8

Leveraging Your Buying Power

This chapter will help you understand the main drivers of sustainable IT vendor management and procurement and its role in the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) agenda. By leveraging your buying power, you can influence your supply chain of IT vendors to address environmental and social issues and do so openly and consistently.

The main objectives of this chapter are to introduce you to the different facets of sustainable IT vendor management and procurement and how these disciplines can be leveraged to make your supply chain more trustworthy and transparent.

In this chapter, we will cover the following topics:

- Drivers for sustainable IT vendor and procurement management

- Essential IT sustainability requirements

- Sustainable IT procurement from start to end

- Sustainable IT vendor management

- IT vendor management sustainability scorecard

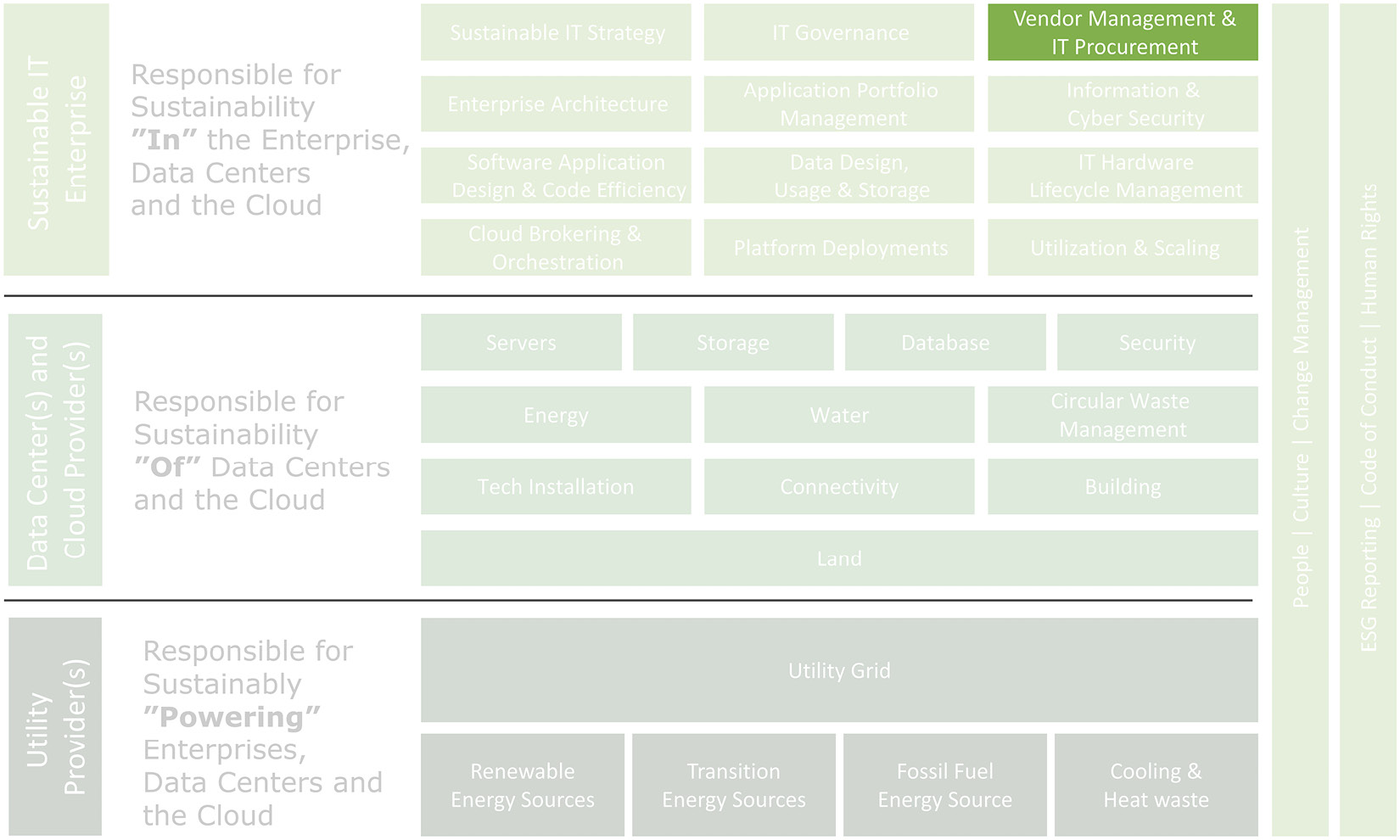

This chapter’s sustainable IT reference model perspective, as illustrated in Figure 8.1, will primarily cover IT sourcing and procurement within the Sustainable IT procurement from start to end section. We will look at how these capabilities can play an integral role in influencing your IT supply chain and directly and indirectly influence your Scope 3 emission:

Figure 8.1 – Sustainable IT reference model – Chapter 8 focus

By the end of this chapter, you should have a better understanding of what the drivers for sustainable IT vendor management are and how you can leverage your buying power in your IT supply chain to make it more trustworthy and transparent.

Secondly, you will understand which essential IT sustainability requirements are from a corporate commitment, environmental, social, product and service, and circularity perspective that could be leveraged. Thirdly, we will look at sustainable IT procurement from start to end; just leveraging three simple steps can make your IT procurement much more robust and sustainable. Furthermore, you will understand that sustainable IT vendor management can bring about impactful ESG changes in your entire vendor ecosystem if managed well. Finally, we will summarize this chapter by looking at some key sustainability metrics that could be leveraged to maximize ESG impact, minimize risk, and reduce cost.

Drivers for sustainable IT vendor and procurement management

The IT supply chain is very complex, with multiple delivery networks joined at the final assembly. Before the product reaches the end user, the material travels from mines to smelters, refineries, and subcomponent manufacturers to the final assembly before it is packed and sent for distribution. As a buyer, this poses a lot of risk in your IT supply chain to ensure that suppliers maintain high environmental and social standards connected to the sourced product. Violation of labor laws such as child labor, extensive overtime, poor and hazardous working conditions, and negative environmental impacts are a few examples that can introduce significant risk for the buying party that can impact your bottom line, reputation, and brand. Managing these risks poorly and inconsistently may significantly impact your company’s relationship with customers, employees, investors, and other key stakeholders.

As a buyer, you must act strategically, mitigate risk, and promote sustainability. By leveraging your buying power, you can influence your supply chain of IT vendors to address environmental and social issues and do so openly and consistently. Unfortunately, greenwashing and bluewashing are two reoccurring phenomena, and the reoccurrence within the IT supply chain is no exception.

Greenwashing versus bluewashing

Greenwashing is the practice of deceptively issuing false or unverified claims by branding something as environmentally friendly when it isn’t.

Bluewashing is the practice of deceptively issuing false or unverified claims regarding a company’s commitment to responsible social practices when that is not the case.

These terms are often used interchangeably. In the United Kingdom, Canada, and Singapore, legislation has been enacted to prevent companies from making misleading environmental marketing (Hawkins, Uhera and Bay 2022).

Effective IT vendor and procurement practices are essential for leveraging your buying power. A recent survey by Coeus Consulting found that 90% of European IT leaders consider sustainability a “core IT objective.” According to the survey, this is also a recent change for nearly half of them (Coeus Consulting 2022). Furthermore, the survey states that very few IT leaders have started to make tangible progress and include IT sustainability requirements within their procurement process. Technology Leaders Agenda 2021, conducted by Tech Monitor, suggests that less than 40% include sustainability requirements in their procurement process (Tech Monitor 2021). This is a missed opportunity for leveraging your buying power to make a sustainable ESG impact.

The next section will examine what essential IT sustainability requirements you can leverage in your procurement processes.

Essential IT sustainability requirements

As we saw in the previous section, managing your vendors and IT procurement process poorly can introduce significant risk into your IT supply chain. Therefore, it is critical to make a significant step-change to include essential IT sustainability requirements. It is also essential that your IT procurement practices align with overall company sustainability commitments and which IT categories will have the most significant ESG and cost impacts. This may seem overwhelming initially, especially if you start from a blank sheet of paper. Fortunately, there are plenty of resources to draw a wealth of experience from, and simply introducing sustainability certifications from credible ecolabels for IT equipment such as Epeat, TCO Certified, and Energy Star will put you in a significantly better position toward a sustainable IT practice.

Sustainability certifications

The most common ecolabels for IT equipment are as follows:

Epeat

Epeat is a global type 1 certification. To be considered an “EPEAT,” registered products must meet specific required and optional criteria. They are evaluated against three levels of environmental performance – Bronze, Silver, and Gold. The product needs to be Epeat registered in the country of sale. Criteria areas include product longevity, materials selection, design for circularity, supply chain greenhouse gas emissions reduction, end-of-life management, energy conservation, and corporate performance.

TCO Certified

TCO Certified is a Nordic type 1 certification. They are a world-leading organization that provides sustainability certifications for IT products. They are an independent verification organization that provides a wide-range system of criteria and they provide a framework for IT hardware vendors to certify their products with a TCO Certified quality label. Criteria areas include social and environmentally responsible manufacturing, circularity, and hazardous substances.

Energy Star

Energy Star is a US certification focused on energy efficiency. It uses 25% to 40% less energy than conventional models by using the most efficient components and manages energy use better when idle. Labeled equipment is third-party certified to be energy efficient. Equipment with type 1 certifications also meet the criteria in Energy Star.

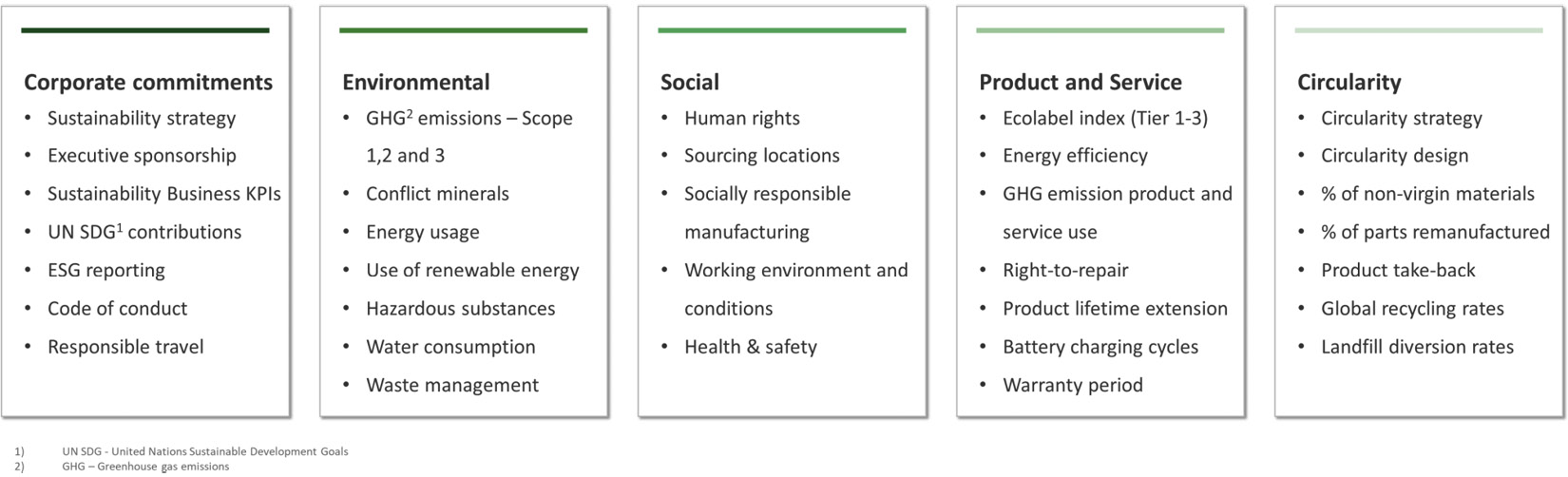

Let us take a closer look at what essential IT sustainability requirements could be considered part of your IT procurement and vendor management practice. We have outlined five key categories: corporate commitment, environmental, social, product and service, and circularity. Figure 8.2 outlines these five key categories and critical requirements to be considered. Let us look at each of these in more detail:

Figure 8.2 – Key IT sustainability requirements

Let us look at each of the five key areas in more detail.

Corporate commitments

When looking to engage with a vendor, it is essential to understand their corporate commitments to ESG. The following are some essential requirements you should consider from a corporate commitment perspective:

- What is your overall sustainability strategy?

- Describe your corporate governance and executive sponsorship for ESG.

- Do you have any sustainability business KPIs?

- Describe your contribution to United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

- What overall commitments have been made – that is, Science-Based Target Initiative (SBTi), exponential roadmap, and so on?

- What ESG reporting do you do – that is, sustainability report, carbon disclosure project (CDP), or something else?

- What areas does your code of conduct address – that is, antitrust, anti-corruption, boycotts, social, environmental, business practices, and ethics? Would your vendor be willing to sign your code of conduct? If they refuse to sign your code of conduct, will you take assertive action to exit the relationship?

- What is your policy on responsible business travel?

- Have you embedded sustainability KPIs into compensation packages and Management By Objectives (MBO) for all employees?

Environmental

This involves being a responsible company that focuses on minimizing the environmental impact on the planet. The following are some essential requirements you should consider from an environmental perspective:

- Reducing your indirect greenhouse gas emissions (Scope 3) should arguably be your most important IT sustainability objective to pursue. Therefore, it is critical to understand your vendor’s environmental impact from both an operation and a product and service perspective. You should understand how well your vendor commitments align with your sustainability commitments. How well do they deliver on their environmental commitments? Are they lagging or surpassing?

- Greenhouse gas emissions – scopes 1, 2, and 3.

- Use of conflict minerals such as tantalum, tin, and tungsten (3TG), gold, and cobalt.

- Energy usage.

- Use of renewable energy/share of renewable energy.

- Use of hazardous substances in products and manufacturing.

- Water consumption.

- Waste management in the supply chain and manufacturing.

Social

Being a purpose-led and socially responsible company is no longer optional. It is expected, and you should place the exact expectations on your vendor ecosystem. Putting rigorous requirements on your vendors regarding human rights, working environments, working conditions, health, and safety can bring about a change and make a significant social impact. This also ensures that your suppliers require similar behavior from their providers. Here are some essential requirements you should consider from a social perspective:

- Human rights, adherence to the International Labour Organization’s (ILO’s) eight fundamental conventions

- Human rights, adherence to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

- Socially responsible manufacturing

- Working environment and conditions – that is, adherence to labor law legislation, working hours, ergonomic and safe working conditions, evacuation routes, use of hazardous substances, and so on

- Health and safety protocols, workforce injury, casualties, illness rates, and so on

- Correct and transparent diversity, equity, and inclusion practices are also key

- For software providers, creating unbiased software is also critical

Product and service

In a fast-paced industry like Information and Communications Technology (ICT), unfortunately, it has become the norm to run through IT equipment well before it has reached its end of life in favor of a new, more shiny model just released on the market that is more efficient and faster with newer capabilities. Balancing different priorities such as technical specifications, employee experience, cost, and IT sustainability from different stakeholders adds complexity to the equation.

As mentioned in Chapter 6, IT Hardware Management, GHG emissions and e-waste have become major inhibitors in our net-zero race. As roughly 80% of GHG emissions are already consumed before they reach an end user, we must ensure extended product longevity. The following are some essential requirements you should consider from a product and service perspective:

- Demand Tier 1 eco-labeled and energy-efficient products

- GHG emissions from product and service use

- Right-to-repair

- Product lifetime extension – the ability to replace battery, memory, hard drives, and so on

- TCO Certified Accepted Substance List

- Warranty period

- Battery charging cycles

- Access to spare parts

- Ability to buy refurbished products

- End-of-life management

Sustainable IT requirements for products and services can become lengthy and require in-depth knowledge to place adequate and just requirements on your vendor. Fortunately, governing bodies such as Epeat, TCO Certified, and Energy Star can assist you on your journey toward sustainable IT procurement. This enables you to shift the heavy lifting from your procurement organization to the vendor to provide proof of compliance for a specific product within a product category. Instead of putting forth detailed requirements to your vendors, you can demand an Energy Star rating and TCO certification for a specific product category such as computers, monitors, tablets, and smartphones. It would help if you asked for proof of compliance with your existing IT equipment and when new products are released into a specific category. This allows you to verify, audit, and compare your vendor’s ICT equipment.

Circularity

As we have learned in previous chapters, we must transition from a linear to a circular economy. Infinite growth on a finite planet is not possible. As we learned in Chapter 1, Our Most Significant Challenge Ahead, we are already consuming 1.75 % of Earth’s resources, and we are not regenerating nearly enough to live within the constraints of planet Earth. Currently, the global economy is only 8.6% circular, leading to an extensive circularity gap (Circularity gap 2020). With 89% of organizations recycling less than 10% of their ICT equipment and the global e-waste approaching 60 million tons per annum, we need a massive shift toward circularity (Capgemini Research Institute 2021). To drive the shift from a linear to a circular economy, we need to leverage our buying power to put more demanding circularity requirements on our vendors. Here are some essential requirements you should consider from a circularity perspective:

- What is the company’s overall circularity strategy?

- Circularity design (design-out-waste) – how is waste designed in the product?

- % of non-virgin materials – how much non-virgin material is used in the product?

- % of parts remanufactured – what parts have been extracted and reentered in the manufacturing process?

- Product take-back – that is, what commitments does the vendor give to take back old equipment? What partners do they work with for IT Asset Disposition (ITAD)? What is the locality of these ITAD partners?

- Secure removal of information – what processes and procedures are in place to remove information securely before the IT equipment can be refurbished, repurposed, or recycled?

- Water sourcing – is the vendor applying innovative water sourcing strategies to preserve water?

- Global recycling rates – what are the global recycling rates?

- Landfill diversion rates – how much waste is diverted from landfills?

Now that we have looked at some of the essential IT sustainability requirements you can impose on your vendor in any IT procurement process, let us take a closer look at how to drive sustainable IT procurement from start to end.

Sustainable IT procurement from start to end

In this section, you will hear from Camilla Cederquist, Atea Sustainability Focus (ASF) manager. She will share her point of view on how you can create sustainable IT procurement from start to end. Atea is the largest provider of digital workplace solutions and IT infrastructure in the Nordics. Since 2017, Atea has been driving an initiative called Atea Sustainability Focus, which aims to accelerate the sustainable transformation of the IT industry by using the collective power of Nordic IT buyers.

When ASF was launched in 2017, social issues dominated the agenda, which was quite natural given the industry’s complex, global supply chains. Since then, however, buyers in Europe have shifted focus toward climate and circularity, whereas in the US and Canada, social issues are still the key focus. This means sustainability in IT procurement is no longer a question solely for the purchasing department. Increasing product lifespan, for example, must involve both the IT department and the users.

These are just some of Atea’s findings. They focus on small IT products for office use and circularity and environmental sustainability since this has been top of mind for the Nordic market in the past couple of years.

IT procurement today

Within the ASF, we conduct a yearly survey where Nordic (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden) IT buying organizations communicate their priorities and headaches around sustainable IT. In the survey, 639 professionals within IT, sustainability, and procurement responded from primarily large organizations with more than 500 employees and roughly an even split between the public and private sectors.

From the survey, we can see that there is room for improvement regarding how sustainability is incorporated into purchasing practices. Even though the majority claim that IT sustainability is a high or very high priority, 25% do not specify any sustainability requirements on suppliers. Still, respondents are aware of the power of using procurement muscle to drive sustainability, as 18% say creating and reinforcing a process and internal collaboration around sustainability requirements is the most important thing they can do to contribute to more sustainable IT.

The main challenges that have remained on top during all the years that we have conducted the survey are as follows:

- It is challenging to measure the effects

- It is challenging to obtain information about and compare the sustainability performance of different solutions

- There’s a lack of time and resources to follow up on the requirements

From this, we can conclude that IT buyers need more support and feedback from the industry regarding comparability and effects and that purchasing and follow-up processes need to become more efficient. Next, we will offer some advice on how that can be done.

Create a market for sustainable IT

There is nothing more powerful than using the business muscle to drive change. In our dialogues with the IT industry, we hear that customer demands are the primary catalyst. The most important thing is to weigh sustainability into the purchasing decisions – in other words, do not buy based on price alone. Make sustainability count! And be transparent about how and in what way you will premiere the sustainability efforts of your suppliers.

When many buyers act in unison, the effect will scale. A group of IT-buying organizations, such as H&M, Ikea, and Electrolux, are engaged in an ASF-founded network – Leadership for Change – where all members have vowed to make sustainability part of every IT purchasing decision. By collaborating, they have been able to identify good examples – measures that have been proven successful – that they are now turning into best practices for others to adopt. Some of the things they found will be covered here.

Being sustainable is smart

There is a common yet unfounded narrative that sustainability drives cost. That is a very narrow view. Instead, smart thinking often affects both costs and sustainability positively. For example, members found that devices with ecolabels are often of higher quality. When a device has reached its end of use, once funneled through the ITAD process, the devices tend to get a higher residual value and can be put back in circulation.

Instead of routinely supplying employees with extra peripherals such as dual monitors, docking stations, keyboards, computer mice, and backpacks, it should be standard practice to make the employees order what they need.

Sustainable IT is not always about sustainability

How you design your workplace can have a significant impact on sustainability. Using a widescreen monitor instead of two smaller ones could cut carbon footprint by around 30% (IVL Svenska Miljöinstitutet 2020). Screens with built-in docking stations and devices with standardized connectors (USB-C) are other examples of how a workplace can be designed to be more resource efficient. The sustainability impact of these choices is not always apparent to those in charge of making these decisions. For organizations with serious ambitions around sustainable IT, it is key to involve people from the IT, sustainability, and purchasing functions in the purchasing process and design purchasing policies and strategies.

Creating a market for sustainable IT is extremely important to drive IT sustainability further and it requires focused concerted efforts from both the buying and the selling sides to make sustainability part of every IT procurement decision. In the next section, we will take a closer look at how we can address some of these hotspots.

Address the hotspots

IT procurement can never be sustainable unless it addresses the main challenges of the IT sector. Despite this, we tend to focus on details such as specific product characteristics or the concept of repairability, even though we have no intention to repair the device if it should break down. Let us look at some findings from an analysis of circular procurement that was done within the ASF initiative.

Do a double materiality analysis

How you approach sustainability when purchasing IT products should be based on a double materiality analysis: what issues are most material to you, and what issues are most material for the industry to address? Where they intersect is where you should focus. For example, cutting emissions from transportation may be material for your organization. Transports, however, are just a small part (about 3%) of the carbon footprint of a small IT device. Therefore, if you focus on demanding sustainability criteria on transport in your IT purchasing, the impact on sustainability in the IT sector will be negligible, and you miss the opportunity to make a difference.

Find common ground

Sometimes. you may feel that the sourcing organization and the supplier are adversaries, where the customer demands things that the supplier is reluctant to meet. Another approach can be to look for common ground. More often than you think, the suppliers want the same thing as you do. They, too, want to reduce their climate impact and increase their resource efficiency. Use this as a starting point. This way, you co-create solutions that meet your needs and help fulfill your ambitions around sustainable IT.

Let us look at an example where this was not the case. One public IT-buying organization in the Nordics put a requirement in the request for tenders that the devices were to be delivered without peripherals. Later, it turned out that the peripherals were still produced but unpacked along the way, hence not delivered to the customer. The requirement was fulfilled, but the underlying ambition – to be more resource efficient – was not.

Start from the end

80% of the carbon footprint of a small IT device comes from production, meaning the “debt” is there even before you open the box. Therefore, the most important purchasing decision isn’t about supplying IT devices; it’s about ensuring they are recovered after use. So, when you buy, buy circular! See to it that there is a process and a plan for returning the devices once you have no use for them anymore so that they can be reused and, later, recycled (and remember, end of use is NOT end of life).

Do not get lost in the details

As mentioned in the preceding sections, product requirements tend to get very detailed around, for example, battery charging cycles, access to spare parts, recycled material, and the desired absence of certain chemicals. One Nordic site that lists circular requirements for IT products prides itself on having more than 70 (!) sustainability requirements. They are probably all relevant and provide value, but if not all buyers decide to unite behind one of them (like the world did to eliminate the use of freon in the 90s), there will likely be little or no effect. For maximum impact, we need to focus on models for sustainable consumption, such as Product-as-a-Service (PaaS), where the supplier retains ownership of the devices and therefore is incentivized to keep them running for as long as possible.

1990s Freon refrigeration chaos

The 1990s was a decade of refrigeration chaos due to the usage of freon, primarily in refrigerators. This led to the depletion of the stratospheric Ozone layer. In 1987, a historic treaty named the Montreal Protocol was signed by 24 countries under the United Nations Environmental Plan. The original protocol called for the reduction and eventual elimination of a class of compounds such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). Upon signing the Montreal treaty, the refrigeration industry took immediate steps to reduce these compounds and by the end of the 90s decade, 95% of refrigerators containing these compounds had been phased out. This is a good example of what swift and effective policymaking we require on a global scale going forward to curb the climate crisis.

The process

The procurement process often focuses on product requirements and responsible manufacturing. A lot can – and needs to – be done before we get to this stage. The most sustainable product is the one you already have – or never purchased.

Numerous standards and frameworks guide more sustainable IT procurement. In Chapter 6, IT Hardware Management, you were introduced to the 9R framework. We will revisit the framework and add IT procurement requirements to each step. Remember, the more of the top boxes you fulfill, the more resource efficient (and thus less strenuous on the environment and climate) you are. Instead of focusing on buying the most sustainable product, ask yourself, do we need to buy anything at all? Can we circulate equipment internally instead? Do we need to buy new equipment? And do we have to buy it, or can we rent it? After all, it is not the product itself we need; it is the functionality it provides.

Figure 8.3 illustrates a three-step process with procurement guidelines for more sustainable IT procurement you can implement to become more resource efficient:

Figure 8.3 – Sustainable IT procurement – a three-step process

Need for product – remove and reduce (need)

- Can we increase the contract’s length?

- Can internal assets be circulated (repaired or upgraded)?

- Can we remove/reduce the need for certain products, such as peripherals or docking stations?

Purchase is required – reuse and recover

- Consider as a service? (optimized product supply and closed loop.)

- Buy refurbished products

- Close the loop (make sure the product is recovered already at the point of purchase)

Purchase of a new product is required – reduce (harm) and recover

- Consider as a service? (optimized product supply and closed loop.)

- Buy eco-labeled and “high-spec”

- Close the loop (product is recovered after use)

- Include extra warranty

- Buy repairable products

At every step of the process, you can make sustainable decisions to minimize your impact. Enable yourself to make informed decisions. How much does the IT we buy cost from a life cycle perspective? Use a tool for calculating the total cost of ownership to identify the best solution for your organization from a sustainability and financial perspective. Would it, for example, be more efficient to buy more high-spec devices with longer lifespans that can be circulated internally and entail a higher residual value, even though it might cost a little more at the point of purchase? What would it mean to buy reused devices? Challenge your suppliers! Communicate your ambitions and struggles and let them come to you with the solutions. Why not get inspired by the Dutch Sustainable Public Procurement (SPP) Criterial Tool (https://www.mvicriteria.nl/en/webtool?cluster=1#//7/1//en), where the supplier is required to describe how the contract at hand will contribute to a circular economy. A better plan is rated higher. The UK Public Sector has created a Greening Government ICT and Digital Services Strategy and has also enacted a 12-point Technology Code of Practice to increase sustainability throughout the life cycle of technology: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greening-government-ict-and-digital-services-strategy-2020-2025.

The ABC for sustainable IT procurement

When you finally reach the purchasing stage, it is essential to ensure the most sustainable products are bought from the most responsible suppliers. By doing just three (relatively simple) things, you can build a sustainable base for your IT procurement without having to be a sustainability expert or allocate a lot of resources to formulate, verify, and follow up on requirements. This easy-to-implement list of actions is part of Atea’s Guide to Sustainable Procurement of IT:

The RBA is the world’s largest industry coalition on sustainability that gathers all major IT brands as well as several of their sub-suppliers. Full and regular RBA members are committed to following a shared code of conduct, regularly conducting third-party audits in their supply chain, and actively contributing to correcting any deviations.

- Buy eco-labeled equipment.

Type 1 ecolabels set comprehensive sustainability requirements throughout the product life cycle that are verified by a third party. Therefore, you do not need to have expertise within these areas or allocate resources for a follow-up.

- Include take-back clauses in agreements.

Is end-of-life (or rather end-of-use) a purchasing matter? Indeed it is! Build a 1:1 relationship with your devices by requiring the supplier to take back sold products. Even though you may have separate suppliers for the supply and take back, make sure you have a plan for the product’s end-of-use phase when it is purchased. Chapter 6, IT Hardware Management, in the IT Asset Disposition section, we covered how to give end-of-use products a second life.

ABC – that is how easy it is to get started with sustainable procurement of IT!

Now that we have looked at how we can drive sustainable IT procurement from start to end, let us take a closer look at how to set up a sustainable IT vendor management practice to drive value and reduce risk.

Sustainable IT vendor management

Now that you have learned about some of the sustainable IT procurement requirements you can impose on your vendors and how you can drive the process from end to end, let us look at the broader perspective and how to work with sustainable IT vendor management. Vendor management is the discipline of managing, administering, and guiding product and service vendors in an organized way to drive vendor behavior and optimize IT or business outcomes. The vendor management discipline emerges once a contract has been signed with a vendor. However, given the vendor classification, the vendor may or may not fall within the scope of vendor management.

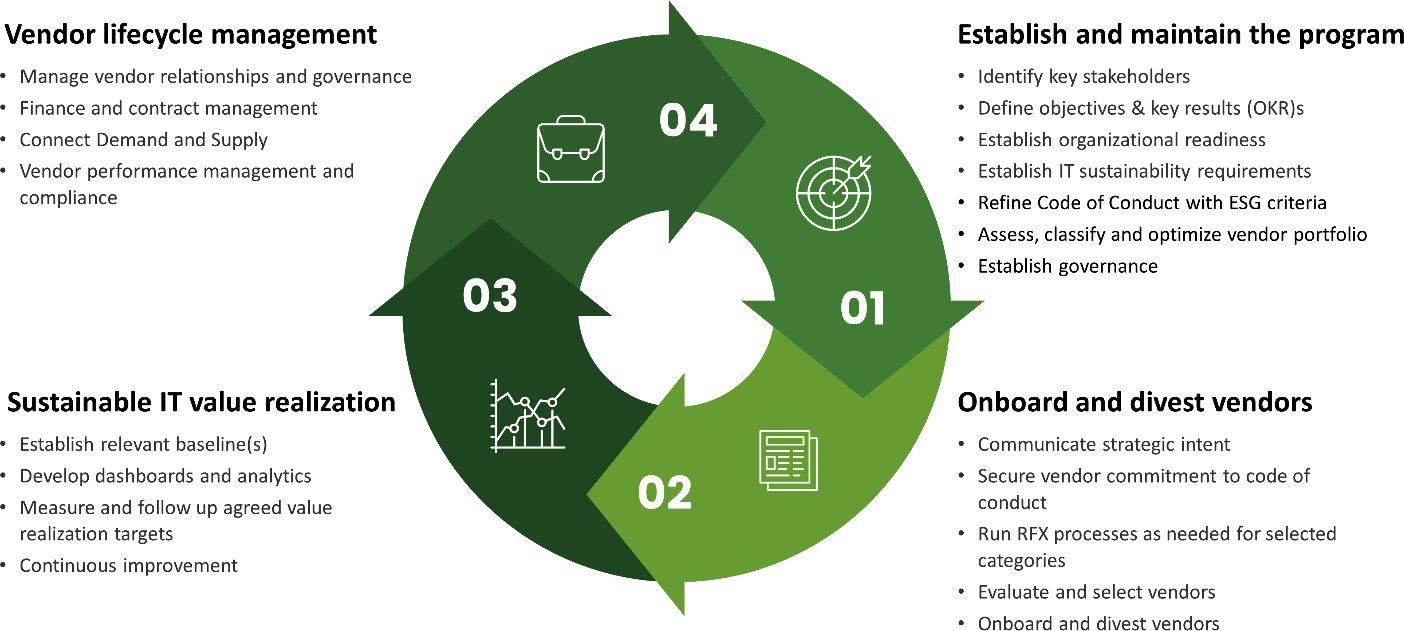

A typical vendor management function is often challenged to unlock business value beyond incremental cost savings. As we have seen in previous chapters, software and hardware vendors comprise a large portion of scope 3. As more services are moving to the cloud, scope 3 emissions will continue to increase unless they are managed effectively. New regulations are emerging, such as the European Union’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) directive, where you have to account for your own Scope 1 and 2 emissions and your Scope 3, which includes your entire IT Supply Chain. It is time to start asking your vendors the tough questions. They may not be able to respond to your inquiries about your scope three emissions, but in due course, they will be forced to disclose these numbers. Therefore, setting up a sustainable IT vendor management program is critical to driving purposeful change and delivering sustainable business outcomes. Let us look at a four-step process on how to establish sustainable IT vendor management.

Step 1 – establishing and maintaining the program

Identify key stakeholders, and work with key stakeholders to define objectives and key results (OKRs) and establish organizational readiness. Establish IT sustainability requirements for your product and service categories and use readily available resources instead of starting from a blank sheet of paper. Refine your code of conduct if needed and include ESG criteria. Benchmark your code of conduct with sustainability industry pioneers. Assess your existing vendor landscape. Classify them into vendor categories, such as strategic, tactical, emerging, and legacy. Based on your classification, determine how you should optimize your vendor portfolio and decide which vendors should be part of the sustainable IT vendor management program.

Step 2 – onboarding and divesting vendors

Once you have established your program, you should communicate your strategic intent with your vendors. Early on, you should secure vendor commitment to your code of conduct. It is essential to be clear about your expectations and show vendors what they need to do to match your criteria. Ask difficult questions and expect granularity. For example, are your vendors using carbon credits, and are you willing to accept that? Give them time to change but be clear on what the consequences would be if they fail to meet those terms and the roadmap.

Run Request for Information (RFI), Request for Quote (RFQ), and Request for Proposal (RFP) as needed for selected categories. Evaluate and select vendors. Finally, onboard and divest vendors as needed.

Step 3 – sustainable IT value realization

Establish relevant baselines such as yearly GHG emissions from Scope 1, 2, and 3, energy usage, yearly purchases of assets in the ICT category, hazardous substances, and refurbished and recycled assets through IT asset disposition. Once a baseline has been established, develop dashboards and analytics to measure and follow up on agreed value realization targets. Establish a process for continuous improvement based on findings.

Step 4 – vendor life cycle management

The final step is to manage the entire vendor life cycle management from end to end. Business demand needs to be connected to the vendor on the supply side, and performance management and compliance must be followed up continuously. Vendor governance needs to be established at a strategic, tactical, and operational level, and relationships must be managed at each corresponding level.

Figure 8.4 illustrates a four-step vendor life cycle management process. It covers how you start establishing and maintaining the program to how you manage the vendor throughout their life cycle:

Figure 8.4 – Sustainable IT vendor management program

Now that we have explored the process of establishing a sustainable IT vendor management program, in the next section, we will take a closer look at how to set up a vendor management sustainability scorecard.

Vendor management sustainability scorecard

Now that we have gone through the different levers of how you can leverage your buying power through IT procurement and vendor management, let us take a closer look at how you could construct a vendor management sustainability scorecard.

At an overall vendor management level, you should include critical measurements such as performance, contract, relationship, and risk. In addition to that, you should add a sustainability category. The sustainability category can also be divided into the following three specific categories:

- Vendor performance: Overall vendor sustainability performance in strategy, commitment, and progress. What is the footprint?

- Technology as an enabler: The specific impact provided by product and service use. What is their handprint?

- IT for Society or Technology for good (TECH4GOOD): The use of technology to effect positive social benefits through technology adoption. What is their heartprint?

The sustainability scorecard may also look slightly different based on the IT procurement category. It is not the same as measuring IT hardware manufacturers, software providers, professional services, or telecoms. Each has different sustainability strengths, weaknesses, and focus areas.

If you just want to get an initial read on some of your vendor’s net-zero ambitions, https://zerotracker.net/ is a great place to start. They provide an overview of the 2,000 largest publicly traded companies in the world by revenue. Figure 8.5 provides a summary of the major ICT companies and when they aim to fulfill their net-zero ambitions or whether they have already fulfilled them:

Figure 8.5 – Net-zero ambitions of major ICT companies

It is worth noting that at the time of writing, I was unable to find any net zero ambitions from some of these prominent technology companies: Automatic Data Processing (ADP), Alibaba, DXC Technology, HCL Technologies, Tencent Holdings, China Mobile, Gartner, International Data Corporation (IDC), International Data Group (IDG), Splunk and Tesla Motors. Hopefully, this will change in the future.

Now, let us look at some specific sustainability scorecards for different IT procurement categories.

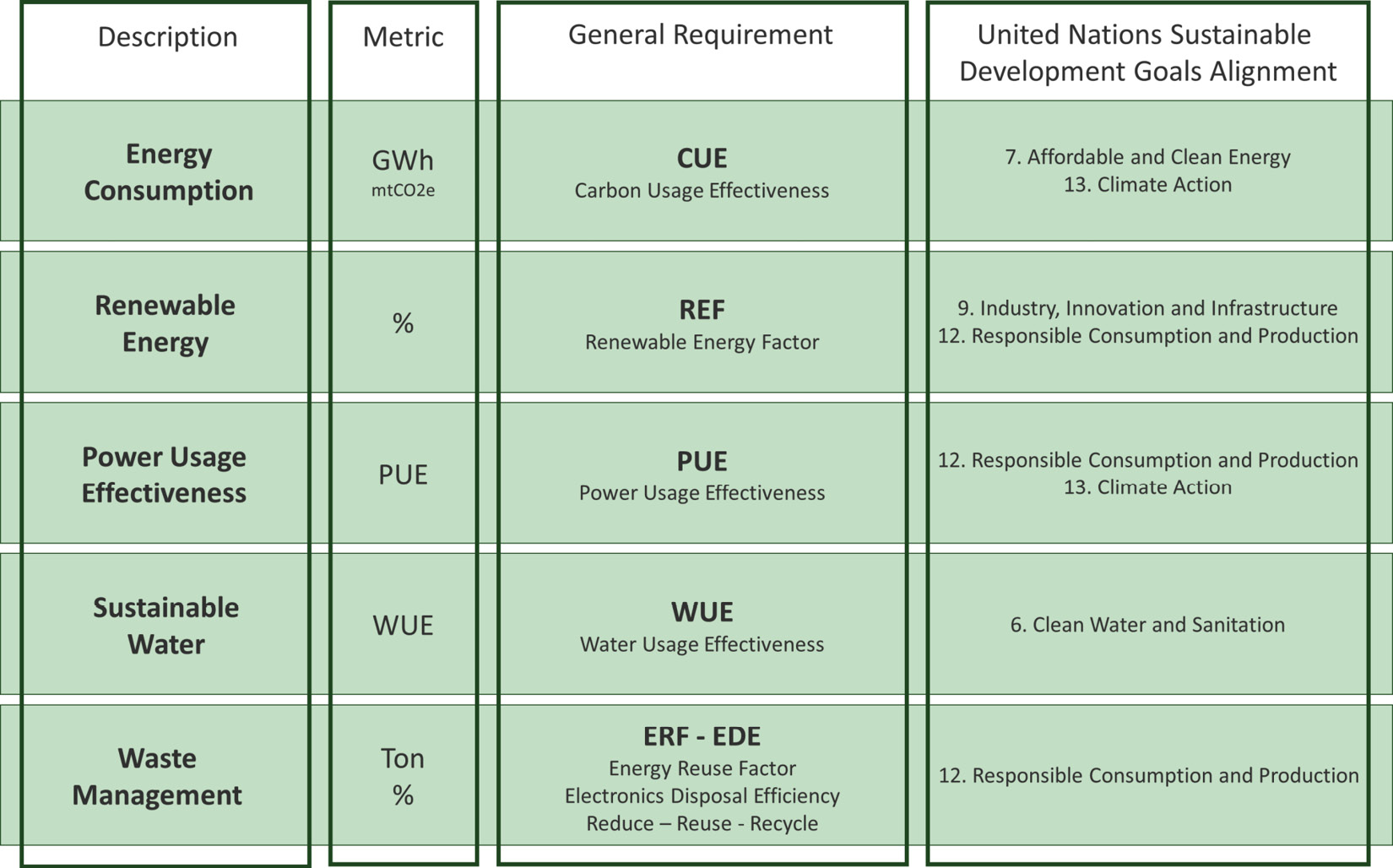

For data center and cloud providers, the data center sustainability scorecard from Chapter 4, Data Center and Cloud, as illustrated in Figure 8.6, is a good place to start. The EU guidelines for sustainable data centers are also very comprehensive (https://e3p.jrc.ec.europa.eu/communities/data-centres-code-conduct):

Figure 8.6 – Data center sustainability scorecard

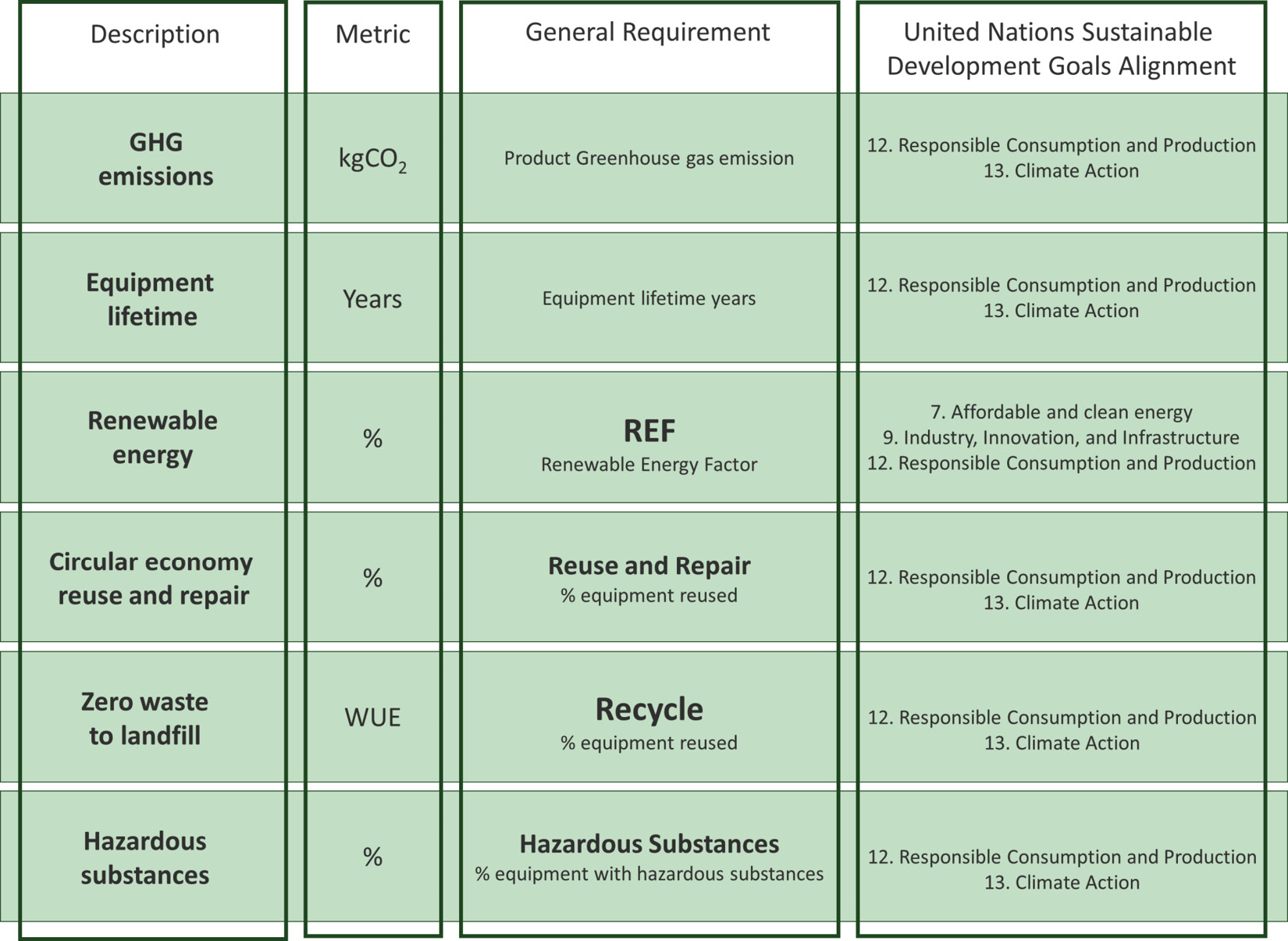

For IT hardware vendors, the IT hardware sustainability scorecard from Chapter 6, IT Hardware Management, as illustrated in Figure 8.7, is a good place to start:

Figure 8.7 – IT hardware sustainability scorecard

For a professional service firm that you work with, simply tracking the GHG emissions per project, be it via a product or individually, may be enough. For example, if you engage a vendor to run your IT service desk, it may be enough to understand what the GHG emissions are for the service provided by the vendor if they have committed to your code of conduct.

Tracking all these KPIs for reporting purposes from your vendors may seem overwhelming. Still, if you set up a systemic way to collect the data from your vendors through standardized formats and APIs, the process should be much smoother and streamlined.

For you to provide accurate disclosure of your own Scope 1, 2, and 3 GHG emissions, the Scope 3 emissions from your product and services – technology as an enabler – and of your vendors would be a great start. With the increased usage of cloud services such as Microsoft Office 365, Salesforce, and ServiceNow, understanding your Scope 3 from using these services is highly relevant. Not all vendors will be able to provide you with an accurate figure of what the yearly GHG emissions per user are, for example, for using Microsoft Office 365 or Salesforce Sales cloud. Still, it would help if you started asking the tough questions. Once more customers start asking these questions, the vendors will be poised to do accurate calculations and provide you with the data. Some vendors have gotten further along on their journey than others.

Summary

Now that we have reached the end of this chapter, you should have a better understanding of what the drivers for sustainable IT vendor management are and how you can leverage your buying power in your IT supply chain to make it more trustworthy and transparent. Secondly, you should know what essential IT sustainability requirements can be leveraged in your IT supply chain from a corporate commitment, environmental, social, product and service, and circularity perspective. Thirdly, you should understand how to drive sustainable IT procurement from start to end. Just leveraging three simple steps can make your IT procurement much more robust and sustainable. Furthermore, you should understand how sustainable IT vendor management can impact ESG change in your entire vendor ecosystem if managed well. Finally, you should be armed with crucial sustainability metrics that could be leveraged by your vendors to maximize ESG impact, minimize risk, and reduce cost.

The following are some of the key recommendations that you should apply to leverage your buying power:

- Make your purpose and intentions clear with your vendors. Find a common ground with your vendors to make a joint ESG impact.

- Choose vendors that are members of the Responsible Business Alliance.

- Update your code of conduct with impactful ESG criteria and ensure your vendors subscribe to it.

- Leverage existing sustainability certifications from Epeat, TCO certified, and Energy Star and place the burden on the vendor to provide proof of compliance.

- Buy eco-labeled equipment.

- Include take-back clauses in agreements.

- Demand disclosure of GHG emissions from not only the vendor but from their product and services, which can be included in your Scope 3 reporting.

- Leverage your buying power to manage our vendor ecosystem, and acquire and divest vendors based on their performance as needed.

In Chapter 9, Sustainable by IT, we will look at how technology can be leveraged to provide sustainable solutions in various industries.

Further reading

To learn more about the topics that were covered in this chapter, take a look at the following resources:

- ASF Leadership for Change: https://www.atea.se/atea-sustainability-focus/leadership-for-change/

- Clean Electronics Production Network: http://www.centerforsustainabilitysolutions.org/clean-electronics

- Dutch Sustainable Public Procurement (SPP): https://www.mvicriteria.nl/en/webtool?cluster=1#//7/1//en

- Epeat: https://www.epeat.net/

- Energy Star: https://www.energystar.gov/

- European Union Green Public Procurement: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/gpp/index_en.htm

- European Union Data Centres Code of Conduct:

- https://e3p.jrc.ec.europa.eu/communities/data-centres-code-conduct

- UK Public Sector: Greening Government ICT and Digital Service Strategy

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greening-government-ict-and-digital-services-strategy-2020-2025

- International Labor Organization – Eight Fundamental Conventions: https://www.ilo.org/global/standards/introduction-to-international-labour-standards/conventions-and-recommendations/lang--en/index.htm

- Responsible Business Alliance (RBA): https://www.responsiblebusiness.org/

- TCO Certified: https://tcocertified.com/

- TCO Certified Accepted Substance List: https://tcocertified.com/industry/accepted-substance-list/

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

Bibliography

- Capgemini research institute. 2021. Sustainable IT - Why it’s time for a Green revolution for your organization’s IT. Capgemini research institute.

- Circularity gap. 2020. Our world is now only 8.6% circular. CGR. Accessed March 04, 2022. https://www.circularity-gap.world/updates-collection/circle-economy-launches-cgr2020-in-davos.

- Coeus Consulting. 2022. CIO and IT Leadership Survey 2022 - The critical role of technology leaders in delivering on sustainability targets. Accessed June 13, 2022. https://f.hubspotusercontent10.net/hubfs/3969064/CIO%20&%20IT%20Leadership%20Survey%202022%20-%20Coeus%20Consulting.pdf?hsCtaTracking=702ec559-7a9a-4dd2-972d-bbbbd1cc4731%7C90eceb9c-6dd4-42b1-b891-8688d1b0dd70.

- Kirchherr, Julian, M.P. Hekkert, and Reike Denise. 2017. “Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions.” Researchgate.net. September. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320074659_Conceptualizing_the_Circular_Economy_An_Analysis_of_114_Definitions.

- Tech Monitor. 2021. Technology Leaders Agenda 2021. Accessed 06 13, 2022. https://techmonitor.ai/whitepapers/technology-leaders-agenda-2021.