The tipping point eras

Imagine not being able to use a radio that you had just bought. Imagine not being able to take foreign currency out of the country when you travelled overseas. Imagine having to pay up to 300 per cent in customs duty on a tape recorder or a bottle of perfume when you entered the country. Such was India in the 1970s and 1980s – a nation that stood in the way of its own progress.

Most Indians have forgotten the era when they needed clearance from the Indian central bank for traveller’s cheques. Or the time they were delayed at customs over duties on perfumes, imported wine or electronics. Haggling over imported items such as a camera, jewellery, a digital wristwatch or a two-in-one radio in airports was common. An occasional tip or bribe for the customs officer still shamefully exists in some locations but such sights have virtually disappeared in the last 20 years, thanks to opening of India’s domestic market to imports. These are perceptible, tangible and quantifiable changes, and the underlying economics and pace at which they were dismantled has been breathtaking.

India gained independence twice, once from Britain in 1947 and the next from its own trenches 44 years later in 1991. But it so far has taken over 19 years to establish a foundation for economic growth. India is finally on its way to prosperity. In the next 30 plus years towards its independence centennial in 2047, it will be a climb like never before. It will be sustained, inclusive and national.

A three-dimensional framework to study India

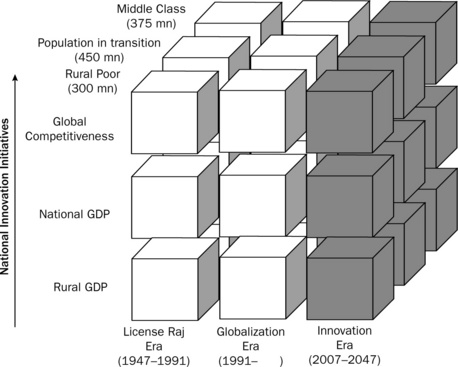

Any study of India needs to be undertaken from at least three perspectives: (1) its 100-year history, with tipping points bounding tipping-point eras; (2) its three-tiered socio-economic structure defined by the 375 million (and rising) middle class, the 300 million people in extreme subsistence (under a dollar a day) and the approximately 450 million middle layer in transition; and (3) the differing demands of global competitiveness, national growth and rural GDP needs. These perspectives can be directly linked to the need for innovation through cutting-edge research, national innovation and grassroots innovation. What results is a three-dimensional framework that resembles a Rubik’s cube (Figure 2.1). Each of the 27 smaller cuboids that make up the Rubik’s cube tells a unique story that make up the national aggregate in a defined point in time. I will revisit this framework throughout the book.

Why a 100-year perspective?

A lot can happen in 100 years. The modern values of social justice, racial equality, voting rights for women and protection of human rights developed over the last 100 years. Whenever I present the Indian story I am soon made aware of the ‘elephants in the room’ – poverty, disease, poor infrastructure and poor governance. My audience usually establishes this through a statistical report, anecdotal reference or personal experience. This is precisely the reason the data need to be viewed in context. First, modern India is not being judged fairly on the time scales used for comparison. The G7 countries have had at least 100 years of independent and sovereign history to mend and build themselves. And all G7 countries have had their economic troughs, be it the great depression of the 1930s or the two world wars that sandwiched it. Consider England in 1854, the year of the Broad Street cholera outbreak in London. Over-running cesspool water was dumped into the River Thames and water from the Thames was pumped for domestic use. Six hundred and sixteen people were reported to have been killed in the epidemic. More people were killed by this outbreak in London in 1854 than from the pneumonic plague that hit Surat in 1994 in India. Surat had 52 deaths and a large internal migration of about 300,000 residents who fled fearing quarantine. London and Surat had similar conditions 139 years apart but the difference was that the Surat outbreak was preventable and India had access to the resources to prevent it. Surat’s challenges are in a way unique to most populous countries today, where population size has a direct impact on the economics and scale of any developmental initiative. Consequently, problems receive the attention they deserve only when they are blown out of proportion. Wherever problems have hurt India, its population has magnified the impact, and ironically wherever India has grown, its population was the reason for it. Like London, Surat today has achieved a turnaround and has been voted one of the cleanest cities in the country, ahead of Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore.

Change needs time. Electricity was discovered only in 1873. The US achieved 100 per cent electrification only in the 1950s – over 75 years later. Infant mortality in America in the 1900s was equal to India’s infant mortality rate 20 years ago. In the last 100 years, infant mortality in the US has fallen by 95 per cent. At the end of the nineteenth century, life expectancy in America was 47 years. America was not a wealthy nation 70 years ago. At the beginning of the last century, agriculture was not propelled by John Deere and Caterpillar tractors, but by horses and mules. In the 1920s, deadly diseases were still being carried via drinking water and milk in the US.

Without ignoring India’s pitfalls, it must be pointed out that the gaps between India and the developed world are not uniform. The lag between India and the G7 nations in the quality of telecommunications is extremely narrow. In fact, India’s rural telecommunications infrastructure, where it exists, is more advanced than in similar rural areas of many developed nations. Australia, where I now live, is only now beginning to create a National Broadband network.1 India’s IT industry is on par or better than the G7 nations in terms of both adoption and driving migration towards newer, less expensive technologies. India has better legal and financial systems, a greater number of professional managers and better entrepreneurial talent than China. India is also a vibrant democracy. It has rule of law and enviable demographics.

Unlike many countries in the developing world, India has the tenacity and the mettle to manage what would otherwise have had disastrous consequences. The Satyam Computer Fraud, for example – the largest in India’s history – unfolded in December 2008. Within 13 weeks the government and Satyam’s new board facilitated change of ownership to a strategic investor, Tech Mahindra, demonstrating the strong governance, and financial and legal frameworks that exist in the country to protect investor confidence.

Modern India should be seen as the result of three eras. The years 1947, 1991, 2007 and 2047 are India’s tipping point years. It took 44 years, after independence in 1947, which I define as the licence raj (a term adopted from popular literature), for India to liberate itself from the shackles of economic depravity brought in by the socialistic thinking of its founding fathers. By 2011, India would have completed only the 20th anniversary of its birth into a free enterprise economy. At the time of writing, India has barely left its teen years, so to speak, as a modern economy. I call this period and beyond the globalisation era. Much of India’s innovation-led growth is expected to come in the next 40 years of what I call the innovation era towards the centennial year 2047, beginning at the onset of the eleventh five-year plan in 2007. Most of this chapter focuses on the Licence Raj era, Chapters 3–5 cover the globalisation era, and Chapters 6–9 focus on the innovation era in greater detail.

The socio-economic perspective

We can also look at India from the vantage point of its socio-economic structures, distribution of wealth and quality of life within these structures. It is clear that wealth is not evenly distributed in the country. There are hot spots of wealth in and around the mega and metropolitan cities – Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore and Hyderabad, and smaller cities such as Pune and Cochin – and rural wealth distribution is even more of a contrast. For example, one can find parity in rural wealth and quality of life in the states of Kerala, Punjab and Haryana as compared with Uttar Pradesh, Bihar or Jharkhand. Therefore, the drivers, challenges, opportunities and threats to socio-economic prosperity vary widely within the Indian peninsula to the point that India could be characterised as having nearly all the complexities of Africa plus, in many areas, the affluence of the United States, attributable to its rising 375 million middle class.

The foremost needs of the Indian population, from villages, towns and urban slums, include health care, education, skills, training, infrastructure, and employment to support rural wealth creation and growth of GDP, to aid reverse migration to cities and sustenance of India’s rural economies. On the other hand, the 375 million middle class need to be supported and funded to create opportunities for their aspirations, which in turn can support national and global competitiveness. Funding for R&D, innovation, talent and human resource development, energy, the environment, and infrastructure for growth are critical but the requirements across the socio-economic structures vary widely. India therefore requires a portfolio approach over the next 40 years – one that is defined by an understanding of specific needs and balanced between the need to exponentially increase rural GDP and the need to sustain national GDP growth; this is India’s biggest challenge. Simply put, it is akin to managing the complexities of the African continent and sustaining the aspirations of a country like the United States.

Every decision made will be influenced by these competing forces. The dilemma will be between deciding whether to create more rural innovation networks, rural entrepreneurship programmes for basic wealth creation or catering to the bottom of the pyramid, or whether to build more high-class R&D centres and national R&D programmes – space research, biotechnology, smart materials, new process industries (e.g. food processing) or new products like the Nano car.

I believe that India is at an inflexion point where some of its mature sectors and all parts of the private and public sector of the economy in manufacturing and service sectors such as IT, automotive and pharmaceuticals need to unlock their innovation prowess. Other areas, by contrast, need more of an investment portfolio approach to first drive them to levels of maturity and sustainability at the local level before they can scale up to the demands of the global market.

The context of innovation

The context behind innovation is as important as its relevance. Protectionism during the Licence Raj, while hindering private enterprise, fuelled indigenous innovation for the sake of self-sufficiency whether it was in the aviation industry, energy sector or defence. Having said that, I believe the term Innovation needs to be seen as a broad one in the context of India. It should not be restricted to product or technology innovation. There is ample room for incremental and disruptive innovation. In many cases, process and service innovation is produce-relevant rather than product or technological innovation. Social innovation is even more critical.

At different levels of the socio-economic structure innovation needs differ: for example, the innovation demands of the emergent India, namely those of the 450 million people transitioning from below poverty to the middle class. Half of this population have a mobile phone but may not yet have a toilet. Innovation at this level needs to focus on generation of employment for the skilled manufacturing, service or process industries. A call centre that serves the larger cities but operates from a much smaller town or city is a classic example of the type of innovation required at this level. Food processing industries are another example; food produced by the larger agriculture communities in rural India is processed and packaged for national consumption or even export, thus helping the emergent Indian population. Today much of India’s agricultural produce is wasted for the lack of a plan to extend its shelf life.

Then there is the third layer of innovation (grassroots innovation) required for the poor surviving on less than a dollar a day who are unskilled, often heavily dependent on traditional agriculture, and dependent on climatic conditions, unscrupulous landlords and government aid. Innovation for this group needs to produce specific outcomes that will generate employment and provide social security that will enable the next generation to go to school and have access to good health care. An example of such innovation is the government’s employment guarantee scheme, NREGA,2 which emerged from a collaboration between Jean Dreze, a visiting Professor at the Department of Economics, Allahabad University, and the Government of India. Other examples are improved disease-resistant seeds with low water needs for farmers and improved infrastructure, including broadband Internet access.

India also needs a factor-driven (where the economy relies heavily on natural resources) growth strategy that emphasises efficient production for parts of its economy that are well endowed with primary resources. It also needs improved use of technology for greater productivity. As the technological gap with areas of growth shrinks, the focus must shift towards the development of innovation capabilities to create competitive advantages.

Local transfer of technology and knowledge needs to be encouraged. Indian technology companies who pioneered the outsourcing industry have now matured and have grown by the adoption of best practice in quality or service management. Their rapid hiring and adoption of proven business culture and practices made them flagships for India’s transformation from a single-sourced inward-looking nation to a global commercial player. The proliferation of business practices into other sectors like banking, capital markets, finance and retail have been quicker in India than in most countries. These practices and know-how must reach the emergent Indian population and rural India via a framework of collaborators.

1947: Licence Raj thinking

Between 1947 and 1991, India’s protectionist and self-reliance policies had crippled free enterprise, protected its under-performing public sector and shielded its markets from the forces of the open market. That protectionism had impacted deeply on the mindsets of its working class, reflecting the way they thought, invested, focused and lived. Industrial production was not governed by natural demand for products and services. Demand merely reflected a lack of choice. Until the 1990s, wealth creation was seen as a capitalistic idea of the West. Profit motives were seen as greed and efficiency as anti-socialistic. An improvement in lifestyle beyond the lowest ranks in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs was seen as hedonistic.

Even today, some business and political leaders who are witnessing India’s emergence as a free market economy from within a Fabian3 mindset are unable to free themselves from the Licence Raj mentality. The Licence Raj marked the years following independence in 1947 to dependence on a government licensing system for everything from setting up a factory to importing a toothbrush. It discouraged industry from taking an active interest in adoption of technology for quality, or productivity. Competition was systemically discouraged. The system punished those who produced more than a licensed quantity: if a business licensed to produce 100,000 bars of soap produced 110,000 bars of soap, it was penalised. In 1991 things changed. It was as if the flood gates of economic freedom were thrown open for the first time in India’s post-independence history.

An Indian statesman once put it movingly, ‘A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.’ These words were spoken by the country’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, just after midnight on 15 August 1947. What Nehru was referring to, of course, was the birth of India as an independent state.

From his perspective, Nehru may not have fully endorsed free market capitalism, but he did understand political freedom. Nehru’s words were not about economic freedom, but since 1991, India has achieved this and has an independent free market economy, one that is open, energetic, colourful, vibrant and, above all, ready for change. India is tearing itself from its past. The process has, however, been slow, akin to a giant oil tanker changing course. To the outside world India still is a chaotic democracy as before but with one fundamental shift – it is finally empowering its people economically. In this respect India now looks noticeably similar to the world’s most competitive nation, the United States. In both, society has triumphed over the state, Fareed Zakaria, Newsweek’s International Editor points out.

Most of the challenges India eventually faced resulted from the planning it did shortly after independence. Leaders of independent India chose socialist economic planning. Nehru’s model was not as rigid as that adopted a few years later by Mao in China but it drew heavily on the Fabian mixed economy approach advocated by Harold Laski.4 Laski was Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics from 1926 until his death in 1950 and a leading figure in both the British Labour Party and the Fabian Society.5 Laski advocated a central role for the state in industrial ownership, notably energy transport and basic industries but also in economic planning. As a result, India adopted five-year economic plans that began in 1951 (the eleventh five-year plan is at work at the time of writing).

But it was India’s long-standing friendship with the former Soviet Union that cemented the thinking of its leaders in fostering a socialistic and welfare-orientated approach and opposing everything the West undertook in the name of development. Infosys’ pioneer, N. R. Narayana Murthy, would often tell his team that if we try and distribute wealth without creating wealth we are distributing poverty. This is exactly what India was doing for much of its independent history.

As a result of the socialistic approach of India’s leaders, the country failed to match the progress of countries like Japan, Korea, Germany and Singapore. India did not have to bear the brunt of the devastation suffered by Germany. Nor did it have the land limitations of Singapore, or suffer the catastrophies that Japan did at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or suffer the ravaging effect of the Korean war. It just didn’t do enough to progress itself even when it had the resources. Rather, it took on a quasi Fabian philosophy6 that was not overtly Marxian but socialistic enough to be regarded as a democracy. It refuted capitalism, derided wealth creation and actively discouraged entrepreneurs.

One might argue that such judgments are harsh on a nation whose immediate concerns were to prevent famines and the deaths from starvation that were commonplace under British rule. There were at least 10 severe famines under the British crown that the government did nothing about. The world’s worst recorded food disaster happened in 1943. Known as the Bengal Famine, an estimated three million people died of hunger that year alone in eastern India (including today’s Bangladesh). The initial theory put forward to explain the catastrophe was an acute shortfall in food production in the area. However, economist Amartya Sen7 established that while food shortage was a contributor to the problem, a more potent factor was the result of hysteria related to World War II which made food supply a low priority for British rulers. The hysteria was further exploited by Indian traders who hoarded food in order to sell at higher prices. It was therefore natural that food security was a paramount item on free India’s agenda. When the British left India in 1947, India continued to be haunted by memories of the Bengal Famine. The years following independence were telling. It led, on the one hand, to the Green Revolution in India and, on the other, to legislative measures to ensure that businessmen would never again be able to hoard food for profit.

India ensured food security by continued expansion of farming areas, double-cropping in existing farmlands and using seeds with improved genetics. Over the following three decades it amassed surpluses through the Green Revolution, and this continued into the 1970s. With the exception of the seeds sown for prestigious institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology, a space programme and a few laboratories between 1950 and 1970, independent India failed miserably in laying the foundations for growth in its economy when it had the opportunity. Unlike many of the African nations that gained their independence from Britain only to deteriorate in the years following, India did not inherit a well-managed country: life expectancy was around 28 years, infant mortality (below 1 year of age) stood at around 114 deaths for every 1000 live births, adult literacy was 14 per cent, and per-capita income was as low as $411. After securing food security, India started a relentless pursuit of science and technology for self-reliance but elsewhere it left a gaping hole.

Independence offered a window of opportunity for India to emerge as a superpower, but this was missed by allying itself with the USSR, a ruthless near dictatorial regime under Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev that was extremely suspicious of Britain and its empire and the collective West. Khrushchev broadened Moscow’s policy to establish ties with India and other key neutral states. India’s resentment of the British legacy made it a willing partner to Khrushchev’s advances, further alienating India from the only economic models that have withstood the test of time: prudent capitalism. India also systemically resisted anything that was ‘foreign’ through its policies. India’s new leaders took the British apathy for India’s progress to the other extreme by rejecting every idea and proposition from the West, even while Britain and its allies were reforming themselves from colonial thinking. Culturally Indians began to replace ingenuity with indigenous prowess yet they saw value in things foreign for the sheer merit they had in enhancing the quality of life. The cultural impact was telling. Some educated individuals, the country’s best, left India for jobs overseas, leading to a brain drain. It was ironic that much of the investment made in nurturing a scientific talent was being lost. Those who remained in India battled against government policies. And when they couldn’t beat them, they joined them, taking up secure government jobs.

Fareed Zakaria writes that in the 1950s and 1960s, India tried to modernise by creating a ‘mixed’ economic model, somewhere between capitalism and communism.8 This left a shackled and over-regulated private sector, and a massively inefficient and corrupt public sector.

India’s decline begins

In 1960 India had a higher per-capita GDP than China; today it is less than half that of China. In 1960 it had the same per-capita GDP as South Korea; today South Korea’s per-capita GDP is 13 times higher. The United Nations Human Development Index gauges countries by income, health, literacy and similar measures. On this basis, India ranks 134 out of 182, behind Egypt, Colombia, Lebanon, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. Female literacy in India is a shockingly low 54 per cent. Despite mountains of rhetoric about helping the poor, by any reasonable comparison, India’s government has done too little for them until recently. There are elements of democracy that have hurt certainly in a country with rampant poverty, feudalism, caste politics and illiteracy, but they are clearly not a problem with democracy per se. Poor policies fail whether pursued by dictators or democrats. Liberalisation ushered in hope as if a thousand flowers had bloomed in springtime. Despite much progress, there is much still to be done.

Vasant Sathe was minister for Steel, Mines & Coal in 1985. Shashi Tharoor, in his book India: From Midnight to the Millenium,9 quotes Sathe’s archetypal and appalling examples of public sector apathy. In 1986, the Steel Authority of India paid 247,000 people to produce some 6 million tonnes of finished steel, whereas 10,000 South Korean workers employed by the Pohan Steel company produced 14 million tonnes that same year. Home-grown products that emerged from this labour-intensive process were uneconomical and expensive. India’s finished steel cost $650 per tonne so it found few buyers abroad as world prices were between $500 and $550 per tonne.

Ironically, India’s raw material – iron ore – was cheap enough to be imported by foreign steel manufacturers who used it to manufacture their own steel cheaper than India could. Sathe pointed out that if India had been able to make steel efficiently to world standards and at the world price, it would be earning significant profits from exporting finished steel whereas it was now exporting iron ore and making just 75 rupees a tonne. In colonial times, India was a source of raw material for countries that did their own manufacturing, and it was still doing so.

What this lackadaisical approach to industrial production delivered was a mixed bag – products and services for national consumption of substandard quality. Indians rarely sought or demanded quality in the goods and services offered to them. Indians had few opportunities to benchmark themselves regarding what they were producing and consuming with what were available from other countries. This meant that quality, competitiveness, value for money and even safety were often sacrificed. At the same time, for many enterprising Indians foreign goods were alluring – so much so that demand for them made smuggling a profitable blackmarket business. In fact, Suketu Mehta points out in his book Maximum City: Mumbai Lost and Found that the Mumbai underworld thrived on its prowess in smuggling gold, electronics and other contraband from the Persian Gulf to India.10 Mehta notes that when the economy opened up, smuggling of goods died down but the same routes were now being used to smuggle arms for terrorist operations.

I worked for a brief while as an apprentice electrical maintenance engineer at the prestigious state-run Fertilizer and Chemicals Travancore (FACT Ltd), a multi-billion-rupee fertiliser plant that operates from Kerala. The brief given to us was to ensure that furnaces were running at all costs. Our jobs were not seen as impacting the quality and value of the ammonium phosphate and ammonium sulphate that we produced, but on ensuring that any breakdown was never the fault of the electrical department. Preventive maintenance was rarely done. So we ran the motors until they broke. When they did, the blame was quickly passed on to the spare parts and procurement department for not stocking spares. We made sure that breakdowns were never a maintenance issue even though each breakdown amounted to millions of rupees in lost production. What I distinctly remember is that even though most maintenance staff reported to work at 8:00 in the morning because we had to fill in time sheets, no one began to work until morning tea was served at 9:00 am – there was no urgency. Seats were full half an hour prior to subsidised lunch at midday. Several of the state-owned companies, like FACT, were kept running merely to provide jobs. Closing them resulted in job losses, poverty and political fallout.

Tharoor notes that between 1992 and 1993, of the 237 public-sector companies in existence, 104 made losses, amounting to some 40 billion rupees of Indian taxpayers’ money. Most of the remaining 133 companies made only marginal profits. The figures had undoubtedly worsened; according to a report in Time magazine in March 1996, the country’s public sector electric utilities alone lost $2.2 bn in the preceding 12 months or 70 billion rupees a year. Other public-sector industries that experienced losses were not far behind. In 1994, one British journalist, Stefan Wagstyl of the Financial Times, reported in disbelief that the government-owned Hindustan fertiliser factory in Haldia, West Bengal, employed 1550 people but had produced no fertiliser since it was set up at a cost of $1.2 billion (and after 7 years of construction) in 1986.

India had its worst growth spell between 1950 and 1980, when annual growth was below 5 per cent, prompting Indian economist Raj Krishna to call this the Hindu rate of growth. (Ironically, today developed economies grow at the Hindu rate.) Growth stagnated at around 3.5 per cent from the 1950s to 1980s, while per-capita income growth averaged an extremely low 1.3 per cent a year. At the same time, Pakistan grew by 8 per cent, Indonesia by 9 per cent, Thailand by 9 per cent, South Korea by 10 per cent and Taiwan by 12 per cent.

In the late 1980s, the government led by Rajiv Gandhi eased restrictions on capacity expansion for incumbents, removed price controls and reduced corporate taxes. Although this increased the rate of growth, it also led to high fiscal deficits and a worsening current account. The collapse of the Soviet Union, which was India’s major trading partner, and the first Gulf War, which caused a spike in oil prices, caused a major balance-of-payments crisis for India, which found itself facing the prospect of defaulting on its loans. India asked for a $1.8 bn bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in return demanded reform. In fact in 1991 a large part of the country’s gold reserves had to be flown to London as collateral in exchange for the IMF loan. Without the loan, India would have defaulted on its international debt and the economy would for all practical purposes have collapsed. The country’s foreign exchange reserves stood at just under $1 bn and would have covered two weeks of oil imports; the Gulf War had raised oil prices and Indian workers in the Gulf who were sending their remittances home were fleeing.11

When P. V. Narasimha Rao, the Indian Prime Minister who oversaw the dismantling of the Licence Raj, stated that ‘full freedom to dream the way you like came in 1991, not 1947’, those words were born out of desperation, realism and pragmatism. They came at a time when the Indian economy had bottomed out. The end of the Cold War coincided with a balance of payments crisis and the liberalisation of the Indian economy, which opened India to globalisation. The revolution in information and communications technologies offered India the opportunity to transcend the limitations imposed by colonialism and its legacy of hard frontiers of the 20th century. Educated sections of Indian society found themselves in a good position to take advantage of globalisation. But it did better than that. Over the past 20 years, India has been the second fastest growing country in the world – after China – averaging above 6 per cent annual growth. Having grown at almost 10 per cent since 1980, China’s rise is already here and palpable. India’s is a future in the making and one that is coming into sharp focus.

What the 60 years achieved

In 1947, India’s national priorities were very different. ‘The utterance’ Nehru spoke about was a groaning for self-reliance. Approximately 3 million people had died of one of the worst famines recorded in human history four years prior to Independence. Food security was of prime importance, so much so that with scrupulous planning and support from friendly nations, India managed to become a food-exporting country in 20 years and became a classic example of the Green Revolution of the 1960s. Over the last 60 years, economic growth has gradually accelerated, with per-capita income rising at 1.5 per cent annually until 1975, at 3 per cent until 1993, and at over 7 per cent in the last three years. Simultaneously, India embarked on a vision of self-reliance that led to the laying down of a solid foundation for science and technology, setting up laboratories, research institutions, institutions of higher learning, a space programme and an atomic research programme. These initiatives helped India to become the third largest scientific and technical pool, producing some 7000 PhDs every year and generating enough talent for 800 plus R&D centres from 350 universities and institutions today. It created a higher education system that annually produces 3 million graduates, 700,000 post-graduates and 1500 PhDs in the scientific stream, setting up a solid foundation for innovation. In the same 44 years, its model for creating growth engines for the economy, which was heavily reliant on the public sector, failed miserably. Although India produced so many talented graduate engineers, it failed to provide them with employment opportunities and many of them left the country.

Although theoretically capitalism had the edge, socialistic policies were introduced in India at a time when both capitalism and communism were unproven in the rebuilding of the global economy after World War II. With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that capitalism and free market economics led the G7 resurgence in spite of the oil glut of the 1980s, the economic downturn of 2000 and the global economic meltdown of 2007. Today even the most sensible defenders of capitalism, by and large, agree that its tendency to form cartels, shuffle off the costs of pollution and collapse under the weight of its own financial inventiveness needs to be constrained by laws designed to channel its energy to the general good. This does not absolve India for having chosen the wrong models for growth.

The disconnects

People visiting India struggle with one fundamental conundrum; the ideological struggle to make the connection between the visible and lacking physical infrastructure and the invisible mental infrastructure of the country. Most people who have worked with India soon realise that ‘what you see is not what you get’. I was recently at dinner with a colleague in a restaurant in downtown Sydney. A group of Australian businessmen broke into our conversation. They had done business in India and were quick to provide instances of how they had made money in various ventures. The 2010 Commonwealth Games came up in the conversation. I had read that international organisers of the Games were already concerned about India’s ability to get the infrastructure ready on time. One of the businessmen said, ‘they don’t do it the way we do it, but they will get it done. Trust me.’ Experience overwhelms reason in India.

Very few people get it. Former chairman of the General Electric Company, Jack Welch is one of the few who understood India well. Jack famously said, ‘India is a developing country with a developed intellectual capability’. In his book Straight from the Gut,12 Welch narrates a story from his first visit to India. In the early 1990s on an initial exploratory trip to India, the GE team was picked up in the middle of the night from Delhi airport in a caravan of five Indian Ambassador cars. He recalls hearing a thud in one of the cars to the rear and it was later found that the hood of the lead car had flown off smashing the windshield of the car behind. The caravan of GE executives pulled over to the side of the road, and everyone was shaking their heads and thinking, ‘Is this the place we’re going to get software from?’. The rest as they say is history. GE became one of the most formidable advocates of the India story.

The achievements of the last 60 years or so have been scattered, isolated and incoherent. For example, the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) report on India’s competitiveness review for 2009 shows that India has moved up in global competitiveness by just one notch from 50 in 2008 to 49 in 2009.13 This is despite the initiatives India has undertaken so far with respect to what the WEF defines as factor-driven economies (effective use of natural resources). On the basis of the quality and quantity of institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic stability, and health and primary education, India ranks 79 out of 114 countries on this basis. India has a desperate need to improve on these scores.

Table 2.1

There are distinct stages of development that characterize national growth

| Stage of development | GDP per capita (US$) | Example countries |

| Stage 1: Factor driven | < 2000 | India, Pakistan, Philippines, Vietnam |

| Transition from Stage 1 to 2 | 2000–3000 | Indonesia |

| Stage 2: Efficiency driven | 3000–9000 | Brazil, China, Malaysia |

| Transition from Stage 2 to 3 | 9000–17,000 | Russian Federation |

| Stage 3: Innovation driven | > 17,000 | Republic of Korea, United States |

Source: World Economic Forum 2009a.

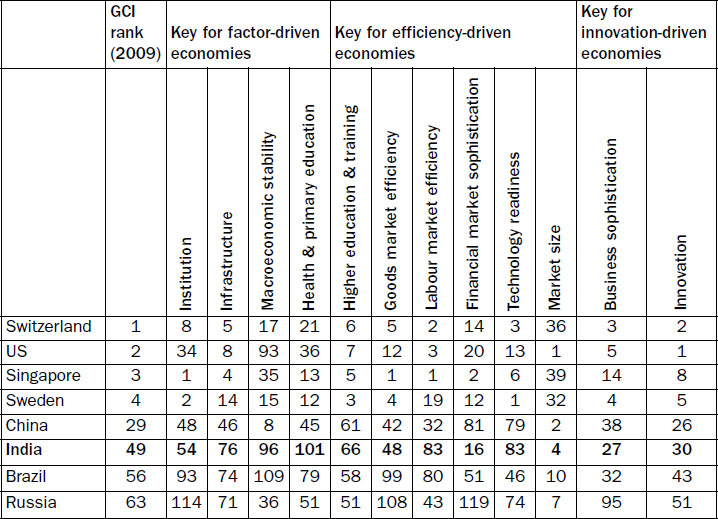

These scores have been by far the most difficult and challenging to improve and the conditions have often paralleled those of Pakistan, the Philippines and Vietnam. On the metrics for the WEF’s efficiency-driven economies, India shares 35th position with Brazil, China and Malaysia in terms of higher education, market efficiencies and technology readiness. India ranks at 27th position, better than China, Brazil and Indonesia, among the 114 countries studied for business sophistication and innovation (Table 2.2). These scores are not particularly bad but the challenge will be that unless the factor-driven and efficiency-driven economic measures are improved, business sophistication and innovation will not be sustainable and will crumble under the weight of dragging the nation forward.

Table 2.2

India is ahead of other BRIC countries in terms of Business sophistication and ahead of the US in terms of Financial market sophistication

Source: Adapted from the Global Competitiveness Report 2009–2010, World Economic Forum, pp. 16–20.

Innovation and R&D is one area where India is consistently ahead of China and may prove to be the country’s differentiator if managed well. To the question ‘how would you assess the quality of scientific research institutions in your country’ in an executive opinion survey conducted by the WEF, Switzerland, the USA and Israel were ranked as the top three countries with a score of above 6 of a maximum of 7. India was ranked 25th with a score of 4.9 and China at 35 with a score of 4.4.

2007: The beginning of the innovation era

Despite the global financial crisis, in many ways the year 2007, the beginning of the 11th five-year plan, marks the onset of the innovation era. First, the same leadership team that disbanded the Licence Raj and deregulated the economy returned to power, but now with a majority in parliament after the elections of 2009. In 2008, a new National Innovation Act (NIA) was drafted. The NIA is primarily aimed at boosting investment, targeting increased investment from corporations of a ‘vibrant nature’. These ‘angel investors’, as a quid-pro-quo to supporting innovation, will be offered several benefits such as a stamp duty waiver on certain market transactions and a waiver of direct and indirect taxes. It is also proposed that a capital gain waiver be granted on several types of investments, including those relating to universities, centres of excellence, and institutions engaged in sciences, technologies, mathematics, engineering, finance, management, law and legal services.

In addition, steps were taken to reform the primary and secondary education system. Public sector investment in R&D was doubled to around 2 per cent of GDP. And for the first time, the government inducted and empowered two industry captains to lead two of the government’s key initiatives. Sam Pitroda, widely regarded as the architect of the communication revolution of the 1980s and 1990s, was appointed as advisor to the Prime Minister on innovation and infrastructure over and above his role as the chairman of the knowledge commission. And the appointment of Infosys co-chairman, Nandan Nilekani, to the national ID project also marked the government’s intent in executing some of these ambitious programmes.

If the first 44 years after Indian independence laid the foundations for self-sufficiency and mental infrastructure, the next 19 years and beyond defined the globalisation era by addressing the need for economic connectedness with the rest of the world. Opening up the market was a fundamental shift in India’s polity. The globalisation drive of the last 20 years has brought in the funds, technological know-how, standards, best practices and most importantly a mindset that have allowed India to compete on a global scale, with the result that a new generation of capitalists are now entering the workforce. A new India is being launched from a new platform. India’s democracy, rule of law and institutions can now sustain new forms of growth. The seeds of innovation-led growth have already been planted. The key challenges that policy-makers, administrators and bureaucrats will face in the next 37 years up to its anniversary centennial in 2047 will be to make innovation mainstream and provide the missing connection between India’s mental infrastructure and its physical infrastructure. India has to make sure that it is able to enhance rural GDP, which has a direct impact on rural migration and rapid urbanisation. Until this is tackled, India’s physical infrastructure will continue to be under siege.

Having discussed the state of India’s affairs at the micro and macro level since independence, it is worth exploring the rational foundations to determine a link between innovation and national competitiveness. I do this in the following chapters. Given the gap between business economists and academic economists on this topic, and in the wake of the global financial crisis, the definitions of national competitiveness are mired with opinions from various schools of thought. The data from the various surveys I have analysed and used in my deductions may have favoured the prospects of countries like India and China that have emerged from the global financial crisis relatively unscathed. In this context, a review of country-level data over a wider time window will provide the background to the predictions I make.

1.NBN aims to achieve connectivity to 99.8 per cent of homes in Australia using fibreoptic technology. Australia has fibreoptic connectivity in some metropolitan areas such as Sydney.

2.NREGA (National Rural Employment Gurantee Act), http://nrega.nic.in

3.Using a cautious, slow strategy to wear down the opposition; avoiding direct confrontation (see Fabian Society).

4.Laski was a prominent proponent of Marxism and had a massive impact on the politics and the formation of India, having taught a generation of future Indian leaders at the LSE. It is almost entirely due to him that the LSE has a semi-mythological status in India. He was consistent in his incessant advocacy of the independence of India.

5.The Fabian Society is a British intellectual socialist movement, whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy via gradualist and reformist, rather than revolutionary, means. The Society laid many of the foundations of the Labour Party and subsequently affected the policies of states emerging from the decolonisation of the British Empire, especially India.

6.Fabian philosophies involved slow gradual change in social engineering – changes undetected by people until all the phases are over.

7.Amartya Sen received the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1998.

8.Zakaria, F. (2006) India: Asia’s Other Superpower Breaks Out, Newsweek.

9.Tharoor, S. (1997) India: From Midnight to the Millennium. New Delhi: Penguin Books India Ltd.

10.Mehta, S. (2004) Maximum City: Mumbai Lost and Found. Knopf.

11.Random notes on the Economy of India, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_India

12.Welch, J. & Byrne, J.A. (2001) Jack: Straight from the Gut. Business Plus.

13.Geiger, T. & Rao, S.P. (2009) The India Competitiveness Review, The World Economic Forum, http://www.weforum.org/pdf/ICR2009.pdf