Introduction

This is the moment when we must build on the wealth that open markets have created share its benefits more equitably. – Barack Obama

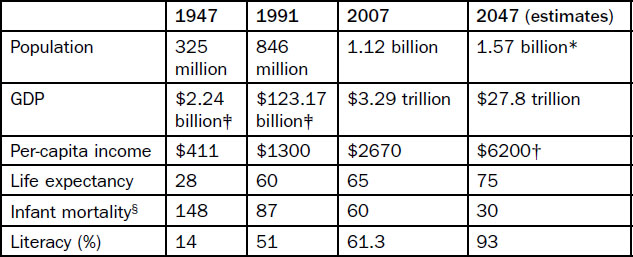

By India’s independence centennial 2047, India’s 100 years of independence will have been characterised by three tipping point eras bound by four tipping point years: 1947, the year of independence from Britain; 1991, the year that launched breakthrough economic reforms; 2007, the year that marked the end of the tenth five-year plan and the beginning of the eleventh five-year plan; and 2047, the independence centennial year (Table 1.1). Of these milestone years, the 2007 tipping point and beyond is the least documented.

Table 1.1

Modern India’s 100-year journey is consistent with the growth of most G7 countries

*World Bank Estimates

†at today’s exchange rates

‡at 1996–7 prices.

§Deaths per 1000 births.

Source: Aggregated from Ministry of Statistics, Government of India; World Bank Economic Indicators; International Monetary Fund;

The decade beginning in 2007, the start of the eleventh five-year plan, has been a new beginning for Innovation. It has been declared the decade of innovation and infrastructure – two key national agendas highlighted for India’s global competitiveness. In 2008, the process to establish a National Innovation Act was begun, public R&D spending doubled to 2 per cent of GDP and was well on its way to 3 per cent, and education expenditure doubled to 6 per cent of GDP, with a 50 per cent outlay for higher education and training. The New Millennium Indian Technology Leadership Initiative (NMITLI) programme, the country’s largest collaborative R&D effort involving 80 industry partners, 175 R&D institutions and 1700 researchers, received funding of US$155 million as part of the eleventh five-year plan. To further the momentum, India will need tremendous focus on inclusive innovation to energise rural entrepreneurship and increase rural GDP. India will also urgently need to set up a National Innovation System that ensures funding and coordination amongst different R&D initiatives.

Innovation is the only way for India to nurture its organic growth through local entrepreneurship. A closer look reveals that having missed several opportunities since 1947, it is largely playing a game of catch up in most sectors. Those sectors that have prospered, namely IT, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and auto industries, are now burdened1 with the task of hauling the nation towards prosperity. Although sustaining global competitiveness is critical, innovation in India is inextricably intertwined with rural development and rural entrepreneurship for the development of India’s poor. India’s growth industries also need nurturing and support to grow through innovation. In the meantime sustaining India’s export- orientated industries such as steel and textiles is critical. The challenge will be to balance the diverse needs of global competitiveness and economic growth while improving rural GDP. A portfolio view of innovation is a necessity.

From another perspective, there is the global dynamic impacting India externally both geo-politically and demographically. As I outline in Chapter 3, US domination in global innovation is waning due to its current financial crisis and the consequent drop in private R&D spending in the short and long term, through lowering of public funding in R&D and decreasing enrolment in science and maths education. Private R&D constitutes three-quarters of US R&D spending. For the first time, in 2009 the net number of utility patents granted by the US Patent and Trademark Office to countries, firms and institutions outside the US has outweighed those granted to US companies and R&D institutions. At the same time, China, India, Singapore, Malaysia and Korea have enhanced their contribution to global innovation by way of upping R&D investments, focusing on science and technology, and growing a resident scientific talent. The impact is telling. Innovation is gaining an Asian face. China, India and Malaysia are annually being granted utility patents much faster than any other country in the world. India, with the third largest scientific workforce in the world, is a significant contributor to this shift. This shift in innovation activity in Asia coupled with the economic activity of two of the world’s largest economies – India and China – is creating permanent ecosystem changes for innovation globally. For example, India will have a larger say in international intellectual property rights, standards-setting and commercialisation of intellectual property. These trends, resulting from what I call the geodynamics of innovation, is a critical external imperative that is largely ignored today. What happens when the ecosystems of innovation – institutions of funding (venture capital funds, angel investors, etc.), institutions of R&D, institutions of higher learning and private industry – cross borders to locations where talent is available and innovations are predominantly happening? New ecosystems are created in new locations where innovation and economic activity are dominant. This is the geodynamics of innovation – a phenomenon where the ecosystems of innovation move towards the geographical locus of innovation and vice versa. I use the term innovation geodynamics here to describe the confluence of the geographical, geopolitical, social and demographic forces that produce the right climate and ecosystems for entrepreneurship and innovation in a region.

In Chapters 4–7, I switch between the outside-in and inside-out perspectives to balance biases when I compare and contrast India across the tipping point eras. These Chapters highlight the painful but welcome transition into liberalisation and economic liberation. They highlight the resulting issues of a stark and visible dichotomy between the rising middle classes and the poor, and elicit the dovetailing of globalisation- and innovation-driven growth. By the time we approach Chapters 8 and 9, which provide prescriptions for nationalising and formalising engagement with innovation, it will be clear that India’s emergence as an innovation superpower is an inconspicuous one. It is built on the science and technology foundation laid earlier in the years immediately after independence, funded by the post 1991 economic growth, and sustained by momentum set in the eleventh five-year plan and beyond. These measures are powered by a younger workforce, a new breed of entrepreneurs, by world-class industries that have emerged to embrace competition, by a middle class demanding accountability from the government, a rural population that benefits from the economic upswing and by an economy that is lending India a bargaining position globally, attracting the right set of infrastructure, resources and talent to set up a viable innovation ecosystem.

In Chapters 2 I look at the different perspectives to analyse modern India as a source of intellectual capital. It becomes apparent that India is a complex and diverse nation characterised by a three-tier economic and social structure each with its own issues and challenges. One-third of India’s population live on under a dollar a day. A little more than one-third of the population are in transition to becoming middle class within the next three decades. And one-third are the current middle class. Recognising that the fundamental needs of each tier is different is a good starting point. One soon realises that the tiers are inter-dependent. None of the three tiers will move forward unless the issues and challenges of the bottom tier are addressed first. Getting one-third of the population out of poverty and providing them with social security is not just a moral priority but an infrastructural necessity, as Chapters 8 on inclusive innovation shows. In other words, improving rural GDP is a necessity. There are vertical issues, such as education and employment, that transcend the tiers. Unless India’s massive population of young people across all three tiers2 is provided with education, training and employment, India will implode, leading to insurgency and civil unrest. Health and infrastructure also cut across the tier structure.

I also argue that it is unfair to evaluate a country of India’s size and complexity before at least 100 years of sovereign history has passed. In fact, all the G7 countries have had at least a 120-year history of sovereignty, with the US leading with 233 years of development history behind it. Although Korea and Japan have emerged as leading economies from similar beginnings in a shorter time they did not inherit a huge population that was largely illiterate, undernourished and dependent on government subsidies. Also, India did not inherit a well-endowed nation from British rule. In fact India’s development (in terms of infant mortality, life expectancy and per-capita income) has only improved since independence. For example, by the onset of the eleventh five-year plan, literacy in India, a key indicator of socio-economic progress, grew to 66 per cent from 12 per cent at the end of British rule in 1947. Comparing India with China is fairer. China, having launched its reforms 13 years before India, maintains a rough lead of a decade and a half. It also takes considerable time for change to percolate through a nation. For example, in Chapters 2, I point out that the US took 70 years to achieve 100 per cent electrification from the time electricity was first developed in 1873. Many ignore the fact that India has more favourable metrics than many developed countries for the same time elapsed since establishment of their independent sovereignty. In fact, India’s progress will be faster than many of today’s developed nations given its ability to leapfrog several stages of legacy technologies and infrastructure that bog down developed nations today. For example, telephone exchanges in rural India run on more advanced technologies than those of the G7 countries.

In Chapters 9, I call for the creation of a National Innovation System where innovation is formalised and systemically ingrained in the running of the economy through a portfolio approach defined by structural differences in social configuration, the need for global competitiveness and inclusive growth. A National Innovation System should define the participants, cohere policy, funding, priority, collaboration and outcomes across the three-tier economic structure that will be paramount for the next 40 years. Its biggest role will be to set the agenda for innovation inputs, namely talent, training and infrastructure. It will pull together the inputs required to fuel innovation leading to a well-oiled national system capable of creating an innovation culture and ecosystem. The definition of the National Innovation System, its constituents and an operating framework is a prescriptive recommendation and key contribution to this book. In many ways, the National Innovation System described will look similar to those that exist in the US, Switzerland and Denmark.

Throughout, I draw attention to innovation – be it grassroots innovation, social, incremental or disruptive innovation – as a key platform for problem-solving to address many of the issues India faces today. For example, the impact of a solar-powered water purification system, a $1000 biometric-based ATM, or a 50-cent recombinant DNA- based vaccine for Japanese encephalitis will be priceless. And finally, the book encourages raising the profile of innovation as a culture that needs to be brought about in schools, firms and most importantly as a platform of the people, for the people, and run by the people – as democracy is. Innovation rarely happens in wood-panelled boardrooms or an emotionally charged political rally but it can come from a sterile laboratory, a university or Panchayat-level3 self-help groups. That should be a focus for a long time to come.

1.India is one of the few countries in the world with high economic growth rates that does not have correspondingly high per-capita income.

2.Fifty per cent of India’s population are below the age of 25, and 40 per cent are below the age of 15.

3.Panchayat: a decentralised form of Government in which each village is responsible for its own affairs, as the foundation of India’s political system.