Enhancing rural GDP through inclusive innovation

Innovation is the specific instrument of entrepreneurship. The act that endows resources with a new capacity to create wealth.

In the 20 years since economic liberalisation, India’s economy has more than doubled, but the lot of the poor has remained largely unchanged. The number of children under 5 who are malnourished has dropped by just one point in the past 10 years, to 46 per cent, and although per- capita income – an inexact measure in a country with so many poor and so many rich – has doubled to about $1000 a year, inflation has eaten away at that gain. In spite of India’s much vaunted IT revolution, the sector employs not more than 10 million people. Although this figure is outstanding by any measure – accounting for half of Australia’s population – in the Indian context it is a trickle.

Besides agriculture, India’s biggest employer is still the textile industry,1 where workers (often women and children) toil in sweatshops that produce clothes and shoes for the West. The question is how to bring in a multiplier effect to double or triple rural GDP – a term that has been resounding in my interviews for this book. The other term that has resonated is scale. Rural GDP and scale are not mutually exclusive. How can the nation expand its knowledge economy in a way that is socially inclusive as well as internationally competitive? Innovation cannot become the whim of the elite before it becomes a need of the public. The conflict is between minds and mindsets, minds representative of enormous talent and creativity and mindsets reminiscent of the baggage Indians carry from the country’s past. I once heard social activist Aruna Roy2 say that the days of finding solutions from outside the system are over, and that solutions themselves will come from the people once they are empowered.

By that definition grassroots innovation is about providing the right platforms for people to find solutions to their own problems.

A discussion on innovation cannot exclude rural development. Inclusive innovation must be driven by rural development. And rural development has to be anchored in alleviation of poverty. The desired impact has to be specific, measurable and time-bound. For example, a focus on moving 250 million people who live on under a $1 a day to $5 a day is a good start; $10 a day would be laudable.

R. A. Mashelkar served for over ten years as the Director General of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) until his retirement in December 2006. Mashelkar is the architect of the National Innovation Foundation, which engages rural innovators across the country and has a database of 100,000 innovations that resulted from the creativity of rural Indians for rural India. He points out that Tata’s Nano is not just a small car, but the symbol of a resurgent India driven by a focus on innovation and engineering that is dedicated on more for less for more people. He calls this Gandhian engineering. When the CSIR rewrote its mission statement, it said its mission is to ‘provide scientific industrial R&D that maximizes the economic, environmental, and societal benefits for the people of India’. And it does this to some extent. For example, CSIR’s Central Leather Research Institute (CLRI) developed a method of silver sulfadiazine microencapsulation on collagen-based biomaterials. Although the CLRI was ostensibly a ‘mundane research institution’, it specialised in the science of collagen and had come up with remarkable systems for healing burn injuries.

In one of his presentations, Mashelkar makes mention of an affordable solution for drinking water. He cited the application of a process for the preparation of ultrafiltration membranes of polyacrylonitrile, using malic acid as an additive. This was the subject of a 2005 US patent based on precipitation volumisation, a unique technique allowing the creation of 20-nm pores that had been developed at India’s National Chemical Laboratory, one of the CSIR’s 40 labs. It had resulted in devices able to filter not only bacteria but also viruses from drinking water at a cost of one-tenth of a cent per litre. More than 2000 of these filters were deployed for hand pumps in rural villages that did not have electricity.

India’s development model lies in participative development, and empowerment. Sometimes even the government stepping back helps to provide its disadvantaged people with the infrastructure and tools to come up with their own solutions rather than deliver canned solutions from Delhi, a boardroom or a laboratory.

India’s masses are quick to reject initiatives that do not work for them. At the same time, India needs to ensure that its national resources are pooled to focus on uplifting areas that weigh progress down.

Take the bottom up view of health care in India. Very high numbers of deaths are reported from malaria, Japanese encephalitis and tuberculosis. These diseases are bigger killers than AIDS. But there is no coordination between establishments, research organisations, labs, pharmaceutical companies, public institutions, NGOs and the healthcare system to address them. A coordinated framework should include identifying the challenges and issues from which solutions and initiatives can be developed and supported by aligning resources to develop the solutions and deliver them.

From an innovation perspective, someone has to define a portfolio of health areas that need fundamental research. Someone has to think about funding these projects and ensuring that the right portfolio gets the right funding. Someone else has to think about rolling it out with a focus on last-mile deployment. Someone else needs to think about the training, delivery, staffing and education around it. This is highly complex. The need is overwhelming enough for the concerned parties to take a coordinated approach. This is precisely why the nation needs a critical research portfolio, a portfolio prioritisation mechanism and a portfolio balancing mechanism. I believe such a mechanism should be placed under an innovation agenda that ties in the funding, resourcing and collaboration framework that I discuss in the next chapter.

In the context of a developing country in transition such as India, innovation can provide a channel to both increase growth and reduce poverty. By applying knowledge in new ways to production processes, more, better or previously unavailable products can be produced at prices that all Indians can afford. This model is not value-based production of goods and services as in developed economies, but one based on production of goods and services for utility and volume consumption at affordable prices. Innovating for utility and volume is drastically different from innovating for value and the results can be disruptive. Public policies to enhance pro-growth, high-volume innovation include improving access to higher education, training, certifications and creating new public-private partnerships as well as pursuing broad economic reforms that create the appropriate environment for investment in and the commercialisation of research. At the same time, bolstering inclusive innovation includes efforts to harness creative efforts for the poor, to promote, diffuse and commercialise grassroots innovations, and to help the informal sector better absorb existing knowledge.

Innovation need not be disruptive technology or the process-related innovation that the developed world has come to believe as mainstream; it can be incremental, or social innovation focused on the last-mile rural problem in India.

The government is doing much to access the last mile. The ambitious national ID programme is one such example of an unprecedented attempt to wire 1 billion citizens into an electronic network that can track their development and upliftment. No single government has undertaken a task as huge and complex as this. Uniquely identifying a citizen doesn’t solve all the problems associated with populist programmes such as NREGS but it will solve some.

Programmes such as the NRHM and NREGS are moving large amounts of development funds to rural India. They are bringing in the processes, changes in mindsets and empowerment to rural economies. India now requires solutions at the last mile to meet the huge demands of change. For example, to curb corruption and create transparency many states have begun using hand-held devices to reduce manual errors, ensure disbursement of receipts and to reduce manual bookkeeping that is prone to much error, loss and traceability.

The government’s appointment of Nandan Nilekani, former co- chairman of Infosys, is seen as a serious effort to root out inefficiencies in the system. Many believe that Nandan’s hub and spoke model – where the issuance of unique ID numbers is centrally managed while adding citizens to the database is done at one of the thousands of registries identified for the purpose – will root out duplication of citizens’ records, build credible identity and establish transparency on how government funds are spent on its citizens. With the unique ID, the issuance and managing of job cards in the NREGS context will become much easier and relatively free from fraud, enhancing the visibility of individual recipients within the system.

An inclusive innovation portfolio

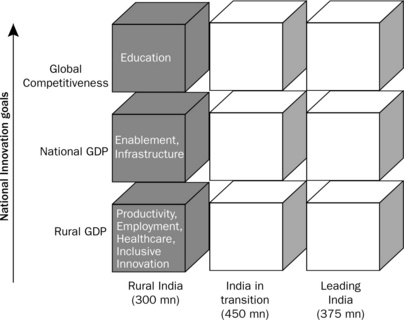

What would a portfolio for inclusive innovation look like? The national innovation framework that is proposed in this book has three national economic priorities, namely growing rural GDP, growing national GDP and sustaining global competitiveness (Figure 8.1). The framework also highlights the need to meet specific developmental goals of India’s poorer sections of society in order for them to transition into the middle class while contributing to rural and national GDP growth.

Grassroots innovation works (and needs to be strengthened) in a country as large and diverse as India. This includes innovations for an environment that is characteristically Indian. These inventions are probably difficult to migrate from India’s socio-economic, political, demographic and cultural context to that of other countries, but they are critical to how Indian ingenuity can be directly used to transform its circumstances, in ways that elite corporate research laboratories never can. For example, a Guragaon-based mobile phone company recently launched a low-cost handset that uses commonly available AAA-sized batteries aimed at the hundreds of millions who live in areas where power supplies are erratic. Priced at around $35, Olive Telecommunications’ ‘FrvrOn’ – short for ‘forever on’ – sports a rechargeable lithium-ion battery common to mobile phones, but also has a facility to include an AAA, dry-cell battery. This adaptation may not be welcomed with enthusiasm in a developed market but with more than 10,000 Indian villages that have no access to grid electricity, and many more places that suffer power cuts, such simple adaptations go a long way.

Rural and indigenous innovations come from two sources: first, farmers, and the semi-literate or illiterate slum-dwellers who have managed to change things by marrying their own innate genius to their understanding of conditions on the ground; and, second, innovations taken from more traditional sources such as universities and independent engineers that are then adapted to suit Indian traditions and conditions.

For example, Deepak Rao in Chennai conceived a solar water harvester using solar energy to convert non-potable water into potable water, an important contributor to rural health. The product, which is still being developed, can produce up to 5 litres of water per day from a 1-m2 model. The product has much promise in solving the shortage of drinking water globally. Rao has received a grant from the Techno entrepreneur Promotion Program of the Department of Science and Technology of the Government of India.

Balubhai Vasoya, from Ahmadabad in Gujarat, developed a stove that uses a six-volt electric coil to heat kerosene, converting it to gas which burns with a blue flame. The stove saves 70 per cent on fuel compared with conventional stoves running on liquid petroleum gas (LPG), at the same time delivering the benefits of LPG – no odour, no smoke or soot – all at Rs 1.5 (less than 5 US cents) per hour. Vasoya’s contribution alleviated the respiratory conditions of many rural women who are otherwise dependent on hazardous firewood or pressure stoves.

Anna Saheb Udgave is a 70-year-old farmer from Sadalga village in Karnataka’s Belgaum district. Udgave developed a low-cost drip irrigation system to fight a water crisis in his village, and this has now been developed into a mega sprinkler called the Chandraprabhu Rain Gun. This sprinkling system, a perfect example of an innovation that can improve agricultural productivity, is now being used in southern Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka.

Rao, Vasoya and Udgave are rural innovators who have simple solutions that enhance rural productivity and solve problems that are unique to their communities and those that are most critical to their survival and development. The end goal of nurturing rural innovation is not always a patentable idea but rather sustainable development. Some steps needed for rural development can be rudimentary. Some villages in India just need a good motorable road. The people already know what to do with their own lives once they have a motorable road. This is Aruna Roy’s point on enabling local populations to find their own solutions. Once there is a road, there is access to centres of economic activity. Labour, capital and produce can flow easily thereafter. There is a marked difference in the economic status of those villages with roads and those without roads.

Consider, for example, the Lijjat Papad story. Lijjat Papad is a food processing cooperative that produces papads, a fried appetiser made of rice or wheat flour. Lijjat papads are world famous among people of Indian origin, but originated from a cooperative institution started by seven housewives on a rooftop. On 15 March 1959, they gathered on the terrace of an old building in a crowded south Mumbai locality and rolled out four packets of papads to sell. The ‘seven sisters’, as they are fondly remembered, started production with the princely sum of 80 rupees ($1.25 at today’s prices), borrowed from a good Samaritan. The women’s cooperative became one of India’s most successful business ventures and has since diversified into bakery products, detergents, spices and flour. It has built an image as one of trusted homemade products of the finest quality at very reasonable prices, employs 45,000 women and has a revenue of US$100 million. Lijjat Papad celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2009.

Another example of rural process innovation that resulted from unique needs in India is the well-documented tiffin delivery network that operates in urban and suburban Mumbai. The delivery network, comprising 3500 dabbawallas (the local term for tiffin carriers), provides 150,000 lunch boxes to citizens in Mumbai each day. What is appealing about the process is that it matches the process efficiency and accuracy ratings of global giants like General Electric and Motorola according to Forbes – fewer than one error per million deliveries. Such standards emerging from an illiterate workforce are truly outstanding and commensurate with the acclaim it is receiving as a case study for process innovation in campuses as far afield as the United States. Much of the acclaim goes to the coding system devised by which each dabba (tiffin box) is marked with indelible ink with an alphanumeric code of about 10 characters. In terms of price and the reliability of delivery compared with the system used by Federal Express, for example, the dabbawallas remain unbeatable.

Innovation alone will not solve the rural GDP problem. The approach has to be a combined effort. Innovative solutions generated by rural populations themselves and those delivered to the ‘bottom of the pyramid’3 from outside will help but for sustainable rural development and elimination of poverty, these measures need to be sustained with at least three basic ingredients – access to education for all, access to health for all and a means to create wealth for every household or regular employment. Innovating in such an environment requires both passion and compassion.

India’s inclusive innovators

There are researchers, scientists and engineers already engaged in such efforts. Not many conversations on rural innovation in India fail to mention Ashok Jhunjhunwala, a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chennai, who has contributed to rural technologies and the telecommunications revolution in India. The rural ATM is one of his contributions. When standard ATMs cost around $20,000 each, convincing banks to install one in every one of the 650,000 villages in India would cost $13 billion. Jhunjhunwalla created a low-cost ATM ($1000) to work in rural conditions.

Rita tells me that she is asking banks to install one of these ATMs for the village administration and villagers to access NREGS funds. Today it is a day’s task to go to the nearest town on foot (sometimes as far as 10 km) to fetch the NREGA pay. Often the labourer forgoes a day’s wage to do this. Middlemen swoop on such opportunities. When the labourer authorises a middle man, he loses up to Rs 20 out of every Rs 100. A rural ATM that can withstand heat dust, and runs on solar power is available but such machines work on smart cards. But a biometric solution exists to overcome this problem. Once the banks, ATM hardware providers and rural development authority can show a business case and develop a win-win opportunity for everyone, this can be implemented en masse. Herein lies the need for a coordinated innovation framework that has a national scale and a geo-locational application yet ties in with the rural development goals. Coordination of challenges and problem solving is the key.

Professor Jhunjhunwala also heads a spinoff from IIT Chennai (Madras) called the TeNet Group. The TeNet Group has a vision to increase rural India’s GDP. This vision drives innovation coming from its umbrella companies. Some of the innovations from this team are adaptations of existing technology to provide data and voice connectivity for rural conditions often characterized by frequent power outages and harsh conditions. These have been incorporated in low-cost exchanges, low-cost service delivery, medical diagnostic equipment and ATMs.

One of the operations under TeNet is the Rural Technology and Business Incubator (RTBI). RTBI provides an incubation eco-system, mentorship, support, infrastructure and preliminary funding to entrepreneurs at any phase in their venture. In other words, RTBI’s mission is to design, pilot and incubate sustainable business ventures with a specifically rural focus. One example of RTBI’s contribution is DesiCrew, a rural business process outsourcing company, which sets up IT-enabled service centres in rural areas to employ and train local people to meet the back-office demands of regional clients.

Like TeNet and RTBI, Chennai-based Villgro4 is engaged in identifying and making rural innovations marketable and thus promoting rural prosperity. Villgro has had a role in incubating and supporting DesiCrew in its scaling up process. Through incubating rural innovations into businesses, Villgro has a key role in creating a network of different innovation ecosystem players. Formerly known as the Rural Innovations Network and started by Paul Basil, Villgro began as a network that uses multiple network agents such as Chennai’s engineering colleges, agricultural universities, research institutions, patent offices, local fairs, exhibitions and banks to identify innovations. Basil’s organisation then undertakes market research and refines the products for market friendliness by means of engineering overhauls. In most cases, the innovator passes on the technology to an entrepreneur or a company for a royalty. Villgro remains an enabler, providing consulting inputs to both innovators and entrepreneurs to tie up loose ends.

The National Innovation Foundation (NIF) is the other agency helping to build respect and partnership for innovators. NIF recognises the innovations by grassroots innovators, be they farmers, slum dwellers, artisans or school dropouts, and has a repository of more than 100,000 grassroots innovations and traditional knowledge practices including those from Rao, Vasoya and Udgave.

Grassroots innovations cannot work in isolation; they need funding, access to markets and development infrastructure. Organisations such as TeNet, RBTI, Villgro, NIF and CSIR are few and far between. They often work in isolation. But these organisations play a large role in the change of mindsets that Mashelkar talks about, nurturing innovators at the grassroots by encouraging an all-pervasive attitudinal change towards life and work. Many intellectuals in India have characterised the shifts required as one from a culture of drift to a culture of dynamism, from a culture of idle prattle to a culture of thought and work, from diffidence to confidence, from despair to hope. In part these organisations have revived creativity and the innovative spirit and are making a difference in their pockets of influence. What is missing is a coordinated effort of national significance amongst the players.

Navi Radjou is currently the Executive Director at the Centre for India and Global Business at the University of Cambridge. Navi and I have known each other since his tenure at Forrester Research and mine at SETLabs and we share the common passions of innovation and India. After a field trip to India in early 2009, what struck Navi most, as he writes in his Harvard Business blog,5 is that most Indian innovators – both large and small – are now single-mindedly targeting the rural market, which accounts for 70 per cent of India’s population. Navi believes that the only way India can sustain its long-term economic growth is by unleashing and harnessing the creativity of its grassroots entrepreneurs, especially in rural areas.

One of the private sector companies that capitalised on this trend very early is ITC, an Indian company with a turnover of over US $5 billion that has a significant presence in agricultural business, packaged foods and confectionery. These parts of the company’s business depend heavily on rural produce for its domestic agriculture and exports businesses. Bringing in sustainable supply chain innovation that benefits farmers and ITC was a necessity. ITC’s e-choupal is a well-documented and popular case study6 of this worldwide.

S. Sivakumar is the Chief Executive, Agri Businesses at ITC Limited. For Sivakumar’s organisation the challenge was to create a win–win situation for farmers and the bulk buyers in the organised sector, bypassing the mandis and middlemen. In the mandi auction model, farmers had to wait days to sell their produce and get paid in return. Unfair practices in weighing and determining quality of produce were prevalent. Those farmers who had smaller farms of about 1.5 hectares on average had extremely low bargaining power. And in most cases a farmer buys raw materials at retail price and is forced to sell his produce at wholesale prices. Their plight was further compounded by geographical dispersion, limited access to the right information, and poor physical, social and institutional infrastructure.

Launched in June 2000, ‘e-Choupal’ has already become the largest initiative among all Internet-based interventions in rural India. ‘e-Choupal’ services today reach out to over 4 million farmers growing a range of agricultural produce – soybean, coffee, wheat, rice, pulses and shrimp – in over 40,000 villages through 6500 kiosks across ten states.

The ITC model with its IT-enabled kiosk system and inbuilt payment gateway allowed farmers to use local village-level e-Choupals managed by villagers themselves. Farmers have more confidence when the system is operated by one of their own. They agree on the price, sell and receive expert advice on agricultural challenges such as pest control before transporting their produce to the ITC warehouses. Sivakumar tells me that e-Choupal unlocked the potential of Indian farmers who had been trapped in a vicious cycle of low-risk taking, low investment, low productivity, weak market orientation, low value addition and low margins. This made farmers and the Indian agribusiness sector globally uncompetitive, despite rich and abundant natural resources.

The ITC model with its IT-enabled kiosk system and inbuilt payment gateway allowed farmers to use local village-level e-Choupals managed by villagers themselves. Farmers have more confidence when the system is operated by one of their own. They agree on the price, sell and receive expert advice on agricultural challenges such as pest control before transporting their produce to the ITC warehouses. Sivakumar tells me that e-Choupal unlocked the potential of Indian farmers who had been trapped in a vicious cycle of low-risk taking, low investment, low productivity, weak market orientation, low value addition and low margins. This made farmers and the Indian agribusiness sector globally uncompetitive, despite rich and abundant natural resources.

Market-led business models that engage farmers at the points of their disadvantages can enhance the competitiveness of Indian agriculture and trigger a virtuous cycle of higher productivity, higher incomes, enlarged capacity for farmer risk management, larger investments, and higher quality and productivity. For instance, India will need about 400 million tonnes of grain by 2047, or more than double the current production, on more or less the same arable area. Productivity must therefore double, which requires huge investments in irrigation and on improved land and water management. The scale that is required but currently missing is a mechanism to cross-pollinate and scale up these brilliant ideas. India’s 130 million farmers constitute one-third of its work force, but live scattered across more than 650,000 villages. This is a classical example of where innovations can support the enablement of rural populations in contributing to rural and national GDP.

An example in the healthcare sector is the Aravind Eye Care system7 in Tamil Nadu. Aravind is the world’s most productive and largest eye care hospital. When a friend, now an ophthalmologist in the UK, trained for his FRCS he chose Aravind. It undertakes some 2.7 million consultations a year and performs a staggering 280,000 operations a year, meeting 8 per cent of the country’s needs and 45 per cent of the state’s need. This alone is a significant contribution to social welfare given that over 65 per cent of the operations are conducted free of charge. The economic impact of blindness, Dr S. Aravind, Director & Administrator at Aravind, tells me, is about $3 billion a year, due to loss of employment, and need for home care and constant adult support. India alone has 12 million blind, most of these cases being preventable or reversible.

Aravind is able to perform such a huge number of mostly cataract surgeries because of its innovative approach to build scale. Cataracts account for nearly 50 per cent of cases of blindness in the developing world. Aravind has an assembly line operation to reduce costs and time and increase efficiencies. It has highly standardised cataract surgical techniques using proven procedures and tools. This has helped it to manage its fixed costs, which are typically 80 per cent of the eyecare costs. The assembly line operations have enhanced Aravind’s return on assets. Aravind also uses VSAT (a satellite communication technology) and WiFi technologies for upstream screening and diagnostics to determine the type of patient care and those marked for surgery are brought to the five hospitals Aravind operates. The same technologies are used for postoperative care, reducing the costs incurred by patients to travel.

Over and above this, Aravind has begun manufacturing its own IOLs (intraocular lenses). The need arose from the prohibitive prices of IOLs offered by multinationals. From typical costs of around $100, the best discounted deals were available at $35, still more than $25 what patients could afford. Aravind now produces more than 1 million of these lenses each year and sells the surplus to facilities in India and abroad; it has 7 per cent of the global market in IOLs today.

Aravind has a corporate social responsibility agenda that is driving its vision for the poor but Aravind’s is also an example of a company that addresses what C. K. Prahlad calls the fortune at the bottom of the pyramid. Aravind is a classic example of how cutting-edge research can be brought to solve rural problems sustainably.

The national innovation system imperative

Bringing innovative ideas to market involves complex interlinkages among industry, academia and government within multiple overlapping ‘innovation ecosystems’. This ecosystems approach emphasises the importance of creating and improving institutions to interweave the different parts of a nation’s innovation system. What is needed is a national innovation system (NIS) that operates like a national grid in which innovation change agents can be plugged in, and where common issues can be abstracted and dealt with separately. By harnessing all the nodes of positive influences for scale, the NIS functions like a dynamic web of public–private partnerships that broker transactions between grassroots innovators, entrepreneurs and large corporations. Such a national grid will connect banks, venture capitalists, markets, technologists, public R&D entities, universities, NGOs, national industries and global networks. Their primary role would be to convert native knowledge into revenue and viable wealth creation opportunities at different levels. The NIS may have an apex body that serves as a policy-orientated intellectual property think-tank.

The impact of an NIS will be phenomenal. First, the NIS will not only level the path for rural ideas to markets but offer a policy perspective to increase collaboration, and propose levers like matching grants, tax credits and cognitive support for pro-poor early stage technology development that will be available to all participants in the NIS and nodal networks such as NIF, Villgro and TeNet. Secondly, an NIS will also capture the nation’s imagination and raise the profile of challenges of gargantuan impact such as clean drinking water throughout the country.

The NIS will also address the fragmentation of India’s current innovation system; encourage collaboration and facilitate streamlining of the system’s constituent programmes, using public–private partnerships wherever appropriate; and monitor the achievement of realistic targets, with periodic international benchmarking, as India’s innovation potential is unleashed. It will also help existing pro-poor initiatives to scale up. Thirdly, the innovation system will also provide digital integration of disparate innovation initiatives and will reduce the reinvention of the wheel that occurs in many disjointed entities. For large organisations, it will then become easier to come forward to recognise and reward rural innovations and innovators and be active contributors themselves. The NIS will become a coordinated effort of national significance.

It may also be possible to focus on ideas that have applications in rural contexts and ideas that are part of the industrialised world. For example, extremely inexpensive agricultural innovations, building low-cost companies or providing investments in a broadly distributable processed food industry, may be given priority in the initial phase. The NIS will provide the ecosystem for innovation that can reduce the investment risks of companies that fund efforts in these areas. The NIS will help manage a national portfolio of innovations where state and central funds can be channelled. The operation of the NIS is discussed in detail in the final chapter.

1.Lakshman, N. (2008) Indian textiles: weaker rupee is no help. Business Week, 5 November.

2.Aruna Roy (born 26 May 1946) is an Indian political and social activist. She served as a civil servant in the Indian Administrative Service from 1968 to 1974, before resigning to become a social activist and working to empower villagers in Rajasthan.

3.In his book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits, University of Michigan Professor C. K. Prahalad proposed the idea that if the demographic map of the world’s population were to be looked at as a pyramid, the bottom represented the volumes of masses who cannot afford the goods of the middle classes but has strength in numbers. If companies produced goods and services at prices that are affordable for poorer populations of the world, there is a fortune to be made.

5.Radjou, N. (2009) India’s Rural Innovations: Can They Scale?. Harvard Business Review, http://blogs.harvardbusiness.org/radjou/2009/04/indias-rural- innovations.html

6.Upton, D.M. & Fuller, V.A. (2004) ITC eChoupal Initiative. Harvard Business School.