8

Learning How Interaction Works in Technology-Enabled Care Teams

After education, it is time to work. MoM TiSH is sending us to the first job.

We studied the principles of shared mental models and applied these to design new platforms as a common ground for building sustainable healthcare – since that’s what this book is all about. In the previous chapter, we elaborated on the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) model as the main shared mental model, including the interaction between people, technology, and systems. A platform is more than just a collection of components; it’s the interaction between the components and users that makes it come to life. We will learn all about these interactions in the health journey in this chapter.

We will discuss how the transformation task force can stimulate the community of care teams to share how they interact or want to interact with other actors in the healthcare ecosystem. We will do so by following the team and the activities throughout the health journey using the Journey Interaction Matrix (JIM).

In this chapter, we’re going to cover the following topics:

- Defining interactions in activities

- Shaping the journey for care teams and patients

- Exploring the roles of team members and patients

Defining interactions in activities

To get input for the platform development process, the Dev in DevOps, the task force organizes sessions to collect the stories from the potential users. The task force gives the care providers the opportunity to share what they need for their activities at certain touchpoints in the health journey.

For a common understanding, the OODA model is used. To get a structured story, we introduce the JIM. This is used to reason about the possibilities and formulate stories. These structured stories are used in the development process for the exploration of solutions and subsequent Quality Functional Deployment (QFD) and specifications, as explained in Chapter 5, Leveraging TiSH as Toolkit for Common Understanding.

Let’s find out what the input for Dev is.

To achieve this, you could rely on generic metaphors, such as the village of blind people encountering an elephant and trying to describe it. However, it then still doesn’t necessarily lead to the required shared understanding. The awareness of a specific situation itself is a good starting point for putting some effort into the storming phase of Tuckman’s team development phases – we discussed Tuckman in Chapter 5, Leveraging TiSH as Toolkit for Common Understanding. The resulting understanding based on shared mental models is the norm to be able to perform.

In the previous chapter, we discussed the OODA principles for building system components and defining their interoperability and integration on each tread of our TiSH Staircase.

To avoid spending too much time in the storming phase in a team, you need a starting point for the process from which you can evolve into the norming phase. Formal models such as OODA can serve this purpose, as was our reasoning in the former chapter. At least, it jumpstarts the process of either using the models presented or rapidly finding other models that provide the required shared understanding for the problem to be solved.

In Chapter 7, Creating New Platforms with OODA, we brought forward the OODA principles for building system components, defining their interactions in terms of interoperability, and integrating on each tread. This will also be the central principle in this chapter on interactions between the activities of the Technology-Enabled Care (TEC) teams.

What we do is divide the activities into four categories, the OODA steps. On the user level, the interaction is in the activity and the interoperability and integration are between the activities.

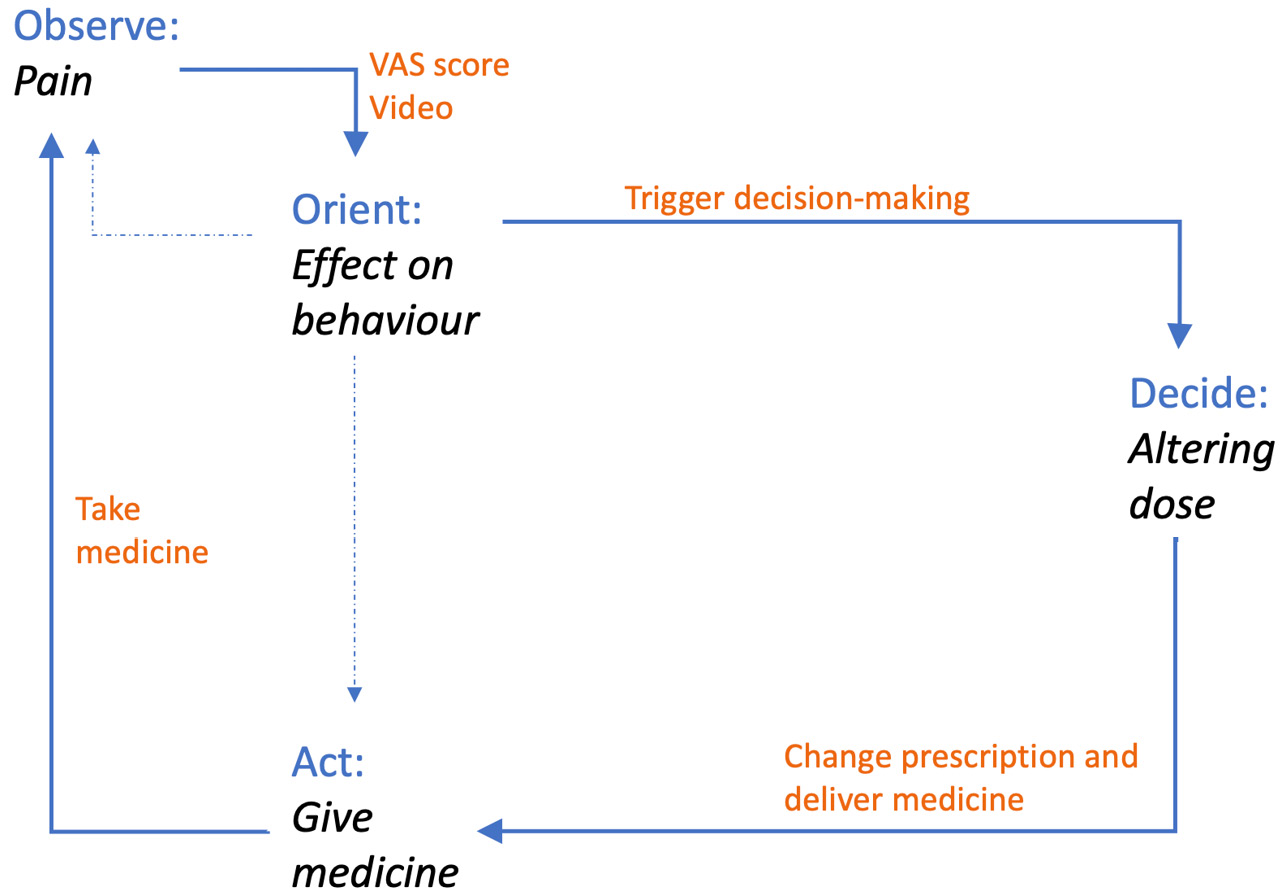

In Figure 8.1, we find a very simple health journey to demonstrate. Observation consists of determining how much pain the patient is in. Next is to orient on what to do about the level of pain. If the pain affects behavior too much, then the pain killer dosage can be altered, resulting in giving a certain dose of medicine.

If in the orientation, the effect on behavior is not so much, then no action is needed, or it was time to give the medication anyway. These are the implicit guidance loops of OODA. No formal decision is required.

The lines between the OODA activities are significant for the enabling functions. The patient has to communicate their level of pain. A common way to do that is the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) or VAS score. It’s a scale between 1 and 10. The behavior also has to be captured by video or text entry. Sending the information triggers orientation. If it is decided that the medicine should be altered, then this triggers an activity with the pharmacist:

Figure 8.1 – OODA activities

We have learned how important it is to see these interactions in order to realize feedback loops. It starts with the availability of digital data in the first place if we want to make workflows in the enabling platform.

The challenge lies in the ever-increasing ways of observing and processing the acquired data and using that data in feedback loops.

There’s a risk that we must consider in evangelizing digitization and that is that the possible overload and distraction on the actual job will lead to the inhibition of change. To avoid this, digital interactions must be intuitive and quick. If prior to interaction, the information has to be extracted from one or more systems in a cumbersome way and it takes (too much) time to prepare the data to be comprehensible and ready for interaction, then the data will probably be left unused.

Three are three major prerequisites to the use of data if we want to make an impact on workflow:

- Registration of data must be very easy and fault-free

- Accessibility or retrievability is quick and reliable with syntactic interoperability

- Comprehensible to sender and receiver with semantic interoperability

The data must be actionable – as in, consumable, believable, and usable for decision-making (the sender or receiver can take action on the data presented). There is no question about the authenticity, accuracy, or completeness of the data. The data must also be integrated into the workflow so that collection, transfer, and consumption are seamless and integrated into decision cycles. This requires not only digitization of the systems involved but also re-tooling of people through training and exposure and a rework of processes.

Shaping the journey for care teams and patients

The journey is one of continual health over a full lifetime. Already in Chapter 2, Exploring Relevant Technologies for Healthcare, we defined the Health eXperience (HeX) as the continuation of health and the services around it. These services optimize the HeX for as high a number of patients or clients that a care team can attend to as possible. Demand is driven in terms of improving health, lifestyle, and participation. This is done with flexible resources and a broad range of available technology-based support services. Services are coordinated within the ecosystem micro-communities. This requires activities and interactions between those activities.

With the OODA activities in mind, we need a way to structure the stories we get from the work floor. A structure derived from the HeX and health journeys, triggered by events in the health condition, is built on the interactions in the touchpoints within these journeys. We introduce the JIM that is presented in Figure 8.2, which can be used to define interactions along the journey. We use seven W-questions to define the journey:

- Why is the journey needed? What events led to the problem that has triggered a health assessment and defines the treatment and any associated care or health plan? There has to be a clear starting point in a journey to give meaning to the other questions. What are the goals in terms of health, lifestyle, and participation?

- Who is taking part in the journey? The patient is surrounded by many actors who are all concerned with the health of the patient. Think of informal caregivers (as in, next of kin or others in the social network), nurses, practitioners, or specialists from several care providers. Typically, procedures are confined or siloed in an organization, but we must take full advantage of all available resources around a person and what they can do with each other for this person.

- What do they have to do; what is the purpose of an action or activity? For example, exercising as part of the care or health plan or monitoring a heart condition. These are typically the medical protocols, procedures, and steps in related processes. Consider these to be the genetic heritage. These activities use the OODA categories.

- When are they required on the journey? This requires the availability of the patient and the actors from the Who question as well as the enabling technology. Coordination is required in some form of planning or scheduling processes.

- Where will the journey take place? What are the touchpoints at home, in transit, or in the practice or hospital? A small question but with a big impact on the ability to keep as active as possible and on the flip side of the coin, the impact on health provisioning outside specialized buildings, such as practices and hospitals.

- Which enabling technology resources are required in this journey and are they available for use as intended? The enabling technology consists of the traditional medical equipment, although now connected more and more to devices carried around by people, as we described in Chapter 1, Understanding (the Need for) Transformation, categorized as the Internet of Things (IoT). We are experiencing many innovations in the field of healthcare and it is these innovations that make the transformation possible. The Which question is key to enabling a great HeX with the platform.

- How to make it work? How are the workflows made with seamless interoperability and integrated interactions? The answers to this question are the customer objectives as input for the specifications. This also includes the objectives for the following:

- User interfaces

- Data availability and accessibility

- Interactions for well-defined communication, coordination, control, and command

- Connectivity between the resources

To recap, the first six questions starting with a W provide the specifications for the interactions. The how question translates these to fulfill the platform interaction given the resources, time, and place that we have defined.

Explaining the JIM

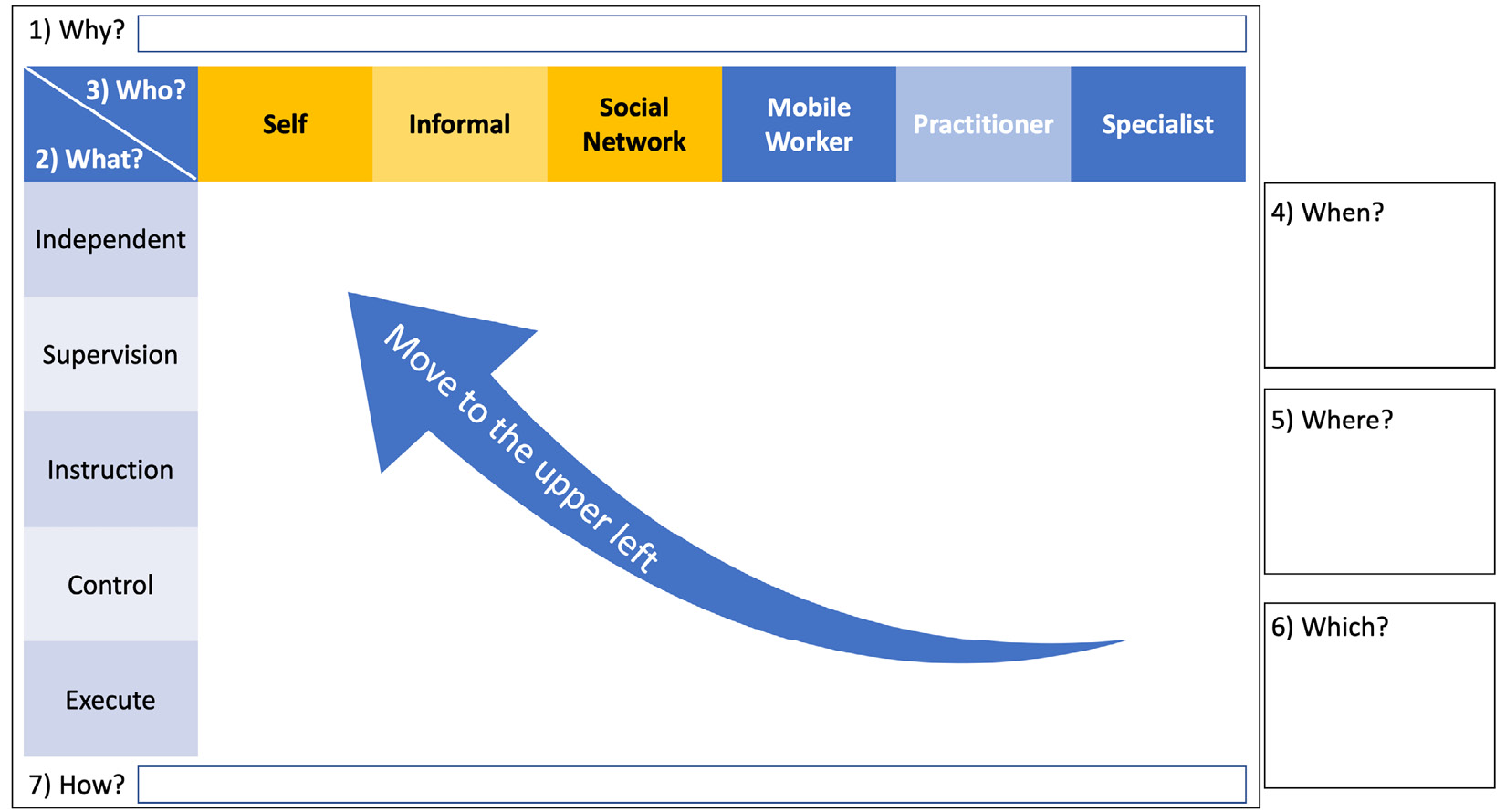

In this section, we will explain how to use the JIM, a method that emerged from the daily practice of the authors. It projects customer journeys on the seven W-questions, starting with the following figure:

Figure 8.2 – JIM for plotting touchpoints on the health journey

The JIM starts with the question of why a health journey is needed, with a purpose such as rehabilitation from injury. With this purpose in mind, the touchpoints of the journey are plotted in the matrix with the two axes. On the horizontal axis are the interactions divided into who is doing the interaction, in terms of classes of skills and costs. It starts with the patient, followed by the informal caregiver, social network, remote or mobile workers, and practitioners, and ends with the medical specialists. This ordinal sequence in costs can be used to define a lean journey with action shifted to the left as much as possible.

The vertical axis represents the intensity of care needed to classify the types of what activities. It ranges from independent self-care via supervision of the patient’s actions or instructing the patient step by step to controlling the actions of the patient hands-on or activities being executed by someone other than the patient. Supervision means just attending to see whether activities are done correctly and the expected results are obtained. Instructing means active communication with the patient. Control is, for example, safeguarding safety or physically helping the patient, and executing is about the patient taking a passive role and somebody else acting and taking care. Think of a nurse giving an injection. Obviously, lower intensity of care is better if possible, as this will have lower costs. The center of gravity of the journey must be moved to the upper left as much as possible given the circumstances. Notice that both axes are about someone and not something – in other words, they are about human activity and interactions. Human interactions are in the touchpoints of the journey.

Each matrix cell (the Who or What classifications) describes the OODA activity interaction at a touchpoint in the journey, with When and Where added, and with Which enabling technology. For example, in the Mobile Worker/Supervision matrix cell, we Observe whether the patient is taking their medication at home (Where) on time (When) by monitoring the alarm from the medication dispenser (the Which enabling technology). If required, in the case of medication not being taken (Orient), remember or instruct the patient to take the medication (implicit guidance to Act).

The interaction definition also mentions a device or thing, a medication dispenser (Which). These dispensers contain medicines that are required for each medication moment. For diseases such as Parkinson’s, the exact timing of medication for the individual patient can increase the effectiveness significantly, resulting in being able to be more active. This kind of dispenser is usually placed at home (Where) and connected (How) via the internet to a pharmacy, for example. The How question is about the digital interaction, interoperability, and integration to enable the health journey to be a good experience.

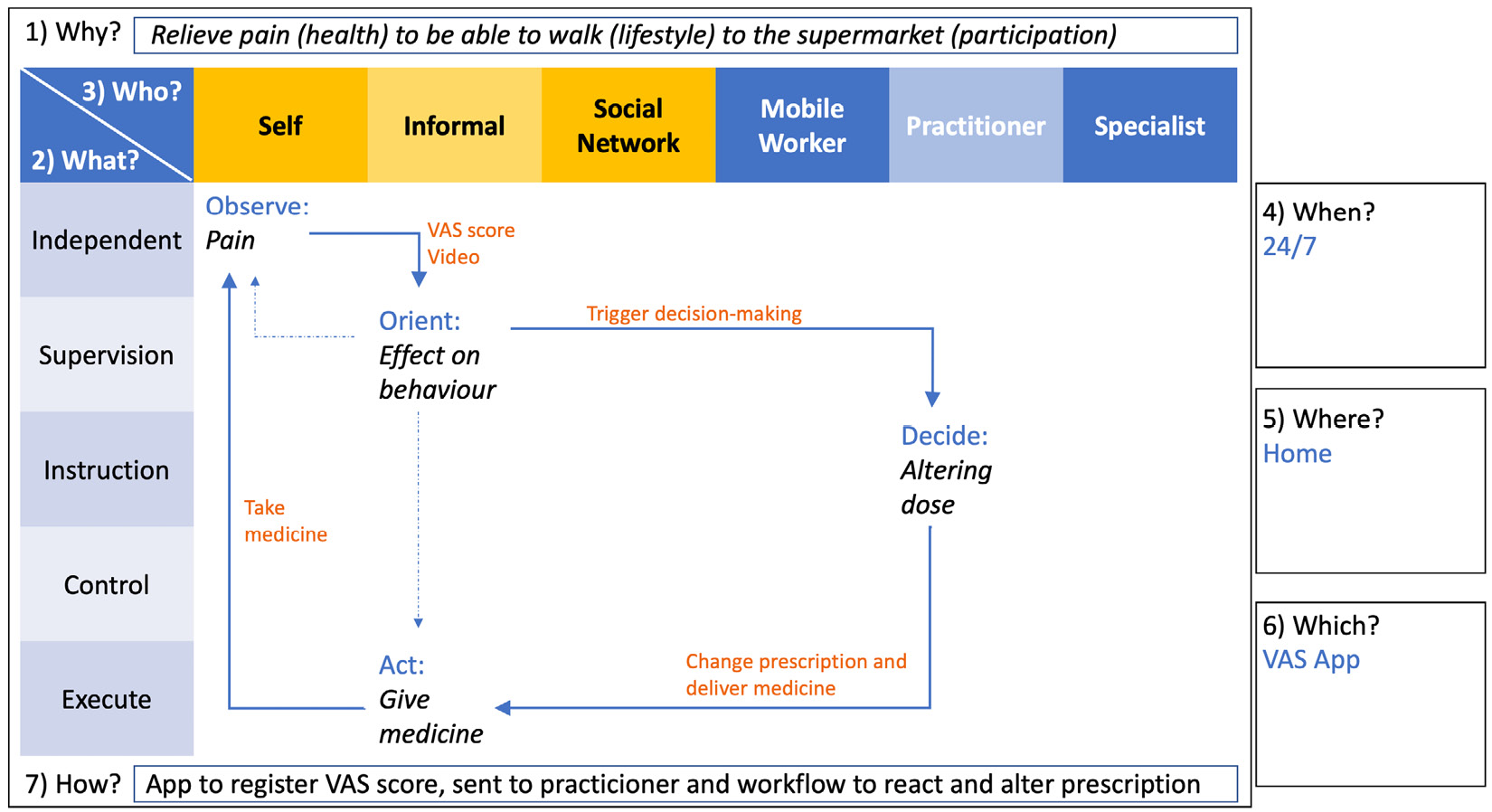

Let’s make this tangible in an example given in Figure 8.3 of a complete journey where we have a patient that needs to recover from a knee operation:

- The target is that a patient is exercising as part of rehabilitation treatment after surgery. The aim is that the patient is doing these exercises at a time that is convenient. The patient can do the exercises at home with the use of a tablet to show them instructions. The exercises are recorded on video and it is requested that they fill in a questionnaire with the VAS score. The patient’s aim is to walk again soon and be able to go to the supermarket.

- The observation is focusing on the pain experienced. If, for example, the exercises are done as part of recovery after an intervention such as surgery, then the exercises shouldn’t jeopardize the healing of the wound. The VAS score and video taken of the exercise give a good indication of the amount of pain. It’s the partner of the patient who is attending to the task of evaluating this and if required, sends a message to the practitioner.

- The practitioner receives the VAS score, video, and message from the partner and decides to decrease or increase the pain medication. This decision is processed via a workflow including the pharmacist and instructions are given to the partner, who attends to giving the medication manually.

This results in the following JIM. We recognize the OODA activities in Figure 8.1, but now in the context of the answers to the seven types of questions:

Figure 8.3 – A JIM with rehabilitation journey OODA loops

We learned in Chapter 6, Applying the Panarchy Principle, that resources have to be available so that people are not frustrated in the transformation process. The required enabling systems have to work.

Digital enablers determined in the JIM example given include the following:

- Tablet or smartphone with an exercise app including the VAS questionnaire and video app

- Electronic Patient Registration (EPR)

- Planner(s) of the closed-loop medication process

- Connectivity

By defining the journey using interactions at the touchpoints in terms of OODA loops, an integrated view is created of patient-centric care provisioning. This integrated view is used to design the architecture for the development of interoperability-enabling digital technology. We will explore this further in the following sections.

Enabling the journey with DevOps

In the previous section, we described how to define a journey that a patient could go through to be able to participate fully in society again, delivered by the ecosystem of networked care. For this, we need DevOps, in that technology is dynamically and carefully allocated to the specific journey in the ecosystem and made available, easy to use, and fully managed so that users needn’t worry about the appropriate support of devices and software.

We need a process to steer the DevOps process for this purpose. Maybe in one organization that is in place, however, the DevOps process and the demands of the complete ecosystem are different. Sometimes referred to as the whole system in the room, with all organizations involved we have indeed caught the complete story of the ecosystem.

The mechanism is the 4Care part of DevOps4Care, Support, Experience, Value and Tell as in Figure 3.3. The feedback loop consists of the following:

- Support by managing the availability and use of the deployed, enabling technology

- Experience by observing how interactions in tasks and activities occur in practice

- Value by evaluating the experience compared to what is expected and required

- Tell by communicating with users about how valuable the outcomes of DevOps are and how these outcomes can be improved

Let’s elaborate on this a bit further, as it is essential in DevOps4Care in networked care.

Support: Normally, for each care provider after deployment, including the onboarding of end users, the operation consists of organizing support with a proper service desk, including the self-help portal, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs), and chat functions, but also the involvement of the digicoach role in the extended support team. When collaborating in the ecosystem and ensuring closed OODA loops, this becomes more complicated. The challenge is to coordinate all operations as if they were done under one entity. In Chapter 9, Working with Complex (System of) Systems, we will come back to this.

Experience: The experience is determined by the use of all enablers such as the tablet, app, and connectivity used in the interactions during the journeys that we described. Experience is measured by how effectively the enablers can be used to realize the cross-organization OODA loops. Besides the objective fulfillment of a process, it is important to know whether something is not working or experienced well. We should not solely address the technical side but also look for what might be the underlying cause with the Knoster, Rogers, Moore, and Mezirow models in mind and address the problem, need, or inhibition point for a solution, as described in Chapter 6, Applying the Panarchy Principle.

Value: Next is the value of the experience in terms of the value creation stages given in Chapter 3, Unfolding the Complexity of Transformation:

- Personal value – as in, job satisfaction and security

- Fulfilling the requirements and ability to support the team

- Supporting the activities in the workflows within the guidelines and protocols

- Determining the results of treatment or intervention

- Customer satisfaction in terms of the quality of care delivered

- Improving the quality of life of the patient

- Outlook on the participation of the patient

For each of these stages, instruments are available to capture the value. The Groninger Wellbeing Indicator (GWI) (by Joris Slaets), consisting of two questions, is a good example of such an instrument:

- Which of these areas are important to you?

- Good sleep and rest

- Enjoying eating and drinking

- Pleasant relationships and contacts

- Being active

- Caring for yourself

- Being yourself

- Feeling healthy in body and mind

- Enjoyable living

- Are you satisfied in these areas?

It’s an example of a true HeX used by some nursing homes in the Netherlands. To close the feedback loop, the third question is, if not satisfied, what are we going to do about it?

For example, a person is hiding possessions such as hearing aid, glasses, and dentures before going to sleep because they are important for eating and having contact. In the morning, the patient forgets where they were hidden, due to a memory-related condition. It leads to the wrong conclusion that they have been stolen, causing anxiety. Nursing personnel can’t always find these possessions either, taking up valuable nursing time either way.

The solution was to hide the possessions in a secure locker for this person before sleeping and return them in the morning. In this case, it was the interaction with the next of kin using the GWI that gathered that the patient suffered from anxiety. Together with next of kin, the care staff oriented on why this was happening, explored possible solutions, and decided to act. This was registered in the electronic record (EHR) to be used in the daily planning of nursing activities. In this case, it resulted in a happier patient and less burden on the nursing staff for the final 2 years of this elderly person’s life. Fewer care activities meant an improved quality of life in this case!

Tip

For a deeper understanding of the Dutch healthcare system and its challenges in terms of digital transformation, read The transformation of elderly care: The impact of digitalization by Harry Woldendorp. It can be found here: https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/The_transformation_of_elderly_care/91czEAAAQBAJ?hl=en.

Tell: The final step of feedback in DevOps is communicating what can be improved. This is the game-changing mechanism driving the transformation that we know so well from DevOps and agile working, again, in concert with the entire ecosystem. Here, community builders have a big task – organizing so that everyone involved in a closed OODA loop is heard. A JIM session is designed to do that. It will give a common understanding of the requirements needed to design and develop the enabling platform as a whole.

The feedback will drive the development of the microservices. Ultimately, somewhere in the future, the digicoach, e-nurse, or lead user can detect what improvements are wanted by zero-coding the microservices themselves. This requires building a digital twin following the shared mental models first. This will also take several steps to achieve. The people, teams, and organizations will have to learn the skills and go through their own transformational learning process.

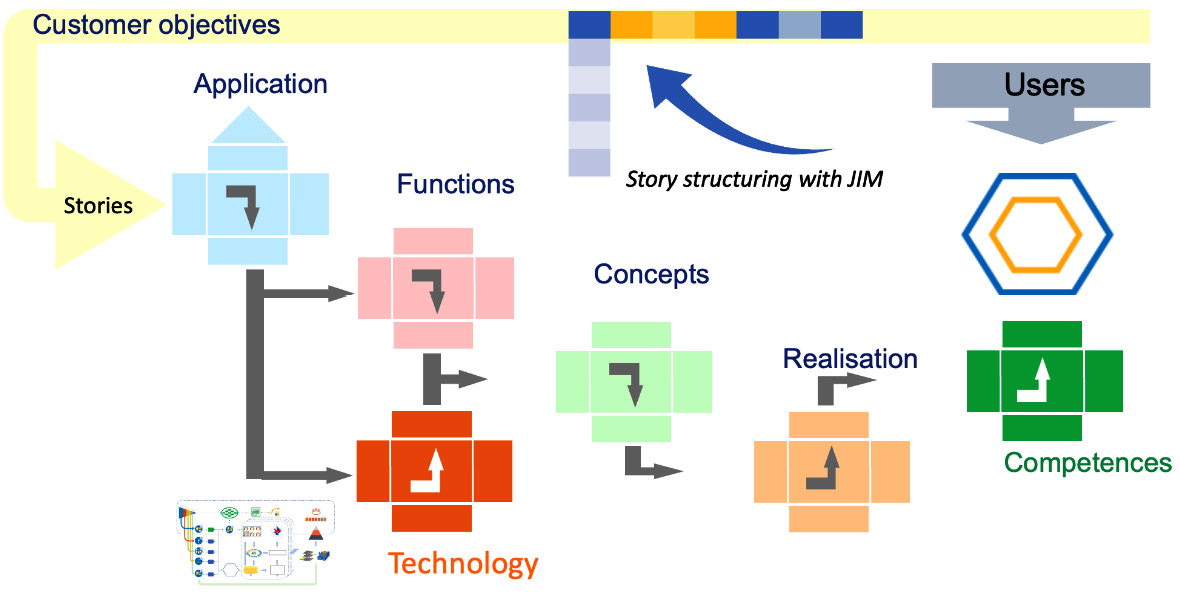

At this point, we will refer once again to the Customer Objectives, Application, Functional, Conceptual, Realization through Reasoning Exploring Qualifying Specifying (CAFCR REQS) model. Exploration is the layer where the stories are told and a priori solutions are suggested. Creating explicit exploration JIM sessions within the organization and collaborating is a good start to implementing the communication link between care and DevOps. These sessions can evolve by using simulations with the digital shadow to determine the impact of possible solutions and prepare to code the improvements in the next release, following the trend of automated DevOps.

The results of the JIM sessions are the input for development where, once again, developers from all transitions have to coordinate the actions and pace. Testing will have to be done not only on their own component or system but will also have to be fully integrated to enable the closed OODA loop:

Figure 8.4 – JIM stories as the input requirement for platform development

Here, the systems engineers come in again, especially in engineering management, which focuses on how to design, integrate, and manage complex systems over their life cycles.

A coalition of organizations grows from an ad hoc group via collaboration towards cooperation with ever more complex systems. It will take time to learn how to manage these complex systems together.

In the end, it should result in daily or even hourly releases to follow the dynamics required for adapting and forming care networks based on a person’s health experience. We will come back to this in the coming chapters.

In this section, we discussed the different interactions and actors in the OODA activities to realize the 4Care feedback to DevOps. These actors all fulfill particular roles that must be defined in the systems that we will be using. Actors with different roles as patients or as part of the TEC teams – together with the responsibility to provide the closed OODA loops. The following section will explain how to define these roles and why this is important.

Exploring the roles of team members and patients

Now, why is it important to define roles from the perspective of OODA? We already saw that we have various actors defining actions based on observations and orientations, leading to decisions. These actors can perform optimally when they have access to the right tools and data. Care is optimized when actors work together in the chain or network of care, using the right tools and data, as it is integrated into that chain. The interactions in the activities in the chain define the care and the execution of the activities by the right actors defines the quality of the care. Actors and activities need to be able to interact.

Roles need classification in order to be assigned the right attributes, to be identified properly, and to get access to the right resources in terms of the closed OODA loops along the journey.

We therefore use a known way of working in healthcare in which the OODA loop is intrinsically present – social alarming. Social alarming is well established and therefore a good model for getting a shared understanding of redefining the roles. It provides the structure to build the OODA loop, as social alarming contains all steps required.

The responsibilities of the service chain process from onboarding, providing a service, to ending the service with social alarming or TEC mechanisms in general are well defined in standards such as the European CEN/TC 431. There is a firm focus on the users ensuring an improved level of health experience in the health journey.

The standard CEN/TC 431 achieves this by working with all interconnected parts in the entire service chain, or loop as we call it for social care alarms. A link to this standard is provided in the Further reading section.

Technology and organization structure independence are important features of this standard – the service model for social care alarms. Using this service model, we – instead of reading social alarming and reacting to alarms – can interpret it as health service reacting to events.

The technology-enabled health service typically follows this path:

- Initiated, resulting in acquiring the required enabling technology to enable the defined loops of the initiated journey

- Used in the journey of healthcare provisioning enabled by management and support

- It is assessed whether to continue, change, abort, or re-initialize the healthcare service

- Ended, resulting in the healthcare service being terminated

For our purposes, it suffices to distinguish the enabling roles:

- Supplier of equipment, devices, and application services

- Installation and activation service of endpoint equipment used at the premises of the actors

- Health event monitor and action dispatcher in the care network, such as present-day remote Intensive Care Units (ICUs), ambulance response, and other community alarm or telecare services.

- Technical Operations (Ops) coordinator of the end-to-end management of the feedback loops

- Provider of the technology-enabled response health services

Each of these plays its role in the deployment of services, including onboarding, supporting, and managing the enabling technologies. With the enabling technology in place, the user or actor roles in provisioning the actual journey with health services are divided into the following:

- Observe whether an event has occurred defined in the journey

- Orient what this event signifies

- Decide on who is going to respond and how

- Act accordingly as defined in the journey

Here, the OODA shared mental model comes in on the technology side too. To assure the proper working of the enabling technology for the closed OODA loop healthcare provisioning, the same sequence is used:

- Observe whether an incident has occurred, disturbing the proper working of the enabling technology in such a way that the feedback loops are going to be affected

- Orient on what the root cause of the incident is

- Decide on who is going to respond and restore the proper functioning of the enabling technology

- Act accordingly to restore the feedback loop

In this way, the processes mirror each other on both the medical and technical side, creating a better mutual understanding.

Of course, this has to be managed end to end over the entire platform.

Summary

In this chapter, we focused on the members of the different TEC teams and their interactions. We explored the roles and tasks of these teams and how they can support the patient during the health journey. These teams operate in ecosystems – hence, they need to be interoperable and interact with different actors in the entire health journey that provides the health experience for the patient. The teams are supported by technology, so we must ensure that operations are in place to assist the teams in working with technology and help whenever an issue occurs. Lastly, the technology needs to be improved per evolving demands and the requirements of the patient. This is exactly what DevOps4Care envisions.

In this chapter, we introduced the JIM. By answering the questions why, when, where, and which, the right care is defined. Obviously, this is done by observing the patient and orienting the situation or circumstances, the steps we discussed in the OODA loop.

We discussed how to capture the stories from the users as input for the development process, spanning the whole ecosystem, and we discussed how roles are divided in both the healthcare provisioning and enabling technology operations in this kind of ecosystem.

We will discuss interoperability and interaction in those ecosystems further in the next chapter by deep-diving into the concept of micro-enterprises and their enabling platforms.

Further reading

- Multi-Cloud Architecture and Governance by Jeroen Mulder, Packt Publishing

- Big Data for Architects by Bhavuk Chawla, Packt Publishing, 2021

- IoT and Edge Computing for Architects by Perry Lea, Packt Publishing, 2020

- CEN/TC 431 - SERVICE CHAIN FOR SOCIAL CARE ALARMS, CEN: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/tc/cen/732920f7-04dc-4e4c-b100-788999bc1bce/cen-tc-431

- We recommend reading the work of Maaike Kleinsmann on this topic of common understanding: https://www.tudelft.nl/io/over-io/personen/kleinsmann-ms