India’s place in the new world order

The economic dominance of the US is already over. India is becoming a powerhouse very fast. – Peter Drucker

In 2004, Peter F. Drucker told Fortune Magazine that ‘India is becoming a powerhouse very fast’. Coming from the man who is widely regarded as the father of modern management, this could easily have been the biggest single endorsement for the Indian story. Drucker’s revolutionary teachings in management still hold good in other areas. But does Drucker’s view on India still matter?

In the autumn of 2009 I was at the Metropolitan Club in New York listening to the man who coined the term ‘Emerging Markets’. Antoine Van Atmael is author of The Emerging Markets Century: How a New Breed of World-Class Companies is Overtaking the World.1 Atmael and I were co-presenters at the World Emerging Multinationals Congress, a conclave of investors, corporate executives, academics and planners interested in the growth of the emerging markets held for the first time in New York.

Atmael noted that for decades, the US (and the rest of the ‘developed world’) had over-consumed and over-leveraged but also under-invested and under-saved while emerging markets had under-consumed, invested in their infrastructure and become the world’s suppliers, lenders and even investors. The end result, he said, was that the financial crisis did not spread to most emerging markets but what we witnessed was a ‘halfglobal’ crisis. The emerging markets did not cause the economic crisis and were more resilient than thought. The crisis did not stop the rise of emerging markets but only accelerated it. As Atmael put it, ‘the G7 is now reduced to a dinner before the G20’. In fact with the G20 growing in stature since the 2008 Washington summit, its leaders announced on 25 September 2009 that the group will replace the G8 as the main economic council of wealthy nations.

All this has happened in the last 25 years. Twenty-five years ago, China was an experiment, Russia was still peddling the Cold War with the US, India was a bureaucratic mess and Brazil was an economic mess. Atmael concluded that the world may not be flat as hoped, but it is definitely tilting.

Although the bulk of global income, as expressed by world GDP, is generated in the developed countries, their net GDP contributions are diminishing. With only 16 per cent of the world’s population, developed countries generated 73 per cent of the world’s nominal GDP in 2006, compared with 80 per cent in 1992. These numbers would have only skewed further with the global financial crisis when the developed world entered into recession and dragged the global economy into recession by 2009.

From another perspective, developed countries have been a leading source of foreign direct investment (FDI), at one time accounting for over 80 per cent of global outflow. Recently, the outward FDI from developing and transition economies has increased significantly, led by China and the emerging markets. This trend will only strengthen in future. Developing countries that have achieved current account surpluses are becoming important providers of capital for the rest of the world. For example, when Facebook recently scouted for additional funding, it went to unlikely corners such as the UAE and Russia. In July 2009, Anil Ambani’s Reliance Big Entertainment company signed a deal that would provide $825 million funding for Steven Spielberg’s DreamWorks Studios to make six films a year for global audiences. Globalisation signifies the increasing importance of cross-border activities for human welfare across the globe, not limited to economic factors such as international trade and FDI, but extending to other basic aspects of human activity such as knowledge, institutions and organisational culture.

Trends show that as a direct result of globalisation, the number of multinational corporations (MNCs) from the emerging markets has grown too. Today, there are an estimated 78,000 MNCs globally, with more than 780,000 foreign affiliates. The number of employees in foreign affiliates worldwide has grown dramatically: it reached 73 million in 2006, up from 25 million in 1990. Sales by foreign affiliates quadrupled during the same period, from $6 trillion in 1990 to $25 trillion in 2006. Their assets reached $51 trillion.

In 2005, all but four of the top 50 MNCs had headquarters in the Triad (the EU, Japan and the United States). In 2005, the foreign assets of the top 50 largest non-financial companies from developing economies climbed to $400 billion, from $195 billion in 2002. There was also a shift in the growth centres and with it the economic power centres.

In the 1980s and 1990s, a seismic shift was taking place in the global economy, in which China was claiming the lion’s share of the world’s manufacturing and India was rapidly shoring up services. In the initial stages of this shift, popular opinion was that these countries were gobbling up the jobs primarily driven by cheap labour. Cheaper labour has definitely been a trigger and will be for some time, but foundational structures required for entrepreneurship and innovation have also been set up. India and China are ordering their backyards for the biggest surprises. With two of the world’s largest economies, India and China, embracing economic reform roughly about 13 years apart in the 1990s and late 1970s respectively, globalisation needs to be looked upon as one of the major transformative forces in contemporary society. However, it is important not to look at the relationship between globalisation and internal changes in countries today as a deterministic process, in which the only role left for policy-makers at the national level is to adapt national institutions and policies to given global trends. Rather, there are also the increasing role of knowledge in the global economy, knowledge creation and utilisation, and how these interact with institutional and cultural factors.

Globalisation has become an irreversible trend and will continue to fund growth of developing countries like India in the foreseeable future. Over the last 40 years, through globalisation that began with the outsourcing of expensive manufacturing and then services, America progressed its economic growth and American incomes have risen faster than those of any other major industrial country. Globalisation has not only provided economic development in developing economies but has also catalysed permanent structural transformations. For example, the relative contributions of agriculture, industry and services to global output change dramatically in the process of development; in the long run, the relative weight of agriculture tends to fall, and that of services tends to increase. China and India reflect this trend, characterised by countries such as Japan and the Republic of Korea when they were developing 30 years ago, and grew by applying high-level technology in a low-wage environment, thereby lowering unit labour costs.

Table 3.1

Top five developing country exporters by category of service ranked on 2005 export values

Source: Adapted from UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics 2008.

India and China with their large and resourceful populations were once dominant and it appears will be dominant again, taking their traditional place at the heart of the global economy. The rise of Europe, North America and Japan has been a brief interlude in world history. The surprise, perhaps, is that China and India never went away; for most of the ancient and modern eras until the 18 th century they were the twin pillars of the world economy, bastions of wealth and progress. Angus Maddison, the British-born economic historian, is probably one of the few qualified to give a statistical narrative to complement descriptions of the world’s past. Maddison’s calculations, which appear in his masterwork, The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective,2 show that 2000 years ago China and India between them held 59 per cent of the world economy (of which India had 33 per cent). At the birth of Christ, India made up one-third of the global economy, China more than one-quarter. Another book by Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics, published in 2004 by the OECD studies the growth of populations and economies across the centuries. Among other things, it confirms Adam Smith’s view that China and India were at a higher or comparable level with Europe from the 1st century until the late 18 th century. History, it seems, is on China and India’s side.

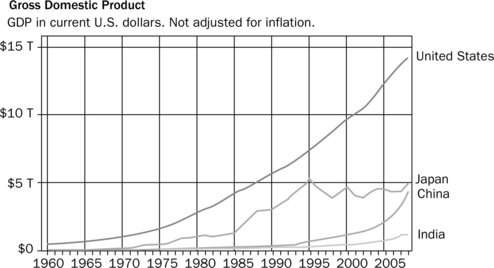

Asia is huge. After all, it’s the world’s largest and most populous continent, covering 8.6 per cent of the Earth’s total surface area and 29.9 per cent of its land area. Its more than 4 billion people comprise approximately 60 per cent of the world’s population. With the bulk of the growth in Asia – of 9 and 6 per cent annual growth, respectively – attention will remain focused on China and India for a while. China at No. 2 and India at No. 4 are two of the four largest markets in the world with the US at No. 1 and Japan at No. 3. Even now, China and India together are barely one-third of the United States in terms of GDP (Figure 3.1). That leaves significant headroom for growth. China and India’s journey over the next 40–50 years will be a fascinating one, full of opportunities and pitfalls.

Figure 3.1 China and India together make up barely one-third of the United States in terms of GDP Data source: World Bank, World Development Indicators – Last updated November 20, 2009, courtesy of Google.com

In 2009, China overtook Japan in terms of GDP. The engine of future growth has been turned on and not surprisingly it is powered from Asia. It is led by globalisation but sustained by innovation. And it’s not just from India and China, but also Singapore, Malaysia, Korea and Taiwan. However, by sheer size, scale and impact, India and China lead the charge by reasons of both geographical and demographic advantages.

When HSBC decided that from February 2010 onwards its chief executive, Michael Geoghegan, would be based in Hong Kong, it said it was readying the group for the shift in the world’s centre of economic gravity from the west to the east. Consistent with that trend, Robyn Meredith, writing on the rise of India and China, noted: ‘In this decade, a clear pattern emerged: China became factory to the world, the United States became buyer to the world, and India began to become back office to the world.’3 She names Beijing, Washington and New Delhi as where global power will lie very soon. Their climb will have been astonishing.

India’s and China’s emergence have redefined the economics of global competitiveness, forcing the US and other developed nations to look at their core competitive advantages afresh. For Americans, improving the education system and investments in basic research have emerged as major challenges. But the bigger challenge that Asia posed was that Asians outnumbered the US in terms of talent. There are more Indians and Chinese who are college-educated and yet are willing to work for one-tenth that of Americans. In the short term it may seem a win-win situation in which more than half the savings of Chinese manufacturing and India’s services now go to American consumers, and the Chinese and Indians are becoming wealthier than their parents who received meagre agricultural incomes.

The real threat is when fewer Americans will be able to afford current prices for Chinese goods and Indian services and India and China would have moved into design and branding of innovative products and services. High-calibre Indians and Chinese are already finding the US less attractive as opportunities are quickly growing in their own countries. Many of their expatriates are choosing to return. Thus, the US is increasingly going to need to rely on its own talent, which is ill prepared. The outsourcing of manufacturing and services have benefited the American public in terms of low prices for goods and services but the serious concern is that of the roughly 130 million jobs in the US only about 20 per cent (or 26 million) pay more than $60,000 a year. The other 80 per cent pay an average of $33,000. This ratio is not a good foundation to provide a strong middle class and a prosperous society.

India and China have followed opposing strategies for development. While China’s growth has been fuelled by a heavy dose of FDI, India has followed a far more organic method and has concentrated more on the development of the institutions and indigenous capability that support private enterprise by building a stronger economic infrastructure to support it. But China has had a head start. China put itself on the path towards growth in the late 1970s and India in the early 1990s. There are some who argue that India’s path has distinct advantages and that there are distinct differences in the way they are developing. Yasheng Huang is one of them. Huang is Professor of Political Economy and International Management at Sloan School of Management at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and is widely regarded as an expert on Chinese experiments with capitalism. He points out that India’s companies use their capital far more efficiently than China’s; they benchmark to global standards and are better managed than Chinese firms. He believes that despite India’s position behind China economically, India has produced dozens of world-class companies like Infosys, Ranbaxy and Reliance because of these fundamentals. Huang also attributes this difference to the fact that India has a real and deep private sector (unlike China’s many state-owned and state-funded companies), a clean, well-regulated financial system and the sturdy rule of law.

China’s economic reforms began in 1978 when it rebuffed the communist system. It broke up collective farming and that alone resulted in a quadrupling of agricultural output. The government then released most food price controls, and 80 per cent of farmers then repaired and improved their homes. Collective farming was first developed in the USSR in 1917. Stalin’s collectivisation drive of 1929–33 wrecked a flourishing agricultural system. It was adopted by China in 1953, under Mao Zedong. It was further pursued during the Mao years of the ‘Great Leap Forward’, which was an attempt to rapidly mobilise the country in an effort to transform China into an industrialised communist society. Collective farming existed as a practice in Isreal, for example. Known in Israel as the kibbutzim, the difference was that in Israel, kibbutzim was traditionally created through voluntary collectivisation and farms were governed as democratic entities unlike in China and the USSR. Chinese-style collective farming forced farmers to pool their land, domestic animals and agricultural implements and the profits of the farm were divided among the farmers. In China, production had originally fallen 40 per cent when the farms were collectivised and resulted in mass starvation.

Deng Xiao Ping (Mao’s successor) then toured Singapore and was greatly impressed. Special economic zones suspended anti-business laws, taxes were lowered, and rules were streamlined for factories making goods for export. In addition, promotions for local officials were linked to the number of jobs created in this way. Unlike India, China was quick to build required roads and utilities. In addition, the Chinese government insisted that overseas companies use and teach local workers their latest techniques as a condition to operate in that market. By 2000, 30 per cent of the world’s toys came from China. In less than 5 years this figure had risen to 75 per cent. China exported computers and other technology-driven products worth $180 billion in 2004, up from $20 billion in 1996. It exported $9 billion of automotive parts in 2005, up from $1.3 billion in 2001.

India began allowing foreign investment over a decade after China and in a hesitant and erratic manner after a new government was confronted with the reality of near bankruptcy. It devalued the Rupee by 20 per cent, lifted restrictions on imports, raised interest rates to 11 per cent to encourage saving deposits, and eliminated export subsidies. State-owned banking, airline and oil companies were opened to private investors, and important anti-monopoly limits were eliminated for most companies while steps to end red tape, corruption and taxes were introduced. Despite that, in 1996, a corruption scandal brought a return of left-leaning leaders. Sending left-leaning government leaders to China helped break the resulting impasse on developmental issues.

To be fair, privatisation was a government initiative. It was probably the last resort as the economy had tanked by 1990, to the extent that national gold reserves were used to raise liquidity in the economy. Aviator turned politician, Rajiv Gandhi, who stepped into his mother’s shoes following her assassination in 1984, was the last man standing in the Gandhi dynasty until his assassination in 1991. Many commentators believe Rajiv set the ball rolling for his successor, Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao, and his team (including now Prime Minister Manmohan Singh) to unleash economic reform. In a sense they redefined India. When Rao famously said, ‘The full freedom to dream the way you like came in 1991, not 1947’, he was right in that India was doing the right thing at the second opportunity. Elsewhere the USSR was dismantled driven by Perestroika and Glasnost and the Cold War ended in 1991. The Berlin Wall came down two years earlier. An atmosphere conducive for collaboration and a new romance with prudent capitalism ensued. India kept liberalisation and privatisation at the core of its focus despite mounting opposition from every corner. And it worked.

Steady lowering of import duties on technology, raising foreign equity limits in Indian firms, actively privatising loss-making public-sector firms, and building a banking and financial framework to support liberalisation helped India grow its exports in the services and knowledge sector first and then manufacturing. Outsourcing computer programming to India began in 1998 as a result of surmounting global needs for Y2K code re-hash. Today, it is a $70 bn export industry. India’s pharmaceutical industry is a $30 bn industry, including the domestic market. India is the world’s fourth largest producer of pharmaceuticals by volume, accounting for around 8 per cent of global production, employing around 500,000 people with around 270 large R&D-based pharmaceutical companies in India, including multinationals, government-owned and private companies. In the last 25 years China has lifted some 400 million of its 1.3 billion people out of a dollar a day poverty. India hasn’t. For that reason alone, India’s growth will characteristically have to be innovation led. There is also healthy competition between India and China, and this is becoming of key interest to the US and other nations interested in the balance of power in the region. In 2002, I was invited by the Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT) to speak on India’s software engineering practices and the rise of India’s software industry. My audience was the university’s postgraduate and doctoral students in information technology. Indian software firms had just begun setting up shop in China. One student rather bluntly asked, ‘why are you taking our jobs?’ All the questions I received were on the potential impact of revenue leakage to India, job prospects, and the covert and overt rationale behind Indian firms wanting to work in China. The Chinese are very careful about who they chose to work with. But at the same time the spirit of the Chinese young people to conquer the English-speaking world is both fascinating and determined. Even in casual conversations, students could be seen using pocket translation devices to translate difficult words, and I have never witnessed such keen interest to learn and to be involved in any of the universities I have spoken in, including those in the US and here in Australia.

A few days prior to the BIT lecture, I was attending sessions as part of the China Beijing International High-Tech Industry Week, which attracts international exhibitors, visitors and industry leaders in addition to researchers like me. The High-Tech Industry Week was inaugurated by the Chinese premier and a number of his colleagues at the Great Hall of the People. To be held at this venue, the High-Tech Industry Week had to be high on the government agenda. Built in 10 months in 1959 on the western side of Tiananmen Square, the Great Hall of the People has a total floor space of more than 170,000 square metres and comprises 300 meeting halls, lounges and office rooms with a seating capacity of over 10,000. The office of the standing committee of the National People’s Congress is also located here and this is where the Chinese legislature, the National People’s Congress, assembles for deliberations on state affairs. The delegates were told of the government’s rising interest in space sciences, biotechnology, stem cell research, and electronics and communication. Against the backdrop of some of this architecture and some of the unique history associated with it, you wonder in amazement that you are standing on the same ground that created history, controversy and global interest in the turnaround China has achieved since Chairman Mao.

At dinner tables and private conversations, people were more objective and critical of China’s policies. In one instance I was seated next to a senior official from the Ministry of Foreign Trade & Economic Cooperation. We spoke openly about the revolution, the reforms taking place, the divide between the rich and the poor, and the exemplary quality of Chinese manufacturing. It was at this table that I learnt that the one-child policy is coming back to bite the Chinese in a unique way. My host explained that for average single-income families there could be as many as six dependants under the one-child policy. Parents of a couple are often supported on the one income along with the couple’s lone offspring.

As much as Asia’s emergence and China’s dominance in particular is captivating, India’s astonishing transformation from a developing country into a global powerhouse is a fascinating story and one that cannot be ignored. Many, like David Smith, author of the 2007 book The Dragon and the Elephant, China, India and the New World Order, believe that Asia is returning to the global prominence4 it has had for over 2000 years. Smith believes it is more complicated than that, or we should be looking forward to the return to prominence of all ancient empires. Civilisations rise and fall. There is nothing fated about the fact that once-great powers will reassert themselves; indeed, the opposite is more often true, as in the case of ancient Egypt, Greece or Rome. It was common until relatively recently to regard history as more of a burden for India and China than a harbinger of future greatness.

The dynamics in the region are therefore important. ‘India is everywhere: on magazine covers and cinemas, in corporate boardrooms and on Capitol Hill’ writes Mira Kamdar, a Senior Fellow at the World Policy Institute and author of Planet India. There are two Indias, Kamdar suggests in her book.5 ‘The point isn’t that the new India does not exist. It does, and it is genuinely exciting and brimming with potential’, she writes. ‘At the same time the old India is hardly dead and gone.’ The new India is being born out of the old.

Many Western businessmen go to India expecting it to be the next China. But India will never be that. China’s growth is a product of its quick, efficient, determined, all-powerful government. If Beijing decides that the country needs new airports, eight-lane highways or gleaming industrial parks, they are built within months. It courts multinationals and provides them with permits and facilities within days. It looks good and, in many ways, it is that good, having produced the most successful case of economic development in human history.

India’s growth is messy, chaotic and largely unplanned. Unlike China’s growth, it is not top-down but bottom-up. It is happening not because of the government, but largely despite it. India does not have Beijing and Shanghai’s gleaming infrastructure, and it does not have a government that rolls out the red carpet for foreign investment – no government in democratic India would have that kind of autocratic power. But India has vast and growing numbers of entrepreneurs who want to make money. And somehow they find a way to do it, overcoming the obstacles and bypassing the bureaucracy. ‘The government sleeps at night and the economy grows’, says Gurcharan Das, former CEO of Procter & Gamble in India.

An upswing in the 2000s

Goldman Sachs’s BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) report6 is now passé. But when it was published in 2003, it was the first to project both a timeline and the means by which India would achieve global leadership. The BRIC report will long be remembered for projecting that over the next 50 years India will be the fastest-growing of the world’s major economies (largely because its workforce will not age as fast as the others).

The report calculated that in 10 years India’s economy will be larger than Italy’s and in 15 years will have overtaken Britain’s, by 2040 India will be the world’s third largest economy and ten years later it will be five times the size of Japan’s and its per-capita income will have risen to 35 times its current level. Predictions like these are not without reason. Today very few contest such predictions.

Indian companies are growing at an extraordinary pace, posting yearly gains of 10, 15, 20 and 25 per cent when their counterparts and those they supply to are operating on stimulus provided by their governments.

Today, India is the fourth largest economy in the world, ranking above France, Italy, the UK and Russia. India has the third largest GDP in Asia. It is also the second largest among emerging nations. India has jumped 16 places to claim the 34th position in the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook in 2004 as it gained significantly on various parameters, such as economic performance, government efficiency and business efficiency. In 2009, IMD placed India 29th.7 The World Economic Forum also places India 29th among the 144 most innovative nations.

However, 20 years ago there were no comparisons of what would demonstrate hope for a country as large as this. Dharavi, which is marketed by one tour company as ‘the biggest slum in Asia’ and of ‘Slum Dog Millionaire’ fame, occupies 432 acres of swampy land several miles north of the tourist areas of Mumbai. Among its chaos of open drains, tin-roofed shacks and capillary-like alleyways, 1 million people live and work often in appalling conditions.

Contrast this with Infosys’ 450-acre global training centre 1000 km south of Mumbai in Mysore, where manicured lawns, swimming pools, amphitheatres, multiplexes, training rooms, offices, conference rooms and boardrooms are set in lush greenery lined with an array of water bodies and fountains set in Greek-style architecture, the largest state-of-the-art corporate residential training facility in the world. This facility offers residential training to some 20,000 simultaneously and some 50,000 engineers annually for the global software industry. (India’s cricketers train here as well.)

There is no doubt that India bore the brunt of protectionism but the new India now has some distinct advantages as a result. India’s industry has leapfrogged legacy technologies and business processes to become what it has become. Much of the industrialised world is plagued with ageing infrastructure and technologies that have bogged them down with high modernisation costs. Indian firms are being built on far more advanced technologies and systems that could last for nearly half a century. For example, by the end of 1990, Maruti Udyog, India’s largest car manufacturer, had become one of the largest customers of SAP in the world and a poster child for SAP in the automotive sector. India’s telecommunication industry is another case in point where India has leapfrogged technology redundancies.

Alongside this industrial awakening, Indian entrepreneurs started to emerge from their hibernation to build some of the finest companies in the world. Firms such as Tata, Birla or Godrej that transcended the tipping point eras consolidated their businesses in new-found economic freedom. Others in the services sectors, particularly in IT, boomed after 1990. India began gaining a seat on the global stage largely due to globalisation and the opportunities it presented firms from the developed world.

A decade ago the idea of Indian IT services industry reaching revenues of US$20 billion was a dream. Today the industry has tripled in size. The global delivery model, where Indian companies disaggregated the software development life cycle in a bid to distribute the execution of the various pieces to cost-effective locations, was a disruptive innovation from Indian industry. Innovative techniques, processes and systems were introduced to manage gathering, design, development and deployment. The success of the model prompted those incumbent leaders in the sector – IBM, Accenture, EDS (now part of HP) and CSC – to follow suit and build their own global delivery models. That journey started when people such as N. R. Narayana Murthy, a software programmer, put together $250 and started Infosys in his small apartment in 1981. Infosys leveraged and co-innovated the global delivery model to service Global 2000 firms. Its market capitalisation, at one point, was more than US$30 billion. Infosys has become the poster child of India’s IT leadership and the pride of the nation today. Today both IBM and Accenture have in excess of 50,000 staff each in India.

In all the strategic planning conferences that happen at Infosys annually in Mysore that I have attended, Chief Mentor, Narayana Murthy has repeated one key message that the focus at Infosys is to build a corporation that should last at least 100 years. Before 1991, with a few companies such as Tata and Birla, India did not have an old corporate history. It is now a young nation with young corporations that do not carry a baggage. At the same time, young corporations are also vulnerable to all kinds of pressures. For many new corporations, delivering a service has been the easier path. Very few companies have been bold enough to launch new products globally. This is beginning to change, albeit slowly. India’s manufacturing ventures, too, have differed significantly from the Chinese model. China’s contract manufacturing is characterised by the fact that only about 10–20 per cent of a product’s US retail value stays in China; the bulk goes to the designer, e.g. Intel and Microsoft, and brand-name retailers.

Consider India’s car industry. Once characterised as producing outdated 1940s models sometimes referred to as ‘fossils on wheels’, India is emerging as a global centre of innovative automotive design. Once the government allowed FDI up to 100 per cent with no minimum investment requirements for new entrants, the automotive sector has attracted more than $15 billion in investments and today employs 600,000 workers directly and 12 million indirectly.

India now also designs electric vehicles with state-of-the-art energy management systems, transmission systems, and even finished cars that are now designed and produced in India by firms such as Mahindra & Mahindra and Tata. Some of the vehicles are exported. Mahindra enjoys a 4 per cent market share in the US and a 7 per cent market share in Australia for its state-of-the-art tractors, which are challenging incumbents on both price and quality. Tata Motors recently launched an electric version of the Nano aimed at domestic and international markets. A World Bank report8 points out that Mahindra & Mahindra spent only about $120 million to develop its best-selling SUV, Scorpio. This is one-fifth of what it would cost in Detroit. Tata Motors also recouped its development costs within a year on the Tata Ace, a small last-mile goods-delivery truck that costs about $2500. Tata has now rolled out the world’s smallest car – the Tata Nano – priced for the bottom of the pyramid. Every year Japan awards the coveted Deming Prizes for managerial innovation, and over the last five years they have been awarded more often to Indian automotive companies than to firms from any other country, including Japan.

Innovation geo-dynamics: structural shifts

Interestingly, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the geography of Asia has contributed to the dynamics of globalisation like never before. A UNDP report on transnational corporation asserts that the geographical origin of the new multinationals favours South, East and South-East Asia, followed by Latin America and South Africa.

India’s and China’s grip over globalisation and dominance in Asia has only strengthened over the years. By the middle of the 2000s, the combined domination of India and China had for the first time captured the attention of policy-makers worldwide. Because the US’s technology leadership is threatened by Asia, a comprehensive agenda for technology innovation has never ranked any higher that it is on the federal government’s imminent agenda.

The National Intelligence Council (NIC),9 a high-level CIA think-tank, has consistently pointed out that the US’ position as the world’s technology innovation leader may be severely weakened by two Asian superpowers, China and India, in the next 15 years.

The reasons highlighted by the NIC are that America’s R&D investment as a percentage of GDP is at an all time low. Private sector R&D investment dropped by $8 billion in 2002, the largest yearly decline in nearly 50 years. Today only about 5 per cent of US college students graduate with engineering degrees. In the 1990s funding for basic research began to decline slowly. Bell Labs, for example, had 30,000 employees as recently as 2001; today under the ownership of Alcatel-Lucent it has 1000. Such figures are symbolic and symptomatic. With upstream invention and discovery drying up, innovations capable of generating industry-level potential have thinned to a trickle. Very few institutions enjoy the legendary status that Bell Labs, Xerox PARC and RCA Labs did in their hayday or the research at IBM, NASA or DARPA. Many of the classic scientific research labs were funded by companies with virtual monopolies and strong, predictable cash flow. With the increasing focus on shareholder value that started in the 1990s, companies could no longer justify open-ended research that might have a near-term impact on the bottom line.

The US can no longer compete with foreign manufacturers on price and cost reduction. They have to compete using innovation, research and development. Many experts feel that the US is simply not doing enough in R&D and the US is falling into an innovation gap. The following forecast on American R&D from the Battelle Institute and R&D Magazine10 show that R&D budgets haven’t grown at all: total spending on US R&D for 2009 was $383.5 billion – a 1.75 per cent increase over 2008. Total Government spending stood at $99 billion – a 0.34 per cent increase. Industry expenditures on R&D are expected to reach $258 billion, a 2 per cent increase over 2008. Academia and non-profit organisations make up the remaining expenditures of $31.5 billion. In fact, even though $383.5 billion is a lot of money, in constant dollars, the total R&D budget has not grown much since 2000 and 1.75 per cent growth in 2009 is less than the rate of inflation. Given the global financial crisis the national position on R&D is unlikely to change.

Before 1980, the federal government largely funded R&D but now industry R&D spending is almost three times that of the federal government. In the last eight years, the federal government has also shifted basic research dollars from the physical sciences to the life sciences. This is great for biotechnology industries, health sciences and pharmaceuticals, but not at the expense of basic sciences. The bulk of the private industry’s share of the R&D forecast of $258 billion, or 67 per cent of the total, is increasingly devoted to product development and less on the basic research that is needed for future innovation. Also, since the mid 1980s, there has been a serious drop in the number of US graduates in the physical sciences, engineering and mathematics. However, the proportion of foreign students coming to US schools to graduate in these disciplines is growing, and they go back to work in their countries and often end up working for US competitors.

While postulating that science can create millions of new jobs, a Business Week report11 on the future of R&D that appeared in September 2009 stated that the US needs 6.7 million jobs to replace losses from the current recession and an additional 10 million to keep pace with population growth and to spark demand over the next decade. In the 1990s the US economy created a net 22 million jobs; from 2000 to the end of 2007 the rate plunged to 900,000 a year. The biggest concern, the report said, was that outsourced jobs have been replaced by millions of low-wage service jobs in fast food, retail and the like. Adrian Slywotzky, a partner with Oliver Wyman and the author of the Business Week article, says ‘The US growth engine has run out of a key fuel – research.’ As a result, for the first time, there were more patents issued by the US patent and trademark office to patents filed from outside the United States.

On the other hand, Asia continued to reshape the innovation equation riding on globalisation, giving it less of a ‘Made in the USA’ character and more of an Asian look and feel. This is the background to the question, ‘Will the US be flattened by a flatter world?’ This has led the media to postulate a combination of solutions and theories in the US to counter the emergence of Asia as the primary source of innovation.

China and India may even influence international intellectual property rights and demand alternatives to the US dollar as a reserve currency, and assert heavier influence in the international monetary system and international trade organisations. China’s and India’s need for energy and raw materials may also force them to ally with nations averse to the US such as Iran, Venezuela and Sudan. Thus, the US is going to find itself with less and less international influence in the coming years.

Meanwhile, by having the fastest growing consumer markets, firms becoming world-class multinationals and assuming greater science and technology stature, Asia looks set to displace current economic and technology superpowers as the focus for international economic dynamism. As Clyde Prestowitz, a former Reagan bureaucrat, puts it, Asia’s face has about three billion new capitalists.12 Consider this: Asian finance ministers have re-considered establishing an Asian monetary fund that would operate along different lines from the IMF, attaching fewer strings on currency swaps and giving Asian decision-makers more leeway from the ‘Washington macro-economic consensus’.

In terms of capital flow, Asia has accumulated large currency reserves, currently in the region of $2200 billion in China, $1000 bn in Japan, $450 bn in Russia, $270 bn in India and $219 bn in Korea. A basket of reserve currencies including the Yen, the Renminbi and possibly the Rupee probably will become standards. More recently, Russia and China, part of the emerging BRIC economies, have been actively discussing the replacement of the US dollar as global reserve currency. A senior Adviser to the Chinese State Commission for Regulation of the banking sector has recently stated that it would be ‘more practical’ to use the international monetary system with four or five major currencies of various countries, rather than a system dominated by a supranational currency. In the same conference, Russian Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin said that the Yuan will be one of the world’s currencies in the next 10 years. Russia and China are already considering shifting to mutual settlements in national currencies in the energy sector.

Washington, Beijing and Delhi: new power centres?

Asian Governments are also devoting more resources to basic research and development and are attracting applied technology from around the world, including cutting-edge technology. India recently doubled its spending on R&D to 2 per cent of GDP. These measures are boosting its high-performance sectors. The US already anticipates that the Asian giants may use the power of their markets to set industry standards, rather than adopting international standards set by bodies promoted by Western nations. The international intellectual property rights (IPR) regime will be profoundly moulded by IPR regulatory and law enforcement practices in East and South Asia. Some experts say that China will protect IP aggressively when it has its own IP.

There is also an expanding Asian-centric cultural identity that is having a profound effect on Asia’s dominance. A new, more Asian cultural identity is likely to be rapidly distributed as incomes rise, communications networks are established and social networks expand. Demand for cross cultural entertainment is just one example of this trend. Chinese kung-fu movies have fans amongst English-speaking audiences around the world. Bollywood song-and-dance epics are viewed throughout Asia, Europe and North America. Korean pop singers are already popular in Japan and Japanese anime have many fans in China. Even Hollywood has begun to reflect these Asian influences to the extent that very few movies leave India and China out of their scripts. Multiculturalisation is increasingly becoming an Asian story.

What about innovation? CISCO’s CEO John Chambers once said that when he looks at China and India, he sees two countries each with more than a billion people methodically focusing their efforts on improving the maths and science skills of their top students. For every new engineering graduate in the US, which has a much smaller population to begin with, there are five in China. ‘In China and India, they clearly understand that if they get the engineers, then they get the managers, then they get the companies, then they get the innovation’, Chambers pointed out.

John Chambers is not alone. Several senior US executives including Jeff Immelt of GE and Craig Barrett of Intel are worried about the US losing its competitive edge due to a shortage of engineers and scientists. They reckon that the increasing size of the technologically literate workforce in these countries, and efforts by multinational corporations to diversify their high-tech operations into these countries, is fuelling return of a talented pool to their home countries and those who would have considered living and working in America.

Further compounding the talent scenario, there is a worldwide shortage of PhDs and as the costs of college tuition increase, this problem will grow in America, industrialized nations and emerging nations. China produces some 13,000 PhDs annually, not enough to sustain the level of innovation China needs to upgrade its civilisation. In India, the computer industry is strong but short of PhDs. India’s educational institutions produce 7000 PhDs per year in all disciplines, of which only about 1500 are from the sciences. The US produces 1000 computer scientist PhDs per year, a large percentage born in India or China. Many PhD students are offered jobs before their PhD is completed, and this is likely to be a continuing trend.

Moreover, future technology will be represented by interdisciplinary areas that result from the convergence of biological sciences, information technology, smart materials and nanotechnologies. Although these are new, and have life-defining potential, the skills to support the development of these areas are hard to come by. Information technology will alter business practices and models – in fact it already has if India’s influence in the global IT industry is anything to go by. These technology trends – coupled with agile manufacturing methods and equipment as well as multidisciplinary development in technologies to manage water, energy and transportation – will help China’s and India’s prospects for joining the ‘First World’.

Both India and China are investing in basic research in these fields and are well placed to be leaders in a number of key areas. Europe risks slipping behind Asia in creating some of these technologies, burdened by adverse demographic constraints. The US is still in a position to retain its overall lead, although it must increasingly compete with Asia and may lose significant ground in some sectors. China is asking how to make innovation rapid and effective as a strategy for growth. The Chinese science and technology ministry already recognises that its enterprises need to become the centre of innovation because they will respond better to the market. India is now well positioned to employ policies that can leapfrog stages of development, skipping over phases that other high-tech leaders such as the US and Europe had to traverse in order to advance. India now has an Innovation Act in the making that allows the government to fund and reward indigenous innovation. It has a National Knowledge Commission entirely focused on innovation and infrastructure. It has raised investments in science and technology and is upgrading all its higher institutions of learning. India is also re-visiting the engines that supply the inputs to its national innovation network, such as primary education, and improving the lot of the poorer regions in a way that attracts talent.

Rapid technological advances outside the US would enable other countries to set the rules for implementation of intellectual property rights (IPR), information security, moulding privacy, design and standards. International IPR enforcement is already on course for dramatic change. China and India, because of the purchasing power of their huge markets, will be able to shape the creation and development of international policies, as observed in the most recent Copenhagen summit on climate change.

The attractiveness of these large markets will tempt multinational firms to overlook IPR indiscretions. For example, it is widely acknowledged that Microsoft and Autodesk has a huge installed base in India amassed through piracy in the 1980s even before these companies began actively selling in these markets. And such infringements have had only a positive impact when these companies began focusing on these markets. Many of the expected advancements in technology are anticipated to be in medicine. There will be increasing pressure from a humanitarian and moral perspective to release the property rights for the good of all.

Robyn Meredith, Fareed Zakaria and other recent authors, for example Mira Kamdar and Nandan Nilekani,13 capture the essence of the fascinating Indian story. Walt Rostow, an American economic historian, gives the reasons why some countries rise suddenly. He defined the conditions for what he called ‘the take-off into self sustained growth’,14 notably high levels of investment and the large-scale transfer of workers from the predominantly agricultural economies to manufacturing, high levels of productivity and reliable non-agricultural jobs. As a result, China has become an attractive destination for manufacturing jobs, and the path for services was paved to India.

The size of the Indian workforce outnumbers America’s entire population but the challenge for India is to enable them to be on par or better than the American workforce in terms of productivity and innovation. India has a workforce of 484 million, 273 million of whom work in rural areas, 61 million in manufacturing and about 150 million in services, according to the Boston Consulting Group which recently conducted a study on the country’s services sector. What weighs India down in getting its workforce up to speed in terms of productivity? India has over 750 million people in the lower middle class – equal to the population of Africa – including around 300 million below the poverty line. In other words, India has the dual challenge of nurturing and meeting the aspirations of a workforce roughly 1.5 times the population of the US while balancing the developmental needs of a population the size of Africa. Every decision and development initiative will bear the brunt of that statistic.

As varied as the impact of globalisation on nations has been in participating countries, India has a trump card that it hasn’t yet played; it is building a new nation from under the cover of globalisation that is emerging silently from within the old India that everyone is familiar with – chaotic, disorganised and ill-structured. The new India, miniscule as it may seem, is driven by entrepreneurship, innovation and a new found appetite to take on the world. Growth itself is taking a new dimension.

India realised that its destiny lay not just in being a low-cost supplier of the world’s goods and services, but in being an international leader in the supply of goods and services by embracing innovation and R&D-based excellence. It realises that tomorrow’s world is about innovation. For example, within weeks of Apple’s launch of the iPad, a Hyderabad-based company, Notion Ink, announced India’s first Android-based touchscreeen tablet nick named Adam. At the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Notion Ink, started by a group of six IT engineers and an MBA graduate, launched the Android device, which sports a 10.1-inch touchscreen, Bluetooth, USB charging, Wi-Fi connectivity and a 3-megapixel digital camera with auto focus, and video recording options. It is expected to hit the stores soon. Such announcements are becoming more frequent.

Non-traditional businesses like IT services and pharmaceuticals have grown significantly in the last two decades and are recognized as having arrived on the global stage. Much of its growth through globalisation and infusion of global best practices is now spawning new industries and leadership in sectors through innovation. For example, market research company Frost & Sullivan estimates that the R&D outsourcing market for information technology in India alone will touch $9.1 billion in 2010. The R&D outsourcing market for telecom in India is expected to reach $4.1 billion in 2010.

On the human resources front, India has the seventh largest pool of R&D personnel, and its large cadre of non-resident scientists, technologists and entrepreneurs infers that it has third largest pool of scientific and technical manpower in the world. These individuals are increasingly engaged with their home country. A reverse brain drain has begun in some sectors. Whether it is rural or corporate entrepreneurship, India has shown itself to excel in this regard. The Indian diaspora, strongly represented in the United States, also provides an excellent source of everything from information and advice to access to markets, technology and financing as India’s activities increase in sophistication. India is a world centre for many digital services, a location where ‘anything that can be sent offshore’ can be done very cost effectively. From this base, India is becoming a centre for innovation for multinational companies, which have already established around 400 R&D centres to draw on its scientists and engineers. Over 100 Fortune 500 companies around the world, including GM, 3 M and Novartis, have set up their research and development centres in the country in the last 5–10 years primarily buoyed by India’s cost and skills edge over the industrialised world. During the first phase of its development, India’s relatively large numbers of talented young people have attracted global corporations to include India as a global innovation hub from which outsourcing of innovation could be executed. In the second phase, India is taking the lead, leveraging learning from the globalisation experience to drive innovation that will lead the nation towards the next century.

In 2005, India set up a Knowledge Commission to look into the issue of enhancing the quality of human capital for science, technology and innovation. The government believes that investments in institutions of higher education and R&D organisations are as important as investments in physical capital and physical infrastructure. The upgrading of India’s institutions of higher learning began with an infusion of over $20 million in grants to the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bangalore way back in 2005, which enjoys a high reputation as a centre of excellence in R&D. In that announcement, then Finance Minister P. Chidambaram, himself a Harvard Business alumni, stated that the government would work to make the IISc a world-class university. Since then many more investments have gone into setting up new institutions of learning and upgrading existing ones.

At a time when the global average expenditure on education is 4.5 per cent of GDP, India is increasing its education budget from 3.6 to 6 per cent of GDP, and more than half of the investment will go into primary education. This augurs well for higher education in the country and education in general. To fund education further, new proposals are being considered to attract up to 50 per cent FDI in higher education. Echoing the political direction set in New Delhi, local and state governments are recognising innovation by expressing a willingness to set up innovation foundations, decentralised governance and encouraging patenting at the grass roots level with the primary focus being employment and reducing the gap between the rich and the poor.

Kirit is 19 years old and is in his final term of his engineering degree course. He is the son of a CEO of a successful multinational pharmaceutical company in Bangalore. Kirit has seen the world and he is a privileged middle class teenager unlike many Indians of his age. He has seen some of the world already because his family can afford holidays overseas. And his choices are reasonably well informed. I ask him what he plans to do after he finishes his degree. He makes it clear that he may go into higher education but that he plans to work for an Indian company in India. He makes a point of mentioning that he is not planning to go to America. I can see why.

Twenty years ago, stifled by a lack of opportunity, India’s best university graduates would have planned their exit to greener pastures even before their graduation year. India’s brightest students also left the country for higher education and the prospects that followed. India now provides educated young people like Kirit with a plethora of opportunities, including higher studies or a lucrative career early in life. Twenty years ago, studying, working and living in America ranked highly for most middle class Indians, but that trend is waning. The brain drain from India to America meant that by the early 1990s more than one-third of America’s scientific, medical and engineering workforce had roots in India. In fact, many analysts have asked why Indians do extremely well outside their own country. The answer was that they lacked the ecosystem to perform in India that America offered them – like risk buffers, ancillary industries (for prototypes, testing, etc.), venture capitalists, test labs and a marketing infrastructure.

There has been a reversal of that trend with many Indians returning to India as prospects at home have improved. Approximately 10,000–15,000 professionals are currently returning to India from the US annually. In 1995, more than 60 per cent of IIT graduates migrated to the US. Today, this figure is less than 20 per cent.

The global financial crisis and its rebound led by India and China have established India’s credibility and influence on global markets. As I write this, most Indian companies are hiring new employees, and many companies have rolled out significant pay revisions to its workforce. India has received many overseas applications for employment including the United States. Despite its short-term setback of the late 2000s, America remains the country Indians want to build for themselves. Indians understand America as a noisy, open society with a chaotic democratic system like their own. Many urban Indians speak American English thanks in part to America’s entertainment industry. They are familiar with the country and often actually know someone who lives there. By that measure alone, most Americans would probably be surprised to learn that India is, by all accounts, the most pro-American country in the world.

A Pew Global Attitudes Survey, released in June 2005, asked people in 16 countries whether they had a favourable impression of the United States. A stunning 71 per cent of Indians said yes. Only Americans had a more favourable view of America (83 per cent). The numbers are somewhat lower in other surveys, but the basic finding remains true: Indians are extremely comfortable with, and well disposed toward, America.

India still sends its students to America for higher education in Business, Management, Mathematics and Computer Science. Education is big business in America, contributing approximately $17.8 billion a year to the US economy, through expenditure on tuition and living expenses, according to the US Department of Commerce. In 2008/9, according to the Open Doors 2009 survey by the Institute of International Education, India remains the leading place of origin for the eighth consecutive year, increasing by 9 per cent to 103,260 migrant students. When the number of international students at colleges and universities in the US increased by 8 per cent to an all-time high in the academic year, for the first time the number of institutions reporting increases in students from India did not outweigh those reporting declines (29 per cent reporting increases and 29 per cent reporting declines). Of the largest host institutions (those 121 responding institutions enrolling more than 1000 students), 50 per cent reported a decline for students from India and only 31 per cent reported an increase.

At the same time, the survey pointed out that India had become one of the favourite destinations for American students. With the number of Americans studying abroad increasing by 8.5 per cent to 262,416 in the 2007/8 academic year, a record number, China, India, Japan, South Africa and Argentina emerged as the most favoured educational destinations. The report also showed that the number of students to nearly all of the top 25 destinations increased, notably to destinations less traditional for study abroad: China, Ireland, Austria and India (up about 20 per cent each).

As India grows as a centre of global innovation, a new US–India relationship will emerge, one in which India is seen as both a partner and an effective competitor to the US in the global marketplace. At the National Academy of Sciences June 2006 conference on India’s Changing Innovation System, Ralph Cicerone, President of the Academy, noted that advances in information and communications technology are creating new opportunities for the US and India to benefit from the complementarities in their innovation systems.15

India’s growth has largely been organic, fuelled by entrepreneurship at the grass roots. FDI has helped but in a way that supports local entrepreneurship. Today India has the ability to become the next America. India has the youngest population on the planet and a middle class as large as the population of the entire US. America has proven that wealth can be created quickly, although it hasn’t done it in a way that is environmentally sustainable or equitable. India may well be the new America, a land of opportunity. The future may well be run from Delhi, Beijing and Washington.

1.van Agtmael, A. (2007) The Emerging Markets Century: How a New Breed of World-Class Companies is Overtaking the World0. Simon & Schuster Free Press.

2.Madisson, A. (2001) Development Centre Studies. The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. OECD.

3.Meredith R. (2008) The Elephant and the Dragon: The Rise of India and China. W.W. Norton & Co.

4.Smith, D. (2007) The Dragon and the Elephant, China, India and the New World Order. Profile Books, pp. 8–13.

5.Kamdar, M. (2008) Planet India: The Turbulent Rise of the Largest Democracy and the Future of Our World. Scribner.

6.Wilson, D. & Purushothaman, R. (2003) Dreaming With BRICs: The Path to 2050. Goldman Sachs.

7.IMD Competitiveness Year Book, http://www.imd.ch/research/publications/wcy/index.cfm

8.Dutz, M.A. (ed.) (2007) Unleashing India’s Innovation. World Bank.

9.The National Intelligence Council, http://www.dni.gov/nic/NIC_home.html

10.Collins, M. (2009) The Innovation Gap, http://www.manufacturing.net/Articles-The-Innovation-Gap-020309.aspx

11.Slywotzky, A. (2009) How Science Can Create Millions of New Jobs, Business Week, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/09_36/b4145036678131.htm

12.Prestowitz, C. (2006) Three Billion New Capitalists: The Great Shift of Wealth and Power to the East. Basic Books.

13.Nilekani, N. (2008) Imagining India: Ideas for the New Century. Penguin.

14.Rostow, W.W. (1956) The take-off into self-sustained growth. The Economic Journal, 66:261, 25–48.

15India’s Changing Innovation System Achievements, Challenges, and Opportunities for Cooperation, Reports of a Symposium, 2007, http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=11924&page=3