thatcher was a divisive figure. Opponents on the Left disliked her intensely and in fact she helped unite opposition. Her heavy-handed management style also rubbed her Conservative Party colleagues roughly. When, in the end, she was forced from office in what amounted to a party coup, Thatcher shed tears but likely her colleagues shed few. She maintained her equilibrium after someone complained to her that she had been done in by colleagues. “We’re in politics, dear,” she said.

It’s true enough that Thatcher was forced from office by her own party, which had grown tired of her strident management style and her headstrong ways. Yet she had changed the face of Britain, and the prosperity of the 1990s was due in large part to her leadership. She was known as the “Iron Lady,” a name that she heartily embraced because it captured her sense of self and her resolute sense of determination.

Twilight Years

Shortly after leaving office in November 1990, Thatcher was elevated to the House of Lords and became known as Baroness Thatcher. She also devoted time to her foundation and occasionally commented on international affairs. In the early 2000s, according to her daughter, Carol, Thatcher was afflicted with dementia, something that was vividly depicted in the movie The Iron Lady starring Meryl Streep as Thatcher.

While she could be prickly, she maintained her sense of humor. As MacDonald noted, in 2007 when a bronze statue of her was unveiled in Parliament, she said, “I might have preferred iron, but bronze will do.”

After her death, John Burns, a British national who works for the New York Times, summed up her legacy on PBS News Hour by saying, “The Britain I grew up in, in the wake of the Second World War, was a country which was in precipitous decline, which had entirely lost its national self-confidence. And Mrs. Thatcher put that right.”

Thatcher serves as a lesson in perseverance. She held to her ideals and in doing so opened Britain to become a more prosperous nation as well as one respected for its fortitude and resilience.2

*****

Margaret Thatcher had the skills to succeed as a politician and prime minister but perhaps her greatest attribute was her personal determination. It is one of our X factors, attributes that are essential to your ability to take charge of your life as well as to radiate the authority you need to bring others together for common purpose.

X factors are integral to leadership because they provide the backbone a leader needs to stand up and be counted, as well as the ability to do so with grace and dignity. Leaders are always on. The higher their profile, the bigger the stage; their words and actions are magnified by the outsize roles they hold. That is, a word from a CEO or commander rings with importance, but it also carries significance. Such leaders hold power over others, and therefore what they do is of consequence. Those in power who abuse their position lose the faith and trust of followers; those who work hard at their jobs and try to do the right thing gain influence. People want to follow them because they trust them.

A case in point is provided by General John Allen when he served as the commander of NATO forces in Afghanistan from 2011 to 2013. He went to Afghanistan to begin the long process of handing military authority over to the Afghan forces that coalition troops were training. What he did not need were distractions, but, as every leader knows, heads of organizations rarely have the luxury of choosing issues. They must deal with the situation at hand, whatever comes their way. One crisis that Allen faced, which threatened to put the entire mission at risk, was the accidental burning of Korans at Bagram Airfield. Having spent much time in the Middle East, living in Muslim cultures, Allen knew that this situation was very serious. After all, this Koran burning came a year after the deliberate burning of a Koran by the provocateur Reverend Terry Jones in Florida, which was viewed by Muslims as an affront to their faith. Some, specifically the Taliban, would also seek to exploit the incident as an excuse for violence, and sadly it occurred.

As Allen explains: “So I believed that this could have conceivably been the end of the campaign. And so as I reached out across the entire command to grip the unfolding crisis that we were facing across all of Afghanistan, I was on two or three occasions every day speaking to all of my commanders, ensuring that they were calm on the process, engaging with their counterparts. We were in gun battles, not just with the Taliban, who was trying to leverage this crisis to their advantage to prove that we, ‘the crusaders and the Jews,’ as they called us, were in fact a cancer inside their society.

“So we were fighting the Taliban more intensively and we were now facing substantial and intense rioting around the country. And in doing that we successfully dealt with those crises across the entire country over a span of about six days. It was an unrelenting six days. It was six days of … moving from spot to spot trying to put out some really substantial potential crises where troops might have been in a gun battle or [where] we had casualties.” Allen also got involved in recovering “the bodies of a couple of my officers who were killed in the Ministry of Interior.”

How a leader invests himself and spends his time during a crisis is critical. As Allen explains, he was leading up—keeping his senior U.S. and NATO commanders, as well as the president, informed. He was also leading horizontally with President Hamid Karzai, “spending a great deal of time with President Karzai and his leadership to help him help himself and help him help me by keeping his rhetoric measured to keep this from flying out of control with the Afghan public.”

Allen was also spending much time with his commanders. Moment to moment, Allen had to decide where his physical presence would be of the most value. As he says, that comes with experience as a commander. In addition to the application of fires and maneuver, the sustainment of the force, and critically, the commitment of the reserve, “one of the most important functions of a commander is how he or she uses their time and how he or she in the end maneuvers the presence of the commander to have the greatest possible moral effect at key points and times in the crisis.”

Allen was not only engaged on the ground, he was linked via satellite to commanders back in the United States. As Allen explains, “My personal presence pervasively on the video teleconferences with my commanders a couple of times a day—and my personal presence at the moment of crisis around the country—went a long way toward keeping everybody calm and reacting to the crisis the way I wanted them to.”

Few leaders will face the kind of mayhem that Allen did, but every leader will face crises that demand the best response possible. As Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips, notes, “Strong leaders must be resilient.” This is particularly true in the oil and gas business, which operates in a commodity market subject to wild swings in price and to boom-and-bust cycles. The business also requires a measure of guts to take its inherent risks. When it comes to exploration, “We only expect to succeed once in every three or four attempts we take to drill a conventional exploratory wildcat well.”

Not only must leaders be resilient, they must project that spirit. Lance observes, “You have to trust the strategic direction you’re pursuing and the objectives that you’ve set, because you’ll always get a few curve balls that’ll test your mettle and challenge the direction you’re trying to take the company. You’ve got to keep your eye on the ball—being mindful of what the short-term environment is throwing at you, while also being consistent with the objectives you’ve laid out.”

Leaders must provide clarity for people in the organization, freeing them from issues “they don’t need to worry about, and instead letting the senior leaders worry about them,” says Lance. “While the world is uncertain and changing around you, the leader must keep the team focused in the right direction. Attention shifts to specific tasks that are aligned with the goals we need to accomplish and milestones we need to reach. Those are the things that best motivate a team and keep them focused on the task at hand.”

Such crises may run the gamut from a product recall, factory closing, or workplace fatality to day-to-day challenges that escalate. In those instances, leaders will need to call upon all the reserves they have—their X factors—not simply to survive but to hold their people and their organizations together under great adversity. Perseverance backed by determination does not come from thin air; it emerges from the character and convictions of those in charge.

It is essential to consider factors in addition to self-awareness that help personal growth. According to the 2013 Time Creativity Poll, those surveyed rated the following as the characteristics they most valued in others:

- 94 percent identified creativity

- 93 percent rated intelligence

- 92 percent said compassion

- 89 percent said humor

- 88 percent said ambition

Let’s explore these attributes one by one.

Creativity

According to the Time survey, 71 percent of respondents said that both nature and nurture were factors in fostering creativity. Fifty-eight percent said it emerged from sudden inspiration while 32 percent thought that it occurred over time. Fifty percent of those surveyed said creative thoughts came to them in the form of pictures, while 34 percent formed their ideas in words.

Thirty-five percent of those surveyed said that the United States was the leader in creativity, compared with 23 percent who said China was the leader and only 19 percent who named Japan. For those who believed that America was not the leader—a majority of those surveyed—31 percent attributed the problem to schools, 30 percent to government, and only 17 percent to business. In fact, 55 percent of respondents said that technology is helping Americans be more creative versus 32 percent who said technology was hindering it. Bottom line, 62 percent of those surveyed said that “Creativity is more important to success in the workplace than they anticipated it would be when they were in school.”3

Clearly, creativity is valued, and if organizations do not do enough, then it is up to individuals to develop it in themselves.

Intelligence

No leader can achieve much if he is lacking smarts. Intelligence is the raw horsepower needed to process information and make sense of it. And while processing power is highest in young people, the ability to apply it—knowledge—comes with experience. Intelligence is the baseline for competence. If an individual lacks the mental horsepower to do the job, then she will have little chance of succeeding.

It would be a mistake, however, to restrict intelligence to verbal and mathematical abilities alone. Harvard professor, psychologist, and best-selling author Howard Gardner has championed the cause of multiple intelligences. The multiple dimensions include spatial and kinetic, necessary for athletes; rhythmic, necessary for musicians; and interpersonal, vital for forming relationships, among others. Gardner has even made a case for existential or moral intelligence. The definition of morality is up to the individual; it may be put into practice through religious belief and practice, or it could be another form of mindfulness.4

Implementation of one’s own capacity for multiple intelligences is essential to a leader’s ability to lead. The awareness that you have the capacity to employ more than cognition to your leadership broadens your ability to think creatively, solve problems, and connect with others.

Compassion

Leadership literature is full of articles, even books, on the power of passion. While passion is essential to success at work—you need to love what you do—compassion is the element, as the Time survey shows, that others value. People want to know that their leaders care.

Compassion is a virtue rooted in the dignity of the individual. When you extend concern and offer care, you are saying that the person is worth it, and you want to do something to help. And it’s the small things that matter.

Compassion takes many forms. We see it when employees pitch in to help a colleague in need. Sometimes the aid takes the form of a donation for a medical expense or hardship. Other times we see coworkers offer a fellow employee assistance by cleaning his house or shopping for groceries. And very often if an employee is out, her coworkers will band together to cover for the individual to make certain the work is done on time.

Humor

Life is hard and work is tough. Truisms, yes, but no less relevant in our daily lives! So when people can find laughter, it is something to be valued. Humor adds richness to our daily lives. Those who can look at a situation—whether at work, at home, or at play—and find humor are those we like to be around.

Every spring, a group of my friends (who all hail from Michigan) take a trip south to play golf. None of us excels at the game in the truest sense, and what brings us together is not the game but rather the camaraderie. Laughter is the stimulus that nurtures that camaraderie. We take pleasure in joshing one another and we roll in laughter like fifteen-year-olds at stupid jokes that one or another of us says. What I remember from these trips is not the golf courses or the accommodations or even the food, which are all good. I remember the spirit of levity that we share when we are together.

Having a sense of humor is a good attribute for a leader to possess. This is especially true when the leader turns the humor on himself. A leader who can laugh at his mistakes and poke fun at himself is one who is confident in his abilities and at the same time projects a sense of humanity and fun that draws people to him.

Humor is the great lubricant. It is a way to facilitate conversation and put people at ease. A master of this technique was Franklin Roosevelt, who projected a sunny persona; it complemented his sense of optimism. He also delighted in puncturing the egos of people in power, those who thought themselves better than the rest of us. Although a patrician by birth, Roosevelt as president knew how to speak to the common man, and at times his humor made him seem one of us. That was a secret to his ability to connect well with the American public.

Beware, however, of turning humor on others. Put-down humor can erode another’s self-confidence, especially if the jokester is the boss. That has a debilitating effect on the subordinate’s belief in himself. Others, too, pick up on the theme and look less favorably on the individual, even pitying him. That’s deadly.

Ambition

While the Time survey ranked ambition a bit lower than other attributes (88 percent, compared with other attributes rated over 90 percent), one factor in its lower ranking may be that this survey measured attributes valued in others. Some of us may not like ambition in others, because we perceive highly ambitious people as overbearing or obnoxious. And while ambitious people can grate on us at times, ambition is an essential component in personal drive. Ambition sparks our internal motivators, it fuels our get-up-and-go, and it prompts us to tackle the challenges of the day.

Women in executive positions often face a backlash on the ambition dimension. There’s a game I sometimes use in teaching in which I ask the group to describe a male executive who is hard-charging and aggressive. Such a person is often described as aggressive, but in a good way. A female executive, by contrast, might be described as “hell on wheels,” and that’s not a compliment.

Ambitious women need to project a softer edge while ambitious men can get away with being career driven. It is not fair, and it results in too many women hiding their abilities so they will not appear “too ambitious.” Sadly, we need leaders who are bold as well as assertive. Ambition focuses energy on career goals, but it also provides a stimulus for action and execution.

Curiosity

While curiosity was not mentioned in the Time survey, many leaders value it and look for it in others. According to Ryan Lance, a curious leader is one who is trying to figure out why things are what they are. Jim Haudan, CEO of Root, says curiosity “is an insatiable desire to understand and to ask and to pursue and to question and to answer. Show me somebody who’s curious and a lifelong learner and I’ll show you somebody we can train in any way necessary to be successful in our business.”

A curious leader is forever asking questions. She does this as a means of discovery, of provoking thought. A curious leader is one who is looking to find possibilities where others may have overlooked them. As Haudan notes, humility complements curiosity. A humble leader admits she does not have all the answers and is patient when explaining things to others, especially those who may not understand the concept the first time. Haudan says, “A humble leader meets people where they are at the moment. Not where he or she expects or wants them to be. [These leaders] actively try to understand what it is like ‘not to know’ so they can translate the complex language of strategy into a common language of shared meaning.”

Curiosity is a powerful catalyst for leaders seeking to make positive change. Questions serve as ignition for exploration. A curious leader does not expect a single answer but rather an exploration of possibilities that can lead to new discoveries as well as new solutions.

Character

As important as the preceding attributes are, none is more important than character. It is the foundation upon which an individual and, certainly, leaders stand. Without it an individual lacks backbone. One of the best definitions of character I have encountered comes from Jeff Nelson, who established the OneGoal program in Chicago, which focuses on helping young people from disadvantaged backgrounds succeed in high school and later in college. The elements of character, as Nelson sees it, emerge from five aspects: integrity, resilience, resourcefulness, professionalism, and the one we just discussed—ambition.

For a column in Forbes.com, I put these attributes in the form of questions that leaders need to ask themselves. Here they are.5

- How do I manifest integrity? Do I pay lip service, or do I live it even when it means making a sacrifice?

- How do I demonstrate resilience? When our team faces an obstacle, what example do I set for them?

- How resourceful can I be? When we are faced with limited resources, what do I do to help my team make the best of the circumstances?

- Do I act my role as a true professional? Do I keep myself educated in my field, stay up-to-date on trends, and act on behalf of my team?

- Is my ambition working for me or against me? That is, does my quest for success inhibit my ability to work well with colleagues and to collaborate with them?

Such questions provoke thoughts about the character we exhibit to others. After all, leadership, as is often noted, is about perception—how our followers perceive us. Leaders also invest themselves and their hopes in the character of others. Chester Elton tells a story about his former boss, Kent Murdock, who was the CEO of O.C. Tanner, where Elton worked for nearly two decades. As Elton puts it, Murdock was always great about saying, “ ‘Place your bet on character.’ And so when Adrian [Gostick] and I were writing these books and we’d come up to different obstacles or tough things he’d always pull us aside and say, ‘Don’t worry about perception and what people are saying. I’ve bet on your character, and you’re both of high character. You’ll figure it out.’ ” It was brilliant, says Elton. “Kent challenged us to solve the problems but basically what he was saying was you’ve got my support. We never wanted to let him down. We knew he believed in us. And in turn we believed in him.”

Fernando Aguirre, who served as CEO of Chiquita Brands, spent the first part of his career at Procter & Gamble (P&G). He credits P&G with teaching him how to hire for character. “We all can teach and train and learn functional skills. But I think having the right character, having the right attitude in your DNA, is even more important than skills.” With younger people, identifying character comes from looking at their experience at school as well as in other activities such as sports, the arts, or the community.

When hiring executives, Aguirre says he learned to discern character by listening to candidates talk about their job experiences. If they speak negatively of previous employers and supervisors, it’s a warning sign that the individual is not a team player. He says, “You can ask enough questions to draw people out like that. I typically interview people for an hour and if I liked them I’d stay an hour and a half or two …” Later, he’d take them to lunch or dinner. “I would see their habits … and how they conducted themselves,” Aguirre says. Not everyone made it to mealtime. As he notes, “I had interviews where, after twenty-five minutes, I said, ‘All right. Thanks for coming.’ And my assistant would know right away that this candidate was not getting hired.”

Character becomes the person, but it does not exist in a vacuum. We see it manifest in attributes that support it. Consider the next few attributes.

Resilience

There is no shame in getting knocked down. It is what you do next that matters most. One man who knows what it is like to be pushed to the limits is General John Allen, a veteran of multiple combat tours. Here’s how he describes a moment of truth he experienced in Iraq at the outset of what became known as the Anbar Awakening.

I remember on one particular occasion we had a really bad day in and around Fallujah, and I got back to my command post and sat down. The temperature was just scorching hot. And I sat down on the steps in front of the space [individual living quarters] in which I lived. It was an old beat-up Iraqi command post. It was now our command post. It was pretty good living, actually, by marine standards, but it wasn’t much to look at. So I sat down on the steps outside of this building and we were exhausted and the temperature was blistering hot and, of course, we were still in Humvees at the time, we weren’t yet in the MRAPS [Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles], which were much more protected.

The temperature in Humvees could get up to 135 or 140 degrees pretty easily. We had a really bad day and we’d taken a lot of casualties across Al Anbar, and I remember sitting there on the steps with my head in my hands and my helmet was off to my side. I think it was on my right-hand side. It was upside down so it was laying on its top and my M4 carbine, my rifle, was across my helmet. And I’m sitting there thinking my God, I’m a general officer in what’s appearing to become a lost cause. I’m gonna be part of losing a war. And then suddenly I looked—I opened my eyes and I looked down and blood was just flowing from my nose. The whole business, the temperature, the environment, the pressure was such that the capillaries in my nose had opened up and there was this puddle of blood down between my feet. I thought to myself, I can’t let this be the moment where I decide to give up. This has got to be one of those moments, a point in history, where I decide I’ve got to reach down inside me and turn this around.

Allen persisted. He carried out his mission and, as a result of efforts like his and that of thousands of other marines and army soldiers, the tide of war turned in 2007, in what became known as the Anbar Awakening. Anbar was supported by “the surge,” an effort that allowed a measure of peace in Iraq and the eventual withdrawal of coalition forces from Iraq.

Courage

Many leaders have noted that courage is not the absence of fear, but rather the management of it. John Kennedy, who severely injured his back and lost his boat in the South Pacific in World War II, believed that courage was something to be endured. “The courage of life,” wrote Kennedy, “is often a less dramatic spectacle than the courage of a final moment; but it is no less a magnificent mixture of triumph and tragedy. A man does what he must—in spite of personal consequences, in spite of obstacles and dangers and pressures—and that is the basis of all morality.”

To my way of thinking, Kennedy’s definition is closer to the reality that many of us face—outside of harm’s way. Courage for us means choosing a moral path: putting what’s right ahead of what’s expedient. In that regard, we make choices to stand by our convictions and in the process make sacrifices that may initially hurt us, but in the long run instill character. True leaders also exert courage in service of others. They put themselves on the line in order to advance the career of a subordinate or even save the jobs of others by sacrificing part of their compensation so that one, two, or even more can hold their jobs in tough economic times. Courage comes in many forms and is integral to the ability to lead others.

Confidence

All of the factors we’ve discussed thus far are essential to individual development, but there is one additional X factor that is essential to bringing all of these attributes to bear in constructive ways. It is confidence. A leader without confidence is like a boat without a rudder, drifting aimlessly. There are many ways to think of confidence, but I like to think of it as the internal spirit of “can do.” It emerges from within us all.

Confidence emerges from our accomplishments. It arises from what we have done and what we have learned, so that when we face the next challenge we have a reservoir of something inside of us that says, “Yes, I can do this.” Consider confidence as a muscle. When you are first starting your career, that muscle may be underdeveloped. But with everything you accomplish, that muscle gets a little bit stronger; it even gets stronger with endeavors that do not go so well.

As much as confidence is internal, it has two external applications. When you are confident in yourself, others sense it, and, when coupled with what you have done well, they come to believe in it. Their sense of confidence in you reflects positively on you and adds to your confidence in yourself.

There is a third aspect to confidence, and that comes when you are able to instill it in others. I recall something that Kenneth Duberstein, who once served as chief of staff to President Ronald Reagan, said about the former president. He asserted that one of Reagan’s gifts as a politician was the ability to get people to believe in themselves and their own abilities. When people believe in themselves anything is possible.6

Such insight is fundamental to sports coaching. So often a coach’s true job, aside from drawing up plays and getting players to buy into the plan, is getting his team to buy into their collective abilities. That is, if they play together, they will have success. Confidence is an imperative, but individual players must believe in themselves before they can believe in the team.

Of course, there is such a thing as misplaced confidence. Someone who is unaware of how she is perceived by others may fall prey to overconfidence. This individual may not read the signals that others send. Think of Michael Scott in the television comedy The Office. Scott (as played by Steve Carell), is supremely confident in his abilities, but he is so self-absorbed and ill attuned to the feelings of others that he cannot see that they think he’s a buffoon. Such individuals can become overconfident and even arrogant because they don’t see themselves as others do.

Beware of False Gods

As we learned in chapter 1, mindfulness requires practice, but it also requires humility. In this regard, we can look to history for examples of leaders who failed to keep their egos in check. One egregious example was Alexander the Great. After conquering much of what was called the “known world,” Alexander began to think of himself as a god. (In fairness, deities in Greek and Roman times were plentiful, so the line between mortality and immortality—at least in one’s imagination—was not a broad leap, especially for heroic figures.)

Nonetheless, as Quintus Curtius Rufus, a Roman historian, notes in his History of Alexander, the conqueror began acting out, “punishing” those whom he distrusted. As Curtius notes, “Success can change one’s own nature and rarely is anyone cautious enough to respect his own good fortune.” While in Persia, Alexander began expecting subordinates to prostrate themselves before him, a Persian tradition. Later, his army in India rebelled, refusing to go any further. They wanted to go home. There were death plots against him. He died in Babylon, possibly poisoned, though that account is in dispute.

What is not disputed is that Alexander’s ego, like that of many leaders who end up meeting untimely ends, cost him the loyalty of many of his followers. It also damaged his legacy. Little of what he had gained was sustainable by his heirs, and his empire dissipated.7

It takes real effort for a successful leader to keep himself humble. Humility arises from perspective, and part of that perspective arises from knowing one’s own limitations. As Fernando Aguirre puts it, “I realized when I became a CEO that it took me a year or two to learn how to be a CEO, and it’s amazing how you get to those levels. Later on in life you realize that maybe you weren’t as prepared and ready as you probably could have been. A very important aspect of this is you become more aware about the influence you have on others.” Aguirre notes that CEOs of public companies are under tight scrutiny, especially in the era of social media, where behaviors good and bad can go public. Senior leaders are also subject to criticism. “Some people are constructive critics, many people are not,” says Aguirre. “You just have to be aware that whatever you say and do could sometimes work against you. So it is a very important aspect of being a leader, in my opinion. You have to be mindful of yourself and you also have to be mindful of others because you may be impacting other people without knowing about it.”

For one thing, some leaders lack what all good leaders must project: a sense of humility. Humility is a virtue, but in our hypercompetitive world it is something that gets shunted aside. Humility to the uninitiated is a sign of weakness. Just the opposite is true. Humility is a sign of strength. Think of it this way: being confident enough to admit your shortcomings or mistakes does not make you a weakling; it demonstrates that you possess a degree of self-awareness.

Closing Thought: X Factor

The X factors delineated in this chapter are intended as thought starters. As important as they are, you can find other factors that contribute to success, yours and others’. The challenge for you is to find these factors and incorporate them into your leadership persona. Then you can lead in ways that bring people to you, so that together you can achieve intended results.

The sum of your X factor attributes gives you the foundation to do what you do better than anyone else. Your X factor could include a talent, that is, a proclivity for doing something well. Or it could be a skill, like a facility for working with data. Understanding your X factors is essential to your development.

Your X factor attributes are what people will come to know you for and rely upon you for. For example, if you are the kind of person who can get people focused and on task, that will make your reputation. Likewise, you may be a creative type, one who thinks of ideas to make things better.

Find ways to hone your X factor attributes. Look for opportunities to get better at what you do. This may come through on-the-job practice or through further training. You may also need to acquire more skills through additional schooling. Another way to improve your X factor attributes is by taking on new responsibilities. You can do this by becoming a team or project leader. Undertaking such a role will challenge you to expand your skill set, especially as it applies to connecting with others (as we will see in chapter 4).

The sum of a leader’s accomplishments is how she has positively affected the organization. This is a leader’s legacy, and it rests on a foundation of character, ambition, resilience, and perseverance.

X Factors = Right Stuff

Leadership Questions

- What are you doing to capitalize on your X factor attributes?

- What are you doing to apply the talent you have to the skills you possess?

- What can you do to ensure that you keep discovering new opportunities to grow and develop your talents and skills?

Leadership Directives

- Look for ways to focus on putting your character into action. Find ways to assert your inner convictions by setting an example that others want to follow.

- Find opportunities to apply your imagination. Are there tasks you could reduce or eliminate in favor of doing something more efficiently?

- Look for examples of compassion in your community. How are people you respect demonstrating a commitment to others in order to make a positive difference?

- Lighten up. Hard work is, well, hard, but that does not mean you cannot find some humor to ease the situation.

- Ambition fuels your drive. What are you doing to put your ambition into gear? Are you ambitious for the right reasons?

- Confidence is a feeling you get when you reflect on your accomplishments. How are you demonstrating it in the workplace?

- Develop your own X factor list. What is important to you and why?