Introduction to Project Control

Projects help organizations achieve their goals and strategic objectives. For example, 95 percent of government policies in the UK are delivered through major projects (National Audit Office 2013). Put simply, business outcomes are affected by the success of projects. Therefore, project-focused practice is common for many organizations in different industrial sectors, from an oil company developing an exploration site, to an investment bank installing a new IT system; from a technology company developing and launching a new type of gadget, to the government of a country constructing a new high-speed rail infrastructure. One of the distinguishing features of projects is that they are normally required to be completed within specified timeframe, scope, and an allocated cost budget. However, many projects are not delivered successfully, impacting negatively on organizational earnings and profitability. Control is the recognized mechanism to prevent project failure and keep a project on track. Even though the importance of project control during the implementation of projects is obvious, research indicates that many projects still fail from a cost and time performance perspective.

The classic research by Flyvbjerg, Holm, and Buhl (2003) across 20 countries and five continents, showed that nine out of every ten projects encounter cost overrun, indicating this as a global phenomenon. Research by the project management institute (PMI) (2020) revealed that organizations globally wasted an average of $114 million for every $1 billion spent on projects due to poor project performance. This problem is common across various industries in the economy, for example, construction industry: $127 million wasted for every $1 billion spent; energy industry: $113 million wasted for every $1 billion spent; government: $97 million wasted for every $1 billion spent; health care industry: $113 wasted for every $1 billion spent. High-profile examples of projects with such financial wastage include:

• Berlin’s New Brandenburg Airport, which exceeded budget by 41 percent and time by 9 years (O’Neil 2019);

• Denver International Airport: 194 percent over budget and 1.3 years late (Jergeas and Ruwanpura 2010);

• Scottish Parliament: £400 million over budget and 3 years late (Flyvbjerg 2017; O’Neil 2019);

• Crossrail: £4 billion over budget and 3.5 years late (Reuters 2022).

So, what’s the answer to avoid situations like the above? Poor performance and financial waste in projects can be avoided by setting up a well-designed and intelligent project control process, supported by good practices and the right culture that will enable projects to be delivered more successfully. Research by Pollack and Adler (2016) showed that organizations with effective project management skills have a 75.5 percent chance of increase in profitability compared with organizations without them. But if project controls are not carried out consistently and designed intelligently, they won’t be effective. Furthermore, control is one of the major tools of project management. It has been stated by the Association for Project Management (APM) (2015) that “effective project management requires effective control.” Project control involves measuring progress constantly, evaluating plans, and taking corrective actions when required. In essence, project control is the application of processes to measure project performance against the project plan, to enable variances, to be identified and corrected, so that project objectives are achieved (APM 2010) including keeping projects on track and within budget. But this is easier said than done. Establishing and following effective project control is a multifaceted, sometimes complex process, which is often not done consistently within organizations.

Traditionally, as argued by Sanchez, Terlizzi, and Moraes (2017), the inherent task of successful project management has been to deliver the outputs of the project on time, within the budget, and to the required scope. Which has led these three areas (cost, time, and scope) to stand out when it comes to control. Time control, also often referred to as schedule control, is the aspect of project management that involves the management of the time spent and progress made on project tasks and activities with the aim of completing the project on time. Cost control involves the management and technical procedures used to manage the delivery of a project within the planned budget, whereas scope control is the process of managing the project’s outputs and changes to the outputs to enable delivery of what was agreed.

Effective project control helps save costs and improve return on investment. When deployed consistently using good practices, project control can increase management’s visibility of the financial performance of the projects to allow for the development of mitigation plans to improve the performance of poor performing projects. Effective project control also makes it easier to predict how long projects will take and how much they’ll cost, reduce costs, improve company margins, and provide organizations with a competitive advantage over organizations with less mature project control capabilities.

Introduction to the Process of Project Control

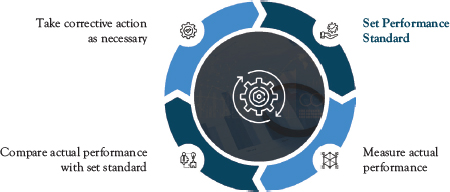

The objectives of a project such as delivery at the required time, scope, and budget will be difficult to achieve unless the project is controlled. This is because delivery of projects does not always go perfectly to plan, which reflects the popular military saying attributed to the Prussian military leader of the 19th century, Helmuth von Moltke, that no plan survives contact with the enemy. Therefore, projects require a process for monitoring and managing in such a way that deviations from plan are detected and corrected timely. In practice, project control is an iterative process that is usually achieved in three phases: setting performance standards, comparing actual performance with these standards, and then taking necessary corrective actions. In a project environment, project control normally involves three operating modes: (1) measuring, which is determining progress by formal and informal reporting; (2) evaluating, which is determining the cause of deviations from the plan; (3) correcting, which is taking actions to put right any deviation from the plan. In essence, controlling the project involves the process of managing the many problems that arise during project execution to maintain the plan. The process of project control at its simplest form is depicted in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The basic process of project control

The key components of the process involve setting performance standards, performance measurement, comparison against the set standard, and corrective action. These are briefly explained below. However, a more detailed explanation is provided in Chapter 2 and referred to all through this book.

• Setting project performance standards: Targets are set for each project activity in terms of time, cost, quality, and so on. The plan for the project is used to set these standards, which then serve as the standards that are used to control the project.

• Performance measurement: This involves the measurement of the actual performance of each project activity as the project progresses to get feedback on how each activity is being performed and the performance of the whole project.

• Comparison against the set performance standard: During this process, the result of the actual performance measured is compared with the project standards set in the plan to determine deviation for each activity. This process also involves the analysis of the causes and prevalence of the deviations.

• Take corrective actions: If comparison and analysis indicate that the activities are deviating from the plan, corrective actions are then taken to improve the situation so that the activities can be brought back in line with the project plan. This part of the process is the crux of project control as it seeks to resolve any identified problem to get the project back on track.

Reasons for Embarking on Project Control in Practice

The main reason for the utilization of project control cannot be more obvious—it is to prevent cost overrun and delay (time overrun) of projects. Other reasons project management practitioners utilize project controls include:

• To ensure that the project progresses in an orderly manner;

• To enable efficient use of resources;

• To provide and/or obtain information and knowledge of the status of the project;

• Good management practice and part of a company’s quality procedure;

• To provide more value to the client leading to client’s satisfaction and repeat business.

The above reasons for embarking on project control in addition to the need to prevent project cost and time overrun are all geared at achieving the ultimate objective of the execution phase of a project, that is, to enable successful project performance. The performance of a project is normally measured in terms of one or more project objectives agreed at project inception. It is important to note that despite many objectives that a project may be subject to, the classical project performance objectives remain completing the project on time, to the required scope, and within budget. This is often referred to as the “iron triangle” or “triple constraint” (this is explained further in Chapter 2). It is therefore imperative to control these objectives during project delivery so that they are always in congruence with the plan to enable project delivery success.

When Has a Project Performed Successfully?

Traditionally, a project is considered successful if it is delivered on time, at the stated cost and quality/scope, and provides the client with a high level of satisfaction. Therefore, project success performance has usually been measured using factors related to budget, quality, and schedule (time) performance. For example, in measuring cost and time performance, two parameters are often used: cost growth and time growth. Cost growth is a measure of performance of cost control, that is, the final project cost divided by the initial project cost. While time growth is a measure of the performance of the project time plan, that is, the final project duration divided by initial project duration.

Despite a consensus that cost, time, and scope (including quality) are the key success criteria for projects, many commentators have argued that other factors should be considered in addition to them. For example, Davis (2014) stated that project success should also be viewed in relation to the perception of the project’s stakeholders. Therefore, customer satisfaction is now often considered as a key project success criterion as Anantatmula and Rad (2018) have observed. Furthermore, the socioeconomic impact of projects has also broadened the project success metrics as stated by Zaman, Florez-Perez, Khwaja, Abbasi, and Qureshi (2021).

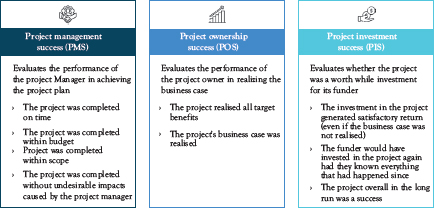

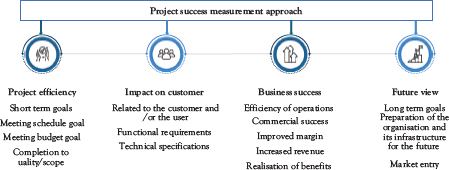

It is now perfectly acceptable, as Camilleri (2016) argued, to assert that success is subjective and varies according to the assessor and thus requires a more comprehensive set of criteria to encompass various views and interests (see Figure 1.2). Therefore, a distinction between project management success and project success is also often made. With the argument being that project management success is measured against the traditional success criteria of time, cost, and quality/scope while project success tends to be measured at a more strategic level by comparing the outcome to the overall project objectives.

Figure 1.2 Example of a multistakeholder view of project success

Source: Zwikael and Meridith, 2021

For instance, Lock (2013) pointed out the three objectives of time, cost, and quality might be mostly related to the interests of the project manager, project team, and contracting parties delivering the work; however, other stakeholders might be more concerned in other success measures such as delivering business value, operational benefits, customer satisfaction, strategic impact, and so on. The Sydney Opera House is an example that is commonly used to prove that the triple constraints of time, cost, and quality do not epitomize entirely the true meaning of project success. This project was completed at 1,300 percent above the original budget and took 10 years longer than planned to construct! However, it is considered one of the most popular tourist attractions in the world, attracting more than 10.9 million people a year (it has been added to UNESCO’s world heritage list). It has continued to generate huge revenue for its investors with the landmark becoming not just an asset of huge economic value but of culturally priceless significance for the people of Australia. Therefore, despite failing at a project level, the Sydney Opera House project has been a marvelous success at an operational, business, and strategic level in the long run.

Additionally, the use of a multidimensional approach for assessing project success at different points in time is considered a useful approach to assess the success of projects at the project management level as well as at the success of the project to the organization strategically. A multidimensional evaluation of project success, according to Zwikael and Meridith (2021), will enhance performance evaluation of projects by distinguishing between the short- and long-term results. Figure 1.3 shows a classical example of the multidimensional approach to project success measurement.

Figure 1.3 Example of a dimensional approach to project success measurement

Source: Shenhar, Dvir, Lever, and Maltz 2001

Figure 1.3 shows that time-dependent project success is divided into four dimensions. The first dimensions measure the efficiency of the project during execution and after completion of a project. The second dimension measures the performance level after the project has been delivered to the client. The third dimension is focused on the contribution of the project to the business and achievement of the benefits the project was set out to achieve such as efficiency gains, revenue generation, improvement in margin, and so on. The fourth dimension is used to measure the success of the project after a period of time (e.g., two or three years) after completion of the project.

Therefore, a multidimensional approach to project success measurement in addition to a multistakeholder view of project success is recommended. This will enable measurement of success of the project at the right level of analysis, from the right perspective using the relevant success metric and at the right time horizon/stage of the overall project life cycle.

Need for This Book

This book was written following the author’s experience for more than 20 years in the field of project control, project management, commercial management, academia, and major projects advisory and consultancy across many industries as well as carrying out a PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) research into project control practice in the UK (see the section titled “Overview of the Research Underpinning the project control inhibitors management (PCIM) Methodology and Applicability of This Book” later in this chapter for an overview of the research). The reason for the research and then this book is that most research in relation to project delivery success have focused generally on the causes of cost and time overrun and project success factors. These usually only provide a view of the superficial aspect of factors that can enable project success without focusing on inhibitors and factors that need to be controlled. Consequently, much of the guidance available to project control practitioners have focused mainly on general project management practice with project control usually getting a passing mention. The implication of this is that there is a general lack of guidance on issues surrounding the execution of project controls in practice and how practitioners can deal with the factors that may inhibit effective project control in practice.

Additionally, project control is also discussed generally in pockets of either techniques such as critical path method (CPM), earned value management (EVM), performance evaluation and review technique (PERT), cost-value reconciliation, and so on (see Chapters 7 and 8 for more on these techniques) or software packages such as Microsoft Project, Asta Powerproject, Primavera P6, and so on. Project control is rarely discussed as a whole practice, but these techniques and software packages in isolation do not form the project control system or practice. There are other issues that combine with these techniques and software tools to constitute the project control practice of a project or an organization. Some of these issues include how the techniques and software packages are deployed, the organizational environment where project control is implemented, the planning and estimating process, and the factors that hinder or support project controls. The author’s view is that there is a lack of a comprehensive project control framework that considers the whole project control system with recommended good practices for all aspects of the project control process.

Furthermore, most books related to project control have been devoted to explaining project control concepts, tools, and techniques but not the factors that make it difficult to use these tools and techniques in practice. This book focuses on addressing these shortcomings by presenting a project control framework that looks at project control as a system affected by factors and develops mitigation for these identified project control inhibitors. The book also concentrates on guiding practitioners on how to implement project control successfully by providing good practices for various aspects of the project control process. Additionally, one of the most important advantages of using this book is that it not only focuses on cost, time, and scope control, concepts, and application in practice, but it also goes into a great detail on the enabling environment in practice to achieve effective project control. This book is filled with practical best practices that can be used during the project control process.

Introduction to the PCIM Methodology for Effective Project Control

To enable the implementation of a comprehensive project control practice, it is important to consider the project, the project control process/cycle, project control techniques, and software tools as well as the environment where project control is taking place. The PCIM methodology has been developed to achieve a comprehensive and integrated view of project control practice. The PCIM project control approach is described in detail in Chapters 4 to 6 with reference made to it all through this book; however, it is introduced in this section to provide readers with an overview.

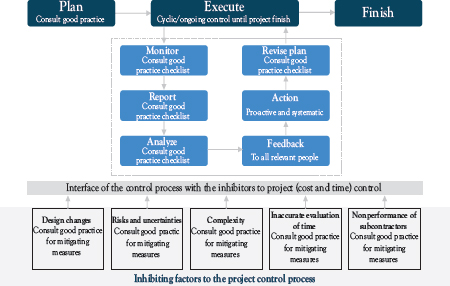

The underlying hypothesis of the PCIM project control methodology is that the project control process is not a closed system and is affected by factors in the environment where the project is taking place and the controls environment of the organization. Furthermore, the PCIM asserts that even with the most sophisticated project control techniques and tools, there will be inhibitors to the project control effort. This is because projects do not take place in isolation and are affected by the wider environment. Therefore, the PCIM project control methodology hypothesis is that to control a project successfully, it is important to recognize the need to identify and manage the factors that inhibit project practitioners from effective project control. The PCIM methodology framework is depicted by Figure 1.4. The PCIM project control methodology is focused on the following aspects:

• The project phases, which are the primary phases through which a project proceeds (planning, execution, and completion) and are depicted by the top section in the PCIM framework;

• The primary project control steps (monitor, report, analyze, feedback, action, and revise plan), depicted as the middle section of the PCIM framework;

• The factors that inhibit effective project control (in essence, the environment under which project control is implemented and reflect the fact that project control is not a closed system and is often inhibited by some factors), depicted as the bottom section of the PCIM framework.

Figure 1.4 PCIM methodology framework

It is important to note that the PCIM project control methodology is not just superficial, but it includes several good practices that can be used to manage and mitigate each of these project control inhibitors (see Chapter 5) as well as good practices to support practitioners through the major steps of the cyclical project control process (planning, monitoring, reporting, and analyzing) (see Chapter 6). Finally, the PCIM project control methodology is not rigid, it is flexible and scalable as the methodology underpinning it can be used as a blueprint and adapted for projects in various industries or countries.

Overview of the Research Underpinning the PCIM Methodology and Applicability of This Book

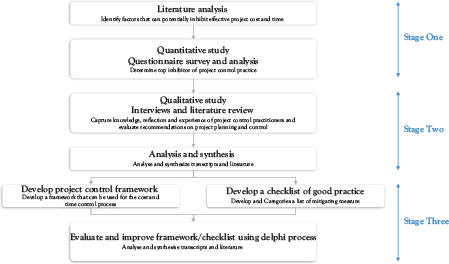

As stated previously, the PCIM project control methodology emanated from a PhD research on project control practice that was carried out over a five-year time frame in the UK. The doctoral research followed a rigorous three-stage process (as shown in the Figure 1.5) that utilized a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodology, and a range of research methods.

Figure 1.5 The PCIM project control methodology research process

First Stage: Literature Analysis and Quantitative Study

The first stage of the research was used to establish the top inhibitors of project cost and time control practice. By initially using a literature analysis of hundreds of empirical research studies, many factors that can potentially inhibit effective cost and time control were identified. After which a questionnaire survey was used to establish the leading factors that hamper practitioners from controlling effectively the cost and time objectives of their project in practice and to obtain information on project cost and time control practice in the UK construction project industry. The questionnaires were administered to 250 construction project organizations in the UK by company turnover/company fee earnings and completed by highly experienced construction project practitioners within these organizations. The analysis of the returned questionnaires showed that 64 percent of the responding practitioners were construction project contractors who had more than 25 years of experience and 69 percent of responding practitioners were construction project consultancies that had more than 25 years of experience.

Second Stage: Qualitative Study (Interviews) and Synthesis

The second stage of the PCIM research process utilized semistructured interviews to explore the topical issues revealed by the questionnaire survey and unveiled further, the experiences of practitioners in relation to project control in depth. The same sample of companies used for the survey stage of the research was used. A total of 15 companies offered relevant project practitioners for interviews, ranging from construction directors, project directors, commercial directors, to senior project managers. Most of the interviewees were experienced employees of their companies (construction project contractors and construction project consultancies). The total professional experience of the 15 interviewees was 402 years (an average experience of nearly 27 years).

Third Stage: PCIM Project Control Methodology Development, Evaluation, and Refinement

The PCIM framework and methodology development process commenced at this stage by first modeling the results of the analysis carried out during the first two stages of the research to produce an initial preliminary framework for project cost and time control. The preliminary framework was refined iteratively based on synthesis of the findings and analysis of the questionnaire survey, interviews, the author’s experience, and further literature analysis. Several good practices were also developed to support the various aspects of the PCIM framework (to form the PCIM project control methodology). The PCIM project control methodology was then presented to construction project practitioners for evaluation and validation using the Delphi technique, a systematic technique that enables experts to reach a consensus on various opinions (see Chapter 6 for more on the Delphi process). The Delphi process helped generate more input to further improve the PCIM methodology, validate the model and develop a good practice checklist, and to reach a consensus on the significance of each of the practices.

Applicability of This Book to Different Industries

Finally, although the research underpinning the PCIM project control methodology was conducted in the UK construction and infrastructure project industry, the author has endeavored to make this book useful to readers from other industries. Many of the chapters of this book cover general project control topics that are applicable to many industries. Additionally, the author has many years of experience of working and consulting on projects in many industrial sectors (such as financial services, IT, facilities management, pharmaceutical, academia, construction, government, energy, telecom, consultancy, and so on). Therefore, the author has used his diverse experiences across these sectors to influence the content of this book.

Organization and Overview of This Book

This book is a two-part applied book organized into 12 chapters. The first part of the book (Chapters 2 to 6) is focused on how to achieve effective controls using the PCIM project control methodology and accompanying good practices. The second part of the book (Chapters 7 to 12) is on the classical and general techniques used during project control followed by the concluding chapter. The content of each of the chapters is described below.

Part One: Achieving Effective Project Controls Using the PCIM Project Control Methodology

Chapter 1: Introduction

This chapter provides a background to the book by first introducing the concept of project control and its importance during projects. The reasons for utilizing project control are followed by an explanation of what is meant by project success and the approaches that can be used to view project success. The chapter then goes on to explain the rationale for the book. This is followed by an introduction to the PCIM project control methodology followed by an overview of the research that informed its development.

Chapter 2: Fundamental Concepts of Project Control

The theory and key concepts that underpin project control are presented and discussed. The chapter starts by explaining the relationship between project control and project management, followed by an explanation of the types of project control and articulation of the classical factors controlled in a project. The chapter concludes with a detailed discussion of the project control cycle including its constituent steps.

Chapter 3: Project Control in Practice and Prevention of Challenges to Effective Project Control

This chapter provides an overview of project control in practice including the prevailing time and cost control practices, including their shortcomings. The chapter also accentuates one of the hypotheses of the PCIM project control methodology by asserting that project control does not operate in a vacuum and demonstrates this by providing insights into the day-to-day barriers that make effective project cost and time control challenging from a practitioner’s perspective. Several good practices that can be used by practitioners to deal with these challenges are also recommended.

Chapter 4: Using the Project Control Inhibitors Management (PCIM) Methodology to Improve Project Control in Practice

This chapter emphasizes the fact that project control is not just about utilization of a technique, but that it is a complex process that requires human interventions, decisions, and practices, and the process is usually inhibited by many factors. The project control inhibitors management (PCIM) framework is presented and discussed as an approach that can be used to manage projects more effectively. The process and thinking used in the development of the PCIM project control approach is also discussed.

Chapter 5: Good Practices to Mitigate the Foremost Project Cost and Time Control Inhibitors

This chapter starts by reinforcing one of the hypotheses of the PCIM project control methodology: project cost and time control will be more effective if project control processes in organizations are accompanied by practices to enable success. To this effect, the foremost project cost and time control inhibitors are discussed and classified as well as an overview of the research that identified them. Furthermore, 100 good practices that can be deployed during project control to mitigate the foremost cost and time control inhibitors are presented and discussed.

Chapter 6: Good Practices for the Cyclic Project Control steps; Planning, Monitoring, Reporting, and Analyzing

The chapter presents a set of 65 good practices for the major steps of the project control cycle (planning, monitoring, reporting, and analyzing). This chapter also reports on the Delphi process that was conducted to evaluate, validate, and obtain consensus on the significance of each of the developed good practices for the key steps of the project control cycle.

Part Two: Classical Techniques Used During Project Control

Chapter 7: Classical Project Time Control Techniques

This chapter presents and describes the various project time control techniques such as Gantt bar chart, line of balance (LOB), CPM, program evaluation, and review technique and others. The chapter also provides an assessment of these techniques to reveal their applicability, advantages, and shortcomings.

Chapter 8: Classical Project Cost Control Techniques

This chapter presents and describes the various project cost control techniques such as unit and standard costing, cost and value reconciliation, EVM, and others. The chapter also provides an assessment of these techniques to reveal their applicability, advantages, and shortcomings.

Chapter 9: Project Scope Management

This chapter presents and describes the scope management process and discusses concepts like scope initiation, scope planning, scope control, and the work breakdown structure (WBS). It concludes by highlighting good practices in relation to scope control on projects.

Chapter 10: Risk Management

This chapter presents a detailed explanation of the risk management process including the subprocesses of risk identification, risk analysis, (including some relevant qualitative and quantitative techniques), and risk response. Concepts such as risk categorisation, risk classification, risk tolerance and risk appetite are also discussed.

Chapter 11: Overview of Supplier Performance Management, Business Case, and Benefit Management Processes

This chapter starts by focusing on some of the key project management processes that are important for and support project control. An overview of supplier performance management, the business case process, and benefits management are provided.

Chapter 12: Ingredients of an Effective Project Control Environment

The book ends by discussing the key ingredients for an effective project control environment and argues that these should be put in place by organizations to give their project control effort the best chance of success.