Case studies in global resource sharing

Abstract:

In this chapter, the results of an email survey conducted by the authors in late 2010 are discussed. The survey was designed to gather information about participation in international interlibrary lending and to learn about the greatest barriers to successful global resource sharing activities.

Introduction

Despite decades spent building technological infrastructure and work processes to handle international requests for library materials, the question of why some requests for foreign materials succeed while others fail remains a complex one. To better understand this complexity, it’s important to identify some of the key issues that exist.

Frequently a topic of discussion in both the professional literature and conference proceedings of the library and information management discipline, several studies done in the past 10 years demonstrate the range of practical and philosophical concerns libraries have had in the past and continue to have surrounding the subject of global resource sharing.

In 1998, the Research Libraries Group (RLG) surveyed international libraries in the RLG SHARES group and found that although there was demand for international interlibrary loan, the actual number of transactions was relatively low. The study also noted the chief impediments to sharing from the perspective of both U.S. and non-U.S. libraries, and the low associated fill rates, including a combination of complicated and time-consuming procedures, high costs of shipment, and the potential for loss or damage related to travel time and distance (Elkington and Massie, 1999).

The situation was not much better in 2002 when Robert Seal, now Dean of Libraries at Loyola University Chicago, summarized the top ten barriers to global resource sharing:

2. Insufficient funding to start or sustain cooperative sharing.

3. Outdated or non-existent infrastructure for technology, systems and telecommunications.

4. Lack of international standards for bibliographic description, record format, and data exchange.

6. Insufficient holdings or location information.

7. Lack of knowledge about operations, practices, and policies in other countries.

8. Negative or suspicious attitudes.

9. Lack of history or tradition of international cooperation.

More recently, the International Interlibrary Loan Committee of the American Library Association section on Sharing and Transforming Access to Resources (STARS) conducted a survey of libraries in the U.S. to look at the current state of international interlibrary loan. In 2007, when this survey was performed, the environment was more favorable. At that time, 94 percent of all respondents borrowed and lent returnables and non-returnables internationally. Several factors were also identified that limited ILL to and from non-U.S. libraries, including high international shipping costs, lengthy delivery times, OCLC supplier status and communication and technology differences.

Other issues identified in the STARS study included those surrounding bibliographic discovery and citation verification along with methods for payment, shipment and delivery. In conclusion, the authors point out:

Many of the same barriers to international ILL exist today that existed ten years ago. Although advances have been made in citation verification thanks to the growth of the Internet, problems still exist because of decentralized catalogs and language barriers. International ILL is plagued by issues surrounding technology and communications. Cost remains an impediment to the global sharing of resources, especially in the area of returnable items where shipping also plays a role. (Baich et al., 2009, 62)

While libraries in the U.S. have a good understanding of how their own processes and practices work in relation to international ILL, they have a more limited comprehension of ILL infrastructure and activity in other countries. As a result, in early 2010, we decided to gather information from non-U.S. libraries about international ILL. Like the 2007 STARS survey, we wanted to discover to what extent libraries participate in international ILL, what tools and technologies are used, what barriers are encountered and, finally, what the future of global resource sharing might look like.

Participation in global resource sharing – survey responses

To get at this information, a very brief, informal questionnaire was designed using SurveyMonkey, a web-based survey software tool (www.surveymonkey.com). A link to the survey, which contained seven general questions, was sent to the email addresses of 530 international contacts compiled by the authors. A total of 49 messages were returned as undeliverable. An email message with a link to the survey was also sent to DOCDEL-L, the IFLA document delivery and interlending mailing list with 419 current subscribers, as well as to ILL-L, a U.S. based discussion forum for anyone with a professional interest in interlibrary loan, document delivery and resource sharing that has 2109 subscribers. The survey was opened 232 times, with 175 completed surveys.

SurveyMonkey has some advantages for data gathering, including a respondent-friendly format, but it also has its limitations. Both the initial email message and the link to the survey, housed on a third party server, were blocked by institutions that maintain high network security and employ spam blockers. The initial email message and the survey itself were written in English, further restricting the potential number of responses. The results of the initial survey, are perhaps more descriptive than representative but did include some interesting findings.

Country representation

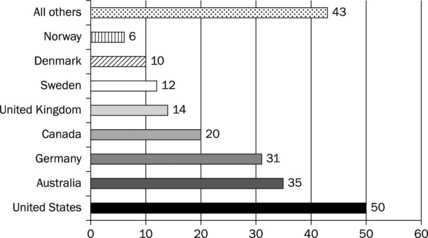

Question #1 asked respondents to identify their geographic location (Figure 5.1). There were 221 responses to this question.

Perhaps not surprisingly a number of responses (50) came from U.S. libraries; however, replies also came from 171 institutions located outside the United States. As might be suspected, English-speaking countries are the next largest category but with other countries in Europe also well represented. The 43 responses from 24 additional countries in the ‘All others’ category are shown in Table 5.1.

Library type

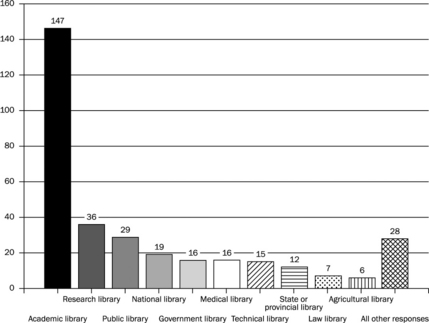

Respondents were then asked to identify what type of library was represented (Figure 5.2). Of the 221 responses to this question, the overwhelming majority of libraries (66.5 percent) represented were academic, but included a fairly good mix of other types. Although ‘Other’ was selected by 28 (16 percent) of the survey takers, there was no description as to what was meant.

Lending practices

The next two questions in the survey asked about current lending practices. In answer to the question: ‘Does your library receive requests from foreign libraries to borrow your materials?’ a slim majority of the 214 respondents (112 or 52.3 percent) answered ‘Yes, occasionally,’ while another 88 or 41.1 percent responded ‘Yes, frequently.’ Less than 6 percent of those taking the survey responded ‘No.’ In the comments section for this question, replies ranged from ‘Maybe once a year’ to more than 4,500 requests per year from a Canadian library. For most libraries, the answer is probably closest to this one received from another library in Canada: ‘More than occasionally but less than frequently.’

In answer to the second question about lending: ‘Does your library lend its own library materials outside national borders?’ there was a greater variety in responses and comments. The majority of the 211 respondents (148 or 70.1 percent) indicated their library lends both articles and books; 14 (6.6 percent) lend articles only while 10 (or 4.7 percent) lend books only. Twenty-one libraries (10 percent) responded ‘It depends on a number of factors,’ and 17 libraries (or 8.1 percent) replied they do not lend internationally. A comment from South Africa indicated books were not generally lent although copies of articles and theses are supplied to libraries internationally. A library in the United States lends items that can be scanned and sent via email only. Several responses suggested that whether a book might be lent or not was decided on a case-by-case basis. A respondent from New Caledonia wrote: ‘My library is an organisational library with branches in several countries. We frequently lend among the branches, but we also occasionally lend to other libraries in other countries.’ Several libraries will lend internationally to close geographic neighbors, such as between the United States and Canada, Australia and New Zealand or within Europe. Finally, some libraries will lend if payment is made with IFLA vouchers or for library use only.

A question about borrowing asked whether the library sent requests for materials to foreign libraries. Again, the majority (147 or 70 percent) of the 207 respondents answered that both books and articles were requested. Ten percent of the respondents indicated they would request non-returnables only while another 10 percent stated it would depend on a variety of different factors. Only 5 percent replied that they would not request internationally. Again, the responses showed the diversity in issues libraries face when borrowing internationally. One library in the U.S. indicated they would attempt to borrow only if the institution is listed as a ‘Library Very Interested in Sharing’ (LVIS) library because they do not want to send funds internationally. Other libraries would borrow only if payment could be made by IFLA voucher. Interestingly, a library in Canada commented: ‘ILL requests for books for which there are no North American locations are purchased if possible. Usually it is cheaper than paying the costs of international shipping and loan charges.’

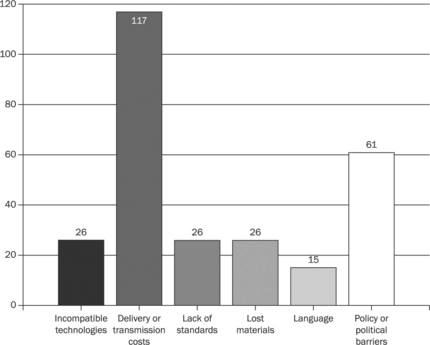

The final question in the informal survey asked respondents to give an opinion on the single greatest barrier to international sharing of library resources at this time (Figure 5.3).

For the 191 responses to this question, the majority of libraries (61.3 percent) found that delivery or transmission costs presented the biggest obstacle, with policy or political barriers the runner-up at nearly 32 percent. Incompatible technologies, lack of standards, and lost materials were found to be equally troublesome at 13.6 percent each. Finally, language was seen as an obstruction for 7.9 percent of the respondents. Survey takers were asked for additional comments in this section and 51 individual responses were received. Some of the replies simply confirmed the rating given for this question, while others provided more detail or added other categories. Three libraries, for example, specifically mentioned copyright as a problem for both borrowers and lenders. Several respondents indicated that it’s often difficult to make an initial contact with a potential lender:

Often finding contact information is very difficult even when you are on the library’s website. Sometimes language is the issue and it makes it difficult to navigate the site – sometimes it is just impossible to find it even with an English option. We often send the request by email and we do not always get a reply. – Canada

It is also sometimes hard to locate contact details and information on lending policies for libraries – Canada, Australia, Japan, Germany and NZ, all have a directory or database of libraries and their resource sharing policies which makes it much easier to make requests – it would be great if more countries did this. – New Zealand

Regularly we will request items from libraries that, rather than declining to supply, will just ignore correspondence. – United Kingdom

Locating the item and then having to deal with individual libraries rather than being able to request and pay through a central system. – Australia

Sometimes in bigger libraries difficult to know where to address the request: book is found from database but to whom to write – frustrating. – Finland

Problems with getting contact for the first time … Sometimes we get no answer to our requests. – Germany

Another set of comments dealt with the expense and length of time needed to negotiate a successful international ILL:

As a library on an island in the middle of the Pacific, delivery costs are always significant. – New Caledonia

Our budget is tight and postage is expensive from this distance. This limits book loans. Also costs for articles can be prohibitive even if the technology allows for it. – Australia

Libraries in the United States specifically cited problems with shipping and customs forms as significant barriers to international cooperation:

If we send books outside of the country, we have to deal with customs paperwork and higher shipping costs. I imagine that international libraries are reluctant to loan to us – because of the possibility of materials getting lost in the mail.

If I had to name a barrier, I would select the time it takes for material to be processed through customs.

There are certain customs forms to declare cost and to eliminate customs duty upon return of the item and it is not clear how to use them.

In another set of comments, survey respondents talked about attitudes regarding resource sharing in general being the greatest barrier:

Belief that it is going to be time consuming and expensive. There also seems to be an unnecessary worry that items are going to be lost in transit but in our experience this is no more often than with domestic deliveries. – United Kingdom

We need to address the fact that even our colleagues consider ILL expensive – work on attitudes by enlightenment. – Denmark

It is more of a perceived risk and a comfort level dealing with libraries within our borders. – United States

Countries show their collection in OCLC WorldCat, but are not willing to participate in resource sharing. – Denmark

The final question of this survey asked respondents to indicate interest in being contacted individually to discuss international resource sharing in more depth. A total of 67 responses were received and to this group a second questionnaire was sent. The responses to this final question form the basis for the selected studies that appear in the next chapter.

References

Baich, Tina, Jiping Zou, Tim, Weltin, Heather, Ye Yang, Zheng. Lending and Borrowing Across Borders: Issues and Challenges with International Resource Sharing. Reference & User Services Quarterly. 2009; 49(1):54–63.

Elkington, Nancy E., Massie, Dennis. The Changing Nature of International Resource Sharing: Risks and Benefits of Collaboration. Interlending & Document Supply. 1999; 27(4):148–153.

Seal, Robert A. nterlibrary Loan: Integral Component of Global Resource Sharing. Resource Sharing & Information Networks. 2002; 16(2):227–238.