PEST and SWOT analysis of international interlibrary loan

Abstract:

In this chapter, we use two business analysis techniques PEST (Political, Economic, Social and Technological) and SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) to identify external and internal factors influencing the challenges and benefits of international interlibrary loan.

Introduction

International interlibrary loan is heavily influenced by external political, economic, social and technological factors. These factors, in turn, have a daily impact on how effective and efficient we can be in sharing library materials across borders. In this chapter, we look at two commonly used business analysis techniques, PEST (Political, Economic, Social and Technological) and SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats), to gain a clearer picture of how these issues play a role in the functions and processes of international interlibrary loan.

PEST/SWOT are multi-step analysis techniques used to identify outside factors influencing the success of a company or institution as well as the internal health of that company or institution. One step included in a typical PEST and SWOT analysis is the listing of issues affecting an industry or business. This step of the SWOT and PEST analysis is the focus of this chapter.

PEST is an acronym for Political, Economic, Social and Technological factors. It refers to external influences generally beyond our control that have an effect on an industry or company. A PEST listing of factors influencing international interlibrary loan can help us better understand the barriers to successful international resource sharing as well as give us the opportunity as a community to find solutions to these constraints. In comparison, SWOT is an acronym for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats. A SWOT listing can show us what internal factors we can exploit to provide successful international interlibrary loan and what weaknesses exist in our current international interlibrary loan practices or processes that could be improved.

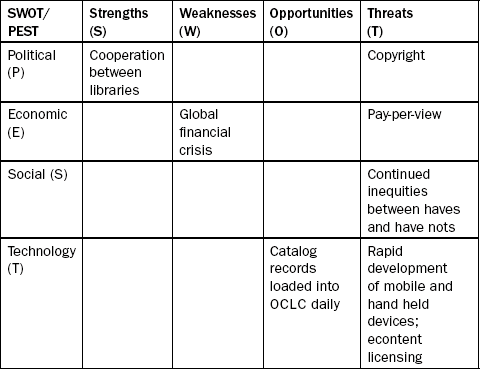

It may be helpful to show how SWOT and PEST analyses might be diagrammed, as shown in Table 3.1.

In this instance, SWOT analysis is employed to discuss strengths (S), weaknesses (W), opportunities (O) and threats (T) of global resource sharing. Each of these four components can also be further examined according to a PEST analysis, which refers to political (P), economic (E), social (S) and technological (T) determinants.

PEST analysis of international interlibrary loan

Political

Political influences which may affect international interlibrary loan can broadly be characterized in the following ways: (1) the overall political climate within a particular country or region, (2) the role government plays in influencing libraries in that country, and (3) a country’s relations with the rest of the world.

The overall political climate in a particular region might include the relative stability or instability of a country due to war or revolution, change in governance, factors such as natural disasters and a country’s current isolationist or expansionist government philosophy. A recent example of the toll taken by war on libraries is exemplified by the fate of the Iraq National Archives and Library which was burned and looted in the wake of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. The region remains dangerous, including to National Library employees. The ability to provide any library services, let alone interlibrary loan, can be difficult if not impossible in situations such as these.

An example of the consequence of political upheaval on interlibrary loan is seen in the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and its subsequent effect on the Russian State Library (RSL). As Nadezhda Erokina relates in her article, ‘The Russian State Library: Russia’s National Centre for Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery,’ the impact of which

caused radical social and economic changes which dramatically influenced the library system and the nationwide ILL system developed by the RSL collapsed. In the mid-1990’s, ILL struggled to survive in Russia. In certain periods, financial shortages and budget deficits prevented the RSL from sending ILL requested items by mail to other libraries. But the most difficult issue was the longer delays in sending back books ordered from foreign libraries. (Erokina, 2010: 38)

Further, during the Soviet era, interlibrary loan between eastern bloc countries was well organized. After the fall, newly established countries were left to their own devices to establish individual interlibrary loan programs, with mixed results.

Another example is South Africa where transitioning from the apartheid era

… left a legacy of unequally distributed resources, with some libraries being very well supported financially, while other libraries that were allocated to separately serve the black population of South Africa were atrociously under-resourced. Traditional interlending services were one way to help bridge this gap. With the change in government, political and strategic priorities also changed, focusing on addressing and redressing this imbalance. (Baker, 2003: 1)

Natural disasters such as the earthquake in Haiti on January 12, 2010, or the summer 2010 flooding in Pakistan which destroyed 250 libraries in the region, can have a serious effect on all library services including international interlibrary loan. When a natural disaster or social movement causes political disruption in the region, mail and telecommunication service are often interrupted for lengthy periods of time, until infrastructure can be rebuilt or restored.

The geopolitics of knowledge sharing and a country’s current political philosophy can also impact libraries and their interlibrary loan services. Interlibrary loans in the United Kingdom and France have been influenced in recent years by these policies. Due to the United Kingdom’s ‘Enterprise Culture’ public services have been deeply scrutinized and mandated to incorporate not only cost recovery but also revenue earning income. This environment directly affects the services of the British Library, the primary lender of British materials (Bonk, 1990).

Joachim Schopfel recently described the impact that French government policies have had on libraries in that country. In France, universities’ administrative and financial autonomy facilitated new experiences, concepts and models that could be transposed on a national level. At the University of Metz, for example, activities in the framework of this current political climate played out along these lines:

In the context of the ongoing (liberal) reform of the French public administration, he [Colinmaire] carried out a detailed cost/benefit analysis with four major results: suppression of internal invoicing … reduction of external invoicing, out-sourcing of document supply, re-orientation of acquisition policy to digital resources. (Schöpfel, 2005: 57)

The role that government plays in influencing libraries in a country can include oversight, policies, regulations, and red tape which can either help or hinder interlibrary loan. In many countries such as England, Denmark, France and Spain the national libraries shape library policy and are major providers for international borrowing and lending. Countries without a central library may suffer from the absence of organized interlibrary loan systems and networks. Inadequate government coordination, particularly in the area of information technology (IT) infrastructure has a trickle-down effect on libraries and interlibrary loan. In Nigeria, for example, IT-related projects are dispersed throughout several different ministries (Igwe, 2010) resulting in an often crippling lack of coordination and effectiveness.

A government’s role in regulating activities that effect libraries such as copyright can also impact interlibrary loan. A prime example of this is Germany’s recent copyright litigation which has seriously hampered that country’s ability to provide online document delivery to other countries. Conversely, a government’s reluctance or inability to update copyright policy, especially in terms of electronic and media materials, leaves many libraries in the position of individually trying to interpret copyright guidelines, licensing and contract law.

Finally, international interlibrary loan can be impacted by a country’s relations with the rest of the world. Tensions between countries can influence the success or failure of cooperative resource sharing. Unequal partnerships with more developed countries such as those between Botswana and South Africa (Datta, 1991) or between the states of the former Yugoslavia (Mocnik, 2001) can develop. Conversely, political tensions may also be the impetus for libraries to create or join cross-national consortia that promote resource sharing.

Economic

Economic factors to consider when thinking about international ILL can include the current international economic climate, the economic climate at a national level and the growing discrepancies between the economic situations in developed and developing countries.

The current international financial situation has had a serious effect on libraries and interlibrary loan. Library acquisitions budgets have been slashed, placing more of an emphasis on resource sharing than ever. Downsizing of library staff in the face of these cuts has also had an impact on overall operations and a library’s ability to provide both domestic and foreign interlending in a timely manner.

At a national level libraries and their interlibrary loan departments may experience inadequate funding or the lack of institutional financial support. For example, an irregular influx of monies had a significant effect in Russia where reduced funds distributed in small amounts and at irregular times of the year made managing acquisitions extremely difficult (Kingma and Mouravieva, 2000).

Common economic concerns between all countries which affect interlibrary loan are the costs of postage, equipment, personnel, and telecommunications. In developing countries, however, these concerns are felt at an even more basic level with the cost of electricity and frequent power outages hindering library functions in countries such as Ghana (Agyen-Gyasi, 2009) as well as relatively scarce resources for IT investment.

Further, in many countries such as South Africa, economic problems are not equal between rural and cosmopolitan areas. With the National Library of South Africa lacking funding to support interlibrary loan, a commercial entity, Sabinet-Online, has taken the lead in supporting interlibrary loan in that country. However, as a for-profit organization its services are often beyond the reach of small, rural libraries.

Social

Social factors influencing interlibrary loan vary greatly between developed and developing countries. In developed countries a high rate of literacy and computer savvy coupled with an understanding of the importance of scholarship and research fuel the need for materials including those provided through interlibrary loan. In developing countries, social factors can hinder libraries and interlibrary loan. These factors can include a high rate of illiteracy, a lack of a national language, a lack of a tradition of books and libraries and, on an even broader level, the lack of buildings and facilities.

Overall, if the current interlibrary loan literature, with many articles published from interlibrary loan practitioners in both developed and developing countries, is any indication, the realization of the importance of scholarly research is well understood worldwide. In Pakistan, for example, understanding the need for researchers to compete in the international market is crucial, requiring modernization that provides access to the latest information resources. This global flow of information empowers Pakistani scholars to be part of the research conversation (Bhatti, 2008). In Turkey, where more than 44 percent of the population is under the age of 25, the number of students as well as the growth in university research output has resulted in increased interlibrary loan and document delivery activity (Erdogan and Karasözen, 2009). Likewise, Botswana reports sophisticated demands of a growing readership with specialized skills (Datta et al., 1991).

Technological

Technology, and particularly the development of the Internet, has had a profound effect on the ability of libraries to share resources across borders. However, the success of interlibrary loan is greatly affected by the information technology (IT) infrastructure in any given country. More importantly, technological concerns can also vary widely amongst developed and developing nations. This discrepancy is often called the ‘Digital Divide.’ In developing nations, where the cost of technology can be prohibitively high, many countries lack technological infrastructure including a dearth of functional servers, application platforms and software applications, Internet access, broadband development, a skilled IT labor force, a limited number of computers and funds to service and maintain computers and servers. As noted above, even more basic concerns include insufficient electricity and telephone lines as well as frequent and unpredictable power outages. A study in Islamic Sciences Centers in Iran indicated that in 43 percent of the centers, ‘… there is only one telephone line and 5 percent do not even have one’ (Abazari and Isfandyari-Moghaddam, 2010: 193).

As libraries all over the world have discovered, technology has provided us with greater ease of discovery and management of requests. At the same time, technology alone does not reduce inequities or remove political, economic or social barriers to access.

SWOT analysis of international interlibrary loan

Strengths

One of the primary strengths of international interlibrary loan is its people, and most especially, the sharing mentality of these interlibrary loan practitioners. The interlibrary loan community is known for its attitude of partnership, cooperation and collaboration and willingness to not only share materials but to also share knowledge and skills. This sharing culture is evidenced by our listservs, workshop offerings and conference participation. Further, the interlibrary loan community has wonderful support and infrastructure from our professional associations such as IFLA, as well as national and regional library associations and consortia.

Other strengths include rich library holdings as well as online national union catalogs in many countries, worldwide catalogs such as OCLC’s WorldCat, ILL software management packages such as ILLiad, Relais and CLIO, as well as document transmission software such as Ariel and Odyssey.

Our ability to harness technology to our advantage whether it be in organized resource sharing through systems such as OCLC or in simple email transactions between international libraries is also a major strength.

Weaknesses

The list of obstacles and challenges in international interlibrary loan is a long one (Massie, 2000; Spies, 2001; Seal 2002; Baich et al., 2009; Atkins, 2010). Most of the barriers identified in earlier publications still exist today. These include financial issues, language barriers, lack of a sharing culture, history or tradition, a shortage of uniform procedures and electronic access, imperfect interoperability systems, the absence of national union catalogs, no uniform copyright regulations, and shipping issues including slow delivery times and fear of loss and damage.

Financial constraints include the cost of shipping an item overseas and difficulties with payment methods. It can be difficult to pay or charge for an item from overseas if OCLC IFM, IFLA vouchers or credit cards are not an option. Bank transfers are difficult and many institutions’ accounting departments cannot handle this type of payment. Also, exchange rates can be a hindrance. Negotiating a transaction cost can also be difficult if the borrower and lending library staff members do not speak a common language.

Language barriers can affect location of an item if an interlibrary loan staff member does not understand the language of a requested item and cannot verify it. Unfamiliar character sets can further hinder a staff member’s ability to track down an item.

The absence of a tradition or history of library cooperation exists in many countries (Spies, 2001) including apathy on the part of lending libraries. Further, many libraries will not accept international requests or will lend only portions of their collections. The sometime overreliance of borrowers on too few lenders can lead to ‘donor fatigue’ on the part of some lending libraries. Also, lack of support of interlibrary loan by an ILL unit’s institution or country can have an impact. This lack of support can often result in insufficient staff to manage ILL activities (Cimen et al., 2010).

Non-existence of an international interlibrary loan system is another weakness. While most developed countries have formal interlibrary loan guidelines and infrastructure, developing countries may have informal and disorganized ILL procedures. Slow development in uniform ILL software can have an effect as seen in Iran which has experienced differences in packages, a paucity of national standards in designing library software and no support for Z39.50 protocols (Chelak and Azadeh, 2010). Also, while many libraries have adopted library automation systems oftentimes these systems do not include an ILL module (Cimen et al., 2010). Lack of awareness of other libraries’ policies can also be a hindrance as reported for the Norwegian ‘Bibliotek’ database (Gauslå 2006).

For want of a critical mass of online metadata for the world’s libraries global resource sharing can also be hindered (Spies 2001). Cataloging has a distinct impact on interlibrary loan when a deficiency of uniform cataloging or standards and the inconvenience of moving between physically disparate catalogs make both discovery and retrieval inefficient and more costly (Butler et al., 2006). Lack of a national union catalog has been listed as a hindrance to interlibrary loan in Iran (Chelak and Azadeh, 2010) and Turkey (Cimen et al., 2010). Without a national union catalog, confirmation of the existence of an item, accurate known locations, availability at those known locations, licensing controls and authorization becomes more difficult.

Copyright is another area of concern. This topic is discussed below in the ‘Threats’ section of this chapter.

Geography plays a major role in international interlibrary loan. Domestic interlibrary loan within a country or region can be hindered by the distances materials need to travel within a country such as in China (Jia, 2010) or by natural barriers as in the ILL between Caribbean theological libraries (Taitt, 2005).

Shipping has long been, and continues to be, a weak and vulnerable spot in international ILL. In addition to high costs, materials are away from their home institutions longer than domestically loaned items. Many ILL staff members fear that this keeps materials away from local patrons for unacceptably long periods of time. The reliability of postal and courier services is another concern as is the fear that items will be lost or damaged in the mail. The mechanics of actually shipping a book to another country often perplex interlibrary loan practitioners and mail room staff who must negotiate a path through various courier options and customs offices.

Opportunities

Political, economic, social and technological factors and events all have had a profound impact on libraries and interlibrary loan. With that said, great opportunity also exists. It is forcing us as a community to cooperate even more than ever before. No single library can be entirely self-sufficient.

Technologically, the increasing growth of IT support in all countries is allowing patrons to access materials internationally. This is true in countries as diverse as Turkey (Cimen et al., 2010) and Singapore (Chellapandi et al., 2010). Advanced network facilities are also helping developing countries to gain Internet access.

Many interlibrary loan practitioners see the growth of ‘purchase on demand’ programs a plus for their users. Integrating acquisitions into the ILL workflow allows us to provide materials for our patrons more quickly and in a more cost-effective manner.

Threats

Acquisitions budgets in many libraries have been hit by both cuts and increased subscription prices. This situation, resulting in fewer items purchased and canceled journal subscriptions, has resulted in a decrease in the number of items available for interlibrary loan.

Resource sharing and more specifically interlibrary lending – both domestic and foreign – is not an inexpensive service. For a number of years, many libraries have absorbed the costs of shipping and delivery, equipment and software upgrades, and staff processing time into their own budgets. There is now increasing pressure from administrators, governing bodies and other stakeholders to provide ILL services on either a cost-recovery or profitgenerating basis.

A developing threat to interlibrary loan is that of ebook and ejournal licensing practices. Unfortunately, online does not also mean free. The overwhelming majority of ebook publishers do not permit ILL in their licensing agreements. While ejournal licenses have been somewhat more lenient than ebooks, the frequent use of date-based embargoes limits what can be loaned. Likewise, licensing agreements that permit lending but demand that articles be printed and then rescanned before transmission to a borrowing library take time and are not environmentally friendly. Pay-per-view threatens free or affordable access to electronic content and is an issue to which libraries must pay attention.

Another persistent danger to international interlibrary loan as it is currently practiced is the lack of consistent international copyright guidelines. Some countries such as the United States pay copyright fees for items borrowed. Other countries such as England pay copyright on items loaned. This can result in some article requests not having their copyright royalties paid at all and some being paid twice. Understandably, this situation irks publishers and may result in future lawsuits and restrictions. Further, as seen in Germany, recent copyright litigation can shut down a country’s ability to provide interlibrary loan of documents internationally at all.

An example

As an example of how a modified SWOT analysis might play out in a library setting can be seen in the following example:

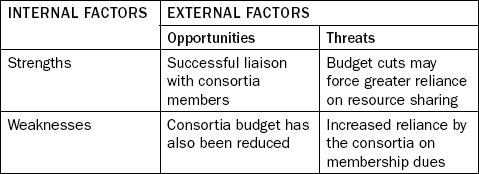

a library consortia in a large urban area of the United States noted that a series of grants was going to become available in the near future. The criteria for these external funding opportunities seemed to emphasize interlibrary cooperation and resource sharing. This trend was perceived by consortia as a potential opportunity that also coincided with its own record of cooperative activities among several of the region’s largest academic libraries, traditionally known for their independence. The detected trend in funding criteria (opportunity) along with the consortium’s work as an effective liaison (strength) forms the upper quadrants of the diagram. The library consortium also predicted that its member institutions were facing increasingly severe budget cuts (threats). Unfortunately, the consortium’s own financial profile had also shifted in the last few years, to the point it was more dependent on member fees than in the past (weakness). (Kearns, 1992, 12)

It should be noted that SWOT and PEST analyses do not solve problems; rather, they are a means to identify and clarify issues facing an organization or agency. In the example shown in Table 3.2 after performing a SWOT analysis, the consortia may decide to pursue external grant opportunities, based on a better understanding of both the risks and rewards this activity might include.

Summary

This chapter introduces the basic structure and precepts of SWOT and PEST analyses to interlibrary loan practitioners. These methods provide ways of looking at the current environment, while also thinking about the future. By identifying and clarifying some of the important issues facing libraries and information agencies, it becomes possible to frame a strategic planning process as well as to engage staff and administrators in a focused discussion of a single issue or an entire service or product. SWOT and PEST analysis can be used to facilitate a common understanding of a specific issue or a possible future. Ultimately, these discussions and the information they produce may be used to improve or defend important core functions and services.

Bibliography and further reading

Abazari, Zahra, Isfandyari-Moghaddam, Alireza. Establishing an Information Network among Islamic Sciences Centers in Iran: A Feasibility Study. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(3):189–194.

Adeyinka, Tella. Attitudinal Correlates of Selected Nigerian Librarians towards the Use of Information Technology. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve. 2008; 18(3):287–305.

Agyen-Gyasi, K. An Evaluation of the Reprographic Services at the KNUST Library, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve. January 2009; 19(1):7–20.

Ahenkorah-Marfo, Michael, Teye, Victor. Sustaining Information Delivery: The Experience of Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Library, Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve. September-October 2010; 20(4):207–220.

Albelda, Beatriz, Abella, Sonia. The ILL Service in the Biblioteca Nacional de Espana. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):49–53.

Alemna, Anaba A., Cobblah, M. The Ghana Interlibrary Lending and Document Delivery Network (GILLDDNET). Oxford: The International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications (INASP); 2004.

Alidousti, Sirous, Nazari, Maryam, Abooyee Ardakan, Mohammad. A Study of Success Factors of Resource Sharing in Iranian Academic Libraries. Library Management. 2008; 29(8/9):711–728.

Appleyard, Andy. British Library Document Supply – A Fork in the Road. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):12–16.

Aqili, Seyed Vahid, Moghaddam, Alireza Isfandyari. Bridging the Digital Divide. The Role of Librarians and Information Professionals in the Third Millennium. The Electronic Library. 2008; 26(2):228–237.

Atkins, David P. Going Global: Examining Issues and Seeking Collaboration for International Interlending, the View from the US. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(2):72–75.

Baich, Tina, Zou, Tim Jiping, Weltin, Heather, Yang, Zheng Ye. Lending and Borrowing across Borders. Issues and Challenges with International Resource Sharing. Reference & User Services Quarterly. 2009; 49:54–63.

Baker, Kim, Bridging the Digital Divide: Working toward Equity of Access through Document Supply Services in South Africa. Presented at the 8th Interlending and Document Supply International Conference, 28–31 October, 2003. [Canberra, Australia].

Bensoussan, Babette E., Fleisher, Craig S. Analysis without Paralysis: 10 Tools to Make Better Strategic Decisions. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: FT Press; 2008.

Bhatti, Rubina. British Library Document Supply Centre (DSC): A Case Study. Opportunities for Pakistani Academics and Researchers. Pakistan Library & Information Science Journal. March 2008; 39(1):11–20.

Bonamici, Andrew, Huter, Steven G., Smith, Dale. Cultivating Global Cyberinfrastructure for Sharing Digital Resources. EDUCASE Review. March/April 2010; 45(2):10–11.

Bonk, Sharon. Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery in the United Kingdom. RQ. Winter 1990; 30(2):230–240.

Brink, Helle, Andresen, Leif. Danish Libraries in WorldCat – and Ordering Facilities to Ten Danish Libraries. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(3):147–151.

Britz, Johannes, Lor, Peter J. A Moral Reflection on the Information from South to North: An African Perspective. Libri. 2003; 53:160–173.

Butler, Barbara, Webster, Janet, Watkins, Steven G., Markham, James W. Resource Sharing within an International Library Network: Using Technology and Professional Cooperation to Bridge the Waters. IFLA Journal. 2006; 32(3):189–199.

Chapman, Robert J. Simple Tools for Enterprise Risk Management. Chicester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2006.

Chelak, Afshin M., Azadeh, Fereydoon. The Development of the Union Catalogues in Iran: The Need for a Web Based Catalogue. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(2):118–125.

Chellapandi, Sharmini, Wun Han, Chow, Chiew Boon, Tay. The National Library of Singapore Experience: Harnessing Technology to Deliver Content and Broaden Access. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):40–48.

Chudnov, Daniel, The History of Interlibrary Loan. 2001. available at. http://old.onebiglibrary.net/mit/web.mit.edu/dchud/www/p2p-talk-slides/img0.html

Cimen, Ertugrul, Tuglu, Ayhan, Manyas, Mehmet, Çelikba![]() , Sema, Çelikba

, Sema, Çelikba![]() , Zeki. KITS: A National System for Document Supply in Turkey. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):58–66.

, Zeki. KITS: A National System for Document Supply in Turkey. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):58–66.

Clavel-Merrin, Genevieve. Many Roads to Information: Digital Resource Sharing and Access at the Swiss National Library. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):54–57.

Colinmaire, Hervé. Science and Technology at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France: A New Policy, a New Electronic Library and a New Access to Information. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):22–25.

Condill, Kit, Rudasill, Lynne. GIVES: Interlending and Discovery for non-English Resources. Interlending & Document Supply. 2009; 37:49–60.

Cornish, Graham P., The Book Stops Here: Barriers to International Lending and Document Supply. presented at the 5th Interlending and Document Supply International Conference. held in Aarhus, Denmark, 24–28 August 1997.

Cornish, Graham P. Brief Communication: Document Supply in Latin America – Report of a Seminar. Interlending & Document Supply. 2001; 29:126–128.

Cornish, Graham P., Prosekova, Svetlana. Document Supply and Access in Times of Turmoil: Recent Problems in Russia and Eastern Europe. Interlending & Document Supply. 1996; 24(1):5–11.

Datta, Ansu, Baffour-Awuah, Margaret. Botswana and the Southern African Interlibrary Lending System: Cooperation or Dependency? Information Development. January 1991; 7(1):25–31.

Dekkers, M., The Establishment of a Union Catalogue in Greece: Standards and Technical Issues. 1997. available at: www.ntua.gr/library/deliv01_p2.htm

Dulle, Frankwell W., Minishi-Majanja, M.K. Fostering Open Access Publishing in Tanzanian Public Universities: Policy Makers’ Perspectives. Agricultural Information Worldwide. 2009; 2(3):129–236.

Durrani, Shiraz. Information and Liberation. Writings on the Politics of Information and Librarianship. Duluth, MN: Library Juice Press; 2008.

Elkington, Nancy E., Massie, Dennis. The Changing Nature of International Resource Sharing: Risks and Benefits of Collaboration. Interlending & Document Supply. 1999; 27(4):148–153.

Erdogan, Phyllis, Karasözen, Bulent. International Perspectives: Portrait of a Consortium: ANKOS (Anatolian University Libraries Cornsortium). The Journal of Academic Librarianship. July 2009; 35(4):377–385.

Erickson, Carol A. ABLE in Afghanistan. American Libraries. January/February 2010; 44–47.

Erokina, Nadezhda. The Russian State Library: Russia’s National Centre for Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):37–39.

Fahmy, Engy I., Rifaat, Nermine M. Middle East Information Literacy Awareness and Indigenous Arabic Content Challenges. The International Information & Library Review. 2010; 42:111–123.

Gauslå, Arne. The Norwegian “Bibliotek” Database in a Nordic ILDS Perspective. Interlending & Document Supply. 2006; 34(2):57–59.

Gillet, Jacqueline. Sharing Resources, Networking and Document Delivery: The INIST Experience. Interlending & Document Supply. 2008; 36(4):196–202.

Haire, Muriel. A National Document Supply Co-Operative among Healthcare Libraries in Ireland. Journal of the European Association for Health Information and Libraries. 2009; 5(3):6–10.

Hanington, Debbie, Reid, David. Now We’re Getting Somewhere – Adventures in Trans Tasman Lending. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(2):76–81.

Igwe, Kingsley Nwadiuto. Resource Sharing in the ICT Era: The Case of Nigerian University Libraries. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Information Supply. 2010; 20(3):173–187.

Iraq National Library Rebuilds Amid Continued Violence, Iraq National Library Rebuilds Amid Continued Violence. American Libraries, November/December 2010:20.

Jia, Ping. The Development of Document Supply Services in China. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(3):152–157.

Kaul, S. DELNET – The Functional Resource Sharing Library Network: A Success Story from India. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(2):93–101.

Kearns, Kevin P. From Comparative Advantage to Damage Control: Clarifying Strategic Issues Using SWOT Analysis. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. 1992; 3(1):3–22.

Kefford, Brian International Interlibrary Lending: A Review of the LiteratureBoston Spa: International Federal of Library Associations and Institutions. International Office for International Lending, 1982.

Kelsall, Paula, Onyszko, Elizabeth. Interlibrary Loan Services at Library and Archives Canada. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):17–21.

Keniston, Kenneth, Kumar, Deepak. IT Experience in India: Bridging the Digital Divide. New Delhi: SAGE Publications; 2004.

Kingma, R., Mouravieva, Natalia. The Economics of Access versus Ownership: The Library for Natural Science. Russian Academy of Sciences. Interlending & Document Supply. 2000; 28(1):20–26.

Kniffel, Leonard. One Man’s Vision for the Future: Books for the Children of Ethiopia. American Libraries. October, 2010; 41:22–23.

Kyle, Barbara. Privilege and Public Provision in the Intellectual Welfare State. Journal of Documentation. 2005; 61(4):463–470.

Massie, Dennis. The International Sharing of Returnable Library Materials. Interlending and Document Supply. 2000; 28(3):112.

McCaslin, David. What are the Expectations of Interlibrary Loan and Electronic Reserves during an Economic Crisis? Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve. September 2010; 20(4):227–231.

McGrath, Mike. Interlending and Document Supply: A Review of the Recent Literature: 71. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(3):168–174.

Mocnik, Vida. Interlending Among the States of Former Yugoslavia. Interlending & Document Supply. 2001; 29(3):100–107.

Moreno, Margarita, Xu, A. The National Library of Australia’s Document Supply Service: A Brief Overview. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):4–11.

Morris, Leslie R. How Libraries Outside North America Can Increase Their Lending to the U.S. and Canada. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Information Supply. 2002; 12(4):1–2.

Nixon, Donna. An Evaluation of How Copyright, Licensing Agreements & Contract Law are Interacting to Restrict Academic Library Interlibrary Loan Abilities. University of North Carolina; 2001. [Master’s thesis].

Omekwu, C. Current Issues in Access Documents in Developing Countries. Interlending and Document Supply. 2003; 31:130–137.

Pakistan Flood Recovery Agonizing, Pakistan Flood Recovery Agonizing. American Libraries, November/December 2010:23.

Petrusenko, T.V., T.M. Zharova and L.D. Startseva. ‘Ill Service at National Library of Russia: Capabilities Prompted by New Technologies’. In Libraries and Associations in the Changing World: New Technologies and New Forms of Collaboration: Conference Proceedings. The Anniversary International Conference Crimea 98, Sudak, Ukraine, pp. 560 (in Russian with English abstract).

Rosemann, Uwe, Brammer, Markus. Development of Document Delivery by Libraries in Germany Since 2003. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):26–30.

Sahoo, Bibhuti Bhusan. Need for a National Resource Sharing Network in India: Proposed Model. In: Paper presented at the Workshop on Information Resource Management. Bangalore, India: DRTC; 13–15 March, 2002.

Schöpfel, J. Interlibrary Loan and Document Supply in France: The Montpellier Meeting. Interlending & Document Supply. 2005; 33(1):56–58.

Seal, Robert A. Interlibrary Loan: Integral Component of Global Resource Sharing. Resource Sharing & Information Networks. 2002; 16(2):227–238.

Soares, Elisa Maria Gaudencio. Document Supply and Resource Sharing in Portuguese Libraries: The Role of the National Library. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(1):31–36.

Spies, Phyllis B. Key Barriers to International Resource Sharing and OCLC Actions to Help Remove Them. Interlending & Document Supply. 2001; 29:169–174.

Taha, Ahmed. A New Paradigm for Networked Resource Sharing in the United Arab Emirates Universities. Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve. 2010; 20(5):293–301.

Taitt, Glenroy. Co-Operation among Caribbean Theological Libraries: A Case Study. Libri. 2005; 55:148–153.

Toplu, Mehmet. Progress in Document Delivery Services and Turkey Perspective. Turkish Librarianship. 2009; 23(1):83–118. [(in Turkish with English summaries)].

Van Borm, J. To Russia with Love: A European Union Project in St. Petersburg for Library Cooperation in General, ILDS in Particular. Interlending & Document Supply. 2004; 32(3):159–163.

Wanner, Gail, Beaubien, Anne, Jeske, Michelle. The Rethinking of Resource-Sharing Initiative: A New Development in the USA. Interlending & Document Supply. 2007; 35(2):92–98.

Wu, Ming-der, Huang, Yu-tin, Lin, Chia-yin, Chen, Shih-chuan. An Evaluation of Book Availability in Taiwan University Libraries: A Resource Sharing Perspective. Library Collections, Acquisitions, & Technical Services. 2010; 34:97–104.

Yoo, Suhyeon. Document Delivery through Domestic and International Collaboration: The KISTI Practice. Interlending & Document Supply. 2010; 38(3):175–182.

Zou, Tim Jiping, Xiaofen Dong, Elaine, In Search of a New Model: Library Resource Sharing in China – a Comparative Study. Presented at the World Library and Information Congress: 73rd IFLA General Conference and Council, 19–23 August 2007. [Durban, South Africa].