Enviable growth

So what is India like today? India is one of the top four economies in the world. Growing at over 6 per cent annually, India is the second fastest growing free market economy in the world (second only to China), the largest democracy and is the third largest base for scientific and technical manpower. It has the potential to become the world’s largest economy and grow faster than China. To put this into perspective, even now, China and India together comprise barely one-third of the United States in terms of GDP. At high growth rates their journeys over the next 40–50 years will be fascinating, full of opportunities and pitfalls. India’s engine of future growth has been turned on and not surprisingly it is being powered by globalisation and more recently by innovation. In the more long term, however, growth will be sustained through innovation and entrepreneurship. By sheer size, scale and impact, India leads the charge in innovation because of historical, geographical and demographic advantages.

While assuming the often derided status of the world’s back office, India has been quietly setting its house in order. Globalisation has not only provided the capital that has carved out a rising middle class in India but it has blossomed a new breed of entrepreneurs, giving India access to know-how and technology and the competence that make competitive economies tick. The Indian consumer is also ready for action. Most Asian success stories have involved the government forcing its people to save, producing growth through capital accumulation and market-friendly policies. In India, growth is being driven by enterprising individuals, ranging from vegetable vendors in the villages, to family boutiques in the town to the high-flying entrepreneurs in the cities.

By 2006, India knew how to market itself and capture attention. Slogans such as ‘Incredible India’, ‘the world’s fastest growing free market democracy’, and ‘India everywhere’ were no longer mere marketing soundbites. An outsider will need perspective to decipher what is incredible, what a freemarket and democracy can do and cannot do when it has the second largest population in the world. People can relate to the theme of India far better because India’s ubiquity gives it the rare distinction (along with China) to populate towns of their own in other countries, be it India town in Singapore, Brampton in Toronto or Dallas in the US. India has become a pervasive and global phenomenon.

Coming away impressed by the show India put on at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2006, Newsweek’s International Editor Fareed Zakaria wrote an article entitled ‘India: Asia’s Other Superpower Breaks Out’.1 He wrote, ‘Each year there is a star. Not a person but a country. No country has captured the imagination of the conference and dominated the conversation as India in 2006.’ What he saw in Davos beyond Indian extravaganza, colourful Indian shawls, chicken tikka and Bollywood songs served on iPod shuffles to every delegate was a resolve from within the country to rise from the ashes and dominate the world.

I represent the first generation of young working Indians who have tasted economic freedom – India’s second independence from its own stifling economic policies. This generation has been part of a revolution that is taking the country to its next level. With less than 5 years of working experience in the new India, my generation would earn within months what their parents earned in their life time. For most people of my parent’s generation, owning a house was a retirement dream. For my generation, owning a house even before starting a family was not just a distant possibility but a norm.

‘The individual is king’, writes Zakaria. ‘Urban India is bursting with enthusiasm. Indian businessmen are excited about their prospects. Indian designers and artists speak of extending their influence across the globe. Bollywood movie stars want to grow their audience abroad from their base of half a billion fans. It is as if hundreds of millions of people have suddenly discovered the keys to unlock their potential. Young Indian professionals don’t wait to buy a house at the end of their lives with their savings. They take out mortgages. The credit-card industry is growing at 35 per cent a year. Personal consumption makes up a staggering 67 per cent of GDP in India, much higher than China (42 per cent) or any other Asian country. Only the United States is higher at 70 percent.’

So what does the scoreboard look like? The economy has posted an average growth rate of about 6–7 per cent in the decade since 1997, and reduced the numbers in poverty by about 10 per cent. India achieved 8.5 per cent GDP growth in 2006, 9.0 per cent in 2007 and 7.3 per cent in 2008, significantly expanding manufacturing through late 2008. India also is capitalising on its large numbers of well-educated people who can speak English well to become a major exporter of software and business process services. Strong growth combined with easy consumer credit, a real-estate boom, and fast-rising commodity prices fuelled inflation concerns from mid 2006 to August 2008. Rising tax revenues from better tax administration and economic expansion helped New Delhi make progress in reducing its fiscal deficit for three years before skyrocketing global commodity prices more than doubled the cost of government energy and fertiliser subsidies.

Liberalisation breaks ground for Entrepreneurship

Economic liberalisation achieved two things – it broke the ground for private entrepreneurship, and it opened opportunities for manpower and talent that was ready to occupy jobs created by the new wave. Suddenly hope had wings. Everyone will agree that the change has not been enough. The need to propel the country towards economic and growth leadership is now more urgent than ever.

Liberalisation impacted different companies differently. For new companies, dramatic growth was achieved more quickly. For the country’s largest private sector firms, it strengthened diversification and international ambitions. For educated individuals, it created great new jobs. For entrepreneurs, it launched them into new industry. Today, Indian companies are not only cash-rich but have ambitions to become global. According to The Economist, Indian companies announced 115 foreign acquisitions, with a total value of $7.4 billion, in the first three-quarters of 2006.2 Even in 2008, the slowest year for Indian M&A overseas, 1270 deals with Indian participation of $50 billion were executed. During the first three quarters of 2009–10 (April-December 2009), 2984 proposals amounting to $14.3 billion were cleared by the Reserve Bank for investments overseas in joint ventures and wholly owned subsidiaries.

Take the Tata Group for example. The Tata Group runs more than 100 companies and is a useful yardstick for India’s industrial and post-industrial economy. Tata is the country’s largest business house, and a far-flung conglomerate that makes everything from tea to cars, sells everything from steel to consulting, and has a footprint in chemicals, communications and IT, consumer products, energy, engineering, materials, and services. Two of its largest operations are steel making, through Tata Steel, and vehicle manufacturing (Tata Motors). Tata Tea is one of the largest tea producers in the world and owns the esteemed Tetley brand. Incidentally, Tata Motors is the planet’s youngest carmaker, beginning in the 1990s when global car makers were shedding jobs in a highly commoditised Japanese-dominated market. Tata Steel acquired Corus Group for $13.6 billion, which created the sixth-largest steel company in the world. The Tata Group made an even bigger splash with the 2008 acquisition of Land Rover and Jaguar from Ford. Tata pumped $1 billion worth of R&D into these ailing car brands. In 2007, the group crossed the $50 billion mark, half of which accrued from its overseas operations. The Tata Group provides just one example of a global Indian conglomerate. At the other end of the spectrum are new industry segments that have appeared from nowhere. For example, the automobile-parts business is made up of hundreds of small companies in India. Four years ago the industry’s total revenues exceeded $10 billion. The turnover of the auto component industry is estimated to touch $19.2 billion in 2009–10. In 2008, General Motors alone imported over $1 billion of car parts from India. It also benefits from India’s large car market. That’s globalisation.

In keeping with the trends, earlier in 2009, General Motors entered into a joint venture with Reva, a Bangalore-based company that makes the G-Wiz electric car, which has proved popular in the UK. The new vehicle has now been road-tested and can run for up to 200 km without recharging. GM is seeking to produce affordable electric cars in India using Reva’s technology and GM’s manufacturing capacity.

India’s automotive industry is a sunrise industry that didn’t exist 15 years ago. So too are India’s pharmaceutical and IT industries. The growth story so far, and to an extent in most cases even today, is deeply rooted in globalisation – globalisation that is characterised by capital inflows, technology and process transfers in exchange for access to a billion consumers, talent and cost competitiveness. Liberalisation also saw multinationals returning. When I began reporting for the Indian Express, Abhishek Mukerjee was Country Manager of Compaq in India. He sat in an 18-feet by 18-feet rented room in a business centre, just opposite to the Indian Express building in Bangalore and next to Hewlett Packard’s offices. That office had a couple of desks, a vase of wilting flowers, one telephone, one fax machine, a computer and an executive assistant. This was Compaq’s national operations. Compaq’s then global CEO Eckhard Pfeiffer was challenging IBM in the desktop business. Compaq shared such prestige when it came into India and operated through Indian distributors such as Microland. When Compaq moved to its own bigger offices in Du Parc Trinity in Bangalore, a press conference was called. A new office building was breaking news. It meant business was good. It meant Compaq was there to stay. It was newsworthy because it wasn’t easy for private companies to bear wings so quickly. When a company set up a new communication link there was a press conference. A $1 million investment hit the headlines. With the eviction of IBM and Coca Cola from India in 1977 by the Janata Party Government still fresh in the minds of people, the return of competitive global corporations was like the return of Siberian cranes. It meant promise.

How has globalisation worked for India? By opening up its large market, India has helped competitive nations improve their returns to productivity in two ways. By offering a lower cost base, India became attractive to competitive nations, allowing them to transform their operations. India also lowered the thresholds for high paying jobs for less skilled employees in developed nations. In turn, the value of goods and services produced in India as measured by the price they command in open global markets and the efficiency with which India produced these goods and services ensured that Indian companies were able to support higher wages and achieve attractive returns, leading in turn to a higher standard of living for its people.

Why Innovation is critical to sustain growth

As much as there is a link between globalisation and national productivity, there is a link between innovation and national productivity. Although substantial gains can be obtained by improving institutions, building infrastructure, reducing macroeconomic instability or improving human capital, all these factors eventually seem to run into diminishing returns, and the same is true for the efficiency of the labour, financial and goods markets. In the long run, standards of living can be expanded only with innovation. Innovation is particularly important for economies as they approach the frontiers of knowledge, and the possibility of integrating and adapting technologies originating from outside tends to disappear. Innovation is also linked to productivity as it contributes to new products and new markets that command higher value and provide new ways for firms to produce goods and services faster, better and cheaper. For firms, innovation drives differentiation in their products and services thereby increasing the value of goods and services or drastically lowering the cost of production.

The key challenge for India is to create conditions where its firms and people can upgrade their productivity through innovation. India thus needs to set in order a number of fundamental pillars. For example, it is difficult for innovation to prosper without institutions that guarantee intellectual property rights. Innovation cannot happen with a poorly educated and poorly trained labour force. And it is difficult to sustain innovation with inefficient labour and financial markets or without an extensive and efficient infrastructure.

Assessing a country’s competitiveness is difficult because of the sheer number and variety of influences on national productivity and is clearly one that is outside the scope of this book. For our purposes, we will depend heavily on work that has been published in this area by the World Economic Forum (WEF), in particular relating to its global competitiveness index. Popular literature3 indicates that national prosperity can be measured by the productivity of an economy, which is measured by the value of goods and services produced per unit of a nation’s human resources, capital resources and natural resources.

Harvard’s Michael E. Porter, the Bishop William Lawrence University Professor, who also heads the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness (ISC), makes a fundamental assertion that as the world economy is not a zero-sum game, many nations can improve their prosperity if they can improve productivity. Improving productivity will increase the value of goods produced and improve local incomes, thereby expanding the global pool of demand to be met. Porter and his team are behind the framework that the WEF uses to rank nations on their global competitiveness.

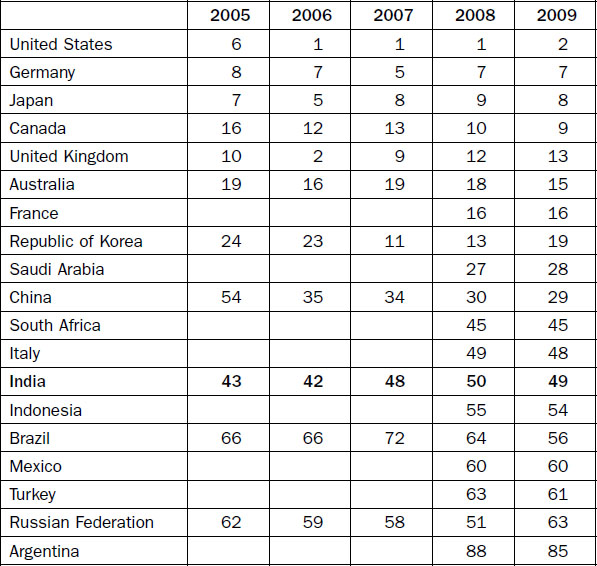

In its global competitiveness report for 2009 (Table 4.1), the WEF placed Switzerland, the US, Singapore and Sweden as the world’s most competitive nations. Interestingly, the top four nations share the top 10 global ranks in higher education & training and innovation. They score very high on market goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, institutions, infrastructure, technology readiness and business sophistication. The US has an inclusive market. Switzerland, Singapore and Sweden do not have very high GDPs. The implications are that the three latter countries are some of the world’s largest tax payers. But Switzerland, Singapore and Sweden also have some of the world’s best institutions. There is therefore a strong correlation between a nation’s competitiveness and its higher education & training, innovation, and the quality of its institutions.

Table 4.1

Global Competitiveness Index comparisons of G20 countries: India needs to close the competitiveness gap

Source: World Economic Forum Reports, G20 analysis by the author. Table excludes the European Union.

We see a similar pattern if we compare the BRIC nations with the world’s most innovative nations. First, the BRIC nations are among the top 10 markets in the world. India has very favourable rankings in its financial market sophistication, business sophistication and innovation, indicative of innovation-led growth. But India needs to improve both primary and higher education and training to provide the high quality of talent it needs as much as it needs infrastructure and labour reform.

Much academic work focuses on a minimum set of root causes that statistically explain the differences in current prosperity levels across countries. However, a WEF report notes that there are a number of factors that may not be econometrically efficient in predicting the competitiveness of nations. For example, a nation’s colonial past, influence of history on policy, country size and population, inherited natural resources, geographical location, or a large home market all affect prosperity. Inherited prosperity from, for example, oil resources

Much academic work focuses on a minimum set of root causes that statistically explain the differences in current prosperity levels across countries. However, a WEF report notes that there are a number of factors that may not be econometrically efficient in predicting the competitiveness of nations. For example, a nation’s colonial past, influence of history on policy, country size and population, inherited natural resources, geographical location, or a large home market all affect prosperity. Inherited prosperity from, for example, oil resources needs to be assessed for parity. Such revenues from natural resource exports lead to an appreciation of the real exchange rate that, in turn, drives factors of production into local activities such as retailing that have lower long-term potential for productivity growth. An additional justification for the resource curse is the role of institutions: natural resource wealth has a negative effect on the quality of political institutions and economic policy, eroding competitiveness over time.

A country’s geographical location is often discussed as a possible external factor influencing wealth. Location can affect the ease with which countries can engage in trade, for example, because of having a long coastline, or because of distance from large markets. Another locational dimension is the proximity to the equator and climatic conditions that expose a country to tropical diseases and might lead to lower agricultural productivity. Similarly, although there is little empirical evidence on the direct effects of country size on growth, there is evidence of the greater effect of openness to trade on prosperity for small countries than for large countries. Further analysis of these factors is beyond the scope of this book.

Evidence for innovation-led competitiveness

By the end of India’s 10th five-year plan (2006), globalisation has already kick-started innovation-led competitiveness, but at a small scale within companies, within departments, within research labs and within its universities. Today, innovation is a theme deliberated in boardrooms and shop floors alike. Everyone from the multibillion Indian corporations to the florist who exports flowers to Europe is thinking of differentiation and protecting that differentiation using intellectual property protection.

I lived in north-east Bangalore for over 14 years. It took a while before I noticed a two-storey building in the corner of a busy, dusty, chaotic intersection in Kalyan Nagar, an eastern suburb of the city. All that captured my attention was the single security guard who kept watch while occasionally chasing dogs or cows that strayed into the company compound. This was the key operation of GangaGen, which has raised close to $9 million in three rounds of venture funding. Founded in 2000 by J. Ramachandran, GangaGen4 is engaged in product lines that are aimed at treating antibiotic-resistant infections such as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus). The surroundings may be odd for a biopharmaceutical R&D company focused on the development of novel therapies for medical, veterinary, agricultural and environmental applications, but GangaGen already has several patents in its area of research and has operations in Canada and the US.

A few years ago, I was on a panel discussion with Srini Rajam at an innovation conference hosted by Microsoft. Srini headed Texas Instruments’ Indian operations for a time. Srini was then running his own company, Ittiam Systems, founded on 1 January 2001 to focus on digital signal processing (Ittiam stands for ‘I think therefore I am’). Rajam told me that Ittiam was already licensing its IP on DSP and ASIC designs to DSP chip manufacturers around the world. Successes of companies like Ittiam come from the identification of the right space to work in (i.e. DSP assemblies), a business model that is built on a licensing approach where profitability comes via volumes and IP delivery via reference designs. A business model based on licensing revenues from IP created in the embedded electronics space is new and different from the traditional services model that India is known for. Ittiam represented a new stream and highlighted maturing of the Indian technology story.

Clearly there are two waves that are converging in the making of modern India’s growth engines. The first is from the globalisation that capitalised on the liberalisation policies of 1991 to drive growth primarily through exports. This growth provided new avenues, scale, infused knowledge and capital to develop new opportunities for sustainable exports. Even as the first wave continues to drive growth, a second wave is emerging less conspicuously – one that is primarily driven by the need for new products and services for both the domestic and the international market. The second wave is driven by Silicon Valley-type entrepreneurship in the organised sector, and small-scale entrepreneurship typified by thousands of simple vending operations with the result that innovation has a much larger agenda.

The emergence of India’s software industry is a good example of the first wave led by globalisation as Ittiam Systems is for the second wave. The software sector grew exponentially during the Y2K era at the end of the last millennium. In the 1990s much of the Indian industry aligned itself to rewriting legacy code to meet Y2K requirements. This was largely straightforward. Thousands of Indian engineers scoured for date-related code in millions of cobol and mainframe code written in the 1960s–1980s and fixed it, and they did a good job. The Y2K experience brought into the industry strict standards of quality, compliance and discipline required to engage in international trade. Unlike other industries, the ‘raw material’ consumed in this industry was people, so there was an unparalleled infusion of knowledge into the industry within a country that already had fertile engineering minds.

In the years following Y2K, the Indian software industry not only branched out from that firm foundation of quality and global delivery infrastructure to offer other services in system integration, infrastructure management, testing and business process outsourcing; it also did a better job than the large players of the time such as IBM, EDS, CSC and Accenture who were more rigid in their approach to IT outsourcing. The Indian software industry perfected the art of cost variability by building the dynamic resourcing capabilities for large multinationals that were stuck in vendor-locked contracts with IBM, EDS, Accenture and CSC.

Initially compelled by necessity to comply with the demands of international trade and later as a necessity to compete effectively at home and abroad, globalisation also brought in structural changes in the way companies ran their operations. For example, many of the industries that were protected under the Licence Raj now had to compete not only with global competitors but also with other Indian firms that began to produce high-quality products and services both for local consumption and exports. The first of the changes adopted by local manufacturing industries and software was adopting stringent quality standards. Quality was not a pressing need under the Licence Raj.

In tandem with the software revolution, after GE pioneered the ‘back office to the world’ concept in India, the business process outsourcing industry took off. GE’s $300 million annual savings resulting from its operations in India made global corporations sit up and take notice. GE in fact woke India up to its own latent potential: a large number of educated, English-speaking, employable graduates obsessed with continuous improvement. This has created an industry that, like GE, strives to live the ‘Six Sigma way’ every day. A Six Sigma wave swept through India’s services community.

The unwritten story of India’s prowess in software services was that it disrupted the business models of large IT professional services players such as IBM, Accenture, EDS and CSC. In the end these vendors began emulating Indian vendors by setting up large operations in India, to the extent that when IBM’s Lou Gestner turned around the elephant (by his own admission) to focus on services, he placed one in every six IBM employees in India. IBM Global Services, its services arm, ensured that 25 per cent of its workforce – around 60,000 people – operated on a global delivery model out of India. Accenture followed suit and by 2010 had 50,000 people in India. IBM bought Indian capabilities through acquisition of companies like Daksh, as did EDS by acquiring Mphasis, an Indian company.

The other thing Indian industry collectively did was to ensure that the software it developed was second to none in quality. By the time the Y2K scare died down after the turn of the millennium, 60 per cent of Indian companies were rated SEI CMM Level 5, the highest standard a software company can achieve. By 2003, there were 80 software centres worldwide assessed at CMM Level 5, 60 in India. The trigger to this need for quality was the idea that exports to Europe were unthinkable without an ISO certification in the late 1980s and 1990s. The real impetus came after Motorola’s software centre at Bangalore became the world’s second CMM Level 5 unit in 1994 (the first was at NASA). Wipro became the world’s first PCMM (People-CMM) Level 5 organisation. As of 2003, of the world’s nine CMMI-assessed companies worldwide, eight were in India. (The only non-Indian CMMI-assessed organisation was Lockheed Martin Management & Data Systems.) The old India prior to 1991 neglected quality. For the new India quality became an obsession. Manufacturing companies were similarly affected. For example, today India has the largest number of FDA-approved pharmaceutical manufacturing plants outside the US.

Much before the Y2K bonanza, not far from Motorola’s office on Ulsoor Road in Bangalore was another company, Texas Instruments, that foresaw the potential of engaging Indian engineers to drive its design and R&D centre. In fact, Texas Instruments was the first company to recognise India as a base for software as far back in 1985. What started out in Cunningham Road as a small operation of about 100 people eventually became one of Texas Instruments’ largest R&D centres outside the US. By the time Texas Instruments celebrated its 20th anniversary in India in 2005, Bangalore alone had 100 R&D centres that came up as investments from multinational corporations. India now has over 400 R&D centres operated by multinationals and another 600–800 Indian R&D centres. One report5 stated that of 186 of the world’s largest corporations, 70 per cent of new R&D centres over the next three years will be in India or China.

Y2K jump-started the software revolution. Quality sustained it. Core R&D moving to India offered the recognition for India’s intellectual capital. Today, Texas Instruments’ Bangalore operation caters to the demands of the entire Asian region, and is integral to building everything from cell phones to DSPs for the consumer electronics industry.

Cost, quality and time to market revolutionised India’s software industry, allowing globalisation to take roots. And once cost competitiveness, skills and quality were in place, businesses grew and an ecosystem to sustain the growth in terms of institutions offering computer education and training, certification authority, and specialised recruitment firms snowballed in.

Many today brush aside the quality story as statutory. Rightly so. But at the time this was big deal for India and the industry. It set the industry apart. Amidst the chaotic environment surrounded by the sea of ‘non-quality’, there were hundreds of world-class organisations in the software, systems engineering and business process outsourcing areas that epitomised excellence. Operationally these companies worked as well as or even better than their global counterparts. When they were operationally competent, location, distance and the time difference no longer mattered. In fact the time difference proved to be a distinct value proposition for US firms who leveraged the global delivery model by taking advantage of the ‘follow the sun’ model of 24:7 global access to a team of world-class engineers. Experts, Judy Bamberger for one, attribute India’s meteoric rise in quality standards to the spirit of its people that she characterises as passion and bringing their heart to the workplace together with their problem-solving skills and flat organisation structures.

India’s obsession with quality and the era that signified it epitomised the desire and appetite for efficiency and improvement. The American companies Indian companies worked for also had a positive influence on shaping Indian management styles to foster meritocratic and flat organisations with high levels of performance ethic. Much of India’s part in globalisation involved efficiencies of cost driven by doing things better. This era established the foundations of an innovation mindset in its working population.

I attended a CII (Confederation of Indian Industry) quality summit in 1994 where Philip Crosby, widely regarded as the main proponent of the zero defect programme in quality, was the keynote speaker. Much as the Indian industry sang to the tunes of ‘zero-defect manufacturing’ at this conference and thereafter, within a decade Indian industry was hungry for more innovation in product quality. At the peak of these structural shifts, I met Venu Srinivasan, Chairman and Managing Director of TVS Suzuki at a corporate function. Srinivasan was modernising TVS Suzuki at that time and had just bought hundreds of seats with CAD/CAM software and was reconfiguring his production line. Srinivasan told me that zero-defect manufacturing was outdated. For more than a decade, Srinivasan worked hard to sustain his competitive-edge manufacturing motorcycles and scooters in a joint venture with Suzuki Motor. By 2001, TVS Motor had become strong enough to split with Suzuki on favourable terms and start manufacturing on its own as TVS Motors. This was not without reason. Having emerged from protectionism in the early 1990s, Indian companies needed technology transfer to bridge its technology deficits quickly but once they gained strength from their joint ventures, foreign partners were no longer needed. In return, Indian partners gave their foreign partners a deep understanding of the Indian market and many ventured on their own.

The motorcycle market in India is fiercely competitive. TVS Motors stood behind Bajaj Auto and a distant third from Hero Honda despite the resilience the company displayed more than once in the past. As the Indian market matured, competition was now not on the basis of who the technology partner was or what the marketing strategies were but on product differentiation and on intellectual property. In February 2009, the Economic Times reported that a local court restrained TVS Motor Company from making and selling the 125-cc Flame bike.6 TVS Motors’ rival Bajaj Auto had sued the company. Bajaj Auto claimed that a patent it owned was used in the production of the motorcycle. Competition based on intellectual property is now more prevalent. For many of India’s manufacturers, for a long time, it has been very difficult to break from the focus on making incremental improvements to making successful product breakthroughs.

Six years after I met TVS’s Venu Srinivasan, I was in the audience listening to Anand Mahindra, Vice Chairman and Managing Director of the Mahindra Group, another leading car-maker. Anand was speaking about competitiveness at a Gartner summit in Mumbai. Anand attributed the success of Mahindra’s flagship car, Scorpio, an SUV that quickly captured a market that didn’t exist in India, to an innovative inventory management system which has also drawn inspiration from how food hawkers make chats in Mumbai’s Chowpatty beach. According to him, inventory management was like making bhel puri or masala puri: you don’t know what the demand was at any point of time yet you need access to all the right ingredients. Decisions on storing the right quantities of puffed rice, sev, onion, tomatoes, turmeric, potatoes, salt, chili powder, and green and sweet chutney are therefore important. They also need to be at an arm’s length so that the chat maker’s arm can move across the various ingredients in the right order to create the right flavour for the customer. In the chat business freshness, speed and variety are vital; such is the complexity of the inventory management required to make tractors, SUVs and car parts that Mahindra exports today. To Anand Mahindra, innovation is about applying one discipline to another and India is doing exactly that in many of its burgeoning industrial sectors. Mahindra tells the audience: ‘What hits the sweet spot in the consumer’s mind is a great product. And a great product need not be a Rolls-Royce.’ India’s domestic market does not need a lot of RollsRoyces at the moment but it needs affordable cars to meet the demand of the population and the terrain. Anand Mahindra’s firm acquired the consulting firm whose founders had originally developed SAP’s inventory management module, strengthening Mahindra’s core competence in local manufacturing. Armed with these capabilities, companies like Mahindra focus on producing high-quality products for local needs as well as exports.

I trained as a reporter at the Indian Express, one of the largest and most aggressive newspaper networks at the time. In the process, I met the businessmen and entrepreneurs who shaped India’s IT industry that put India on the global map.

When I met Infosys’ then CEO, Narayana Murthy, in 1995, the company had just moved to its own campus on Hosur Road in Bangalore. Aptly the buildings we met in are now called the Heritage Building as it was only one of the two buildings Infosys then had – and the pride of its founders. Infosys had just become the first Indian company to be listed on NASDAQ. Infosys today has over 60 multistorey buildings on the same campus, complete with world-class conference rooms, boardrooms, a helipad, a multi-level car park that uses RFID (radio-frequency identification) technology to identify its patrons, and a bus station for its employees that would dwarf even the state road transport corporation in terms of efficiency. Little did I know at the time that Infosys would become India’s poster child of private entrepreneurship and reform. I also didn’t know that six years later, I would work as a researcher in the R&D labs of the company that Murthy had started 20 years earlier.

For those who graduated in time to enter the workforce, economic liberalisation offered a new found sense of purpose. Many people, especially younger people, broke away from the public sector in search of meritocracy, entrepreneurship and an environment that saw the profit motive as a legitimate means of creating and sharing wealth. Infosys demonstrated for the first time in India that wealth could indeed be both created and shared legitimately with those who created it. Infosys became one of the first Indian companies to introduce an employment stock option programme. When the programme was in force, desk clerks and non-technical staff had the potential to achieve economic parity which was nearly impossible in most companies, to the extent that a colleague at Software Engineering and Technology Labs, where I was R&D Manager, had immortalised one of the Infosys founders in a framed picture among the gods.

Samson David is now a senior executive at Infosys running a sizeable part of its US business. Samson is one among many successful professionals who form India’s 375 million middle class, many catapulted to that status as a result of globalisation. Before Samson joined Infosys in 1992, he shared an upbringing of many boys and girls of a generation that had no hope. ‘A generation that would be stuck in their situation with no future to look forward to’, Samson wrote in a recent email. ‘Infosys was instrumental in changing the future for many of those boys and girls – like me and also their families. Infosys gave us hope, opportunity, raised aspirations and made us dream of infinite possibilities.’ It is not that previous generations did not work hard. Samson’s father worked 12 hours a day, 6 days a week for many years but when he retired, his salary was just Rs 3500 (less than $100) a month. Samson believes that Infosys gave him more than he ever deserved, dreamed or desired. India’s private companies were platforms for creating wealth and took millions away from subsistence living.

For many in my generation who entered the workforce of successful private enterprises after 1991, the question of food on the table, a home and basic necessities were addressed early in life. The new work ethic in India even emulated American style excesses. I remember in 2000, requesting sick leave to take care of Teddy, my German Shepherd, who was suffering from separation anxiety as I had left him alone. At that time, our 29-year-old VP in charge of strategy had a pet python herself.

Ambitions for startup companies have varied. For many, like Mahindra, it was local leadership and global leadership. For others like Infosys, it has always been about global competitiveness and building lasting corporations. India now had the wherewithal, amidst its poor infrastructure and chaos, to launch a brand new future. Despite the stray dogs and cows sharing the scenery, there is access to capital and knowledge and there is the ability to attract the best talent. New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman called this levelling of the playing field, the flattening of the world. Globalisation did indeed flatten the world for India, setting the stage for it to compete squarely and fairly.

1.Zakaria, F. (2006) India: Asia’s Other Superpower Breaks Out, Newsweek, March 6, 2006, accessed February 2010, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/11571348/site/newsweek/print/1/displaymode/1098

2.‘India’s Acquisition Spree’, The Economist, 12 October 2006.

3.Porter, M. et al. Moving to a new global competitive index, The Global Competitiveness Report 2008–2009, chapter 1.2, p. 44. World Economic Forum.

5.Stuart, E. (2007) Move over China – Indian investments have the real potential, Money Week, 10 January, http://www.moneyweek.com/investments/stock-markets/move-over-china---indian-investments-have-the-real-potential.aspx

6.http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/News/News_By_Industry/Auto/Two-wheelers/Madras_High_Court_restrains_TVS_from_selling_125_cc_Flame_bike/articleshow/2788533.cms, accessed July 2009.