10

Assessments with TiSH

Our career in transforming healthcare is really taking shape. It’s time to tell MoM TiSH how it is going.

We will explore the elements that we need to assess and how to perform assessments, all in good preparation for the transformation. For this, maturity models are introduced with emphasis on the approach of the Industry 4.0 Maturity Index. This combines multiple maturities on different themes such as technology, culture, organization, and collaboration to devise a program of activities to allow networked care to grow toward maturity in a balanced way.

We will learn what maturity is, how to get a joint picture of the current maturity, and how to translate that to the next coordinated steps. With this, we can make the transformation into an actionable program of projects and apply it in our daily practice.

In this chapter, we’re going to cover the following main topics:

- Understanding and defining maturity assessments with TiSH

- Performing assessments

- Maturity-driven program management

Understanding and defining the assessments with TiSH

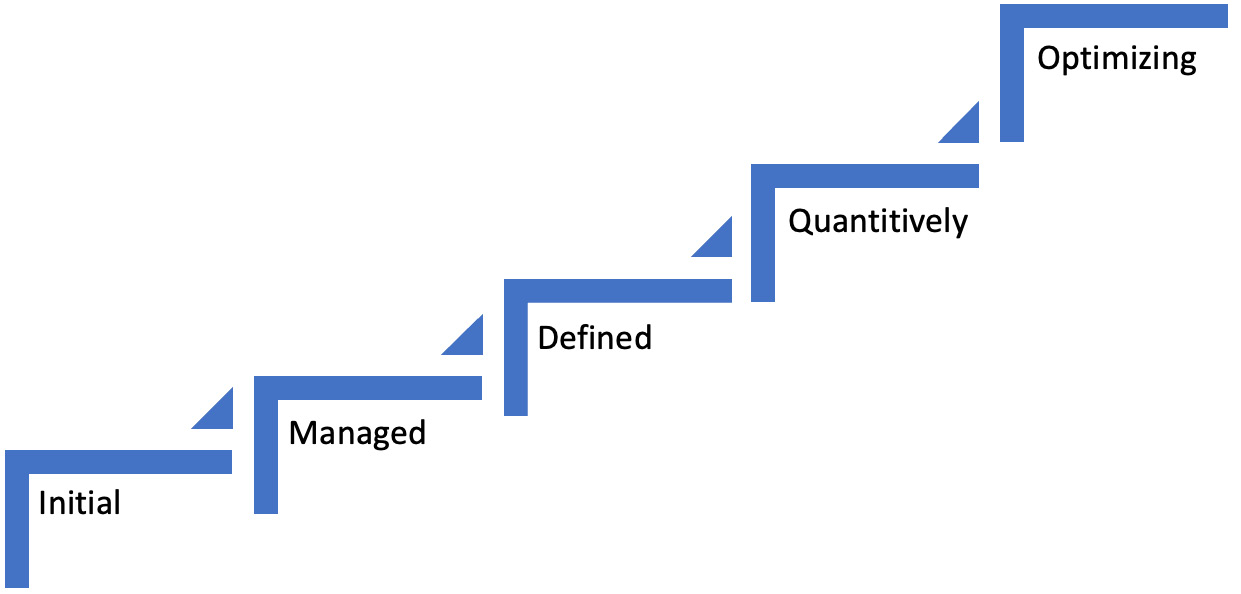

Maturity models are one instrument to plan or influence transformation, by determining where we stand today and where we want to go. The most well-known maturity model is the Capability Maturity Model (CMM), which basically defines at what level organizations have matured in software development. However, CMM is used more widely than just in software development, and frankly, the principles of CMM are quite commonly used in other terrains as well.

As you can see in the following diagram, the TiSH staircase has been inspired by it.

Figure 10.1 – The five levels of the CMM

The basic level of the maturity model is Initial. At this level, processes are not well defined. Outcomes are unpredictable since processes are poorly controlled and highly reactive. The next level in CMM is Managed. In CMM, it means that processes are defined per project but still very reactive. Even worse, since they are defined per project, organizations constantly need to reinvent the wheel for new projects. Processes are not generic.

The next level is Defined where processes are proactive and applicable for organizations and, in our case, collaborations as a whole. The final levels are Quantitively managed where processes are controlled, and outcomes are measured and ultimately continuously Optimizing. At this highest level, organizations and collaborations can focus on value creation.

In short, organizations start with ad hoc, uncontrolled processes and, via repeatable processes, eventually grow their maturity to proactive, measurable, and foremost predictable outcomes that can be used to continuously improve these outcomes – first within the organization and then adding value in collaboration and cooperation with others.

Maturity models come in all sorts, including models for security and DevOps processes. Systems engineering has also been put into the Software Engineering Institute Capability Maturity Model Integration (SEI CMMI) framework, which also follows the five levels covering how well the capabilities are developed to engage in the engineering of complex systems.

Many generic models on digital transformation have been developed as well, such as Gartner’s Analytics Maturity Model and many more under the collective name of Digitalization Maturity Model (DMM). Specific to healthcare, the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) developed several models:

- Adoption Model for Analytics Maturity (AMAM)

- Continuity of Care Maturity Model (CCMM)

- Supply Chain Model (CISOM)

- Digital Imaging Model (DIAM)

- Infrastructure Adoption Model (INFRAM)

- Outpatient Electronic Medical Record Adoption Model (O-EMRAM)

- Electronic Medical Record Adoption Model (EMRAM)

These models are prescriptive frameworks for healthcare organizations to build their digital health ecosystems. Healthcare Information Management Systems Society (HIMMS) uses eight-stage (0–7) maturity models that operate as a development roadmap and offers global benchmarking. TiSH, on the other hand, is a conceptual nonprescriptive frame of mind for building a common understanding between stakeholders of medical and social care, health enterprise, business, and technology.

Tip

For more detailed information on these models, refer to https://www.himss.org/what-we-do-solutions/digital-health-transformation/maturity-models?gclid=CjwKCAjwh-CVBhB8EiwAjFEPGYWSlAdXR-VgHQqDhZmXCT8fKFPZj738u_pRv3CKNtWRjx9oj_tFeRoCP1oQAvD_BwE.

Another example emphasizing the collaboration of organizations in supply networks is the Industry 4.0 Maturity Index, developed by Acatech and also referenced in Vision35 of INCOSE. Acatech looks at the maturity of several structural areas at the same time on the scale of the collaborating and cooperating supply networks. The addition to HIMMS is their integral view on a set of maturities.

Acatech defines four areas with two principles each, by which the Industry 4.0 maturity is determined:

- Resources:

- Information systems:

- Organizational structures:

- Culture:

Based on the current capabilities of these areas, organizations can plan their development path of processes and organizational structure to increase the maturity in Industry 4.0. The index itself has six stages of all maturities combined:

- Computerization: In our terms, digitization.

- Connectivity: For workflows in processes.

- Visibility: What is happening, and seeing or observing others in the network.

- Transparency: Why it is happening, and understanding.

- Predictive capacity: What will happen, and being prepared.

- Adaptability: How can an autonomous response be achieved? Self-optimizing.

In TiSH, we have analog seven treads wherein the first equivalent Acatech stage is covered by two treads. We make a distinction in the resources: digital human skills and technical specifications of devices and the capability to use them in the work within teams. At the organization’s tread in the TiSH staircase model, we connect the providing teams to each other and with the enabling teams and their systems. Visibility is how well the care provider organization can communicate with the care network about what is happening. Transparency coincides with the need for coordination in stepped care. Predictive capacity is needed to be prepared and control the individual demand for integrated care. Adaptability allows to autonomously respond with the required measures for a healthy and participating population and the individual people therein.

We use, however, in the stage of reasoning and exploring the models we have put forward in the previous chapters to characterize the maturity of the organization and networked care. This is to facilitate the common understanding in a multidisciplinary setting prior to using the formal models in the qualification and specification, as in CAFCR REQS (Customer, Application, Functional, Conceptual, Realization and Reasoning, Exploring, Qualifying, Specifying). Remember Figure 5.13 for this. As our main purpose is the health experience, we can translate the Industry 4.0 maturity stages for exploring the development path toward the TiSH staircase of Chapter 1, Understanding (the Need for) Transformation. Let’s recap what we have learned.

Figure 10.2 – TiSH as the maturity exploration framework

The first tread is about skills and the right devices for one-to-one activities in care delivery. Think of single-task digitization as an eConsult or a medication dispenser. It’s about interacting digitally with the Point-of-care.

The second is the teams that learn to work together by informing each other what to do and dividing labor among them based on feedback. Buurtzorg teams are autonomous to divide their labor supported by digital planning and scheduling, or as in real-time Uber-style fulfillment without planning, such as the Roamler Care approach.

Thirdly, the organization connects and enables the teams to work on the same Point-of-care together by sharing real-time insights digitally via electronic patient records, or respond to events triggered by social or sensor alarming.

Being on this third tread doesn’t mean that there is no Electronic Patient Record (EPR) or social alarming in treads one and two. In the first or second tread, the EPR is often used for quality registration purposes to be able to show the quality of care and comply with regulations. The EPR is not much used in the direct interaction with the Point-of-care. In the second tread, it might be used to store the results of questionnaires or retrieve information when preparing for a new interaction, maybe as a result from a social alarm. The difference on thread three is that it’s real time.

On the fourth thread, the group of teams acts as single entity, meaning rebundled, to the Point-of-care and digitally visible for the ad hoc care network. They communicate what has happened. The group is part of the case management or performs the role of the case manager itself.

This evolves in the next treads into transparent digital insights in formal Stepped Care collaborations with predictive required capacity, Integrated Care with simulations and algorithms, and Directed Care with adaptable resources autonomously directed from the Point-of-care, all with managed closed loops.

The position on the staircase must be backed by the underlying characteristics, as we have discussed so far in our models. We can group these models into four similar structural areas, each with two principles as two sides of the same medal, recognized in the following:

- Humans:

- Using on one side the health experience stages, from a one-on-one activity to combined distributed care networks, resulting in Directed Care. See Chapter 3, Unfolding the Complexity of Transformation.

- Using on the other side the monetized value staging as given in Figure 3.4 from individual earnings to outlook on participation. See Chapter 3, Unfolding the Complexity of Transformation.

- Grow:

- The size on one side for which the assessment is applicable, including individuals, teams, organizations, collaboration, cooperation, community, and society. See Chapter 6, Applying the Panarchy Principle.

- The planning of growth on the other side as given in Figure 5.9 from scenarios in campaigns on participation and translation into missions, vision, goals, strategy, tactics, and operations. See Chapter 5, Leveraging TiSH as Toolkit for Common Understanding.

- Digital:

- Digitization on one side as put forward in Table 7.1 and Table 7.2, from acting, deciding, orienting, observing, and the loops on observing results, diagnostics, and treatments. See Chapter 7, Creating New Platforms with OODA.

- Complexity on the other side in interoperability and integration from components, subsystems, systems, and engagement systems of systems at tree level, forest level, mission level, and campaign level. Refer to Chapter 3, Unfolding the Complexity of Transformation and Chapter 8, Learning How Interaction Works in Technology-Enabled Care Teams.

- Control:

- Networking and enabling platforms on one side, from the frontend workplace on the edge, back-office applications, and connectivity to the outside world to communicate, coordinate, control, and command care networks. See Chapter 9, Working with Complex (System of) Systems.

- Governance on the other side, with individuals skilled to work in autonomous TEC teams organized in case management, stepped care, integrated care, and directed care. See Chapter 9, Working with Complex (System of) Systems.

These four areas form the sentence humans grow enabled by digital control – this sentence is a good reminder of our human measure.

The following table gives an overview of all areas and principles presented in this book. We can identify in each of the seven treads the characteristics of each of these principles.

Each cell of the table can have its own maturity level, but this can very quickly become a meaningless exercise, drowning ourselves in the sheer amount of poorly understood data. We need the overview to gain insight:

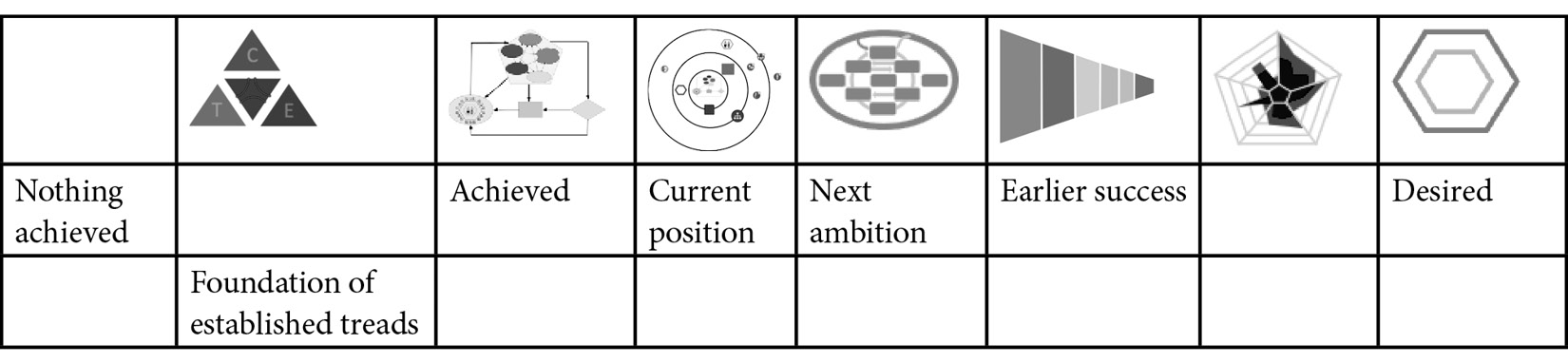

Legend:

Table 10.1 – Maturity board

The maturity has been color-coded with an example of the maturities measured in a qualitative way. Bright green is deployed and blue is piloted, fading via orange for a prototype to light pink in the idea stage. White means that this is currently not a topic. In the next section about performing assessments, we will explain this.

Relating ambition to risk

To establish the position, we can use maturity to set the level of ambition. However, here comes the warning: ambition in achieving maturity can also introduce risks. Stretching to achieve goals set by ambition can lead to frustration in organizations, teams, and individuals, but can also result in failures, impairment, and serious damage where even patients might be severely impacted. For example, you don’t want to end up in a situation wherein the security of implants will be compromised. Part of defining the maturity levels is defining the acceptable risk level and introducing proper risk management – proper in this case meaning that human measure and safety are the leading principles.

Proper risk management starts with acknowledging that processes start initially poorly documented, ad hoc, and based on non-integrated policies and systems. The first step to take is to get to repeatable processes that are well defined and can be controlled. As with CMM, the final level in risk management is optimized, where closed-loop processes lead to predictable outcomes and risks can be identified, quantified, and mitigated with strategy and best practices. Only by complying with risk management, organizations, teams, and professionals will we be able to create and work in a coherent digital ecosystem. How do we mitigate this?

We’ve discussed the content and use of maturity models such as CMM, HIMMS, and Acatech. Again, these models are very formal. For use in a quality system and risk management, this is very useful. For transforming, we need a culture of a more hands-on actionable approach appreciated by people.

Culture is also more expanded in Society 5.0 in Japan: “A human-centered society that balances economic advancement with the resolution of social problems by a system that highly integrates cyberspace and physical space.” This view is influential on transformation into sustainable healthcare. That’s why we utilize maturity in an appreciative cultural approach in reasoning and exploration but still use the valuable insights from Carnegie Mellon, HIMMS, and Acatech.

Our human measure approach uses positive health experience as a merit. For this, the teams who interact with patients or clients and their community must balance the use of technology as an enabler during exploration. How are we going to achieve that balance? That’s the topic in the next section.

Performing assessments

Before we dive into the assessments, let’s recap some of Chapter 4, Including the Human Factor in Transformation, and Chapter 5, Leveraging TiSH as Toolkit for Common Understanding. In Chapter 4, Including the Human Factor in Transformation, we introduced Customer Objectives, Application, Functional, Conceptual, Realization (CAFCR) with the Requirements (REQS) layers to turn TiSH into a thinking framework. In Chapter 5, Leveraging TiSH as Toolkit for Common Understanding, we introduced the reasoning approach. In fact, the assessments serve a purpose in this reasoning approach. The reasoning gives the assessments meaning in the exploration of specific details.

First, we identify the dominant need or problem as a starting point. The initial need can be to establish what the position is on the TiSH staircase. We look at the CAFCR views on the following:

- Customer objectives, as in individuals digitally interacting with each other using the Activity Triangle to structure stories

- Application requirements on the entities and relationships of the enabling system of systems, using Figure 9.4 in Chapter 9, Working with Complex (System of) Systems

- Functions from actors, sensors, controllers, and use cases creating value through closed OODA-loops with the Journey Interaction Matrix (JIM)

- Conceptual decomposition into the entities (refer to Chapter 9, Working with Complex (System of) Systems)

- Realization in an enabling system of systems, including an operations framework and defined provisioning entities

The reasoning thread iterations require explorative assessments such as the following three methods, which we will discuss in more detail:

- Qualities checklist to create insights

- Scaling questions to analyze stories and establish facts that deepen insights, next to testing assumptions through simulation in models and measurements of actual use – the evidence backing the stories

- An appreciative inquiry to ask the why, what, how, when, which, where, and other questions to broaden insight

For the integration into the qualities of Quality Function Deployment (QFD), as we defined in Figure 5.11, more prescriptive maturity models as sub-methods are needed, such as HIMMS or CMM, to define and extend the reasoning thread. We will not cover that in this book and refer to the sources in the tip given previously and later on in the Further reading section.

Qualities checklist for readiness

The next question is how to define the current levels in an organization or determine the readiness for the desired position. A quick scan method for this is by working through a questionnaire. We define five stages in this questionnaire:

- No topic or evidence of it

- Have some ideas (imaginable) worked out in slideware

- Proof of concept in an experimental project (feasible), including a prototype, report, or publication

- Pilot on a small scale (usable, maintainable, and cost structure), subsidized by an organization and/or external funding

- Deployed (applicable, manageable, affordable, and enabling infrastructure in place) with contracted care

The following diagram shows these levels in an innovation chain and associated criteria, which was first introduced by A.W. Mulder, a lecturer at The Hague University of Applied Sciences.

Figure 10.3 – Five stages identified in readiness

For each of the cells, the status can be asked of one or more persons. If they choose a certain level, they must consider how to substantiate this by being able to show evidence of activities. Each cell gets an appropriate color, as shown in Table 10.1.

Scaling question assessment

The second method is the use of scaling questions. It’s used in therapy and when coaching people and is also suitable to assess the present, past, and future of teams, organizations, and collaborations. It is straightforward by determining the following:

- On which tread, stage, or level do you think the organization stands?

- What has been achieved previously?

- In what situation or circumstance was nothing achieved?

- What was an earlier success?

- What is the next ambition?

- What is ultimately desired?

The following table provides guidance on how to register the preceding questions:

Table 10.2 – Scaling question of which TiSH tread an organization is

This scaling question instrument can be used in practice by laying out the eight (0–7) treads on the floor, with each tread about a meter apart, either indoors or outdoors. Now each person can walk the scale and you can observe which position each person in the group takes, indicating where they think the team, organization, or collaboration is at. By exploring together why they have determined the current position, we can establish what has been achieved to date, what earlier success was achieved, and what the next ambition could, should, or must be.

Everyone in the group can ask questions or comment on it. Intervision methods can be useful here. Exploring in a group gives insights into each other’s opinions and views. It’s a good way to start getting a mutual understanding. The models that we presented earlier are used to project what has been told. This starts the consensus process to reach agreement on the current position and the next step.

This walking the scale must be done for all eight characteristics to form the maturity board, as shown in Table 10.1, leading to a more comprehensive common understanding and insight.

Appreciative assessments

The third method is the use of appreciative inquiry borrowed from the psychiatric discipline, either in interviews with individuals or groups. It has developed into a powerful transformation tool that can also be applicable outside psychiatry. Here, we apply it to assess the maturities.

It builds on what has already been achieved by individuals, teams, organizations, and collaborations. The scaling questions are good input for the more elaborated appreciative assessments.

The 5Ds of Define, Discover, Dream, Design, and Deliver fit nicely into the DevOps4Care process: define the topic or theme, development is the design, ops is delivering, and the dream is the feedback via telling (remember the 4Care steps of experience, value and tell) from the discovery of experience and value in 4Care provisioning. This way, we can make assessments part of DevOps4Care. In fact, the qualities checklist as part of REQs – reasoning, exploring, qualifying and specification – fits in monitor of Ops, and scaling questions are an effective instrument to explore 4Care.

Appreciative assessments go one step further, as they make feedback happen. With feedback, we think again of OODA. And yes, we can express appreciative inquiry in terms of OODA, as shown in the following diagram.

Appreciate the current position and earlier successes, imagine or dream about what could be done, design your future, and create in the ecosystem micro-communities. Combined with self-reflection (Grant), we use OODA to create the loops required for the transformation.

Figure 10.4 – Appreciative assessment and self-reflection

OODA is not only used to model care but also, in Ops, to model the operations, as seen in Chapter 9, Working with Complex (System of) Systems, and now the maturity of DevOps4Care itself.

By observing or monitoring the maturity, it is evaluated. Implicit guidance consists of do more what has worked so far, changing the goals, or deciding to change what’s not working. An action plan is made to explore the ideas, build a prototype or conduct a small-scale pilot to test the change before deploying it.

During orientation, every new insight has to be appreciated and celebrated to create a positive attitude to change. This is where the name of the method is derived from: everything that has been done or thought through well is appreciated. The previous methods of scale walking and readiness are the inputs for this method. Again, all eight characteristics must be assessed as different viewpoints on maturity and how it is appreciated.

And of course, we can perform a deep dive with the prescriptive maturity models that we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. But it’s important to maintain a mutual understanding. We can always use TiSH to present the results of these deep dives in a way that resonates with other disciplines and their viewpoints and knowledge.

This brings us to what to do with the results of the reasoning and exploration using assessments. That is the topic of the next section.

We conclude this section with the remark that to establish a common understanding of maturity, a task force should use professionals proficient in using the three assessment methods of a readiness checklist, scaling questions, and appreciative inquiry.

Maturity-driven program management

To engage in transformation, we will use the insights given by the assessment we talked about in the previous section. The question is how to plan the next actionable step from the current position, as concluded in the assessment. We do that by planning the ideation, prototype, pilot, and deployment projects.

We know that development has two sides. It’s the maturity and the factors that can inhibit a development path. To stay focused, we have to concentrate on constraining maturity and/or inhibitions. In discussing constraints, we will use Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints (TOC) and keep things actionable.

The takeaway from TOC is to know what bottlenecks are likely to hinder progress. Every system has a limiting factor or constraint. TOC helps with five focusing steps, which, when customized for our transformation, are as follows:

- Identify the constraining maturity and/or inhibition for the next TiSH tread.

- Exploit this constraining maturity and/or inhibition.

- Subordinate everything else to this constraint.

- Elevate the constraint.

- Don’t stop now and find the next constraint.

We have determined the maturity with the methods introduced in the previous section. What we have not yet done is find the possible inhibitions for the maturity development path.

Let’s go back to Chapter 6, Applying the Panarchy Principle, where we learned to spot inhibition points in the panarchy. The inhibition points on the ecocycles can be considered bottlenecks. For example, in countries with an aging population, the inhibition point currently is the lack of healthcare personnel. Therefore, we have to make optimum use of the personnel that is available through digitalization. However, the lack of IT personnel creates an inhibition point too in the available technology to enable care.

With this knowledge, we have to make use of what is available in technology and personnel and exploit this as much as possible. We can use the available cloud services and concentrate on using them to eliminate any waste in the care processes and improve the outcomes of their work, maximizing the direct interaction time with patients where the human touch is most needed and automating all other tasks as much as possible.

Transformation of this kind means disruption. Throughout this book, we have advocated unbundling organizations into micro-enterprises and re-bundling them into ecosystem micro-communities. We advise having a look at Geoffrey A. Moore’s book Zone to Win. Moore defines four zones to create – or facilitate – disruption and to get organizations to start investing and exploring new ways of working. The four zones are shown in the following ecocycle diagram:

Figure 10.5 – Moore’s zones and readiness in the planning ecocycle

The first two zones are the performance and the production zones. These zones aim for sustainment; they basically keep everything the way it is and do not disrupt but change gradually. The big risk here – remember the section where we talked about risk management – is that organizations in these zones will be disrupted from the outside. Other new organizations will invest in new products and services, addressing the changing needs of people’s health.

Organizations must get to the disruptive zones, starting with the incubation zone, where these changing needs of patients are explored and new propositions are created. In this incubation zone, the organization purely invests. It’s in the transformation zone where these new propositions and forthcoming solutions are prototyped, gaining more traction in the healthcare ecosystem and reaching more patients for feedback.

However, from the transformation zone, organizations will enter the performance zone again at a certain point. In other words, organizations will constantly have to re-invent themselves to keep up with changing and ever-increasing demands. This is extremely hard for big organizations with a monolithic architecture. Hence, we must unbundle and re-bundle into agile operating micro-enterprises, supported by a microservices architecture.

The four zones have their own leadership style. If these leadership styles are not addressed and all zones are not executed in parallel by different types of people, the inhibition points will manifest. Planning the ideation, prototypes, pilots, and deployment must be allocated along the teams in the different zones. As incubating, transforming, and (learning to) perform are costly, cooperation with other care providers can start the next step in networked care.

Of course, here we can find a constraint where some organizations are not letting go or not investing in overcoming inhibition points. Differences in maturity can be the reason for this.

On the collaboration scale, one organization can become a bottleneck. Again, the focus is on utilizing this organization and elevating this constraint by either a different division of labor and/or one organization learning about the other organization.

To recap: program management enables projects in the four different zones to address the identified lowest maturity and inhibition points, all with the purpose of building the two sides of the following:

- The health experience Ecosystem Micro-Community (EMC) around every individual – the HeX at the points of care along the touchpoints of the journey

- The solution ecosystem micro-community to deliver medical and social care in some form of networked care

The terms experience and solution ecosystem micro-communities are used in the Rendanheyi-model to distinguish between the care-facing micro-enterprises and the enabling micro-enterprises. In the next chapter, we will elaborate on this.

In an organization, there are always one or more teams who are motivated to try something else. Take one of these teams to incubate new ideas and give them room to transform themselves on a small scale. Their example can be used to pilot a new approach with other teams, and after performance is proven, the rest of the organization or collaboration can follow. With this, the variation in maturity across teams can be put to good use. However, they have to take into consideration what the transformation of all teams will cost in time and resources.

Start small and learn to grow the maturity of the rest of the organization. This is true for building health experience ecosystem micro-communities and for enabling ecosystem micro-communities. To avoid that for every single health experience different enabling systems are developed, which is unsustainable, it has to build on the foundation of the cloud with its generic services.

We mentioned the constraint of the lack of enough IT workers. Cooperation on this with other care providers in the community is a way to start working on the shared services platform and avoid reinventing the wheel in each organization and every health experience. Here, we embrace the cloud strategy. Let’s explore this cloud foundation.

Data and applications will have to be hosted somewhere and the way to go is in cloud environments. Organizations might host their own apps and data or use data coming from various sources. Organizations will also use Software as a Service (SaaS) applications that are hosted in various environments. This landscape is what we call multi-cloud. Make no mistake: almost every organization is already multi-cloud-oriented. They might use Microsoft Office 365, Salesforce, or other Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) applications, and data connected to diagnostic equipment, or even Electronic Patient Data (EPD) that is hosted in cloud environments.

All of this must be operated and managed. It becomes even more complex when organizations develop their own applications using DevOps methodologies, including Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment (CI/CD) software pipelines. Organizations must grow their maturity in operating these complex environments in order to enable professionals and patients to work with the systems.

In maturity models for multi-cloud governance, we focus on pillars or scaffolds, following the best practices of cloud adoption frameworks that are issued and maintained by major public cloud providers such as Microsoft Azure, AWS, and Google Cloud Platform (GCP). These pillars contain the following:

- Cost optimization

- Security and compliancy

- Utilization and scaling of resources

- Automation

These frameworks are guidance in moving systems to the cloud and transforming applications and data in the cloud in a way that allows cloud resources to be optimized. Cloud adoption frameworks (CAFs) typically start by defining a strategy, then planning for transition and transformation, and finally governing and managing resources – literally taking an organization by the hand in transition and transformation. The strength lies in connecting processes, services, products, and organizations with supporting (cloud) technology, resulting in increased operational efficiency.

Tip

The CAFs of Azure and AWS can respectively be found on https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/overview/cloud-enablement/cloud-adoption-framework/ and https://aws.amazon.com/professional-services/CAF/.

As every organization has to do this, it’s a great opportunity to start collaborating and cooperating on the solution enabling side. This brings focus to the operational healthcare activities of the Technology-Enabled Care (TEC) teams.

Let’s use an example to illustrate this.

We will use Table 10.1 and now explain the colors of the cells. This care provider has made an assessment with the scaling questions and has concluded that the lowest maturity is the digital area, in digitization and complexity, digitization scores orient level in regards to complexity, where only a prototype has been made to observe the real-time circumstances of the patient. A pilot is underway to have a better overview of the whole complex application landscape to turn it into a consistent system of systems.

The next step is to go for remote monitoring of patients at home. Some experience has been gained in a pilot conducted on integrated care in a consortium. This was a subsidized project that ended last year. Activity trackers and vital sign measurements were part of the project. However, another organization of the consortium provided these.

The insurance company did a pilot on lowering costs in this project. An experiment was conducted to build a prototype to receive the monitoring data directly in the EPR. This experiment failed, but the project was considered a success, as it increased knowledge and common understanding.

The conclusion was that more investments are needed in digitization to be able to observe patients in real time. The bottleneck is that although IT operations are sufficient, they lack the development capacity.

The organization is now discussing whether to invest in development. The inhibition is that it is unclear what the consequences are in terms of value. Reduced claims read as less income for the organization.

It is decided to do a more comprehensive appreciative assessment and make a plan for the mid to long term for the transformation, in not only being able to do remote monitoring but also to investigate collaboration with other care providers and the local government responsible for social care.

In the next chapter, we will explore this further and apply all that we have learned so far.

Summary

In this chapter, we learned what maturity models are and how we can use them to define the maturity level of organizations and teams, and also how to set an ambition to reach the next level. In order to define maturity, we must do assessments. Basically, we should know where we’re coming from if we want to determine where we are going – the very essence of any transformation. We learned to use the models in assessments from a checklist, scaling questions, appreciative assessments, and how to plot results on prescriptive maturity models such as CMM and HIMMS.

We learned how to look at maturities of different aspects and sizes to plan for a program of transformation projects. We can define actions to identify the inhibition points and utilize them as much as possible. As a result, we can make a balanced program of ideation, prototypes, pilots, and large-scale deployment projects.

In the final section, we introduced the ecosystem micro-communities and learned how to motivate these to move through various performance zones, continuously improving services and eventually providing better, sustainable healthcare by making use of shared services and resources, such as cloud technology. In the next chapter, we will further discuss these micro-communities.

Further reading

- CMMI: https://www.cmmiinstitute.com/

- Zone to Win: Organizing to Compete in an Age of Disruption by Geoffrey A Moore

- Appreciative Inquiry: https://positivepsychology.com/appreciative-inquiry-process/

- Theory of Constraints Institute by E. Goldratt: https://www.theoryofconstraints.org

- Industrie 4.0 Maturity Index. Managing the Digital Transformation of Companies – UPDATE 2020: https://en.acatech.de/publication/industrie-4-0-maturityindex-update-2020/download-pdf?lang=en